Joseph Wolpe was born on 20 April 1915, in Johannesburg, South Africa. He studied at the University of Witwatersrand (Johannesburg), where he obtained Bachelor of Medicine and Bachelor of Chemistry degrees, followed in 1948 by a post-graduate Doctor of Medicine degree. During military service in the Second World War, Captain Wolpe practised psychodynamic therapy but ended up greatly disappointed by the poor therapeutic outcomes attained. It was at this time that he took a dramatic shift from Freudianism to Pavlov's and Hull's conditioning-based approaches to behaviour modification. From 1948 to 1956, in parallel with his private psychiatric practice and part-time teaching in the Department of Psychiatry of the University of Witwatersrand, Wolpe perfected ‘systematic desensitisation’ as a new and effective method for treating anxiety disorders. Strongly inspired by the work of Mary Cover Jones (whom he reportedly dubbed ‘the mother of behaviour therapy’) on overcoming children's fears by means of desensitisation, Wolpe's systematic desensitisation consisted of repeated, progressive exposure to fear stimuli (graded in a hierarchical order, starting with the least disturbing stimulus) during induced relaxation. His widely recognised publications on experimental neuroses in laboratory animals and on desensitisation granted him an invitation to take a Fellowship at the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University from 1956 to 1957. During his stay in Stanford, Wolpe became acquainted with Karl Popper and eagerly incorporated critical rationalism in the philosophy of his own work, as reflected in his major book Psychotherapy by Reciprocal Inhibition (1958), described as ‘certainly one of the most significant books in the history of behavior therapy and, indeed, one of the most influential books in the history of clinical psychology’ (Rachman Reference Rachman2000).

In later life Wolpe earned many professional accolades: in 1979 he received the American Psychological Association's Distinguished Scientific Award for the Applications of Psychology; the University of Witwatersrand awarded him an honorary Doctor of Science degree in 1986, and the Association for Advancement of Behavior Therapy awarded him the Lifetime Achievement Award in 1995; from 1989 to 1997 (the year of his death), he was a Distinguished Professor at Pepperdine University in California. Wolpe was an indisputable pioneer of behavioural therapy and a visionary of the empirical approach to psychopathology and psychotherapy.

Psychotherapy by Reciprocal Inhibition (1958): a selected overview

The book, elegantly written in plain academic style, is divided in two sections: the first, ‘Background’, addresses the definition of neurotic behaviour, the rationale for reciprocal inhibition as a therapeutic principle and the aetiology of human neuroses; the second, ‘Psychotherapy’, describes the therapeutic applications of systematic desensitisation and evaluates the effectiveness of reciprocal inhibition methods.

‘Background’: neurotic behaviour as a result of learning

Throughout the book, Wolpe's meticulous attention to terminological accuracy is obvious. In the opening of the first chapter, he asserts as a fundamental assumption that human behaviour conforms to causal laws just as other phenomena do. He then introduces some core concepts, including: ‘response/reaction’ (i.e. a behavioural event that is perceived to be consequent to some antecedent event); ‘habit’ (i.e. a recurrent manner of responding to a given stimulus); and ‘behavioural patterns’ (i.e. generalised habits that mould individual responses in defined ways across different contexts). Remarkably, the last concept remains central in contemporary cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT), which generally aims at changing the patients’ maladaptive behavioural patterns to produce greater psychological flexibility and well-being (Sperry Reference Sperry2020). In other words, as reflected in Wolpe's concept of reciprocal inhibition, maladaptive habits are eliminated by enabling adaptive habits to develop in the same situation; thus reciprocal inhibition is concerned with the weakening of old responses by new ones.

Accordingly, ‘neurotic behaviour’ is defined as ‘any persistent habit of unadaptive behaviour acquired by learning in a physiologically normal organism’ (Wolpe Reference Wolpe1958: p. 32). For Wolpe, apart from clinical conditions based on abnormal organic states (e.g. schizophrenia) and some cases of hysteria, anxiety should be regarded as the cornerstone of all neuroses (e.g. depressive states, sexual dysfunction and panic) and several physical conditions (e.g. peptic ulcers, functional dermatoses and reactive asthma). In fact, during the 1980s, Wolpe (Reference Wolpe1986) would perfect his description of neurotic depression as a consequence of severe anxiety, anxiety-based interpersonal inadequacy or persistent reaction to bereavement. Even if the links between anxiety and depression are assumed to be bidirectional, there is now strong evidence for the unique effects of anxiety on the long-term course of depressive disorders (Coryell Reference Coryell, Fiedorowicz and Solomon2012; Kravitz Reference Kravitz, Schott and Joffe2014). Likewise, over half a century after the publication of Psychotherapy by Reciprocal Inhibition, the role of anxiety disorders as precursors to general medical conditions is well-documented and stands as one of the most promising research avenues in health science (Scott Reference Scott, Lim and Al-Hamzawi2016).

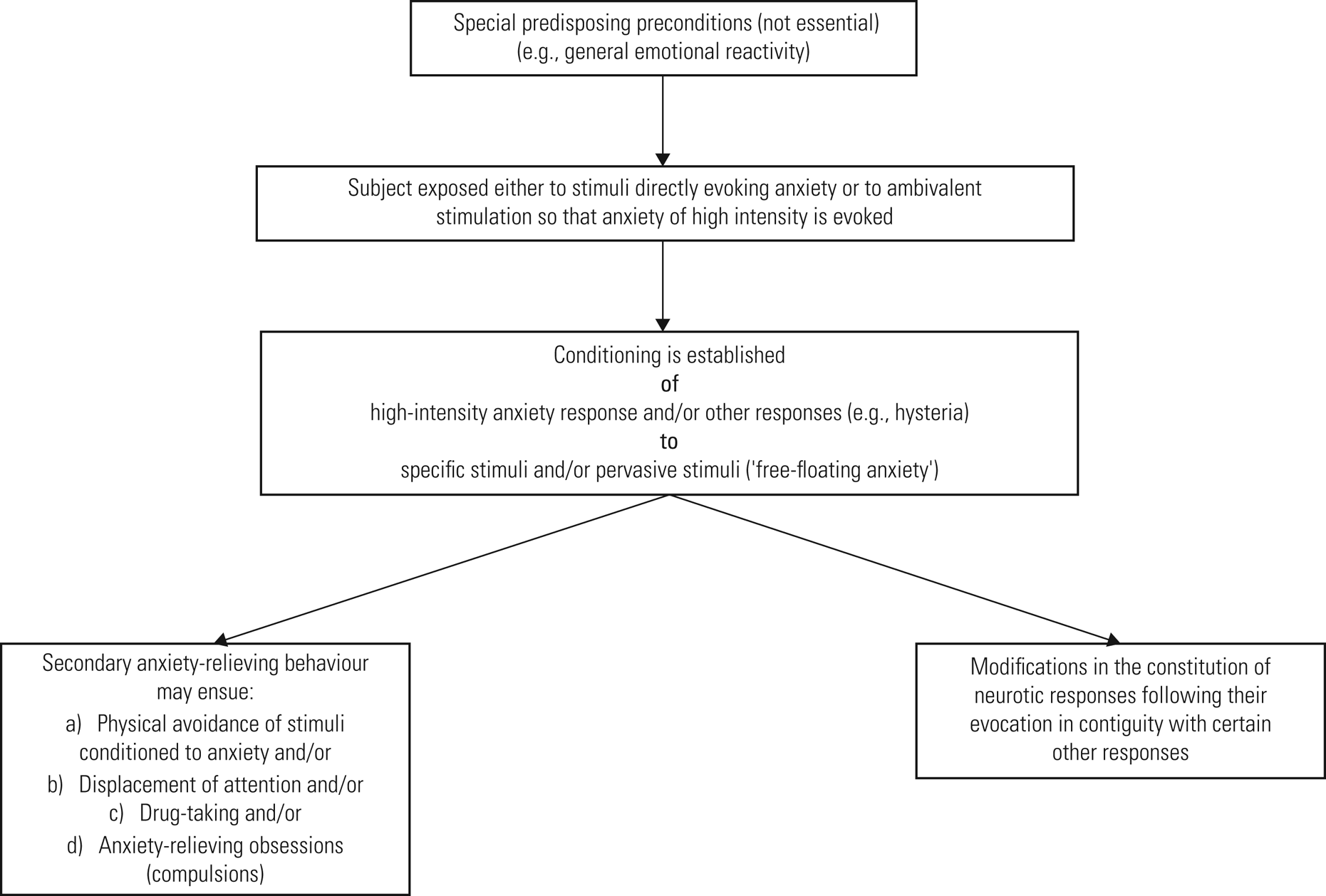

Challenging the common belief of most investigators back then, Wolpe asserted that ‘neurotic behaviour is the result not of damage but of learning’ (Wolpe Reference Wolpe1958: p. 37). After reviewing his laboratory work in the production of experimental neuroses, and just before outlining a comprehensive model for the aetiology of human neuroses (Fig. 1), Wolpe defines reciprocal inhibition as follows:

‘if a response antagonistic to anxiety can be made to occur in the presence of anxiety-evoking stimuli so that it is accompanied by a complete or partial suppression of the anxiety responses, the bond between these stimuli and the anxiety responses will be weakened’ (p. 71).

FIG 1 Summary of the aetiology of human neuroses (adapted from Wolpe Reference Wolpe1958).

In selecting responses to oppose the anxiety responses in clinical therapy (i.e. assertive responses, sexual responses and relaxation responses), Wolpe was guided by the assumption that responses largely involving the parasympathetic division of the autonomic nervous system would be presumably incompatible with the primarily sympathetic responses of anxiety. It is noteworthy that Wolpe's approach very much resembled the contemporary polyvagal perspective on emotion regulation processes in seeking the identification of neural circuits that downregulate threat reaction and functionally neutralise maladaptive defensive strategies (Porges Reference Porges2022).

‘Psychotherapy’: reciprocal inhibition put into clinical practice

The second part of the book, ‘Psychotherapy’, thoroughly outlines the clinical application of systematic desensitisation. As regards the quality of the therapeutic relationship, Wolpe's approach may be described as sensitive, encouraging and non-judgemental:

‘All that the patient says is accepted without question or criticism. He is given the feeling that the therapist is unreservedly on his side. This happens not because the therapist is expressly trying to appear sympathetic, but as the natural outcome of a completely nonmoralizing objective approach to the behaviour of human organisms. [ … ] In so far as this kind of expression of an attitude by the therapist can free the patient from some unadaptive anxieties, it must be regarded as psychotherapeutic’ (Wolpe Reference Wolpe1958: p. 106).

Consistently, contemporary CBT-based interventions evolved to strengthen the emphasis placed on a de-shaming style of therapeutic relationship (e.g. Gilbert Reference Gilbert and Simos2022).

Wolpe's interview procedure addressed three main components, which continue to be present in contemporary CBT case formulations (e.g. Kuyken Reference Kuyken, Padesky and Dudley2008): (a) identification of precipitating events; (b) identification of factors that appear to aggravate or ameliorate the symptoms; and (c) the patient's life history. At the end of the final anamnestic interview, the patient completes a self-sufficiency questionnaire, to estimate the probable duration of therapy, and a test for neuroticism, which is used to monitor therapeutic progress. Surprisingly, after some decades of being disregarded as an old-fashioned construct in psychopathology, neuroticism has recently re-emerged as a core dimension in the understanding and transdiagnostic CBT of emotional disorders (Barlow Reference Barlow, Curreri and Woodard2021).

The essence of all procedures based on reciprocal inhibition is opposing anxiety with emotional states incompatible with it. In his seminal work, Wolpe outlined the following responses antagonistic to anxiety: (a) assertiveness (often trained in therapy through role-play); (b) sexual arousal; (c) relaxation (i.e. training in progressive muscle relaxation, using the method developed by Jacobson in Reference Jacobson1929); (d) respiratory responses; (e) competitively conditioned motor responses (e.g. motor activity in the form or work or play); (f) pleasant responses in the life situation (e.g. ‘A particularly favourable succession of experiences may entirely eliminate given neurotic sensitivities’; Wolpe Reference Wolpe1958: p. 198); and (g) interview-induced emotional responses (e.g. the therapist's sympathetic acceptance of the patient's stance may induce reciprocal inhibition of anxiety).

Although not mutually exclusive, Wolpe further suggested that assertiveness responses could be specifically used for interpersonal anxieties; sexual responses for sexual anxieties (e.g. ‘such a patient is instructed to expose himself only to sexual situations in which pleasurable feelings are felt exclusively or very predominantly [ … ] to “let himself go” as freely as the circumstances allow’; Wolpe Reference Wolpe1958: pp. 130–1); relaxation responses for specific anxieties (e.g. phobias); and respiratory responses for pervasive (‘free-floating’, i.e. generalised) anxiety. Systematic desensitisation, as developed by Wolpe, starts with the construction of an anxiety hierarchy (Box 1) containing a list of stimuli to which the patient reacts with graded degrees of anxiety (the most disturbing item is placed at the top, and the least disturbing at the bottom of the list). This graded exposure therapy was mostly conducted using mental imagery and some antagonistic response to create counter-conditioning.

BOX 1 Example of an anxiety hierarchy of stimuli for a person with ‘free-floating’ (generalised) anxiety

The most disturbing item is at the top of the list.

(1) Seeing anybody whose behaviour suggests insanity

(2) The word ‘insanity’

(3) Seeing anyone with a gross deformity

(4) Seeing a person having an epileptic seizure

(5) Blood, especially if it comes from a hand (the more blood, the more disturbing)

(6) A person lying sick in bed (the sicker, the more disturbing)

(7) Entering a hospital

(8) The sight of physical violence

(9) Overhearing a quarrel

(10) The sound of weeping

(11) The sound of screaming

(12) Symptoms of illness in the patient himself

(13) The word ‘fear’

The efficacy of psychotherapy by reciprocal inhibition

The last chapter of the book is dedicated to evaluation of the effectiveness of reciprocal inhibition methods according to five criteria: symptomatic improvement; increased productivity at work; improved adjustment and pleasure in sex; improved interpersonal relationships; and ability to deal with ordinary psychological conflicts and reasonable daily stresses. As one of the first behavioural therapists, Wolpe asserted that ‘the only criterion that is an absolute “sine qua non” is symptomatic improvement’, and to this he added this witty footnote: ‘It is odd that those who pour scorn on “mere” symptomatic change on the supposition that “real” change requires something “deeper” so often fail to achieve even symptomatic change’ (Wolpe Reference Wolpe1958: p. 205). Based on his own case series of 210 patients with various diagnoses (i.e. anxiety states, hysteria, reactive depression, obsessions and compulsions, neurasthenia and mixed/unclassified), Wolpe reported that nearly 90% were classified as being ‘apparently cured’ or ‘much improved’ by the end of therapy, compared with the 50% success rate that was commonly reported for traditional counselling or psychoanalysis.

The legacy for cognitive–behavioural therapy

Exposure-based techniques – such as Wolpe's systematic desensitisation – remain at the core of the behavioural component of CBT, with demonstrated efficacy in a wide range of anxiety-mediated disorders (Rachman Reference Rachman2000; Craske Reference Craske, Treanor and Zbozinek2022). In fact, contemporary CBT-based models, such as acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), emphasise that behavioural change can be promoted by systematically engaging with previously avoided negative psychological content (e.g. emotions, thoughts, memories or bodily sensations) and disengaging from attempts to alter the form, frequency or situations that elicit these experiences (Gloster Reference Gloster, Hummel, Lyudmirskaya, Neudeck and Wittchen2012).

When studying Wolpe's masterpiece Psychotherapy by Reciprocal Inhibition, the reader immediately realises how much the current practice of CBT may benefit from revisiting the classic axioms of behavioural therapy. Wolpe was in many ways a visionary in the development of scientific psychotherapy, as can still be seen in the essential role of mental imagery in various CBT methods and techniques (Saulsman Reference Saulsman, Ji and McEvoy2019), in the continuing therapeutic applications of assertiveness training (Speed Reference Speed, Goldstein and Goldfried2018), in the utilisation of soothing rhythmic breathing to improve affect regulation (Steffen Reference Steffen, Bartlett and Channell2021) and in the use of humour to induce positive affect and increase the patient's engagement with treatment and the therapist's work satisfaction (Consoli Reference Consoli, Blears and Bunge2018).

During recent decades, two major premises of reciprocal inhibition have been challenged: first, graded imaginal exposure was found to be equally effective whether combined with relaxation or not; and second, ungraded exposure was shown to be as effective as graded exposure, at least in those willing to undergo intense exposure (Craske Reference Craske, Liao and Vervliet2012). Moreover, exposure techniques (e.g. behavioural experiments) are at the core of Beckian cognitive therapy as a means of testing the validity of thoughts and eventually abandoning safety-seeking behaviours (Hofmann Reference Hofmann and Asmundson2008). Nevertheless, it is worth recalling that Joseph Wolpe's legacy was to establish many of the concepts that now constitute the bedrock of the most empirically supported model of psychotherapy, including the extinction of conditioned fears through (un)learning processes and the establishment of a therapeutic relationship in which the patient feels genuinely safe.

Acknowledgements

C.C. thanks Professor Dr Cristina Canavarro for her continuous encouragement and support, Professor Dr Ana Paula Matos for her many teachings on the practice of CBT, and Sara Almeida-Abrantes de Sousa, who greatly motivated the writing of this article.

Author contributions

C.C.: conceptualisation, resources, writing of the original draft, review and editing of final version, supervision/administration; K.R.: writing of the original draft; C.S.: validation, review and editing of the final version.

Funding

This study was supported by the Center for Research in Neuropsychology and Cognitive and Behavioral Intervention (UIDB/PSI/00730/2020), University of Coimbra, Portugal.

Declaration of interest

C.C. is a member of the BJPsych Advances editorial board but did not take part in the review or decision-making process of this article.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.