The speed and scale of the COVID-19 pandemic has been overwhelming and continues to rapidly spread, with various clinical presentations, including neuropsychiatric symptoms.Reference Rogers, Chesney, Oliver, Pollak, McGuire and Fusar-Poli1 Whether SARS-CoV-2 is neurovirulent or whether indirect generalised systemic changes exist behind these neuropsychiatric symptoms is not yet established.Reference Hawkins, Sockalingam, Bonato, Rajaratnam, Ravindran and Gosse2,Reference Pajo, Espiritu, Apor and Jamora3 Recent studies have found structural changes to the brain, including various stages of gliosis, hypoxic changes, cerebral venous neutrophilic infiltrates and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates, in addition to variable degrees of neuronal cell loss and axonal degeneration and injury.Reference Hawkins, Sockalingam, Bonato, Rajaratnam, Ravindran and Gosse2

Data from observational studies on neuropsychiatric symptoms have recorded variability in the types and severity of the neurological and psychiatric manifestations of COVID-19.Reference Rogers, Chesney, Oliver, Pollak, McGuire and Fusar-Poli1 Although delirium was, expectedly, reported the most, other serious neuropsychiatric symptoms were reported too – namely, catatonia.Reference Caan, Lim and Howard4 Catatonia is well established as associated with serious physical complications, such as dehydration, respiratory aspiration, deep venous thrombosis or pulmonary emboli, and progression to malignant catatonia.Reference Clinebell, Azzam, Gopalan and Haskett5 Although untreated catatonia might have lethal outcomes, catatonia has a favourable treatment response. Catatonia is known to be underdiagnosed in non-psychiatric settings and is often misidentified as delirium, conversion disorder, psychosis or akinetic mutism, as many catatonic symptoms and signs are non-specific and are shared by various diagnostic possibilities.Reference Anand, Kumar Paliwal, Singh and Uniyal6 Subsequently, questioning the available evidence for the association between COVID-19 and catatonia is essential. Establishing a link between the two variables by analysing the available literature and data would raise important points and directions regarding treatment in patients with COVID-19. In this paper, we aim to identify the available findings regarding catatonia presentations in patients with COVID-19, and evaluate their connotations.

Method

This study aims to review the current available literature on catatonia presentations of patients with COVID-19. We did a focused literature search of PubMed, EMBASE, PsycINFO, BIN and CINAHL databases. We used the following search parameters for each database: ‘((covid 19).ti,ab OR (COVID-19).ti,ab OR (SARS-CoV-2).ti,ab) AND ((stupor).ti,ab OR (catalepsy).ti,ab OR (waxy flexibility).ti,ab OR (mutism).ti,ab OR (mute).ti,ab OR (negativism).ti,ab OR (posturing).ti,ab OR (mannerisms).ti,ab OR (stereotypies).ti,ab OR (psychomotor agitation).ti,ab OR (grimacing).ti,ab OR (echolalia).ti,ab OR (echopraxia).ti,ab OR (Command automatism).ti,ab OR (automatism).ti,ab OR (catatonia).ti,ab)’. The search spanned from the initial descriptions of COVID-19 to 16 January 2022. The search criteria was designed to include each individual symptom of catatonia, to detect grey literature and potential catatonia cases that did not meet the full diagnostic criteria for catatonia and which might fall under the diagnosis of unspecified catatonia. Unspecified catatonia is an independent category in the DSM-5, which applies to presentations in which symptoms characteristic of catatonia cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational or other important areas of functioning, but either the nature of the underlying mental disorder or other medical condition is unclear, full criteria for catatonia are not met or there is insufficient information to make a more specific diagnosis. The creation of this category is aimed to allow for the rapid diagnosis and specific treatment of catatonia in severely ill patients. Of note, in the DSM-IV, two out of five symptom clusters were required to diagnose catatonia if the context was a psychotic or mood disorder, whereas only one symptom cluster was needed if the context was a general medical condition.

We included any study (case report, case series and observational studies) written in English which explored and reported the presence of catatonia as a syndrome, or the co-occurrence of a minimum of two symptoms of catatonia, particularly the two core symptoms of stupor and mutism, in patients with COVID-19. Articles were excluded if they reported catatonic symptoms in the context of a secondary reaction to the psychological stresses associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, or because of the psychological implications of public lockdown. Animal studies and studies in languages other than English were also excluded. This review followed the PICO (population, intervention, control and outcomes) structure and technique to frame the search as a diagnostic problem. Level of evidence were rated according to the Oxford Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine (https://www.cebm.net/contact/), a UK-based service providing rapid evidence reviews and data analysis relating to the coronavirus pandemic, which is affiliated with Oxford University's Nuffield Department of Primary Care Health Sciences.

This paper did not collect data from patients or patients’ clinical notes, hence there was no need to obtain ethical approval.

Results

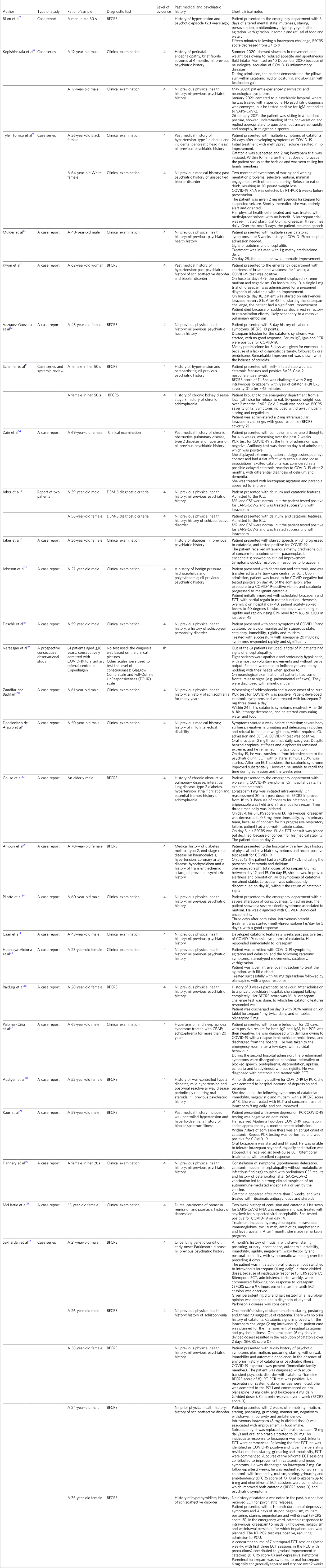

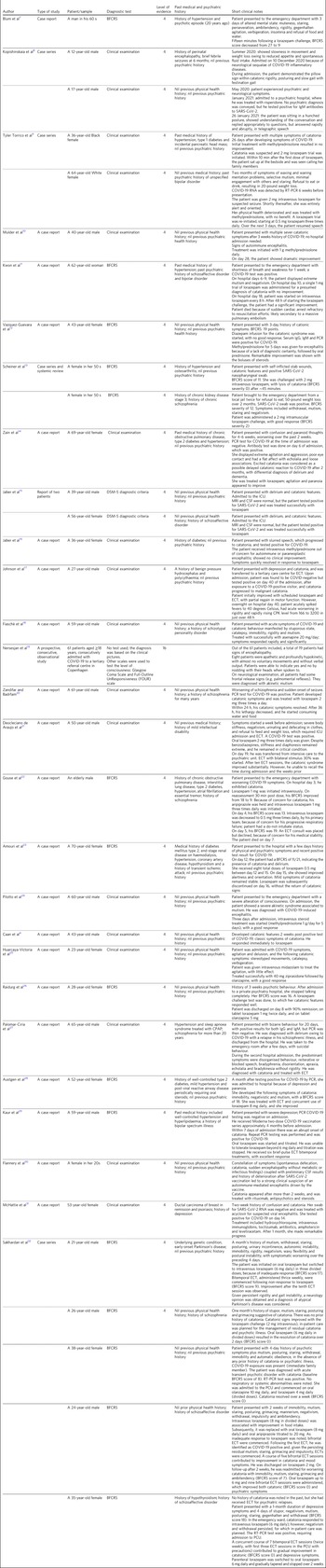

Between the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2019 and January 2022, we identified a total of 204 studies (71 [35%] from PubMed, 90 [44%] from EMBASE, 22 [11%] from PsycINFO, four [2%] from BIN and 17 [8%] from CINAHL). Considering the rarity of catatonia diagnoses, the total number of studies obtained was high. This finding is possibly a result of our search parameters, which included identifying and including studies that discussed the co-occurrence of individual symptoms that form the diagnostic criteria of catatonia. Of the 204 studies identified, 27 (13%) met our inclusion criteria. Table 1 summarises the 27 studies included in this review.

Table 1 Included publications and brief notes from their findings

BFCRS, Bush–Francis Catatonia Rating Scale; IgM, immunoglobulin M; RT-PCR, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; IgG, immunoglobulin G; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; ICU, intensive care unit; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; ECT, electroconvulsive therapy; CPK, creatine phosphokinase ; CPAP, continuous positive airway pressure; PCU, progressive care unit.

Application of the inclusion criteria was based on two stages of screening: first, the titles and the abstracts, followed by the full texts of those studies to identify description of catatonia. Twenty-five (12%) of 204 articles recorded a diagnosis of catatonia as a comorbidity to COVID-19, and all were either an individual case report or a series of case reports. One (<1%) study reported the diagnosis of akinetic mutism in eight patients, but they exhibited the two core symptoms of catatonia, and one (<1%) study reported catatonic features in a patient with encephalitis and delirium. Both studies were included as they recorded mutism and a hypokinetic state in their patients, indicating the possibility of unspecified catatonia.

The 27 included articles in this review observed a total of 42 patients, ranging from the ages of 12 to ≥70 years. Of those patients, 17 (40%) were female and 17 (40%) were male, with no demographic data available for eight (10%) patients. The largest cluster of patients were aged >50 years (17 [40%] out of 42 patients); among them, nine (53%) out of 17 patients were aged >60 years. With the increase in the prevalence of COVID-19 in individuals aged <18 years, reports concerning catatonia in COVID-19 in younger individuals have begun to appear. Two (5%) out of 42 patients identified in this review were aged <18 years. The Bush–Francis Catatonia Rating Scale was used as a diagnostic tool to identify catatonia in ten (24%) out of 42 patients, and 32 (76%) patients were identified depending on their clinical examination.

Age, previous history of certain physical health problems and previous psychiatric history are predisposing factors for catatonia in COVID-19. The psychiatric premorbid diagnoses reported in these cases included bipolar disorder in two (5%) patients, schizophrenia in five (12%) patients, schizoaffective disorder in four (10%) patients, schizotypal personality disorder in one (2%) patient, depression in one (2%) patient and mild intellectual disability in one (2%) patient. The most common physical premorbid diagnoses were hypertension, followed by diabetes, chronic kidney diseases, chronic lung diseases, ischaemic vascular diseases, neurological diseases and hypothyroidism, which were all reported separately or in combination. Ductal carcinoma of the breast in remission and psoriasis were also reported in one patient who presented with encephalitis and catatonia. No previous psychiatric or physical health problems were reported in ten (24%) out of 42 patients (Table 1).

Discussion

Taking in consideration the number of cases identified, the outcome of this review has presented catatonia as a possible complication of COVID-19, regardless of age, gender and the background of the physical or mental health status of patients. However, this review indicates that the strength of evidence for catatonia in COVID-19 was poor, as there are no robust observational studies available. The below discussion represents the 34 patients whose data were available. The presentation of catatonia in COVID-19 varied in onset, severity and duration. Catatonic states were reported throughout the acute and subacute phases of COVID-19, as well as a long-term post-encephalitis neuropsychiatric complication. Catatonia occurred in combination or independently of any other psychiatric symptoms. However, catatonia mainly arose concurrent with the acute phase of COVID-19, but was reported as a long-term complication for COVID-19 (Table 1).

Lorazepam was used in 22 patients, and demonstrated notable and even rapid improvements in the core symptoms of catatonia, including mutism, echolalia, rigidity, waxy flexibility and automatic obedience in 18 patients; the remaining four patients needed further electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).Reference Deocleciano de Araujo, Schlittler, Sguario, Tsukumo, Dalgalarrondo and Banzato21,Reference Kaur, Khavarian, Basith, Faruki and Mormando29,Reference Sakhardande, Pathak, Mahadevan, Muliyala, Moirangthem and Reddi32 Furthermore, lorazepam led to mild improvements in delirium in one patient,Reference Amouri, Andrews, Heckers, Ely and Wilson23 and improvement in agitation and paranoia in another.Reference Zain, Muthukanagaraj and Rahman14 Oral or intramuscular lorazepam challenge tests led to lysis of catatonia after 10–30 min in most cases. For example, a report from the Kern Medical Centre in California described two cases of suspected catatonia associated with COVID-19 who responded immediately to lorazepam injections, with marked improvement in their symptom profile.Reference Torrico, Kiong, D'Assumpcao, Aisueni, Jaber and Sabetian9 Delaying treatment with benzodiazepines because of worries about worsening delirium might be followed by serious physical complications, such as pulmonary embolism.Reference Kwon, Patel, Ramirez and McFarlane11 Steroid therapies were trialled in seven patients that were diagnosed with COVID-19-induced encephalopathy, which proved useful in four (57%) patients.Reference Torrico, Kiong, D'Assumpcao, Aisueni, Jaber and Sabetian9,Reference Mulder, Feresiadou, Fällmar, Frithiof, Virhammar and Rasmusson10,Reference Vazquez-Guevara, Badial-Ochoa, Caceres-Rajo and Rodriguez-Leyva12,Reference Jaber, Aisueni, Torrico, D'Assumpcao, Kiong and Sabetian16,Reference Pilotto, Odolini, Masciocchi, Comelli, Volonghi and Gazzina24,Reference Austgen, Meyers, Gordon and Livingston28 In the remaining three (43%) patients, steroid therapy failure was followed by successful lorazepam treatment.Reference Torrico, Kiong, D'Assumpcao, Aisueni, Jaber and Sabetian9,Reference Jaber, Aisueni, Torrico, D'Assumpcao, Kiong and Sabetian16,Reference Austgen, Meyers, Gordon and Livingston28 This finding suggests that the well-known efficacious responses to lorazepam therapy in catatonia is still valid in COVID-19, with almost a complete resolution of all catatonic signs in most cases. No serious unwanted side-effects were recorded. Although lorazepam is helpful in treating catatonia, lorazepam alone might not suffice. ECT should always have serious early consideration in catatonia, as it showed good results and safety even with the physical health complications of COVID-19.Reference Johnson, Kapoor and Kim17,Reference Deocleciano de Araujo, Schlittler, Sguario, Tsukumo, Dalgalarrondo and Banzato21,Reference Palomar-Ciria, Alonso-Álvarez, Vázquez-Beltrán and Blanco Del Valle27–Reference Kaur, Khavarian, Basith, Faruki and Mormando29,Reference Sakhardande, Pathak, Mahadevan, Muliyala, Moirangthem and Reddi32 In one patient, nonetheless, ECT was declined because of concerns regarding physical health problems.Reference Gouse, Spears and Nieves Archibald22 Despite the controversy surrounding antipsychotics in catatonia, two case reports described efficacious treatments utilising the antipsychotics olanzapine, asenapine and ziprasidone.Reference Vazquez-Guevara, Badial-Ochoa, Caceres-Rajo and Rodriguez-Leyva12,Reference Huarcaya-Victoria, Meneses-Saco and Luna-Cuadros25

In another aspect, COVID-19 has the potential to negatively affect the clinical course of established catatonia, as highlighted by the study by Johnson et alReference Johnson, Kapoor and Kim17 which described a 27-year-old male with a past medical history of normal pressure hydrocephalous and polycythaemia. He was first admitted for depression and increasing catatonic symptoms. He tested negative for COVID-19 on admission, but was infected during in-patient stay, and his catatonia deteriorated to malignant catatonia. The COVID-19 vaccinewas also reported as a possible cause for the catatonia presentation and it was treated with rituximab, an antipsychotic and steroids.Reference Flannery, Yang, Keyvani and Sakoulas30

Nersesjan et alReference Nersesjan, Amiri, Lebech, Roed, Mens and Russell19 enrolled 61 patients with COVID-19 who were admitted to Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen University Hospital, a tertiary referral centre in Denmark; the group identified encephalopathy in 19 patients, eight (42%) of whom were apathetic and severely hypokinetic or akinetic, with almost no voluntary movements and no verbal output. However, these eight patients were conscious and appeared aware of their surroundings through intelligible gaze responses. Those patients were given the diagnosis of akinetic mutism, and these symptoms lasted for a median of 4 days. These clinical observations could raise the possibility of unspecified catatonia. The Guidelines and Evidence-Based Medicine Subcommittee of the Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine states that the disorder fulfils DSM-5 criteria for ‘catatonic disorder due to another medical condition’, as all cases of akinetic mutism involve stupor, immobility and mutism,Reference Denysenko, Sica, Penders, Philbrick, Walker and Shaffer33 However, the guidelines recognise that this definition is complicated by the fact that some medical conditions can cause both akinetic mutism and catatonia.Reference Denysenko, Sica, Penders, Philbrick, Walker and Shaffer33

Additionally, Pilotto et alReference Pilotto, Odolini, Masciocchi, Comelli, Volonghi and Gazzina24 described a case of a 60-year-old patient with severe acute respiratory syndrome owing to COVID-19, who had only mild respiratory abnormalities and developed an akinetic mutism with abulia. He was considered as suffering from encephalitis and delirium secondary to COVID-19; however, this case report's clinical description fulfilled at least two of the diagnostic criteria of catatonia. Additionally, 3 days after admission, given the persistence of clinical symptoms, high-dose intravenous steroid treatment was started (methylprednisolone 1 g per day for 5 days) and was effective. In an exploratory study, Grover et alReference Grover, Ghosh and Ghormode34 systematically demonstrated that 30.2% of patients with delirium, regardless of aetiology, met the criteria for catatonia by scoring positive on two of the first 14 items of the Bush–Francis Catatonia Rating Scale. These findings suggest that catatonia can coexist with delirium.Reference Denysenko, Sica, Penders, Philbrick, Walker and Shaffer33,Reference Grover, Ghosh and Ghormode34 Following Grover et al's report, several successive case reports were published describing encephalitis and delirium with catatonia in the context of COVID-19 infection.Reference Mulder, Feresiadou, Fällmar, Frithiof, Virhammar and Rasmusson10,Reference Vazquez-Guevara, Badial-Ochoa, Caceres-Rajo and Rodriguez-Leyva12,Reference Jaber, Soliman, Campo and Mader15,Reference Kaur, Khavarian, Basith, Faruki and Mormando29 Lorazepam challenge test is widely used to either confirm or exclude catatonia.Reference Muliyala, Reddi and Bhaskaran35 In such ambiguous presentations, a challenge test with lorazepam would be beneficial.

Catatonia shares symptoms with a wide spectrum of physical and mental illnesses, such as status epilepticus, akinetic mutism, delirium, metabolic conditions (e.g. diabetic ketoacidosis), neuroleptic malignant syndrome, Parkinson's disease, extrapyramidal side-effects, substance misuse disorders, depressive disorders and psychosis. These examples are common illnesses that could be part of the aetiology for the progression and presentation of catatonia.Reference Wilcox and Reid36 Many of these conditions were described in patients with COVID-19 identified in our review.Reference Taquet, Geddes, Husain, Luciano and Harrison37–Reference Smith, Gilbert and Riordan40 Consequently, misclassification or missed diagnoses of catatonia is a possibility, and many cases fall within the grey zones of disease classification. Grey zones in medicine represent a complex situation and a great challenge to the diagnostic classification and subsequent treatment of patients.Reference Naylor41

In conclusion, our review was limited by the paucity of cohort studies and case–control studies designed to evaluate the epidemiology of catatonia and its course in COVID-19. The diagnostic problem was explored mainly through case reports, and the majority did not use a diagnostic rating scale. The diagnostic uncertainty extends to the cohort study included in this review that reported akinetic mutism in patients with COVID-19, which did not use diagnostic methods to examine the differential diagnosis and determine a precise and exclusive diagnosis.

Nevertheless, according to the reports available, evaluation of the possibility of catatonia in patients with COVID-19 infection and those presenting with mutism and hypokinesia or other symptoms of catatonia is important. As the pandemic continues, increasing the awareness of the diagnosis of catatonia among medical staff who are working with patients with COVID-19 would facilitate a timely identification and management of catatonia, which will have significant and lifesaving outcomes on the acute treatment of these cases.

Most patients with catatonia responded substantially and rapidly to benzodiazepines. The role of antipsychotic agents in treatment is controversial. ECT was effective, but would present a challenging circumstance in the prevention and treatment of medical complications of COVID-19.

About the authors

Abdallah Samr Dawood is a medical student at the Department of Medicine, GKT School of Medical Education, King's College London, UK. Ayia Dawood is a STEP pharmacist with the Pharmacy department at University Hospital Lewisham, Lewisham and Greenwich NHS Trust, UK. Samr Dawood is a consultant psychiatrist with the Department of Medical Education, Oxleas NHS Foundation Trust, UK.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, S.D., upon reasonable request. The searching protocol used in this review is available within the study.

Acknowledgements

We thank Paul K. Tang and Waad Attafi, both medical students at GKT School of Medical Education, for editing and reviewing the manuscript.

Author contributions

A.S.D., A.D. and S.D. contributed to the design and implementation of the research, to the analysis of the results and to the writing of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.