Early modern commerce in the Americas was facilitated by factories located strategically along shipping lanes (Koot Reference Koot2011). While some, such as St Eustatius and Curacao, went on to become Dutch colonies, many did not. LaSoye is the first seventeenth- to eighteenth-century Dutch trading factory discovered in the Caribbean islands. We present here results from rescue excavations in 2018.

Interaction between early colonial powers and Indigenous residents of the Eastern Caribbean is often envisioned as subjugation by the Spanish crown (see Keegan & Hofman Reference Keegan and Hofman2016; Hofman Reference Hofman and DeCorse2019). In the Eastern Caribbean, however, colonial efforts met with armed resistance, and Europeans were vulnerable to raids by the Indigenous Kalinago. Evidence of such early interactions has been identified on three islands: Plage de Roseau, Guadeloupe (Richard Reference Richard2001); Argyle, St Vincent (Hofman et al. Reference Hofman, Hoogland, Boomert, Martin, Hofman and Keehnen2019); and La Poterie, Grenada (Hofman & Hoogland Reference Hofman and Hoogland2018). These sites demonstrate how the material innovations and economic relationships of such engagements were not one-sided. Given the limited number of sites identified, however, understanding early colonial history requires more evidence, which LaSoye can partly provide.

LaSoye in historic context

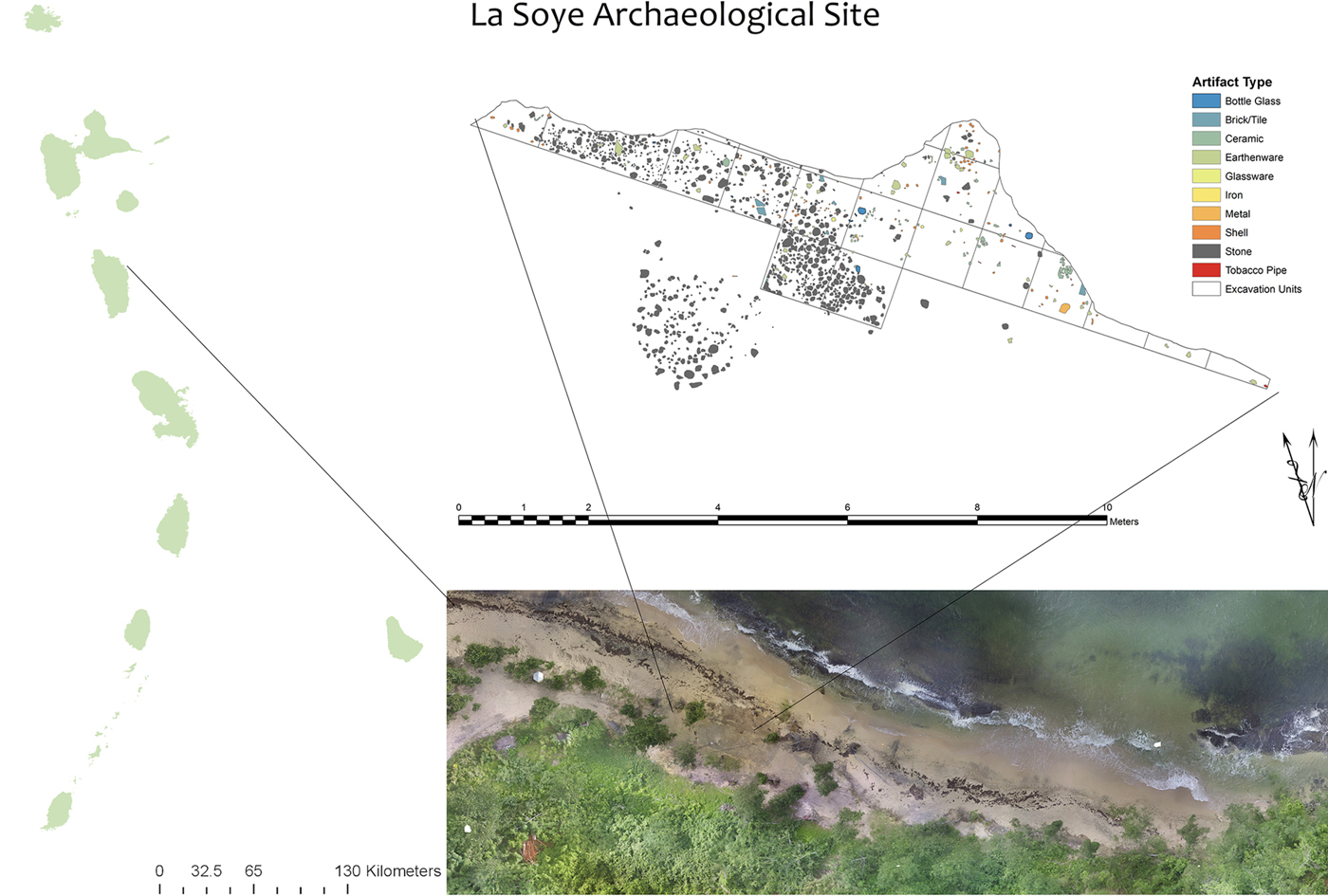

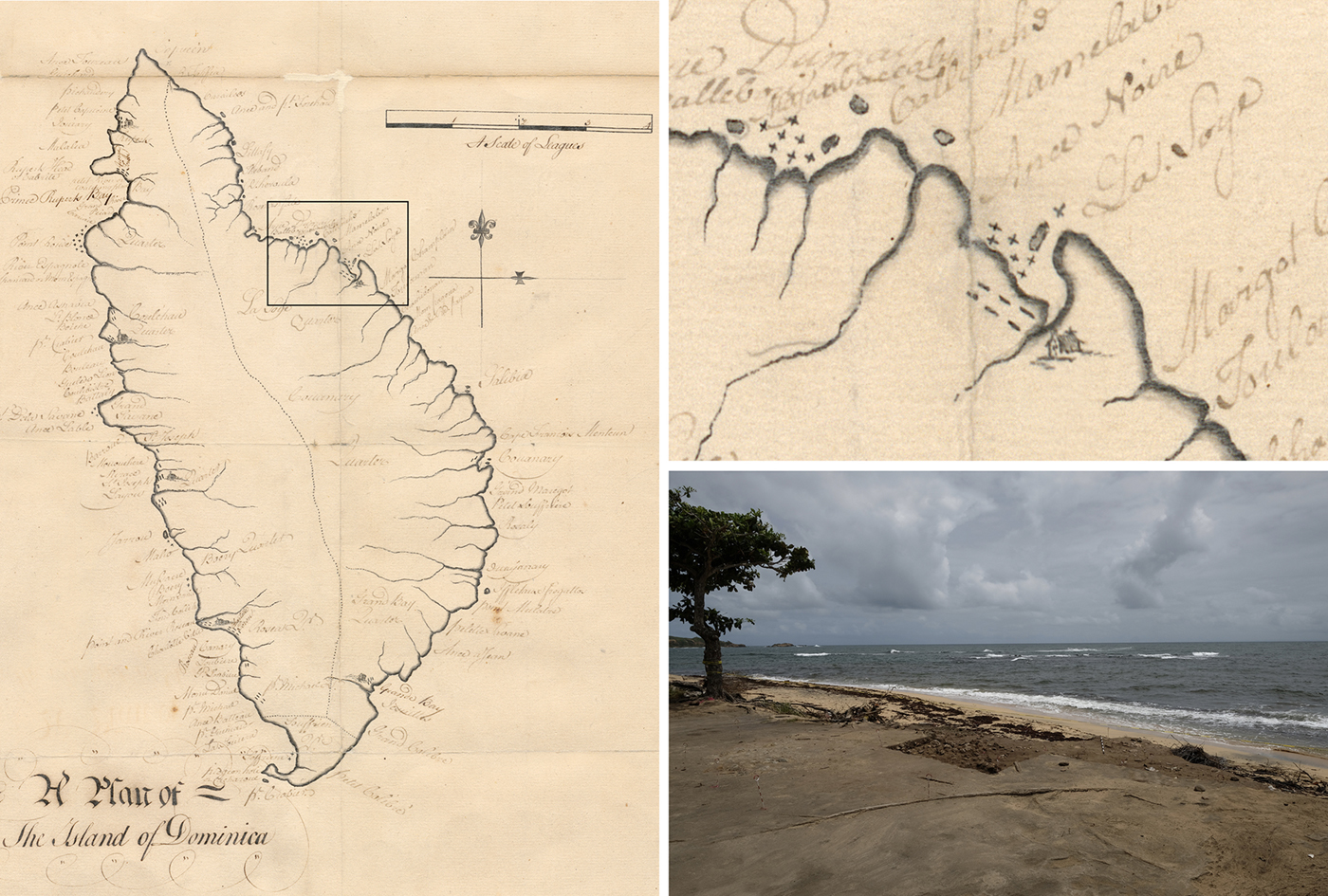

Located on the north-eastern coast of Dominica, LaSoye was ideally situated both as a trading hub for European factories and as a coastal settlement for Kalinago (Figure 1). The neighbouring islands of Les Saintes, Guadeloupe and Marie Galante, whose coastal settlements would have been visible from LaSoye, were separated from Dominica by relatively calm waters, allowing considerable traffic between these islands via canoes. Additionally, ships approaching from the east would have found a small harbour made safe by a headland (LaSoye Point) and a reef that acted as a breakwater (Figure 2). Ocean-going vessels found safe harbour here after the voyage from the Canary Islands. Traces of a colonial road, identified through survey, suggest that settlement at LaSoye was important commercially. Before the island's official colonisation in 1763, LaSoye apparently served as a trading factory for Kalinago and Europeans. By this time, Dominica had become one of the few remaining strongholds of Eastern Caribbean Indigenous people, despite violent raids and eviction by Europeans.

Figure 1. Clockwise from left: location of LaSoye in the Eastern Caribbean; site plan of rescue excavations; aerial photograph of site (credit: M.W. Hauser).

Figure 2. Clockwise from left: ‘Windward Islands: Dominica. Map of the island giving place names around the coast’ by an anonymous cartographer, c. 1760. TNA MFQ 1/1173/1, courtesy of the UK National Archives; close-up of the map depicting La Soye Point and a village located in the vicinity prior to British annexation in 1763; the site looking north to Marie Galante.

Historical evidence for early engagement between Indigenous peoples and Europeans is three-fold. Within the first 30 years of Spanish occupation of the Greater Antilles, forced labour and disease had severely reduced the Taino population; the Spanish replaced these labourers with Indigenous populations from the Lesser Antilles and Africa. In 1535 the Spanish declared that its shipping route with Panama would run between Dominica and Guadeloupe. Prince Rupert Bay on Dominica's leeward side was designated as a key provisioning point.

Sir Francis Drake and John Hawkins (the first English slave trader) described a village in the vicinity of LaSoye in the 1590s where Indigenous people “groweth great store of Tobacco: where most of our English and French men barter knives, hatchets, sawes and such like yron tooles in truck of Tobacco” (Honychurch Reference Honychurch1997; Andrews Reference Andrews2017 [1972]: 185). This industry, combined with regular raids by the Kalinago on other islands and on European ships, meant Dominica emerged as a locus of commercial activity.

Dominica was also strategic for the Dutch. Privateering became an important way to arm their merchant ships both for hijacking and defending themselves against attack from foreign ships and pirates. The Dutch were initially interested in establishing trading posts and ‘factories’ for commercial activities and trading European manufactured goods for tobacco and food.

The Kalinago at this time, particularly those living in Dominica, led sporadic raids on European settlements in the Greater Antilles and neighbouring islands. During their raids, the Kalinago took prisoners, including Europeans and enslaved Africans. At the same time, surviving Taino were migrating to the Leeward Islands. Dominica's population during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, therefore, was plausibly a mixture of predominantly Kalinago, with some Taino, Africans and Europeans.

LaSoye in archaeological context

Little is known of early settlements in Dominica, but the archaeology of European factories and indigenous settlements in the Caribbean can detail early colonial commercial relationships, revealing how engagement unfolded. Sites that document such evolution are rare, however, due to difficulties locating them and to site destruction during the development of holiday resorts. In the Eastern Caribbean, Argyle in St Vincent and La Poterie in Grenada provide comparable evidence of sixteenth-century European engagement, but Argyle represents only a brief colonial occupation, and La Poterie is a non-stratified deposit. Stratified deposits and intact cultural features at LaSoye provide good dating contexts and a rare opportunity to explore European-driven change.

In 2017, Dominican anthropologist and historian Lennox Honychurch identified the site of LaSoye after storm surges exposed archaeological deposits on the beach (Figure 3). These included materials of European and indigenous origin associated with commerce and domestic use. Sixteen square metres were excavated to mitigate areas at risk from tidal erosion. Excavations revealed structural foundations overlying a surface occupation midden, alongside an extramural activity area. European trade goods found in association with indigenous materials suggest that it was a trading post.

Figure 3. Representative sample of surface finds documented after Hurricane Maria (credit: M.W. Hauser).

The material culture recovered from LaSoye contains considerable ceramics, glassware, tobacco pipes and small finds of European origin. All the clay pipes were found in association with the store house extramural activity area; 99 per cent of these (n = 113) were identified as Dutch (Figure 4). Of these fragments 36 were bowls, and 11 maker's marks could be identified that reliably date to before the 1730s (Table 1). The ceramic assemblage contained 636 sherds comprising a minimum 317 vessels (Figure 5). By far the largest component was pottery putatively made by Indigenous peoples and identified as ‘Amerindian’ (n = 210), although only a few sherds (5) could be accurately assigned to a type such as Suazoid (n = 1) or Cayo (n = 2+). Unidentifiable local coarse earthenware comprises a large part of the assemblage (n = 60). Imported European or Asian trade wares included 6 different types, featuring French faience (c. 1600–1840), Delft (c. 1600–1800), Slipware (c. 1500–1900), and French Coarse Earthenware. Delft was the most numerous imported ceramic (n = 164), followed by French faience (n = 95). Most trade ceramics were found in association with the stone floor and its extramural activity area.

Figure 4. Dutch pipe bowls recovered from the site (credit: M.W. Hauser).

Figure 5. Artefacts recovered from foundation levels and extramural activity area. Clockwise from top left: bottle glass; Dutch tin-enamelled earthenware; lead shot with mould (credit: M.W. Hauser).

Table 1. Dutch Pipe Bowls’ marks and dates.

The subfloor context was dated at Beta Analytic from charcoal calibrated using the high-probability density range method to AD 1477–1647 (cal 95%) and 1540–1601 (cal 37.4%). Chinese export porcelain (n = 6), Chinese stoneware (n = 1) and Spanish Merida ware (n = 7) (c. AD 1590–1700) were all found in subfloor contexts. Other materials recovered from this level include coarse earthenware, glass beads, shell pendants, quartz crystals and trade bells (Figure 6). Cayo pottery, also found in this deposit, is indigenous to the Lesser Antilles (AD 1400–1640) (Boomert Reference Boomert2009, Reference Boomert2011). The presence of Cayo pottery and syncretic ceramic forms indicate social and economic interactions between the Europeans and local Indigenous groups. Recovery of vessels containing food remnants and stockpiles of artefacts suggest that the site was abandoned suddenly, perhaps due to Kalinago raiding, French attack or English incursion.

Figure 6. Artefacts recovered from subfloor context. Clockwise from top left: shell beads carved in the shape of Zenaida doves; European glass bead; resin, possibly from the LaSoie tree for which the point is named (credit: M.W. Hauser).

Sites where strangers met in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries are at risk from coastal erosion due to changing climate conditions, sea levels and increasingly intense storms. Documenting them is important as they provide opportunities to examine early interactions and trade between Indigenous peoples, Africans and Europeans.

Acknowledgements

This paper is dedicated to members of the Dominican community affected by Hurricane Maria. We would also like to thank those that visited and volunteered on the site, especially Mitchell LaVille and Anile and Paul Crask. The fieldwork was funded by a Northwestern University Research Grant.