Introduction

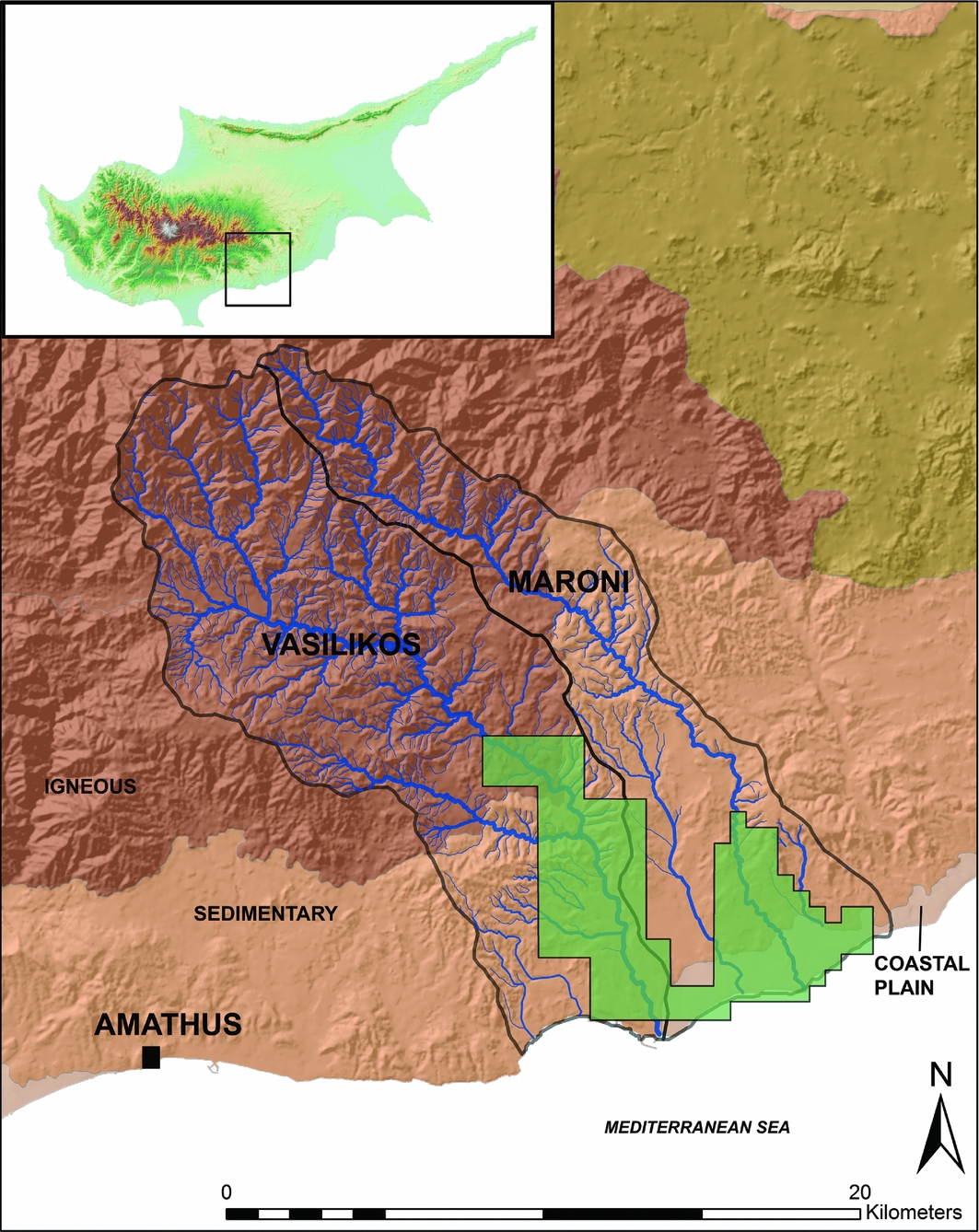

The narrative of socio-political development on the semi-arid island of Cyprus during the early first millennium BC (c. 1100–500) has focused largely on the institutions, practices and material culture of major centres and their interrelationships with growing maritime networks. Less studied are the landscapes surrounding these coastal and inland towns, which helped condition the increasing wealth and power of authorities through the management of agropastoral and metal goods, and through the creation of new mortuary, ritual and community spaces (Iacovou Reference Iacovou and Webb2014). These regional contexts, whose settlements and land-use practices have now been recorded through several survey projects, provide a rich yet under-used source of material for investigating social transformations during this period. Ongoing interdisciplinary work in the Vasilikos and Maroni Valleys of south-central Cyprus has begun systematic analysis of these landscape changes and their long-term contexts. The project is focused on a 150km2 research area situated 20km east of the ancient polity of Amathus, extending from the central Troodos massif down to the coast (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The Vasilikos and Maroni Valleys in south-central Cyprus, showing survey area (green) and physiographic regions, plus the centre of Amathus. 20m DEM resolution. Created by C. Kearns, data from GSD of Cyprus.

Re-survey and spatial analysis

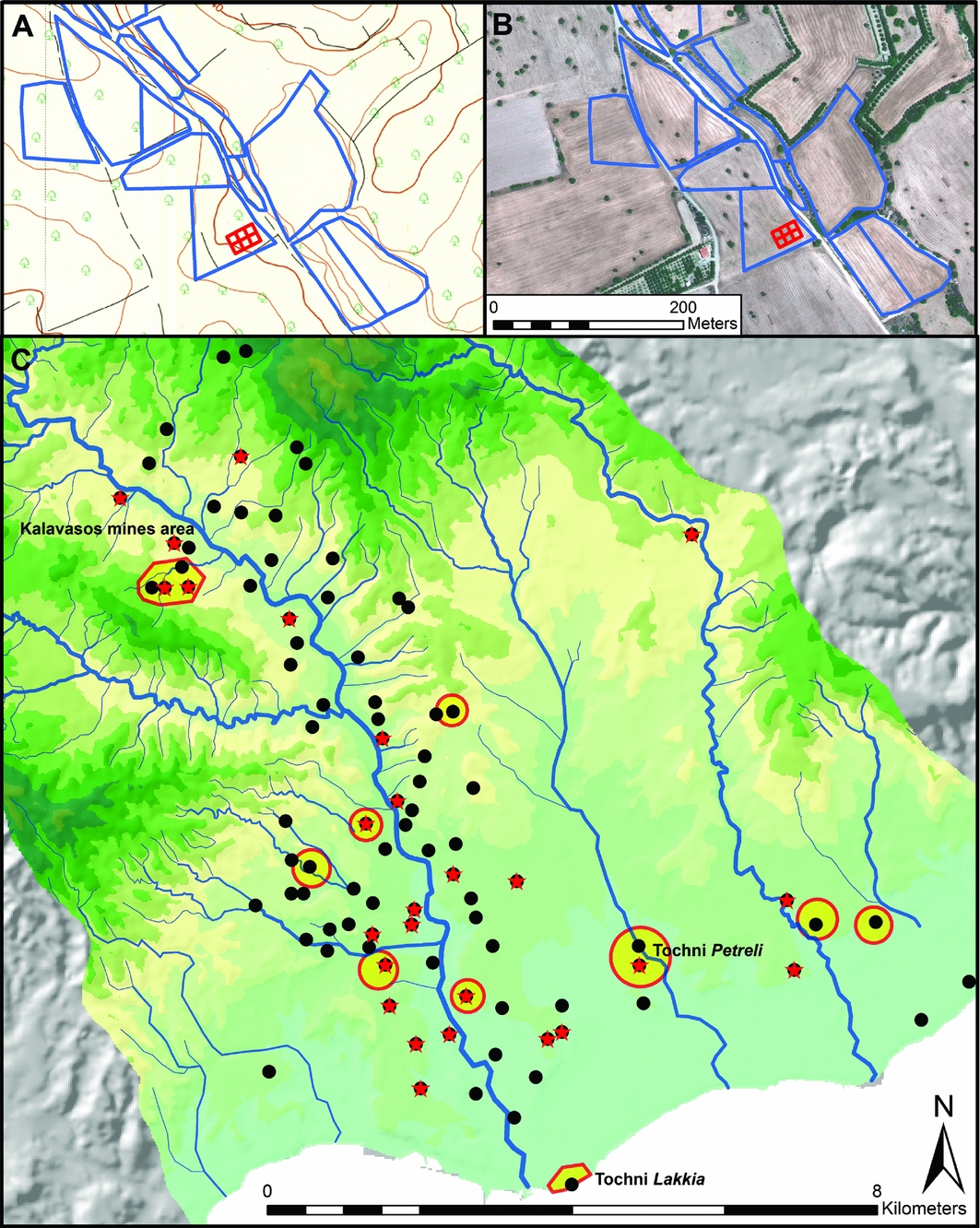

From 2012–2015, an initial stage of research involved the re-surveying of previously identified sites (Manning et al. Reference Manning, Bolger, Swinton and Ponting1994; Todd Reference Todd2004), GIS-based spatial analyses and palaeoenvironmental research. In addition to the digital mapping of approximately 90 sites and the study of archived materials (Georgiadou in press), 10 sites were targeted in order to investigate landscape continuity and inter-site connections, in contexts ranging from coastal plains to inland alluvial terraces (Figure 2). Artefacts and features such as check dams, terrace walls, tombs, metal-working areas and building materials were combined in a geospatial database along with data on soils and geology, hydrology and land use, as well as digital elevation models and QuickBird satellite imagery. In order to study changing water availability, stable isotope analysis was undertaken on archaeological charcoal as a proxy record for precipitation. Preliminary results indicate wet conditions with the onset of the eighth–seventh centuries BC, which would have probably reduced interannual variability in rainfall and made growing conditions more consistent in this semi-arid environment (Kearns Reference Kearns2015).

Figure 2. Example of survey at Tochni Petreli: 1:5000 topographic map, 2m contours (A) and QuickBird satellite image (B). Material from c. 900–500 BC, with settlements (black), cemeteries (red stars), and targeted re-survey sites (yellow). 20m DEM resolution, 50m contours. Created by C. Kearns, data from GSD of Cyprus.

Preliminary results

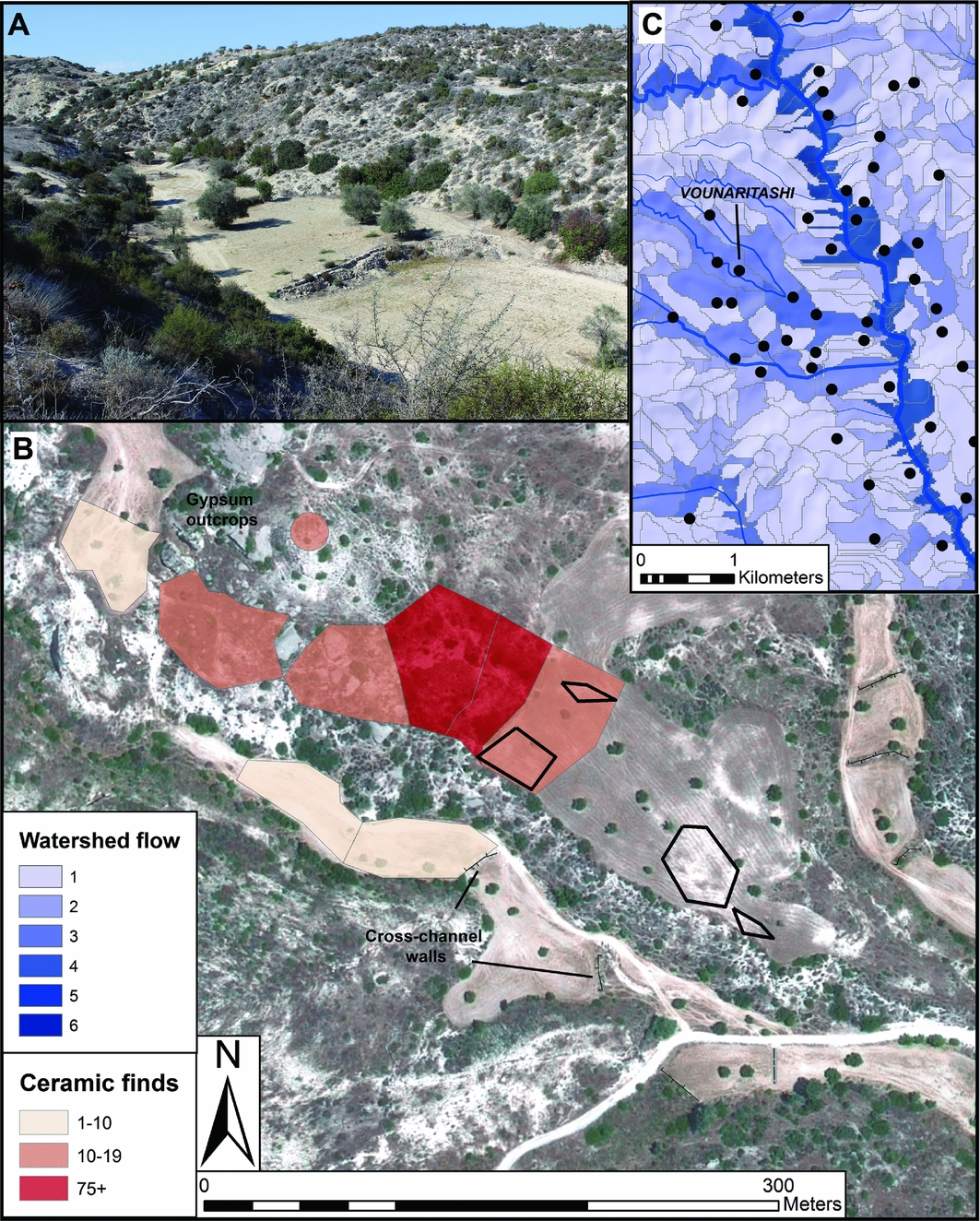

Following a period (c. 1100–900 BC) of apparently less permanent landscape occupation, significant re-investment in varied landscape contexts across the Vasilikos and Maroni Valleys is attested by sites ranging in extent from around 0.1–5ha. Surface artefact scatters suggest settled conditions as well as the possible production and distribution of goods, and indicate the intensification of agropastoral economies through land and water management (Figure 3). These scatters appear along the boundaries of numerous small watersheds and side drainages, both near river terraces and at higher elevations within fertile deposits created by palaeolandslides. Communities probably re-used pre-existing check-wall systems in alluvial channels that helped to sustain rain-fed cultivation (Wagstaff Reference Wagstaff, Bell and Boardman1992). Fragments of olive presses, large-scale storage vessels and wide-mouthed bowls such as mortaria suggest the production, redistribution and consumption of agricultural goods that included olive oil. Survey of one site, Kalavasos Vounaritashi, has recorded dense clusters of building stone and concentrations of storage vessels that point to integrated agropastoral practices, processing activities and domestic occupation. Future work on environmental proxies (e.g. sediments, charcoal, faunal remains) will aim to clarify the chronology of sites and wall systems, and to understand developing plant and animal economies.

Figure 3. Kalavasos Vounaritashi cross-channel walls (A), and satellite image showing re-survey and stone scatters (black) (B). First-millennium BC sites along watersheds, categorised by surface flow, of Vasilikos River (C). Created by C. Kearns, data from GSD of Cyprus.

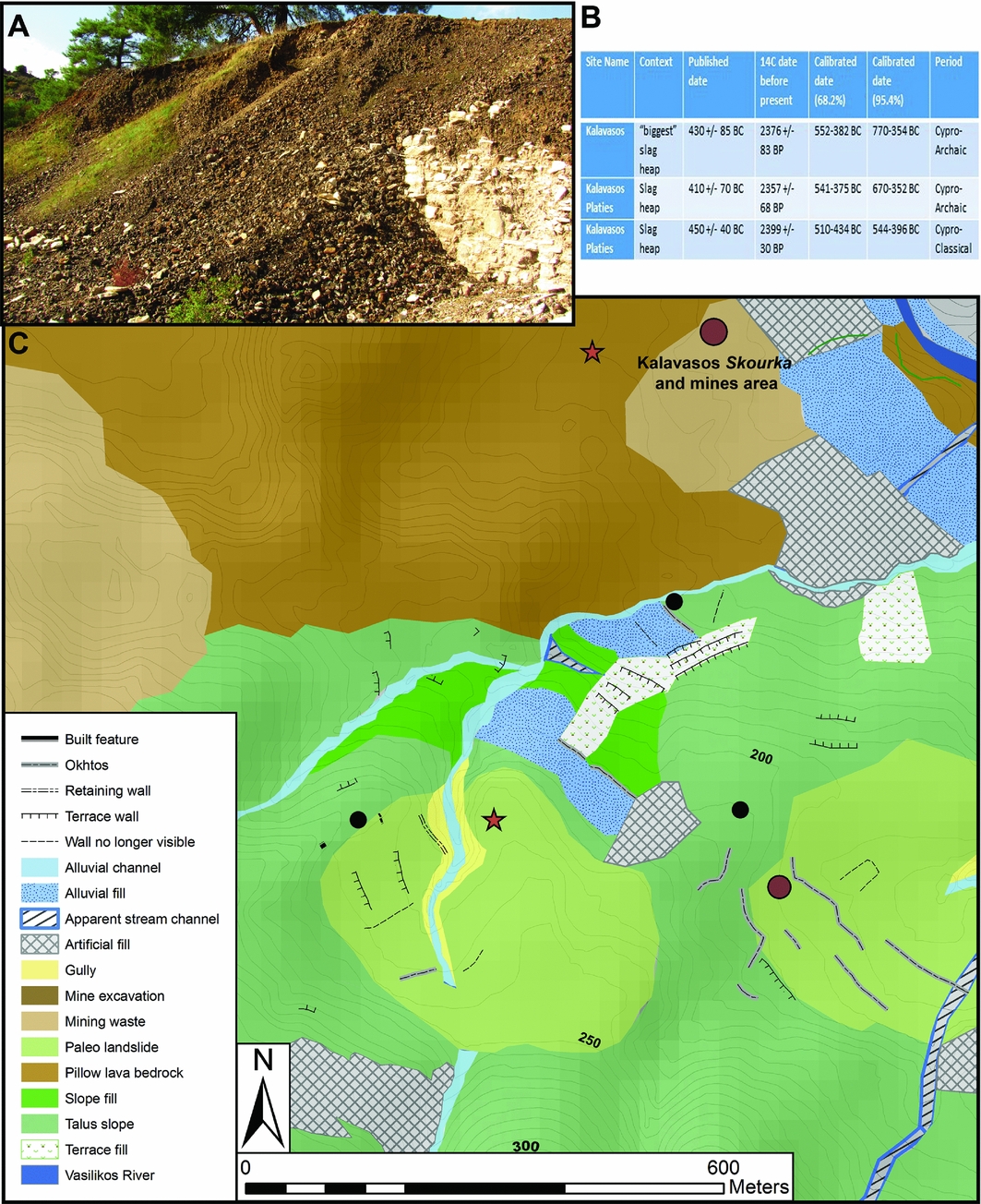

Radiocarbon dates from large slag heaps in the Vasilikos Valley indicate copper production, which may have involved regional authorities such as Amathus staking claim to metal resources (Kassianidou Reference Kassianidou2013) (Figure 4). Several sites with scatters of copper slag cluster at the interface between sedimentary and igneous geologies with access to mines, water sources, fields and gathering places such as ritual shrines. East–west routes, as well as coastal anchorages such as the site of Tochni Lakkia, facilitated interregional connections and mobility between people and goods.

Figure 4. Photograph of slag covering remains of fifth-century BC ritual building near Kalavasos Skourka (A). Radiocarbon dates from slag heaps in Kalavasos mines area from Kassianidou (Reference Kassianidou2013: 75) (B). Geomorphological map of settlements (black) and tombs (red stars) near igneous pillow lavas and slag heaps (brown circles) (C). 5m contours. Created by C. Kearns, data from GSD of Cyprus.

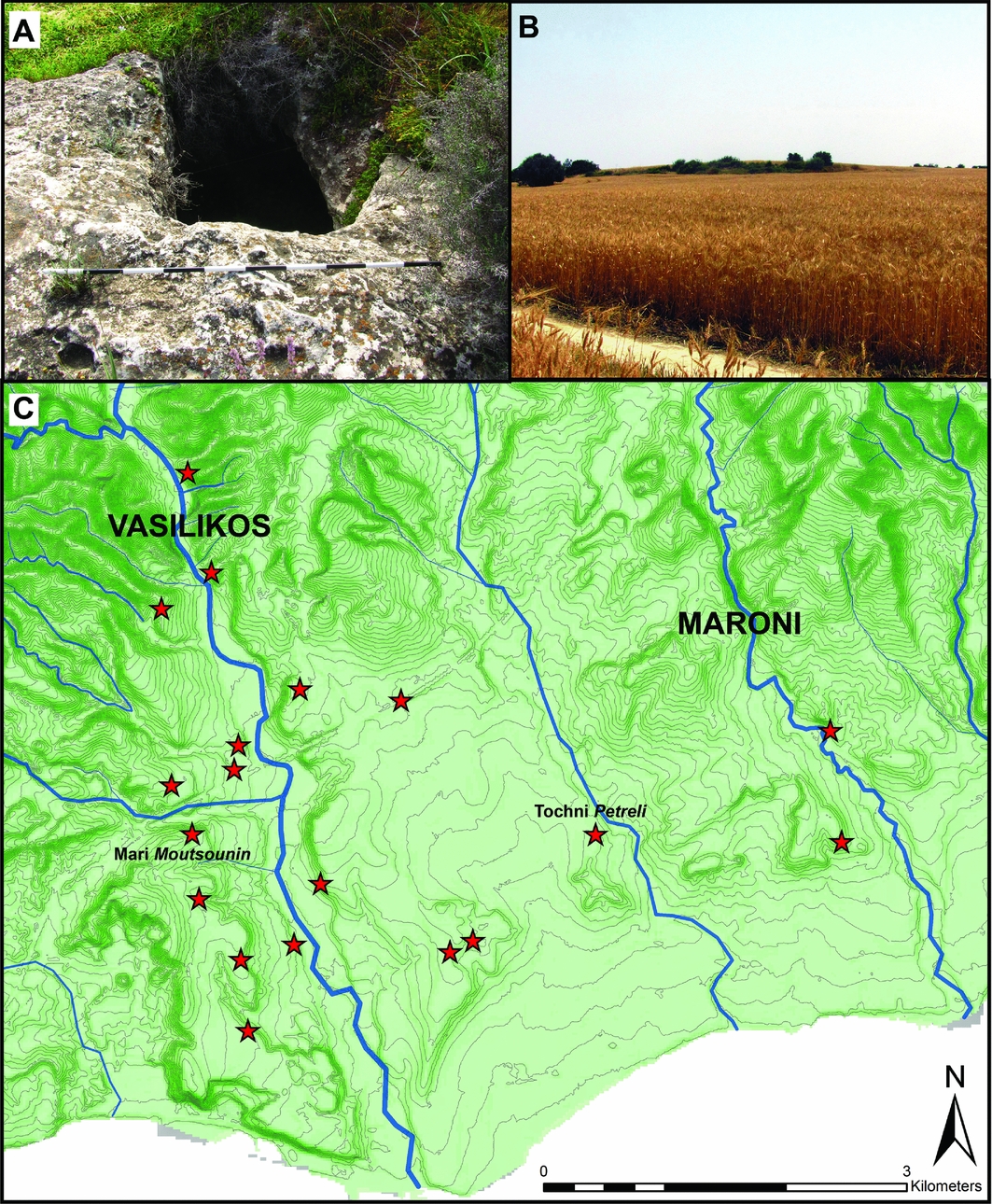

The fieldwork already undertaken has also revealed the creation of distinct mortuary landscapes along alluvial ridges and raised above the flatter coastal plain, where marine terraces conspicuously stand out as landmarks (Figure 5). Intervisible clusters of burials, cut into limestone, echo broader contemporary patterns in the demarcation of new extramural burial places. Although only a few tombs have been excavated (e.g. Hadjicosti Reference Hadjicosti1997), their contents, including jewellery and iron swords, highlight the growth of inequalities with local elites positioning themselves in relation to social practices at larger centres. An increase in the quantity of decorated dining wares during this period—with production styles principally tied to Amathus (Georgiadou in press)—may signify feasting as a setting for the displays of social power.

Figure 5. Photograph of tomb cut into limestone at Mari Moutsounin (A), and prominent relic marine terrace at Tochni Petreli with tombs (B). 5m contour map of the lower Vasilikos and Maroni Valleys showing recorded tombs and cemeteries (red) (C). Created by C. Kearns, data from GSD of Cyprus.

Conclusion

While these investigations have begun to illuminate under-studied regional transformations, they also indicate a complex assortment of land- and water-management strategies and place-making practices that reproduced new modes of power. The results challenge the narrative of developments on Cyprus as driven by cities, and illuminate the integration of smaller settlements, production and distribution centres and local authorities in the making of social differences. Future stages of this research, including geophysics and excavation, will explore more intensively the nature of settlements, trading sites and routes of the Vasilikos and Maroni Valleys, and their relationships to long-term interregional trends and shifting environmental conditions.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank the Cyprus Fulbright Commission, the Society for the Humanities at Cornell University, Ian Todd, Alison South, Sturt Manning and the Kalavasos and Maroni Built Environments Project. Support was generously granted by the Department of Antiquities, the Geological Survey Department of Cyprus, the Cyprus University of Technology and the Cyprus Institute.