Introduction

Rock art has an important place in the culture of many geographical areas by establishing and displaying communities' shared identities and/or signifying use of the land (e.g. Brady & Taçon Reference Brady and Taçon2016); however, its presence or influence in contemporary art is still a little-recognised phenomenon (Rozwadowski & Hampson Reference Rozwadowski and Hampson2021). Although work that is influenced by rock art in contemporary art has been noted in different parts of the word, such as in Australia or Africa (e.g. permanent exhibition ‘Threads of Knowing’ by Tamar Mason in the Origins Centre, Johannesburg), some regions are less known in this regard. ‘Rock art as a source of contemporary cultural identity’ is a research project that considers two regions that have so far received little attention in this context: Central Asia (covering southern Siberia and Kazakhstan) and Canada. The main focus of this research is the work of contemporary Indigenous artists and assessing to what extent references to rock art, and sometimes more widely to prehistoric art, constitute a source of cultural identity in their work. What kind of imagery do artists use, what factors determine the choice of particular motifs, to what extent are those choices inspired by archaeological interpretations or co-operation with archaeologists and how is rock art inscribed in the narratives construed by the artists? These questions lie at the heart of the research, which aims to demonstrate how important rock art is today and to show that archaeology is dealing with a socially sensitive heritage.

The two study areas have similar historical contexts associated with colonial tensions, which are still present in both Canada and post-Soviet Central Asia. Although southern Siberia, where much of the research was conducted (until Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022), is part of the Russian Federation, the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 triggered a series of identity-based actions revolving around rediscovering Indigenous traditions, myths and rituals, ancestral beliefs, as well as a new interest in the archaeological heritage. The research indicates that some similarities between Siberian and Algonquian worldviews may influence similarities in the aesthetics of the Indigenous art of both regions.

Siberia and Central Asia

In southern Siberia at the end of the twentieth century, the Siberian Neoarchaic (Russian сибирская неоархаика) artistic movement emerged, which was influenced by rediscovery and rethinking of Siberian archaic art and Indigenous culture. The movement was based in Tomsk, Krasnoyarsk, Novosibirsk, Barnaul, Gorno-Altaisk, and Novokuznetsk with its Siberian Art Gallery, which helped popularise the Neoarchaic art. The gallery organised numerous exhibitions, for example, ‘Trace’, ‘Chronotop’ and ‘Siberian Neoarchaic’. In Siberia, research was conducted in Khakassia, Altai, Krasnoyarsk Krai and Kemerovo Oblast. The first research region was the Republic of Khakassia, the homeland of the Turkic-speaking Khakas, where two highly original artists emerged: Alexander Domozhakov (1955–1998) and Alexei Ulturgashev (1955–2020) (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Alexei Ulturgashev presenting his work inspired by prehistoric Siberian art motifs at Abakan in 2018 (photograph by Andrzej Rozwadowski).

This research involved interviewing artists, documenting their works and, in the case of deceased artists, documenting the work held in museum archives or private collections as well as consulting people who knew the artists.

The work of Domozhakov was the main focus of the research in Khakassia. Over the course of his short life, Domozhakov created a collection of paintings that incorporate prehistoric rock art, stone stelae and Khakassian myths and beliefs, including shamanism (Figure 2). Of particular note is his collection of paintings dedicated to the Okunevo stelae, which are also a frequent subject of works by other Khakas artists, such as Ulturgashev, Kyzlasov and Krasnov.

Figure 2. Left) Spirit of the Night by Alexander Domozhakov, oil on canvas, 1.6 × 1.1m, 1991 (collection of Olga Akhrimchik); right) the Bronze Age stela of the Okunevo culture (Khakas National Museum of Local Lore) (photographs by Andrzej Rozwadowski).

The Neoarchaic art movement is not as strong as it was just a decade ago, but the phenomenon of taking inspiration from Siberian rock art and other forms of prehistoric art is still important in the work of a new generation of artists (such as Arzhan Yuteev from Gorno-Altaisk). They see rock art as a symbolic link to their ancestors, and through their art they awaken the Indigenous cultural consciousness obliterated during Soviet times.

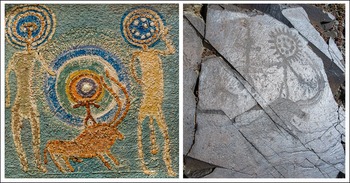

In Kazakhstan, studies for this project involved Uighur artist Akhmet Akhat and the now legendary Abdrashit Sydykhanov, who was one of the founders of the so-called ‘icon/sign painting’ (inspired by tamgas, ancient Turkic ownership marks, and petroglyphs), a symbolic trend in the Kazakh fine arts (Figure 3). Both artists produce work based on the famous petroglyphs from the Tanbaly/Tamgaly Valley, which became a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2004.

Figure 3. Left) Abdrashit Sydykhanov Planet Moon, mixed materials, 700 × 700mm, 1996 (collection of Zauresh Sydykhanova); right) the petroglyphs from the Tanbaly—the anthropomorph standing on the bull is about 400mm high (photographs by Zauresh Sydykhanova & Andrzej Rozwadowski).

Canada

In Canada, contemporary Indigenous art has a strong connection to rock art (Figure 4). One of the first twentieth-century artists inspired by rock paintings was Norval Morrisseau—also called Copper Thunderbird—the Ojibwa (a First Nations people of the region around Lake Superior) pioneer of modern Indigenous Canadian art. Morrisseau was the first to break the local taboo of not depicting Indigenous knowledge. His innovative style consisted of vivid images painted with black contour lines and colourful images of people, animals and plants and it laid the foundation for the Woodland Style school, which many other artists followed. Morrisseau's interest in rock art began with an encounter with Selwyn Dewdney, the ‘father’ of rock-art research in Canada. Domozhakov in Siberia and Sydykhanov in Kazakhstan had similar experiences, which significantly inspired them to explore ‘their’ archaeological heritage. Contemporary Canadian Indigenous artists also formed an artistic movement—the Professional Native Indian Artists Incorporation, founded in 1973.

Figure 4. Entrance to the Ojibwe Cultural Foundation (M'Chigeeng, Manitoulin Island, Ontario). Six human figures designed by Carl Beam (1999) were inspired by rock art and described by Beam as “figures from our cultural past” (Hill Reference Hill2010: 57) (photograph by Andrzej Rozwadowski).

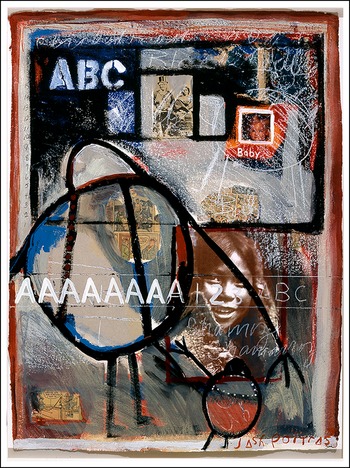

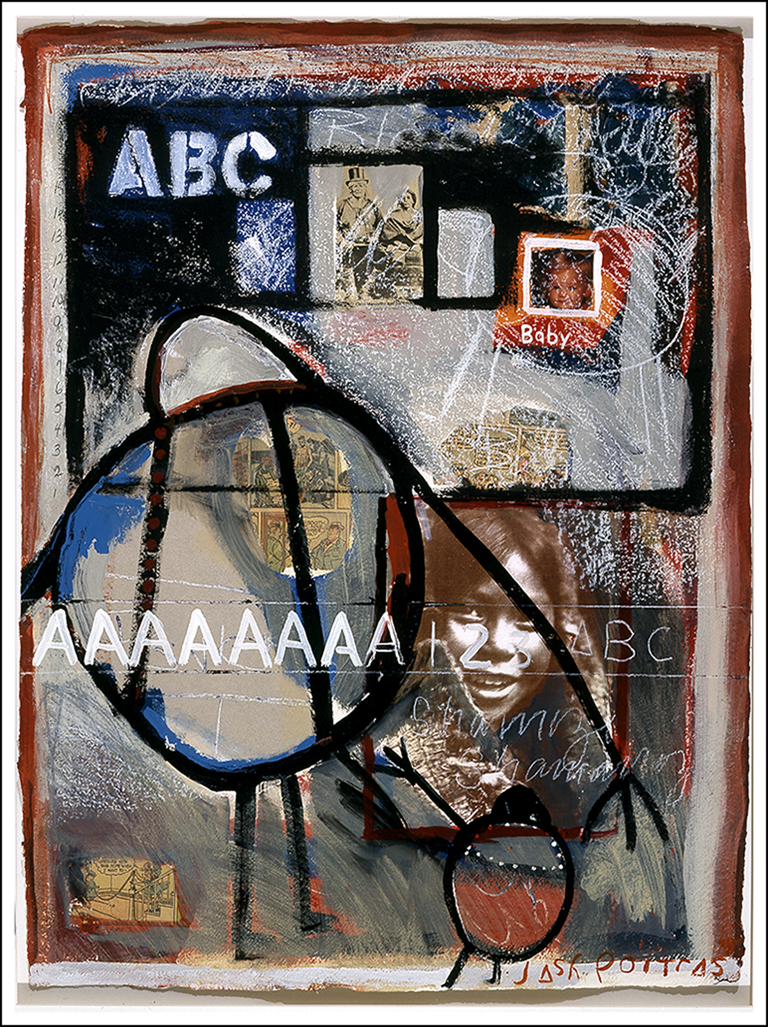

Inspiration from rock art images in Canada is more obvious in modern art, compared with other regions, partly because in some areas making rock art was a living tradition until the first confrontations with the colonisers took place in the sixteenth century. Various twentieth-century Indigenous artists referred to the rock paintings instinctively, because they were an intrinsic part of their lives—Ojibwa artists Carl Ray and Roy Thomas (based in Ontario) did so even more forcefully than Morrisseau. When their Indigenous heritage was being forgotten by younger generations under conditions of increasing colonisation, the artists became a medium for recalling this tradition. As a result, rock art became an important sign of indigeneity, as it did for subsequent generations of Indigenous artists, including Carl Beam, Blake Debassige (Ontario), Jane Ash Poitras and Joane Cardinal-Schubert (Alberta), to name a few (the 1980s generation).

Part of the research focused on Jane Ash Poitras and Joane Cardinal-Schubert, whose work often refers to rock art, particularly that found at Writing-on-Stone Provincial Park in southern Alberta (Figure 5). Just as the rock images at Writing-on-Stone continue to be objects of reverence for First Nations people, they are, in the works of Poitras and Cardinal-Schubert, used as decolonising symbols intended to heal some wounds in Indigenous history. In the works of artists of this generation, other techniques became equally important, such as ‘combine painting’—hybrid artworks that blend painting with collage and an assemblage of a wide range of objects taken from everyday life—expressing the fragmentary character of Indigenous history scattered by numerous traumas, including residential schools. This example of trauma saw thousands of Indigenous children taken from their parents during the 1960s and 1970s and placed in foster care in ‘residential schools’. In Canada, the last one closed in 1997. In addition, the technique of incorporating photographs of First Nations persons whose souls were believed to have been stolen by cameras is characteristic of Poitras's work (Figure 6). By combining the photographs with rock art motifs, the artist turns these ancient rock art images into a healing medium—that is, one that restores the Indigenous soul.

Figure 5. Writing-on-Stone Provincial Park, southern Alberta, and its petroglyphs (photographs by Andrzej Rozwadowski).

Figure 6. Jane Ash Poitras's Spanish Roots, date unknown; oil, acrylic, newspaper oil pastel, crayon and graphite on paper, 771 × 566mm (image courtesy of Art Gallery of Alberta Collection).

The use of rock art images as symbols of the primacy of Indigenous peoples within their native land continues in the work of many recent Indigenous artists in Canada. In Nova Scotia, the Mi'kmaq artist Alan Syliboy revitalises his heritage by including images of Kejimkujik petroglyphs. On the other side of Canada in British Columbia, there are spectacular contemporary rock paintings of Coppers—heraldic copper plaques used by North Pacific Coast nations as value currency and potlatch ritual exchange objects—made by Dzawada'enuxw visual artist Marianne Nicolson on the huge cliff in the Kingcome Inlet.

Conclusions

The project shows that contemporary artists apply rock art motifs deliberately in their work to emphasise their link with the land, often regardless of how differently archaeologists associate them with pre/historical cultural processes. Rock art images incorporated into artworks communicate the continuity of Indigenous knowledge and power capable of restoring Indigenous values. Some artists take inspiration from rock art to visually restore an Indigenous worldview, but do not depict these images in their works. The project thus reveals different dimensions of artists’ use of rock art, and how they are embodied in identity narratives.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank Jane Ash Poitras, Alan Syliboy, Louis Thomas and Ahnisnabae Art Gallery, Rebeca Toly and Writing-On-Stone Provincial Park, Jackie Bugera and Bearclaw Gallery, Glenbow Museum, Art Gallery of Alberta, McMichael Canadian Art Collection, Khakas National Museum in Abakan, Museum of Local Lore in Minusinsk, Historical Museum in Chernogorsk, the family of A. Domozhakov, and Olga G. Akhrimchik, Olga M. Galygina, Sergei Dykov, Vitalii N. Kyzlasov, Sergei G. Narylkov, Zauresh Sydykhanova and Arzhan Yuteev.

Funding statement

The research results from the Grant 2017/25/B/HS3/00889, National Science Center, Poland.