A diary can provide the reader with a window into an individual’s soul. The writer’s most intimate feelings – joy, happiness, anguish and despair – become apparent by the tone of language and words employed. Each syllable is a reflection of their thoughts. But is it possible that we possess an equally powerful tool, one that enables us to portray our emotions through a different artistic form? Can a brush stroke convey the same emotion as a word? Is it possible that a painting can provide an image more vivid than a description? Edvard Munch was a Norwegian artist who not only painted his life onto canvas, but recorded it in writing. Influenced by Hans Jæger and bohemian ideologies, Munch’s ultimate goal was to keep his ‘soul’s diary’ (Reference PrideauxPrideaux 2005) – a way to explore his own psychology and feelings. Through influence from 19th-century symbolism and 20th-century German expressionism, Munch produced art that was poignant, controversial and is still widely appreciated, particularly in Western Europe.

Brief biography

Munch was born in 1863 in Ådalsbruk, Norway. His family moved to the capital, Christiana (now Oslo), where he grew up. He was an intelligent individual and excelled in his studies. Initially studying engineering at college, Munch learned about perspective and scaled drawing. However, he left college after one year, to pursue his desire to become a painter. Munch was ill during much of his early life and, before the age of 15, was forced to deal with the death of his mother and favourite sister, both from tuberculosis. Another sister was diagnosed with schizophrenia and was admitted to psychiatric hospital on several occasions. Later, his brother died from pneumonia and his grandfather died of spinal tuberculosis. These encounters with disease and death exposed Edvard to a personal fear that illness was inevitable for him too. After his father’s death in 1889 he wrote, ‘My father was temperamentally nervous and obsessively religious – to the point of psychoneurosis. From him I inherited the seeds of madness. The angels of fear, sorrow, and death stood by my side since the day I was born’ (Reference PrideauxPrideaux 2005: p. 2).

The mind expressed in art

Obviously, a person’s mental state affects their behaviour. When an individual is mentally ill, psychiatrists must make a diagnosis based on this behaviour, and treat the individual as a result. Derek Russell Davis explains that art forms are studied by writers and critics, who then interpret the message of the artist. Davis highlights the similarity this has to the way in which psychotherapists make diagnostic interpretations about illnesses of their patients (Reference DavisDavis 1981: p. 82). This suggests that painters such as Munch could be portraying a deeper message within their artwork about their mental state. Indeed, during his life and following his death, Munch has been diagnosed with depression, anxiety and bipolar disorder, among other illnesses. The ways in which figures are orchestrated, expressions are portrayed and colours are assigned present clues about Edvard’s suffering. This is similar to the way in which verbal and behavioural expressions are able to present symptoms of illness to a doctor.

Many of Munch’s early works embrace pessimistic themes. Death, anxiety and depression are all vividly exposed through his use of colours and characters.Footnote †

The Sick Child

The Sick Child (Fig. 1) is a sad freeze-frame from Edvard’s life in which he portrays the moment before his sister dies of tuberculosis in 1877. The devastating psychological effect of losing a loved one is intensely revealed in Munch’s obsession with this painting: first painted in 1885, he often returned to this image, painting it many times, until 1926. His fixation with the scene shows the deep impact this event had on his psychological state, and how it continued to affect him throughout his life. Munch described the painting as a ‘breakthrough’, writing ‘That picture […] provided the inspiration for the majority of my later works’ (Reference StangStang 1977: p. 60). Perhaps his breakthrough was his ability to express his sister’s death with pure emotion on a canvas. He describes this time of his life: ‘I could not believe that death was so inevitable, so near at hand […] Was she really going to die?’ (Reference StangStang 1977: p. 34). Although his words portray a sense of his hurt and confusion at the prospect of death, they do not fully communicate his feelings. However, it appears that Munch could paint what he could not describe.

FIG 1 The Sick Child, 1886 [Oil on canvas; 119.5 × 118.5 cm]. National Museum, Oslo, Norway/Bridgeman Images.

The Sick Child is like a page from a diary, full of emotion and sentiment. Each version that Munch painted depicts the same scene: a pale, sick child with her carer, the woman so overcome with sadness that she cannot look at the girl. The dark colours reflect the sombre mood and maybe even give a clue to Munch’s developing depression. As his breakthrough came with such a personal painting, it shows the profound effect that his psychological state, in this case depression, had on his art.

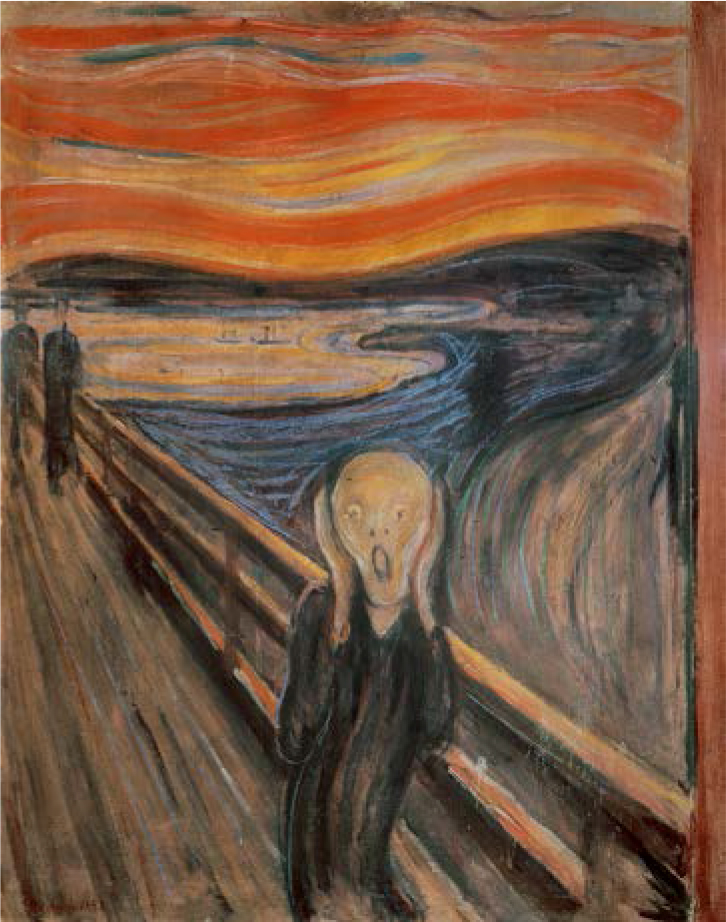

The Scream

Munch found that life had become difficult in Norway, where his art was met with minimal appreciation. He was suffering financially as well as feeling offended because his work was not receiving the credit he felt it deserved. This led him to move to Germany in 1892, where he felt more accepted. Munch’s paintings seemed to reflect the persecution he was feeling; his art moved away from the theme of death and seemed to shift towards his increasing feelings of anxiety. It is during this time and through his famous painting The Scream (Fig. 2) that this anxiety may be most evident.

FIG 2 The Scream, 1893 [Oil, tempera and pastel on cardboard; 91 × 73.5 cm]. Nasjonalgalleriet, Oslo, Norway/Bridgeman Images.

FIG 3 The Sun, 1911–1916 [Oil on canvas; 450 × 780 cm]. University of Oslo, Norway / Bridgeman Images.

The Scream is a widely recognised image, used commonly in popular culture as a symbol for fear and anxiety. At first glance, I felt that it symbolised depression. I could relate it to times of my life when I had felt hopeless and out of options. To me, the bridge represents the end of the road, with nowhere left to turn. The figures in the background represent the people in my life, at that moment just shadows around me. The central figure is almost alien-like. A unique form, it appears to be neither male nor female. The scream seems to take over the painting, distorting the figure, the sky and the water.

Munch’s reasons for painting this iconic picture were very different. It depicted an experience he had had while watching a sunset on a walk. He ‘felt as though the whole of nature was screaming’ (Reference StangStang 1977: p. 90). Munch obsessed over what he had seen, feeling anxious until it was painted. The scene itself was not one of pain, illness or suffering, but this is the way in which Munch visualised it. Gustav Schiefler recalls how Edvard explained that he had painted ‘not just a straightforward scene, as it would appear to the outside world, but a subjective image […] which always appeared in glaring colours […] whenever he closed his eyes’ (Reference StangStang 1977: p. 94). This image was not what everyone else would see; his painting was a reflection of the way his psychological state made the world appear to him. This highlights the importance of recognising that not every person or patient will view their disease, treatment or situation in the same way.

Over the years, Edvard Munch’s mental health deteriorated. In 1908, he admitted himself to Kornhaug Sanatorium, where he was treated by Dr Jacobson. Munch knew he held many psychological traumas; however, he had refused to undergo treatment for many years: ‘They are part of me and my art. They are indistinguishable from me, and it would destroy my art. I want to keep those sufferings’ (Reference StangStang 1977: p. 107). Munch recognised that the link between his psychological state and his paintings was an important one, and was reluctant to risk losing his talent.

The Sun

When Munch left the Kornhaug Sanatorium, his art seemed to have developed. Pessimistic themes were still present, but not to the same extent. Within the year, he produced a large painting entitled The Sun. The colours used are bright, and the rays of the sun seem to stretch to each corner of the painting. It exudes strength, power and optimism. This painting seems completely different from his earlier work. Edvard’s paintings were brighter and more positive than they had ever been. Just as in a diary, the expression in his paintings had changed with his mental state.

Paintings as visual diaries

Edvard Munch’s artworks provide a snapshot of his life and a glimpse into his mind. They present a lens through which we may view the world of a person who is suffering. Paintings can be visual diaries, able to reflect the extent of an individual’s psychological and even physical suffering. If Munch’s paintings were bound together in a book, they would depict his emotions more clearly than a diary ever could:

‘The notes I have made are not a diary […] they are partly extracts from my spiritual life’

‘My pictures are my diaries’

Edvard Munch.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.