To the Editor—Bacterial antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has emerged worldwide as one of the leading public health threats of the 21st century. Reference Murray, Ikuta and Sharara1 A 2016 review on antimicrobial resistance commissioned by the UK government estimated that global AMR deaths could reach 10 million people per year by 2050. Reference O’Neill2 Decreasing unnecessary antimicrobial use reduces the risk of antibiotic resistance but also reduces unnecessary side effects and cost; furthermore it helps maintain a healthy individual human microbiome. Reference Patangia, Anthony Ryan, Dempsey, Paul Ross and Stanton3 The West Yorkshire Health and Care Partnership (WYHCP) AMR program aims to achieve at least a 10% reduction in antimicrobial resistance infections by 2024. Reference West and Michie4 Behavioral change by the general public is a key part of achieving this goal. The (C), opportunity (O), and motivation (M) as three key factors capable of changing behavior (B) (ie, COM-B) model of behavioral change conceptualizes how capabilities, opportunities and motivations combine to cause behavior. Reference West and Michie4 Using this model, we designed a study to help develop educational videos for the public—specifically, whiteboard animation videos. These animations are a visually engaging way of presenting complex information, including health topics. Whiteboard animations about healthcare have gained hundreds of millions of views, and there is evidence that they have improved patient understanding of a number of topics. Reference Ciciriello, Johnston and Osborne5

We studied 2 key areas of public behavior: reducing consumption of unnecessary antibiotics and drinking enough fluids daily to help prevent urinary tract infections (UTIs). To inform our study methods, we consulted the Behavioural Science and Insights Unit (UK Health Security Agency). We chose a focus-group workshop study design to produce qualitatively rich data. Convenience sampling was used to recruit a heterogeneous sample of participants for the focus group; initially by approaching students and colleagues within the University of Huddersfield campus, then inviting friends, friends of friends, and family to take part. All interested participants who verbally confirmed that they held no healthcare qualifications were provided or shown written project information, then they were contacted via email with a copy of the project information sheet, workshop details, and a consent form (Appendix 1). Written consent was required to be completed prior to participation and was additionally collected verbally prior to audio-recording their session.

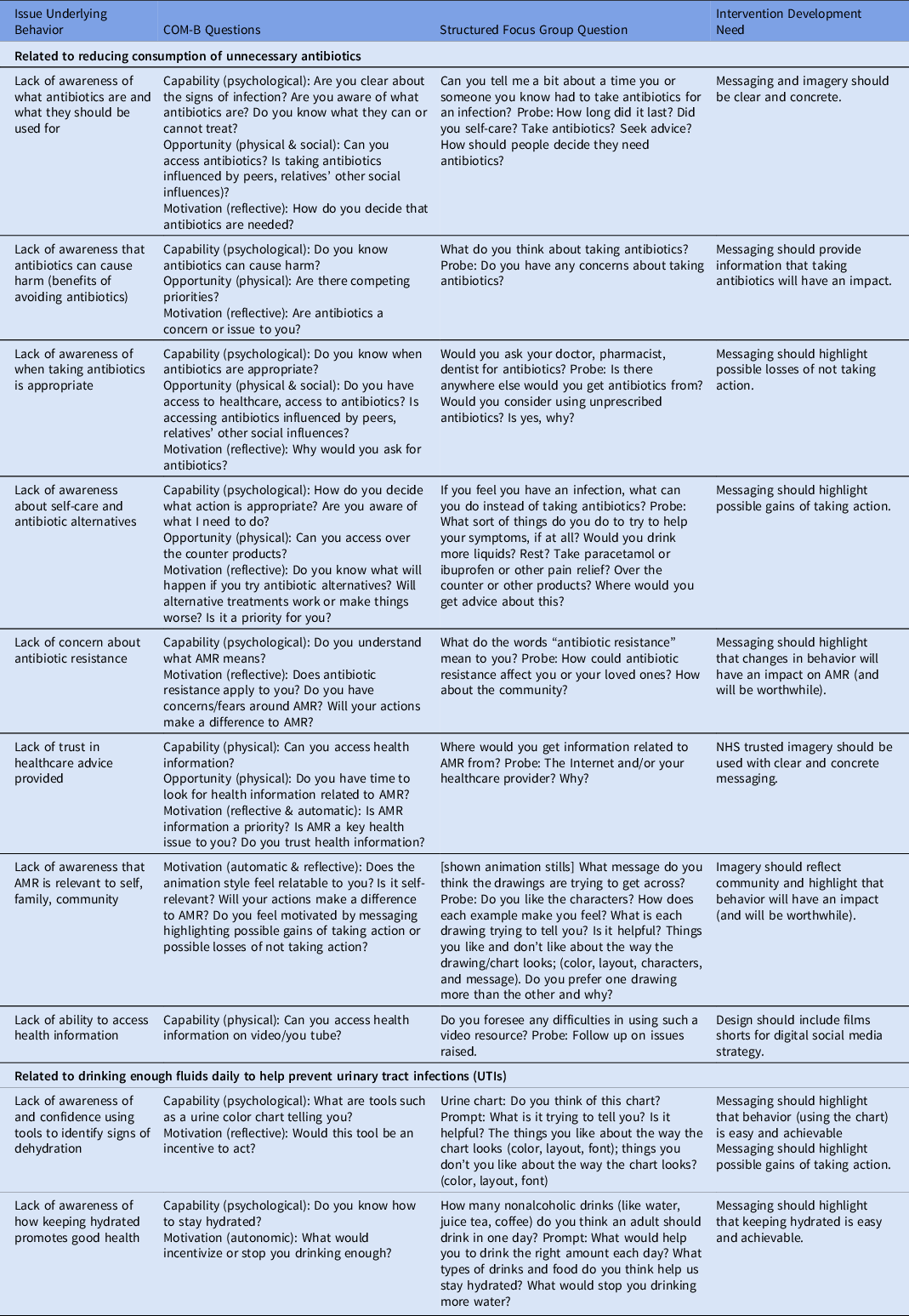

Demographic information was collected from participants via a pseudonymized online questionnaire link, including age, gender, first part of address code, and ethnicity. Using the COM-B model, Reference West and Michie4 we formed a semistructured interview guide (Appendix 2), designed to explore the both the underlying reasons for people’s behavior and how we could change them using animations (Table 1). The questions were developed to ensure the interviewer had various ways to solicit more depth in responses.

Table 1. Focus-Group Questions Developed in Accordance With the COM-B Model, and Corresponding Intervention Considerations After Data Analysis

The study included 6 participants of 3 different ethnicities: African, White British, and White and Black Caribbean. Age categories ranged from <18 years to >60 years; 67% identified as male and 33% identified as female. The focus group was audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, and then analyzed thematically, using Microsoft Excel (Redmond, WA), by independent researchers with expertise in qualitative research (M.B. and M.A.A.). Reference Maguire and Delahunt6

Our data analysis revealed the following 4 themes: (1) Patients would try alternative treatments (eg, paracetamol, lozenges, or honey) before seeking antibiotics from their primary healthcare provider or getting it from other sources (including leftovers from previous infections). (2) Online health information is used as a triage, with uncertainty about the trustworthiness of online sources (other than NHS, BBC news, and medical journals). (3) There is a lack of knowledge about and fear of antibiotic resistance and its impact on individuals and society. (4) There is uncertainty regarding the required amount of fluid intake and the usefulness of using a urine color chart (Appendix 3). However, participants thought the videos were easy to use and could be used for education. Further, the focus-group participants discussed key behaviors driving change. Scripts were designed to motivate listeners about how infection and AMR will affect themselves and others. The scripts emphasized the potential losses if the behavior is unchanged and highlighted the benefits of changing behavior.

Our study informed the production of 2 videos, one outlining the size of the problem of antimicrobial resistance and the behaviors that can prevent it (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XaSCJvYk23s) and another that outlined how to help prevent infections (especially UTIs) by remaining hydrated (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ljdQxkJtdvY). To interpret the study, we must consider its limitations. The study could be expanded to a larger number of participants and could be extended to include vulnerable populations (older adults, non–English-language speakers and low-income groups) most at risk from antibiotic overprescribing and health inequities. The focus group took place during the COVID-19 pandemic, and this and other factors may have introduced bias regarding who decided to participate such as people vulnerable to infection concerned about meeting others, or their caregivers. An evaluation of the videos is still required to measure the attributes they have in changing behavior.

Using the COM-B framework, Reference West and Michie4 we identified important AMR behavioral factors to target: lack of knowledge (of what AMR is and how much fluid to drink daily), emotional response (fear of the damage AMR will do in future), and existing behaviors (trying to find reliable information online, trying alternative treatments before antibiotics). Overall, the coherent evidence regarding efficacy and best practice for educational videos targeting antibiotic behaviors remains limited. Reference Parveen, Garzon-Orjuela, Amin, McHugh and Vellinga7 Indeed, some AMR evidence points to how public education videos should be integrated with antibiotic policies in healthcare. Reference Hawkins, Scott and Montgomery8 It is important to consider how we use the videos (eg, internet upload only or community engagement Reference Appiah, Asamoah-Akuoko and Samman9 ). Evidence regarding AMR education is increasing, and based on user data, studies such as ours help inform the public regarding health-related activities as we try to mobilize forces effectively to avert a major future health crisis from AMR. Reference Courtenay, Castro-Sanchez, Fitzpatrick, Gallagher, Lim and Morris10

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/ash.2023.185

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge and appreciate all the volunteers who participated in this study, as well as NHS colleagues from across the United Kingdom for providing valuable advice and insight. Special thanks are due to the West Yorkshire AMR Steering group (NHS West Yorkshire Integrated Care Board) for their guidance, opinion, and script editing. Ethical approval was obtained from the School of Applied Science, University of Huddersfield (no. SAS-SRIEC-01.6.22-1).

Financial support

No financial support was provided relevant to this article.

Competing interests

All authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.