Article contents

Tracing copper in the Cypro-Minoan script

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 19 July 2016

Abstract

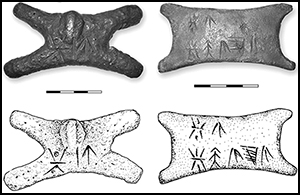

The Cypro-Minoan script was in regular use on the island of Cyprus, and by Cypriot merchants overseas, during the Late Bronze Age. Although still undeciphered, sign-sequences inscribed on miniature copper ‘oxhide’ ingots and on associated clay labels may hold a clue to their purpose. The ingots were previously interpreted as votive offerings inscribed with dedications. Here, it is suggested instead that these extremely pure copper miniatures were produced as commercial samples, and were marked with a brand denoting their high quality and provenance, such as ‘pure Cypriot copper’.

- Type

- Research

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Antiquity Publications Ltd, 2016

References

- 7

- Cited by