LEARNING OBJECTIVES

After reading this article you will be able to:

• understand the differences between coaching and mentoring

• appreciate the scope of coaching and mentoring in professional psychiatric life

• demonstrate awareness of useful questions that can be used in coaching and mentoring practice.

Atul Gawande, a surgeon and professor of public health, delivered a TED talk in April 2017 called ‘Want to get great at something? Get a coach’ (Gawande Reference Gawande2017). He begins his talk by describing an innovation in coaching by training nurses to observe other nurses acting as birth attendants in rural India. The way the local birth attendants were handling infected material was leading to significant mortality. The coaching intervention completely reversed this trend and the approach of the coaches was found to be just right in facilitating change rather than imposing change from outside. This was transformative in delivering better care.

What has this got to do with the professional development of psychiatrists? The connection is, of course, coaching (or mentoring), but it also symbolises the way psychiatrists often naturally seek to influence beneficial change in indirect ways.

In the UK in 2003, Dean wrote a brief editorial for Advances in Psychiatric Treatment about the importance of having a mentor for newly appointed consultants (Dean Reference Dean2003). This will be the main context of thinking about coaching and mentoring for many psychiatrists. In the sister journal Psychiatric Bulletin, Roberts et al (Reference Mendel and MacDonald-Davis2002) had written about mentoring for new consultants in order to mitigate against isolation and the erosion of professionalism; and later Dutta et al (Reference Dutta, Hawkes and Iversen2010) wrote on how mentoring can have an important effect on personal development, career guidance and research productivity for female academics, who are not well represented in medicine or psychiatry.

Otherwise, very little has been published on the scope of coaching and mentoring within psychiatry in the UK. Coaching and mentoring are, however, approaches that are widely used in the private sector, such as in business (Whitmore Reference Starr2017).

An English-language literature search between the years 2009 and 2019 using PsycINFO yielded about 30 papers, of which several are relevant to this review: and these reveal a much keener interest in the field in the USA and Australia. Teshima et al (Reference Rao, How and Ton2019), for example, describe the consecutive challenges faced during the course of an academic career and how mentoring has a role at each stage to develop clinical and academic identity, leadership, and changes in roles and power. Ahn & Ziedonis (Reference Ahn and Ziedonis2019) highlight the usefulness of coaches in supporting psychiatrists so that mentors can concentrate giving their guidance on content expertise. Szabo et al (Reference O'Neill2019) describe a mentoring programme established in Australia to reduce stress and burnout among first-year trainees; and Rao et al take the view in their paper (2018) that purposeful efforts are needed to ‘recruit, mentor, and retain underrepresented students, residents, and faculty within the field of psychiatry to improve the quality of mental health care’. The benefits of mentoring to psychiatric recruitment are extolled by Harper & Roman (Reference West and Coia2017); and finally Guerrero & Brenner (Reference Gawande2016), in an editorial, emphasise how key mentorship is in ensuring creativity and innovation in order to prepare the workforce in an ever-changing and demanding environment, to grow the workforce in research, education and administration, to diversify the workforce and to retain the workforce.

In spite of the apparent lack of UK writing on these topics, Viney & Harris (Reference Roberts, Moore and Coles2013) have written on coaching and mentoring as a chapter in Leadership in Psychiatry (Bhugra Reference Bhugra, Ruiz and Gupta2013), and there are useful guides published by NHS England (2014) and the London Leadership Academy (Reference Hawkins and Shohet2014). The Royal College of Psychiatrists too has established a mentoring champion, with information on mentoring on its website (www.rcpsych.ac.uk/members/supporting-you/mentoring-and-coaching).

This article is divided into two sections: part 1 provides some background and definitions, describes basic skills, lists the features of emotional intelligence, the process of contracting; the coaching questions and models, coaching supervision and evaluation; and part 2 discusses organisational context and challenges to implementing change and summarises applications. It is hoped that this information will provide psychiatric trainers with an overview of the topic in order to plan their own professional development and to have coaching and mentoring conversations with trainees.

Part 1

Background to coaching and mentoring

The context in which coaching and mentoring developed as a more individualised approach to organisational development in Britain arose in the 1990s. This coincided with an emphasis away from collective life to a more individualistic society. Sport has had a strong influence on the development of coaching and mentoring approaches and there has been an increasing interest in organisational psychology and employee motivation. One notable influence was the Inner Game of Tennis by Gallwey (Reference Gallwey1974), which was a very popular work cited by many opinion leaders in the coaching field, and it emphasised the role of enhancing concentration, confidence and will-power. As described in Downey's book (Reference Downey2014), interference gets in the way between potential and performance, and this is usually rooted in fear and doubt.

Another important milestone in the development of coaching and mentoring has been the publication of a number of books by Whitmore, who brought his experience of sporting success to bear on his formulation of the GROW model, which he co-created and described in the first edition of Coaching for Performance (1992), which is now in its fifth edition (Whitmore Reference Starr2017). This model is described below.

Coaching and mentoring can be seen to be on a spectrum, but it is useful to see how each of these words is separately defined. It is widely understood that coaches need not have first-hand experience of the coachee's line of work but in mentoring there is usually a pairing of a more skilled or experienced person with a less experienced person.

Coaching is ‘the art of facilitating the performance, learning and development of another’ (Downey Reference Downey2014: p. 39). There are a number of definitions, but the generally accepted view is that it is a non-directive form of development; that it focuses on improving performance and developing individual skills; that coaching activities have both organisational and individual goals; that it provides people with feedback on both strengths and weaknesses; and that usually it is for the short term.

It should be pointed out here that the lack of a precise definition of coaching is a source of confusion, and it is accepted that there is a degree of overlap between coaching and mentoring (see below).

The focus of the coach is therefore facilitating learning and development through the conversation with the coachee. The role of the coach is as an equal and not to give advice and the coach will not be a subject specialist. The process of coaching will often be a focus on a short-term goal or goals. The environment of the coach is that they will be an independent individual, separate from the organisation.

Within coaching different categories are described, such as business coaching, life coaching and executive coaching.

Mentoring is ‘sharing expertise and some guidance’ (Whitmore Reference Starr2017: p. 249). Mentoring involves a more experienced person using their greater knowledge and understanding of the work, or of the workplace, to support the development of a less experienced employee. The term mentor appears to derive from a work in the 17th century that drew attention to the role of Mentor in the play Odysseus by Homer. Mentor is an older friend of Odysseus, who acted in a way that demonstrated wisdom and guidance.

Mentoring involves the long-term development of an individual. It is an essentially supportive form of development; it focuses on helping an individual manage their career and improve their skills; enables them to discuss some personal problems; and can have both organisational and individual goals.

The focus of the mentor is the growth and longer-term development of the mentee, who is often less experienced than the mentor. This contrasts with the focus of the coach, which is facilitating learning and development through the conversation with the coachee and which may not concern longer-term development.

The role of the mentor may include the giving of advice and the mentor will often be more experienced in the subject than the mentee (in contrast to the role of the coach, who has a more equal relationship with the coachee, will not give advice and will not be a subject specialist).

The environment of the mentor is that they will often be an individual who is part of the organisation that employs the mentee. This contrasts with the environment of the coach, who, as mentioned above, will be an independent individual separate from the organisation.

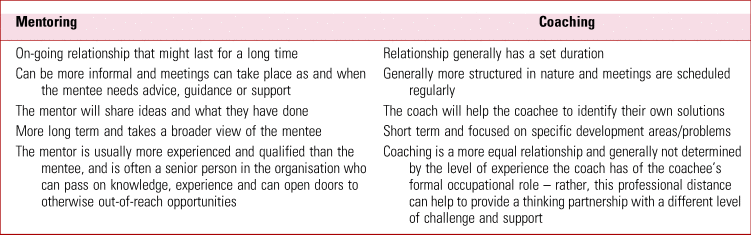

These differences are summarised in Table 1.

Table 1 Differences between mentoring and coaching

Source: London Leadership Academy (Reference Hawkins and Shohet2014).

In the Coaching and Mentoring Handbook (London Leadership Academy Reference Hawkins and Shohet2014), coaching and mentoring are described as ways of giving people time to think, and they are essentially both helping activities. They are not the same as training, although training may involve both or either of them. Neither are they the same as appraisal, educational supervision, teaching, counselling or therapy. The basic skills, the development of the relationships and the basic helping styles are common to both coaching and mentoring, and these will be dealt with consecutively below, after considering the coaching spectrum.

As pointed out in many texts there is a coaching spectrum, attributed to Downey (Reference Downey2003), and represented by a sliding scale of interventions, from helping a person find their own solutions in coaching to offering guidance in mentoring.

According to Clutterbuck (Reference Clutterbuck2014), the ideal characteristics of a good mentor describe someone who:

• already has a good record for developing other people

• has a genuine interest in seeing younger people advance and can relate to their problems

• has a wide range of current skills to pass on

• has a good understanding of the organisation, how it works and where it is going

• can combine patience with good interpersonal skills and an ability to work in an unstructured programme

• has sufficient time to devote to a relationship

• can command a mentee's respect

• has their own network of contacts and influence

• is still keen to learn.

Basic skills

These include active listening, listening orientation, the technique of reflection and using reflective listening. These can all be considered advanced communication skills common to both coaching and mentoring and are also skills that psychiatrists have in abundance.

These basic skills and qualities of communication are also reflected in the coaching and mentoring frameworks adhered to by organisations that train coaches. For example, the European Mentoring and Coaching Council (2020) describes a competence framework which is the result of extensive and collaborative research to identify the core competences of a professional coach and mentor. It lists eight competence categories across four levels. These eight core areas comprise:

• understanding self

• commitment to self-development

• managing the contract

• building the relationship

• enabling insight and learning

• outcome and action orientation

• use of models and techniques

• evaluation.

Starr (2008) gives more detail on the communication strategies required for being a skilled coach or mentor. These include building rapport, different levels of listening, using intuition, asking questions and giving supportive feedback. She also lists things that should not be done (p. 324), such as talking too much, seeking to dominate the conversation, trying to solve problems for the coachee, assuming the coach's or mentor's experience is relevant, and focusing on what not to do.

Emotional intelligence

No paper on coaching and mentoring would be able to avoid mentioning emotional intelligence, even though for the psychiatrist this may be a matter of somewhat obvious knowledge.

The term emotional intelligence was first popularised in Gorman's book of the same name in 1995, which makes the point that high emotional intelligence was supposed to confer a significant performance advantage on leaders (Goleman Reference Goleman1995).

Emotional intelligence has become a term used (somewhat vaguely) to describe personal and social skills. However, a more helpful approach is provided by Whitmore (Reference Starr2017), who explains how the competencies of emotional intelligence can be grouped into four domains: self-awareness, self-management, awareness of others and relationship management.

Starr (2008) prefers the term emotional maturity and uses this to describe our capacity to deal with our emotions.

Some useful definitions are provided in Box 1.

BOX 1 Some useful definitions in relation to emotional intelligence

Self-awareness: The ability to understand and recognise our moods, emotions and drives

Self-management: The ability to choose our responses and behaviour; how we handle change, stress and conflict

Awareness of others: Our ability to understand others’ emotional states: an ability closely linked to our ability to empathise

Relationship management: The ability to manage meaningful relationships (communicate clearly, collaborate, negotiate, deal with conflict, motivate and manage others)

Contracting

This is the process of making an agreement between coach and coachee (or mentor and mentee) on the basis of the relationship: the terms of engagement or ground rules. In any relationship, participants can make implicit assumptions about the purpose, the roles and the responsibilities of the other person involved. An explicit contract can set out the framework of the working relationship, can ensure that best use is made of the time available (that sessions do not degenerate into chat) and that the topics are covered that need to be covered.

The three major functions of the contract therefore are that it:

• ensures alignment: establishing focus, agreement on results, understanding and adjustment to individual needs, clarity of roles and responsibilities, and a common language

• establishes procedures: the coaching methods employed, time frames, boundaries and ground rules, some measurement of progress

• models the partnership: serves as an orientation to the partnership and forms the basis for disclosure, enquiry and commitment to the success of the relationship.

The contract might cover the coach as a practitioner and also the process of the coaching. It might include style (usually asking questions), parameters (e.g. the content of the conversations and how they are not going to be on specialist areas), tools, confidentiality (with a caveat that some things may be challenged or even shared with others if there were certain concerns; and whether or not there may be supervision with a supervisor), session times, follow-up and feedback (from the coachee to the coach).

Box 2 introduces a fictitious coach describing aspects of the coaching role, starting with contracting.

BOX 2 Case example: contracting

I phoned the coachee as arranged and went over the practical arrangements about using a colleague's office and that we would aim to meet for four sessions in total (but that this could be reviewed).

We had already established by e-mail that Thursday afternoons are best.

I said that I would bring a contract to the first meeting.

I checked that it would be alright with him to give him feedback as we went along.

I briefly mentioned that there were models that it might be helpful to use, and that I would be quite active in the sessions in reminding him of the goals he had set.

I explained that I would be making notes that I would share with him but that our sessions would of course be confidential except for the ordinary professional obligations that we all have concerning patient harm.

I would, however, be discussing some aspects of our sessions in supervision of my coaching and explained what this might look like.

Finally, I would be asking for feedback from him at the end.

He thought this was all rather formal but was happy to agree.

Although the process of contracting is a major consideration in any formal course on coaching and mentoring, within the trainer/trainee relationship this would normally be part of the usual learning or educational agreement established between the two parties at the start of the supervision relationship. Such a learning agreement should cover learning objectives and opportunities; how supervision should occur; a framework for giving feedback; and how strengths and weaknesses will be acknowledged.

Coaching and mentoring: questions and models

Questioning is a key skill that many psychiatrists have great ability in, but the skill of asking powerful questions can always be enhanced. A survey of useful questions is beyond the scope of this article (many examples are given in Whitmore Reference Starr2017). He lists some of his favourites as:

• What advice would you give to a friend in your situation?

• What would be most interesting to talk about first?

• What will success look like?

Other questions that I have found useful include:

• What do you sense they need from you?

• What has been different about the way you have been working with them?

• What would you do if you were in charge?

• What support do you need to do that?

Avoiding ‘why?’ questions, questions with multiple layers and leading questions is advised in many texts. Questions that are open and questions that encourage the individual to choose the next step and to think about what support they will need to take that step are often fruitful.

The models used in coaching and mentoring are useful for structuring these conversations. The GROW model, probably the best known, was originally published by Whitmore in 1992 and appears in his more recent titles (Whitmore Reference Starr2017). The acronym stands for:

-

Goal – the proposed outcome of your meeting

-

Reality – an exploration of what is happening right now

-

Options – what is currently under consideration and

-

Will – or a sense of motivation to proceed.

The following are examples of questions that might be used when applying the GROW model, from Whitmore (Reference Starr2017):

Goal questions:

• What would you like to achieve in this conversation?

• If you had a magic wand, where would you like to be at the end of this?

• It sounds like you have two goals, which would you like to focus on first?

Reality questions:

• What is happening at the moment?

• What impact is this having on you?

• Who else is involved?

Options questions:

• What could you do?

• Who could help you with this?

• What else could work here?

Will questions:

• When precisely are you going to start?

• What will you do to make sure that happens?

• What is your commitment to taking that action, on a scale of 1–10?

Many of these questions will be familiar to psychiatrists from therapeutic work with patients, for example using the magic wand (miracle) question in solution-focused therapy; scaling questions to monitor, say, levels of confidence; and posing questions to connect progress to tangible changes in behaviour or emotional management.

Considering other tools that might be used in coaching and mentoring, notwithstanding the lack of evidence, Starr (2008) highlights that personality profiling is used in coaching to increase the coach's understanding of an individual. One advantage this might have is that it allows the coachee to discuss themselves in a less self-conscious way. It might help the coach to understand what the coachee is good at, what they value and what they want to improve. Some useful objective material to work on in a coaching or mentoring relationship can be gleaned by means of 360-degree (or 360) feedback.

Coaching involves learning, and many tools have been developed to try to elicit learning styles or communication preferences. Although there is little evidence to support the questionnaire devised by Honey & Mumford (Reference Harper and Roman1982) as a valid instrument in assessing learning styles, a more recent system of learning preferences developed by Fleming in 1992 (vark-learn.com/) known as VARK, using the Visual (e.g. watching a video), Auditory (e.g. engaging in discussion), Reading/writing (e.g. making a written summary) and Kinaesthetic (e.g. participating in role-play) methods of learning has been proposed. It is now thought, somewhat more realistically, that a learning approach is student- and task-specific, that is to say that an individual will adopt one approach for one task and a different one for another (Bandaranayake Reference Bandaranayake, Dent and Harden2001).

Box 3 continues our case example with an extract from the coach's questioning of her coachee.

BOX 3 Case example: some coaching questions

I began the session with an open question: How has your week been?

He said it had been difficult, especially as the Care Quality Commission had sprung a visit on the unit.

After he had said enough about this to satisfy himself, I asked how had he got on with the goals he set himself last time: in particular, chairing the team meeting with B present. I reminded him that we had discussed this last time and he was anticipating some challenge from her.

He said that it had gone much better than he had expected. Although she did not like the plan, she appeared more thoughtful than she had been and seemed less angry.

I said that sounded encouraging. What had he done differently?

He said he had tried to talk to her in advance of the meeting and had also been speaking to her colleagues, who had told him that she was having some personal difficulty. Rehearsing the conversation with a housemate had also helped.

I asked: And so what impact did this change have on you?

He said it had made him realise that some planning had made quite a lot of difference to the meeting, and the rehearsing especially.

I asked whether that was a technique that could be useful in the future.

Who else would it be helpful to involve?

So to summarise…

Coaching supervision

The supervision in coaching and mentoring provides for continuous development of coaches and mentors. Supervision is typically provided by an experienced person and accreditation bodies require that coaches are supervised, rather as in other fields of therapy practice.

There are different models for coaching supervision, such as the double-matrix model by Hawkins & Shohet, first developed in 1989 (Hawkins Reference Hawkins and Shohet2006). It has (rather unfortunately, in my view) become known subsequently by the term ‘seven-eyed’ by other writers in the field.

This model has seven domains or areas of focus:

• the coachee and how they present

• the strategies and interventions used by the coach

• the relationship between the coachee and the coach

• the coach

• the supervisory relationship

• the supervisor's own process

• the wider organisational context.

The justification for such a model is that all aspects of the encounter that have relevance are considered. It also supports safe, ethical practice and accountability. This improves the quality of the work, can help transform the relationship with the coachee and provides a space for reflection – for the coach to become aware of their own responses to the coachee and to be able to question these and to avoid becoming ensnared by, shall we say, less than conscious material that could be problematical if not recognised. There is also a justification for it on the grounds of prevention of burnout and for giving constructive feedback and support for ongoing professional development.

Clearly, however, one disadvantage is the cost in terms of time and resources needed.

In Box 4 our coach describes an interaction with her coaching supervisor.

BOX 4 Case example: an interaction from coaching supervision

I presented to my supervisor an extract of another coaching session.

He said ‘The goals as you describe them seem very broad. Is there any way of focusing one or two? Does one influence any of the others?’

I said ‘Yes, it does seem difficult to pursue just one or two as the lists he sets himself are long. Maybe this is about his anxiety.’

He asked ‘What do you need to do to help him focus on one at a time?’

I thought for a moment and said ‘I think I will need to come back to this in the next session. The other problem I am finding is that he seems to expect me to tell him how to be a leader.’

He replied ‘Well, of course that may be a reflection of the positive relationship you have developed. However, that is not your role, which is rather to facilitate understanding and facilitate change.’

I remembered ‘He is thinking of doing a course in leadership as well.’

He said ‘It is possible then that this course fulfils the other goals in helping him learn about leadership?’

I replied ‘Yes – that's helpful. We can certainly discuss that.’

He summarised ‘Well, it sounds as if it is going well. What do you think are the best ways of keeping him focused on the priorities?’

Evaluation

The kinds of methods and sources of data capture to evaluate coaching and mentoring include hard data, which might be easier to measure and quantify, can be more easily translated into resources, can give common measures of performance and can be more credible with management if a business case is needed. Soft data may be less credible as a performance measure, but often is more interesting on a human level. Evaluation could include:

• 360 feedback

• surveys, interviews and structured questioning

• observed performance

• records of objectives or achievements

• number of coaches or mentees seen

• feedback from other staff

It is relevant to recognise that research on coaching and mentoring in all fields is still in its infancy, has many challenges and can be likened to complex health services research, in that there are many variables. Much of the research to date concerns case studies, but mixed-methods studies, drawing on triangulation between qualitative and quantitative methods, are likely to be most useful.

Indeed, Carter (Reference Carter2006) in her work Practical Methods for Evaluating Coaching, published by the Institute for Employment Studies, concludes that there should be more evaluation for coaching to gain credibility and that there has been a lack of neutrality and objectivity in evaluations generally.

At an individual level, evaluation could encapsulate any of the following:

• improved sense of support

• improvements of knowledge, skills and experience

• innovations

• enhanced performance (as measured by completed work, attendance, sickness absence, career progression)

• evidence of reflective practice (e.g. in reflective logs)

• developments in leadership expertise

• enhanced networks

• evidence of independence, autonomy and self-development

• more effective prioritisation

• achieving balance between work and personal life

• improved sense of connection with the workplace.

At an organisational level, an appealing and diagrammatic scheme can be found in a document by O'Neill (Reference O'Neill2016).

Part 2

Organisational context

The UK's National Health Service (and organisations related to it, such as Health Education England) are learning organisations and have been founded on principles of teaching and learning since their inception. Maintaining a culture in which learning is entwined with day-to-day work needs not only involvement of everyone in the organisation but also, crucially, the involvement of the executive team.

For coaching and mentoring to be established in organisations, there needs to be emphasis on support and continuous learning, so that the following can apply:

• coaching and mentoring are seen as essential skills at all levels and as a fundamental element of leadership

• learning is a priority and supported by top management

• people are encouraged to find ways of improving skills and knowledge alongside more general personal development

• people are not afraid to ask for help

• communication is open and information is shared freely

• continuous improvement is emphasised

• reflective practice is understood

• learning experiences are widely available.

The context of the coaching and mentoring and the relationships between the coach/mentor and the coachee/mentee will clearly be influenced by these wider considerations.

Organisational challenges for doctors undertaking coaching and mentoring

There are challenges in establishing coaching and mentoring in organisations such as the NHS. Some of these are structural and some ideational. Hawkins (Reference Guerrero and Brenner2012) has described the creation of a coaching culture and some of the barriers to this.

The first perhaps is the organisational support and the resources – financial and meeting space, for example – that are needed.

The second challenge is the consultant job plan. To include time for being a mentor or coach within an already full clinical timetable, including other already existing training responsibilities, would be a challenge in many clinical services.

And this relates the third point, which concerns roles. According to Clutterbuck (Reference Clutterbuck2014), failure to distinguish between the roles of line manager and mentor can lead to confusion and even conflict. This is especially so when a line manager undertakes appraisals as well.

Finally, in the chapter Problems of Mentoring Programmes and Relationships (Clutterbuck Reference Clutterbuck2014: p. 109–118) there is a description of personal and organisational factors that can go wrong in mentorship programmes, such as lack of clarity about role, too little or too much formality, power alignments, being mentored by one's line manager, failure to establish rapport in the relationship, perpetuation of narrow ways of thinking, differences in maturity and difficulties that can arise with mixed-sex mentoring relationships. This is why coaching (and mentoring) supervision can be important.

Opportunities for more coaching and mentoring

As the pressure on services grows, so the pressure on doctors and other NHS colleagues grows too. Fortunately, the calls to support staff are growing louder, and in the past year alone there have been several major documents from the General Medical Council (GMC) and Health Education England about doctors’ (and other health service colleagues’) well-being. The NHS Staff and Learners’ Mental Wellbeing Commission (Health Education England 2019) has recommended an NHS Workforce Wellbeing Guardian, a board-level role, in every NHS organisation; and the GMC document Caring for Doctors Caring for Patients (General Medical Council Reference West and Coia2019) was based on a review co-chaired by a psychiatrist. There are eight references to coaching within it and nine references to mentoring, with a call to action that the culture of the NHS must change and for the leadership to become more compassionate.

There is now work on the importance of coaching and mentoring interventions in the support of marginalised groups such as women in academic roles or international medical graduates in the context of differential attainment (a concept written about extensively by Woolf Reference Szabo, Lloyd and McKellar2011). Indeed, a useful toolkit is now available on the website of Health Education England's London and South East Deanery devised by Mendel & MacDonald-Davis (Reference Hawkins2019) to help trainers train faculty in supporting and supervising trainees from diverse cultural backgrounds using coaching and mentoring approaches.

Coaching and mentoring have important roles to play not only in mitigating against the risks of burnout, but also in offering support and professional development opportunities to doctors who wish to enter leadership roles and for those who may otherwise need additional support.

Conclusions

Although there are obstacles in current clinical practice to undertaking coaching and mentoring, there are persuasive arguments for the use of both types of support beyond the well-recognised application of mentoring for the newly appointed consultant. Coaching and mentoring can be useful at other times of role change in professional life when leadership skills need developing, but a wider availability of coaching and mentoring might also contribute to the retention of senior workforce and to the reduction of workplace exhaustion. It could contribute to the greater attractiveness of psychiatry in improving a sense of personal development, engagement and a sense of belonging.

Coaching and mentoring conversations with trainees can facilitate learning and be used to give meaningful feedback. As clinical and educational supervisors are increasingly being called on to support trainees from international backgrounds and to mitigate the effects of differential attainment, it is perhaps time to consider the adoption of these approaches more widely in psychiatric training culture and time for coaching and mentoring to become professionalised in psychiatry.

Declaration of interest

None.

An ICMJE form is in the supplementary material, available online at https://doi.org/10.1192/bja.2020.53.

MCQs

Select the single best option for each question stem

1 With respect to the GROW model of coaching and mentoring:

a the R stands for Retaining what you have been advised

b the G stands for goal

c the W can stand for what you want

d the O refers to outcomes

e the acronym was developed by Fraser in 1992.

2 Mentoring is suitable for:

a leadership development

b mediation

c when counselling is not available

d colleagues’ trainees

e inclusion in bullying policies.

3 Coaching will be undertaken by:

a anyone with a background in mentoring

b a line manager

c someone outside the organisation

d a colleague of long standing

e someone who has a background in medical psychotherapy.

4 The focus of the mentor:

a is short term

b is usually by using challenge as a strategy

c involves feedback

d does not usually include personal issues

e does not usually involve the organisation.

5 Emotional intelligence involves:

a scrupulosity

b leadership

c courtesy

d political correctness

e self-awareness.

MCQ answers

1 b 2 a 3 c 4 c 5 e

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.