Introduction

Genetic evidence suggests that Thailand has been at the crossroads of human migration between Mainland and Island Southeast Asia from the Pleistocene to the present (Wangkumhang et al. Reference Wangkumhang, Shaw, Chaichoompu, Ngamphiw, Assawamakin, Nuinoon, Sripichai, Svasti, Fucharoen and Praphanphoj2013), with the northern Highlands of Thailand constituting one of the main migratory routes involving southern China (Sun et al. Reference Sun, Zhou, Huang, Lin, Shi, Yu, Liu, Chu and Yang2013). The original inhabitants of northern Thailand are understood to be the Lawa people, and evidence from autosomal STR loci (Kutanan et al. Reference Kutanan, Kampuansai, Colonna, Nakbunlung, Lertvicha, Seielstad, Bertorelle and Kangwanpong2011) shows that the Lawa of the north-western Highlands have the greatest genetic distance from other population groups within the region (i.e. the Khon Mueang, Mon, Shan, Lue, Khuen, Yan and Yong). Following recent large-scale genetic studies, there is a growing consensus that the people who first colonised and dominated Mainland and Island Southeast Asia are ancestral to extant Australo-Melanesian peoples, and that the composition of this founder population remained relatively stable until approximately 5000 years ago (Duggan & Stoneking Reference Duggan and Stoneking2014; Lipson et al. Reference Lipson, Loh, Patterson, Moorjani, Ko, Stoneking, Berger and Reich2014; Matsumura & Oxenham Reference Matsumura and Oxenham2014).

The Tham Lod rockshelter is a north-facing overhang located within the Pang Mapha District of the north-western Highlands of Thailand. Pang Mapha is a mountainous region (600–1700m asl), with a very distinctive karst topography. Pang Mapha has a low population density but high ethnic diversity; current residents include the Hmong, Karen, Red and Black Lahu, Shan and Thai peoples, as well as the Lawa (Shoocongdej 2006). Excavation of the Tham Lod rockshelter was commenced in 2002 by The Highlands Archaeology Project in Pang Mapha District (Shoocongdej 2003–Reference Shoocongdej2005, 2006, 2007). It is acknowledged as one of the oldest and most robustly dated sites to be excavated in Mainland Southeast Asia (Marwick Reference Marwick2008). The excavation revealed evidence of periodic human occupation from around 32380 years ago until the terminal Late Pleistocene (Khaokhiew Reference Khaokhiew2004; Shoocongdej 2007), although subsequent analysis of mussel shell (Margaritanopsis laosensis) recovered from the lowest excavation layer indicates that occupation may have commenced as early as 39960 years ago (Marwick & Gagan Reference Marwick and Gagan2011). The distribution of lithics, faunal remains and molluscs indicates that most of the human activity took place over a period of approximately 10000 years (25000–15000 BP), and that foraging was maintained as a subsistence strategy (Khlaewkhampud Reference Khlaewkhampud and Shoocongdej2003; Shoocongdej 2006, 2007; Wattanapituksakul Reference Wattanapituksakul2006; Amphansri Reference Amphansri2011; Chitkament et al. Reference Chitkament, Gaillard and Shoocongdej2015). Around 13500 years ago, possibly following a rock fall, the area became primarily used for human burials.

During April–August 2002, the skeletal remains (around 65 per cent complete) of a woman were recovered from Area 1, which is the excavation pit that abuts the north-facing cliff constituting the rockshelter overhang. The woman was found oriented on her left side in a flexed position. Across the radius and ulna lay a hammerstone, and above the burial was a circle consisting of five large pebbles and rounded limestone fragments. Sex and age at death were estimated as 25–35 years from the width of the greater sciatic notches of the pelvis, complete fusion of the epiphyses of the left radius and the complete eruption of the upper third molars (Pureepatpong Reference Pureepatpong, Bacus, Glover and Pigott2006). Using the height of the left radius, and a regression equation developed for Thai and Chinese populations (Sangvichien Reference Sangvichien1985), her height was estimated as 152±4cm. Accelerated Mass Spectrometry radiocarbon dating of the sediment located adjacent to the pelvis indicates that this individual lived 13640 (±80) years BP (14C dates are calibrated using OxCal 4.2 (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009) using the IntCal13 calibration curve (Reimer et al. Reference Reimer, Bard, Bayliss, Beck, Blackwell, Bronk Ramsey, Buck, Cheng, Edwards, Friedrich, Grootes, Guilderson, Haflidason, Hajdas, Hatté, Heaton, Hoffmann, Hogg, Hughen, Kaiser, Kromer, Manning, Niu, Reimer, Richards, Scott, Southon, Staff, Turney and van der Plicht2013), at 95.4% confidence). This makes this Tham Lod rockshelter individual the oldest human burial to be excavated in the north-western Highlands of Thailand, and probably a direct descendent of the founder population of Southeast Asia.

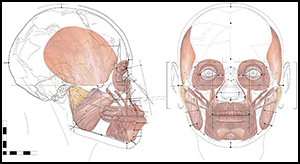

An estimation of the facial appearance of this Late Pleistocene woman was undertaken in 2015 using a suite of verified methods (see Figures 1–2 and online supplementary material (OSM)) often referred to as ‘facial approximation’. This estimation was primarily undertaken on account of the archaeological significance of the remains, but also because, as an individual who lived in the north-western Highlands of Thailand more than 13500 years ago, this woman constitutes a test of the methods used to estimate her face. Specifically, a test of the extent to which the methods retain aspects of the unique facial morphology of a woman who is neither recent nor European. As was clearly demonstrated by the problematic facial reconstruction of the 9000-year-old North American remains of ‘Kennewick Man’ (Holden Reference Holden1998), inappropriate population inflections have serious socio-cultural as well as scientific consequences.

Figure 1. Tham Lod estimation of facial soft tissue depths (fSTDs) and the facial features (eyes, nose, mouth, ears). Table 1 summarises research articles referenced to estimate the location, shape and size of the facial features. The online supplementary material (OSM) contains details of the methods used to estimate the face and a table of the fSTDs.

Figure 2. The completed Tham Lod facial approximation.

The face of ‘Kennewick Man’ was achieved through the application of the extraordinarily popular method of ‘(forensic) facial reconstruction’. Since 2002, nearly all of the recommendations associated with most, if not all, facial reconstructions have been proved invalid, but facial reconstruction continues nonetheless to be the technique of choice for nearly all forensic artists, anthropologists and palaeo-artists (for detailed methodological reviews, see Hayes et al. Reference Hayes, Sutikna and Morwood2013; Hayes Reference Hayes2014, 2016). Although the application of verified methods to estimate facial morphology is less subjective and more reliable than facial reconstruction, it is still the case that most of the verified methods applied in facial approximation have an inherent chronological and population bias. As can be seen in Table 1, the relationships used to estimate the facial appearance of this Late Pleistocene woman from Tham Lod are unavoidably derived from studies involving recent individuals, and furthermore, predominantly of European population affinity (15 European out of 27 populations).

Table 1. Population affinity associated with the facial approximation methods applied. Non-European populations are in bold type.

Some of the methods we applied to estimate facial appearance include the verification of their applicability to recent non-European populations, but many do not. Stephan and Simpson (Reference Stephan and Simpson2008) report no practical difference between the different population groups that comprise their large facial soft tissue depth (fSTD) dataset (the average number of individuals from which the weighted means have been derived is 3250). The differences in fSTD measurements within each population group from the total dataset are consistently larger than those between population groups, and, furthermore, the standard measurement error (where reported) is greater than the differences arising from population affinity, sex, adult ageing and body mass (Stephan & Simpson Reference Stephan and Simpson2008). Relative population neutrality is also reported for eyeball projection (Stephan Reference Stephan2002a), eyebrow position (Stephan 2002b), orientation of the mouth in relation to the mental foramen and lateral iris (Stephan 2003; Song et al. Reference Song, Kim, Paik, Han, Hu, Kim and Koh2007; Stephan & Murphy Reference Stephan and Murphy2008), and, by implication, the relationship between the malar tubercle and the exocanthion (Whitnall Reference Whitnall1911; Stephan & Davidson Reference Stephan and Davidson2008). Average interpupillary distance and average mouth widths have also been found to have no statistically significant difference between Australian European and Central/Southeast Asian populations (Stephan 2003). A study concerning lip height reports that Europeans display thinner lips (Wilkinson et al. Reference Wilkinson, Motwani and Chiang2003), and hence Indian subcontinent data from that study was applied to the woman from Tham Lod because of closer geographic proximity. The facial features that appear to be most dominated by findings derived from individuals of European population affinity are nasal projection and nasal dimensions (Rynn et al. Reference Rynn, Wilkinson and Peters2010), the position of the eyeball within the orbit (Stephan & Davidson Reference Stephan and Davidson2008; Stephan et al. Reference Stephan, Huang and Davidson2009; Guyomarc'h et al. Reference Guyomarc'h, Dutailly, Couture and Coqueugniot2012), the average diameters of the eyeball and iris (Driessen et al. Reference Driessen, Vuyk and Borgstein2011; Guyomarc'h et al. Reference Guyomarc'h, Dutailly, Couture and Coqueugniot2012) and the height of the ears (Farkas & Munro Reference Farkas and Munro1987).

The facial approximation of this Late Pleistocene woman is probably, therefore, influenced by the facial morphology of recent women, and European women in particular. In order to gauge the extent to which this inappropriate influence occurs, we undertook an anthropometric analysis that involved comparing our results with the average facial dimensions derived from 720 contemporary women living in 25 different countries and across three continents.

Materials and methods

The fSTD dataset used for this facial approximation is, as discussed above, comparatively population-neutral. To verify the extent of this neutrality with regard to Thailand, a subset of the Stephan and Simpson (Reference Stephan and Simpson2008) fSTDs that account for the same landmarks as fSTDs taken from 36 cadavers of Thai women (Puavaranukroh & Srettabunjong Reference Puavaranukroh and Srettabunjong2011) were compared. Significant differences are taken to be those that are greater than one standard error.

The dataset of ten anthropometric means used for our statistical comparison is from a single study (Farkas et al. Reference Farkas, Katic, Forrest, Alt, Bagic, Baltadjiev, Cunha, Cvicelová, Davies, Erasmus, Gillett-Netting, Hajnis, Kemkes-Grottenthaler, Khomyakova, Kumi, Kgamphe, Kayo-daigo, Le, Malinowski, Negasheva, Manolis, Ogetürk, Parvizrad, Rösing, Sahu, Sforza, Sivkov, Sultanova, Tomazo-Ravnik, Tóth, Uzun and Yahia2005). The age range of the women comprising this study (18–30 years) is of a comparable biological age to the Tham Lod remains (25–30 years), and the measures are the anthropometric means of 30 women per population group. The 25 population groups are from Europe, the Middle East, Africa, Asia and North America, although, as can be seen in Figure 3, the populations comprising this study are dominated by Western and Central Europeans. While the populations measured by Farkas and colleagues (2005) are somewhat eclectic, this research presents a comparatively robust international dataset of average facial measurements, with the same landmark definitions and methods to achieve the ten measurements applied throughout.

Figure 3. The comparative populations. The 25 international population groups (Farkas et al. Reference Farkas, Katic, Forrest, Alt, Bagic, Baltadjiev, Cunha, Cvicelová, Davies, Erasmus, Gillett-Netting, Hajnis, Kemkes-Grottenthaler, Khomyakova, Kumi, Kgamphe, Kayo-daigo, Le, Malinowski, Negasheva, Manolis, Ogetürk, Parvizrad, Rösing, Sahu, Sforza, Sivkov, Sultanova, Tomazo-Ravnik, Tóth, Uzun and Yahia2005) are shown shaded. The Thai village of Tham Lod is indicated by a black circle (northern Thailand). Map modified from unscaled ‘Simplified angular world map’, accessed under the Creative Commons licence CC0 1.0.

The Tham Lod facial approximation is derived from scaled orthogonal CT scans, which means that direct measurements are compatible with the in situ measurements from the living women in the Farkas study (Farkas et al. Reference Farkas, Katic, Forrest, Alt, Bagic, Baltadjiev, Cunha, Cvicelová, Davies, Erasmus, Gillett-Netting, Hajnis, Kemkes-Grottenthaler, Khomyakova, Kumi, Kgamphe, Kayo-daigo, Le, Malinowski, Negasheva, Manolis, Ogetürk, Parvizrad, Rösing, Sahu, Sforza, Sivkov, Sultanova, Tomazo-Ravnik, Tóth, Uzun and Yahia2005). The Tham Lod facial measurements were extracted from the soft tissue terminal landmarks of the relevant fSTDs, and from the landmarks used to estimate the internal facial features (Figure 1, Table S1 for the landmark definitions and fSTDs). The estimation of ear height was analysed separately using Pearson's correlation. The ten measurements covering the facial dimensions and dimensions of the internal features (eyes, nose, mouth) were entered into a cluster analysis by population group, and by facial feature, using Ward's Method with Euclidian distances; these were undertaken in tandem with principal components analyses (PCAs) and box plots. The ten measurements taken from the 25 extant population groups were first analysed independently of the Tham Lod facial approximation to note the overall pattern of clustering, and then analysed with the Tham Lod data to show indications of recent population inflection in the facial approximation. All analyses were accomplished using the statistical software PAST v.3.08 (Hammer et al. Reference Hammer, Harper and Ryan2001) with the cluster analyses and PCAs set to a bootstrap of 1000. The ten measures used in the analyses are listed, together with the Tham Lod facial approximation measurements and the means for each population, in Table S2 in the OSM.

Results

Comparison of the global, weighted fSTD means calculated by Stephan and Simpson (Reference Stephan and Simpson2008), with fSTDs taken from cadavers of Thai women (n = 36, Puavaranukroh & Srettabunjong Reference Puavaranukroh and Srettabunjong2011), is shown in Figure 4. The global dataset (Stephan & Simpson Reference Stephan and Simpson2008) displays greater tissue depths at all landmarks except for the zygion (the maximum width at the cheekbones), with the larger differences occurring predominantly along the cheeks and mid-face. Most of the global weighted means fall within one standard deviation of the Thai female mean (note that the Thai fSTD results do not report the standard error), with the exceptions being the nasion and philtrum.

Figure 4. Comparison of global weighted means with fSTD collected from 36 recent Thai female cadavers. The reported Thai standard deviations are indicated with dashed grey lines. The two datasets contain 15 homologous landmarks described in the OSM. The fSTDs applied in this facial approximation are indicated with an asterisk.

The relationship of ear height to lower face height (subnasale to menton) was sourced from an anthropometric study of 18-year-old North Americans (Farkas & Munro Reference Farkas and Munro1987). That relationship was, however, found to bear no correlation (Pearson's r = −0.15) with any of the international populations of women aged 18–30 years, including the North American women (Farkas et al. Reference Farkas, Katic, Forrest, Alt, Bagic, Baltadjiev, Cunha, Cvicelová, Davies, Erasmus, Gillett-Netting, Hajnis, Kemkes-Grottenthaler, Khomyakova, Kumi, Kgamphe, Kayo-daigo, Le, Malinowski, Negasheva, Manolis, Ogetürk, Parvizrad, Rösing, Sahu, Sforza, Sivkov, Sultanova, Tomazo-Ravnik, Tóth, Uzun and Yahia2005). Given that this inaccurate estimation of ear height could confound the multivariate analyses, it was not included as a comparative measure.

The analyses of the ten extant population measures (independently of the Tham Lod individual) result in Singaporean-Chinese, Vietnamese, Thai and Japanese women clustering separately from Indian women, and Zulu women clustering with African-American but not Angolan women. The Middle East populations do not cluster but are spread throughout, and the European women do not clearly cluster by population geography. PC1 (3 per cent variance) is weighted towards facial widths, and shows Japanese women to have the widest faces, followed by Thai, Vietnamese and Singaporean women. PC2 (22 per cent variance) is weighted towards eye spacing and facial height, and shows Indian women to have the widest-spaced eyes, relative to the other facial features, followed by Thai women. There is a relatively high variance in jaw width and inter-canthal width across the populations. Nasal dimensions tend to be dominated by relatively long and narrow noses, which is in keeping with the dataset containing a large number of European population groups.

When the facial measurements of the Tham Lod facial approximation are entered into the cluster analyses, the results indicate that this Late Pleistocene woman shares no close affiliation with any individual extant population, but is co-joined with a discrete cluster of Thai, Japanese, Singaporean-Chinese and Vietnamese women (see Figure 5). Examination of the PCAs (see Figure 6) shows that the main effect of including the Late Pleistocene woman from Tham Lod is to retain the East Asian/Southeast Asian grouping, but with the facial approximation falling at the extreme end of PC1 (46 per cent variance). PC1, as with the analysis undertaken without the Tham Lod facial approximation, is weighted towards facial widths, and, as indicated by the box plots according to facial measurements (see Figure S1), Tham Lod is an outlier in bizygomatic width. PC2 (18 per cent variance) is, as before, weighted towards eye spacing and facial height, with the facial approximation located close to the mean, and sharing this location with African-American, Bulgarian and Turkish women. PC3 (12 per cent variance) and PC4 (10 per cent variance) are less clearly separated by facial measures, but indicate a closer affinity between the Tham Lod facial approximation (which is again close to the mean of PC3) and extant modern women of North American, Azerbaijani, Greek and Polish population affinity, although still grouping loosely with Vietnamese and Singaporean-Chinese women.

Figure 5. Cluster analysis of all features using Ward's Method in PAST v.3.08 (Hammer et al. Reference Hammer, Harper and Ryan2001) of the Tham Lod facial approximation and 25 extant female populations (Farkas et al. Reference Farkas, Katic, Forrest, Alt, Bagic, Baltadjiev, Cunha, Cvicelová, Davies, Erasmus, Gillett-Netting, Hajnis, Kemkes-Grottenthaler, Khomyakova, Kumi, Kgamphe, Kayo-daigo, Le, Malinowski, Negasheva, Manolis, Ogetürk, Parvizrad, Rösing, Sahu, Sforza, Sivkov, Sultanova, Tomazo-Ravnik, Tóth, Uzun and Yahia2005).

Figure 6. Scatter plot of principal components analysis in PAST v.3.08 (Hammer et al. Reference Hammer, Harper and Ryan2001). The Tham Lod facial approximation is indicated by an arrow on the horizontal axis to the far right of the PC1 axis. The four East and Southeast Asian populations cluster (blue-coloured dots), and are indicated by an ellipse.

Figure 7 shows individual cluster analyses by specific facial features: the overall facial dimensions (bizygomatic width, bigonial width, facial height), eye spacing (outer and inner widths), nose (nasal width and height), and mouth width. In facial dimensions (Figure 7a), the Tham Lod facial approximation is affiliated with recent Japanese women, and this pairing is discrete from all of the other populations when only facial widths (bizygomatic and bigonial) are analysed. For eye dimensions (Figure 7b), the facial approximation is linked to Vietnamese women, and co-clusters with a pairing of Singaporean-Chinese and Angolan women. This double-paired cluster is retained when eye spacing, and not eye width, is entered into the analysis. Nasal dimensions (Figure 7c) result in the facial approximation being paired with Angolan women, and located within a discrete cluster containing Vietnamese women and a pairing of Thai and African-American women. Mouth width (Figure 7d) effectively separates the facial approximation and women of African population affinity from nearly all of the other populations, with the exception being that the facial approximation is paired with the mean of Hungarian women. In effect, the cluster analyses (the results of which are mirrored within parallel PCA) show the Tham Lod facial approximation to have a mix of East-Southeast Asian and African population attributes, with only one European population pairing (Hungary), the latter in terms of mouth width.

Figure 7. Cluster analysis using Ward's Method in PAST v.3.08 (Hammer et al. Reference Hammer, Harper and Ryan2001) of the facial features of the Tham Lod individual and the 25 populations measured by Farkas et al. (2005). a) Facial height and width; b) eye spacing; c) nose height and width; d) mouth width. For the key to population abbreviations, see Figure 5.

Discussion

Facial approximation differs from most, if not all, facial reconstructions when it involves applying verified skull to soft tissue relationships to estimate facial appearance. Although many of these verified relationships have involved studies of non-European populations, it is still the case that European craniofacial relationships predominate, and all have, of necessity, been derived from recent human populations (Table 1). Studies that have been tested for relative population neutrality include the global weighted means of fSTDs (Stephan & Simpson Reference Stephan and Simpson2008) and estimation of mouth width (e.g. Stephan 2003; Song et al. Reference Song, Kim, Paik, Han, Hu, Kim and Koh2007; Stephan & Murphy Reference Stephan and Murphy2008). Estimations of the shape and projection of the nose, the position of the eyeball within the orbit, and the average diameters of the eyeball and iris have not been tested, and are more likely to inflect a facial approximation with European characteristics.

Late Pleistocene skulls have been found to display larger jaws (e.g. Velemínská et al. Reference Velemínská, Brůžek, Velemínský, Bigoni, Šefčáková and Katina2008) and bigger teeth (e.g. Brace et al. Reference Brace, Rosenberg and Hunt1987) than Late Holocene skulls, and the craniofacial measurements of Late Pleistocene skulls from Africa, East Asia and Europe are mostly, on average, larger than the average craniofacial dimensions displayed by recent humans (Curnoe et al. Reference Curnoe, Ji, Herries, Bai, Taçon, Bao, Fink, Zhu, Hellstrom, Luo, Cassis, Su, Wroe, Hong, Parr, Huang and Rogers2012). Late Pleistocene crania have also been found to show a high level of intragroup diversity compared to recent crania (Harvati Reference Harvati2009), probably related to the limited number of individuals available for study, and the poor preservation characteristic of the comparatively few Late Pleistocene individuals excavated to date. Nevertheless, if the facial approximation methods we applied were able to retain the distinguishing Late Pleistocene characteristic of skull robusticity, then facial widths will distinguish our facial approximation most clearly from modern populations. The results of the analyses indicate that our Tham Lod facial approximation is an outlier in bizygomatic width. In all other facial dimensions, however, the facial approximation groups with the mean anthropometric data taken from recent women, but not recent women of European population affinity.

In essence, this comparative analysis involving the mean variation of extant modern women from 25 different population groups indicates that our facial approximation of Tham Lod is not overly influenced by European facial characteristics. Instead, when all facial dimensions are analysed together, the facial approximation is discrete from all populations, shows closest affiliation with recent women from East and Southeast Asia, and is most closely affiliated (albeit at a distance) with Japanese women in facial width and height. Analyses of the individual facial features—eyes, nose and mouth—indicate that the Tham Lod facial approximation shares morphological similarities with women of African population affinity, particularly in the dimensions of the nose and mouth. Other than a clustering with extant modern Hungarian women with regard to mouth width, European women, despite dominating both the comparative population study and the methods used to estimate facial appearance, are noticeably absent.

Conclusion

Due to her chronology, this Late Pleistocene woman is most likely to be ancestral to the people who first colonised and dominated Mainland and Island Southeast Asia until approximately 5000 years ago (Duggan & Stoneking Reference Duggan and Stoneking2014; Lipson et al. Reference Lipson, Loh, Patterson, Moorjani, Ko, Stoneking, Berger and Reich2014; Matsumura & Oxenham Reference Matsumura and Oxenham2014). Given that this woman is not European and not from the Late Holocene, the relationships we applied to estimate her face are inappropriate. We therefore anticipated that the results of our facial approximation would be indistinguishable from recent populations, and that the face would most likely group with recent European facial dimensions. Instead, when we compared our facial approximation to the mean facial measurements of extant modern women from 25 populations spanning the globe, our estimated facial appearance was shown to be distinct from women of today at a global level, being generally more robust in facial width. Furthermore, while the estimated facial features (eyes, nose and mouth) share morphological similarities with recent women, these are almost exclusively women of East Asian, Southeast Asian and African population affinities. These results indicate that there is some population neutrality in the facial approximation methods we applied, although these results need to be seen as indicative rather than conclusive.

As noted earlier, the anthropometric means of recent women (Farkas et al. Reference Farkas, Katic, Forrest, Alt, Bagic, Baltadjiev, Cunha, Cvicelová, Davies, Erasmus, Gillett-Netting, Hajnis, Kemkes-Grottenthaler, Khomyakova, Kumi, Kgamphe, Kayo-daigo, Le, Malinowski, Negasheva, Manolis, Ogetürk, Parvizrad, Rösing, Sahu, Sforza, Sivkov, Sultanova, Tomazo-Ravnik, Tóth, Uzun and Yahia2005) are population eclectic. The populations included in the study by Farkas and colleagues are not representative of the extant human population diversities of Europe, the Middle East, Asia, Africa and North America (cf. Figure 4). In addition, the facial measurements we analysed do not fully encapsulate facial variation and, as indicated by the multivariate analyses, do not clearly distinguish between extant populations from quite distinct geographic regions. Therefore, while our facial approximation of the Tham Lod individual is clearly distinguished from women of European population affinity, the apparent inflection in our facial approximation of East Asian, Southeast Asian and African facial morphologies needs to be treated with caution. Further research with a more representative global dataset and more facial means may produce more nuanced, and perhaps different, results.

What is suggested by this study is that the methods we applied appear to be appropriate for estimating the face of non-European past peoples. Although these research methods are dominated by relationships derived from recent European skulls and faces, our estimation of the face of a Late Pleistocene woman from the Tham Lod Rockshelter in the north-western Highlands of Thailand is neither overtly recent, nor overtly European. Therefore, it seems likely that at least some of the methods we applied to estimate the face are shaped by, and retain, aspects of an individual's unique craniofacial morphology and location within the archaeological record.

Acknowledgements

This research project was made possible by the support of a number of grants and the collaboration and assistance of many institutions, including the Tham Lod Wildlife Sanctuary of National Park, Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment, Thailand; Fine Arts Department; Ministry of Culture, Thailand; Department of Archaeology, Silpakorn University. Financial support for the Highland Archaeology Project in Pang Mapha phases one and two (HAPP) was provided by the Thailand Research Fund (TRF) from 2001–2006. The Archaeological Heritage Management at Tham Lod and Ban Rai rockshelters project was supported by the US Ambassador Grant 2006 from 2006–2007. The Archaeological Exploration and Heritage Management in Pai-Pang Mapha-Khun Yuan District in Mae Hong Son Province, project phases one to three (PPK) was supported by the TRF from 2007–2012, and The Interaction between Humans and their Environments in Highland Pang Mapha, Mae Hong Son Province Project (IHE) is supported by the TRF (2013–2016). A debt of gratitude is owed to the local people at Ban Rai and Tham Lod villages. We thank the HAPP, PPK and IHE project teams for their support over many years, and in particular we would like to thank for their help and support the future faces of Thai archaeology: Siriluck Kanthasri, Chonchanok Samrit, Somthawin Sukliang and Wokanya Na Nongkhai. Finally, we thank the two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and recommendations.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2017.18