The Decapolis city of Gerasa has been the subject of continuous research since it was rediscovered by the German scholar Ulrich Jasper Seetzen in 1806 (Kruse et al. Reference Kruse, Dr Hinrichs and Müller.1854: 388–90). The Decapolis—nominally 10 cities—were located in the heavily urbanised region of what is today northern Jordan and southern Syria, with one city, Scythopolis, situated on the west bank of the River Jordan in modern Israel and Hippos East of Lake Tiberias. After the rediscovery, Gerasa was visited by numerous travellers in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (Stott et al. Reference Stott, Kristiansen, Lichtenberger and Raja2018: 1; Lichtenberger & Raja Reference Lichtenberger and Rajain press). The city, which covers more than 80ha, holds numerous monumental buildings that have been visible since antiquity. Although several maps have been produced of the site, none, however, have aimed for complete accuracy. Seetzen produced the first map of the site, published in 1854. Later travellers also made maps, largely recording the same monuments (Burckhardt Reference Burckhardt1822; Boyer Reference Boyer2016; Raja Reference Raja, Lichtenberger and Rajain press). Gottlieb Schumacher visited the site several times and his map of the site was published in 1902 (Schumacher Reference Schumacher1902).

In 1938, the Anglo-American expedition to Gerasa published a new map in the final publication of the excavations (Kraeling Reference Kraeling1938; Fisher Reference Fisher and Kraeling1938: pl. I). For decades, this was the map used in scholarship. Browning (Reference Browning1982: 83, map 3), in his book on the archaeology and history of the site, published a reduced map. When the Jerash Archaeological Project was initiated in the 1970s by the Department of Antiquities of Jordan with the support of UNESCO, another map was published in the resulting volume (Pillen Reference Pillen and Zayadine1986). In 2001, Braun et al. (Reference Braun2001: 434) published another updated map, which included monuments that have been lost over time to modern development. In 2011, Lepaon (Reference Lepaon2011: 416) published an updated map of the site, collating information from the previous maps. This incorporated spatial inaccuracies (Stott et al. Reference Stott, Kristiansen, Lichtenberger and Raja2018: 2), however, and did not include a legend, despite a numbered list of monuments being included in the article. All these maps were made using terrestrial data, compiled partly by the cartographers themselves and partly from earlier data, leading to a propagation of errors from previous maps.

Since 2011, the Danish-German Jerash Northwest Quarter Project has been producing maps of the area behind the Sanctuary of Artemis through survey and excavation (Lichtenberger & Raja Reference Lichtenberger and Raja2015, Reference Lichtenberger and Raja2017). In 2016, lidar data and orthophotography were acquired through the Royal Jordanian Geographic Society. This allowed for the precise topographic measurement of the city and its surroundings, and provided an accurate basemap for co-registering historical aerial photography. This resulted in the mapping of a large number of archaeological features (Stott et al. Reference Stott, Kristiansen, Lichtenberger and Raja2018).

During the process of combining the existing mapping with data from the aerial surveys, it became clear that an updated map of the city was required (Stott et al. Reference Stott, Kristiansen, Lichtenberger and Raja2018: 2). The authors used the 2016 data as the basis to integrate the existing mapping into a common spatial framework. Numerous nineteenth-century travellers described the site, and archaeological fieldwork has been ongoing for over a century. Hence, there is little consensus on the names of the city's monuments. In particular, early excavators chose Latin names for monuments—inappropriate for a Greek city in the Roman East. The new map has taken a pragmatic approach. Whenever possible, we use the appropriate emic terminology and names for the monuments, but when they already have well-established ‘nicknames’, we have respected these in recognition of the long history of the city and its historiography.

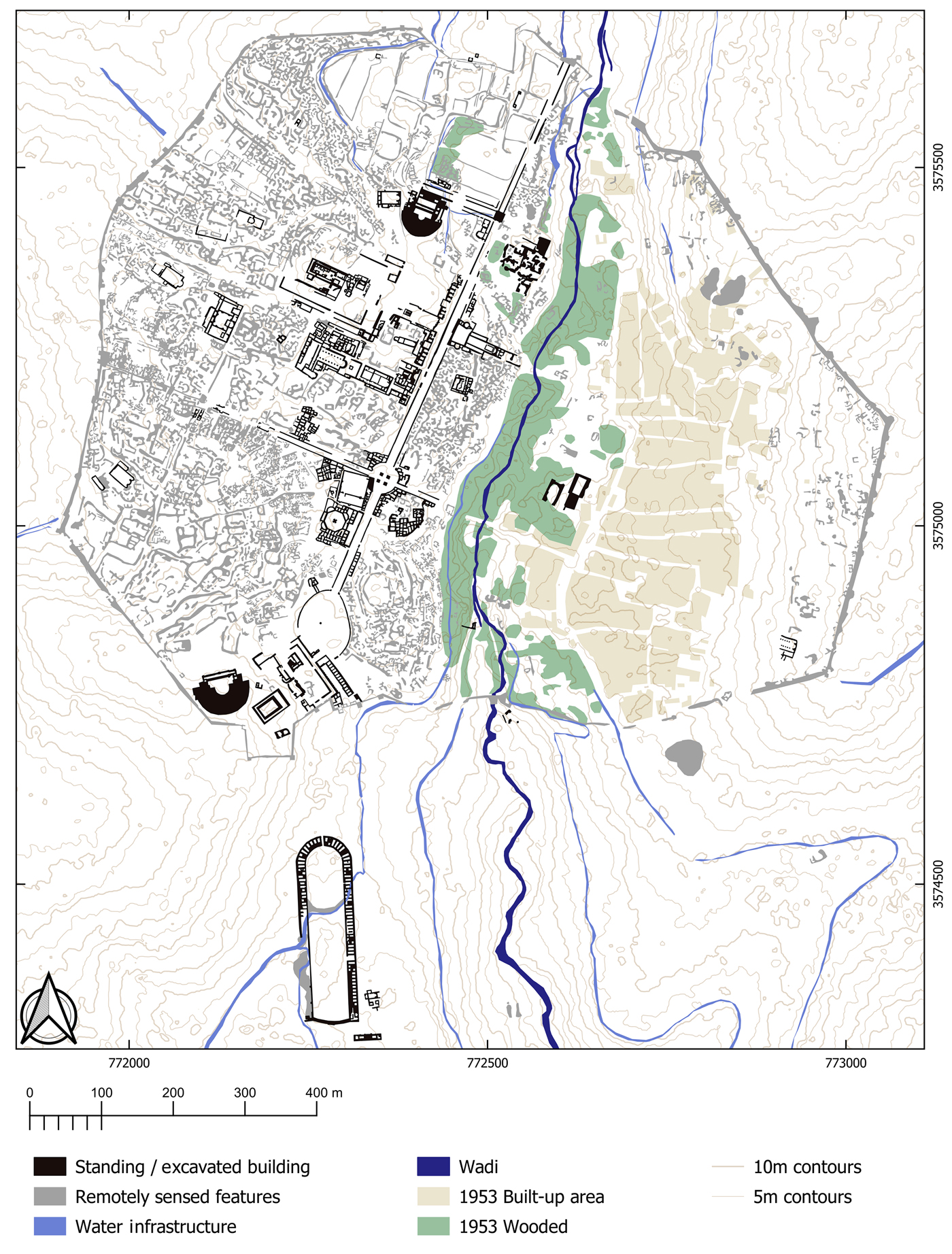

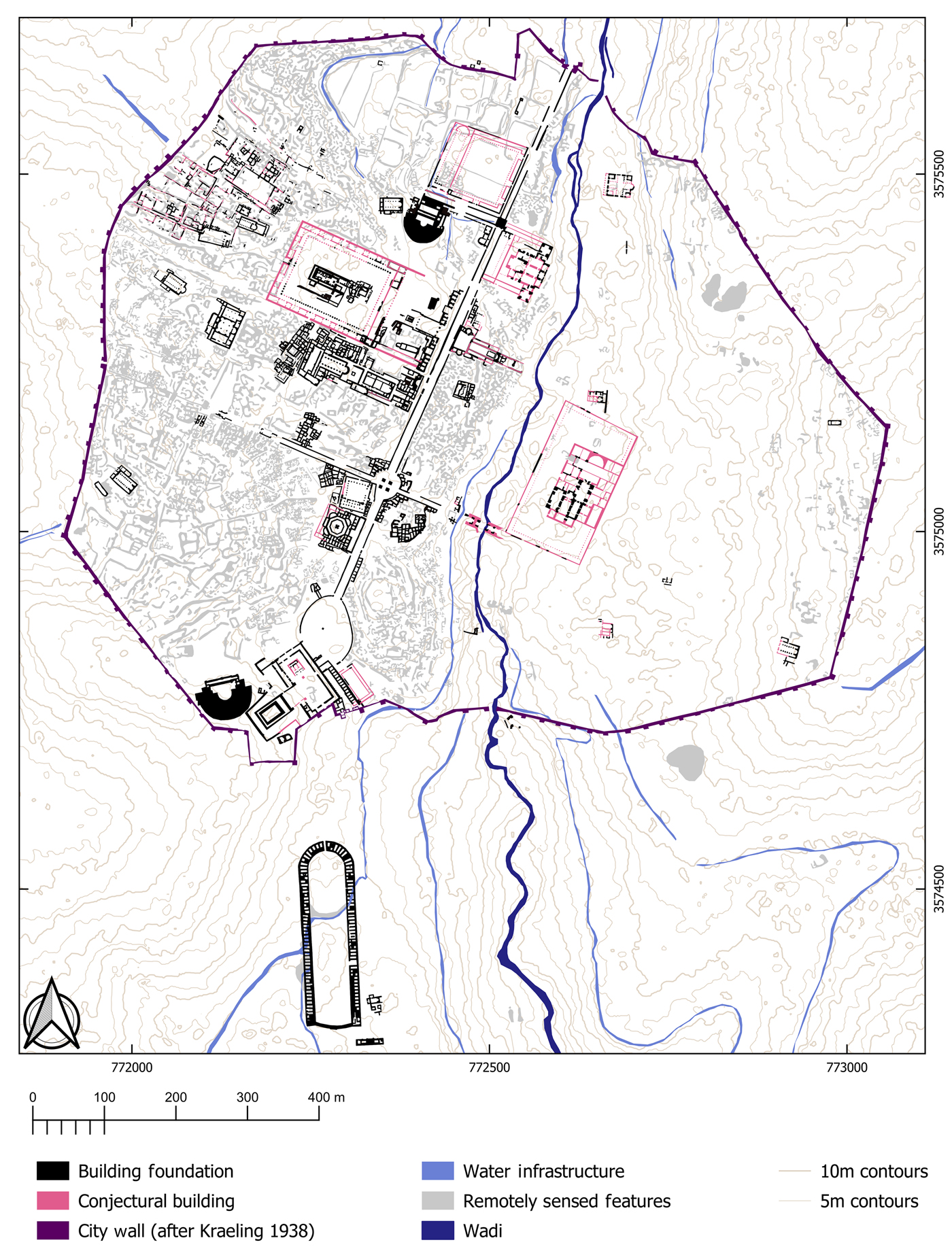

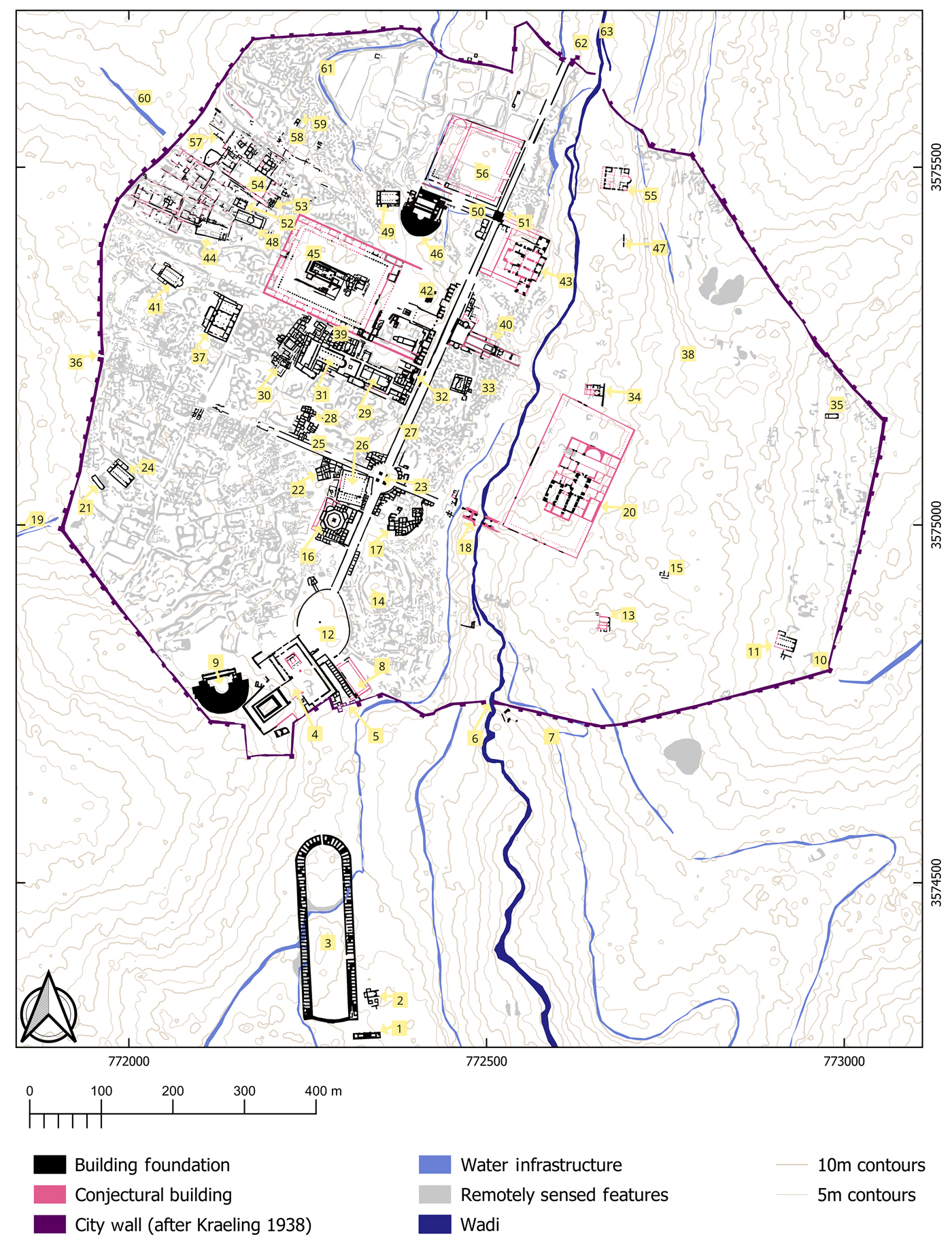

The new map provides a more accurate spatial understanding of the city, and it will prove valuable to archaeologists, cultural heritage managers and visitors (Figures 1–3). In this spirit, the map is released under a Creative Commons licence, permitting re-use and reworking of the map. This is important as our understanding is continually evolving, and this map will need to be updated as we learn more. Sharing knowledge in this way enables better collaboration, reduces duplication of effort and conforms to the international FAIR Guiding Principles for data management and data sharing (Wilkinson et al. Reference Wilkinson2016; https://dg.dk/forskningsaktiviteter/god-forskningspraksis/open-access-politik/).

Figure 1. Map of potential archaeological features derived from airborne lidar and archival photography. A large number of previously recorded and new features were recorded in the better-preserved part of the city to the west of the wadi (map © Danish-German Jerash Northwest Quarter Project: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.7609859.v1).

Figure 2. Synthesis of remotely sensed features and existing mapping from previous studies. Hypothetical building elements (after Lepaon Reference Lepaon2011; Lichtenberger & Raja Reference Lichtenberger and Raja2017) are highlighted in pink. Most of the buildings on the eastern side of the valley are no longer extant (map © Danish-German Jerash Northwest Quarter Project: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.7609859.v1).

Figure 3. As Figure 2, with points of interest highlighted (see Table 1) (map © Danish-German Jerash Northwest Quarter Project: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.7609859.v1).

Table 1. Jerash map—legend.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the funding bodies of the project: The Carlsberg Foundation, the Danish National Research Foundation (grant number: 119), Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, Deutscher Palästina-Verein, the EliteForsk initiative of the Danish Ministry of Higher Education and Science, and H.P. Hjerl Hansens Mindefondet for Dansk Palæstinaforskning.