Introduction

The pre-colonial Nambya state of north-western Zimbabwe has been known since early colonial times (Kearney Reference Kearney1907), yet has received little scholarly attention. While a historical synthesis of the state has been attempted (Ncube Reference Ncube2004) and some archaeological research undertaken (Makuvaza Reference Makuvaza2008), these have been limited in scope. The new research summarised here was conducted under the Volkswagen Foundation funded research project The Past in the Present: the Zimbabwe Culture and other Archaeological Heritage in north-western Zimbabwe (Shenjere-Nyabezi Reference Shenjere-Nyabezi2016).

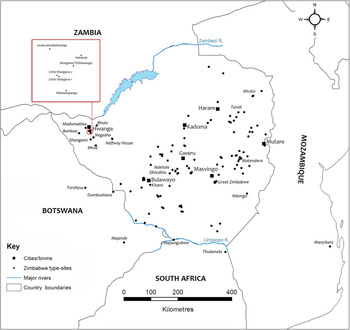

The Zimbabwe Culture is named after the site of Great Zimbabwe, located near Masvingo, Zimbabwe. This culture represented a major civilisation that flourished in southern Africa between the twelfth and eighteenth centuries AD. Its most notable attribute is its stone architecture that comprises freestanding dry-stone walls, and it is generally agreed that these monumental walls were constructed as symbols of the power, wealth and prestige of the ruling classes (Pwiti Reference Pwiti1996; Pikirayi Reference Pikirayi2001). At least 300 Zimbabwe Culture sites are known in the region; most of these are found on the Zimbabwe plateau, while others are in Botswana, Mozambique and South Africa (Figure 1). Archaeological research has shown that the sites were centres of political power, with the larger sites representing capitals of the Nambya state system (Shenjere-Nyabezi et al. Reference Shenjere-Nyabezi2020).

Figure 1. Map showing Zimbabwe Culture sites in Zimbabwe and southern Africa (figure by the authors).

The Zimbabwe Culture, oral traditions and the origins of the Nambya state

The Zimbabwe Culture in north-western Zimbabwe is best known from the stone-built sites of Shangano, Bumbuzi and Mtoa. Nambya oral traditions identify these sites as successive capitals of the Nambya state (L. Chinyathi, pers. comm.). Shangano is named as the first capital of the state; from there it was moved to Mtoa and subsequently to Bumbuzi. Even today, these three sites are considered sacred and are an important part of Nambya cultural identity.

In past decades, the political developments associated with the Zimbabwe Culture were understood in linear evolutionary terms. Against this background, the Mapungubwe state—believed to have been the first Zimbabwe Culture state system in southern Africa (Huffman Reference Huffman1996)—developed in the Shashi-Limpopo basin during the eleventh century AD and collapsed during the thirteenth century. The Zimbabwe state, based at Great Zimbabwe, was its direct successor. It too collapsed during the middle of the fifteenth century AD. From Great Zimbabwe, power shifted to Khami, capital of the Torwa state in south-western Zimbabwe and then to the Mutapa state in northern Zimbabwe. Nambya has been viewed from this traditional interpretative framework as one of the Zimbabwe Culture states, and oral traditions would appear to support this. The research summarised here was undertaken to investigate the origins and development of the Nambya state from an archaeological perspective, focusing on the site of Shangano, and to consider the stone buildings in north-western Zimbabwe in the context of the state and the wider political developments in the region.

Archaeological surveys

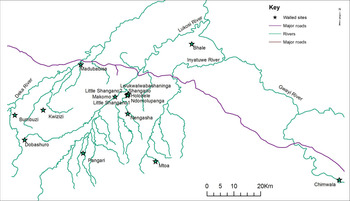

In order to establish an archaeological base for understanding the spatial correlates of the Nambya state, systematic surveys were undertaken in the Hwange District of north-western Zimbabwe. The surveys used the three capital sites, Shangano, Bumbuzi and Mtoa, as points of reference, and also drew on local community knowledge. During the surveys, 17 new Zimbabwe Culture stone buildings were recorded, bringing the local site record to 21. These new sites vary in size and architectural style, but are all within a 50km radius of the three capitals (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Location map of Zimbabwe Culture sites in Hwange District (figure by the authors).

Architectural assessment

The Zimbabwe Culture has traditionally been divided into three phases, based predominantly on architectural style and other considerations: the Mapungubwe phase (AD 1050–1250), the Zimbabwe phase (AD 1250–1450) and the Khami phase (AD 1450–1650). Wall classification was based on studies at Great Zimbabwe by Anthony Whitty in the 1950s. Here, Whitty defined four wall styles: a P style (the earliest); a PQ style (intermediate); Q style (considered the finest); and finally, R style, which was thought to be associated with the decline of Great Zimbabwe (Whitty Reference Whitty1966). This classification assumed a linear increase in quality and, as such, wall style was accorded chronological significance. Stone buildings across the region were then assigned to the different phases based on this classification. Against this background, the current research sought to classify the north-western Zimbabwe stone buildings in order to situate them in time and space within the context of the Zimbabwe Culture.

Assessment of the construction techniques of the 21 documented stone buildings in the Hwange District has raised issues that challenge the traditionally accepted relationship between wall style and chronology. There is a notable occurrence of different wall styles within and between sites, to the extent that assigning sites to specific phases associated with progressive political developments becomes problematic (Shenjere-Nyabezi et al. Reference Shenjere-Nyabezi2020). The site of Shangano, for example, exhibits all styles from P–R within the different enclosures (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Different wall construction styles at Shangano (figure by the authors).

The site of Bumbuzi, on the other hand, is built only using the PQ and Q styles, while the buildings at Mtoa exhibit a style suggestive of R. Intriguingly, walls at Mtoa exhibit decorative motifs, such as chevrons, which, in the traditional classification, were associated with the ‘highly developed’ Q style—as seen on the Great Enclosure at Great Zimbabwe (Figure 4). Other stone buildings in the Hwange District also show combinations in styles.

Figure 4. Chevron pattern at Mtoa (a) and Great Zimbabwe (b) (figure by the authors).

What emerges from the architectural assessment of the Hwange District sites is a picture that is inconsistent with the traditionally accepted correlation between architectural style and chronology. Thus, architectural style becomes a questionable basis for the division of the Zimbabwe Culture and therefore any inferences on the linear evolution of Zimbabwe Culture state systems. Our research has demonstrated that the earliest dates for Shangano and the Nambya state (fourteenth century AD) support the argument for a parallel, multi-linear developmental framework for the Zimbabwe Culture state systems.

Archaeological excavations at Shangano

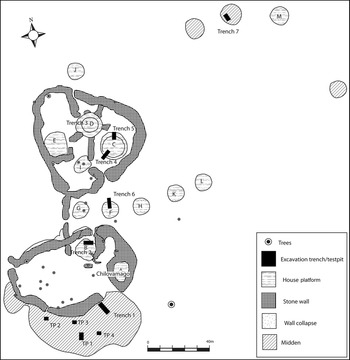

Excavations were conducted at the site of Shangano and at two smaller Zimbabwe Culture sites. The Shangano site is divided into distinct areas, within which the two semi-detached stone enclosures and an extensive midden are the most distinct features (Figure 5). The two enclosures—designated Southern and Northern Enclosures—encompass house platforms. Two smaller middens, associated with a house platform, were recorded around 400m to the east of the main site.

Figure 5. Shangano site plan (figure by the authors).

The excavations investigated parts of the main midden, the smaller middens, one platform in the Southern Enclosure (Platform B), two platforms in the Northern Enclosure (Platforms C & D) and Platform F, located between the Northern and the Southern Enclosures. The excavations on the main midden recovered a variety of finds, including graphite-burnished pottery, faunal remains, metal objects, shell and imported glass beads. Two trenches were excavated on Platform C, whilst Platform D yielded the most notable results: six well preserved house floors at different levels (Figure 6). Excavations on Platform C revealed a circular stone house foundation. The structures, features and floors of Platforms C & D provide new data for understanding the architecture, organisation of space and the duration of occupation.

Figure 6. Photograph showing exposed house floors at different levels in Platform D (figure by the authors).

Discussion and conclusions

The results of this study demonstrate that while the dry-stone architecture was indeed a major defining cultural attribute, it must be considered within its local context, where traditional classifications and associated chronological implications do not seem to apply. The emerging evidence for the origins of the Nambya state seems to be more consistent with parallel developmental trajectories for Zimbabwe Culture state systems (Chirikure et al. Reference Chirikure2018). Radiocarbon dates obtained from Shangano show that it was occupied between the fourteenth and nineteenth centuries AD (Shenjere-Nyabezi et al. Reference Shenjere-Nyabezi2020), indicating that the Nambya state developed contemporaneously with other Zimbabwe Culture states. When compared with the other more popularised pre-colonial state systems of southern Africa, the Nambya state exhibits a similar degree of complexity. Our new research in north-western Zimbabwe raises a number of issues regarding traditional approaches and necessitates a reassessment of the Zimbabwe Culture.

Funding statement

We are most grateful for the VolkswagenStiftung Senior Postdoctoral Fellowship (RE: 96 980), which supported this research.