Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 October 2020

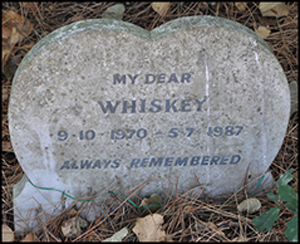

Pet cemeteries provide a unique opportunity to investigate the development of human-animal relationships, yet few archaeological studies of these cemeteries have been undertaken. This article presents an archaeological survey of gravestones at British pet cemeteries from the Victorian period to the present. These memorials provide evidence for the perceived roles of animals, suggesting the development of an often conflicted relationship between humans and companion animals in British society—from beloved pets to valued family members—and the increasing belief in animal afterlives. The results are discussed in the context of society's current attitude towards animals and the struggle to define our relationships with pets through the mourning of their loss.