The number of children with disabilities globally is estimated at almost 240 million (UNICEF, 2021). These children have unique needs, often face additional barriers, and experience limited access to quality education (Banks et al., Reference Banks, Hunt, Kalua, Nindi, Zuurmond and Shakespeare2022; Wodon & Alasuutari, Reference Wodon and Alasuutari2018). A study analysis of 8,900 children from across 30 countries concluded that children with disabilities are 10 times less likely to attend school than their peers without disabilities (Kuper et al., Reference Kuper, Saran, White, Adona, de la Cruz, Kumar, Tetali, Tolin, Muthuvel and Wapling2018). Exclusion from education has negative implications throughout the lives of these children, contributing to more significant risks of poorer health, limited economic opportunities and poverty (Banks et al., Reference Banks, Kuper and Polack2017; UNESCO, 2010).

There is ample evidence pointing to the positive educational benefits for children from parental involvement and their collaboration with schools and educational processes (Caño et al., Reference Caño, Cape, Cardosa, Miot and Pitogo2016; Đurišić & Bunijevac, Reference Đurišić and Bunijevac2017; Goldman & Burke, Reference Goldman and Burke2017; Hussain, Reference Hussain2019; Jeynes, Reference Jeynes2007; Kimaro & Machumu, Reference Kimaro and Machumu2015; Oranga et al., Reference Oranga, Obuba, Sore and Boinett2022; Stacer & Perrucci, Reference Stacer and Perrucci2013; Yulianti et al., Reference Yulianti, Denessen and Droop2018). Parental involvement can be understood in the context of Epstein’s theory of overlapping spheres of influence, primarily linking school, family and community partnerships with students’ social, cognitive, emotional and educational development (Epstein, Reference Epstein2018). The framework outlines six types of parental involvement, framed within practice and partnership levels of parenting, communicating, volunteering, learning at home, decision-making, and collaborating with the community (Epstein, Reference Epstein2018; Kimaro & Machumu, Reference Kimaro and Machumu2015). How parental involvement is implemented, across the six Epstein types, varies, based on context and a range of personal and social determinant factors, including socio-economic, employment and income status (Wondim et al., Reference Wondim, Asrat Getahun and Golga2021).

Parental involvement is considered a strong predictor of children’s success in school, and given the widespread barriers to education they face, may be particularly important for children with disabilities (Ainscow & César, Reference Ainscow and César2006; Banks & Zuurmond, Reference Banks and Zuurmond2015; Fan & Chen, Reference Fan and Chen2001). In recent years, the involvement of parents of children with disabilities has become more prominent and recognised as an essential ingredient for the effective practice of inclusive education (Gedfie & Negassa, Reference Gedfie and Negassa2018; Goldman & Burke, Reference Goldman and Burke2017; Jigyel et al., Reference Jigyel, Miller, Mavropoulou and Berman2019; Wondim et al., Reference Wondim, Asrat Getahun and Golga2021).

Families often play a crucial role as a source of emotional, social and psychosocial support of children with disabilities (Butler et al., Reference Butler, Quigg, Bates, Jones, Ashworth, Gowland and Jones2022). The experience of parenting a child with disabilities can bring challenges, particularly if inclusive practices and support measures are lacking (Mipanga, Reference Mipanga2022; Wang, Reference Wang2008). However, research on their involvement in their children’s education is relatively scarce, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs; Wondim et al., Reference Wondim, Asrat Getahun and Golga2021). The limited research available highlights that a range of factors can influence the extent and nature of parental involvement for parents of children with disabilities, including attitudes and understandings around disability and the parental role in education, time/competing demands (Erdener, Reference Erdener2014; Hoover-Dempsey et al., Reference Hoover-Dempsey, Walker, Sandler, Whetsel, Green, Wilkins and Closson2005; Kim, Reference Kim2009; Wright, Reference Wright2009), as well as wider socio-economic, environmental, attitudinal and structural determinants (Hornby & Lafaele, Reference Hornby and Lafaele2011; Kim, Reference Kim2009; Murray et al., Reference Murray, Finigan-Carr, Jones, Copeland-Linder, Haynie and Cheng2014). Each parent and child will have unique needs and experiences. Understanding how best to promote parental involvement for parents of children with disabilities is important, given the positive impact it may have on the children’s learning and psychosocial wellbeing (Bariroh, Reference Bariroh2018; Kimaro & Machumu, Reference Kimaro and Machumu2015).

Despite the wide recognition of its importance, evidence on how best to achieve effective parental involvement in the education of children with disabilities is lacking. We found one systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness of parent involvement in special education, which identified substantial evidence gaps in this area. However, the review focused on USA-based studies only (Goldman & Burke, Reference Goldman and Burke2017). A rapid evidence assessment of what works to improve educational outcomes for children with disabilities found no intervention studies promoting parent involvement in LMIC settings (Kuper et al., Reference Kuper, Saran, White, Adona, de la Cruz, Kumar, Tetali, Tolin, Muthuvel and Wapling2018). To the best of our knowledge, outside of high-income countries, especially the USA, research on interventions to promote parental involvement for parents of children with disabilities has not been systematically reviewed.

The lack of evidence on the effectiveness of interventions for parents of children with disabilities is of concern. It is especially significant to consider the evidence gaps in different settings, including in LMICs, considering likely contextual and cultural variations in factors influencing parental involvement, such as those related to parenting beliefs and caregiving approaches (Bizzego et al., Reference Bizzego, Lim, Schiavon, Setoh, Gabrieli, Dimitriou and Esposito2020). Similarly, there is a need to understand the outcomes and outcome measures that are available to assess parental involvement interventions.

In the current systematic review, we aimed to systematically map and synthesise literature on interventions that promote the involvement of parents of school-aged children with disabilities in education. Specifically, the research questions guiding the literature review were as follows:

-

1. What interventions supporting parental involvement in the education of children with disabilities have been evaluated?

-

2. What outcome measures and assessment approaches were used to evaluate these interventions?

-

3. What is the evidence of the effectiveness of the interventions?

Methods

The current study followed the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines for a systematic review (Moher et al., Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009). The inclusion/criteria and analysis methods were specified in a protocol registered with PROSPERO in September 2020, and searches were completed in April 2021 (CRD42020191267).

Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria

The population, intervention, comparison, outcome and study design (PICOS) framework was used to formulate the eligibility criteria for the review. The study focused on peer-reviewed, primary intervention studies published in English between 2000 and 2021. Eligible studies were expected to have implemented an education-focused intervention or program for individuals or groups involving at least one parent of a child with a disability. The age range for school children was specified as 6–18 years, in line with UNESCO’s official age range for primary and secondary school levels (UNESCO, 2009). In addition, in this review we recognised the significance of school, family and community partnerships (Epstein & Sheldon, Reference Epstein and Sheldon2022) and considered home, community and school interventions (Stacer & Perrucci, Reference Stacer and Perrucci2013). The word ‘parent’ was used to include biological mothers, fathers, grandparents or other guardians responsible for children with disabilities (Wang, Reference Wang2008). Primary research included quantitative, qualitative, and mixed-method studies, with or without a control/comparison group. No restrictions were imposed on geographical settings, such as rural or urban. This was to address the potential absence of studies that would meet all criteria for inclusion in this systematic review. However, non-intervention studies or secondary analyses, reviews, reports, opinion pieces, meta-analyses, editorials, conference papers, dissertations, and study protocols were excluded from the review. Grey literature was excluded because it is often ‘not bound by the same publishing conventions that characterize white literature and comes in a variety of forms [, which pose] challenges for data management, extraction and synthesis’ (Adams et al., Reference Adams, Smart and Huff2017, p. 434).

Search Strategy

Searches were conducted across nine electronic databases: BASE, CINAHL Plus with Full Text, Embase, ERIC, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Scopus, Social Policy and Practice, and Web of Science. The search strategy included subject headings for each database (e.g., MeSH in MEDLINE) and a combination of controlled vocabulary. The key search terms were (parent* or caregiver* or famil*) AND (involve* or engage* or support groups) AND (child* or learner* with a disability* OR disabled child*) AND (school* OR education OR classroom). We chose the period 2000 to 2021 to regulate the review’s scope and at the same time capture the growing interest in parent-focused interventions for children with disabilities. The search strategy was adapted for each data source (see Supplementary Material 2). Titles and abstracts retrieved from the electronic search were downloaded into EndNote’s reference management database. Reference lists from all the articles undergoing full-text review were manually searched to identify additional articles. Retrieved articles were imported into Covidence, and duplicate references were removed. The papers, including eligible full texts, were independently screened by at least two reviewers. Conflicting views were resolved through discussion with a third reviewer.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

Data were extracted from publication details, study design and characteristics, intervention descriptions, reported outcomes, results, and conclusions. Data analysis and synthesis were done using narrative analysis, and findings were presented as recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins & Green, Reference Higgins and Green2008). A narrative synthesis was chosen considering this systematic review’s wide range of interventions (Schwarz et al., Reference Schwarz, Hoffmann, Schwarz, Kamolz, Brunner and Sendlhofer2019). In addition, pooling data and meta-analyses was not feasible due to the high methodological diversity and heterogeneity among the included studies.

Quality of Studies

The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool’s (MMAT; Version 18) methodological quality criteria for evaluating empirical studies across different study designs — quantitative, qualitative, and mixed methods (Hong et al., Reference Hong, Pluye, Fàbregues, Bartlett, Boardman, Cargo, Dagenais, Gagnon, Griffiths, Nicolau, O’Cathain, Rousseau and Vedel2018; Pace et al., Reference Pace, Pluye, Bartlett, Macaulay, Salsberg, Jagosh and Seller2012) — was used to evaluate consistency and quality of each of the 21 articles included in this review. Two reviewers independently assessed the studies, and divergences were resolved through consensus or discussion with a third reviewer. Two additional reviewers examined 10 articles to ensure consistency and objectivity in the appraisals. Each study was rated as having a high, medium, or low risk of bias. Results on the risk of bias showed mixed quality (see Table 2). Although most studies were considered weak or posed a high risk of bias, the findings were invaluable as they added to our understanding of intervention research in this area.

Results

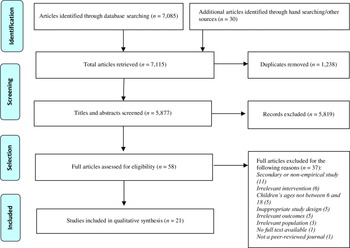

The initial electronic database search yielded 7,085 records. Our hand search through article references generated an additional 30 articles. After removing 1,238 duplicates, 5,877 titles and abstracts were reviewed for eligibility. From these, 58 full papers were evaluated, of which 21 met our criteria and were included in this review (see Figure 1, PRISMA flowchart, for details).

Figure 1. PRISMA Flow Diagram of the Review Process.

Study Characteristics

The design characteristics for each study are shown in Table 1. Most studies were conducted in high-income countries, especially the USA (n = 11). Fifteen articles involved interventions with parents of children with intellectual disabilities. The MMAT was used to categorise the study designs as quantitative descriptive, qualitative, quantitative non-randomised controlled trials, mixed methods or quantitative randomised controlled trial.

Table 1. Characteristics of Included Studies

Note. RCT = randomised controlled trial.

Table 2. Description of Study Designs, Control Group, Time Points, Sample Sizes and Risk of Bias

Note. RCT = randomised controlled trial.

All 21 interventions involved parents as primary target groups. Thirteen studies incorporated school staff, community members, health staff and civil society workers (Burke, Reference Burke2013; Burke et al., Reference Burke, Rios, Lopez, Garcia and Magaña2018; Carter et al., Reference Carter, Swedeen, Walter and Moss2012; Floyd & Vernon-Dotson, Reference Floyd and Vernon-Dotson2009; Goldman & Burke, Reference Goldman and Burke2017; Gortmaker et al., Reference Gortmaker, Daly, McCurdy, Persampieri and Hergenrader2007; Hampshire et al., Reference Hampshire, Butera and Bellini2016; Kurani et al., Reference Kurani, Nerurka, Miranda, Jawadwala and Prabhulkar2009; Kutash et al., Reference Kutash, Duchnowski, Sumi, Rudo and Harris2002; Lendrum et al., Reference Lendrum, Barlow and Humphrey2015; Mortier et al., Reference Mortier, Hunt, Desimpel and Van Hove2009; Norwich et al., Reference Norwich, Griffiths and Burden2005; Panerai et al., Reference Panerai, Zingale, Trubia, Finocchiaro, Zuccarello, Ferri and Elia2009).

The sample sizes of parents involved in the study ranged from 4 to 104 participants. Seven articles stated the number or proportion of female parents recruited in their samples — that is, an average of 85% female. Four studies involved only female parents, and no males took part.

The Methodological Quality of the Studies

Using MMAT for quality assessments, five articles had a low risk of bias, and five had a medium risk. The remaining 11 were evaluated to have a substantial risk of bias. The primary sources of bias included a lack of methodological adequacy to address the research questions (n = 3); lack of coherence between data sources, collection, analysis, and interpretation (n = 3); articles not adequately deriving findings from the data (n = 3); weak or not well-described sampling strategies (n = 3); or a lack of representativeness in the target population (n = 4). In addition, most papers did not describe the non-response and rationale for their sampling and methodology. Four articles were based on specific theoretical frameworks used to inform the development of the reported interventions (Buelow, Reference Buelow2007; Mautone et al., Reference Mautone, Lefler and Power2011; Norwich et al., Reference Norwich, Griffiths and Burden2005; Wang, Reference Wang2008). The theoretical models were the ‘parent partnership model’, ‘attachment theory’, ‘social learning/ecological systems’, and ‘knowledge attitudes behaviour’.

Intervention Descriptions

The intervention outcomes in selected articles addressed various groups of people, such as parents, children, schools and communities (see Table 3). The interventions were classified under Epstein’s six types of parent involvement framework (Epstein, Reference Epstein2018). Nine interventions supported communication between parents and school (e.g., parent training or other school support activities). Five interventions promoted learning at home through information provided to help learners with homework. Three interventions engaged parents in school decision-making. These activities were tailored to help parents and families advocate for children with disabilities and other families. In two articles, the interventions promoted parental collaborations with the community, for example, through conversations and other actions that brought together parents, schools and the community. The remaining two articles focused on parenting interventions to help parents establish supportive home environments. None of the studies focused on parents’ volunteering-related activities. The intervention formats adopted were face to face for parent support groups (n = 12) or individual families (n = 3). Thirteen studies reported the geographical settings of the interventions, with nine from urban settings, three in both urban and rural, and one in rural settings.

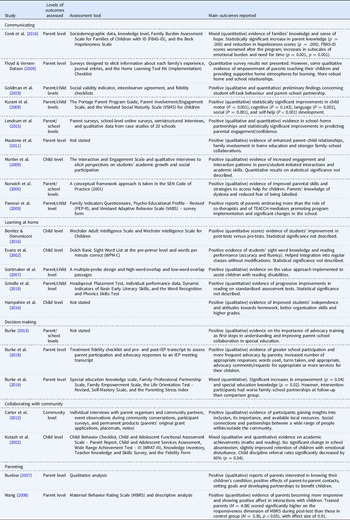

Table 3. Description of Intervention Formats, Focus and Duration

Outcome Measures and Assessment Tools

The authors of the articles included in the study used a variety of approaches and assessment tools to evaluate outcomes. The effects of the parent involvement interventions were assessed under one or more outcome categories: parent-, child-, school-, and community-level outcomes. Fifteen articles reported parent-level outcomes, and 10 reported child-level outcomes. To determine whether and what interventions were effective, results were categorised based on the reported outcomes in each article — that is, positive, mixed or no effect. All the interventions reported positive results except for three that reported mixed outcomes (see Table 4).

Table 4. Study Assessment Tools and Outcomes Reported

Discussion

The stimulus for this review was the need to identify and review interventions to promote parents’ involvement of school-aged children with disabilities in education. In our search, 21 interventions were identified, mostly from high-income countries. Only one study was from a low-income country, despite the high number of children with disabilities in those countries.

The different parent involvement interventions were categorised according to Epstein’s six types of parent involvement. Most studies focused on improving parent/school communication and learning at home. Most studies found evidence of a positive impact of the interventions, highlighting the significant contribution of parent involvement in fostering children’s academic achievements and social-emotional development (El Nokali et al., Reference El Nokali, Bachman and Votruba-Drzal2010; Epstein & Sheldon, Reference Epstein and Sheldon2002).

The study findings substantiate references to the importance of both informal (e.g., support groups) and formal (e.g., home-based, group or individualised parent education) ways of involving parents in schooling (Sudit, Reference Sudit2018). Strategies that promote home–school communications and interactions were also common in the studies in this review. Parent-peer groups can support parents in addressing their children’s needs and improving their skills to help their children with disabilities (Machalicek et al., Reference Machalicek, Lang and Raulston2015).

Notwithstanding the positive examples of parent involvement interventions in the education of children with disabilities, this review also shows several research limitations. For instance, there is a limited representation of parents of children with disabilities other than intellectual disabilities in the literature. In addition, we found substantial heterogeneity in the study designs and outcome measures of the included articles. Historical inconsistency in measuring parent involvement and equivocal findings across the articles have been highlighted in previous studies (Fantuzzo et al., Reference Fantuzzo, McWayne, Perry and Childs2004).

Most articles were characterised by a medium or high risk of bias, and only one study was a randomised controlled trial. Only five out of the 21 articles were considered as having a low risk of bias. Sample sizes were small. Up to nine studies specified sample sizes of fewer than 10 parents involved in their research. The rationale for sample sizes was not consistently reported across the studies. Since parental involvement was measured differently across studies and without control or comparison groups, it is unclear whether reported outcomes resulted from robust interventions, variations in measurement procedures, sampling differences or other factors. This highlights a need for more intervention studies to strengthen the current evidence on parent involvement.

The scarcity of intervention studies focused on parents of children with disabilities from LMICs, where most children with disabilities live, is of concern (Smythe et al., Reference Smythe, Almasri, Moreno Angarita, Berman, Kraus de Camargo, Hadders-Algra, Lynch, Samms-Vaughan and Olusanya2022). Most literature reports on interventions implemented in high-income countries, which often lack applicability in LMICs, especially in rural settings (Spier et al., Reference Spier, Britto, Pigott, Roehlkapartain, McCarthy, Kidron, Song, Scales, Wagner, Lane and Glover2016). This raises the urgency and need for paying attention to issues of context and culture during the development, testing and implementation of these interventions (Baumann et al., Reference Baumann, Mejia, Lachman, Parra-Cardona, López-Zerón, Amador Buenabad, Vargas Contreras and Domenech Rodríguez2019).

Seeing the positive effects of parent involvement interventions, replicable models supported by rigorous study designs across settings should be encouraged. That said, studies should also aim to provide information on the theoretical underpinnings of their interventions and communication on the intervention development processes. The demand for theoretically informed interventions is growing (Craig et al., Reference Craig, Dieppe, Macintyre, Michie, Nazareth and Petticrew2008). Systematic approaches with a strong rationale for the design and detailed reporting of the intervention development during implementation interventions are recommended (French et al., Reference French, Green, O’Connor, McKenzie, Francis, Michie, Buchbinder, Schattner, Spike and Grimshaw2012). Initial steps in planning and identifying appropriate intervention strategies should include identifying barriers and facilitators that are subsequently mapped to potential intervention strategies (Craig et al., Reference Craig, Dieppe, Macintyre, Michie, Nazareth and Petticrew2008), thereby providing the basis for a context-appropriate implementation plan (Michie & Prestwich, Reference Michie and Prestwich2010; Puchalski Ritchie et al., Reference Puchalski Ritchie, Khan, Moore, Timmings, van Lettow, Vogel, Khan, Mbaruku, Mrisho, Mugerwa, Uka, Gülmezoglu and Straus2016).

In line with the literature, a key feature of parent involvement interventions is that impact also depends on their precise delivery mechanisms to the parents and adherence to or consistent implementation of the intervention (Michie & Prestwich, Reference Michie and Prestwich2010). Examples include engaging parent-to-parent support groups and their interaction with teachers and children, helping parents support their children’s schooling at home, supporting community conversations, or training parents as advocates. Evidence has also shown the usefulness of addressing issues in public forums, as parents can benefit from the social aspect of working in peer groups (Puchalski Ritchie et al., Reference Puchalski Ritchie, Khan, Moore, Timmings, van Lettow, Vogel, Khan, Mbaruku, Mrisho, Mugerwa, Uka, Gülmezoglu and Straus2016; Spier et al., Reference Spier, Britto, Pigott, Roehlkapartain, McCarthy, Kidron, Song, Scales, Wagner, Lane and Glover2016).

Limitations

The value of this review was its inclusion of a rigorous literature search, use of independent reviewers during data search, extraction, and synthesis, as well as following PRISMA guidelines, which provide a transparent, complete, and accurate account of why the study was done and what we did and what we found (Spier et al., Reference Spier, Britto, Pigott, Roehlkapartain, McCarthy, Kidron, Song, Scales, Wagner, Lane and Glover2016). Nonetheless, the findings must be considered in the context of several limitations. First, conducting a meta-analysis was impossible due to the heterogeneity of both included interventions and outcome measures. Second, the studies also showed significant variabilities in design, focus and quality due to the various contexts, intervention types, duration, sample sizes, and assessment tools. In addition, the sample sizes across the studies on parental involvement were small, which limits the generalisability of the study findings.

Summary and Conclusions

In the current review, we sought to identify and summarise the evidence on parental involvement interventions supporting the education of school-aged children with disabilities. The review has generated valuable insights into the range and types of interventions encouraging parent involvement in the education of children with disabilities. The study also underlined the need for more high-quality research to increase our understanding of the nature and impact of parental involvement in the education of children with disabilities. The findings also reveal the gap and need to involve parents of children with a wide range of impairments, focusing research on low-income settings and increasing sample sizes to improve the generalisability of the results. Most importantly, the review further highlights the demand for context-specific interventions to promote the involvement of parents of children with disabilities in schooling, especially in low- and middle-income settings.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/jsi.2023.11

Acknowledgements

The authors of this paper would like to acknowledge Dr Daksha Patel and Dr Sarah Polack for their professional guidance and for making this work possible.

Financial support

This review did not receive a specific grant from any funding agency, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.