LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this article you will be able to:

• understand how to approach applications to the tribunal for patients detained in hospital

• differentiate between capacity to bring and capacity to conduct proceedings

• decide when to consider use of section 67 of the Mental Health Act.

Assessments of an individual's decision-making capacity are important judgements that are required to be made at different points during a person's in-patient psychiatric admission and detention for treatment in England and Wales. For example:

• prior to and following admission, an assessment needs to be made in relation to the person's capacity to consent to admission and treatment for mental disorder;

• for those detained under a section of the Mental Health Act 1983 (MHA) there is a statutory requirement to assess capacity preceding the ‘3-month rule’ under section 58 in relation to medication for mental disorder;

• capacity to decide whether or not to obtain help from an independent mental health advocate (IMHA) will need to be made and, if capacity is lacking, the clinician should attend the patient to explain the IMHA's role (Department of Health 2015a);

• in relation to the First-tier Tribunal (Health, Education and Social Care Chamber) (Mental Health) in England (the Mental Health Review Tribunal in Wales) (the tribunal) a practice direction requires that reports submitted by the responsible clinician contain a ‘summary of the patient's current progress, behaviour, capacity and insight’ (Tribunals Judiciary 2013). This article does not cover the process in Scotland and Northern Ireland, both of which have their own, distinct, Mental Health Acts and tribunals.

The tribunal is the legal forum which determines whether the grounds for detention under the MHA exist. It is the means by which a patient can challenge their deprivation of liberty, as per their right set out in Article 5.4 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). The tribunal is empowered to direct the patient's release, even in the face of evidence from the clinical team that further detention is required. As with all courts and tribunals, there are practice directions and rules, the purpose of which is to address how the process should work (Tribunal Procedure (First-tier Tribunal) (Health, Education and Social Care) Rules 2008 (SI 2008/2699)). It is important to note that the tribunal has a very limited jurisdiction, which is set out in the MHA (Part V). It has no powers outside those clearly delineated in the MHA itself.

Just a point on terminology, the tribunal used to be called the Mental Health Review Tribunal across England and Wales. It is now called the First-tier Tribunal in England but remains the Mental Health Review Tribunal in Wales. Very little rests on that differentiation and for the purposes of this article we will refer to ‘the tribunal’ as covering both the First-tier Tribunal and the Mental Health Review Tribunal.

Guidance for clinicians in relation to processes and requirements for the tribunal is available elsewhere (Brindle Reference Brindle, Bhugra, Bell and Burns2016). Assessments of capacity must be made applying the principles set out in the Mental Capacity Act 2005 (MCA), including the initial presumption that the patient has the relevant capacity. The identification of the specific decision that is the subject of the capacity assessment is the important first step because it identifies the nature of the information that the patient has to sufficiently retain, understand and use or weigh (as required in section 3 of the MCA). The theme of capacity has emerged as a thread through a number of legal cases in the Upper Tribunal (defined below). These cases provide guidance on how the clinician should apply the statutory test contained in the MCA. The relevance to clinical practice is that there are different decisions for which capacity may need to be assessed in relation to a patient's application to, and representation at, the tribunal. These are as follows:

• does the patient have the capacity to apply to the tribunal to challenge his or her detention in hospital?

• does the patient have the capacity to appoint a representative for the purpose of the tribunal?

• does the patient have the capacity to conduct the proceedings him- or herself?

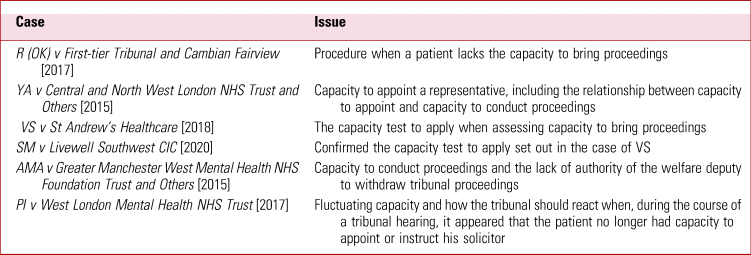

These guidance cases on capacity (Table 1) help us differentiate: the nature of the decisions that need to be made; the content of capacity assessments; and how to act on the results of such determinations. Hence capacity assessments that are undertaken by clinicians may influence the conduct of tribunal proceedings but may also be subject to scrutiny and, possibly, challenge. In light of the above, demonstrating how the principles of the MCA have been followed (for example in how decision-making has been supported), identifying the information relevant to the decision, and justifying and appropriate recording of assessments are all important. The most relevant cases are discussed below, and we outline a scheme to help clinicians follow that judicial guidance.

TABLE 1 Cases and issues in the Upper Tribunal relating to capacity

Process: applications and referrals to the tribunal

There has been a mental health tribunal for many years, but the Tribunals Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 modernised the whole of the tribunal system (not just the mental health tribunal) and brought about a number of helpful changes. Two of those changes are of note for our purposes:

• it took the mental health tribunal away from the Department of Health and placed it under the oversight, as with all other courts and tribunals, of the Ministry of Justice;

• it created a two-tier system: a first tier and an upper tier, with the upper tier hearing appeals from the first tier on points of law. One of the benefits of the latter is that, in determining appeals from the first tier, the upper tier tribunal (Upper Tribunal) has the opportunity to provide guidance as to the application of the law and procedure and it is the guidance of that tribunal in respect of capacity that we will focus on here.

The ECHR permits signatory states to deprive their citizens of their liberty if those individuals have a mental disorder of such a degree that compulsory in-patient admission for treatment is required (Winterwerp v Netherlands 6301/73 [1979]). The state must permit the detainee to challenge that deprivation at intervals. The MHA deals with this by permitting one application may be made by a patient to the tribunal in what are known as eligibility periods. These periods vary from section to section and are listed, along with other matters, including the circumstances in which the nearest relative may apply to the tribunal, in Chapter 6 of the reference guide to the MHA (Department of Health 2015b).

The MHA goes beyond the requirement set out in Article 5.4 of the ECHR, in that it also provides a safeguard for those patients who may not have the wherewithal or motivation to exercise their right of challenge. There are certain specified patients for whom ‘hospital managers’ have a duty to refer to the tribunal (MHA, section 68). A similar duty rests on the Secretary of State for Justice in relation to restricted patients (mentally disordered offenders detained in hospital for treatment subject to a restriction order/direction) (MHA, section 71). Finally, there is a third process by which a patient's detention may be reviewed by the tribunal and that is by way of the exercise of discretion by the Secretary of State. Under section 67 of the MHA, the Secretary of State for Health may, at any time, refer patients who are detained in hospital, who are subject to a community treatment order (CTO) or who are subject to guardianship under part II (and some unrestricted patients under part III) of the Act. Again, section 71 provides a similar discretion in respect of restricted patients. We will discuss the procedure relating to this power below.

Furthermore, the MHA Code of Practice (para. 12.6) specifies that hospital managers (and the local authority in guardianship cases) are under a duty to take steps to ensure that patients understand their rights to apply for a tribunal hearing (refer to the statutory duty of managers of hospitals under section 132 of the MHA). That safeguard was bolstered when the MHA was amended in 2007, with the introduction of a statutory advocate in the form of an IMHA. Thereafter, the process of appeal includes completion of the application to the tribunal with the prescribed information by the patient or, under certain circumstances, the nearest relative or another professional who is authorised to do so.

Differentiating capacity to ‘bring proceedings’ and ‘conduct proceedings’

Capacity to bring proceedings

Before considering the capacity ‘tests’, the first case that we will discuss is R (OK) v First-tier Tribunal and Cambian Fairview [2017]), which highlights the predicament of many clinical staff who may be trying to act in a patient's best interests in applying to the tribunal on his or her behalf. In this case, a solicitor submitted an application on behalf of a person detained for psychiatric treatment under section 3 of the MHA. The application was signed not by the patient but by the solicitor, who stated that the patient had personally authorised this. It was accepted that the patient lacked the capacity to make such an application. The tribunal rules, however, require the application to be signed by the patient or someone authorised to do so (SI 2008/2699: rule 32). Ultimately, the application was struck out because the lack of compliance with that rule meant it was invalid.

The patient, via their solicitor, appealed that decision to the Upper Tribunal, but it was unsuccessful. The Upper Tribunal judge agreed that the case should have been struck out on the basis that the failure to comply with the rules was to ‘deprive the tribunal of jurisdiction’ (rule 8). It was argued that there was a gap in the legislation in that it failed to provide for patients who lack the capacity to decide to apply to the First-tier Tribunal. That argument was rejected, as an application to the Secretary of State to refer the case under section 67 of the MHA could have been made. In our experience, in older people's services, it is common for individuals with severe dementia who are detained in hospital to lack the relevant capacity. Historically, it has been common practice for nurses to make an application on a patient's behalf (should they appear to object to their detention) but it is evident from this case that it may not be lawful to do so.

The second case is the Upper Tribunal case of VS v St Andrew's Healthcare [2018] (Box 1), in which the specific issue was the ability of the patient to bring proceedings before the tribunal. This case highlighted that there is a distinction between the ability of someone to ‘bring proceedings’ (or make an application) and the ability to ‘conduct proceedings’ (or instruct their representative) discussed below. The Upper Tribunal considered that a much lower threshold was required to satisfy the requirements of capacity to bring proceedings before the tribunal than to conduct them. For example, in this case the patient was able to clearly retain the understanding that he was being held somewhere he did not want to be, and he ‘repeatedly demonstrated’ his unhappiness with that. The judge held that to make a valid application to the tribunal the correct test to apply was whether the patient could understand the following:

• that they are being detained against their wishes

• that the tribunal is a body that would be able to decide whether they should be released.

BOX 1 The case of VS v St Andrew's Healthcare [2018]

• The patient's responsible clinician had reported that the patient had demonstrated on multiple occasions that he did not wish to remain an in-patient in the hospital and wanted to be discharged.

• The patient made an application to the First-tier Tribunal, which he filled out with the assistance of a Lithuanian-speaking healthcare assistant.

• When the possibility of appealing against his treatment and in-patient admission via the tribunal was explained to him, the patient understood that this was a possible avenue for his discharge.

• Although the treating team considered the patient to be lacking capacity to fully understand the need for in-patient treatment, they were of the view that he was able to broadly demonstrate his understanding that an application to the tribunal might result in his discharge.

• The First-tier Tribunal had appointed a solicitor to represent the patient. The solicitor later raised concerns about the patient's capacity that resulted in this matter coming before the First-tier Tribunal and subsequently the Upper Tribunal.

• The patient's solicitor was concerned that the patient told her that he wanted to be discharged so that he could have a cigarette. He could not understand that he was being held in hospital and could not retain information about the purpose, procedure and powers of the tribunal.

The more detailed and demanding requirements for capacity to conduct proceedings were not relevant at the stage of making an application. This approach, or test, has been confirmed in a subsequent Upper Tribunal case (SM v Livewell Southwest CIC [2020]).

Capacity to conduct proceedings

The judge in a further case (YA v Central and North West London NHS Trust and Others [2015]) drew a distinction between the ‘capacity to appoint a representative’ and the ‘capacity to conduct proceedings’. He indicated, however, that this distinction ‘narrows’ and can be ‘theoretical rather than real’. In general, it is perhaps as well not to dwell on the differences and for most purposes to assume that they are the same. The judge indicated that that the capacity required to conduct proceedings may be a relatively demanding hurdle but will depend on the facts of any individual case. Therefore, in relation to conducting proceedings, the judge noted (at para. 58):

‘factors that the patient will have to be able to sufficiently retain, understand, use and weigh will be likely to include the following:

i) the detention, and so the reasons for it, can be challenged in proceedings before the tribunal who, on that challenge, will consider whether the detention is justified by the provisions of the MHA,

ii) in doing that, the tribunal will investigate and invite and consider questions and argument on the issues, the medical and other evidence and the legal issues,

iii) the tribunal can discharge the section and so bring the detention to an end,

iv) representation would be free,

v) discussion can take place with the patient and the representative before and so without the pressure of a hearing,

vi) having regard to that discussion, a representative would be able to question witnesses and argue the case on the facts and the law, and thereby assist in ensuring that the tribunal took all relevant factual and legal issues into account,

vii) he or she may not be able to do this so well because of their personal involvement and the nature and complication of some of the issues (e.g. when they are finely balanced or depend on the likelihood of the patient's compliance with assessment or treatment or relate to what is the least restrictive available way of best achieving the proposed assessment or treatment),

viii) having regard to the issues of fact and law his or her ability to conduct the proceedings without help, and so

ix) the impact of these factors on the choice to be made.’

The significance of this in practice is that where a patient has not appointed a representative to act for them before the tribunal, the tribunal rules (SI 2008/2699) mean that a National Health Service trust or health board (or independent provider) may be directed to determine whether the person is capable of doing so and the responsible clinician (usually, but not a specific requirement) completes an MH3 form (see below).

Should the patient be assessed as lacking the required capacity, then the tribunal rules (SI 2008/2699) are applied. The tribunal utilises rule 11(7)b (Box 2) if it is satisfied that the patient lacks the capacity to conduct the proceedings, i.e. they lack the capacity to instruct a representative. The position for the solicitor (or other representative) when appointed under rule 11(7)(b) is somewhat different from that when acting on instructions. There is a general requirement to act in the best interests of a person who lacks relevant capacity. The appointment enables the solicitor to act for the patient in their best interests. In order to do so, the solicitor must ascertain their views, wishes, feelings, beliefs and values and give those considerable weight when making any representations on their behalf. As a minimum, the solicitor will act to ensure that the statutory criteria are fully tested on behalf of the patient. The Law Society provides guidance on how this ought to be done (Law Society 2019).

BOX 2 Tribunal rule 11(7) relating to the appointment of legal representatives

In mental health cases in England and Wales (Tribunals Judiciary 2013), the tribunal has the power to appoint a legal representative on behalf of an unrepresented patient where:

(a) the patient has stated that they do not wish to conduct their own case or that they wish to be represented; or

(b) the patient lacks the capacity to appoint a representative but the tribunal believes that it is in the patient's best interests for them to be represented.

This power is found at rule 11(7) of the Tribunal Procedure Rules 2008 (SI 2008/2699) or rule 13(5) of the Mental Health Review Tribunal for Wales Rules 2008 (SI 2008/2705)

What to do?

These cases highlight what may be an issue in many in-patient settings: a potential clash between the actions of clinicians attempting to protect the rights of patients and how the law currently stands. The following outlines our recommended process to strike the necessary balance between rights and procedures and is summarised in Box 3.

BOX 3 Stages in the application and appeal process

Stage 1: Inform the patient and nearest relative of rights to apply to the tribunal

Stage 2: Assess capacity to bring proceedings

Stage 3: Assess capacity to conduct proceedings

Stage 4: Consider use of section 67

Stage 5: Keep capacity under review

Stage 1: informing the patient of rights to apply to the tribunal

Staff in the trust should make every effort to help the patient both access an IMHA and, either directly or via their advocate, understand their rights in order to support the appeal against their detention (MHA, section 132). This should include information about timescales and their entitlement to free legal advice and representation. The information must be provided when the patients are first detained in hospital and whenever their detention is renewed or when their status under the MHA changes, for example if they move from detention under section 2 to detention under section 3. The patient's permission should be sought to provide the information to their nearest relative unless there is a specific reason not to do so. It may be necessary to provide the information in a language or format that the patient can easily understand, perhaps using a professional interpreter or translator.

IMHAs could provide support and information needed following detention in hospital. The advocate can go through the patient's right in detail, including the right of appeal. Thereafter the process of appeal includes completion of the application form to the tribunal by the patient, another professional authorised to do so or, under certain limited circumstances, the nearest relative. The application requires the patient's details, the MHA section under which they are detained, the name of the hospital where they are detained, the name of the community supervisor or care coordinator, and details of the nearest relative and legal representative. The application is then signed by the patient or someone authorised, by the patient, to do so.

Stage 2: assess capacity to bring proceedings

At the time of making the application, consider the patient's capacity to bring proceedings. If the patient's capacity to challenge their detention and make an application is not clear, then the next step is to assess their capacity in accordance with the MCA (sections 1–3). The test in VS v St Andrew's Healthcare [2018] is based on the person's understanding of two issues in broad terms, simple language and deliberately framed at a low level. To reiterate, the patient must understand:

• first, that they are being detained against their wishes, and

• second, that the tribunal is a body that will be able to decide whether they should be released.

If the patient is deemed to have capacity, the nursing team, or the IMHA, can then submit the application form on their behalf. The patient does not need to understand other procedures or powers of the tribunal and their understanding of their right of withdrawal from proceedings does not form part of the test. If the patient lacks capacity, then an application should not be made and section 67 should be used as described below (stage 4).

If the tribunal considers that a patient's capacity has changed or fluctuated such that they lacked capacity at the time of the application but have capacity at the time of the hearing, it should consider inviting them to make a fresh application (see SM v Livewell Southwest CIC [2020]: para. 86).

Stage 3: assess capacity to conduct proceedings

The tribunal will expect patients to be legally represented at hearings unless they decide to represent themselves and have capacity to do so. Assuming an application has been lodged following the above assessment, as Judge Jacobs stressed in the case of VS, the capacity to bring proceedings is not the same as capacity to then conduct those proceedings (including instructing a solicitor). If capacity to conduct proceedings is in doubt it is helpful to identify this as early as possible, certainly in reports but also through the MHA administration department. If the patient lacks capacity, then the tribunal can be informed (via the MH3 form) that the clinical view is that the patient lacks the necessary capacity. As indicated, the tribunal will then appoint a lawyer to act on behalf of the patient. It may be that the patient's representative has identified capacity issues, which will instigate the request for completion of an MH3 form.

The content of the MH3 form is outlined in Box 4. It requires a yes/no statement as to whether the patient lacks the capacity to appoint a legal representative. The guidance provided is not exactly the same as that in YA v Central and North West London NHS Trust and Others [2015]; notwithstanding, the clinical team should identify the information that is relevant to the particular patient and how support should be provided to help the individual make the decision. The information may therefore include whether they understand that they would not have to pay for a lawyer; that the lawyer would represent them and be independent of the hospital and that discussions with the layer would be confidential; and that being represented by a lawyer in the proceedings might be to their advantage. If the patient meets the requirements of that test, then they may have the capacity to instruct their own lawyer. If they lack capacity to decide, strictly speaking, the clinical team will be responsible for carrying out a best interests assessment to establish whether it is thought to be in the patient's best interests that a legal representative be appointed on their behalf. However, it is difficult to conceive of circumstances in which it would not be in a person's best interests to be represented. Note that in hospital managers’ hearings there is no equivalent to tribunal rule 11. Therefore, if the patient lacks the capacity to decide whether to appoint legal representation or represent themselves at a hospital managers’ hearing, the trust may not be in a position to appoint a legal representative on the patient's behalf. In those circumstances, a referral to the IMHA service will likely be necessary.

BOX 4 Content of the MH3 capacity assessment form

The MH3 includes the following questions:

• ‘Does the patient lack the mental capacity to make a decision as to whether they wish to be represented before the tribunal?’ (Yes/no).

• ‘If lacking capacity is it your assessment that it would be in the best interests of the patient to be represented’ (and provide reasons if not).

• ‘In any case where you assess that the patient does have capacity to make a decision to appoint a representative, has the patient stated either that they do not wish to conduct their own case or that they wish to be represented (in either case the tribunal may appoint a representative for them)?’ (Yes/no)

The form provides the following guidance:

‘A patient who has impairment or disturbance to the functioning of his/her brain or mind probably lacks capacity to make a decision to appoint a representative if the answer is ‘No’ to one or more of the following non-exhaustive list of questions:

(a) Does the patient understand what a tribunal hearing is?

(b) Does the patient understand what the tribunal's powers are (e.g. to discharge the Section/order)?

(c) Does the patient understand the purpose and role of the representative (e.g. to question the clinical team on the patient's behalf and tell the panel what the patient's views are)

(d) Can the patient assess the consequences of their decision one way or the other (e.g. appreciate that if they are not represented their chances of being discharged may not be as good as they would be with a representative, because the clinical team will not be challenged and the tribunal may not know what the patient wants)

(e) Can the patient communicate their decision sufficiently clearly to be understood?’

For capacity assessments the clinical team should follow their trust's policy in relation to documentation and make certain that they abide by the practice direction requirements for producing reports for the tribunal (Tribunals Judiciary 2013). In one Upper Tribunal case the Judge made the following statement: ‘I observe that, while a number of clinicians have addressed Mr M's mental capacity in various decision-making contexts, the Tribunal appeal papers do not contain any document embodying a formal mental capacity assessment’ (M v Abertawe Bro Morgannwg University Health Board [2018]: para. 7). Therefore, to avoid any doubt or criticism we advise assiduous attention to detail regarding conduct and recording of assessments and incorporation of labours and observations in any submissions to the tribunal.

Stage 4: use of section 67 (or section 71) of the MHA

Despite the above, if the members of the clinical team were concerned that the patient lacks capacity to apply and feel that, nevertheless, the person would benefit from a review of the criteria by the tribunal, then the following should be considered.

1 Is the patient due to be referred to the tribunal?

Hospital managers have a duty to refer a patient to the tribunal:

• after 6 months of detention (including time on section 2) if the patient is detained under section 3 and has not applied

• every 3 years if the patient has not applied since the date of the last tribunal

• every 12 months if the patient is under 18 years of age, and

• as soon as practicable when a CTO has been revoked.

If one of these criteria is met, then their case will be referred to the tribunal in any event (section 68) and no further action will be required. There is a similar scheme in respect of restricted patients (e.g. the Secretary of State must refer a patient to the tribunal if they have been recalled to hospital following a conditional discharge).

2 If there is no referral imminent

If no referral is imminent, then it would be appropriate to contact the trust's MHA administration team asking that they make a request of the Department of Health by setting out the reasons why it is felt appropriate that there should be tribunal proceedings. The Department of Health team are then requested to make a referral to the tribunal in accordance with section 67 of the MHA. Anyone may ask the Secretary of State for Health to make a reference for any reason at any time. Indeed, the MHA Code of Practice states that hospital managers should raise this possibility with the Secretary of State if, among other reasons, the patient lacks capacity to do so (Department of Health 2015a). It may be that the IMHA who has seen the patient is well suited to make the suggestion to the Secretary of State. Indeed, a further possibility is that, if the circumstances arose, the tribunal itself could expedite proceedings by seeing whether the Secretary of State wished to make a referral.

3 Best interests review

As a result of the case law reviewed in this article the guidance has recently changed. If the tribunal forms the view that the patient never had capacity to make an application it must strike the case out. However, the tribunal can now ask the parties whether they would argue that it would nevertheless be in the patient's best interests to review the criteria. The tribunal judge can then adjourn and contact the Department of Health to ask for a reference to be made to the tribunal (exercising the Secretary of State's powers under section 67). The process may even be quick enough for the tribunal to have to adjourn for only an hour or so and determine the case the same day. This improved procedure still maintains the position that applications should not be made where a patient lacks capacity to bring proceedings (with the exceptions in points 1 and 2 above), but preserves the ability of the tribunal to review the criteria if an inappropriately made application sneaks through.

In current practice, such requests are most commonly made:

• in cases where a patient detained under section 2 misses the 14-day deadline for applying to the tribunal and there is still time for a hearing to be arranged before the section 2 is due to expire;

• if a patient's detention under section 2 has been extended pending resolution of proceedings under section 29 to displace their nearest relative. The MHA does not give patients the right to apply directly to the tribunal in these circumstances (R (H) v Secretary of State for Health [2006]).

Stage 5: Keep capacity under review

The case of PI v West London Mental Health NHS Trust [2017] reminded us all to keep capacity under review at all times during tribunal proceedings. In that case, the patient had capacity to apply and had capacity to instruct but owing to psychotic symptoms during the hearing lost capacity and there was a need for the tribunal to appoint the lawyer under tribunal rule 11(7)(b) midway through the hearing.

Conclusions

Tribunal rules and judgments are not always easy to follow. One example is that tribunal rule 7 states: ‘An irregularity resulting from a failure to comply with any requirement in these Rules, a practice direction or a direction, does not of itself render void the proceedings or any step taken in the proceedings’ (SI 2008/2699). If a party has failed to comply with a requirement the Upper Tribunal ‘may take such action as it considers just’, which includes waiving the requirement, requiring the failure to be remedied or exercising its power under rule 8 (striking out a party's case). As it transpires, and which may be counterintuitive to clinicians, when someone lacks capacity to bring proceedings it is rule 8 that has prevailed. These cases in the Upper Tribunal have the potential to change what was accepted (although technically incorrect) practice such that staff cannot make applications directly to the tribunal on behalf of patients who lack capacity to make that decision and, if no alternative is available, must therefore rely on section 67 of the MHA. They highlight the different decisions that must be made by a patient bringing or conducting proceedings when appealing detention under the MHA, thereby clarifying the practice of clinicians in supporting that important safeguard.

Author contributions

All the authors have contributed equally to the production of the manuscript, revising it critically and approving it.

Declaration of interest

None.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

1 A patient with advanced dementia with behavioural and psychological symptoms of dementia has been admitted under section 3 of the MHA to an in-patient unit. The nursing staff have made an application to the First-tier Tribunal on behalf of the patient, who may lack capacity. This application would be invalid if it were:

(a) signed by the patient

(b) signed by the nursing staff

(c) signed by the responsible clinician

(d) signed by a solicitor

(e) signed by a relative or carer.

2 A patient admitted under section 2 of the MHA has appealed against the detention. The patient is unaware that they do not need to pay for a lawyer to represent them. Assessing the patient's capacity to understand that they would not have to pay for a lawyer would be part of:

(a) capacity to bring proceedings

(b) litigation capacity

(c) financial capacity

(d) capacity to conduct proceedings

(e) mental capacity.

3 When assessing a patient's capacity to conduct proceedings in a tribunal, it is relevant to consider whether they understand:

(a) that a lawyer represents them free of charge

(b) that the lawyer is independent of the hospital

(c) that their discussions with the lawyer are confidential

(d) that they might be in an advantageous position if they are represented by a lawyer in the proceedings

(e) all of the above.

4 A patient has appealed against their section 3 treatment order and tribunal is being held. The capacity to understand that they are being detained against their wishes and that the tribunal is a body that would be able to decide whether they should be discharged would be part of:

(a) capacity to bring proceedings

(b) litigation capacity

(c) financial capacity

(d) capacity to conduct proceedings

(e) mental capacity.

5 Use of section 67 is not appropriate when the hospital managers have referred a patient to the tribunal in the following situation(s):

(a) after 6 months of detention (including time on section 2) if the patient is detained under section 3 and has not applied

(b) every 3 years if the patient has not applied since the date of the last tribunal

(c) every 12 months if the patient is under 18 years of age

(d) as soon as practicable when a CTO has been revoked

(e) all of the above.

MCQ answers

1 a 2 d 3 e 4 a 5 e

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.