Introduction

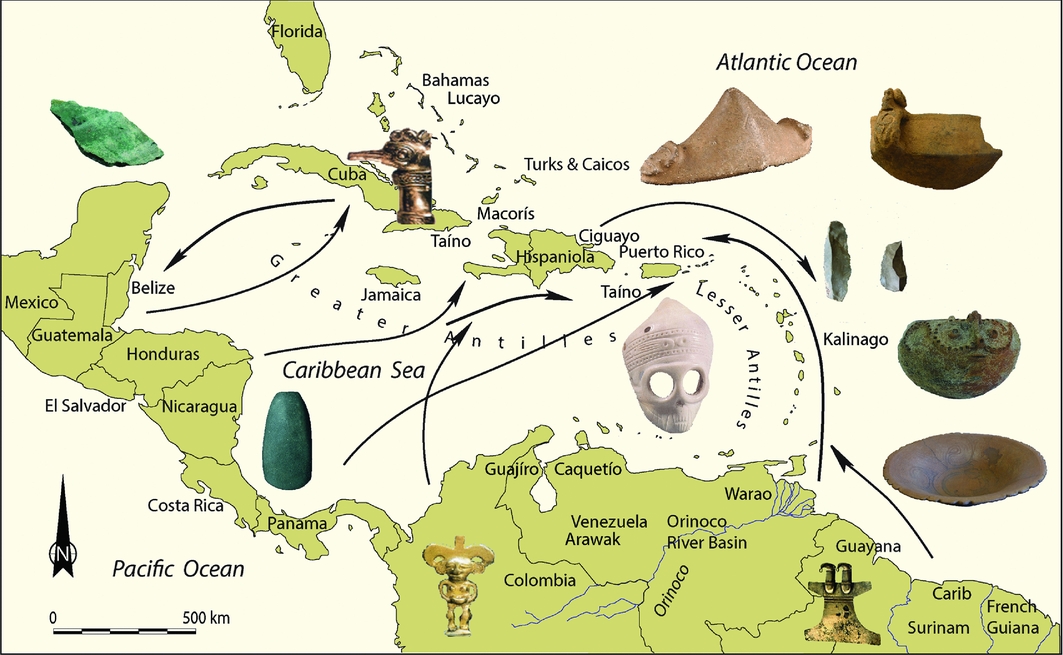

The Spanish conquest of the Americas represents a landmark in global history. The indigenous Caribbean, the first area that was affected by this process, was suddenly and dramatically transformed. Upon Columbus's arrival in the New World, the islands between Cuba and Aruba were inhabited by indigenous societies, now popularly known as Caquetío, Carib and Taíno (Keegan & Hofman Reference Keegan and Hofman2017), whose ancestors had entered the archipelago from different parts of South and Central America around 6000 BC. By AD 1000, culturally diverse island societies had developed, and by 1492, a web of interlocking networks had spread across the Caribbean Sea, crossing local, regional and pan-Caribbean boundaries (Figure 1; Hofman et al. Reference Hofman, Mol, Hoogland and Valcárcel Rojas2014) that the Spanish undoubtedly used to disperse rapidly throughout the region. The initial European explorations of the insular territories were followed by the founding of the Spanish settlements of La Navidad (1492) and La Isabela (1493) on the north coast of ‘La Española’ (Hispaniola), setting the stage for the European colonisation of the Americas (Deagan & Cruxent Reference Deagan and Cruxent2002; Delle et al. Reference Delle, Hauser and Armstrong2011). Within 20 years, indigenous peoples were reported to be either killed, enslaved or converted and incorporated into the encomienda system, an economic model based on both indigenous and Castilian socio-political institutions (Arranz Márquez Reference Arranz Márquez1991; Esteban Deive Reference Esteban Deive1995; Ulloa Hung & Valcárcel Rojas Reference Ulloa Hung and Valcárcel2016).

Figure 1. Map of the Caribbean showing pre-colonial networks with examples of the types of artefacts being exchanged. (Map by Corinne Hofman and Menno Hoogland.)

Initially, in their quest for precious metals and the necessary labour to acquire these, the Spanish Crown enslaved and transported indigenous populations of the surrounding regions to the Greater Antilles. From 1508 and 1509, the Spanish Crown authorised the entry of indigenous peoples from other islands to Hispaniola as naborias, or free labourers and slaves. By royal decree, slave hunting was legalised on the smaller islands of the Lesser Antilles, and other islands such as the Bahamas from 1503 onward (Marte Reference Marte1981: 70–72; Mira Caballos Reference Mira Caballos1999). Despite the effects of slave raiding, the Lesser Antilles became refuges for Amerindians who sometimes served as ‘middlemen’ in trade between the Spanish Caribbean and continental South America. Indigenous resistance, European colonisation and the influx of enslaved Africans, beginning in the sixteenth century, led to the mixing of biological ancestries and the formation of new identities and social and material worlds (Deagan Reference Deagan2003; Cooper et al. Reference Cooper, Samson, Nieves, Lace, Caamaño-Dones, Cartwright, Kambesis and Olmo Frese2016; Ulloa Hung & Valcárcel Rojas Reference Ulloa Hung and Valcárcel2016). These processes eventually contributed to the formation of present-day, multi-ethnic Caribbean society.

In addition to a rich indigenous archaeological record, Amerindian biological inheritance is clearly apparent amongst Caribbean-descendant communities (Moreno-Estrada et al. Reference Moreno-Estrada, Gravel, Zakharia, McCauley, Byrnes, Gignoux, Otiz-Tello, Martínez, Hedges, Morris, Eng, Sandoval and Bustamante2013), and aspects of cultural continuity are evident through contemporary oral traditions and other cultural and religious practices. Despite this, indigenous Caribbean contributions have been disregarded in contemporary discourse and global history. A lack of indigenous written sources means that perceptions of the effects of Columbus's 1492 colonisation on indigenous Caribbean populations have tended to focus exclusively on European accounts. Regardless of research on colonial encounters worldwide, inspired by the quincentennial Columbus celebrations (e.g. Zimmerman Reference Zimmerman1994; Stein Reference Stein2005), as well as the scholarly advances made in deconstructing the documentary bias and European and colonial preconceptions (e.g. Hulme Reference Hulme1986; Sued Badillo Reference Sued Badillo2001; Deagan Reference Deagan2003; Curet Reference Curet2006; Anderson-Cordova Reference Anderson-Cordova2017), the Caribbean indigenous past remains marginalised in colonial and post-colonial historiographies, and in traditional narratives of the colonisation of the Americas in general (Ulloa Hung & Valcárcel Rojas Reference Ulloa Hung and Valcárcel2016).

In this article, we redress this imbalance by presenting the initial results of recent investigations in northern Hispaniola, one of the first regions where the interactions between the Old and New Worlds took place. Based on a rereading of the main documentary sources, new archaeological data and a study of contemporary regional cultural traditions, we aim to provide an alternative perspective of the indigenous socio-cultural landscape as experienced by Europeans upon their arrival, and emphasise the survival of indigenous legacies in the area.

An early colonial perception of the northern Hispaniolan landscape

Northern Hispaniola (part of the present-day Haiti and the Dominican Republic) includes the Cordillera Septentrional, Cordillera Central, Massif du Nord and Cibao Valley. The area consists of mangroves, swamps, savannahs, beaches, high mountains and river floodplains that stretch for kilometres. The Cibao Valley and the floodplains of the River Yaque constitute a large flat area separating the main mountain systems of the north of the island, the Cordillera Septentrional and the Cordillera Central. The Cordillera Septentrional is separated from the Atlantic Ocean by the so-called Atlantic Corridor. The landscape in the northern part is hilly, while the southern part is flat and covered by alluvial deposits from rivers, among them the Camú, Bahabonico and Yaque. The Cordillera Septentrional extends for more than 200km, with lower hills at its edges and taller peaks in its central zone. This is a strip between the coastal corridor and the interior plain that divides the Western and Eastern Cibao Valley. In northern Haiti, the Massif du Nord is an extension of the Cordillera Central of the Dominican Republic, which spreads to the north-western peninsula. The north-central sector of Hispaniola includes the provinces of Montecristi, Puerto Plata and Valverde in the Dominican Republic, and the Département du Nord in Haiti. Despite being close together, their geography, topography and vegetation are rather different. Colonial and recent landscape transformation has dramatically altered the original setting.

Northern Hispaniola was the first area of the Americas where extensive confrontations between Amerindians and Europeans took place following Columbus's landing on Guanahní (supposedly San Salvador), on 12 October 1492, and subsequent incursions into Cuba. It is from this area that the Spanish first entered the interior of Hispaniola in 1494, experimented with European crops and cattle by taking advantage of indigenous networks and knowledge, and began subjugating indigenous people through slavery while conquering the American continent. The region was initially described by Columbus in 1492 when he founded La Navidad. This earliest permanent settlement of the Spanish Empire was in the ‘chiefdom polity’, or cacicazgo, of Marien, under control of cacique Guacanagarí (Deagan Reference Deagan2004). It was also in 1492 that Columbus named Montecristi, a mountain east of La Navidad, used by him and others as a sailing landmark (Ortega Reference Ortega1987: 21–22). He encountered people canoeing near the coast and described a densely populated area. In the surrounding area, Columbus surveyed the Yaque River and was taught by the Amerindians that travelling upstream led to the area called Cibao.

During the second voyage, after establishing La Isabela, the Spanish began an extensive exploration of the interiors of Hispaniola (Deagan & Cruxent Reference Deagan and Cruxent2002). Columbus requested to survey the entire island, locate its position and dimensions, and collect information to be sent to Spain (León Guerrero Reference León Guerrero2000: 265). Simultaneously, the initial explorations from La Isabela to the Cibao Valley began on 6 January 1494 (Las Casas Reference Las Casas1875: volume 2, 25–26) and revealed the existence of indigenous roads or paths that allowed access to the ascent of the Cordillera Septentrional, to the hospitality of most of the communities and to the gold in the region. Following this, Columbus sent a memorandum to the Spanish court on 2 February 1494, along with gold samples found in the Cibao Valley, plants and other interesting things discovered on the island (Columbus Reference Columbus and Balaguer1988).

On 12 March 1494, Columbus personally made his first incursion into the Cibao, marking a new stage in the relationship with the indigenous communities. This trip, organised as a demonstration of power, included around 400 men and cavalry. In addition to establishing a colonial road into the Cibao, the first Spanish fort (Santo Tomás) was constructed to control the Amerindians and extract gold. In April 1494, Columbus sent a new army to Santo Tomás with clear instructions to cross the island, to ‘pacify’ it, to explore regions that were not yet known and to take possession of these in the name of the Spanish Crown (León Guerrero Reference León Guerrero2000: 315–18). Along the route from La Isabela to Santo Tomás, currently known as the Ruta de Colón, the forts of La Magdalena, La Esperanza and La Catalina were built next to the Yaque River (Las Casas Reference Las Casas1875: volume 2, 120–22; Arrom Reference Arrom and Arrom1990). These forts, along with others, were constructed for the collection of taxes and tributes, and to exercise dominance. The first expeditions to the Cibao promoted and intensified the exchange of goods between indigenous peoples and Europeans (Columbus Reference Columbus and Balaguer1988), and it was through these experiences that the Spaniards began to consume local foods and supplies due to the scarcity of those brought from Europe. Later, this region was used to test the system of poblamiento (settlements) and Castilian colonisation. Through repartimientos and encomiendas (forced labour systems), lands were seized and redistributed, and indigenous peoples were dispersed across different towns and regions, in a process that saw the initial developments of urbanisation. The latter created a nuclei of indigenous communities associated with the exploitation of important resources (Arranz Márquez Reference Arranz Márquez1991: 63–64).

European documents display the area as a space of conflicts, both amongst Europeans, and between colonisers and indigenous peoples, in addition to being a slave-supplying region linked with Columbian commerce (Esteban Deive Reference Esteban Deive1995: 58–63). From that point of view, the documents not only reflect the curiosity or surprise of the European colonisers, but also assessments of the economic or strategic value of, among other things, plant species, animals, watercourses and, especially, gold. Another important factor in the initial colonial perception of the regional landscape was the indigenous peoples themselves, where descriptions refer not only to their physical appearance, dress or adornment, but also to their attitudes towards Europeans (hostile or friendly), which contributed to the creation of a dichotomous image about them. This historical perception permeated the cultural and intellectual reference of the European chroniclers, and has been fundamental in generating a preconceived image of indigenous societies.

The first exchanges between Europeans and indigenous peoples included gold ornaments, fish, cassava, water, cotton and exotic birds. In return, they received glass beads, bells, caps, pieces of broken bowls, fragments of glass cups, brass rattles, laces, pins, canvas shirts, coloured cloths, scissors and knives, which were of little value. These exchanges were viewed by the Europeans as mechanisms to establish alliances with indigenous caciques, besides obtaining their favours, geographic information on the presence of gold and generating a favourable image for the communities that they encountered or would go on to encounter (Las Casas Reference Las Casas1875: volume 1, 306–25).

An indigenous archaeology of northern Hispaniola and the Ruta de Colón

Archaeological prospections were initiated in the Dominican part of the region in the 1980s (e.g. Guerrero & Veloz Maggiolo Reference Guerrero and Veloz Maggiolo1988). This work formed the basis for the surveys in the Puerto Plata province, conducted between 2007 and 2012 (Ulloa Hung Reference Ulloa Hung2014). The area of Montecristi was previously only occasionally explored, and no substantial publications have been made available. In northern Haiti, archaeological research began in the 1930s (Rouse Reference Rouse1941), reaching a peak in the 1980s, and mostly focused on the areas of La Navidad (site of En Bas Saline) and the Spanish town of Puerto Real (Deagan Reference Deagan2003, Reference Deagan2004; see also Moore & Tremmel Reference Moore and Tremmel1997).

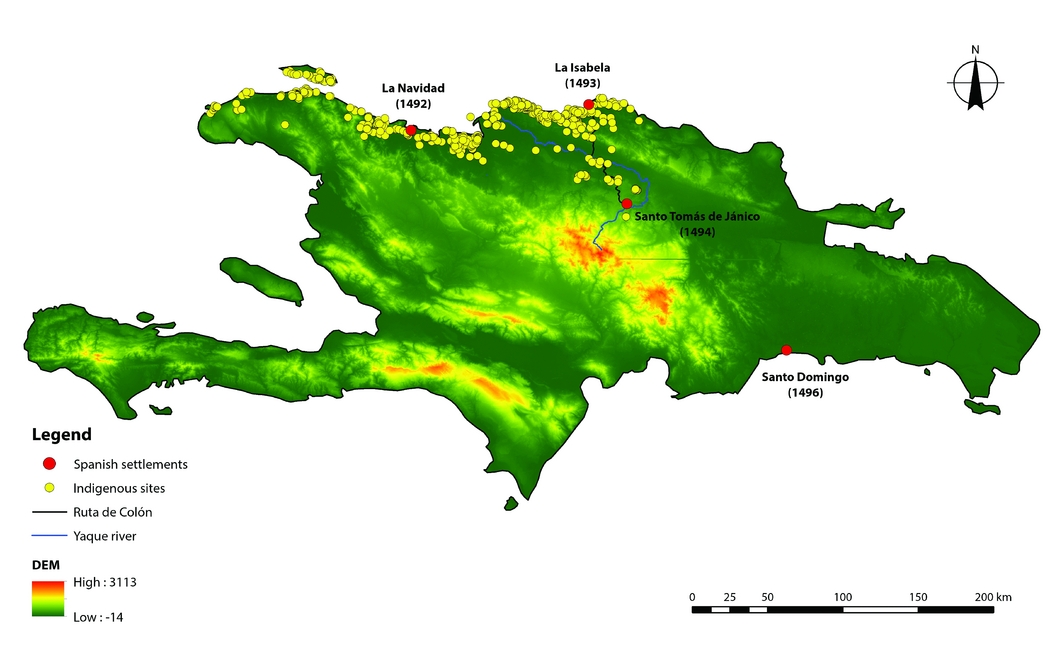

The provinces of Puerto Plata, Valverde, Montecristi and around Fort Liberté in Haiti were surveyed between 2013 and 2017. More than 300 archaeological sites were recorded in an area covering approximately 4300km2 (Figure 2) (Ulloa Hung & Herrera Malatesta Reference Ulloa Hung and Malatesta2015). In addition, open-area excavations were conducted at three Amerindian sites: La Luperona, El Flaco and El Carril (Hofman et al. Reference Hofman, Ulloa Hung and Hoogland2016), all located in the Cordillera Septentrional, near the Paso de los Hidalgos, the mountain pass that Columbus crossed in 1494 on his way from the coast to the Cibao Valley.

Figure 2. Map of Hispaniola showing approximately 300 recorded indigenous sites from the north of the island relative to the Ruta de Colón. (Map by Eduardo Herrera Malatesta; DEM download from https://gdex.cr.usgs.gov/gdex; ASTER GDEM is a product of NASA and METI.)

More than 300 indigenous settlements

Surveys were conducted along the north-western Hispaniolan coast, from Puerto Plata in the east, to Fort Liberté in the west, and towards the interiors up to Valverde (Mao) and Jánico. While the visibility of artefacts on the surface was not always evident, some settlements stood out because of their characteristic topography of mounds and earthworks alternating with levelled areas. This particular topography presented a unique opportunity to investigate settlement patterns, spatial organisation and dynamics through novel non-destructive remote-sensing techniques (Sonnemann et al. Reference Sonnemann, Ulloa Hung and Hofman2016) (Figure 3). More than 300 sites, radiocarbon dated to AD 800–1500 (Figure 4), were documented, reflecting inter-community interaction through mixtures of ceramic styles (Ostionoid, Meillacoid and Chicoid) (Figure 5). These admixtures were probably linked to mechanisms of competition and exchange, and to access to resources of different environmental spaces within the region (Ulloa Hung Reference Ulloa Hung2014).

Figure 3. DEM image based on drone photogrammetry and topographic mapping of mounds and levelled areas at the site of El Carril (map by Till Sonnemann and Sven Ransijn for NEXUS1492).

Figure 4. Selection of radiocarbon dates for northern Hispaniola, restricted to the thirteenth to fifteenth centuries, calibrated using CALIB 7.0.4; (68.2% confidence (black) and 95.4% confidence (white)). Sources: dates for Hatilo Palma are taken from Veloz Maggiolo et al. (Reference Veloz Maggiolo, Ortega and Caba Fuentes1981); dates for En Bas Saline from Deagan (Reference Deagan2004); all other dates are from Ulloa Hung (Reference Ulloa Hung2014) except for Los Indios and El Flaco, which are previously unpublished dates. (Figure by Menno Hoogland.)

Figure 5. Ceramic styles of northern Haiti and the Dominican Republic: a) Chicoid series (AD 1200–1500), with incised lines and dots, scrolls and anthropo-zoomorphic representations; b) Meillacoid series (AD 900–1500), with incised cross-hatched designs, appliquéd fillets and zoomorphic modelling; c) Ostionoid series (AD 800–900), with thin red slipped pottery, ‘d-shaped’ handles and modelled zoomorphic designs. Stylistic and technological features of these different styles are combined during transitional phases. (Photographs by Corinne Hofman and Menno Hoogland.)

In the provinces of Puerto Plata and Valverde, the regional cultural landscape is characterised by: rockshelters or caves that served as shelters or rooms located near the seashore; linear scatters of shells created by economic activities in places close to marshes and mangroves; and by sites in open spaces that are concentrated on the mountain summits and plateaus of the Cordillera Central and Septentrional, as well as in the valleys and floodplains of important rivers, such as the Amina, Mao, Yaque, Canas, Bahabonico and Unijica (Figure 6a & b). These rivers have indigenous toponyms, and some are mentioned in historical descriptions of the conquest. These sites are located at elevations ranging between 50–700m asl, which directly relate to their distances from the ocean and which fluctuate from >0.5–40km. Both elevation and distance to the sea seem to be important factors for settlement choice, often combined with proximity to streams and rivers, and inter-visibility between the sites (Ulloa Hung & de Ruiter Reference Ulloa Hung and de Ruiter2011). The visual domain of the sea and the Cibao Valley was probably a strategic priority for the location of settlements, as well as for the management and control of the landscape. This is evidenced by the existence of site clusters, including smaller and larger sites of all types.

Figure 6. Sites in diverse geomorphological landscapes, Dominican Republic: a) site on Cordillera Septentrional; b) example of a cave site. Haiti: c) eroded site exposed at Fort Liberté; d) shell and ceramic materials on the surface at Fort Liberté. (Photographs by Jorge Ulloa Hung and Joseph Sony Jean.)

The sites with the highest incidence of stylistic co-occurrence are generally located in the passage or connection of two or more landscapes (e.g. mountain-valley, valley-coast, mountain-valley-coast). These settlements have a size of 17000–40000m2. In addition, their particular location stands out within the clusters of sites, suggesting that these probably constituted nodes or important strategic spaces in a social and political network. Other, smaller sites of 5000–12000m2 are located in the surroundings of these strategic nodes, and might have constituted places for specific activities. Together, these were part of an extensive settlement system that connected different areas of activity within the region, and helped structure different social bonds throughout the community. In the Montecristi province, there also exists a clear correlation between site size and location. Larger sites are situated in the inter-montane valleys of the Cordillera Septentrional, or on the floodplains close to the Yaque River. Smaller sites are generally on the top of hills, and have better visibility of the surrounding landscape. Specialised sites related to the exploitation of sea resources are located along the coast, close to the mangroves and natural salt concentrations.

Forty-three of the sites in the Puerto Plata/Valverde provinces are characterised by a landscape of anthropogenic mounds surrounding levelled areas interpreted as part of the management of living spaces or habitation areas. Such sites are also present in the northern sector of the Montecristi province, east of the Morro de Monte Cristi (Ulloa Hung & Herrera Malatesta 2015; Sonnemann et al. Reference Sonnemann, Ulloa Hung and Hofman2016). The construction of mounds is associated with the Meillacoid and Chicoid cultural traditions in this part of Hispaniola, and has been found at sites located with different geomorphological settings and elevations. The mounds and levelled areas are found at small- and medium-sized sites that are strategically located on steep ridges or hillsides, probably to indicate territorial control or act as some other visual promontory. These are, however, also recorded at sites with a relatively flat relief and no limitations of natural barriers.

In the Fort-Liberté region, coastal sites are mostly associated with Meillacoid and Chicoid ceramics. Some of the sites are characterised by small shell middens, while others are very large circular mounds associated with different types of material culture and remains. Rivers, lagoons and coastal plains were crucial for the development of Amerindian settlementbecause of the quick access to natural resources (Figure 6c & d). Only in some occasions were settlements established in dry sectors, far away from rivers. Over the course of the pre-colonial occupation, settlements increased in the Fort Liberté region, and the bay was probably a pivotal location for social interaction and exchange on a micro-regional level for the communities living on the small offshore islands, in the coastal areas and in the interior of the island.

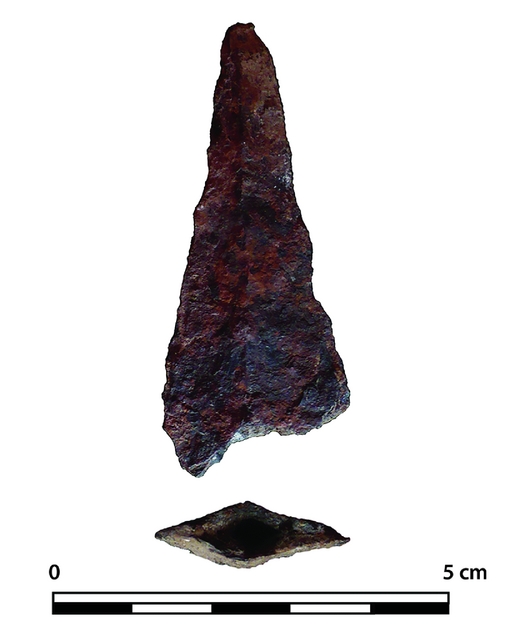

Curiously, little to no evidence of Spanish materials was revealed by the survey, although some sites are clearly dated within the time frame of the first encounters. A sole Spanish metal arrow point has been recovered from the site of Los Balatases in the Puerto Plata province, located at an elevation of 270m asl, and 9.5km east from the Spanish settlement of La Isabela (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Spanish metal arrow point recovered from the site of Los Balatases in the province of Puerto Plata. (Photograph by Jorge Ulloa Hung.)

Open-area excavations in the Cordillera Septentrional

Of the three excavated sites, El Flaco is the best-researched today. The site is located in the southern foothills of the Cordillera Septentrional in Loma de Guayacanes (province of Valverde), at an elevation of 300m asl. The settlement is situated near El Mirador de Colón, in the mountains from which Columbus first spotted the Cibao Valley on his way from the coast. El Flaco is situated in a transitional geomorphic zone between the Cordillera and Cibao Valley, approximately 20km from La Isabela, 2km from El Carril and 8km from La Luperona. Drone flights, topographic mapping and open-area excavations (1256m2) have revealed an organised series of mounds surrounding levelled areas with house structures (Figure 8) (Hofman & Hoogland Reference Hofman and Hoogland2015; Sonnemann et al. Reference Sonnemann, Ulloa Hung and Hofman2016).

Figure 8. Aerial view of the excavations at El Flaco with the circular layout of a house visible on one of the levelled areas. (Drone image by Till Sonnemann for NEXUS1492.)

Archaeological evidence suggests that both domestic and ritual activities took place on the mounds. There are also several earthen walls connecting the mounds, constructed for the delineation of the habitation area, but perhaps also as markers of ancestral space. In order to flatten areas for the building of houses and auxiliary structures, the underlying limestone had to be levelled. Two large house structures (9m in diameter) composed of two circular rows of postholes, as well as a number of small round huts (3–4m in diameter) with fireplaces and hearths, were excavated. Other posts and stakes belong to shelters, drying racks, cages and other auxiliary structures. A large number of hearths were found surrounding the houses or deposited within the mounds. These hearths were composed of fire-cracked stones with large amounts of ceramic and stone griddles. The stratigraphy of the mounds, with layers of brown or black soil alternated with layers of ash and garbage, reflect their use for various household activities over time, such as kitchen gardens (Figure 9). Layers of white limestone and rocks intersect the layers of ash and soil. The white limestone represents the soil that was removed from the house areas to create the levelled areas.

Figure 9. Stratigraphic profile of the south wall of unit 75 in a mound at El Flaco. The various layers and lenses (1–14) represent different deposition episodes and functional stages of the mound. From bottom to top: 1) weathered calcareous bedrock (90 per cent stones and gravel) in a silt matrix; 2) palaeosol; 3) refuse layer composed of land snails, ceramics and ash; 4) deposition of material from layer 1; 5) deposition of soil from levelled bedrock; 6) same as 3 but finer; 7) same as 5 but finer; 8) ash deposit; 9) same as 3 but finer; 10) ash deposit; 11) refuse deposit; 12) deposition of soil from levelled bedrock; 13) ashy refuse layer; 14) topsoil. (Image by Menno Hoogland.)

Human and dog burials were encountered in the mounds in layers of limestone and ash, reflecting the recurrent use of the mounds as ancestral spaces, perhaps as a parallel to the house-floor burials encountered in other sites in the Caribbean (e.g. Hoogland & Hofman Reference Hoogland and Hofman1999). Burials include infants, sub-adults and adult individuals, and date from between AD 1250 and 1490 (Hofman & Hoogland Reference Hofman and Hoogland2015). A variety of tools, beads, pendants and other artefacts made of shell, human and animal bones, and both locally sourced/made and imported lithics and ceramics were recovered from the mounds and the sweeping areas surrounding the houses on the levelled locations. The main occupation of the site dates between the thirteenth and fifteenth centuries, and is characterised by Chicoid ceramics. This was clearly the main period of occupation and the setting in which the indigenous inhabitants were confronted with the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors in the area. The final radiocarbon date of AD 1490, obtained from one of the burials, strongly suggests quasi-contemporaneity with the passage of Columbus through the Cordillera Septentrional. Material evidence for an actual encounter is, however, lacking.

Indigenous legacies today

The archaeological data suggest that the indigenous socio-cultural landscape along the route followed by Columbus in 1494 was characterised by connection and interaction. The creation of this route was not exactly Columbian, but the conversion, transformation and adaptation of an indigenous trail to colonial purposes became an important axis for the exploration, domination and economic and military control of the interior of Hispaniola, especially Cibao. The colonial strategy to erase all indigenous elements in the area was far from complete, but certainly added a new dimension and incited the transformation of their socio-historical significance. This, in turn, played a role in structuring the post-colonial development of current local cultures in the region. Indigenous elements are present in the extensive use of traditional agricultural practices (slash and burn, conucos), as well as in the intensive use of indigenous plant species for economic and curative purposes, aspects that constitute an important part of everyday life in the region today (Pagán Jiménez pers. comm. 2016).

Another element of continuity is the current regional economy of the mangroves along the coast, which were also previously used by indigenous peoples. These are now exploited using traditional techniques of mollusc collection and indigenous fishing pens. Then there is also the construction of traditional houses, where materials and techniques recalling indigenous cultural traditions are used (Figure 10a & b). Similarly, the choice of construction location for houses also considers elements such as elevation, visibility, access to water sources, flood protection and ease of connection to different places or environments. In some cases, this has led to the reuse of places formerly inhabited by indigenous peoples, where aspects of former settlement patterns are still present in the conceptualisation and management of space by the present inhabitants.

Figure 10. Recording of indigenous legacies, Dominican Republic: a) house built with traditional techniques and materials in Amina; b) fishing pens in Caño Miguel. Haiti: c) baking cassava bread, Limonade; d) canoes and fishing traps, Lagon aux Bœufs. (Photographs by Jorge Ulloa Hung and Joseph Sony Jean.)

Also important is the use of ‘indigenous’ artefacts and images in ritual practices and the persistence of popular narratives. These are associated with the symbolism attributed to certain landscapes of the region, including watercourses, ponds, caves, rocky coasts and other geographical features. These constitute the scene of legends: magical, religious or healing practices, in which the ‘indigenous’ forms part of a complex cultural biography of the landscape where ideas and beliefs of different historical origins and trajectories overlap and mix (Pesoutova & Hofman Reference Pesoutova, Hofman, Ulloa Hung and Valcárcel2016). In Haiti, indigenous traditions have often been neglected in the past in order to support the idea that African heritage is the foundation of Haitian culture and identity. Indigenous traditions and cultural elements related to material and immaterial cultures, oral traditions, linguistics and narratives have clearly survived, however, and are now vital in Haitian society (Sony Jean pers. comm. 2016).

Ethnographic surveys carried out in the Meillac village, which is dominated by the Lagon aux Bœufs, Lamatry and Massacre Rivers, revealed that the current community members use both tools (canoes, baskets) and techniques of fishing descended from past Amerindian traditions (Figure 10c & d). The making of cassava bread and the uses of calabash in daily activities, as well as during Vodou practices, are also strongly linked to Amerindian traditions. Religious practitioners use caves and petroglyphs for spiritual and ritual purposes, as was probably the case for pre-Contact peoples. The indigenous traditions today are the result of the strong Amerindian-African interactions that took place during the colonial period, in which the transmission and sharing of ideas and knowledge were shaped (Beauvoir-Dominique Reference Beauvoir-Dominique and Cosentino1995). In fact, primary sources and archival data, hitherto unexploited, highlight evidence for the co-habitation of Amerindians and Africans during the colonial period (Sony Jean pers. comm. 2016).

Final remarks

New archaeological investigations and the recording of contemporary cultural traditions in northern Hispaniola have provided novel and important insights into the indigenous histories and legacies of the region in which the first Amerindian-European confrontations of the Americas took place. Our studies reveal the existence of a complex and diverse socio-cultural landscape on the eve of colonial encounters. The earliest evidence for settlement in the area dates to AD 800, but increases in site density indicate population growth after AD 1000–1200, and especially between AD 1200 and the time of contact. A settlement system with villages of various sizes, in different geomorphological and topographical locations and with various complementary functions, dominated the area. Some of the villages were probably important nodes in larger, regional networks, and show their connectedness through the co-occurrence of shared cultural traditions. The choice for settlement location reflects regional and local management of space, which in many cases is clearly related to control over resources. The site configurations with mounds and levelled areas appear to be very specific to the northern provinces. The low concentrations of European artefacts in early Contact sites have also been noted for other indigenous sites in the region such as En Bas Saline, in Haiti (Deagan Reference Deagan2004), and Playa Grande (López Belando Reference López Belando2013) and El Cabo, in the Dominican Republic (Samson Reference Samson2010).

The explicit settlement pattern and management of regional and local space, in addition to the mixture of material culture styles in the northern Hispaniolan sites, allude to the social and cultural diversity of the region experienced by the Europeans at the time of contact. It reflects a connected environment, an aspect taken advantage of by the Europeans during their first explorations of the interior of the island, which laid the foundations for a route that would become instrumental in carrying out colonial domination, which itself is characterised by the establishment of a system of fortifications. In this sense, the spheres or lines of social interaction between indigenous communities, from pre-colonial moments onward, cemented a regional history marked by coexistence, interaction and transculturation. Finally, the persistence of indigenous cultural traditions and knowledge in the present-day Dominican Republic and Haiti strongly counters the idea of substitution, displacement or disappearance as suggested by the traditional historical criteria.

Acknowledgements

The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Research Council under the European Union's Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007–2013)/ERC-NEXUS1492 grant agreement 319209. We acknowledge the Ministry of Cultures of the Dominican Republic and Haiti, the Museo del Hombre Dominicano and the Bureau d'Ethnologie d'Haiti for granting permission for our research. We are particularly grateful to the landowners, local communities, volunteers and field-school students for participating in the investigations and sharing their invaluable knowledge with us. Maps, drawings and photographs were made by co-authors Menno Hoogland, Eduardo Herrera Malatesta, Joseph Sony Jean, Till Sonnemann, Jorge Ulloa Hung with the help of Sven Ransijn for Figure 4. Editorial help was provided by Angus Martin and Alvaro Castilla-Beltrán. Finally, we thank William F. Keegan and an anonymous reviewer for their valuable comments.