Article contents

Multispectral imaging of an Early Classic Maya codex fragment from Uaxactun, Guatemala

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 17 May 2016

Abstract

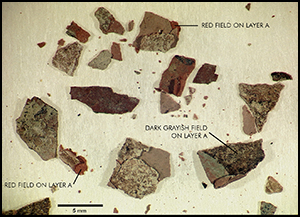

Multispectral visual analysis has revealed new information from scarce fragments of a pre-Columbian document excavated in 1932 from a burial at Uaxactun, in Guatemala. The plaster coating from decomposed bark-paper pages of an Early Classic (c. AD 400–600) Maya codex bear figural painting and possibly writing. Direct investigation of these thin flakes of painted stucco identified two distinct layers of plaster painted with different designs, indicating that the pages had been resurfaced and repainted in antiquity. Such erasure and re-inscription has not previously been attested for early Maya manuscripts, and it sheds light on Early Classic Maya scribal practices.

- Type

- Research

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Antiquity Publications Ltd, 2016

References

- 4

- Cited by