I have been asked to speak about the life of the Empress-Queen Maria Theresa. I would like to start by directing your attention to the cover pictures of three recent biographies (Figures 1‒3). If you look at these pictures you will find one astonishing commonality. I am sure that this is neither a coincidence, nor just a fad: on each of the three covers, you only see a part of the portrait. For me, this perfectly symbolizes a specific, skeptical view of biography writing. As a biographer, these cover pictures say, you never get the whole picture of a person. It's always up to the author not only to choose the material but also to establish a certain narrative structure. A life is not a story, and a biography does not simply tell itself. There is always more than one true life story of a person. As the Swiss historian Valentin Groebner recently put it: “The past is a big untidy cellar. It is a bit damp and dark and smells a bit strange there. We go down and get what we want.”Footnote 1 What you choose and how you arrange it—which story you tell—depends on which perspective you take and in what you are interested.

Figure 1: Cover: Tim Blanning, Frederick the Great: King of Prussia (New York: Random House, 2016). Used with permission.

Figure 2: Cover: Lyndal Roper, Martin Luther: Renegade and Prophet (New York: Random House, 2016). Used with permission.

Figure 3: Cover: Barbara Stollberg-Rilinger, Maria Theresia: Die Kaiserin in ihrer Zeit (Munich: C.H. Beck, 2017). Used with permission.

In the case of a famous heroic figure like the Empress-Queen Maria Theresa, it's not just the abundance of sources you have to cope with but also the imaginations that have been entwined around this figure for more than two centuries. When dealing with Maria Theresa you are inevitably dealing with a myth. Writing her biography, I wanted to question that myth.Footnote 2

Maria Theresa was the icon of the Austrian state (or rather of several different states) of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Her image has been shaped by two impressive memorials: one is the gigantic bronze monument on Vienna's Ringstraße, erected in 1888. The other one is a written monument, the ten-volume biography by Alfred Ritter von Arneth, director of the State Archives, published between 1863 and 1879.Footnote 3 Arneth also created the program for the Ringstraße monument. While the two monuments were under construction, the Habsburg monarchy was losing its former greatness little by little. In this situation, contemplating past crises that had been heroically overcome could convey hope and a sense of orientation for the future. Both memorials to Maria Theresa, the one in bronze and the one in paper, are perfect examples of monumental history in the sense of Friedrich Nietzsche's famous second Untimely Meditation on the Use and Abuse of History (1874). History writing is “monumental,” in his terminology, if it places the past in the service of present-day hopes and expectations: “history is a means against resignation.” It teaches “that the greatness that once existed had been possible and may thus be possible again.” Monumental history in Nietzsche's sense, however, must flatten out the differences between past and present; “the individuality of the past has to be forced into a general form and all its sharp angles and lines broken to pieces.”Footnote 4 That is exactly what the classic narrative about the empress did. The two nineteenth-century monuments have shaped this narrative about Maria Theresa ever since. Nineteenth-century monumental history, however, is blocking a sober view of her.

There are some obvious reasons why Maria Theresa was the ideal object of monumental history. The classical narrative about her was like a fairy-tale plot. In short, it goes like this: once upon a time, there was a beautiful young princess who inherited an enormous empire that was in a state of ruin, and she was attacked on all sides by evil enemies. She persuaded a horde of wild but noble warriors to help her and, with their support, defended the throne of her ancestors. Three times she came up against her most perfidious opponent and fought for her most valuable province. She lost it, but her defeat became her victory, for it was only thanks to this ordeal that she managed to disempower her father's resentful old advisors and thereby join forces with clever young men to turn her ailing empire into a modern state. When, surrounded by her many children and loved by all, and even by the lowest of her subjects, she closed her eyes forever, not even her worst enemy could deny her his respect. This is how the story was told since the middle of the nineteenth century and how it is still told, for example, in the recent docudrama of the Austrian public broadcasting corporation. This story is not entirely untrue, of course, but highly selective, to say the least.

What made Maria Theresa an extraordinary source of fascination for (almost exclusively male) historians was her mixture of “masculine” heroism and “feminine” virtue. She was known not only as an empress but also as a faithful wife and mother of sixteen children. Sensational fertility combined with virile leadership, female and male perfection in a single person, made Maria Theresa an exceptional figure—even when compared with other famous female rulers of world history, like Cleopatra, Elizabeth I, or Catherine II. Whereas these other monarchs were either unmarried or childless or sexually promiscuous or all at once, Maria Theresa alone united wise governance, conjugal fidelity, impeccable morals, and teeming fecundity. She appeared, in other words, to be an exception even among exceptions.

However, as a female monarch she was the great exception that didn't question the rule—namely, that politics is a male business—but rather proved it. For a rule only properly takes shape when it is transgressed—provided that the exception remains just that. As an exceptional woman, Maria Theresa posed no threat to established gender roles. On the contrary.

For Maria Theresa, as her gentleman admirers of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries wrote, did not rule by abstract reasoning; she acted naïvely, based on her feminine intuition, with a heart better educated than her head, ever the loving, caring mother, characterized by winning goodness and a certain need for support, always letting her mind follow her heart, and so on—the quotes extolling such stereotypically feminine virtues could be multiplied at will. In a highly influential panegyric written for her two hundredth birthday in 1917 and reprinted in 1980 in a commemorative volume on the two hundredth anniversary of her death, Hugo von Hofmannsthal finally catapulted her into the sphere of the supernatural and elevated her to a mythical figure. He took the title Magna Mater Austriae literally, attributing to her a kind of political childbearing capacity: “The demonically maternal side of her was decisive. She transferred her capacity to animate a body, to bring into the world a being through whose veins flows the sensation of life and unity, onto the part of the world that had been entrusted to her.”Footnote 5 In other words: she bore the state as she bore her sixteen children, being literally “the loving mother of her lands,” as she had called herself in her famous political testament of 1750/51.Footnote 6 The process of state building appeared as parturition, the Habsburg complex of territories as an animate being that owed its life to the maternal ruler.

It goes without saying that this narrative was shaped by the classical gender dichotomy, ideally represented by Maria Theresa, on the one hand, and Frederick II of Prussia, on the other. According to this master narrative, Frederick the Great stood in relation to Maria Theresa as intellect to emotion, mind to heart, enlightenment to tradition, sterility to fertility, cold rationality to maternal warmth, and so on and so forth. Austrian culture was feminine, Prussian masculine. In short, everything fit harmoniously into the eternal antagonism of man and woman.

It is this persisting narrative of Maria Theresa that a biography today has to deal with. But, as I said in the beginning, the traditional story shaped by nineteenth-century historians is not simply wrong. And it would be naïve to believe that we could now simply tell the correct story. At best, we can tell a somewhat more distanced, more skeptical one; or, rather, we can tell different stories from different perspectives—and try to understand how the myth came about in the first place.

Here I want to deal with one element of her myth, probably the most crucial one that encompasses all the others: namely, that she loved her people more than her own children and was loved by them in turn, gladly lending an ear even to the lowest of her subjects. Alfred von Arneth, referring to Voltaire, put it this way: “The magic of her personal demeanor, the heart-winning way that she met everybody, the unrestricted access to her, the evident amount of time that she spent listening to the pleas and complaints of the lowest of her subjects and trying to give comfort and help . . . , all this won her the great admiration of everyone who came close to her.”Footnote 7

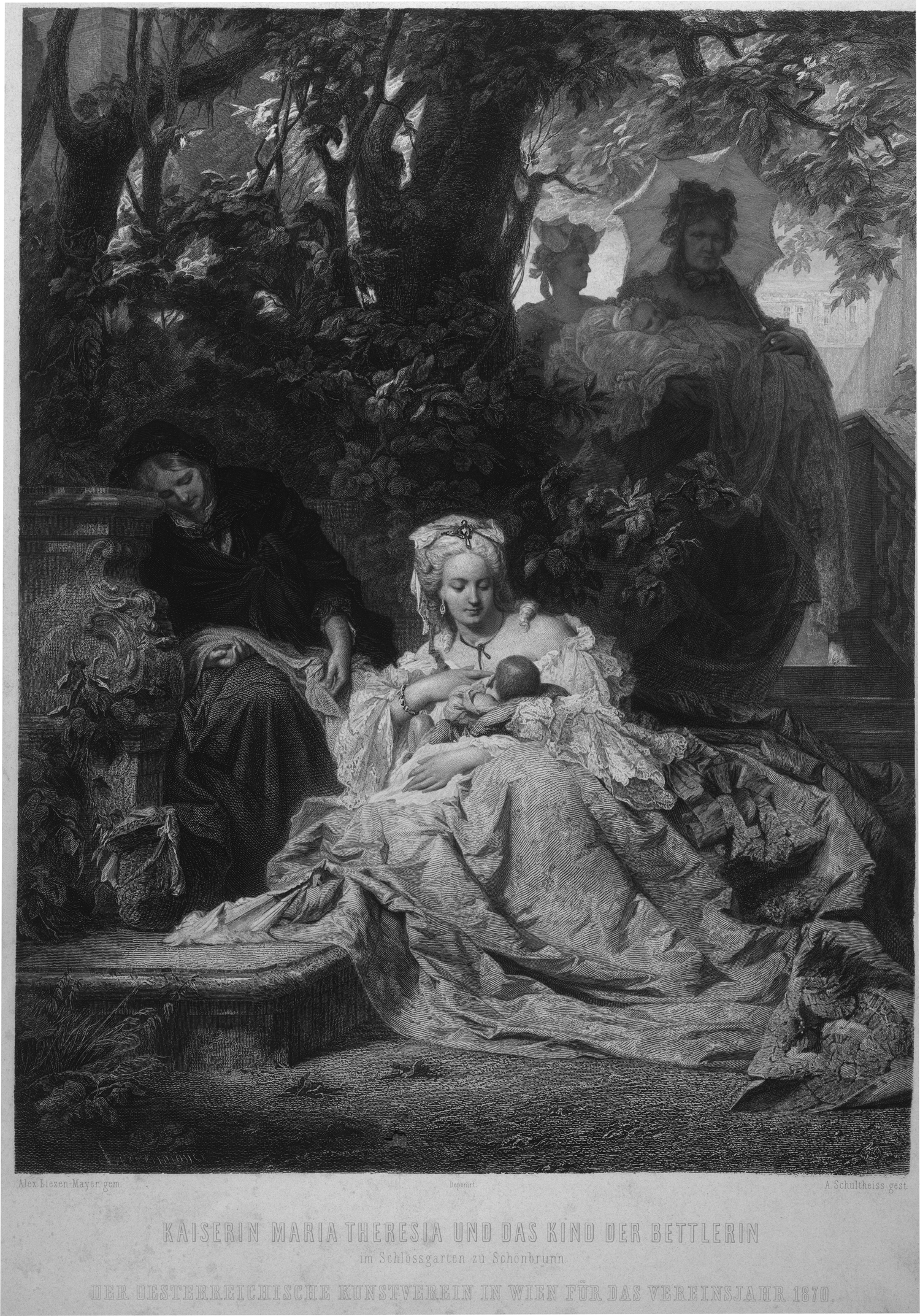

This specific combination of loving maternity and general accessibility, love of her subjects, and love of her children was perfectly reflected by a popular legend of the nineteenth century (Figure 4). Walking through the park of Schönbrunn, the legend reads, Maria Theresa came across a sleeping beggar woman with a weeping baby and did not hesitate to appease the child by personally breastfeeding it.Footnote 8 Of course, the story is a bizarre anachronism, for Maria Theresa did not even breastfeed any of her own children. It is all the more telling, though, because it takes her myth literally: being a loving mother to all her subjects, even and especially the lowest, as the model of ideal motherhood would have it in the nineteenth century. (By the way, it's equally misleading to take Maria Theresa as a role model of twenty-first-century feminism, like the very renowned French intellectual Elisabeth Badinter did in her biography of the empress, titled Le Pouvoir au féminin, meaning “Female power as such.”Footnote 9)

Figure 4: Maria Theresa breastfeeding a poor woman's baby. Copperplate by Albrecht Schultheiß after a painting by Alexander von Liezen-Mayer. In Daheim (1868). ÖNB Vienna/Bildarchiv Austria (Pk 3003, 530).

Now, the idea of the monarch being the loving father or mother of their subjects is obviously a traditional topos. Historians cannot look into the hearts and minds of the individuals to find out if they “really” loved Maria Theresa and vice versa, whatever that might mean. Nor do we have opinion polls that would have measured the ups and downs of her popularity, as we have them today. We can only analyze the emotional rhetoric of the time. And we can try to reconstruct what the actual communication between ruler and subjects was like.

So, in the following, I'm trying to answer the following questions. First, as for the alleged accessibility for even the lowest subjects: Which forms of communication existed between the empress and her subjects? When and where did they personally meet each other, and how did they behave toward each other? Further, what was the legend of love and accessibility based on in her specific case? How did Maria Theresa's charismatic reputation emerge?

The general accessibility of the empress was a topos not only in the nineteenth century but also in her own time. Listening to everyone's concerns was a very old topos, an indicator and a symbol of a good ruler. However, a closer look at the sources shows that the dictum of Maria Theresa granting access even to the lowest subjects cannot at all be taken literally. On the contrary. In fact, she restricted the rules of access to her court even more than her predecessors had done.

In general, the invisible barriers that kept common people from the court were so obvious that they hardly needed to be made explicit. Entry to the court on various occasions was governed to the smallest detail and carefully structured hierarchically by formal entry arrangements. The common people did not even appear in these regulations. When the orders spoke of “everybody” (jedermann or tout le monde), they always meant “everybody of rank” (jedermann von Stand). And, when mention was made of access for “low people”—because “low” is, of course, a relative term—what this usually meant was access for, at lowest, councilors (Geheime Räte), doctors, and other so-called half-nobles (Halbadel).Footnote 10 In 1753, Maria Theresa placed new restrictions on public audiences, even stricter than before. People could no longer be placed on the audience list unless they had obtained a signature from the Lord Chamberlain (Oberkämmerer). Maria Theresa also instilled that later among her children when they led their own courts: “it is in no way appropriate that anyone and everyone may appear in your court.”Footnote 11 She sent her children exact lists of the people to whom they should grant access, and admonished them to receive the high nobles and only them once or twice every week, with the express purpose of giving them “the opportunity to do something for their families.”Footnote 12

The “common people” were treated quite differently. Personnel at the Viennese court were instructed to “tell the guards to hold back the invasion of eager common people at court festivals and court functions.”Footnote 13 Even in great dynastic rituals, when the ruling family joined together with “the people” to stage both head and body of the realm as a ritual community, “the people” were usually represented by estates and corporations. The crowd was excluded from the palace, their ceremonial role being reduced to watching and applauding the ritual parade in the streets.

The court, however, traditionally involved common people as objects of the sovereigns’ grace—in the mode of symbolic pars pro toto. With exceptional acts of personal charity, the rulers presented themselves as loving parents of all their subjects. The most spectacular example was the traditional public washing of feet on Maundy Thursday in front of the assembled courtiers.Footnote 14 Empress and emperor would kneel to wash and kiss the feet of twelve poor old men and women, and serve them symbolically—following the example of Jesus at the Last Supper (as is still observed today, not only in the papal curia but also in the Anglican Church). However, the individual subjects were carefully selected, washed, and given new clothes to wear before the imperial couple went to serve them with golden basins and lace-trimmed linen cloths. Nothing was eaten of the food that was dished up, and it is not clear if the feet were even wetted. The whole event was an impressive staging of humility and charity as cardinal virtues of a Christian ruler, a ritual of symbolic inversion.

There was, however, another medium that people could use to be heard by the ruler, a medium that was supposed to be open to literally all subjects, namely, the supplication.Footnote 15 Subjects sought the empress's support not only with requests for favors but also with complaints, especially when they felt they were being treated unfairly by their lords or local officials. According to the traditional concept of rule, a good monarch had to provide refuge to his subjects against the injustice of lower authorities because only the monarch himself or herself was deemed to be above all partiality, committed only to the common good. Those groaning under the arbitrariness of their lord or local officials desperately wished to believe in the maternal grace of the—supposedly accessible and gentle—sovereign.

Maria Theresa, however, did all she could to discourage her subjects from taking the road to her court. She repeatedly gave commands to the intermediate authorities “to warn the subjects about the journey to Vienna.”Footnote 16 As is well known, she initiated an ambitious series of administrative reforms.Footnote 17 Subjects should always first address their complaints to their landlords, then to the newly established district office (Kreisamt), then to the new regional government (Repräsentation und Kammer), and only then to the court. But it turned out that the subjects were unwilling to go through a formal process that was long, expensive, and unpredictable, and especially so if it was the authorities that were the source of the injustice. Maria Theresa therefore ordered expressly that the lower authorities give a certificate to everyone who complained. By this, those subjects who made their way to Vienna anyway should be able to prove that they had already complained at every level of the hierarchy. However, to certify that was hardly in the interest of public officials because to do so would have meant issuing a certificate of their own failure. We are still lacking detailed research on how the subjects made use of the new administrative institutions, but it seems that the attempts to establish functioning bureaucratic procedures made it even more difficult for simple subjects to reach the ruler's ear. Paradoxically, that did not affect Maria Theresa's fabulous reputation at all—on the contrary. The more unreliably the authorities worked, the more unshakable remained the subjects’ confidence in the gracious sovereign. It was highly improbable that this confidence be subjected to a reality check. So, it was exactly her remoteness in her distant residence that protected Maria Theresa from being held personally responsible for grievances, and the bureaucratic reforms even reinforced that mechanism.

However, it happened now and then that daredevil subjects with a particularly urgent concern would lie in wait for the empress to throw themselves at her feet—on her way to a public church, for example, on one of her rides, on her promenades in the park of Schönbrunn, or at public theater performances—occasions where the boundaries between courtly and urban space were permeable. This happened when Maria Theresa had issued the order in winter 1744/45 to expel all Jews without exception (about twenty thousand persons) from the city of Prague. Numerous intercessions by even the most powerful patrons—including the pope—failed. So, one particularly bold member of the Jewish community, in his desperation, waylaid the empress in the street and begged her for mercy. It was in vain.Footnote 18 Another dramatic example is the case of a group of twelve desperate peasants’ wives from the Waldviertel trying to beg mercy for their husbands who had been imprisoned and tortured by their landlord.Footnote 19 In cases like this, the supplicants were not just rejected but sometimes also arrested and locked up either in prison or hospital—or even deported to Transylvania.Footnote 20

There was yet another significant exception to how simple subjects could gain access to the empress: as objects of amusement for the court society. In the sources, there are many stories about common people being presented at court in the mode of ridicule.Footnote 21 The most telling one is the story of Peter Prosch, a poor orphan from Tyrol who traveled around southern German courts and more or less involuntarily played the court jester at a time when this was already becoming anachronistic and was no longer in line with enlightened taste.Footnote 22 In his autobiography Prosch described his success at the Viennese court as a parody of the classic courtly career. In this narrative, Maria Theresa plays the role of a fairy queen appearing to the poor boy in a dream that comes true in the end. He, the lowest of all subjects, gets access to the court, where the gentle empress treats him like her own son, and he meets her in a mode of social reciprocity. The crucial point is that the jester could allow himself to meet the ruler on eye level because it was precisely by doing so that he proved himself a jester.

To sum up, it's beyond doubt that Maria Theresa sought to keep any direct contact with supplicants from the common people at bay as far as possible. People from the lower ranks could only appear legitimately at court in three different roles: as lowermost servants, as recipients of symbolic charity pars pro toto, or as objects of amusement. This being said, the questions are: How could that myth of Maria Theresa's general accessibility emerge, and what made it so resistant against empirical falsification? On what was Maria Theresa's charisma based?

A German pamphlet of 1745 (when the war of Austrian succession seemed to draw to a close) was titled “Why Is the Queen of Hungary [Maria Theresa] So Extraordinarily Loved?” The anonymous author attributed this to her being a woman and a mother, more precisely, an exceptionally beautiful young woman. “The excitement of affects is the greatest art in a state, whereby kings can preserve everything. . . . A woman has the advantage over a man that her deeds make a greater impression in the mind. There is a more tender inclination against the beautiful sex.” Nature makes it easier for female rulers “by their beauty and pleasing” to win the minds of their subjects and to find obedience.Footnote 23

Thus, the contemporaries—and even more so the later historians—attributed it to Maria Theresa's youth, beauty, and femininity that she succeeded in winning the military help of the Hungarian nobles in the War of Austrian Succession through her personal address to the Hungarian Diet in 1741. There she appeared as the embodiment of persecuted virtue, rightful royalty, and beauty. Later this story was retold, painted, and printed innumerable times—including the latest docudrama on Austrian television. The helpless young mother defeats the wild Hungarian warriors with her beauty and provokes their chivalrousness, so that they come to her aid and save her empire. Thus, the picture stages a paradox: the power of female weakness. The scene did not take place in the way it was depicted, however. The presence of the little heir to the throne transforms the painting into a picture of the Madonna, identifying the earthly queen with the Queen of Heaven, the patron saint of Austria.

Almost everyone who set eyes on Maria Theresa in the first years of her reign, not just her admirers, remarked on her personal charm. The English ambassador, for example, wrote in 1753, “Her person was made to wear a crown and her mind to give luster to it. Her countenance is filled with sense, spirit, and sweetness, and all her motions accompanied with grace and dignity.”Footnote 24 Even in 1755, when she had already given birth to thirteen children and had put on considerable weight, the Prussian envoy Fürst noted, “The empress is one of the most beautiful princesses in Europe. . . . She has a majestic yet friendly gaze. . . . One does not approach her without a deep sense of admiration.”Footnote 25 Descriptions of her beauty and charm had an almost topical character; it seemed to be a sign of her monarchical dignity and legitimacy, an attribute of her role.

Personal charisma is something that is not just aired by the charismatic person but also attributed to her by others; both sides—the objective and the subjective—are inextricably linked. To understand how Maria Theresa's charisma worked, it is helpful to have a closer look at records from visitors to Vienna who met her in person. Many of them were members of the “middle ranks,” such as the Mozarts for example, who did not belong to the aristocratic court society but recommended themselves to the ruler by exceptional works of art, literature, or scholarship.Footnote 26 The public audiences that Maria Theresa granted people of their sort were highly valuable precisely because they always remained extraordinary favors. The route to the imperial audience followed an effective strategy of ceremonial escalation. Everything was designed to produce ambivalent feelings: with every threshold the visitors crossed, they felt more impressed and intimidated, and yet more honored to have been personally chosen. Once they had gone through the long and complicated ceremonial procedures, they were surprised by the personal kindness of the empress.

Usually Maria Theresa showed her visitors as many of her children as possible because they were the living guarantees of dynastic continuity. Everyone had to pay their formal respects to all the children and to kiss their hands, thereby paying demonstrative homage to the dynastic principle. That was a ceremonial innovation that met with no small resistance of foreign ambassadors. Visitors of lower rank, though, misinterpreted the empress's displaying of her children as a sign of familial intimacy. Those who had expected solemn formality in the court's innermost center were surprised and enthusiastic. They felt personally singled out, and almost inevitably became firm admirers of the empress. There is no doubt that Maria Theresa mastered the art of charming people to an extraordinary extent, and she did so consciously and strategically, as numerous letters to her children show.

The more difficult it was to gain admittance to her, the greater was the effect of her charm on those who had made it—and the stronger was their desire to let the whole world participate in this experience. Many visitors of middle rank not only carried the empress's praise to the world but also and especially increased their own renown. This is where the exploding book market and the increasing public sphere come into play. Because many of these visitors had access to print media, the personal charisma of the empress became widely known, and this effect, then, took on a dynamic of its own.

Those who had access to the empress could hope to enjoy all possible benefits. The Viennese court was based, like all courts, on the fact that all kinds of goods, both material and symbolic, were handed out there, and Maria Theresa certainly handed out plenty of both—always, note well, on the basis of personal favor, generosity, and voluntariness, not on the basis of general and abstract legal claims. No one had a formal right to the sovereign's favors; people could also leave with nothing. Maria Theresa doubtlessly mastered the art of distributing graces; she managed to keep expectations alive and to hold disappointments controllable. Those who were favored by Maria Theresa carried her praise out into the world. Those who were not could still hope, and therefore did not want to forfeit their chance through public criticism.

The vast majority of subjects, who couldn't hope to ever meet the empress-queen in person, did encounter her in ever new variations in countless depictions.Footnote 27 Maria Theresa was probably the most portrayed ruler of her time. She was the subject of around a hundred large-format state portraits, in addition to an untold number of copperplate engravings, miniatures, coins, and medallions. The different genres of portrait served different ends and were tailored to different audiences. There were the great conventional state portraits from the court painter's studio, showing the sovereign resplendent in her jewelry and royal insignia. Putting rulership on display, these images had a representative function in the full sense of the word: they represented the absent sovereign in governmental chambers or courtrooms and, as such, had to be treated with the same deference as if she were there in person. Miniature copies of such portraits were applied to tobacco boxes or rings in various degrees of preciousness. Beyond the court milieu, images of the empress were available for simple subjects as well: on fans, tiles, tableware, and copperplates for the better off, on coins for everyone (Figure 5). It was not unusual for even peasants to have a portrait of the queen before their eyes on the wall or on their drinking vessels: “The picture of the Queen of Hungary is honored everywhere,” a contemporary wrote.Footnote 28 The court strategically pursued this politics of images, even arranging for portraits of the imperial family to be produced and sold to the public. The explicit intention was to stimulate feeling of love among subjects “since arousing emotions is the greatest art in a state by which kings can obtain everything.”Footnote 29

Figure 5: Copperplate of imperial family by Johann Michael Probst (after 1756). ÖNB Vienna/Bildarchiv Austria (PORT_00067346_01).

It is beyond question that the topos of Maria Theresa's universal accessibility to the lowest of subjects is a myth. Her court was just as socially exclusive as the other major European courts, if not more. In spite of this, her reputation was already legendary among her contemporaries. To explain this, it is not enough to point at her personal qualities but also the particular constellation and the communicative structures of the time. Common people tended to project their hopes and dreams onto Maria Theresa because she was a woman and a mother, complying (at least in her youth) with all contemporary standards of beauty and virtue, and because she resisted the superiority of her enemies against all expectations. This constellation was the basis of her almost magical reputation.

This especially worked with the simple subjects far away in the distant territories, without any direct access to the court. The fact that Maria Theresa restricted the opportunity for subjects to present their concerns, paradoxically, even strengthened her general reputation as a universally accessible, impartial, and loving mother of the people, an earthly Magna Mater Austriae. The more distant she was and the more otherworldly she appeared, a genuine fairy-tale queen, the less she would disappoint expectations.

In the capital, however, things looked different. After the empress's death in 1780, public reactions in Vienna were much more ambivalent than the court had expected. In his memoirs, Duke Albert of Saxony, her son-in-law, described the shock felt by all those who had known the empress personally. But the common people, “le populace,” as he called them, greeted the funeral procession with “scandalous indifference” (which he attributed to the fact that they had been angered by the recently introduced beverage tax).Footnote 30 If her death marked for some the end of an epoch, for others it was the dawning of a new era. The journalist Johann Pezzl, for example, declared the year of her death to be the “year of salvation, the boundary marker of the enlightened philosophical century.”Footnote 31 In the revolutionary period around 1800, an English observer reported that the fame of Maria Theresa had completely faded. Instead, it was her son Joseph II who became the hero of reformers and revolutionaries. They now condemned what Maria Theresa had been praised for. Sovereign generosity was now regarded as redistribution from the poor to the rich; personal access to the monarch now appeared as superfluous, if not harmful and suspicious of corruption.

Perceptions changed again, fundamentally and lastingly, in the second half of the nineteenth century. When the new Austro-Hungarian Dual Monarchy was established in 1867, it was Maria Theresa who was celebrated as the real ancestor of this peculiar new state. But this constitutional monarchy no longer was comprised of subjects, but citizens. This is the reason why Maria Theresa was retrospectively depicted in anticourtly, antiaristocratic colors. Her myth underwent reinvention. She was made into a bourgeois housewife, a citizen queen. It is high time to disenchant this myth.