Since 2012, the Palmyra Portrait Project (hereafter PPP) has collected and studied a vast corpus of funerary sculpture from Palmyra in Syria. Comprising over 3700 portraits, the corpus has contributed significantly to our understanding of local development and individual representation in antiquity (Raja Reference Raja2017a). Dating via associated inscriptions and the in situ presence of portraits provides a tight chronological framework—unique for material from the classical world. Harald Ingholt (Reference Ingholt1928) first developed a typology and chronology for the portraits based on a paper archive collected by Ingholt himself. Digitisation of Ingholt’s archive means that his chronology can now be checked digitally against the PPP’s and other scholars’—chronologies.

The Palmyrene portrait tradition was introduced along with monumentalised grave types in the first century AD (Raja Reference Raja2017b). These portraits, however, are distinctive and differ from standard Roman funerary busts, as they often depict individuals down to the mid-torso. The earliest grave monuments in Palmyra were the prominent grave towers (Henning Reference Henning2013; Figure 1), which were followed in the second century AD by underground tombs, or hypogea (Gawlikowski Reference Gawlikowski1970). Exclusive grave types, of Roman date too, such as temple or house tombs, are also found around the city (Schmidt-Colinet Reference Schmidt-Colinet1992).

Figure 1 Tower tombs in Palmyra (photograph by Rubina Raja).

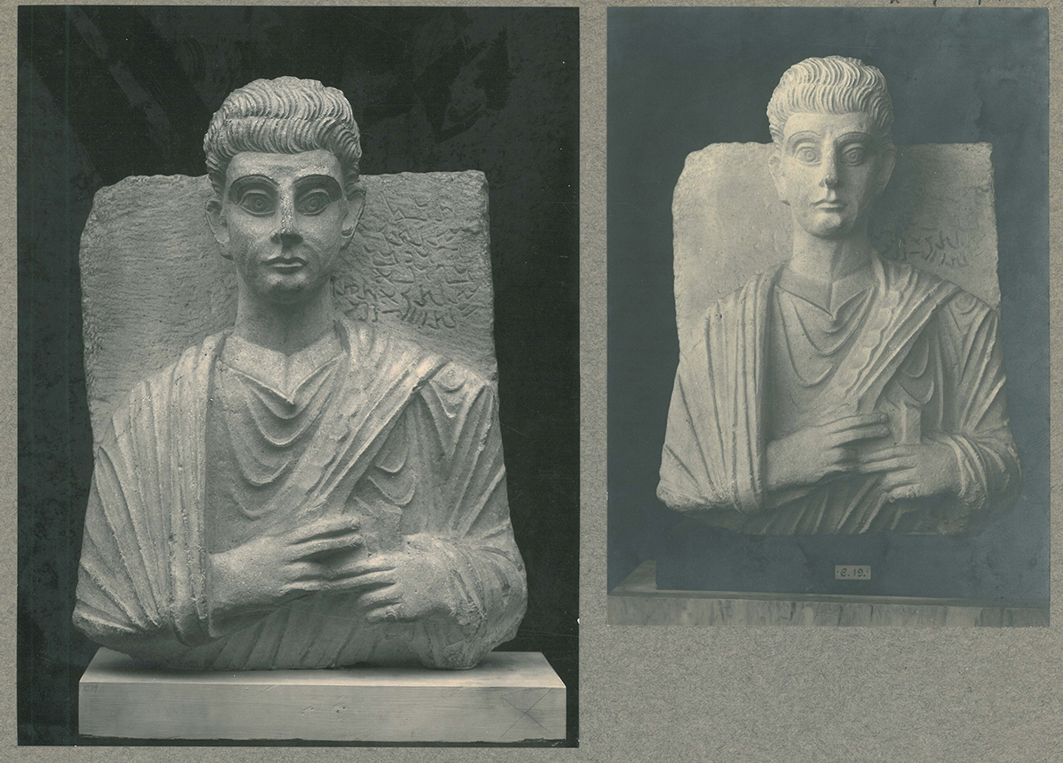

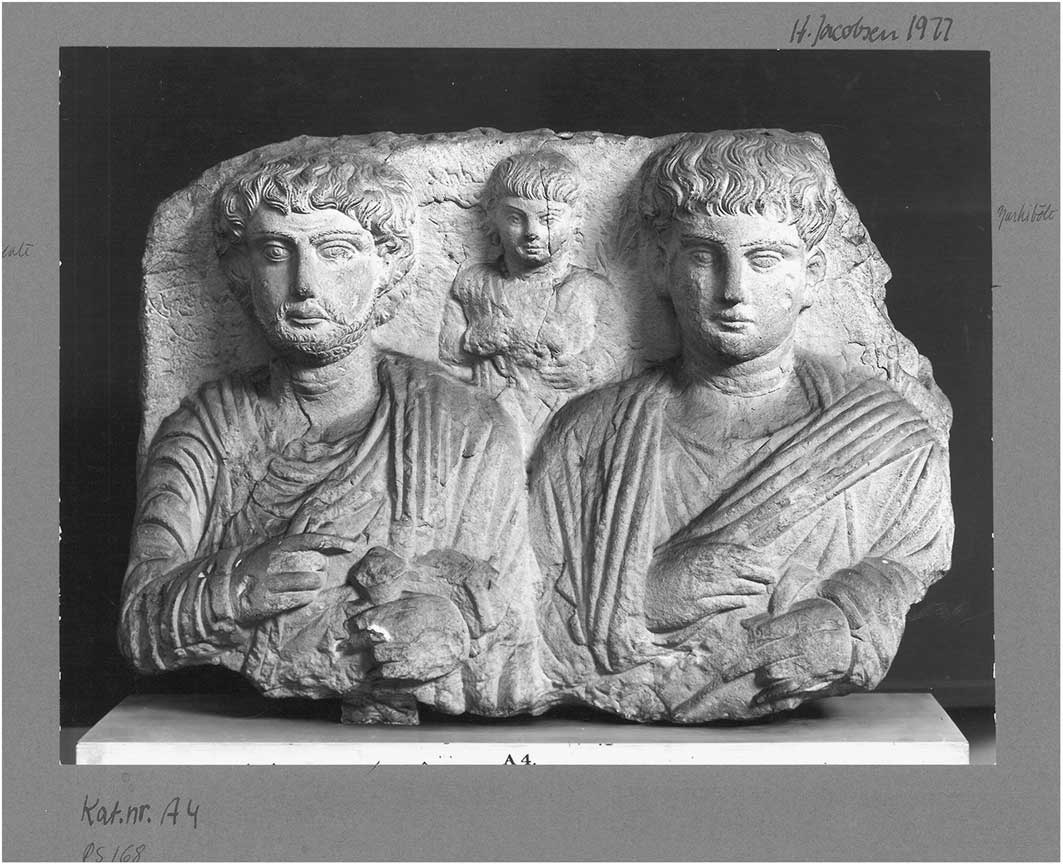

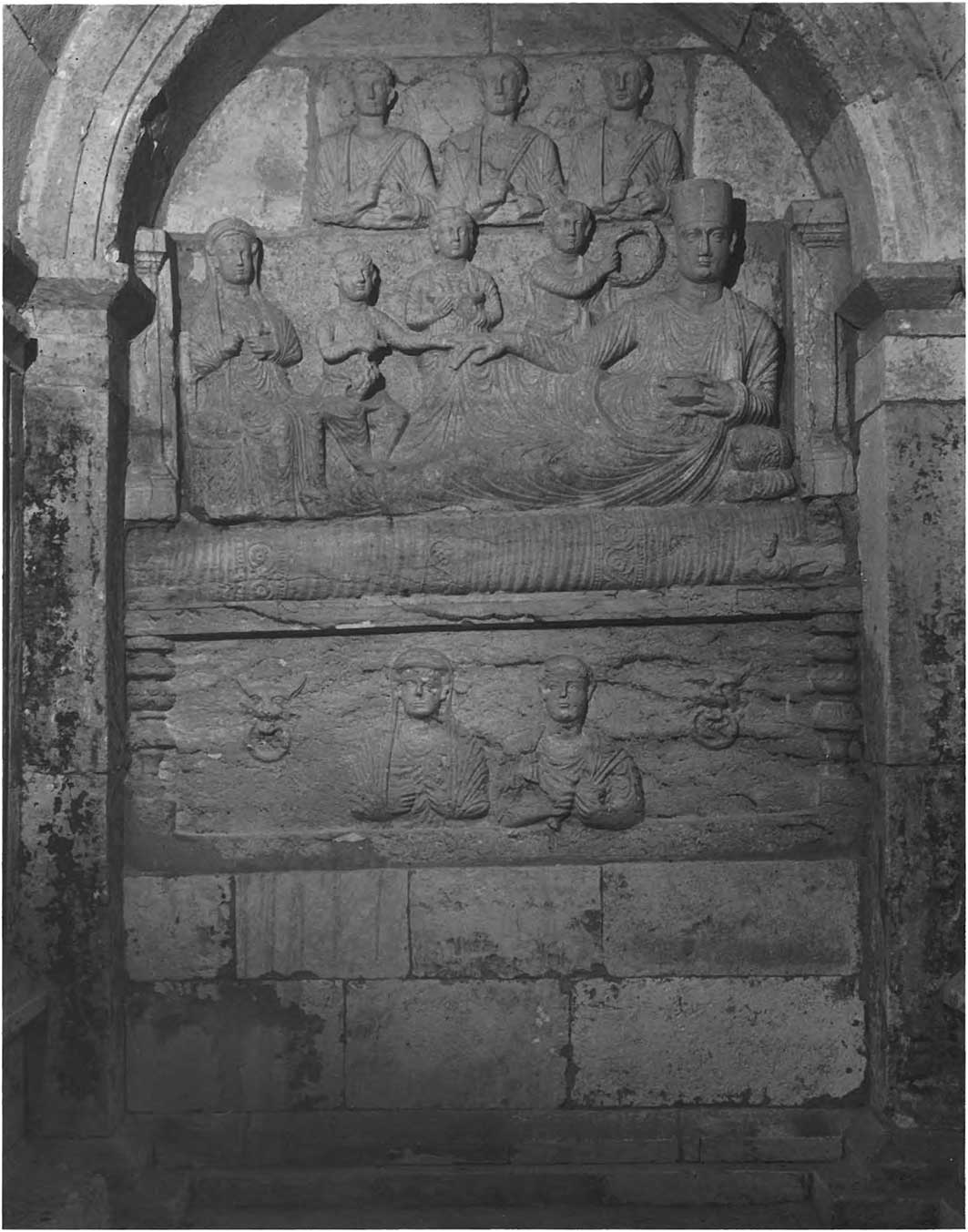

The types of portrait sculpture range from the common single loculus reliefs to elaborate banqueting scenes on sarcophagi lids. The former, more than 1000 of which are in the corpus, were rectangular slabs on which the busts were carved (Figure 2). Rarely, the loculus reliefs depict several individuals (Figure 3). Other types of representations are the full-figure, under life-size, loculus stelae (Figure 4), and banqueting reliefs (Figure 5) (Krag & Raja Reference Krag and Raja2017). Unique to Palmyra, reliefs of sarcophagi, along with sarcophagi themselves, were introduced in the second century AD (Figure 6).

Figure 2 Single loculus relief depicting a male bust holding a schedula, with a background inscription (Ingholt Archive IN 1049, courtesy of the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek).

Figure 3 Triple loculus relief depicting two male busts and a girl, with two background inscriptions (Ingholt Archive IN 1027, courtesy of the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek).

Figure 4 Loculus stele depicting two standing boys, with two background inscriptions (Ingholt Archive IN 2776, courtesy of the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek).

Figure 5 Banqueting relief depicting priest and wife, dated by two background inscriptions (IN 1159 & IN 1160, courtesy of the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek; photograph by the Palmyra Portrait Project).

Figure 6 Sarcophagus relief depicting banqueting scene on the lid and two busts on the box of the sarcophagus (after Tanabe Reference Tanabe1986: 31, pl. 229).

The PPP database was developed specifically to host sculpture—portraiture in particular. The database search functions allow for statistical analysis across all searchable elements, as well as the identification of specific elements. This in turns provides a new way to interrogate the large dataset efficiently. The dating of portraits, for example, can be combined with numbers within gender groups. One such case study using the database, for example, combined portrait dating with gender representations, and found that Palmyrene priests comprise approximately 25 per cent of all male representations from the funerary sphere, thereby offering insight into the structure of local Palmyrene religious life (Raja Reference Raja2017c & Reference Rajad).

Such results add new knowledge concerning priesthoods and local religious life. The database also allows inscriptions and their associated funerary portraits to be studied as integrated objects. This, for example, has demonstrated the importance of the Palmyrene family and ancestry (e.g. Long & Sørensen Reference Long and Sørensen2017). Furthermore, the ability to search the database of Syrian graves with in situ portraits enables important insights to be made into the diachronic use and expansion of the graves. Future work within the project will include computer modelling of Palmyrene population numbers. The corpus of Palmyrene funerary sculpture bestows classical scholars with a unique resource from one of the most famous locations in the Roman East. When published, the corpus will provide direct online access to this data. The PPP has demonstrated the benefits of digitising materials from the classical world, particularly as the database is designed specifically with such material in mind.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks the Carlsberg Foundation for funding the project. Special thanks go to all project members and collaborators, along with the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen, and Jean-Baptiste Yon, CNRS, Lyon.