The modification of settlement patterns and habitats in permanent open-air villages is traditionally linked to the Neolithic expansion in Central Europe and the Mediterranean. Archaeological research allows for the identification and study of these sites in order to understand the socio-economic and cultural development of the earliest farmer communities. A dearth of archaeological evidence, however, hampers our interpretation of the Neolithisation of some regions, such as northern Spain. Here, research has been traditionally focused on archaeological contexts associated with caves and megalithic structures, with some limited references to Neolithic, Chalcolithic and Bronze Age open-air sites (e.g. Gorrotxategi et al. Reference Gorrotxategi, Yarritu, Kandina and Sagarduy1995; Iriarte et al. Reference Iriarte, Mujika and Tarriño2005; Mujika et al. Reference Mujika, Peñalver, Tarriño and Tellería2009; Fernández Mier & González-Álvarez Reference Fernández Mier and González Álvarez2013; Regalado Bueno et al. Reference Regalado Bueno, San Emeterio, Ríos Garáizar, Gárate Maidagan, Marcos Gómez, Ugarte Cuetara, Líbano Silvestre, Medina-Alcaide, Moreno Larrazabal and Pérez Fernández2015; Cubas et al. Reference Cubas, Altuna, Álvarez-Fernández, Armendariz, Fano, López-Dóriga, Mariezkurrena, Tapia, Teira and Arias2016).

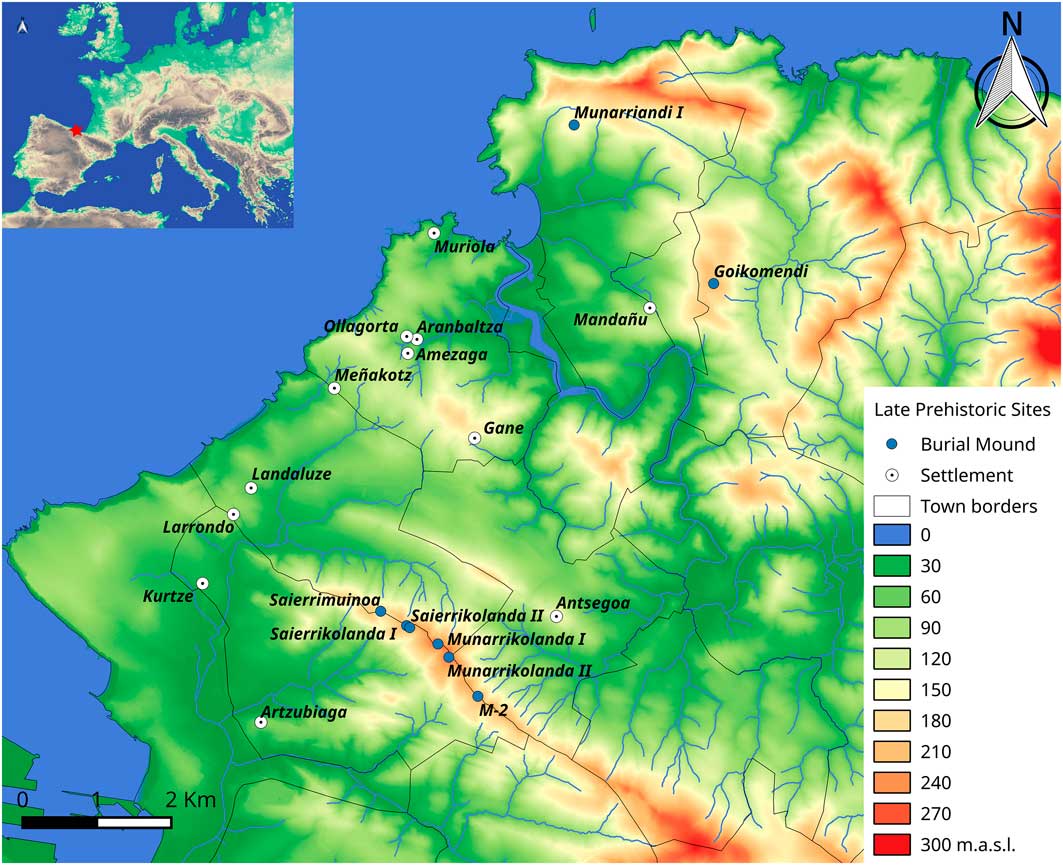

This paper presents the first evidence for coastal occupation farming communities in the Uribe Kosta region during late prehistory (Figure 1). Until recently, this unique area—located in the Basque Country, on the eastern part of the Cantabrian coast—has received little systematic archaeological research. Since 2007, however, interest in this issue has increased, and several new sites have been discovered and investigated (e.g. Rios-Garaizar et al. Reference Rios-Garaizar, Garate, Zapata-Peña, Marcos and Regalado Bueno2007).

Figure 1 Map of the Uribe Kosta area with the location of the most relevant late prehistoric sites. Base map created using LiDAR 2016 1 × 1m data (www.geoeuskadi.eus).

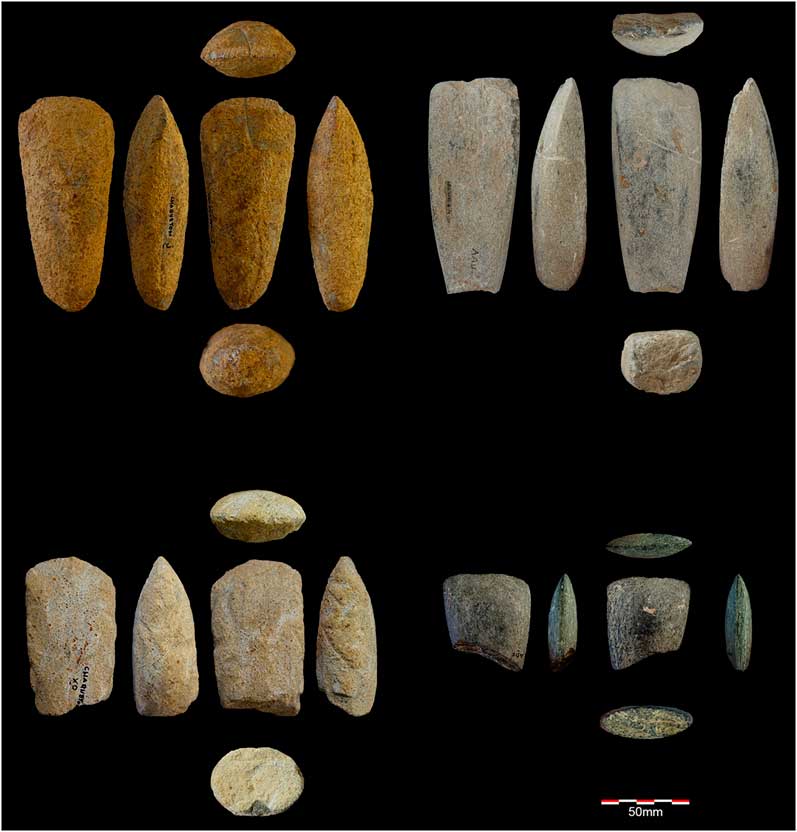

In 2013 we initiated a systematic research project (‘First Farming Communities in the Coastal Region of Biscay’), excavating newly discovered open-air sites, carrying out landscape surveys to identify burial mounds and reviewing material culture (e.g. polished tools, pressure-blade cores, arrowheads and grinding stones) (Regalado Bueno et al. Reference Regalado Bueno, San Emeterio, Ríos Garáizar, Gárate Maidagan, Marcos Gómez, Ugarte Cuetara, Líbano Silvestre, Medina-Alcaide, Moreno Larrazabal and Pérez Fernández2015; Ugarte Cuétara Reference Ugarte Cuétara2015; Rios-Garaizar et al. Reference Regalado Bueno, San Emeterio, Ríos Garáizar, Gárate Maidagan, Marcos Gómez, Ugarte Cuetara, Líbano Silvestre, Medina-Alcaide, Moreno Larrazabal and Pérez Fernández2016) (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Polished axes from Uribe Kosta sites: 1) Kurtze; 2) Landaluze; 3) Kurtze; 4) Kurtze (adapted from Ugarte Cuétara Reference Ugarte Cuétara2015).

Aranbaltza II (research campaigns from 2013–2015) and Landaluze (2015 campaign) are the most interesting of the recently discovered sites (Regalado Bueno et al. Reference Regalado Bueno, San Emeterio, Ríos Garáizar, Gárate Maidagan, Marcos Gómez, Ugarte Cuetara, Líbano Silvestre, Medina-Alcaide, Moreno Larrazabal and Pérez Fernández2015). The former yielded a Holocene palaeosoil and a Chalcolithic–Early Bronze hearth (c. 2880 and 1975 cal BC). Lithic materials included flake and blade fragments, cores and a single stemmed and winged bifacial point, along with evidence of pressure blade flaking. At Landaluze (Figure 3), a large surface lithic assemblage and two heated-stone combustion structures were excavated, the latter dating to 4240–3990 cal BC (calibrated at 95.4% confidence using OxCal 4.3 and IntCal13 calibration curve, Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009; Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Buck, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Marian Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and Van Der Plicht2013) (Figure 3) (Regalado Bueno et al. Reference Regalado Bueno, San Emeterio, Ríos Garáizar, Gárate Maidagan, Marcos Gómez, Ugarte Cuetara, Líbano Silvestre, Medina-Alcaide, Moreno Larrazabal and Pérez Fernández2015). Ongoing investigations suggest that these two sites may represent different activity areas of permanent and long-term continuous settlements.

Figure 3 Heated-stone combustion structures from Landaluze (adapted from Regalado Bueno et al. Reference Regalado Bueno, San Emeterio, Ríos Garáizar, Gárate Maidagan, Marcos Gómez, Ugarte Cuetara, Líbano Silvestre, Medina-Alcaide, Moreno Larrazabal and Pérez Fernández2015) (photograph by Natxo Pedrosa).

This programme has also identified new funerary structures around these sites. The archaeological record, however, is poorly preserved. As the area today is heavily populated, many archaeological contexts have been altered substantially, or even destroyed, by urban development, roadworks or quarrying. Using remote-sensing prospection (LiDAR) combined with in situ verification, we have discovered new burial mounds in Munarriandi (Rios-Garaizar et al. Reference Rios-Garaizar, Tapia, Cubas, Libano, Trebolazabala, Aketxe, Vega and Garate2017) and Goikomendi (Figure 4), both situated adjacent to the River Butron. An integrated approach focused on both domestic and funerary archaeological sites, along with the excavation of these burial mounds, will allow us to investigate how different territories and landscapes were utilised during late prehistory.

Figure 4 Burial mound remote sensing. Munarriandi I: left) hillshade projection (Qgis-raster terrain analysis plugin, Z factor: 3.0, Azimut: 300º, vertical angle: 40º); top right) 3D view (Qgis2threejs plugin, vertical exaggeration: 3.0); bottom right) view of the burial mound (photograph by Joseba Rios-Garaizar).

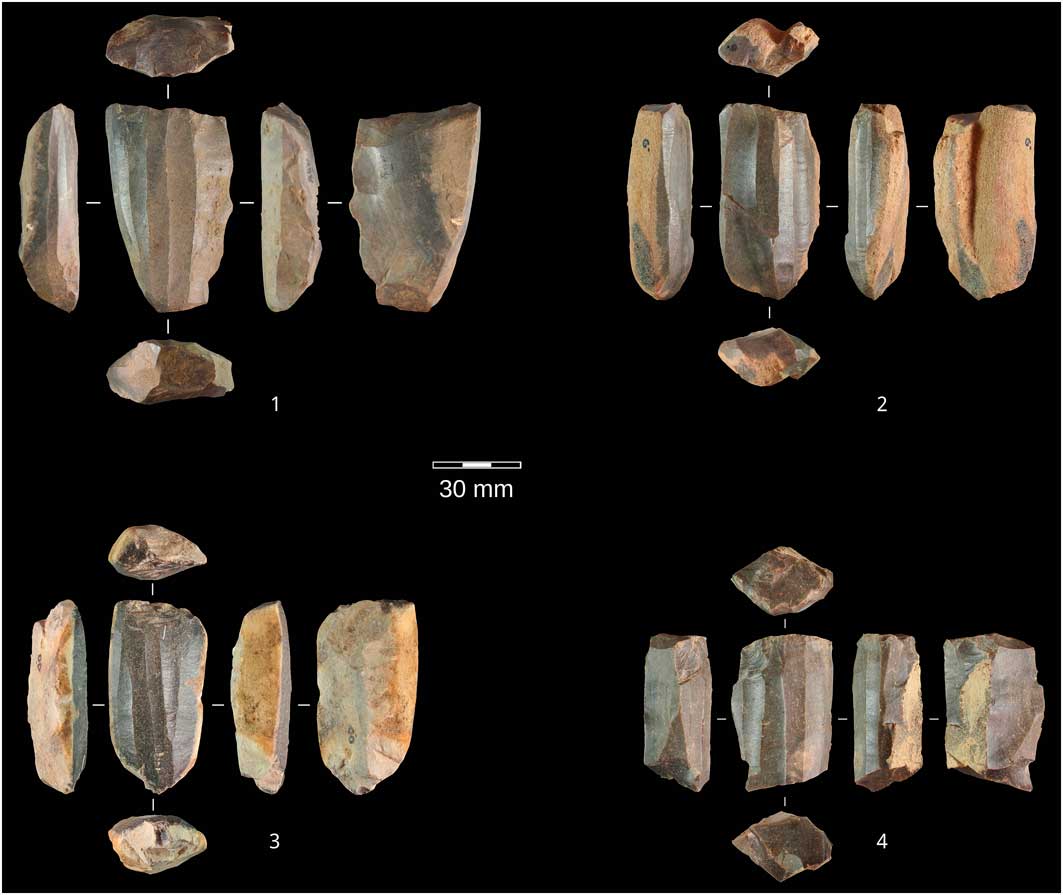

The richness of the lithic assemblage is probably influenced by the existence of a local, highly productive and long-exploited flint outcrop. Technological analyses focus on the classification of pressure-flaking cores for the production of blades. Currently, more than 200 pressure-flaking blade cores have been recorded throughout the area, most of which were intended for the production of relatively short, narrow and thin blades. Sites such as Meñakotz or Larrondo have produced large quantities of cores, suggesting the presence of blade-production workshops (Figure 5). Locally produced blades, however, are less frequently represented at these sites, suggesting that they were made for exportation.

Figure 5 Pressure-flaking blade cores from Larrondo (photographs by S. Vega-Lopez and I. Libano Silvente).

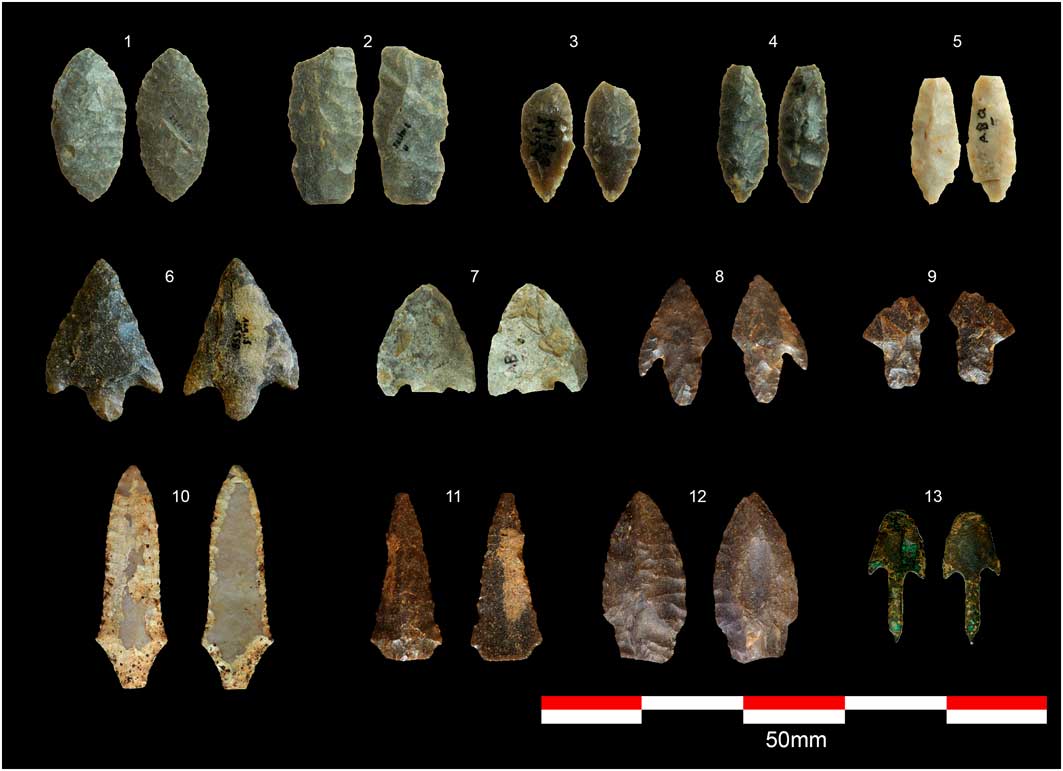

Similarly, bifacial arrowheads are typologically and technologically representative of late prehistory in northern Spain. Preliminary observations suggest a relatively simple production process, starting from simple cortical and thick flakes. Some of the points display diagnostic impact damage, while others seem to have been broken during production. Few of these points are made of non-local flint. Finally, different morphologies (Figure 6) suggest a wide chronology for these points, from the Late Neolithic to Bronze Age. Ceramics are rare at the aforementioned sites, and are limited to non-diagnostic sherds. Metal is also poorly represented, the most diagnostic artefact being a Palmela point (c. 3000 cal BC), recovered from a disturbed context in Kurtzia (Barandiarán et al. Reference Barandiarán, Aguirre and Grande1960) (Figure 6.13).

Figure 6 Arrowheads from Uribe Kosta. Bifacial points: 1–12; Palmela point: 13; from A. Aguirre collection (photographs by D. Garate Maidagan and J. Rios-Garaizar).

Preliminary data suggest that the establishment of farming communities in the Uribe Kosta region was clearly more complex than previously considered, with strong evidence for permanent settlements, specialised products and the symbolic transformation of the landscape. Our ongoing research will continue to: 1) identify and excavate new, well-preserved settlements and funerary monuments; 2) establish local chronologies, settlement patterns and environment interactions; and 3) analyse archaeological remains to evaluate the establishment of farming activities and the production of goods for exportation.