Charles Mercier's Lunatic Asylums: Their Organisation and Management is effectively a manual of how to run an asylum (Mercier Reference Mercier1894). It covers everything and anything related to asylums, from the practical and physical (sinks and curtains) to how they should be managed (an elaborate token economy is recommended). It is written in an ex cathedra style with no semblance of doubt or need to justify the exhortations with evidence at any sort or level, not even supporting statements and certainly no consideration of alternatives. In his preface to the book Mercier explicated this style as follows:

‘There are few departments of man's labour more completely specialised and more different from the rest than that which deals with the management of Lunatic Asylums. It is therefore somewhat remarkable that no system of instructions on this matter has hitherto been published, and that it has been left for the writer of this volume to be the first to treat the subject systematically’ (p. vii).

In addition to the often arcane detail the book is, at least at face value, a call for asylum inmates to be treated as individuals and with respect. Mercier longed for a time when ‘management of patients by the gross will give way to management of the individual’ (p. viii) and stressed that the medical superintendent ‘should remember that his first duty is the care and treatment of his patients [ … ] and unless this object is continually kept before his mind, he will be sure sooner or later to fall into one of the many pitfalls that beset his path’ (p. 199).

Mercier favoured an asylum in the pavilion style with a maximum of 600 beds divided, ideally, into wards of no more than 10 beds (with a maximum of 30 beds) and as many 4- or 5-bed units and single rooms as possible. This was written at a time when many asylums originally designed for much smaller numbers had expanded to 1000 beds or so and dormitories sleeping 40–60 inmates were commonplace. For Mercier, a key management objective was ‘to approximate the life of the insane to the life of the sane, as far as the approximation is possible’ (p. viii), so an asylum should have a ‘comfortable and home-like air’ (p. 48).

The other main theme of the book is his account of steps to avoid what we would now call institutionalisation. Mercier believed ‘that no restriction is justifiable that is not required by the circumstances of the individual case’ (p. vii) and that institutional life destroyed ‘feelings of self-respect’ and made many patients ‘wretched’ (p. viii). He warned against ‘the love of idleness [that] grows by indulgence, until all inclination to work disappears’ (p. 85).

The book was well received and widely read, many asylums apparently purchasing a copy. This was also the case in faraway New Zealand, and Brunton (Reference Brunton2003) documents the widespread influence of the volume there. The book remained what MacArthur (Reference MacArthur1921) described as the ‘standard’ on the subject until at least the 1920s.

Brief biography

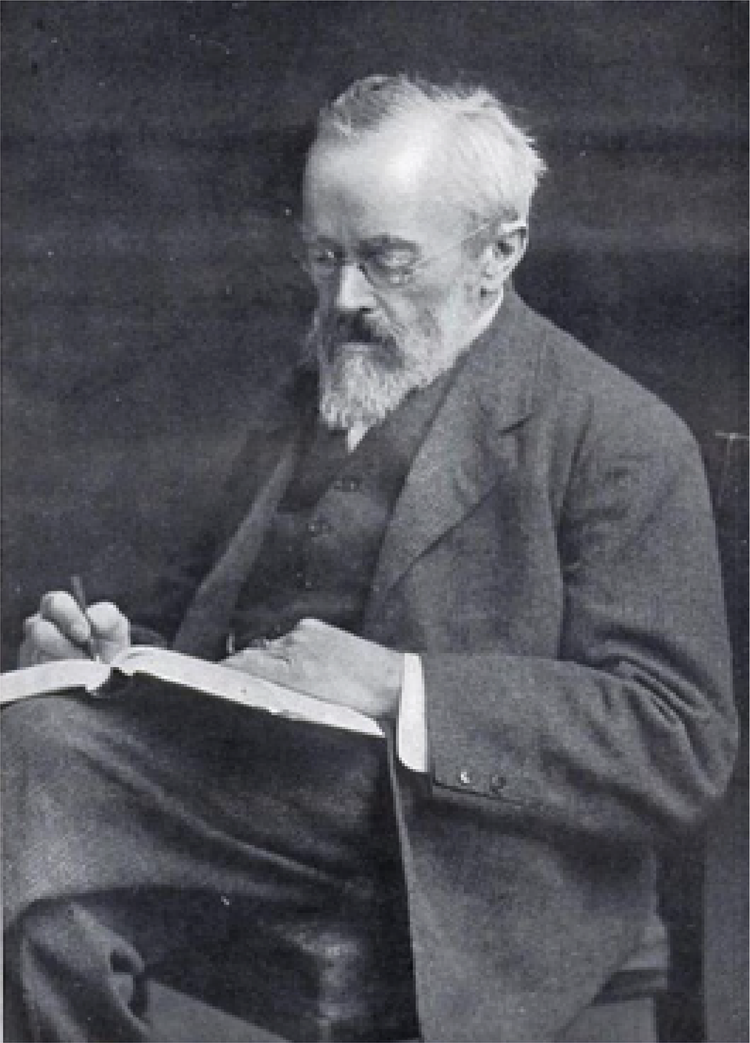

Charles Mercier (Fig. 1) has an interesting biography, which is documented in an obituary by Sir Bryan Donkin and an article by Paul Bowden (Donkin Reference Donkin1920; Bowden Reference Bowden1994). In brief, he was born into a middle-class family and attended a prestigious private school, which he had to leave at a young age on the death of his father. He decamped for the sea and was a cabin boy on a ship bound for Morocco. On return, he worked as a clerk in a warehouse, but somehow or other got himself into medical school at the London Hospital, qualifying in 1874. Apparently, he was a top student, and in his final Bachelor of Medicine examination he won London University's gold medal for Mental Science (Brown Reference Brown1955). In 1878, he obtained a Fellowship of the Royal College of Surgeons (FRCS) and became superintendent of the Bethel Hospital, as well as surgeon at the Jenny Lind Hospital and the Lying-In Charity, all in Norwich, UK (Brown Reference Brown1955). He also lectured, first on neurology and insanity at Westminster Hospital in London, UK, and then on psychological medicine from 1906 to 1913 at Charing Cross Hospital, London, UK, where he was also physician for mental diseases (Brown Reference Brown1955). He was for a long time physician in charge of a private asylum in London and had a practice in Wimpole Street. In 1894, Mercier was elected secretary of a committee of the Medico-Psychological Association (the forerunner of the present Royal College of Psychiatrists) and became its President in 1908.

FIG 1 Charles Mercier in Reference Mercier1919. (Image in the public domain. Source: Wikipedia.)

An expert, but a controversialist

Mercier was particularly interested in forensic psychiatry, and he was influential in developing societies in that discipline. He penned numerous prize-winning books on this topic and his insights were much lauded. Clouston described Mercier and Henry Maudsley as ‘men [ … ] who have touched the highest point of literary style, of expert knowledge’ (Clouston Reference Clouston1912).

However, several contemporary observers and subsequent scholars have noted that although Mercier was extremely bright and able, he was also a controversialist. Brown (Reference Brown1955) described him as ‘a man of wide reading and mordant wit [who] revelled in controversy’ (p. 463) and Sir William Osler, in his obituary notice, wrote of him: ‘With a rich vocabulary and a keen wit he had no equal among us as a controversialist’ (Osler Reference Osler1919). He seemed to go out of his way to be dogmatic and challenging and he declaimed on all sorts of topics, some far from the topic of psychiatry, for example vegetarianism (Mercier Reference Mercier1916) and spiritualism, particularly satirising the latter (Mercier Reference Mercier1919). In a lecture at the University of Oxford, he argued the uselessness of taught logic and accused Aristotle as having done irreparable damage to the human mind (Brown Reference Brown1955). He wrote a piece during the Great War, describing the ‘irrelevance’ of Christian doctrine to the case for or against war (Mercier Reference Mercier1918). One might think this was far from his area of expertise so that caution might be the order of the day – not a bit of it, each sentence is written with polemical certitude! He was extremely negative about homosexuality, describing it as a ‘perversion’ and its practitioners as ‘abnormal beings’ (Crozier Reference Crozier2008). Crozier also documents how these latter views, while perhaps not unusual in Victorian society, pervade many of Mercier's books and articles, though not Lunatic Asylums: Their Organisation and Management, where he is preoccupied with a separation of the different sexes.

In relation to psychiatry, Mercier was often caustic in his criticism, and he seemed to delight in attacking established figures. He fell out with and was much criticised by contemporary luminaries such as Conolly Norman and David Yellowlees. Maudsley was a major figure of the late Victorian psychiatry establishment but, according to Scull et al (Reference Scull, MacKenzie and Hervey1998: p. 254), he was ‘savagely taken apart’ by Mercier who, in the pages of the prestigious journal Brain, ‘mocked [ … ] mercilessly’ Maudsley's efforts to ‘“physiologize” the mind’. Mercier was also zealously anti-psychoanalytical. Bowden describes Mercier as a ‘self-confessed Freud hater’ and shows how this was strongly linked to his anti-German sentiments. Mercier believed German psychiatry, particularly as represented by Kraepelin, was rotten. He campaigned to have analysis condemned as morally corrupting and described a recent book on psychoanalysis as ‘the new pornography’ (Bowden Reference Bowden1994). Like many others of his day, Mercier believed in degeneration theory and the limitations that imposed on the rights of the mentally ill, but these ideas were mainstream at the time and Mercier did not seem to advocate positive actions to promote eugenics in his writing.

Conclusion

To our contemporary ears Mercier's dogmatism and trenchant views sound harsh and unnecessarily acerbic. Claire Hilton (Reference Hilton2019) in her insightful blog notes that his language can seem as ‘archaic, patronising and sexist’ but encourages us not to be put off by it, citing the humanitarian ideas he expressed and pointing out that he should be judged in the context of his time and not retrospectively. Bowden is not so kind and opines that in Mercier's books ‘Metaphors and analogies abound and generalisations from them are advanced as theories which are themselves presented as scientific facts. The whole is pervaded by a sense of emptiness because it is totally devoid of psychological understanding’ (Bowden Reference Bowden1994).

So, what of the volume under consideration here? I am more inclined to align with the negative view and support Bowden's critique that Mercier's ideas are simply presented as facts. It is true that this style was commonplace at the time, but he is clearly able enough to see that such a certain approach without qualification is essentially inimical to the academic process and indeed he was an academic himself. Although humanitarian ideals are expressed in this volume, one is left with the feeling that, to Mercier, asylums and their inmates were products, commodities. Sympathy and empathy do not abound. The token economy he espouses in the book is purported to be therapeutic and to encourage activity, but he clearly describes another major benefit in that its non-award can be used as punishment. It is interesting to note that despite this book being a standard, the humanitarian ideals it espouses and the token economy it promoted were not, by and large, taken up until some considerable time thereafter. Perhaps Mercier's reputation as a controversialist worked against him? Against that, he became President of the Medico-Psychological Association. So, to some extent Mercier remains an enigma: great mind or self-promoter or both? But his book is worth reading for the insights into and rich flavour of Victorian psychiatry it affords.

Acknowledgement

Dr Claire Hilton is thanked for her helpful comments on earlier drafts and for providing useful references.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.