Introduction

Surveys carried out around Mount Chikiani (2417m) in the Caucasus of Georgia during 2016 have demonstrated the importance of the unique Bronze Age obsidian mining areas located along the northern slope of the volcano (Biagi et al. Reference Biagi, Nisbet and Gratuze2017a & b). Further surveys in 2017 discovered a large number of other important features scattered within a radius of approximately 9km eastward from the volcano, covering a total area of approximately 45km2. Although the research is far from complete, the recent discoveries help to define the exploitation of a high-altitude archaeological landscape that extends well beyond the territory suggested by previous fieldwork.

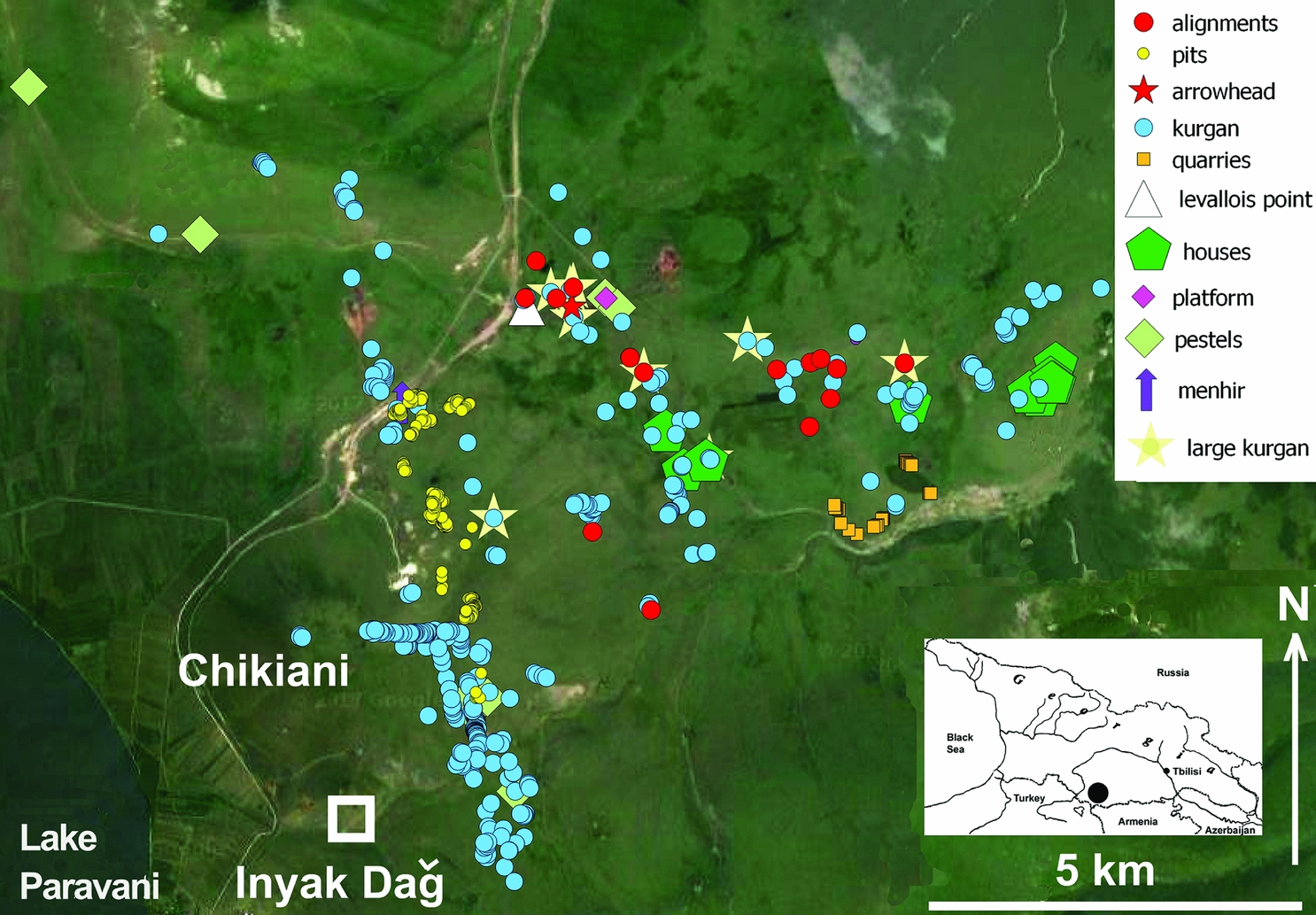

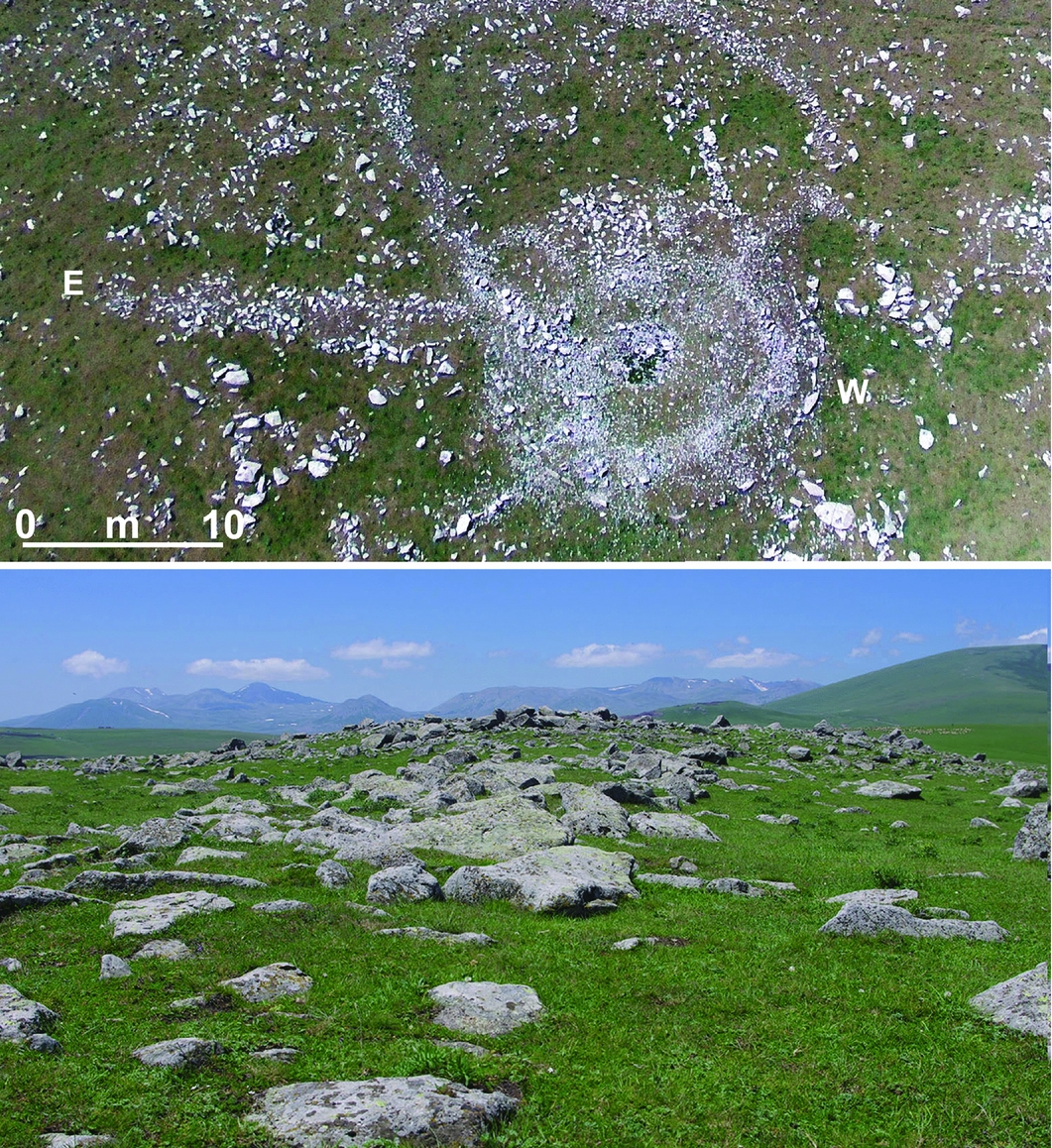

Figure 1 shows the variety and extent of known local archaeological features. These include settlements and burials, kurgans (stone burial mounds) standing both separately and in alignments, basalt quarries and a putative, partially excavated ‘fortress’ located on Inyak Dağ (2294m asl), a small cinder cone offering strategic views of the local terrain (Narimanishvili & Khimshiashvili Reference Narimanishvili, Khimshiashvili and Beridze2009). Also present is evidence for extensive local obsidian working in the form of manufacturing areas and tools (Figure 2) made using obsidian from eight documented lava flows (Nasedkin et al. Reference Nasedkin, Sergeev, Alibegashvili and Rixiladze1983).

Figure 1. Distribution map of the different types of archaeological features discovered around Mount Chikiani during the 2016 and 2017 surveys (map by R. Nisbet).

Figure 2. Circular stone platform discovered 7km north-east of Mount Chikiani, on which obsidian artefacts were knapped. Inset: an obsidian arrowhead from the same platform (photographs by P. Biagi).

The stone structures

Kurgans

Apart from the intense obsidian mining already recorded along the northern slopes of the volcano (Badalyan et al. Reference Badalyan, Chataigner, Kohl and Sagona2004; Biagi & Gratuze Reference Biagi and Gratuze2016; Biagi et al. Reference Biagi, Nisbet and Gratuze2017b), an impressive number of monumental structures were discovered and GPS-recorded during the surveys. The most frequent features consist of simple, circular or elliptic stone heaps approximately 2–5m in diameter and made of local basalt or andesite blocks, although large obsidian pebbles are also occasionally used. ‘Kurgan’ may be somewhat inappropriate to define these small stone tombs, considering the complex funerary mounds excavated in the region (Gobejishvili Reference Gobejishvili1980). The word is, however, used here due to their similar burial function.

Kurgans are distributed almost throughout the surveyed area, and represent the most frequently identified (384) stone features. They sometimes form alignments several hundred metres long. More rarely, ‘monumental’ kurgans occur, complete with one or two causeways marked by stone alignments (Figure 3). These are similar in form to those already known from the Tsalka reservoir (Zischow Reference Zischow2004; Motzenbäcker & Narimanishvili Reference Motzenbäcker and Narimanishvili2011: 73–84) and to numerous other kurgans in the Trialeti region (Narimanishvili Reference Narimanishvili and Gamkrelidze2010).

Figure 3. Monumental kurgan K-105 with entrance corridor oriented in an east–west direction, facing north (photographs by M. Ferrandi and P. Biagi).

Wall alignments

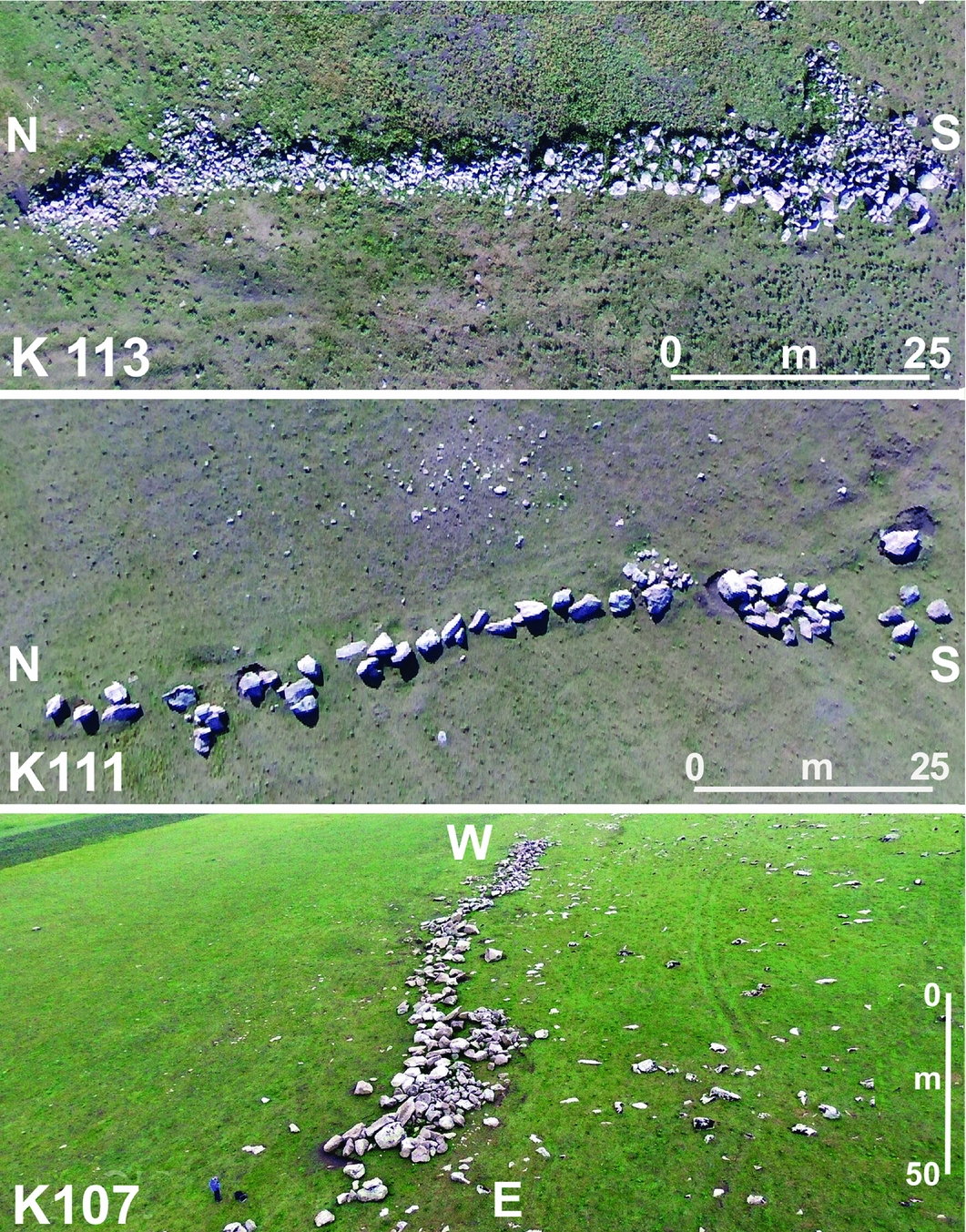

In contrast with kurgans, long, rectilinear stone structures have no regional comparisons. Most of these structures were discovered in the eastern sector of the surveyed area. They are 70–110m long and either north–south or east–west oriented (Figure 4). Very large blocks—some well over 1m in diameter—were taken from their original location and arranged in one or two parallel rows. No evidence of carving was noted, although a few small obsidian flakes were collected from the bottom of the boulders and from small trial-trenches opened along the sides of the structures.

Figure 4. Stone alignments K-113, K-111 and K-107 (photographs by M. Ferrandi).

The structures are probably prehistoric, given the general chronology of the Chikiani archaeological record. The construction methods employed in their creation are not yet understood. How were these boulders transported across uplands and an open, treeless subalpine meadow? Recent coring may offer an insight. Pollen from local cores suggests a spread of coniferous forests well above 2000m in the Middle and Late Holocene periods (Connor Reference Connor2006; Kvavadze & Narimanishvili Reference Kvavadze, Narimanishvili and Gamkrelidze2010; Messager et al. Reference Messager, Belmecheri, Von Grafenstein, Nomade, Ollivier, Voinchet, Puaud, Courtin-Nomade, Guillou, Mgeladze, Dumoulin, Mazuy and Lordkipanidze2013). These forests may have provided wood for the displacement and transport of boulders.

Other linear features observed near the volcano—of different function to the stone alignments—should be mentioned. Two of these are long linear banks (with ditches), which were probably water reservoirs. The third is a 65m-long structure, located close to a monumental kurgan (K-128). It is bordered by a causeway-like feature, upon the surface of which were frequently but sparsely distributed obsidian flakes.

A number of clearly more recent enclosures have disturbed older structures and kurgans (Figure 5: top). Abandoned corrals comprising boulder-built square or rectangular rooms are particularly difficult to distinguish from similar prehistoric stone structures.

Figure 5. Top: vertical stone structures, slabs and oval corrals; bottom: (top) and villa VIL-6 comprising two parallel rows of apsidal stone structures, facing south-west (photographs by P. Biagi and M. Ferrandi).

Settlements

The most enigmatic features discovered during the survey are concentrated on a terrace facing the steep Chochiani Valley, at the eastern border of the Javakheti plateau. These features control access to the plateau from the Tsalka. Abundant evidence of basalt quarrying has been recorded along the northern edge of this valley (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Basalt quarries along the edge of the terrace facing south towards the Chochiani River Valley (photographs by M. Ferrandi and P. Biagi).

Menhir

An aniconic standing stone (with no evidence of surface carving), approximately 3.5m high and locally known as Tikma-Dash, is located along the north-western lower slope of Mount Chikiani, very close to a group of obsidian mines. In 1940, B. Kuftin excavated some kurgans in this area and dated them to the third millennium BC (Narimanishvili et al. Reference Narimanishvili, Shanshashvili, Narimanihvili, Işiklı and Can2015: 215). Although we could not observe the suggested ‘snake’ carving on its sides (Narimanishvili et al. Reference Narimanishvili, Shanshashvili, Narimanihvili, Işiklı and Can2015), we noted the heavily degraded state of the menhir's surface. This degradation, combined with continuous heavy traffic nearby, will shortly threaten the monument.

Discussion

Bronze Age obsidian mining along the Mount Chikiani slopes involved reshaping the entire territory from the suggested intense use of the local forests through the construction of many kurgans, long megalithic alignments, living spaces and basalt quarries. The chronology of all these upland events remains unclear, and extensive radiocarbon dating is necessary to construct a reliable sequence. The 2016 and 2017 surveys, however, showed the complexity of a region that undoubtedly played a very important role during the metal ages of the Lesser Caucasus of Georgia and its neighbouring countries. This complexity can be attributed mainly to the rich obsidian sources that were mostly exploited during these periods, and whose importance has so far been underestimated.

Acknowledgements

Thanks go to V. Licheli (I. Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University, Georgia) for his assistance and support for the 2017 survey. The fieldwork was financially supported by Ca’ Foscari University of Venice Archaeological Research Funds, and by EURAL Gnutti. We are also wish to thank M. Ferrandi (Ca’ Foscari University of Venice) and two I. Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University students who took part in the survey.