Introduction

The authors of this research are university professors from Spain interested in improving the teaching-learning process of Environmental Education, both from educational innovation and from research. We have been aware of the potential of the use of humour in environmental education, specifically for future teachers, but before applying it to our teaching practice, we wanted to know educators’ accounts of what they perceived to be effective pedagogical uses of humour in Environmental Education.

International studies have shown the benefits of using humour in Environmental Education (Boykoff & Osnes, Reference Boykoff and Osnes2019; Osnes, Boykoff & Chandler Reference Osnes, Boykoff and Chandler2019; Russell, Chandler & Dillon Reference Russell, Chandler and Dillon2023; Topkaya & Dogan, Reference Topkaya and Dogan2020). In the Spanish context, although some educational experiences have been published (Aparicio, Marrero & Camacho Reference Aparicio, Marrero and Camacho2019; López-Rico, Reference López-Rico2019), there is a lack of research on the potentialities and limitations of the use of humour.

Therefore, this paper shows an exploratory analysis of the use of humour in Environmental Education, from the perspective of renowned Spanish specialists in Environmental Education and environmental educators with experience in a wide range of contexts, both formal and non-formal.

This paper has two specific objectives:

-

A. To identify potentialities, limitations, uses and good practices of the use of humour in Environmental Education from the point of view of university experts, according to their experience in teaching and research in Environmental Education.

-

B. To identify potentialities, limitations, uses and good practices of the use of humour in Environmental Education from the point of view of environmental educators, based on their experience in educational practice.

To achieve these objectives, the following five research questions must be answered:

-

1. What are the most appropriate uses of humour according to the participants in the study?

-

2. What are the reasons that lead the education specialists to use humour in environmental education?

-

3. What current uses of humour in Environmental Education are identified by participants?

-

4. What are the environmental issues addressed through humour according to the knowledge and/or experience of the people involved in the research?

-

5. What recommendations and good practices on the use of humour in environmental education are included in the opinions of the participants in the study?

Literature review

Humour is an innate quality of being human that it is pursued and valued in our social relationships. Although it is a difficult concept to define, we can be aware of its presence or absence (Goldstein, 1972). Humour involves the communication of multiple and incongruous meanings that are somehow amusing (Martin, Reference Martin2007). Booth-Butterfield and Booth-Butterfield (Reference Booth-Butterfield and Booth-Butterfield1991) defined humour as the intentional use of both verbal and non-verbal communication behaviours that elicit positive responses such as laughter and joy. But beyond amusement, humour can have other functions. In the following paragraphs, the uses of humour in education will be examined.

Banas et al. (Reference Banas, Dunbar, Rodriguez and Liu2011) argue that the vast majority of research on the use of humour in education has focused on its positive consequences in the classroom, particularly in terms of how it increases motivation and learning. Thus, humour has psychological and physiological benefits, promotes memory and comprehension and can increase students’ emotional engagement with the task or subject at hand, as well as making it more interesting and less boring (Sambrani et al., Reference Sambrani, Mani, Almeida and Jakubovski2014). In addition, it helps to deal with stressful situations that also occur in the teaching-learning process, especially when working on controversial topics (Osnes et al., Reference Osnes, Boykoff and Chandler2019). It also allows for closer cultural and emotional ties between students and teachers, reflecting the educators’ ability to bring the topics closer to the students, and can serve to remove social barriers and generate a sense of group feeling (Booth-Butterfield et al., Reference Booth-Butterfield, Booth-Butterfield and Wanzer2007; Hoad et al., 2018). In short, humorous content achieves better results in a learning paradigm than non-humorous material (Garner, Reference Garner2006; Sambrani et al., Reference Sambrani, Mani, Almeida and Jakubovski2014).

Humour attempts to enhance education through creative approaches and to make messages more palatable to the audience without undermining their seriousness. It can balance highly critical and unsettling messages with elements of joy and hope. Therefore, humour has been used in activism against war, environmental degradation, sexism (Branagan, Reference Branagan2007; Roy, Reference Roy2007) and racism (Cole, Reference Cole2012; Jones & McGloin, Reference Jones and McGloin2016; Rossing, Reference Rossing2016).

However, some research has found that certain types of educational humour can also have negative consequences (Osnes et al., Reference Osnes, Boykoff and Chandler2019). In addition, methodological and conceptual discrepancies in educational humour research have hindered clear conclusions about how humour works inside the classroom (Banas et al., Reference Banas, Dunbar, Rodriguez and Liu2011; Garner, Reference Garner2006).

In terms of environmental education, in recent years it has been argued that dystopian accounts of climate change are pedagogically counter-productive (Kaltenbacher & Drews, Reference Kaltenbacher and Drews2020; Topalsis, Plaka & Skanavis Reference Topalsis, Plaka and Skanavis2018), comedy and humour are increasingly seen as potentially useful means to raise awareness about climate change (Anderson & Becker, Reference Anderson and Becker2018; Boykoff & Osnes, Reference Boykoff and Osnes2019; Carroll-Monteil, Reference Carroll-Monteil2023; Nabi et al, Reference Nabi, Gustafson and Jensen2018). Young (Reference Young2008) clarifies that, in people less interested in climate change, it is likely that humour activates and reinforces belief in and perception of risk to the issue more than deeper, more intellectually demanding and thoughtful approaches. Similarly, emotions such as fear or shock may generate concern but not develop active engagement with climate change, even leading to denial and disconnection from the problem (Topalsis et al., Reference Topalsis, Plaka and Skanavis2018).

In this regard, several studies consider that the educational use of humour, understood in its diverse typology, from the most innocent (Osnes et al., Reference Osnes, Boykoff and Chandler2019) to the most satirical or sarcastic (Anderson & Becker, Reference Anderson and Becker2018; Jones & McGloin, Reference Jones and McGloin2016; Skurka et al, Reference Skurka, Niederdeppe and Nabi2019), favours engagement (Sambrani et al., Reference Sambrani, Mani, Almeida and Jakubovski2014) and critical awareness (Mora, Weaver & Lindo Reference Mora, Weaver and Lindo2015), and promotes action (Verlie, 2018). Regarding the future use of irony as an educational tool, Bengtsson and Lysgaard (Reference Bengtsson and Lysgaard2023) suggest refraining from sarcasm, and to engage with irony that comes close to what one appreciates, rather than resorting to a group or social beliefs with which one and others might not identify, which can easily lead to resentment. Lowan-Trudeau proposes several possible opportunities arising from the introduction of an “absurdist perspective in environmental education research and practice in areas such as relationships between human and non-human animals; exploring sociopolitical tensions and dynamics; environmental activism; critical considerations related to gender and sexuality; performance and creative praxis” (Reference Lowan-Trudeau2023, p.655).

Beyond the types of humour, there are also different multimedia formats that relate environmental informal education and humour, such as comedic framings in television comedies (Carter, Reference Carter2023), internet memes (Tammi & Rautio, Reference Tammi and Rautio2023), humorous serious games (Cook et al., Reference Cook, Ecker, Trecek-King, Schade, Jeffers-Tracy, Fessmann, Kim, Kinkead, Orr, Vraga, Roberts and McDowell2023) and cartoons (Gough & Horacek, Reference Gough and Horacek2023).

Humour is thus presented as an antidote to despair, promoting critical thinking and favouring nuances in interpretations rather than uncritical thinking (Boykoff & Osness, Reference Boykoff and Osnes2019). Moreover, its benefits are not limited to the field of thought but promote engagement (Sambrani et al., Reference Sambrani, Mani, Almeida and Jakubovski2014) by encouraging an active role in the resolution of everyday problems, as indicated by different initiatives in which there have been positive social changes due to the use of humour (Chattoo & Feldman, Reference Chattoo and Feldman2017). Therefore, humour can help students work on emotionally charged issues, foster critical thinking and creativity, and empower transformative learning to promote action for change (Spörk, Findler & Vogel-Pöschl Reference Spörk, Martinuzzi, Findler and Vogel-Pöschl2023). Furthermore, humour can create safe spaces that normalise the participation of instructors and students in nature education programmes in order to prioritise inclusive practices (Arias, Reference Arias2023).In Spain, there is a large literature on the role played by humour in education (Aparicio et al., Reference Aparicio, Marrero and Camacho2019; Fernández-Solís, Reference Fernández-Solís2013). Also, in specific fields such as mathematics (Aparicio et al., Reference Aparicio, Marrero and Camacho2019) and science, as in the monographic issue 60 of Alambique (Oñorbe, Reference Oñorbe2009), a journal dedicated to disseminating proposals for educational innovation, focused on the teaching of science with humour.

However, even though Environmental Education has a significant development in the country, there are hardly any contributions that address its relationship with environmental teaching and learning. Among the few examples is Escudero and Cid (Reference Escudero Cid and Cid Manzano2012) and Escudero et al (Reference Escudero, Escudero, Dapía and Cid2013), who worked on scientific literacy in the environment. On the contrary, several examples of interventions linking Environmental Education and humour have been found, most of them focusing on graphic humour; within this genre, climate change is the dominant theme. Two recent proposals can be cited: El Cambio Climático no tiene gracia [Climate Change is not funny], an exhibition of graphic humour that featured fifteen cartoonists from around the world, organised in 2018 by The Ministry for Ecological Transition and Demographic Challenge of the Government of Spain, and ¡Houston, tenéis un problema! [Houston, you have a problem!] (López Rico, Reference López-Rico2019), which includes more than a hundred environmental cartoons. Besides, with the intention of raising awareness, the Government of Spain promoted the work Medio Ambiente con humor [Environment with humour], a publication that brings together the contributions of the most outstanding Spanish comedians.

Methods

To make a first approach to the use of humour in Environmental Education in Spain, a qualitative methodology was used based on semi-structured interviews with specialists in the field and a focus group with environmental educators.

Sample

This research is based on a purposive sample whose aim was to obtain meaningful information to meet the objectives (Table 1). Five professors from different Spanish universities (Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Universidad de Córdoba, Universidad de Málaga, Universidad de Valencia and Universidad de Jaén) with a consolidated track record in environmental education were chosen to be interviewed as experts. They teach environmental education subjects in both bachelor’s and master’s degrees and have been researching and working for years in this field, with proven quality publications. These specialists were selected because of their proven experience in environmental education, even though they belong to different disciplines, in a way that they could offer complementary and enriching approaches. In the case of the focus group the purpose was to contrast ideas between participants from formal and non-formal education backgrounds. For this purpose, five people with a long educational career in this field, both in formal and non-formal settings, were selected (Table 1). This group size is manageable to establish a deep discussion on the topics and at the same time ensure the diversity of education perspectives.

Table 1. Profiles of the participants in this research

To identify them throughout this research and to differentiate the interviewees from the focus group participants, we have opted to name the participants according to the research instrument used. Accordingly, the university specialists will be called Interviewees (1, 2, 3, 4 and 5) and the environmental educators, Participants (1, 2, 3, 4 and 5). Among the selected persons, four are men and four are women.

Data collection

A reflective interview was conducted with the specialists to explore their opinions in depth, as qualitative interviewing does not seek to produce statistical evidence but provides deep insights in individual sense-making processes (Kvale, Reference Kvale2008). In the case of the educators, a focus group was held to get closer to the practice, to the implementation of experiences; in this latter case, a space was created for the exchange of ideas between professionals who did not know each other beforehand.

The bibliographic analysis of the literature made it possible to identify the key concepts of the theoretical framework which, in turn, shaped the questions used in both instruments (Maxwell, Reference Maxwell2008). The first draft with possible questions was prepared and discussed among the working group based on the literature gathered and then reviewed by a statistical consultant throughout three working meetings. The design of these questions responds to the specific objectives and research inquiries outlined above. The questions used were the same in both the interviews and the focus group, except for the first one, which asked about research in the university academic environment and was not asked in the focus group with the environmental educators.

The interviews were conducted virtually using the Cisco Webex videoconferencing application, which also allowed them to be recorded, and lasted approximately one hour. For the focus group, which lasted 90 minutes, the same tool was used. Both instruments were developed in June 2021.

Data analysis

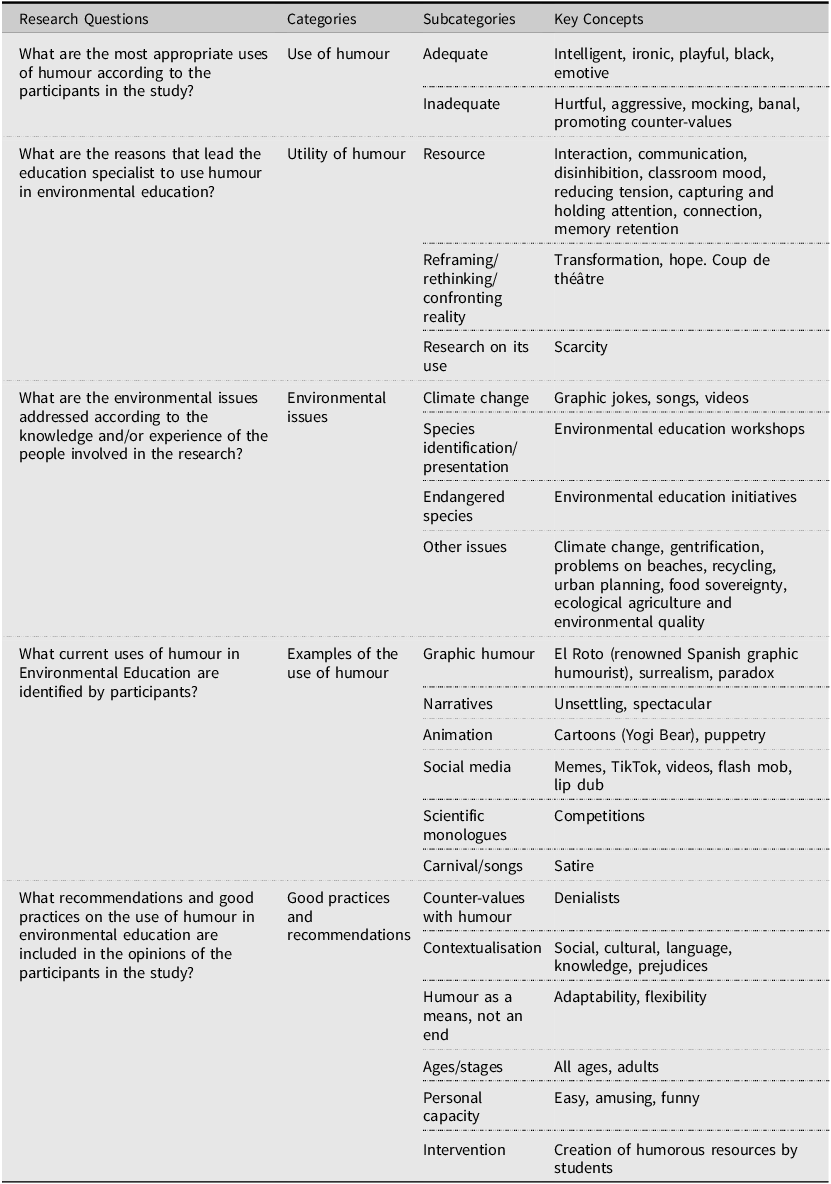

To proceed with the data analysis, an examination of the interviews and the focus group was carried out. To do so, we have followed the analysis methodology proposed by Rabiee (Reference Rabiee2004), which entails applying Krueger’s (Reference Krueger1994) method and incorporating some key steps of the method outlined by Ritchie and Spencer (Reference Ritchie, Spencer, Bryman and Burgess1994), whose stages of data analysis are: familiarisation, identifying a thematic framework, indexing, charting, mapping and interpretation. The eight criteria established by Rabiee to analyse information were taken into account: Words, Context, Internal consistency, Frequency, Intensity of comments, Specificity of responses, Extensiveness and Big picture (Rabiee, Reference Rabiee2004). This has resulted in the categories, subcategories and key concepts (Table 2) that will be described in the following section.

Table 2. Categorisation of results

Table 2 shows the main categories of the study, ranging from the appropriateness of the use of humour, the environmental issues addressed or likely to be addressed, examples of uses of humour, and good practices and recommendations. This table, which in addition to the categories presents the subcategories and the key concepts associated with each of them, allows to articulate the results found in this study. Given the significant background and diversity of the participants, these results reflect the potential use of humour for environmental education from a Spanish perspective.

The suitability of the use of humour

Although with some nuances, university specialists support the use of humour for Environmental Education; actually, they consider it important. The most appropriate genre is the so-called intelligent humour, as well as ironic, playful, black humour, and, in short, the one capable of generating emotions. In contrast, experts advise against the educational use of humour that is hurtful or aggressive, trivialises issues, or promotes environmental counter-values.

On a more concrete level, one participant commented that the most effective humour would be black humour, regarding the consequences we can expect in a few years if we do not change the present course. To do so, this person would focus on one theme, the climate emergency, using certain formats, such as graphic jokes, songs, or a ‘collapse survival kit’, as P5 suggests.

Although the use of humour is generally appreciated, some limitations are also established and all participants indicate a possible risk: the fact that humour usually empties the environmental message, which is why they opt for the use of intelligent humour. As an example, P1 alludes to a Brazilian awareness-raising campaign on the proper use of toilet flushes, which emphasised clever humorous provocation.

I3 and I4 insist on not trivialising the messages, on not making them less serious. However, the use of humour is considered very important, because environmental problems are traumatic and addressing them in this way has been shown to be unsuccessful, as I3 and P3 point out. The same argument is used to recommend a more playful approach to environmental problems, which is more useful, as “it allows for a less catastrophic approach, leading to restorative experiences” (I2). Therefore, the answers to this first question confirm that humour is a suitable resource for environmental education.

Motivations for the use of humour

When addressing the motivations that lead specialists to implement the use of humour in environmental education, its function as a resource stands out. There is an agreement in considering it as such, as it facilitates interaction and communication in the educational process. The improvement of communication and interlocution with the public, both in formal and non-formal environments, is the main reason for its use.

Among the motives that incline participants to use humour, we can highlight its consideration as a pedagogical tool to disinhibit learners while helping to create a good atmosphere in the context in which it is used, as P3 comments. They consider that, in general, humour facilitates the classroom climate, helping to relax and reduce moments of tension that can occur in environmental education. This is because, when dealing with serious and worrying issues, there is a fear that can lead to “eco-anxiety and even paralysis” (P5). P2 indicates that the positive atmosphere created by humour makes it a resource that can be very useful, favouring transforming environments and visualising, without minimising the problems, the most hopeful part of environmental education. And P2 continues in this sense: “It’s just that the format depends on what kind of educational action we want to develop: a campaign with posters, videos, advertisements… or an activity in class, or a work group in a participatory process… I lean towards the use of images (memes or similar), songs and spontaneous jokes or humour while explanations are being given, activities are being explained, or discussions are taking place…” (P2).

In line with the above, humour could be defined as an appeal to intelligence, as it encourages a “friendly and original approach to rethinking things” (P1) and “deconstruct ideas” (I5). Thus, another important motivation for the use of humour is the questioning and reappraisal of reality, “challenging stereotypes and representations” (I4). I5 mentions that humour helps to position oneself and to reconsider the world in which we live by developing the critical thought. For example, through irony, our behaviour can be highlighted, so that humour “acts as a ‘mirror’ in which we can reflect ourselves” (I2). In this sense, I2 and I3 consider that humour makes it possible to satirise bad behaviour, but to de-dramatise, not to condemn. It allows to seek enriching scenarios that raise awareness and help to make environmental issues more familiar and even provoke emotions, something that motivates learning (I3). Humour can be an engaging formula, but in no case, as mentioned above, should a superficial or unserious conception of humour be implied (I2). It also increases students’ attention, allowing for a better connection between topics, and makes information more memorable (I2).

I1 and P1 also opt for a distressing use of humour, not just funny. However, P4 remarks that it is important to be careful about what kind of humour is used, as it can lead to confusion or misinterpretation. Thus, it is recommended to be very respectful of personal perceptions when dealing humorously with a subject, as we can turn something pleasant into the exact opposite. Sometimes, depending on the target audience, one should avoid being too direct in order not to feel the use of humour as an aggression, so the limitations lie in the way it is used: “Black humour, of which I am a fan, must be handled with care, but I don’t think it should be off-limits. I’ve seen very good memes about tsunamis that are unlikely to offend sensitivities, except, of course, for those who may have experienced it firsthand” (P3).

As for the research on the use of humour in environmental education, its scarcity can be explained by the fact that humour has been approached more at the level of intervention than research, as I1 points out, although the five university specialists, who belong to different disciplines, agree on the need for research on the use of humour in environmental education, a binomial on which they warn that very little research has been carried out in Spain.

The topics addressed

The participants indicate that there is no subject in which the use of humour is more recommended than in others and they agree that humour is a tool that facilitates the approach to any environmental issue. More than the topics, the clue is “to find a proper resource” (I5).

Overall, climate change is one of the most recurrent, though others such as gentrification, problems on beaches, recycling, urban planning, food sovereignty, ecological agriculture and environmental quality also appear as examples mentioned by participants. These issues can be addressed with humour as long as it is appropriate and a means rather than an end. However, the general perception in the group is that any resource or theme can be interpreted with humour, provided there is flexibility to adapt to the context and the recipients of the message.

In general, through their interventions, the specialists reflect on the limitations of addressing complex and relevant issues without producing discourses that foster humiliation or loss of dignity. In the case of young children, for example, one should avoid being “too punctilious in specific details, as the child may confuse facts, making this approach to knowledge through humour useless” (P4). From a strictly pedagogical point of view, it is necessary to select the topics well, “as an excess of humour or exaggerations can limit the authority of the teacher” (P3). Regarding cultural differences in dealing with humour, P2 points out that the importance lies not so much in the difference between societies or countries but in the relationship between North and South and the antithesis of the contexts on a global level. For this reason, humour must take into account the use of adaptable codes that objectively reflect these contrasting realities in order to be understood. In this sense, I3 consideres it more appropriate to speak of individualistic cultures as opposed to collectivistic ones, when it comes to identifying a common humour rather than territorial boundaries.

Examples of uses of humour

The university experts participating in this study have a long research and teaching experience in environmental education. They confirm the scarcity of analytical work on this subject, something that was also concluded in the theoretical framework of this research. However, they did introduce experiences observed or developed by themselves in the course of their careers that use humour to raise environmental awareness.

Graphic humour appears most often in the discourse of the participants. I1 and I5 suggest graphic jokes as a resource that enables the development of reflective strategies. They all agree in pointing to the cartoons of El Roto, published in a national newspaper, as a good practice of this type of graphic humour, which it would be interesting to recover.

The use of humour by some environmental educators is part of the narrative approach. That is, with both children and adults, they use humour as a strategy to attract and maintain attention (I1). Although some consider that their use is more helpful at adult ages (I2) or with adolescents (I4), puppets are present in the discourses of the observed examples, and the need to use different types of communicative tools, such as social networks or digital resources (TikTok, videos, flash mob, among others), is highlighted. Monologues are also examples of good practice, especially those focused on scientific issues, scientific monologue competitions, or the use of thematic characters such as Yogi Bear, or other campaigns based on endangered animals, which generate environmental awareness through humour.

P1 offers another case of great interest, the Guided walks programme of the CENEAM in which the impact of the Spanish Civil War on the landscape of the Sierra de Guadarrama was assessed, showing the elements and consequences of the war on the environment from an analytical but informal point of view.

In the case of Spain, carnivals, and especially Andalusian carnivals, which through songs focus many of their performances on the humorous denunciation of environmental problems, as I1 remarks, stand out as resources in non-formal contexts in which the aim is also to raise environmental awareness.

Recommendations and good practices in the use of humour in environmental education

Among the difficulties faced by environmental science is the proliferation of denialists, who are not very representative in the scientific arena but are very present in the media, where they are echoed by the press. Therefore, they are part of the social representation. Humour could be a very useful tool to highlight such contradictions but “being careful not to convey counter-values” (I1) and maintaining an environmentally friendly discourse.

Humour requires a connection between sender and receiver which, in its culmination, is bidirectional, as it involves the participation of all those present in the process, as P5 indicates. There is no humour without it, and for that to be possible, there has to be a kind of connection that comes from sharing a series of elements such as language, knowledge, experiences, even prejudices and stereotypes, and others.

Humour can allow for a caricature of what should not be done but also of what is done well, “seeking an image of a world that is becoming more and more attractive” (I3). The experts’ conception of humour is always as a means and not as an end, that is, as a facilitating tool. Good practice would be that which avoids trivialisation, “which does not focus on humour, but which does use it occasionally” (I2).

Another important recommendation is contextualisation. P3 suggests that humour must be socially and culturally contextualised so that is understood and does not generate differences or be offensive, therefore educators must always consider the group and the context in which they are working.

Concerning the use of humour, the majority defends its suitability regardless of the age of the people. Although several participants highlight that it can be used with very different audiences, it is considered more suitable for adults and more difficult to use with large groups of children, though it can be channelled for each age group. Thus, if humour is used intelligently, it would be accessible to all audiences, which means knowing how to use it according to the contexts and applying different resources (P1). An opinion that differs from the other members of the focus group is the need to target environmental education, and therefore resources, that use humour on adult audiences, “as we can wait for children or young people to become adults before they do things differently” (P5).

On the other hand, specialists do not consider that there are significant differences between formal and non-formal spheres. In any case, its use is more common in non-formal educational contexts and there is even reluctance among teachers to use it for fear of losing discipline or a climate of respect in the classroom, as P3 mentions.

An example of the good uses mentioned by specialists is resorting to comic strips or surprising narratives. In these, the knowledge to be conveyed is explained in a paradoxical or surreal, intriguing, or spectacular way, using any of the many resources of humour to attract attention and produce a memory advantage. The importance of the personality of the educator also emerges in the discussions: someone’s flair for humour, their ability to create a relaxed atmosphere through jokes or comments along these lines. Thus, a lesson learned is that “a good use of humour is one that is focused both on the topic being addressed and on creating a good climate with the participants in the activity” (P4).

Finally, a relevant aspect that has been mentioned is that humour in environmental education should not be understood only as a didactic resource to be used but as a product to be generated, as part of the creative process of the group. Several people gave examples of activities to create a video or a lip dub. Related to this is the prominent role of social media and current digital tools in the use of humour for environmental education, especially with young people.

Discussion

In light of the results obtained from the analysis of the interviews and the focus group, the experts consulted are in favour of the use of humour in environmental education, in line with previous studies that have already shown the benefits of this approach (Banas et al., Reference Banas, Dunbar, Rodriguez and Liu2011; Hoad et al., 2013; Russell et al., Reference Russell, Chandler and Dillon2023; Sambrani et al., Reference Sambrani, Mani, Almeida and Jakubovski2014; Topkaya & Dogan, Reference Topkaya and Dogan2020). This is a different approach to avoid the catastrophism and polarisation that often guide environmental education actions, as Brossard notes (Anderson & Becker, Reference Anderson and Becker2018). General opinion has been more in favour of using humour that is neither aggressive nor uncomfortable (Banas et al., Reference Banas, Dunbar, Rodriguez and Liu2011; Topalsis et al., Reference Topalsis, Plaka and Skanavis2018). In fact, some experts pointed out that the use of aggressive humour is considered counterproductive because it can even impede action, agreeing withBore and Raid (Reference Bore and Reid2014) and Samson and Gross (Reference Samson and Gross2012). None of the specialists has clearly positioned themselves in favour of uncomfortable or sarcastic humour, as advocated, among others, by Anderson and Becker (Reference Anderson and Becker2018), Jones and McGloin (Reference Jones and McGloin2016), Skurk et al. (Reference Skurka, Niederdeppe and Nabi2019) or Bengtsson and Lysgaard (Reference Bengtsson and Lysgaard2023). Our findings resonate with theirs on the importance of irony.

Among the motivations for the use of humour in environmental education, coinciding with Bore and Reid (Reference Bore and Reid2014), its ability to help manage feelings of fear, helplessness and guilt about the environmental situation has been identified, which instead of predisposing and encouraging actions to change the situation can block and prevent them. As Zillmann et al. (Reference Zillmann, Williams, Bryant, Boynton and Wolf1980) concluded once, humour is suitable to capture and maintain attention, which makes it a very useful resource in the classroom. Along with these motivations, some of the specialists indicate that humour helps to confront reality, something in which they agree with Mora et al. (Reference Mora, Weaver and Lindo2015) and Keeling (Reference Keeling2020). Although the experts cite climate change as the most common topic, “it is currently unclear whether using humour in environmental communication is doing more harm than good” (Kaltenbacher & Drews, Reference Kaltenbacher and Drews2020, p. 2).

Some participants have indicated, in line with Osnes et al. (Reference Osnes, Boykoff and Chandler2019), that resources should not be overloaded with excessive environmental messaging because they could overwhelm and lose their sense of humour. Graphic humour is, in general, a resource with a long tradition in Spain (Martín, Reference Martín2005). Therefore, as has been pointed out, it is not surprising that the scarce research found on the use of humour for Environmental Education in the Spanish context or language is focused precisely on graphic humour (Aparicio et al., Reference Aparicio, Marrero and Camacho2019; Escudero et al., Reference Escudero, Escudero, Dapía and Cid2013; Hollman, Reference Hollman2012; Suárez-Romero & Ortega-Pérez, Reference Suárez-Romero and Ortega-Pérez2015). Similarly, scientific monologues and comedy shows were among the examples cited by the experts, coinciding in their assessments with the results of studies such as Skurka et al. (Reference Skurka, Niederdeppe and Nabi2019) and Young (Reference Young2008), respectively. Other examples mentioned, with international scientific evidence, are the use of cartoons (Cole, Reference Cole2012; Gough & Horacek, Reference Gough and Horacek2023) –— especially for children — and comics — for teenagers and adult audiences (Topkaya & Dogan, Reference Topkaya and Dogan2020). However, emphasis was placed on the potential to generate such products rather than on the mere use of existing materials, encouraging the creation of environmental humour by students (Spörk et al., Reference Spörk, Martinuzzi, Findler and Vogel-Pöschl2023), especially through memes (Tammi & Rautio, Reference Tammi and Rautio2023) and other visual digital content for social media, as noted by Anderson and Becker (Reference Anderson and Becker2018). Finally, according to Teslow (Reference Teslow1995), styles of humour are culture-dependent, and Morain already pointed out in the same decade that knowledge of a culture was essential to understand its humour (Sambrani et al., Reference Sambrani, Mani, Almeida and Jakubovski2014). Although there is consensus in highlighting the importance of the sociocultural context, both in the content of humour and in what can be considered funny, as shown in previous research (Banas et al., Reference Banas, Dunbar, Rodriguez and Liu2011; Guegan-Fisher, Reference Guegan-Fisher1975; Jiang et al., Reference Jiang, Li and Hou2019; Schermer et al., Reference Schermer, Rogoza, Kwiatkowska, Kowalski, Aquino, Ardi and Bolló2019; Ziv, Reference Ziv1989), it cannot be concluded that there is such a thing as a ‘Spanish humour’. However, examples of typically Spanish humour have been shown, such as the carnival chirigotas, which sometimes have environmental content. From social to individual point of view, the statements collected in this study highlight the educator’s personality, what Booth-Butterfield and Booth-Butterfield (Reference Booth-Butterfield and Booth-Butterfield1991) call ‘Humor Orientation’ and the teaching experience, with inexperienced educators being less likely to use them (Banas et al., Reference Banas, Dunbar, Rodriguez and Liu2011).

Conclusions

Once the results have been compared with the existing international literature, we have been able to meet the proposed objectives in terms of the identification of possibilities, limitations, uses and good practices from the point of view university experts and educators of Spain, where there are not many studies on the use of humour in Environmental Education. Because of this, we can therefore consider this to be a fresh contribution in Spain but considering the main international trends. However, specific features of Spanish folklore, such as chirigotas, were also mentioned by three of the eight participants, which could open up a new line of research. In this sense, it would be of interest to expand the research with other cultural manifestations related to humour, rooted in society and that are popular, as is the case of the chirigotas in Spain. Together with other local examples, this line of work would allow to know if they can be considered a useful resource for environmental education, given the potential they have in non-formal contexts and to reach the entire population. Another possible line of research in the future is to approach the students’ assessment of the use of humour to work on environmental problems, especially if a didactic intervention of this type is carried out.

In general, when we analyse the use of humour in environmental education in Spain, we can conclude that there is still a lot of ground to be covered. Based on the results of this research, the picture that emerges is very complex in terms of how to deal humorously with controversial scientific issues such as natural disasters, climate change, or cultural differences, among others. However, the beneficial influence of humour in education is recognised as a trigger for an environment conducive to participation and positive emotional engagement, creating a sense of connection between teachers and students and helping to facilitate the environmental learning experience. Of particular interest is the participants’ proposal to involve students in the creation of environmental humour to subsequently evaluate the influence of these practices on their environmental awareness.

Humour can also be an excellent tool or resource that facilitates teaching by challenging established environmental archetypes, as well as encouraging cognitive development to help set limits on their humorous comments: belittling other cultures, non-valuing of equality, or derogatory remarks to provoke laughter.

This contribution should be a point of departure, as well as a future commitment to further research into the possibilities of using humour in environmental education in Spain or in other contexts where this line of research is not yet consolidated.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all the people who have made this research possible by participating altruistically, showing interest, availability and honesty in their interventions.

Financial support

The publication of this article has been funded by the project “Transfer of innovation and research results in Science Didactics and Environmental Education for Sustainability” (PPIT2023_1_001) approved in the 1st Call of 2023 for Own Innovation and Transfer Projects of the University of Córdoba (Spain), in which J. Alcántara-Manzanares is the main researcher.

Ethical standard

Nothing to note.

Author biographies

Jorge Alcántara-Manzanares is a professor in the Didactics of Experimental Sciences Area of the Department of Specific Didactics of the University of Córdoba. His main line of current research focuses on the identification of the personal and social determinants of environmental awareness for the improvement of environmental education for sustainability in the different stages of life. In addition to the evaluation of educational programs and interventions for sustainability, research on science education with a gender perspective, and the educational importance of approaching nature. Using quantitative and qualitative methodologies.

Silvia Medina Quintana is PhD in History specialised on Women and Gender studies. She is currently professor at the Faculty of Education and Psychology of the University of Córdoba, where she teaches subjects related to the teaching- learning process of Social Sciences. Her lines of research include the gender perspective in the educational field, addressing topics such as sustainability, heritage and history.

Roberto García-Morís is a lecturer in Social Sciences Education in the Faculty of Education at the University of A Coruña (Galicia, Spain), where he teaches courses in teacher training for early childhood, primary and secondary education. He holds a PhD in History from the University of Oviedo (Spain), and his most recent work focuses on teaching and learning in social studies, geography and history based on controversial social issues and education for citizenship.

Miguel Jesús López Serrano is a professor in the area of Social Sciences Education of the Department of Specific Didactics of the University of Córdoba. Over the last few years, I have held teaching positions at different universities such as the International University of La Rioja (UNIR), the Real Centro Universitario Escorial “María Cristina” (UCM). His main line of current research focuses on the didactics of the local history of the city of Córdoba and in the narratives applied to teachers in training.