Introduction

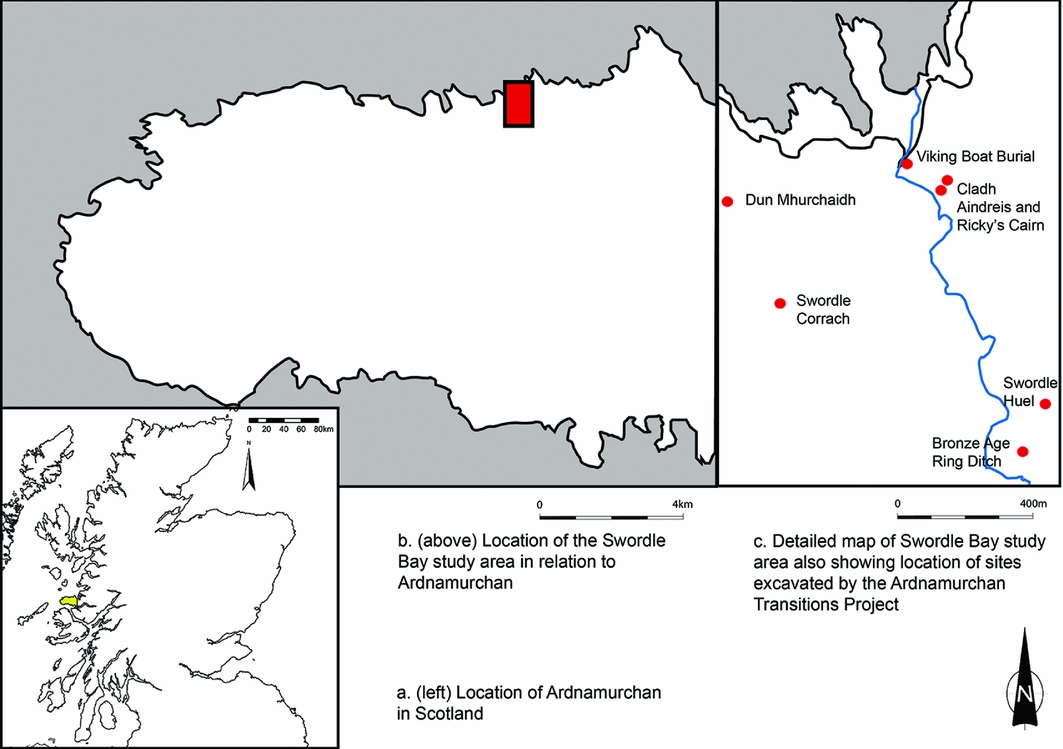

Viking boat burials are iconic archaeological discoveries. Wonderfully preserved examples discovered at Oseberg and Gokstad in Norway have sparked the imagination, and both archaeologists and the general public remain fascinated by these acts of conspicuous consumption. In the UK, examples are well known from the Scottish islands, including Orkney (e.g. Scar: Owen & Dalland Reference Owen and Dalland1999), Shetland (e.g. Aith, Fetlar: Batey in press) and Colonsay (Kiloran Bay: Anderson Reference Anderson1907), as well as from the Isle of Man (e.g. Balladoole: Bersu & Wilson Reference Bersu and Wilson1966). Until recently, however, no intact boat burials had been excavated by archaeologists on the UK mainland. That changed in 2011 when the Ardnamurchan Transitions Project, which examines long-term change on the Ardnamurchan peninsula, western Scotland, discovered and excavated a boat burial in Swordle Bay on the peninsula's north coast (Figure 1). Although not as spectacular in size as some of the Scandinavian examples, it nevertheless represents a rich Viking grave, adding significantly to the corpus of examples from Britain. Dating most probably to the early tenth century AD, the grave assemblage included a rich collection of artefacts.

Figure 1. Location map of the Viking boat burial and other sites excavated by the Ardnamurchan Transitions Project.

An interim publication of our findings was made immediately after the excavation (Harris et al. Reference Harris, Cobb, Gray and Richardson2012), and here we present the excavation in detail for the first time, alongside the grave goods and isotopic evidence that hint at a possible Scandinavian origin. This burial provides another important insight into the contacts between Scotland, Ireland and the Viking homeland in the early tenth century. Furthermore, the assemblage also offers the opportunity to reflect on wider questions around the performance of identity.

The archaeology

The site was initially recorded as a low-lying mound close to the foreshore, respected by later rig-and-furrow agriculture. Excavation established that the mound itself was natural, with a central, cut feature, within which a substantial number of medium to large stones had been placed in a boat-shaped setting, including two layers of kerbing around the edge of the cut. The arrangement measured 5.2 × 1.7m at its widest point and was orientated west-south-west to east-north-east (Figure 2). A spearhead and shield boss were recovered from amongst the stones, presumably included as part of the process of closing the grave.

Figure 2. Pre-excavation photograph after initial cleaning.

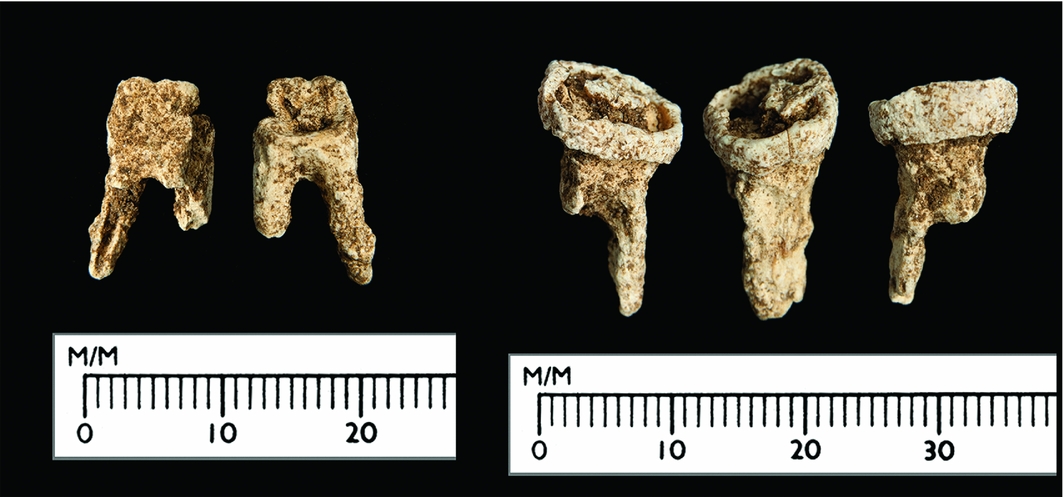

At the base of the feature, two finds-rich layers provided extensive evidence for the rivets of a complete, clinker-built boat containing numerous grave goods. These included a sword, an axe, a large ladle containing a hammer and tongs, a drinking horn mount, a ringed pin, a sickle, a whetstone and flint strike-a-lights. Unlike the spear and shield, these items appear to have been placed next to the interred individual. The upper of the two layers also contained two teeth: both molars from the same individual. These were the only identified human remains, the rest of the body having probably decayed in the acidic soil; the location of the teeth suggests the head was towards the west end of the boat.

Turning this archaeological sequence around, we can reconstruct the burial. A boat-shaped depression was first cut into a natural mound of beach shingle (Figure 3). After a brief period of silting (perhaps no more than a few hours), the boat was inserted. Into this was placed the body and around it the majority of the finds. Stones were then placed in and around the boat, beginning with two layers of kerbing; the spear and shield were included at this stage.

Figure 3. Post-excavation photograph of the cut.

The finds

The vessel itself survived in the form of 213 rivets recovered in situ and recorded three-dimensionally (Figure 4); a handful more had been disturbed. This was clearly an intact craft measuring approximately 5.1m in length and would have been a small rowing boat, probably accompanying a larger ship, rather than being a serious sea-going craft. The survival of mineralised wood connected to the decaying rivets should allow further information about the boat to emerge in due course.

Figure 4. Plot of the in situ rivets (by Irene Garcia Rovira).

Immediately behind the probable location of the head of the buried individual, towards the western end of the boat, was a large iron ladle. The pan was around 270mm in diameter with a handle over 0.5m long. Various items had been placed within the bowl, including a hammer and a pair of tongs, as well as organic remains, potentially foodstuffs (Greaves Reference Greaves, Harris, Cobb, Gray and Richardson2011). Some mineralised wood fragments also adhered to the base of the ladle, probably representing original boat timbers. The ladle has Scandinavian parallels as well as a more local one at Kiloran Bay on Colonsay, but is not common in a British context (Batey in press).

A number of other artefacts were placed on and around the body itself (Figure 5), including a single copper alloy ringed pin, which may have fastened the burial cloak or shroud (Figure 6). The ring has three bosses, a style that appears to come from Ireland (Graham-Campbell & Batey Reference Graham-Campbell and Batey1998: 116), implying southward connections. Between the pin and the ladle was a copper alloy drinking horn rim. Relatively undecorated apart from two simple, incised lines, it could either be insular in origin or may equally have a Scandinavian connection (cf. Paterson et al. Reference Paterson, Parsons, Newman, Johnson and Howard Davis2014: 149–51). The position of the horn suggests it may have been laid to the south (or the right side) of the head.

Figure 5. Plot of the major finds recovered from the grave. Note: this is a two-dimensional plan. The spear and shield were higher in the fill than the other finds (by Irene Garcia Rovira).

Figure 6. Some of the other finds recovered from the grave (clockwise from the top left): broad-bladed axe, shield boss, ringed pin and the hammer and tongs (photographs: Pieta Greaves/AOC Archaeology).

Other items were found more centrally in the grave, either on the body itself, or interred below it. These included the whetstone, probably of southern Norwegian schist (Askvik with Batey Reference Askvik, Batey and Lucas2009: 294–95), and the flint strike-a-lights and iron sickle. The latter is paralleled by several examples in Scotland, e.g. from Westness and Pierowall in Orkney (Graham-Campbell & Batey Reference Graham-Campbell and Batey1998: 135–37, figs 7.10 & 7.11) and from Kneep in Lewis (Welander et al. Reference Welander, Batey and Cowie1987: 151–52, 158–59). There are also many known in Norway, as discussed by Petersen (Reference Petersen1951: 515–16), particularly in the west of the country.

Located between the edge of the boat and the north-west (left) side of where the body may have lain was the sword (Figure 7). This appears to have been deposited missing its tip, a feature also noted at Balnakeil in Sutherland (Batey & Paterson Reference Batey, Paterson, Webster and Reynolds2013: 637). It had been bent in a shallow S-shape, potentially indicating deliberate damage before deposition—something we also see with the spear. Around the blade, however, are the remnants of leather from a sheath, the presence of which suggests that the change in sword shape took place after deposition. Further investigation of this material is required to resolve this question. Adhered to the sword were mineralised textile remains, either from textile wrapping around the sword and sheath itself, or from the clothes or shroud worn by the deceased, as perhaps paralleled at Scar (Nissan Reference Nissan, Owen and Dalland1999: 109–10). Both the guard and the pommel of the sword are finely decorated with silver and copper wire, and typologically the sword appears to be a Petersen Type K, with suggestions of Type P and Type O (Petersen Reference Petersen1919; Batey in press; Gareth Williams pers comm.). This provides the major evidence that this burial has a terminus post quem of the late ninth or early tenth century AD.

Figure 7. The sword (top); the sword in situ (below); the mineralised textile remains (right); detail of the decoration after conservation (left) (lower photographs: Pieta Greaves/AOC Archaeology).

To the east, perhaps near the feet, was a broad-bladed axe (Figure 6), with part of its wooden handle preserved in mineralised form. Similar examples from a slightly later date are known from Dublin (Halpin Reference Halpin2008: 164). One additional set of artefacts associated with the body was a closely packed group of rivets in the east end of the boat. These appear to have been deposited together, possibly in a bag—perhaps a repair kit?

The final artefacts found in the boat, the spear and shield boss (Figure 6), were higher in the burial, deposited as part of the closure of the monument. This performative element of burial is supported by the fact that the spearhead (Petersen Type E; Petersen Reference Petersen1919: 26–28) was deliberately broken before being deposited. The shield appears to have been deposited with the spear and has sustained damage at the crown, and the flange is distorted (with traces of the shield board remaining), yet it remains unclear at what stage this occurred. Both items were positioned centrally, and although the stones kept them separate from the corpse, they probably corresponded with the mid to lower part of the body.

The isotopes

The two surviving teeth were micro-CT scanned to obtain a digital record prior to sampling for isotope analysis, as macroscopic preservation appeared to be poor (Figure 8). They were identified (by the internal patterns of their root canals) to be lower left first and second molars. Both enamel and dentine were present in the lower second molar, and the CT scans demonstrated that both retained the expected density and structure of modern tissues, and had potential to produce viable data.

Figure 8. The Viking's teeth.

To investigate the individual's origins, strontium, oxygen and lead isotopes, and strontium and lead concentrations were obtained from the enamel in the second molar crown, which mineralises between the ages of approximately 2 and 6 (AlQahtani et al. Reference AlQahtani, Hector and Liversidge2010). In addition, carbon and nitrogen isotope profiles were produced from incremental dentine samples from the same tooth following the method of Beaumont et al. (Reference Beaumont, Gledhill, Lee-Thorp and Montgomery2013). These represent diet between the approximate ages of 2 and 15.

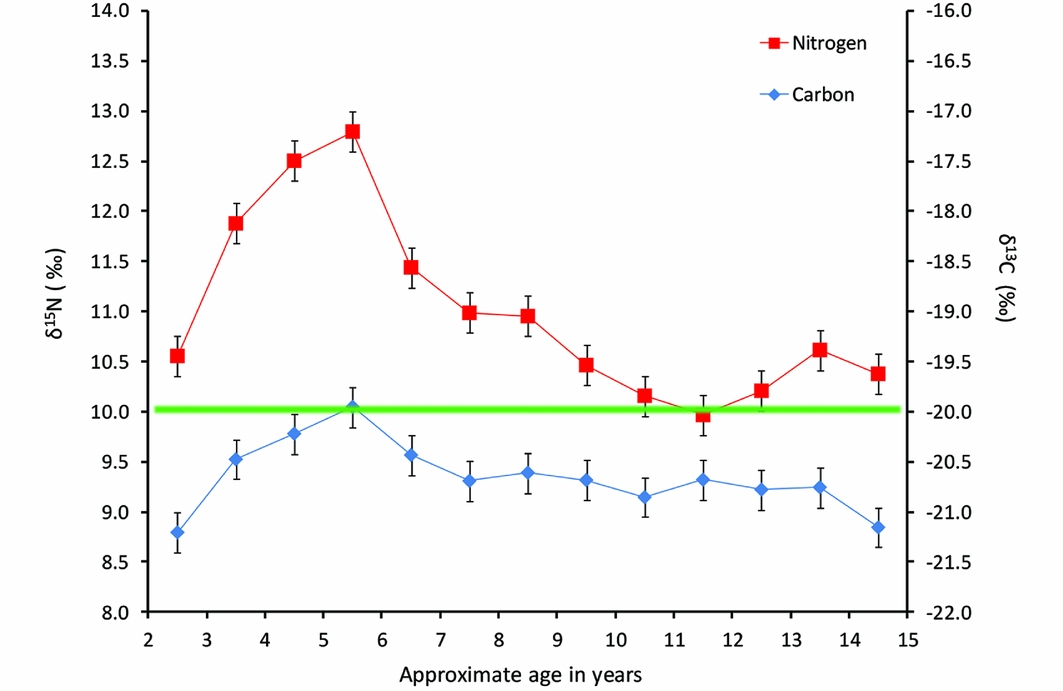

Results indicate that the individual consumed a largely terrestrial diet up to the age of 15, with a period of increased marine protein consumption between the ages of 3 and 5 (Figure 9). Isotopic evidence for marine protein consumption by humans is rare in Britain in the first millennium AD, even at coastal sites (Barrett & Richards Reference Barrett and Richards2004; Müldner & Richards Reference Müldner and Richards2007; Müldner et al. Reference Müldner, Montgomery, Cook, Ellam, Gledhill and Lowe2009; Buckberry et al. Reference Buckberry, Montgomery, Towers, Müldner, Holst, Evans, Gledhill, Neale and Lee-Thorp2014; Curtis-Summers et al. Reference Curtis-Summers, Montgomery and Carver2014), but both non-marine and marine protein consumers are found in Viking Age Norway; children appear to eat less marine protein than adults (Kosiba et al. Reference Kosiba, Tykot and Carlsson2007; Naumann et al. Reference Naumann, Price and Richards2014). Evidence for marine consumption in childhood may indicate that the individual was living on or close to the coast.

Figure 9. Plot showing the carbon and nitrogen isotope ratios against approximate age for dentine collagen extracted from the M2. The green line indicates the suggested upper limit for δ13C of −20‰ for solely terrestrial diets in prehistoric northern Britain (Bonsall et al. Reference Bonsall, Cook, Pickard, McSweeney, Bartosiewicz, Crombé, Van Strydonck, Sergant, Boudin and Bats2009). Analytical uncertainty is shown at ±0.2‰ (1σ).

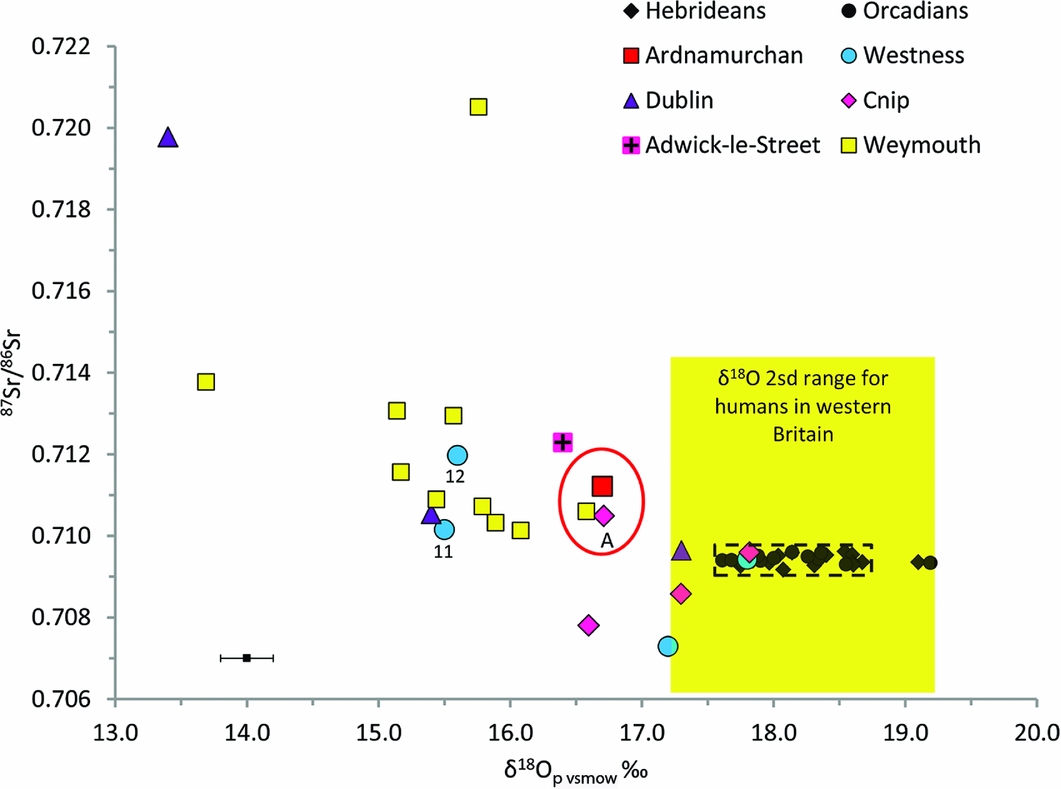

The low oxygen isotope ratio of 16.7‰ shows that the Ardnamurchan individual did not originate from the place of burial on the western seaboard of Britain (Figure 10). Oxygen isotopes also rule out the Northern and Western Isles of Scotland, western Britain and western Ireland. Both the strontium and lead isotopes are indicative of origins in a region of relatively old geology, and thus rule out England and Wales, other regions of young sedimentary rocks, basalts and limestone, and Denmark, which is predominantly limestone overlain by till and hosts a strontium isotope biosphere between 0.7081–0.7111 (Frei & Frei Reference Frei and Frei2011). This would be difficult to reconcile with the Ardnamurchan individual's strontium isotope ratio of 0.7112. The combined evidence, including the very low level of lead exposure experienced by the Ardnamurchan individual (0.4mg/kg), suggests origins in a region of ancient, possibly Precambrian, geology with little or no environmental lead pollution. Given that there are no significant lead deposits in Denmark, southern Norway or western Sweden (Reimann et al. Reference Reimann, Flem, Fabian, Birke, Ladenberger, Négrel, Demetriades and Hoogewerff2012), and that Scandinavia lay outside the Roman Empire—which heralded the advent of increased lead levels in humans in first-millennium AD Britain (Montgomery et al. Reference Montgomery, Chenery, Pashley, Killgrave and Eckardt2010)—lead levels below 0.5mg/kg may indicate Scandinavian origins in British Viking-period burials (Montgomery et al. Reference Montgomery, Grimes, Buckberry, Evans, Richards and Barrett2014). Places consistent with all the isotopic and trace element evidence therefore include eastern Ireland, north-eastern mainland Scotland, Norway and Sweden. Further details and contextualisation of the isotope results can be found in the accompanying online supplementary material.

Figure 10. Enamel strontium and phosphate oxygen isotope data for the Ardnamurchan burial compared to data for other Viking-period burials in Britain and Ireland. The estimated range indicated by the yellow box for biosphere strontium in the Ardnamurchan peninsula is taken from Evans et al. (Reference Evans, Montgomery, Wildman and Boulton2010) and the range (again in the yellow box) of δ18O for western Britain from Evans et al. (Reference Evans, Chenery and Montgomery2012).

Materialising identities

There is clearly much to be gained from a comparison between this boat burial and others across the Scandinavian world (see papers in Crumlin-Pedersen & Thye Reference Crumlin-Pedersen and Thye1995), both in terms of identity and the broader cosmological understandings at work. Here, however, we want to focus on this specific grave, and on what it tells us about the identity of this particular person. Identity is a matter of performance and citation (Butler Reference Butler1993; for discussion of identity in archaeology, see Fowler Reference Fowler, Hicks and Beaudry2010; on Viking funerals and performance, see Price Reference Price2010). It is performative in that it is produced through people's actions, and through their relationships with the world around them. It is not somehow intrinsically held within a person, but rather is an ongoing process of becoming through life, a process that enfolds both the body (Robb & Harris Reference Robb and Harris2013: 16–17) and material things (Harris Reference Harris, Pierce, Russell, Maldonado and Campbell2016). That the dead do not bury themselves is an old archaeological maxim, but neither do the living create identity in isolation. The materiality of bodies and things—whether dead or alive—has a force that cannot be ignored when considering the production of identity. Critical here is the notion of citation, the concept that when people act in certain ways, or deposit certain material things, they bring with them connections to other places, events and people (Butler Reference Butler1993: 13; Jones Reference Jones2007: 80–81).

When we consider this burial, what can we say about identity? At least three terms could potentially be used to describe the deceased: ‘Norse’, ‘warrior’ and ‘high status’. Evidence for the first of these comes from the boat and related connotations of travel and voyaging (cf. Williams Reference Williams, Alexandersson, Andreeff and Bünz2014: 397); from the material culture from Scandinavia and Ireland; and from the surviving teeth. Even though a definitive place of origin cannot be proven from the isotope evidence alone, when combined with the material from the grave itself a Scandinavian homeland is suggested; Ireland cannot, however, be ruled out. The evidence for a warrior identity lies, of course, in the weapons, although this imposes a traditional assumption that grave goods belong to the deceased and directly disclose their identity. Finally, the whole assemblage—the artefacts and their elaborate interment—suggests a notion of high status. None of these categories exist as absolutes, yet they are, however, all materialised and cited through relationships expressed by the material objects in the grave. These identities also emerge in the location of a person's final resting place and reflect the relationships that person may have held with other places and other times while alive.

What about gender? We have no evidence from the body on which to assign this. Although the recovery of the sword and the wider set of grave goods might traditionally suggest that this was the burial of a man (McGuire Reference McGuire, Pierce, Russell, Maldonado and Campbell2016; although see McLeod Reference McLeod2011 for an alternative opinion), any reading remains highly interpretive. A consideration of identity rooted in notions of performativity allows us to engage with the ways in which concepts of masculinity are cited through the weapons in the grave, the absence of jewellery and so on. Whether the body itself would be biologically sexed in the present as male or female is of less importance than the kinds of identity produced through the assembled grave goods. Indeed, perhaps there are material elements here that complicate the narrative we ourselves are weaving. Sickles in burials in Scotland are more often associated with females, although in the Norwegian context Petersen (Reference Petersen1951: 515–16) has noted a majority with males. Furthermore, new work on female Norse warriors also indicates the complexity of gender in this period (Gardela Reference Gardela2013). Assumptions regarding binary Norse gender categories should be approached with caution.

Beyond these major strands, we can tease out further important dimensions through which identity was performed; there are many other objects that embodied other connections, relations and possibilities for practice. The placing and treatment of specific items within different parts of the burial—the sword and axe on the left, the drinking horn on the right, the ladle behind the head—point to potential conceptual schemas or cosmologies materialised in these deliberate choices. Meanwhile, the pan, the hammer and tongs, the strike-a-lights and the whetstone speak to the rhythms of daily life, of cooking and work, just as the sickle links to farming and food production. The importance of repair, of the embodied work of maintaining objects and crafts, is referenced in the bag of rivets and the whetstone. These activities are important elements of the identities that are materially constructed in these acts of deposition: identities of seafaring and farming, of distant journeys and local connections, entwine with those materialised around a hot forge or a domestic hearth. The absent body is made present through the full range of relations disclosed. Similarly, while the isotopes tell us where this person grew up, they also reveal the brief period during their childhood when a marine diet dominated.

It is not only the identity of the dead that is transformed through these performative practices: places are also changed by the links constituted between Norway, the Irish Sea and Ardnamurchan through the material associations engendered in acts of deposition. Just as they speak to us of origins and connections, so these ‘pieces of places’ (sensu Bradley Reference Bradley2000: 88) created associations between Swordle Bay and the broader Norse world. They may have materialised the journeys that the deceased took in life, the narrative of their individual history (Price Reference Price2010: 147) as they travelled from Scandinavia, over the sea and round the Scottish coast, potentially meeting and trading with people from Dublin along the way. New kinds of memory and connectivity are forged, connecting migrant identities to these new places (cf. McGuire Reference McGuire2010: 193; Reference McGuire, Pierce, Russell, Maldonado and Campbell2016). We could use the stable isotope data to speculate further regarding similarities to the female burial A at Cnip (see Figure 10 and online supplementary material) that is of a similar date (Welander et al. Reference Welander, Batey and Cowie1987: 169). Could the occupants of these two burials, who probably grew up in close geographic and chronological proximity, have remained in contact after leaving their homeland? A degree of visual contact was certainly maintained: on a clear day, a view of the Outer Hebrides is possible from Swordle Bay.

We should also remember the other identities performed and transformed here among the people involved in digging the boat-shaped grave, dragging the boat onto the foreshore and burying it, 1000 years ago. It is all too easy to employ clinical archaeological conventions when we discuss the cut of the grave and the deposits therein; the stone lining, the deposition of the body and grave goods. Yet these are not just representative of physical ‘events in time’, but of bodily actions undertaken, of moments of grief and of identities performed. Those undertaking the actions, caught up in the burial, and those watching, were also changed through the memories and connections they made (Williams Reference Williams, Alexandersson, Andreeff and Bünz2014). Price (Reference Price2010) has written of the drama of Viking funerals, and we can imagine this here too. The boat set into the ground, the sword bent, the spear snapped. If the spear and shield were indeed deposited later, this suggests a different kind of relationship was being formed between these objects and the deceased, perhaps specific connections with the living that endured beyond death, the grave site facilitating ‘post-funeral engagements’ (Williams Reference Williams, Alexandersson, Andreeff and Bünz2014: 404).

Assembling places and persons

In the final section, we want to consider an important question: why was this Viking buried here (cf. Williams et al. Reference Williams, Rundkvist and Danielsson2010)? Until very recently, both local and long-distance movement in the region was characterised by sea travel, and Ardnamurchan's place in the wider seaways of the Outer and Inner Hebrides was highly important. The peninsula is a distinctive swathe of land encircled by islands: Mull to the south; Coll and Tiree to the west; the Small Isles of Eigg, Rum and Muck and the Isle of Skye to the north. Various other mainland peninsulas are also visible and easily accessed by sea. For people throughout the past, moving along the west coast by boat, and particularly on the well-travelled route from Scandinavia, via Orkney, to Dublin, Ardnamurchan was a natural stopping point. As we have seen, the material culture in the grave and the isotopic evidence speak to these regional connections, and the Scandinavian influence is underlined by the local place names—including Swordle Bay—that have a Norse connection (Bankier Reference Bankier2006, pers. comm.). Yet these geographic connections could apply anywhere on the peninsula; crucially, our wider work makes it possible to understand why it was here specifically, in Swordle Bay, that this burial was located, for this place enables a citation of relations that are not just geographic but temporal too. Swordle Bay has a rich and deep history of use that would have been clearly visible in medieval times. The large Neolithic chambered cairn of Cladh Aindreis saw repeated moments of intervention from the first burials around 3700 cal BC through the Bronze Age and into the start of the Iron Age (Harris et al. Reference Harris, Cobb, Gray and Richardson2014). It is well attested that the Vikings knew of, respected, accessed, altered, and built mythology around Neolithic and Bronze Age monuments such as at Maes Howe, Orkney, where runic inscriptions and the expansion of the encircling bank suggest significant Viking interaction (Graham-Campbell & Batey Reference Graham-Campbell and Batey1998: 60–61; Artelius Reference Artelius, Fontijn, Louwen, Van Der Vaart and Wentink2013; see also McGuire Reference McGuire, Pierce, Russell, Maldonado and Campbell2016: 79). It seems highly probable that Cladh Aindreis was also the subject of important Viking narratives. Indeed, a Viking Age bead, Irish in type, was found in excavations of a disturbed context within the Neolithic tomb, and the archaeology (although badly damaged by post-medieval digging) suggests deliberate Viking intervention. Further potential links lie in the very stones that fill the boat burial itself, whose shape, geology and size match those from the chambered cairn just a short distance away—the nearest available source of such material.

The answer to the question ‘why here?’ lies in the richness of Swordle Bay. It is, of course, resource-rich in a traditional sense; it is one of the few bays on the northern coast of the peninsula that has a sheltered natural harbour, a fresh water source and good farming land. But it is also rich in a conceptual sense, with a clear and visible ancestry to which the boat burial connected. The use and reuse of older places and older sites of burial is a typical feature of Viking burials and no doubt speaks to a deliberate attempt to gain associations and connections with a new landscape, to appropriate it in new ways, and so create new links and new memories (Williams Reference Williams, Alexandersson, Andreeff and Bünz2014: 398). This burial was therefore able at once to embody the everyday and the exotic, past and present, as well as local, national and international identities.

Conclusion

The Ardnamurchan boat burial represents the first excavation of an intact Viking boat burial by archaeologists on the UK mainland, and it makes a significant addition to our knowledge of burial practices from this period. The uncovering of such a burial also offers opportunities for multi-scalar analysis, from local and regional connections on the one hand, to the momentary act of depositing an object next to a body, or breaking a spear and placing it in the grave on the other. In this article, we have begun to trace some of these scales, including the connections evident to Scandinavia and Ireland in the objects, and how the isotopic profile suggests a varied history of diet and connections away from Swordle Bay. We have also touched on the way the boat burial brings together not only multiple geographic connections, but also some that cross time, reaching back into prehistory and forwards to our work as archaeologists in the present. Much more remains to be said, not least about the ritual process of the funeral and the detailed performances that took place there. Critically, when considering a burial like this, it is essential to remember that each of these objects, and each of these actions, was never isolated, but rather they emerge out of, and help to form, an assemblage that knits together multiple places, people and moments in time.

Acknowledgements

The 2011 excavations were funded by The Universities of Newcastle and Manchester and the Leverhulme Trust. The post-excavation analysis, isotopic work and conservation were funded by Viking River Cruises and the Strathmartine Trust, with the conservation being carried out by Pieta Greaves, then of AOC Archaeology, with further consultation from Will Murray of the Scottish Conservation Studio. Permission to excavate was granted by the Ardnamurchan Estate. The lead, strontium and oxygen isotope and concentration data were produced at the British Geological Survey, Keyworth, by Vanessa Pashley, Jane Evans, Simon Chenery and Hilary Sloane, and the carbon and nitrogen isotopes by Andy Gledhill at the University of Bradford. Thanks go to all of the staff and students who have worked on the project since 2006. We are also grateful to Irene Garcia Rovira for drawing Figures 4 and 5, and to the reviewers for their helpful comments.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2016.222