Background

In the last three years, extensive research has demonstrated the safety and efficacy of COVID-19 (Coronavirus Disease 2019) vaccines. Reference Sharif, Alzahrani, Ahmed and Dey1,Reference Zheng, Shao, Chen, Zhang, Wang and Zhang2 These vaccines have played a critical role in reducing mortality and hospitalization rates. Reference Tenforde, Self and Adams3,Reference Mohammed, Nauman and Paul4 Furthermore, studies have confirmed the value of additional COVID-19 vaccine doses in sustaining immunization effectiveness and guarding against emerging variants. Reference Chenchula, Karunakaran, Sharma and Chavan5,Reference Regev-Yochay, Gonen and Gilboa6 However, post-COVID conditions, commonly known as long COVID, have become a significant concern as growing evidence suggests that a substantial number of individuals continue to experience persistent symptoms and complications long after the acute phase of the illness.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines post-COVID conditions as a vast range of ongoing health problems (e.g., cardiovascular, respiratory, and neuropsychiatric symptoms) that can last for more than 4 weeks after an individual has been infected by severe acute respiratory coronavirus virus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) virus. 7 These conditions can significantly impact individuals’ quality of life, and daily functioning, and pose a considerable burden on the healthcare system. As of January 2023, 28% of individuals who had a previous COVID-19 infection experienced post-COVID conditions. 8 A systematic review published previously demonstrated that receiving at least one dose of Pfizer/BioNTech, Moderna, AstraZeneca, or Janssen vaccines could prevent the occurrence of long COVID symptoms. Reference Marra, Kobayashi and Suzuki9

As vaccination campaigns have progressed, the majority of people have received more than one dose of COVID-19 vaccines. However, their effectiveness in preventing post-COVID conditions among fully vaccinated individuals remains an unresolved question. Reference Arnold, Milne, Samms, Stadon, Maskell and Hamilton10,Reference Venkatesan11 The vaccine effectiveness (VE) against post-COVID symptoms might vary depending on the number of vaccine doses people have received. Hence, our objective was to conduct a literature review on the effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines, specifically examining the impact of receiving two or more doses of these vaccines in preventing post-COVID conditions. By pooling the findings of published studies, we aimed to provide more accurate estimates of vaccine effectiveness.

Methods

Systematic literature review and inclusion and exclusion criteria

This review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis statement Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman12 and the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology guidelines Reference Stroup, Berlin and Morton13 and was registered on Prospero (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/) on 5/24/2023 (registration number CRD42023429149). Institutional Review Board approval was not required. Inclusion criteria for studies in this systematic review were as follows: original research manuscripts; published in peer-reviewed, scientific journals; involved fully vaccinated (at least two doses of COVID-19 vaccines [mRNA, or vectorial or inactivated viral vaccine], with exception of one dose for Janssen [Ad26.COV2.S] vaccine), and unvaccinated individuals; evaluated the long-term effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccine; and observational study design. Post-COVID condition (also known as long COVID) was defined as a wide range of health symptoms that are present four or more weeks after COVID-19 infection. 7 The literature search included studies from December 1, 2019 to June 2, 2023. Editorials, commentaries, reviews, study protocols, studies analyzing one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, and studies in the pediatric population were excluded. Studies comparing partially vaccinated (one dose of COVID-19 vaccine) with unvaccinated individuals were excluded. Studies without a comparison between vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals (or other vaccinated control groups) were also excluded.

Search strategy

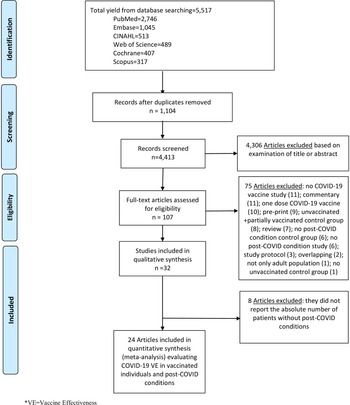

We performed literature searches in PubMed, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health, Embase (Elsevier Platform), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Scopus (which includes EMBASE abstracts), and Web of Science. The entire search strategy is described in Supplementary Appendix 1. After applying the exclusion criteria, we reviewed 107 papers, out of which 32 met the inclusion criteria and were included in the systematic literature review (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Literature search for articles on the COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness in post-COVID conditions.

Data abstraction and quality assessment

Titles and abstracts of all articles were screened to assess whether they met the inclusion criteria. Abstract screening was performed by one reviewer (ARM). Of ten independent reviewers (ARM, GYC, IP, JT, MA, MCG, MH, SH, TK, and VL), two independently abstracted data for each article using a standardized abstraction form. Reviewers resolved disagreements by consensus.

The reviewers abstracted data on study design, population and location, study period (months) and calendar time, demographic and characteristics of participants, and the types of COVID-19 vaccine if available. Post-COVID conditions were considered the primary outcome to calculate VE after at least two doses of a COVID-19 vaccine. Eleven corresponding authors were contacted for additional information, and four were able to provide additional information regarding the number of individuals with and without post-COVID conditions in both fully vaccinated and unvaccinated groups. Reference Mohammed, Nauman and Paul4–Reference Kahlert, Strahm and Güsewell17 Risk of bias was assessed using the Downs and Black scale. Reference Downs and Black18 Reviewers answered all original questions from this scale except for question #27 (a single item on the Power subscale scored 0–5), which was changed to a yes or no. Two authors performed component quality analysis independently, reviewed all inconsistent assessments, and resolved disagreements by consensus. Reference Alderson19

Statistical analysis

To perform a meta-analysis of the extracted data, we calculated the pooled diagnostic odds ratio (DOR) for post-COVID conditions between fully vaccinated and unvaccinated individuals. Vaccine effectiveness was estimated as 100% x (1-DOR). We performed stratified analyses by the timing of the COVID-19 vaccine (i.e., those with COVID-19 vaccines before or after COVID-19 diagnosis, those with COVID-19 vaccines before COVID-19 diagnosis, those with COVID-19 vaccines after COVID-19 diagnosis, and those with COVID-19 vaccines before COVID-19 diagnosis during the Omicron variant era), and between those vaccinated with a first booster dose and unvaccinated individuals. We performed statistical analysis using R version 4.1.0 with mada package version 0.5.8. Reference Doebler and Sousa-Pinto20 Analogous to the meta-analysis of the odds ratio methods for the DOR, an estimator of random-effects model following the approach of DerSimonian and Laird is provided by the mada package. Reference Doebler and Sousa-Pinto20 For our meta-analysis of VE estimates against post-COVID conditions, we used a bivariate random-effects model, adopting a similar concept of performing the diagnostic accuracy. This enabled simultaneous pooling of sensitivity and specificity with mixed-effect linear modeling while allowing for the trade-off between them. Reference Reitsma, Glas, Rutjes, Scholten, Bossuyt and Zwinderman21,Reference Goto, Ohl, Schweizer and Perencevich22 Heterogeneity between studies was evaluated with I2 estimation and the Cochran Q statistic test. Publication bias was assessed using the Egger test with R version 4.1.0 with metafor package Reference Viechtbauer23 .

Results

Characteristics of included studies

Thirty-two studies met the inclusion criteria Reference Emecen, Keskin and Turunc14–Reference Kahlert, Strahm and Güsewell17,Reference Alghamdi, Alrashed, Jawhari and Abdel-Moneim24–Reference Zisis, Durieux, Mouchati, Perez and McComsey51 and were included in the final review (Table 1). All studies were non-randomized Reference Emecen, Keskin and Turunc14–Reference Kahlert, Strahm and Güsewell17,Reference Alghamdi, Alrashed, Jawhari and Abdel-Moneim24–Reference Zisis, Durieux, Mouchati, Perez and McComsey51 ; of these, fourteen were retrospective cohort studies, Reference Hernández-Aceituno, García-Hernández and Larumbe-Zabala15,Reference Al-Aly, Bowe and Xie25,Reference Ayoubkhani, Bosworth and King29–Reference Ballouz, Menges and Kaufmann31,Reference Hastie, Lowe and McAuley35,Reference Ioannou, Baraff and Fox36,Reference Meza-Torres, Delanerolle and Okusi40,Reference Pinato, Ferrante and Aguilar-Company44–Reference Selvaskandan, Nimmo and Savino46,Reference Tannous, Pan and Potter48,Reference Taquet, Dercon and Harrison49,Reference Zisis, Durieux, Mouchati, Perez and McComsey51 nine were prospective cohort studies Reference Emecen, Keskin and Turunc14,Reference van der Maaden, Mutubuki and de Bruijn16,Reference Arjun, Singh and Pal28,Reference Brunvoll, Nygaard and Fagerland32,Reference Hajjaji, Lepoutre and Lakhdar34,Reference Jassat, Mudara and Vika37,Reference Kuodi, Gorelik and Zayyad38,Reference Mohr, Plumb and Harland41,Reference Thaweethai, Jolley and Karlson50 , five were cross-sectional studies, Reference Kahlert, Strahm and Güsewell17,Reference Alghamdi, Alrashed, Jawhari and Abdel-Moneim24,Reference Nehme, Braillard and Chappuis42,Reference Perlis, Santillana and Ognyanova43,Reference Senjam, Balhara and Kumar47 and four were case-control studies. Reference Antonelli, Penfold and Merino26,Reference Antonelli, Pujol, Spector, Ourselin and Steves27,Reference El Otmani, Nabili, Berrada, Bellakhdar, El Moutawakil and Abdoh Rafai33,Reference Marra, Sampaio and Ozahata39 One of the cross-sectional studies was also within a prospective cohort study. Reference Kahlert, Strahm and Güsewell17 More than half of these studies (22 out of 32) evaluated the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine. Reference Emecen, Keskin and Turunc14–Reference Kahlert, Strahm and Güsewell17,Reference Alghamdi, Alrashed, Jawhari and Abdel-Moneim24–Reference Antonelli, Penfold and Merino26,Reference Ayoubkhani, Bosworth and King29–Reference Ballouz, Menges and Kaufmann31,Reference Ioannou, Baraff and Fox36–Reference Marra, Sampaio and Ozahata39,Reference Mohr, Plumb and Harland41–Reference Richard, Pollett and Fries45,Reference Tannous, Pan and Potter48–Reference Thaweethai, Jolley and Karlson50 Sixteen analyzed the Moderna vaccine, Reference Hernández-Aceituno, García-Hernández and Larumbe-Zabala15–Reference Kahlert, Strahm and Güsewell17,Reference Al-Aly, Bowe and Xie25,Reference Antonelli, Penfold and Merino26,Reference Ayoubkhani, Bosworth and King29,Reference Ballouz, Menges and Kaufmann31,Reference Ioannou, Baraff and Fox36,Reference Mohr, Plumb and Harland41–Reference Richard, Pollett and Fries45,Reference Tannous, Pan and Potter48–Reference Thaweethai, Jolley and Karlson50 twelve analyzed the Janssen vaccine, Reference Hernández-Aceituno, García-Hernández and Larumbe-Zabala15,Reference van der Maaden, Mutubuki and de Bruijn16,Reference Al-Aly, Bowe and Xie25,Reference Ballouz, Menges and Kaufmann31,Reference Jassat, Mudara and Vika37,Reference Marra, Sampaio and Ozahata39,Reference Perlis, Santillana and Ognyanova43–Reference Richard, Pollett and Fries45,Reference Tannous, Pan and Potter48–Reference Thaweethai, Jolley and Karlson50 ten analyzed the AstraZeneca vaccine, Reference Hernández-Aceituno, García-Hernández and Larumbe-Zabala15,Reference van der Maaden, Mutubuki and de Bruijn16,Reference Alghamdi, Alrashed, Jawhari and Abdel-Moneim24,Reference Antonelli, Penfold and Merino26,Reference Arjun, Singh and Pal28,Reference Ayoubkhani, Bosworth and King29,Reference El Otmani, Nabili, Berrada, Bellakhdar, El Moutawakil and Abdoh Rafai33,Reference Marra, Sampaio and Ozahata39,Reference Pinato, Ferrante and Aguilar-Company44,Reference Tannous, Pan and Potter48 two the CoronaVac vaccine, Reference Emecen, Keskin and Turunc14,Reference Marra, Sampaio and Ozahata39 one the Covaxin vaccine, Reference Arjun, Singh and Pal28 one the Sinopharm vaccine, Reference El Otmani, Nabili, Berrada, Bellakhdar, El Moutawakil and Abdoh Rafai33 and one analyzed the Gamaleya vaccine. Reference Hernández-Aceituno, García-Hernández and Larumbe-Zabala15 There were no published studies that evaluated post-COVID conditions as an outcome of bivalent COVID-19 vaccines.

Table 1. Summary of characteristics of studies included in the systematic literature review

D&B score, Downs and Black score; ICD-10, 10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases; WHO, World Health Organization; NR, Not reported.

*[From Kuodi 2022 study] – At the time of data collection, very few individuals had received a third dose, and those who did were recorded as two doses.

One-quarter of the studies included in our review were conducted in the United States (8 studies). Reference Al-Aly, Bowe and Xie25,Reference Ioannou, Baraff and Fox36,Reference Mohr, Plumb and Harland41,Reference Perlis, Santillana and Ognyanova43,Reference Richard, Pollett and Fries45,Reference Tannous, Pan and Potter48,Reference Thaweethai, Jolley and Karlson50,Reference Zisis, Durieux, Mouchati, Perez and McComsey51 Seven studies were performed in the United Kingdom, Reference Antonelli, Penfold and Merino26,Reference Antonelli, Pujol, Spector, Ourselin and Steves27,Reference Ayoubkhani, Bosworth and King29,Reference Meza-Torres, Delanerolle and Okusi40,Reference Pinato, Ferrante and Aguilar-Company44,Reference Selvaskandan, Nimmo and Savino46,Reference Taquet, Dercon and Harrison49 three in Switzerland, Reference Kahlert, Strahm and Güsewell17,Reference Ballouz, Menges and Kaufmann31,Reference Nehme, Braillard and Chappuis42 two in India, Reference Arjun, Singh and Pal28,Reference Senjam, Balhara and Kumar47 and one of each was performed in Brazil, Reference Marra, Sampaio and Ozahata39 France, Reference Hajjaji, Lepoutre and Lakhdar34 Israel, Reference Kuodi, Gorelik and Zayyad38 Italy, Reference Azzolini, Levi and Sarti30 Morocco, Reference El Otmani, Nabili, Berrada, Bellakhdar, El Moutawakil and Abdoh Rafai33 Netherlands, Reference van der Maaden, Mutubuki and de Bruijn16 Norway, Reference Brunvoll, Nygaard and Fagerland32 Saudi Arabia, Reference Alghamdi, Alrashed, Jawhari and Abdel-Moneim24 Scotland, Reference Hastie, Lowe and McAuley35 South Africa, Reference Jassat, Mudara and Vika37 Spain, Reference Hernández-Aceituno, García-Hernández and Larumbe-Zabala15 and Turkey. Reference Emecen, Keskin and Turunc14 All studies were performed between February 2020 and April 2023. Reference Emecen, Keskin and Turunc14–Reference Kahlert, Strahm and Güsewell17,Reference Alghamdi, Alrashed, Jawhari and Abdel-Moneim24–Reference Zisis, Durieux, Mouchati, Perez and McComsey51 The study duration varied from 1 to 29 months.

In our qualitative analysis, thirty-two studies, including 775,931 individuals, evaluated the effect of vaccination among fully vaccinated individuals and unvaccinated individuals on post-COVID conditions. Reference Emecen, Keskin and Turunc14–Reference Kahlert, Strahm and Güsewell17,Reference Alghamdi, Alrashed, Jawhari and Abdel-Moneim24–Reference Zisis, Durieux, Mouchati, Perez and McComsey51 Twenty studies evaluated VE in individuals vaccinated only before COVID-19 infection, Reference Emecen, Keskin and Turunc14–Reference van der Maaden, Mutubuki and de Bruijn16,Reference Al-Aly, Bowe and Xie25–Reference Antonelli, Pujol, Spector, Ourselin and Steves27,Reference Ayoubkhani, Bosworth and King29–Reference Ballouz, Menges and Kaufmann31,Reference Ioannou, Baraff and Fox36,Reference Kuodi, Gorelik and Zayyad38,Reference Marra, Sampaio and Ozahata39,Reference Mohr, Plumb and Harland41,Reference Perlis, Santillana and Ognyanova43,Reference Pinato, Ferrante and Aguilar-Company44,Reference Senjam, Balhara and Kumar47–Reference Zisis, Durieux, Mouchati, Perez and McComsey51 three studies evaluated VE for post-COVID conditions among those who were vaccinated after COVID-19 infection, Reference Brunvoll, Nygaard and Fagerland32,Reference El Otmani, Nabili, Berrada, Bellakhdar, El Moutawakil and Abdoh Rafai33,Reference Nehme, Braillard and Chappuis42 four studies evaluated VE among those who were vaccinated before and after COVID-19 infection, Reference Kahlert, Strahm and Güsewell17,Reference Jassat, Mudara and Vika37,Reference Meza-Torres, Delanerolle and Okusi40,Reference Richard, Pollett and Fries45 and five studies evaluated VE but did not specify the timing of the vaccine Reference Alghamdi, Alrashed, Jawhari and Abdel-Moneim24,Reference Arjun, Singh and Pal28,Reference Hajjaji, Lepoutre and Lakhdar34,Reference Hastie, Lowe and McAuley35,Reference Selvaskandan, Nimmo and Savino46 . All 32 studies evaluated VE with at least two doses of a COVID-19 vaccine. Reference Emecen, Keskin and Turunc14–Reference van der Maaden, Mutubuki and de Bruijn16,Reference Viechtbauer23–Reference Zisis, Durieux, Mouchati, Perez and McComsey51 Three studies evaluated vaccinated individuals with three doses of vaccine. Reference Azzolini, Levi and Sarti30,Reference Ballouz, Menges and Kaufmann31,Reference Marra, Sampaio and Ozahata39 While eight of 32 studies reported data during Omicron variant era, Reference Hernández-Aceituno, García-Hernández and Larumbe-Zabala15,Reference Kahlert, Strahm and Güsewell17,Reference Antonelli, Pujol, Spector, Ourselin and Steves27,Reference Azzolini, Levi and Sarti30,Reference Ballouz, Menges and Kaufmann31,Reference Marra, Sampaio and Ozahata39,Reference Perlis, Santillana and Ognyanova43,Reference Thaweethai, Jolley and Karlson50 24 studies took place before Omicron variant era. Reference Emecen, Keskin and Turunc14,Reference van der Maaden, Mutubuki and de Bruijn16,Reference Alghamdi, Alrashed, Jawhari and Abdel-Moneim24–Reference Antonelli, Penfold and Merino26,Reference Arjun, Singh and Pal28,Reference Ayoubkhani, Bosworth and King29,Reference Brunvoll, Nygaard and Fagerland32–Reference Kuodi, Gorelik and Zayyad38,Reference Meza-Torres, Delanerolle and Okusi40–Reference Nehme, Braillard and Chappuis42,Reference Pinato, Ferrante and Aguilar-Company44–Reference Taquet, Dercon and Harrison49,Reference Zisis, Durieux, Mouchati, Perez and McComsey51

Each study adopted different definitions for post-COVID conditions (Table 1). Post-COVID conditions were defined as symptoms lasting more than 4 weeks in thirteen studies, Reference Hernández-Aceituno, García-Hernández and Larumbe-Zabala15,Reference Kahlert, Strahm and Güsewell17,Reference Al-Aly, Bowe and Xie25–Reference Arjun, Singh and Pal28,Reference Azzolini, Levi and Sarti30,Reference Marra, Sampaio and Ozahata39,Reference Meza-Torres, Delanerolle and Okusi40,Reference Richard, Pollett and Fries45,Reference Senjam, Balhara and Kumar47,Reference Tannous, Pan and Potter48,Reference Zisis, Durieux, Mouchati, Perez and McComsey51 more than 12 weeks in nine studies, Reference van der Maaden, Mutubuki and de Bruijn16,Reference Ayoubkhani, Bosworth and King29,Reference Brunvoll, Nygaard and Fagerland32,Reference El Otmani, Nabili, Berrada, Bellakhdar, El Moutawakil and Abdoh Rafai33,Reference Hastie, Lowe and McAuley35–Reference Kuodi, Gorelik and Zayyad38,Reference Selvaskandan, Nimmo and Savino46 and more than 6 months in seven studies. Reference Emecen, Keskin and Turunc14,Reference Alghamdi, Alrashed, Jawhari and Abdel-Moneim24,Reference Ballouz, Menges and Kaufmann31,Reference Hajjaji, Lepoutre and Lakhdar34,Reference Nehme, Braillard and Chappuis42,Reference Taquet, Dercon and Harrison49,Reference Thaweethai, Jolley and Karlson50 . One study defined symptoms as more than 6 weeks, Reference Mohr, Plumb and Harland41 one study defined symptoms as more than 8 weeks as a post-COVID condition Reference Perlis, Santillana and Ognyanova43 , and one study did not report the duration of symptoms. Reference Pinato, Ferrante and Aguilar-Company44 All studies used at least one of the common symptoms (details shown in Table 1) to make a diagnosis of a post-COVID condition. Reference Emecen, Keskin and Turunc14–Reference van der Maaden, Mutubuki and de Bruijn16,Reference Viechtbauer23–Reference Zisis, Durieux, Mouchati, Perez and McComsey51 Nearly three-quarters of the included studies (22 studies) showed that vaccination was protective against post-COVID symptoms. Reference Emecen, Keskin and Turunc14,Reference van der Maaden, Mutubuki and de Bruijn16,Reference Al-Aly, Bowe and Xie25–Reference Antonelli, Pujol, Spector, Ourselin and Steves27,Reference Ayoubkhani, Bosworth and King29–Reference Brunvoll, Nygaard and Fagerland32,Reference Hastie, Lowe and McAuley35,Reference Ioannou, Baraff and Fox36,Reference Kuodi, Gorelik and Zayyad38,Reference Marra, Sampaio and Ozahata39,Reference Mohr, Plumb and Harland41–Reference Richard, Pollett and Fries45,Reference Senjam, Balhara and Kumar47,Reference Tannous, Pan and Potter48,Reference Thaweethai, Jolley and Karlson50,Reference Zisis, Durieux, Mouchati, Perez and McComsey51 Nine studies did not report any benefit of COVID-19 vaccination in reducing post-COVID condition symptoms, Reference Hernández-Aceituno, García-Hernández and Larumbe-Zabala15,Reference Kahlert, Strahm and Güsewell17,Reference Alghamdi, Alrashed, Jawhari and Abdel-Moneim24,Reference Arjun, Singh and Pal28,Reference El Otmani, Nabili, Berrada, Bellakhdar, El Moutawakil and Abdoh Rafai33,Reference Hajjaji, Lepoutre and Lakhdar34,Reference Jassat, Mudara and Vika37,Reference Meza-Torres, Delanerolle and Okusi40,Reference Taquet, Dercon and Harrison49 and one study did not report any statistical analysis of effectiveness. Reference Selvaskandan, Nimmo and Savino46

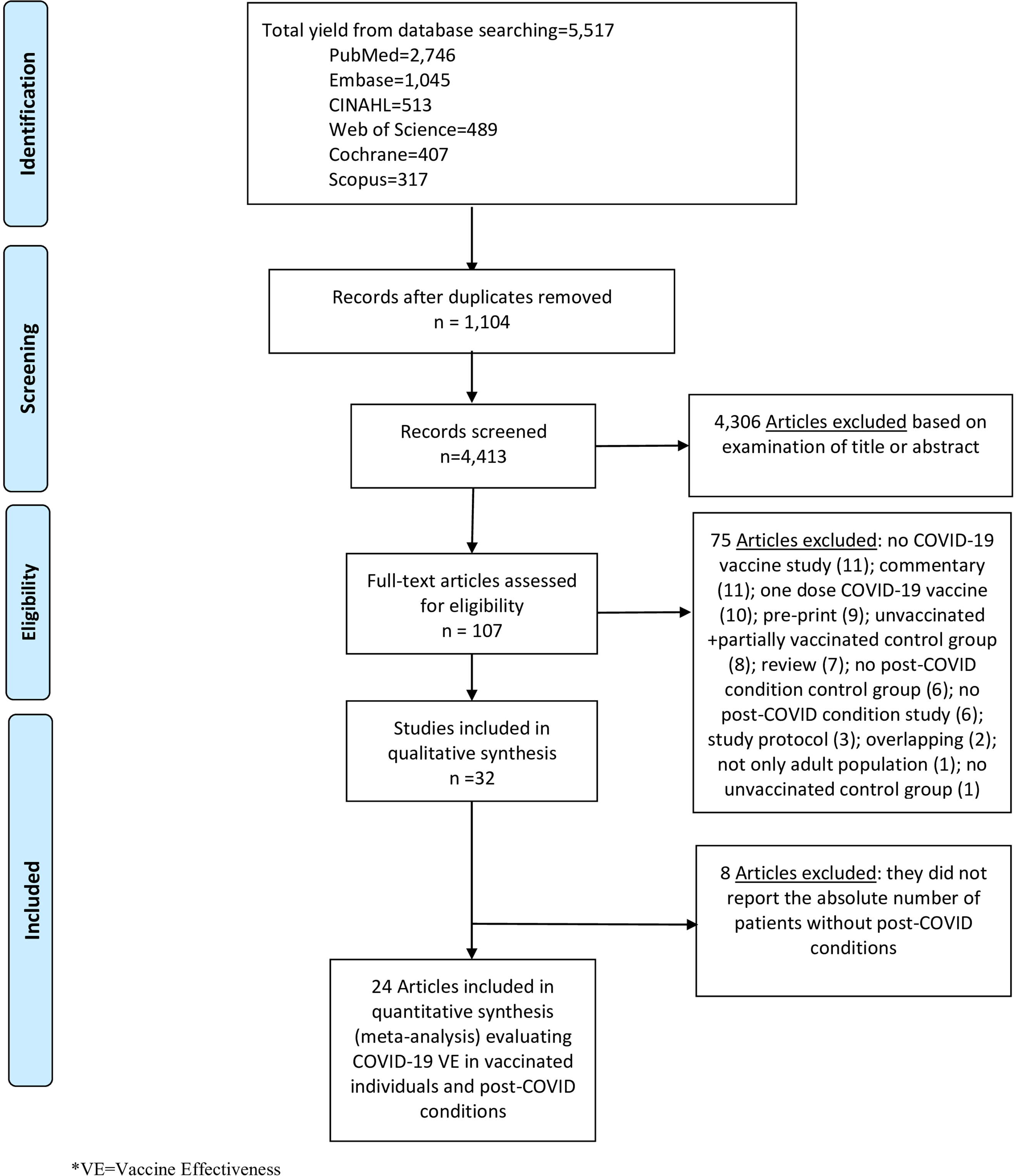

Overall, twenty-four studies, including 620,221 individuals, evaluated post-COVID conditions among those who received at least two doses of COVID-19 vaccine before or after COVID-19 infection (Table 2) and were included in the meta-analysis. Reference Emecen, Keskin and Turunc14–Reference Kahlert, Strahm and Güsewell17,Reference Ayoubkhani, Bosworth and King29–Reference Ballouz, Menges and Kaufmann31,Reference El Otmani, Nabili, Berrada, Bellakhdar, El Moutawakil and Abdoh Rafai33,Reference Hajjaji, Lepoutre and Lakhdar34,Reference Ioannou, Baraff and Fox36–Reference Richard, Pollett and Fries45,Reference Senjam, Balhara and Kumar47–Reference Zisis, Durieux, Mouchati, Perez and McComsey51 The pooled prevalence of post-COVID conditions was 11.8% among those who were unvaccinated and 5.3% among those who received at least two doses. The pooled DOR for post-COVID conditions among individuals vaccinated with two doses was 0.680 (95% CI: 0.523–0.885) with an estimated VE of 32.0% (95% CI: 11.5%–47.7%) (Figure 2). Of the twenty-four studies, twenty-one evaluated post-COVID conditions in individuals who received the COVID-19 vaccine before infection. Reference Emecen, Keskin and Turunc14–Reference Kahlert, Strahm and Güsewell17,Reference Ayoubkhani, Bosworth and King29–Reference Ballouz, Menges and Kaufmann31,Reference Ioannou, Baraff and Fox36–Reference Mohr, Plumb and Harland41,Reference Perlis, Santillana and Ognyanova43–Reference Richard, Pollett and Fries45,Reference Senjam, Balhara and Kumar47–Reference Zisis, Durieux, Mouchati, Perez and McComsey51 The DOR was 0.631 (95% CI: 0.518–0.769) (Supplementary Appendix 2), and the estimated VE was 36.9% (95% CI: 23.1%–48.2%) (Table 2). There were five papers that evaluated post-COVID conditions for those who received the vaccine after infection. Reference Kahlert, Strahm and Güsewell17,Reference El Otmani, Nabili, Berrada, Bellakhdar, El Moutawakil and Abdoh Rafai33,Reference Jassat, Mudara and Vika37,Reference Meza-Torres, Delanerolle and Okusi40,Reference Nehme, Braillard and Chappuis42 The DOR was 1.303 (95% CI: 0.890–1.907) (Supplementary Appendix 3), and it was not possible to estimate VE because it did not prevent post-COVID condition (Table 2). There were seven studies that evaluated post-COVID conditions for those who received the COVID-19 vaccine only before infection during the Omicron variant era. Reference Hernández-Aceituno, García-Hernández and Larumbe-Zabala15,Reference Kahlert, Strahm and Güsewell17,Reference Azzolini, Levi and Sarti30,Reference Ballouz, Menges and Kaufmann31,Reference Marra, Sampaio and Ozahata39,Reference Perlis, Santillana and Ognyanova43,Reference Thaweethai, Jolley and Karlson50 The DOR was 0.684 (95% CI: 0.542–0.862) (Supplementary Appendix 4), and the estimated VE was 31.6% (95% CI: 13.8%–45.8%) (Table 2). There were three studies that evaluated post-COVID conditions for those who received the additional booster dose vaccine only before infection. Reference Azzolini, Levi and Sarti30,Reference Ballouz, Menges and Kaufmann31,Reference Marra, Sampaio and Ozahata39 The DOR was 0.313 (95% CI: 0.278–0.353) (Supplementary Appendix 5), and the estimated VE was 68.7% (95% CI: 64.7%–72.2%) (Table 2). Because there were no studies evaluating post-COVID conditions for those who received two doses of each specific type of COVID-19 vaccine (mRNA or viral vector or inactivated viral vaccine), we did not perform a stratified analysis. The results of meta-analyses were homogeneous for studies evaluating post-COVID conditions in individuals who received the COVID-19 vaccine before or after COVID-19 infection (heterogeneity p = 0.89, I 2 = 0%), and homogenous for studies evaluating post-COVID conditions in individuals receiving vaccine before infection (heterogeneity p = 0.62, I 2 = 0%), and also homogenous for studies evaluating post-COVID conditions in individuals receiving vaccine after infection (heterogeneity p = 0.29, I 2 = 19.9%), respectively. There was no evidence for publication bias among the 24 studies included in the meta-analysis Reference Emecen, Keskin and Turunc14–Reference Kahlert, Strahm and Güsewell17,Reference Ayoubkhani, Bosworth and King29–Reference Ballouz, Menges and Kaufmann31,Reference El Otmani, Nabili, Berrada, Bellakhdar, El Moutawakil and Abdoh Rafai33,Reference Hajjaji, Lepoutre and Lakhdar34,Reference Ioannou, Baraff and Fox36–Reference Richard, Pollett and Fries45,Reference Senjam, Balhara and Kumar47–Reference Zisis, Durieux, Mouchati, Perez and McComsey51 (p = 0.71).

Table 2. Subset analyses evaluating COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness among post-COVID conditions in individuals who received COVID-19 vaccine before or after COVID-19 infection

CI, Confidence Interval.

*Vaccine Effectiveness was estimated as 100% × (1-DOR).

**There is overlapping (VE for post-COVID condition who got COVID-19 vaccine before and after COVID-19 infection) in three of the studies [Jassat 2023, Kahlert 2023 and Meza-Torres 2022]. Reference Kahlert, Strahm and Güsewell17,Reference Jassat, Mudara and Vika37,Reference Meza-Torres, Delanerolle and Okusi40

***Imbalance of studies: one of the five studies with 390,563 participants [Mezza-Torres 2022] Reference Meza-Torres, Delanerolle and Okusi40 , representing 98.6% of the total participants from the COVID-19 vaccine studies after COVID-19 infection.

Figure 2. Forest plot of COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness among post-COVID conditions in individuals who received COVID-19 vaccine before or after COVID-19 infection. Diagnostic odds ratios (DOR) were determined with the DerSimonian and Laird random-effects method. Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval.

Regarding the quality assessment scores of the 32 included studies, more than three-quarters of the studies (28 studies) were considered good quality (19–23 of 28 possible points) as per the Downs and Black quality tool. Reference Emecen, Keskin and Turunc14–Reference Kahlert, Strahm and Güsewell17,Reference Al-Aly, Bowe and Xie25–Reference Brunvoll, Nygaard and Fagerland32,Reference Hajjaji, Lepoutre and Lakhdar34–Reference Mohr, Plumb and Harland41,Reference Perlis, Santillana and Ognyanova43–Reference Richard, Pollett and Fries45,Reference Senjam, Balhara and Kumar47–Reference Zisis, Durieux, Mouchati, Perez and McComsey51 Three studies were considered fair (14–18 points), Reference Alghamdi, Alrashed, Jawhari and Abdel-Moneim24,Reference El Otmani, Nabili, Berrada, Bellakhdar, El Moutawakil and Abdoh Rafai33,Reference Nehme, Braillard and Chappuis42 and one study was considered to be of poor quality (≤13 points). Reference Selvaskandan, Nimmo and Savino46

Discussion

This systematic literature review and meta-analysis suggest that the pooled prevalence of post-COVID conditions was 11.8% among those unvaccinated and 5.3% among those individuals fully vaccinated. The VE of fully vaccinated individuals against post-COVID conditions was not high at approximately 30%; however, the prevalence of post-COVID conditions was lower with a statistically significant difference in fully vaccinated individuals. The stratified analysis showed a significant reduction in post-COVID conditions during the Omicron variant era, and the vaccine should be offered to unvaccinated individuals who have not had COVID-19 yet. Given VE against post-COVID conditions increased with an additional dose of the COVID-19 vaccine, individuals who have not received a booster should be encouraged to get one. There was no protection against post-COVID conditions observed if COVID-19 vaccines were given after COVID-19 infection.

With the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, a considerable proportion of individuals who have recovered from COVID-19 infection have long-term symptoms involving multiple organs and systems. Reference Huang, Li and Gu52,Reference Groff, Sun and Ssentongo53 The percentage of individuals who have had COVID and reported post-COVID condition symptoms declined from 19% in June 2022 to 11% in January 2023 8 . A systematic review including 57 studies reported that more than half of COVID-19 survivors experienced persistent post-COVID condition symptoms 6 months after recovery. Reference Groff, Sun and Ssentongo53 The present systematic review showed a relatively low prevalence of post-COVID conditions; this is likely because most individuals included in our studies were non-hospitalized individuals and we are presently in the Omicron variant era. Reference Kahlert, Strahm and Güsewell17,Reference Azzolini, Levi and Sarti30,Reference Ballouz, Menges and Kaufmann31,Reference Jassat, Mudara and Vika37,Reference Marra, Sampaio and Ozahata39,Reference Thaweethai, Jolley and Karlson50,Reference Perlis, Santillana and Ognyanova54 Previous studies suggested that the Delta and Omicron variants caused less systemic inflammatory processes, severe illness, or death, resulting in less severe long COVID symptoms than the wild-type variant (Wuhan). Reference Antonelli, Pujol, Spector, Ourselin and Steves27,Reference Fernández-de-las-Peñas, Cancela-Cilleruelo and Rodríguez-Jiménez55

Currently, there are no standardized criteria for diagnosing and categorizing post-COVID conditions. Another recent systematic literature review found substantial heterogeneity in defining post-COVID conditions in the published studies, with almost two-thirds (65%) not complying with the definitions from the CDC, the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), or WHO (World Health Organization). Reference Chaichana, Man and Chen56 This variability in definitions across studies can affect the comparability and generalizability of findings. The studies included in our systematic review used a variety of symptoms and durations to make a diagnosis of post-COVID conditions. The most common symptoms described were fatigue or muscle weakness, persistent muscle pain, anxiety, memory problems, sleep problems, and shortness of breath. Reference Huang, Li and Gu52,Reference Groff, Sun and Ssentongo53,Reference Chen, Haupert, Zimmermann, Shi, Fritsche and Mukherjee57 Another study reported that, regardless of the initial disease severity, COVID-19 survivors had longitudinal improvements in physical and mental health, with most returning to their original work within 2 years. Reference Huang, Li and Gu52 However, survivors had a remarkably lower health status than the general population at 2 years. Reference Huang, Li and Gu52 The CDC reports that individuals with post-COVID conditions may experience many symptoms that can last more than 4 weeks or even months after infection and the symptoms may initially resolve but subsequently recur. 7 This differs from the WHO definition where post-COVID conditions are defined to occur in individuals who have a history of probable or confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection; usually within 3 months from the onset of COVID-19, with symptoms and effects that last for at least 2 months. 58 A clearer and more standardized definition of post-COVID conditions is needed for researchers to investigate the true prevalence among those who are vaccinated and unvaccinated, and to evaluate the VE against post-COVID conditions.

While our previous meta-analysis on the same topic, but with a single vaccine dose instead of two doses, suggested that COVID-19 vaccines might effectively prevent post-COVID conditions even if administered after a COVID-19 infection, Reference Marra, Kobayashi and Suzuki9 the present meta-analysis did not demonstrate any protective effect when vaccines were given after COVID-19 infection. There are a few potential reasons for this discrepancy. Our previous meta-analysis Reference Marra, Kobayashi and Suzuki9 included three papers, including two preprint papers. However, none of these three papers met the inclusion criteria for the present study (two preprint papers and one paper focusing on a single vaccine). Instead, the present study included five new papers, one of which reported protection while the other four did not. It is important to interpret this stratified analysis cautiously, as one of the four studies without protection had a considerably larger sample size of over 390,000 individuals, accounting for more than 98% of the total sample size in the stratified analysis. Reference Meza-Torres, Delanerolle and Okusi40 Further studies will be necessary to investigate the effect of COVID-19 vaccines against post-COVID conditions when administered after a COVID-19 infection.

Our study had several limitations. First, the majority of the included studies in the meta-analysis investigating the VE in preventing post-COVID conditions employ different observational study designs, including cohort studies, and case-control studies. Reference Emecen, Keskin and Turunc14,Reference Kahlert, Strahm and Güsewell17,Reference Ayoubkhani, Bosworth and King29–Reference Ballouz, Menges and Kaufmann31,Reference El Otmani, Nabili, Berrada, Bellakhdar, El Moutawakil and Abdoh Rafai33,Reference Hajjaji, Lepoutre and Lakhdar34,Reference Ioannou, Baraff and Fox36–Reference Nehme, Braillard and Chappuis42,Reference Pinato, Ferrante and Aguilar-Company44,Reference Richard, Pollett and Fries45,Reference Senjam, Balhara and Kumar47–Reference Zisis, Durieux, Mouchati, Perez and McComsey51,Reference Perlis, Santillana and Ognyanova54 Second, features such as age, underlying health conditions, immunosuppression status, and prior COVID infection history can influence both VE and the likelihood of developing post-COVID conditions. Controlling these confounding features can be challenging in observational studies, and residual confounding factors may impact the accuracy of the estimates. Third, studies on VE for post-COVID conditions may focus on specific populations (e.g., hospitalized individuals), or geographical areas, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other settings or populations. Fourth, VE against post-COVID conditions may change over time due to the emergence of new variants, waning immunity, or the need for additional booster doses. Understanding the dynamics of VE and the potential impact of these time-dependent effects is an ongoing area of research. Fifth, we could not find any studies that evaluated the impact of a second booster dose or bivalent vaccines on VE against post-COVID conditions. Additionally, since the definition of post-COVID conditions varies significantly over the included studies, overdiagnosis and misdiagnosis could be present. Lastly, the abstract screening was performed by one reviewer (ARM), while the review of articles was conducted independently by two individuals.

In conclusion, receiving two doses of the COVID-19 vaccine prior to COVID-19 infection significantly reduces the risk of developing post-COVID conditions compared to those who are unvaccinated during the study period, including the Omicron variant era. Vaccine effectiveness against post-COVID conditions was higher when a third dose was administered. However, no protection against post-COVID conditions was observed with vaccinations given after a person had already contracted COVID-19. More observational studies are needed to evaluate bivalent COVID-19 vaccines, vaccination after COVID-19 infection, VE of a second booster dose, VE of mixing COVID-19 vaccines, and genomic surveillance for better understanding of VE against post-COVID conditions. A more standardized definition of post-COVID conditions is still needed both for research and clinical purposes.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/ash.2023.447

Acknowledgments

We thank Jennifer Deberg, MLS, from the Hardin Library for the Health Sciences, University of Iowa Libraries, for assistance with the search methods.

Financial support

This study was not funded.

Competing interests

All authors report no conflict of interest relevant to this article.