Introduction

Commercial trade is a primary threat to many species of birds in Indonesia, including the laughingthrushes (Garrulax spp), which are traded as songbirds (Shepherd Reference Shepherd2010). Seven species of laughingthrush species are native to Indonesia: Sumatran Laughingthrush Garrulax bicolor, Bare-headed Laughingthrush G. calvus, Black Laughingthrush G. lugubris, Chestnut-capped Laughingthrush, G. mitratus, Sunda Laughingthrush G. palliatus, Rufous-fronted Laughingthrush G. rufifrons and Chestnut-hooded Laughingthrush G. treacheri. The Rufous-fronted Laughingthrush has been assessed as ‘Endangered’ on the IUCN Red List (BirdLife International 2013a) and the Sumatran Laughingthrush as ‘Vulnerable’ (BirdLife International 2013b) with trade being a leading threat to both species. The remaining four species are listed as ‘Least Concern’. Taxonomy and vernacular names here follow Gill and Donsker (Reference Gill and Donsker2016).

These species were found to be traded openly and in violation of Indonesian regulations (Shepherd Reference Shepherd2007). For instance, in 65 surveys carried out from 1997 to 2008 in the major bird markets in the North Sumatran provincial capital, Medan, 11,007 laughingthrushes of 10 different species, including all the native Indonesian species, were observed to be offered for sale (Shepherd Reference Shepherd2010). Furthermore, some of Indonesia’s laughingthrush species are in serious decline (Collar and van Balen Reference Collar and van Balen2013). Within Indonesia, only the Rufous-fronted Laughingthrush is listed as a protected species under the Act of the Republic of Indonesia No. 5 of 1990 concerning Conservation of Living Resources and their Ecosystems (widely known as UU No. 5 or Act No. 5), prohibiting any capture or trade of this species. Native species not on the protected list may be captured or traded only if a quota is allocated for the species. Quotas are set annually by the Directorate General of Forest Protection and Nature Conservation (PHKA) of Indonesia, however no quotas are allotted for any native species of laughingthrush and therefore any trade is deemed to violate Indonesian legislation and regulations. Protected species may be traded legally if they are captive-bred, but we know of no commercial breeding of laughingthrushes in Indonesia, which was further corroborated by traders who stated these species were taken from the wild. This study examines the extent of the trade in laughingthrushes in the bird markets of major cities on the Indonesian island of Java.

Methods

We carried out complete, one-off inventories of eight bird markets in four cities in Java in 2014 and 2015 as part of a broader full inventory of bird markets in Java conducted by TRAFFIC. These included three markets in Jakarta (Pramuka, Barito and Jatinegara) (21–23 July 2014; Chng et al. Reference Chng, Eaton, Krishnasamy, Shepherd and Nijman2015), three markets in Surabaya (Kupang, Turi and Bratang), one in Malang (Pasar Burung Malang) and one in Yogyakarta (Pasar Satwa Yogyakarta) (22–24 June 2015; Chng and Eaton Reference Chng and Eaton2016). The first three markets were selected as they are major wildlife markets in the capital city of Jakarta, and a known hub for the bird trade, while the latter were selected because of anecdotal information about birds from eastern regions of Indonesia being traded through Surabaya and because of the size and prominence of markets in these cities (Profauna 2009); all markets had between 23 and 87 stalls selling birds (Chng et al. Reference Chng, Eaton, Krishnasamy, Shepherd and Nijman2015; Chng and Eaton Reference Chng and Eaton2016). Only birds openly displayed to the public for sale were recorded and prices were asked of the dealers opportunistically. Surveyors were skilled in species identification and familiar with the Indonesian bird trade and relevant Indonesian legislation. The visits were ad hoc and the timing was based on the availability of the researchers.

The UNEP-WCMC CITES trade database was queried for records of international trade in CITES-listed species from 2000 onwards (downloaded 27 June 2015). All prices were obtained in Indonesian Rupiah (IDR) and are reported here in both IDR and US Dollars (USD) using the conversion rate of USD 1 = IDR 11,650 for July 2014 data and USD 1 = IDR 13,300 for June 2015 data.

Results

Laughingthrushes were observed for sale in all eight markets surveyed, totalling 615 individuals representing nine species (10 taxa) (Table 1). The Sunda Laughingthrush was the most numerous, with 215 individuals observed in 30 shops across seven markets. Both subspecies were observed, though only two were G. p. schistochlamys from Borneo, observed in two separate markets. The non-native Chinese Hwamei G. canorus was the second most numerous, followed by the Chestnut-capped Laughingthrush.

Table 1. Laughingthrushes observed in Indonesian bird markets – 2014-2015.

*B = Number of birds, S = Number of stalls in which the birds were found.

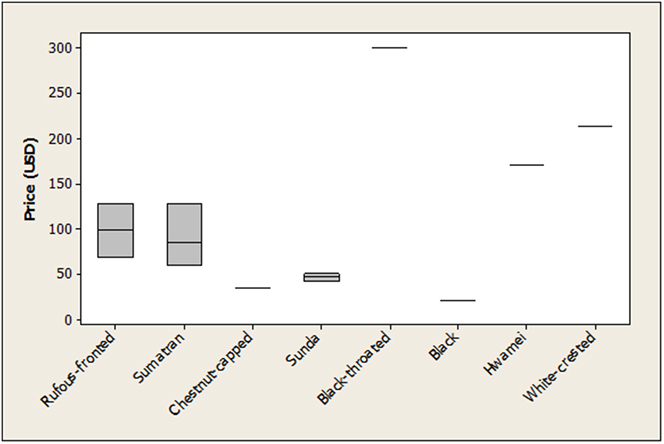

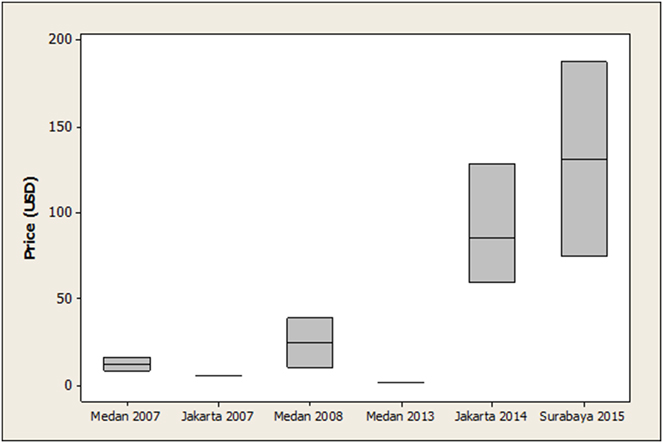

Traders were generally suspicious of outsiders in many of the markets, including the researchers, and therefore few data on prices were obtained. Nonetheless, at least one price data point was collected for almost all the laughingthrush species in Jakarta (Figure 1) and for the two threatened species in Surabaya. The non-native species were the most expensive: Black-throated Laughingthrush was the most expensive as it is particularly prized as a good singer, followed by White-crested Laughingthrush and Chinese Hwamei. The most expensive native species were the Rufous-fronted Laughingthrush (USD 69–129) and Sumatran Laughingthrush (USD 60–129), both of which are threatened. From previous studies, prices for Sumatran Laughingthrush were available also across a number of locations and years (Figure 2). Prices for Rufous-fronted Laughingthrush were available from Medan in 2008 (Shepherd Reference Shepherd2010). An individual Rufous-fronted Laughingthrush was offered for USD 45, which is less than in Jakarta in 2014 (USD 69 in Pramuka and USD 129 in Barito), and Surabaya in 2015 (USD 113 in 2015).

Figure 1. Comparison of prices of laughingthrush species in Jakarta 2014. Boxplots show the range of prices and median price, for species where more than one price was obtained.

Figure 2. Comparison of Sumatran Laughingthrush prices surveyed in different times and locations. Medan 2007 and Jakarta 2007 prices are from Shepherd (Reference Shepherd2007), Medan 2008 prices are from Shepherd (Reference Shepherd2010) and Medan 2013 prices are from Harris et al. (Reference Harris, Green, Prawiradilaga, Giam, Hikmatullah, Putra and Wilcove2015). IDR prices were converted to USD using OANDA’s historical dates for the survey months, and inflation in USD was adjusted using US Inflation Calculator.

Four of the dealers, when asked for prices, gave unsolicited information regarding the source of the birds. In all four cases, perceived exotic locations were incorrectly given as the origins, presumably to attract customer interest and justify high prices, or perhaps the sellers were genuinely not aware of the birds’ origin.

Discussion

The majority (74%) of the laughingthrushes observed were native to Indonesia, including Sumatran and Rufous-fronted Laughingthrushes, endemic to Indonesia and assessed as threatened by IUCN. One non-native species, the Chinese Hwamei, was numerous (26%), and present in most markets surveyed. Unsurprisingly, Pramuka in Jakarta had by far the highest numbers of laughingthrushes. The inventory recorded a total of 16,160 birds of all species here, far higher than any of the other markets (Chng et al. Reference Chng, Eaton, Krishnasamy, Shepherd and Nijman2015). Malang had very few laughingthrushes despite the fairly large size of the market (68 stalls). The focus of the market appeared to be on competition-class species (Chng and Eaton Reference Chng and Eaton2016), but it is unclear if the small number of laughingthrushes is typical of the market or a matter of available stock on the day itself.

Prices quoted for local researchers (Harris et al. Reference Harris, Green, Prawiradilaga, Giam, Hikmatullah, Putra and Wilcove2015) are expected to be lower than those quoted for foreigners (Shepherd Reference Shepherd2007, Shepherd Reference Shepherd2010, this study, B. van Balen in litt.), which would explain the apparent drop in Sumatran Laughingthrush prices from 2007 to 2013 in Medan (Figure 2). However, in Jakarta, where the same researcher carried out both surveys, it is clear that there has been an increase in prices, mirroring the increasing rarity of the species. Another interesting factor, though perhaps not surprising, is that the prices appear to increase as the distance from the species’ range in Sumatra increases (Chng and Eaton Reference Chng and Eaton2016).

Of particular concern are the Sumatran and Rufous-fronted Laughingthrushes. There is a paucity of recent records in the wild of Rufous-fronted Laughingthrush throughout the range of both subspecies. Since 1990, the nominate subspecies rufifrons only has records from Gunung Gede-Pangrango National Park (Collar and van Balen Reference Collar and van Balen2013, J. A. Eaton pers. obs.). The subspecies slametensis (restricted to Mount Slamet, Central Java) has not been recorded since 1925, despite a recent ornithological expedition spending seven days searching and mist-netting there (Mittermeier et al. Reference Mittermeier, Oliveros, Haryoko, Irham and Moyle2014). Only four Rufous-fronted Laughingthrush were observed during this survey, none of which were of the subspecies G. r. slametensis and it is possible that this subspecies no longer exists in the wild. Their near disappearance from local bird markets, suggests a serious decline in numbers, and we strongly recommend that the species be urgently reviewed for reassessment on the IUCN Red List.

Found throughout the montane forests of Sumatra, Sumatran Laughingthrush was previously considered conspecific with White-crested Laughingthrush (Collar Reference Collar2006, Shepherd Reference Shepherd2007). Since gaining species status (Collar Reference Collar2006), interest has grown in the species from birdwatchers and researchers. Despite this, there are very few records away from remote areas (J. A. Eaton pers. obs.), with most field observations now coming from the northernmost province of Aceh on Sumatra, which most sellers indicate as the origin of birds observed in markets (J. A. Eaton pers. obs.). Former trappers who are now birdwatching guides inside Bukit Barisan Selatan National Park indicate that although it was formerly common and easy to catch, there have been no recent records of this conspicuous and vocal species. Since 2000 we are only aware of sightings from six areas on Sumatra. It is now absent from the wild from many areas on Sumatra (J. A. Eaton pers. obs.) but are still regularly encountered in small numbers in markets throughout Sumatra (J. A. Eaton, unpubl. data). The IUCN Red List currently lists trade as the primary threat to the survival of this species, and urgent actions have been called for (Shepherd Reference Shepherd2007, Reference Shepherd2010, Reference Shepherd2013, Collar et al. Reference Collar, Gardner, Jeggo, Marcordes, Owen, Pagel, Pes, Vaidl, Wilkinson and Wirth2012). Given the lack of recent records of the species in the wild and the persistence of numbers observed in trade, we recommend the species be assessed for a potential up-listing from ‘Vulnerable’ to ‘Endangered’. The species, currently not on the list of protected species despite the threat from trade, also requires better legal protection under Indonesia’s national legislation.

Of the other species, the Spectacled Laughingthrush and Black Laughingthrush are found through Peninsular Malaysia and Sumatra, the former previously considered conspecific with Chestnut-hooded Laughingthrush, endemic to Borneo, as Chestnut-capped Laughingthrush (Collar Reference Collar2006). Sunda Laughingthrush is endemic to Sumatra and Borneo and has two races: palliatus on Sumatra and schistochlamys on Borneo. All species of Indonesian laughingthrushes are found in submontane and montane forests. Chinese Hwamei, Black-throated Laughingthrush and White-crested Laughingthrushes G. leucolophus are native to Indochina and southern China, while Buffy Laughingthrush G. berthemyi is a Chinese endemic. Due to their protected status under the quota system, all Indonesian laughingthrushes openly observed for sale in the markets had been acquired and traded outside of the laws and regulations. This indicates that enforcement of legislation and regulations designed to protect species from over-exploitation in Indonesia is lacking.

The Chinese Hwamei is the only species of laughingthrush observed during this study listed in the CITES Appendices. However, the CITES trade database shows no records of this species ever being imported into Indonesia since it was first listed in Appendix II in 2000. Therefore, all Chinese Hwamei observed during this study should be considered illegal. Dealers questioned about this species during previous studies in Medan, North Sumatra, acknowledged that Chinese Hwamei was smuggled illegally into the country, often hidden in shipments of other legally imported birds (Shepherd Reference Shepherd2010). It seems this practice continues, with 157 Chinese Hwamei observed during this current study on Java.

Bird singing competitions have long been popular on Java (Nash 1993, Jepson et al. 2011). Historically, both the Chinese Hwamei and Black-throated Laughingthrush were used in such contests (Shepherd Reference Shepherd2010), but from our recent observations, and other researchers’ (B. van Balen in litt.) they are no longer used. As both of these species were considerably more expensive than both Rufous-fronted Laughingthrush and Sumatran Laughingthrush (Figure 1) (which are not used in song contests due to their poor singing ability (B. van Balen in litt.), this could be due to the average buyer no longer being able to afford the higher prices.

Recommendations

Based on available information, and on the findings of this study, we propose upgrading the Rufous-fronted Laughingthrush from ‘Endangered’ to ‘Critically Endangered’, and the Sumatran Laughingthrush from ‘Vulnerable’ to ‘Endangered’ on the IUCN Red List and, at the time of submission, both species were undergoing a re-assessment of their threat category. We also recommend that the Sumatran Laughingthrush, a species already being targeted for trade, is listed as a protected species under Indonesian law. Authorities should be encouraged to enforce this protective legislation, and officers should be equipped to identify the species in markets. Individuals and organisations monitoring the markets should support enforcement efforts by reporting, in a timely manner, all observations of this species in trade. Enforcement agencies are encouraged to prioritise actions in bird markets where legally protected species are traded (such as Pramuka), and to take necessary action against traders selling birds which are protected and for which there is a zero harvest quota, prosecuting them with penalties severe enough to serve as a deterrent and discourage further illicit bird trade.

Beyond enforcement, we recognise the need to increase awareness amongst relevant stakeholders in Indonesia, including conservation organisations, enforcement agencies and CITES authorities, to raise the profile of the conservation needs of these species. Efforts should also be made to discourage bird keepers and hobbyists from purchasing any protected species, or species for which there is no harvest quota. The value of these species should be monitored over time to determine whether the asking prices increase with the onset of enforcement activities or a change in the status of the wild populations, and conservation measures should be adjusted accordingly. Urgent field surveys are required for Rufous-fronted Laughingthrush at historical sites on Java to search for any remaining populations, including montane areas east of Bandung for the subspecies slametensis.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Richard Thomas and three anonymous reviewers for useful comments on a previous draft of this paper. Two anonymous donors are also thanked for generously supporting our monitoring and research of the bird trade in key Southeast Asian countries.