Introduction

With the expansion of the human impact on natural areas across the globe, the designation of protected areas, reserves and national parks that are sufficient in size, number and diversity to serve as representative examples of natural ecosystems and reservoirs of biodiversity becomes increasingly important. Polar regions are not exempt and, despite Antarctica‘s relative isolation and the common perception of the continent as a wilderness area, the effective use of conservation tools made available through international agreement is important for the current and future management and protection of the continent’s biodiversity and ecosystem values. Since the entry into force of the Antarctic Treaty in 1961, its signatory nations (known as Parties) have paid particular attention to the protection of the Antarctic environment. Their commitment to this end was strengthened with the adoption of the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty (agreed in 1991, entered into force in 1998), hereafter termed ‘the Protocol’. The Protocol provides for the comprehensive protection of the Antarctic environment and designates Antarctica as a ‘natural reserve, devoted to peace and science’. Annex II to the Protocol concerns the ‘Conservation of Antarctic Fauna and Flora’ and prohibits harmful interference by Parties to ensure that ‘the diversity of species, as well as the habitats essential to their existence, and the balance of the ecological systems existing within the Antarctic Treaty area are maintained’.

Annex V to the Protocol (which entered into force in 2002) is the current mechanism providing for the designation of Antarctic Specially Protected Areas (ASPAs), the purpose of which is to protect areas with outstanding environmental, scientific, historical, wilderness or aesthetic values or planned or ongoing scientific research (Article 3.1 of Annex V) within a systematic environmental-geographical framework. The term ‘values’ is particularly important as, in order to propose the designation of such an area, a formal description of the values contained within its boundaries must be given. The values listed in Annex V are:

a) areas kept inviolate from human interference so that future comparisons may be possible with localities that have been affected by human activities;

b) representative examples of major terrestrial, including glacial and aquatic, ecosystems and marine ecosystems;

c) areas with important or unusual assemblages of species, including major colonies of breeding native birds or mammals;

d) the type locality or only known habitat of any species;

e) areas of particular interest to ongoing or planned scientific research;

f) examples of outstanding geological, glaciological or geomorphological features;

g) areas of outstanding aesthetic and wilderness value;

h) sites or monuments of recognised historic value; and

i) such other areas as may be appropriate to protect the values identified in Article 3.1 (as detailed above).

The importance of environmental protection in the Antarctic was reaffirmed in 2021 through the Paris Declaration on the occasion of the 60th anniversary of the Antarctic Treaty entering into force and the 30th anniversary of the signing of the Protocol (ATCM 2021). Through the Declaration, Parties reaffirmed their commitment to ‘take account of best available scientific and technical advice in … the designation and preparation of management plans for Antarctic Specially Protected Areas and Antarctic Specially Managed Areas’ (ATCM 2021). The Committee for Environmental Protection (CEP) is the international body that oversees the ASPA process and advises the Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting (ATCM; CEP 2000).

The Protocol and its annexes appear to provide robust mechanisms for the conservation of Antarctic values. However, concerns have been raised in recent years over the effectiveness of the implementation of the Protocol and of the current protected area system (Shaw et al. Reference Shaw, Terauds, Riddle, Possingham and Chown2014, Hughes et al. Reference Hughes, Ireland, Convey and Fleming2016, Coetzee et al. Reference Coetzee, Convey and Chown2017, Wauchope et al. Reference Wauchope, Shaw and Terauds2019). Issues raised include that of spatial bias in the designation of ASPAs towards proximity to national research stations and to a subset of research interests (Coetzee et al. Reference Coetzee, Convey and Chown2017, Hughes & Grant Reference Hughes and Grant2017, Wauchope et al. Reference Wauchope, Shaw and Terauds2019). Wauchope et al. (Reference Wauchope, Shaw and Terauds2019) specifically warned against bias towards easily detectable and charismatic species and suggested that ‘[s]ystematic processes to prioritize area protection using the best available data will maximize the likelihood of ensuring long-term protection and conservation of Antarctic biodiversity’. More recently, Hawes et al. (Reference Hawes, Howard-Williams, Gilbert and Joy2021) and Howard-Williams et al. (Reference Howard-Williams, Hawes and Gilbert2021) argued that inland waters in Antarctica were particularly underrepresented in the ASPA system, especially considering their important contribution to biodiversity in what is primarily a desert continent.

The aim of this paper is therefore to advance the case for the explicit inclusion of inland waters as elements of special value within the protected area system for Antarctica. To this end, we review existing information that shows how inland waters are focal points of endemic biodiversity, uniqueness and productivity disproportionate to their area (Laybourn-Parry & Wadham Reference Laybourn-Parry and Wadham2014, Convey Reference Convey2017). We highlight the diversity and biodiversity of inland waters and their high levels of endemism at both continental and regional scales. We review the extent to which existing ASPAs provide protection for this vulnerable and irreplaceable resource and develop a systematic approach to target the protection of catchments that contain a diversity of representative aquatic (and other) habitats and biota.

The significance of Antarctic inland water bodies

The geographical range and diversity of inland aquatic ecosystems

Inland aquatic ecosystems such as streams, ponds and lakes occur on ice-free land as well as on ice surfaces across Antarctica (Laybourn-Parry & Wadham Reference Laybourn-Parry and Wadham2014). They have been recorded as far south as ice-free ground occurs, including in the Pensacola Mountains at 83–84°S (Hodgson et al. Reference Hodgson, Convey, Verleyen, Vyverman, McInnes and Sands2010) and inland nunataks of the Transantarctic Mountains at 86.5°S (Broady & Weinstein Reference Broady and Weinstein1998). Ice-free regions, however, represent < 0.4% of Antarctica, and they occur as isolated areas at widely spaced intervals around the continent, predominantly in coastal regions (Terauds et al. Reference Terauds, Chown, Morgan, Peat, Watts and Keys2012, Burton-Johnson et al. Reference Burton-Johnson, Black, Fretwell and Kaluza-Gilbert2016), potentially limiting the connectivity of inland waters across the continent. However, at latitudes and altitudes where glacial ice and snow melt can occur in summer, cryoconite holes, supraglacial streams, ponds and lakes are often abundant on the ice surfaces (Vincent & Laybourn-Parry Reference Vincent and Laybourn-Parry2008, Laybourn-Parry & Wadham Reference Laybourn-Parry and Wadham2014, Howard-Williams et al. Reference Howard-Williams, Hawes, Doran, Siegert, Carmacho and Kaup2019, Hawes et al. Reference Hawes, Howard-Williams, Gilbert and Joy2021). The presence of liquid water within the snow matrix on glacial ice also supports freshwater organisms as snow communities. Snow- and ice-based habitats support a range of microbial groups and even micro-invertebrates, and they contribute considerably to ‘terrestrial’ primary productivity in those parts of Antarctica where such summer melt occurs (Davey et al. Reference Davey, Norman, Sterk, Huete-Ortega, Bunbury and Loh2019, Gray et al. Reference Gray, Fretwell, Smith, Gray, Fretwell and Smith2020, Reference Gray, Krolikowski, Fretwell, Convey, Lloyd and Peck2021). These are fully functioning and diverse ecosystems, containing both elements specific to the ice-based habitat and others in common with neighbouring ice-free ground and water bodies (Hawes et al. Reference Hawes, Howard-Williams, Fountain, Vincent and Laybourn-Parry2008, Convey et al. Reference Convey, Biersma, Casanova-Katny, Maturana, Oliva and Ruiz-Fernández2020). They may also provide some connectivity between ice-free areas.

The largest inland aquatic ecosystems in Continental Antarctica are subglacial lakes, the largest of which is Lake Vostok, at ~250 km long and 50 km wide with an average depth of 450 m. The lake is overlain by a 4 km depth of ice. The temperature of the base of the Antarctic ice sheet is close to the melting point, and subglacial lakes are now known to be widespread, numbering at least 400 (Siegert et al. Reference Siegert, Kulessa, Bougamont, Christoffersen, Key, Andersen, Siegert, Jamieson and White2018), with indications that many are linked by subglacial water flows (Mackie et al. Reference Mackie, Schroeder, Caers, Siegfried and Scheidt2020). However, techniques to sample such habitats safely in a bio-secure manner are only now being developed (Siegert & Kennicutt Reference Siegert and Kennicutt2018, Makinson et al. Reference Makinson, Anker, Garces, Goodger, Polfrey and Rix2021). Consideration of their protection through the designation of ASPAs will be applicable to subglacial lakes in future as research and understanding of these systems advance, but we do not deal with them further here.

Surface inland aquatic water bodies in Antarctica can broadly be divided into three partly overlapping zones based on regional variability in dominant processes controlling climate, hydrology, recent history and basin origins (Laybourn-Parry & Wadham Reference Laybourn-Parry and Wadham2014). These zones are:

• The Maritime Antarctic, comprising the relatively mild western coast of the Antarctic Peninsula and its offshore islands and the more distant archipelagos of the South Shetland and South Orkney islands;

• The coastal oases of Continental Antarctica, at 0–120°E and at 65–70°S;

• The polar deserts of Continental Antarctica, including inland mountain ranges and nunataks, the best known of which (and largest of the ice-free areas) is the McMurdo Dry Valleys region, Victoria Land, centred on 162°E, 77.5°S.

The Maritime Antarctic is the wettest part of Antarctica, where low positive mean monthly air temperatures are typically experienced for 1–4 months in summer (Convey Reference Convey2017). Precipitation can be as rain in summer and has been increasingly so in recent years as regional temperatures have increased associated with climate change (Convey & Peck Reference Convey and Peck2019). This, together with the melting of thick winter snow accumulations and increasingly deep permafrost active layer thawing, can result in streams that flow for up to 4 months over summer, support extensive seasonal algal growth and feed many ponds and lakes (Hawes Reference Hawes, Kerry and Hempel1990, Toro et al. Reference Toro, Camacho, Rochera, Rico, Bañón and Fernández-Valiente2007, Lyons et al. Reference Lyons, Welch, Welch, Camacho, Rochera and Michaud2013). In this region, networks of streams, wetlands and seepages are frequent.

While these waters are often oligotrophic, in some coastal areas marine vertebrates coming onshore may cause nutrient enrichment (eutrophication; Hawes Reference Hawes, Kerry and Hempel1990, Pizarro Reference Pizarro, Vinocur and Tell2002, Quayle et al. Reference Quayle, Peck, Peat, Ellis-Evans and Harrigan2002, Bokhorst et al. Reference Bokhorst, Convey and Aerts2019). Lakes and ponds are usually at least partially ice -free in summer (Toro et al. Reference Toro, Camacho, Rochera, Rico, Bañón and Fernández-Valiente2007) for a variable period of time (Rochera & Camacho Reference Rochera and Camacho2019). Plentiful meltwater means that most are exorheic (with inflows and outflows), well flushed with fresh water and maintain stable water levels. The catchments contributing to maritime lakes may be partially vegetated with microbial mats, mosses, liverworts and, in places, vascular plants that provide some organic and inorganic nutrient inputs to the water bodies (Toro et al. Reference Toro, Camacho, Rochera, Rico, Bañón and Fernández-Valiente2007).

Sediment records show that most lakes in the Maritime Antarctic occupy basins that emerged after the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), suggesting that this part of Antarctica, particularly low-lying areas where lakes currently exist, was largely covered by ice during the LGM (Hall Reference Hall2009). However, the presence of multiple endemic terrestrial organisms within the Maritime Antarctic (Convey et al. Reference Convey, Stevens, Hodgson, Smellie, Hillenbrand and Barnes2009, Reference Convey, Biersma, Casanova-Katny, Maturana, Oliva and Ruiz-Fernández2020, Biersma et al. Reference Biersma, Jackson, Stech, Griffiths, Linse and Convey2018) suggests that ice-free refugia were probably present through glaciations. Molecular studies also indicate both post- and pre-LGM presence of the freshwater copepod Boeckella poppei (Maturana et al. Reference Maturana, Segoia, González-Wevar, Rosenfield, Pouli, Jackson and Convey2020, Reference Maturana, Rosenfeld, Biersma, Segovia, González-Wevar and Díaz2021). Furthermore, sediment cores from freshwater Clincher Lake on Horseshoe Island in the southern Maritime Antarctic (some of the longest obtained from this region) indicate a lake basin that predates the last glaciation, with two lacustrine facies (from post-10,000 and pre-20,000 years ago) separated by a period of glacial override (Hodgson et al. Reference Hodgson, Roberts, Smith, Verleyen, Sterken and Labarque2013). Some degree of long-term persistence of aquatic habitat and organisms in the Maritime Antarctic, at least through the LGM, seems probable.

Coastal oases are found on the continental margins in relatively recent landscapes often formed as a result of isostatic uplift of the land surface following the Holocene retreat of the ice sheet at the end of the LGM (e.g. Hodgson et al. Reference Hodgson, Whitehouse, De Cort, Berg, Verleyen and Tavernier2016). As with the Maritime Antarctic, diverse lines of evidence suggest the persistence of aquatic organisms in these oases through the LGM and possibly longer, and it has been proposed that lacustrine refugia existed through these events (Hodgson et al. Reference Hodgson, Verleyen, Sabbe, Squier, Keely and Leng2005, Gibson et al. Reference Gibson, Paterson, White and Swadling2009, Pinseel et al. Reference Pinseel, Van de Vijver, Wolfe, Harper, Antoniades and Ashworth2021). Summer melt streams here are mostly small and short (Mergelov Reference Mergelov2014), the larger ones mostly originating from the East Antarctic Ice Sheet or local glaciers. Significant flows have been recorded in streams draining the ice sheet (e.g. up to 6 m3 s-1 in Algae River, Bunger Hills; Gibson et al. Reference Gibson, Gore and Kaup2002). Ponds and small lakes are primarily ice free in summer, and larger lakes demonstrate a mix of summer ice-free and ice-capped conditions. At the Vestfold Hills, most are freshwater, but brackish to hypersaline systems resulting from evaporative concentration and/or the evolution of trapped sea water are also reported (Burton Reference Burton and Williams1981). Lakes with significant salt contents are often chemically stratified (meromictic) where meltwater has overridden relic sea water (Ferris & Burton Reference Ferris and Burton1988, Kumar et al. Reference Kumar, Shokri and Mehrotra2002, Gibson Reference Gibson2004, Cromer et al. Reference Cromer, Gibson, Swadling and Hodgson2006, Kudoh & Tanabe Reference Kudoh and Tanabe2014). Tidal epishelf lakes (Fig. 1) are found along the marine margins of some coastal oases (Laybourn-Parry & Wadham Reference Laybourn-Parry and Wadham2014) where ice shelves butt up to the shoreline, and they are also found in two locations on Alexander Island (Ablation Massif; Fig. 1c) close to the southern boundary of the Maritime Antarctic (Heywood Reference Heywood1977). Epishelf lakes are characterized by a layer of fresh water that overlays sea water that connects to the ocean under the ice shelf, and they show tidal cycles (Doran et al. Reference Doran, Wharton, Lyons and Des Marais2000).

Fig. 1. Examples of Antarctic inland water ecosystems. a. Summer ice-free lakes on Signy Island, South Orkney Islands, Maritime Antarctic. b. The catchment of the perennially ice-covered Trough Lake (extreme right, McMurdo Dry Valleys) contains a number of streams and ponds with perennial or seasonal ice cover. c. Ablation Lake on Alexander Island - a proglacial epishelf lake. d. The Vestfold Hills - a coastal oasis - contain a large number of lakes of varying salinity, including meromictic lakes. e. Byers Peninsula, Maritime Antarctica, supports a diverse array of streams, ponds and lakes that are recognized for protection within the Antarctic Specially Protected Area framework. f. Continental Antarctica has many isolated water bodies with varying extents of summer ice cover, most with well-developed, orange cyanobacterial mats. g. At 27 km, the Onyx is Antarctica‘s longest river. It has a > 50 year flow record. h. & i. Typical shallow streams in Continental and Maritime Antarctica, respectively. j. Freshwater lakes on the edge of the ice cap at Schirmacher coastal oasis. Lake Globukoye is in the foreground. k. Small ’kettle hole' ponds are conspicuous life-supporting habitats on moraines in Continental Antarctica, such as here on the margins of Koettlitz Glacier. l. Lake Fryxell in the McMurdo Dry Valleys in late January when the lake margin is at its most melted. All images are from the authors except g. (Australian Antarctic Division) and j. (D. Andersen).

Polar deserts, including inland nunataks, are characterized by very low precipitation and barren, often ancient landscapes (with surfaces exposed sometimes for >106 years). Sources of freshwater are predominantly solar-driven glacial melt in summer and melt-stream discharges are characterized by variability at diurnal, intra-summer and inter-annual timescales (Howard-Williams et al. Reference Howard-Williams, Vincent, Broady and Vincent1986, McKnight et al. Reference McKnight, Nyogi, Alger, Bomblies, Conovitz and Tate1999). Some polar desert melt streams may be large, such as the Onyx River which is over 25 km long and collects meltwater from a series of lowland glaciers and often flows at >1 m3 s-1 (Chinn and Mason Reference Chinn and Mason2016). These desert landscapes are frequently characterised by endorheic catchments and saline and brackish lakes and ponds are common through evaporative- and freeze- concentration of salts (Wharton Reference Wharton1991). Recent studies have also indicated extensive saline groundwater beneath much of Taylor Valley (Mikucki et al. Reference Mikucki, Auken, Tulaczyk, Virginia, Schamper and Sørensen2015, Foley et al. Reference Foley, Tulaczyk, Grombacher, Doran, Mikucki and Myers2019) and parts of the Wright Valley (Toner et al. Reference Toner, Catling and Sletten2017).

Polar desert ponds typically remain ice capped in summer, with only a few smaller examples gaining sufficient heat to become ice free, and most are salinity stratified (Healy et al. Reference Healy, Webster-Brown, Brown and Lane2006, Lyons et al. Reference Lyons, Welch, Gardner, Jaros, Moorhead, Knoepfle and Doran2012, Hawes et al. Reference Hawes, Howard-Williams, Gilbert and Joy2021). Lakes such as those of the McMurdo Dry Valleys (Priscu Reference Priscu1998, Hawes et al. Reference Hawes, Howard-Williams, Gilbert and Joy2021) are typically characterized by thick perennial ice caps. A few are completely frozen with perhaps a liquid basal brine layer such as that found in Lake Vida and Lake House (Dugan et al. Reference Dugan, Doran, Wagner, Kenig, Fritsen and Arcone2015). Many polar desert lakes are chemically stratified with increasing salt concentrations towards the base (meromictic) due to historical alternations between periods of inflow exceeding ablation and vice versa (Stein et al. 2000). For instance, Lake Vanda (7.5 km2, 78 m deep) has multiple brine layers and year-round bottom temperatures of > 20°C (Priscu Reference Priscu1998), and, like most dry valley lakes, it also supports a narrow ‘moat’ around the margin that becomes ice free during summer (Ramoneda et al. Reference Ramoneda, Hawes, Pascual-Garcia, Mackey, Sumner and Jungblut2021).

The McMurdo Dry Valleys were probably not ice filled during the LGM and earlier Pleistocene glaciations (Hall Reference Hall2009), and there is evidence from cosmogenic dating of rocks of the Transantarctic Mountains that nunataks were also not completely overridden by ice at that time (Hillebrand et al. Reference Hillebrand, Stone, Koutnik, King, Conway and Hall2021). The persistence of inland water bodies in the polar deserts throughout (at least) Pleistocene glaciations is implicit in the studies of Verleyen et al. (Reference Verleyen, Van de Vijver, Tytgat, Pinseel, Hodgson and Kopalová2021) and Pinseel et al. (Reference Pinseel, Van de Vijver, Wolfe, Harper, Antoniades and Ashworth2021), who analysed the biogeography of diatom floras, and of Hodgson et al. (Reference Hodgson, Bentley, Schnabel, Cziferszky, Fretwell, Convey and Xu2012), who used stable isotopes to show exposure ages of > 106 years in the Dufek Massif. Following the LGM, glacial melting resulted in large lakes being formed in some of the McMurdo Dry Valleys, which subsequently drained, evaporated and refilled as climate cycled through warm and cold episodes (Hall Reference Hall2009). Long persistence but frequent change appears to be a feature of polar desert water bodies.

Biodiversity and endemism in inland waters

The availability of liquid water is the single most important physical driver of Antarctic terrestrial biodiversity, particularly at higher continental latitudes (Convey et al. Reference Convey, Chown, Clarke, Barnes, Bokhorst and Cummings2014). For this reason, inland aquatic habitats, even where they are frozen for much of the year, have been recognized since the earliest expeditions of Scott and Shackleton as centres for biodiversity and biological productivity (Murray Reference Murray1910, Fritsch Reference Fritsch and Bell1912). Antarctic inland water bodies do, however, show impoverished biodiversity for most biological groups, even compared to other cold regions, reflecting both the extreme climate, particularly during past glacial maxima, and the challenges to potential colonists crossing the expanse of the Southern Ocean and locating suitable habitats (Laybourn-Parry & Wadham Reference Laybourn-Parry and Wadham2014). All Antarctic inland waters, for example, lack vertebrates and have depauperate macroinvertebrate communities (Dartnall Reference Dartnall2017). Molluscs are absent, aquatic insects are rare, the only obligate aquatic example being the chironomid midge (Parochlus steinenii), which is confined in its current Antarctic distribution to the South Shetland Islands to the north of the Antarctic Peninsula (Chown & Convey Reference Chown and Convey2016, Rochera and Camacho Reference Rochera and Camacho2019, Contador et al. Reference Contador, Gañan, Bizama, Fuentes-Jaque, Morales and Rendoll2020), while the larvae of the endemic flightless midge Belgica antarctica occur on the margins of aquatic habitat, where they are tolerant of long exposures to inundation. A species-poor assemblage of planktonic and epibenthic crustaceans is present, with distinct and often discreet distributions around various parts of the continent (Dartnall Reference Dartnall2017, Maturana et al. Reference Maturana, Rosenfeld, Biersma, Segovia, González-Wevar and Díaz2021).

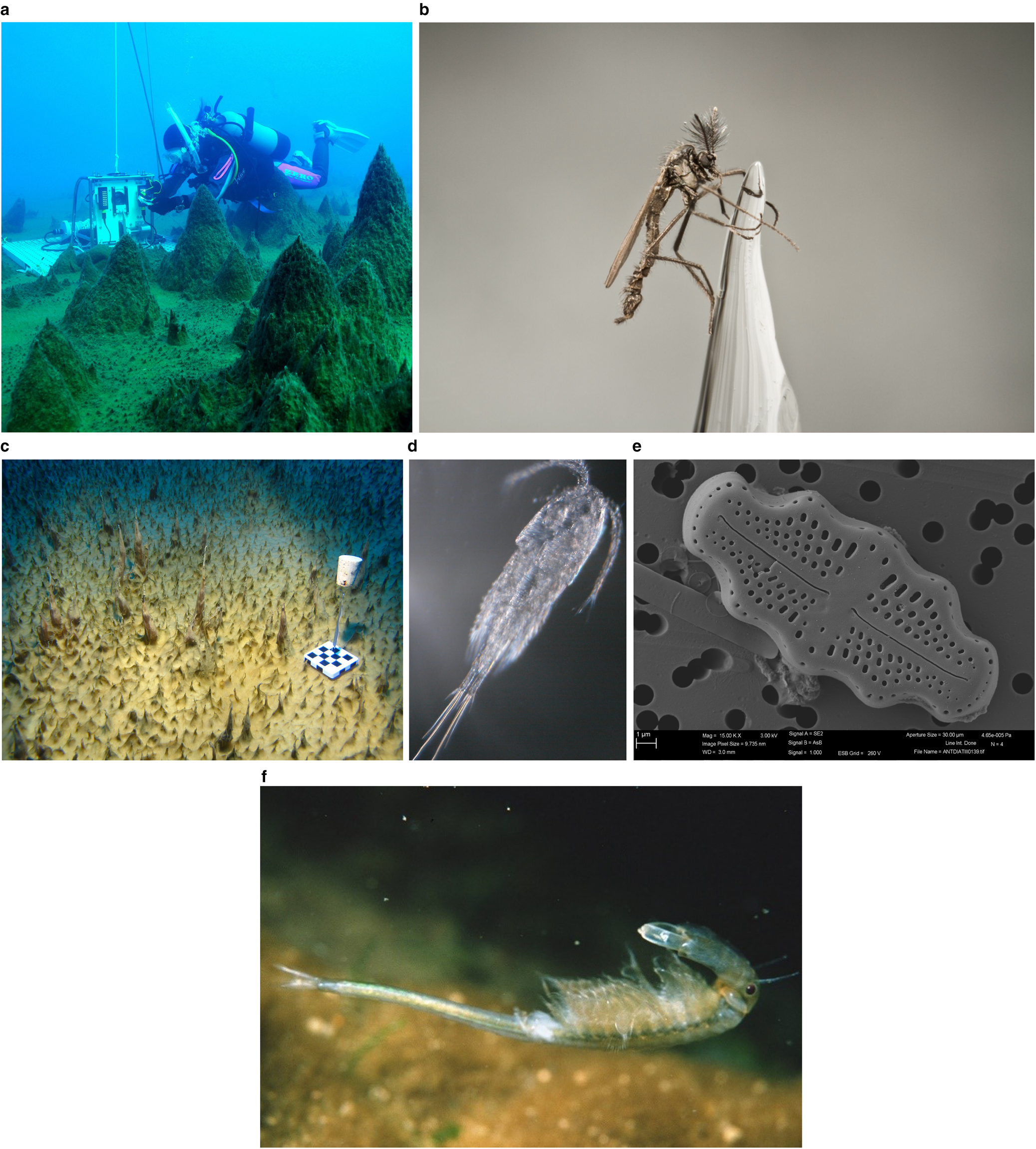

Antarctic inland waters are overwhelmingly dominated by microbes. Filamentous, mat-forming cyanobacteria are responsible for most of the benthic biomass and primary production (Jungblut et al. Reference Jungblut, Vincent and Lovejoy2012, Pessi et al. Reference Pessi, Lara, Durieu, Maalouf, Verleyen and Wilmotte2018), though in some locations mosses (Li et al. Reference Li, Ochyra, Wu, Seppelt, Cai, Wang and Li2009) and diatoms (Vyverman et al. Reference Hodgson, Convey, Verleyen, Vyverman, McInnes and Sands2010) are important (Fig. 2a,c,e). Micro-invertebrates are common in both the lake floor and water column communities (Fig. 2b,d,f), particularly protozoa (ciliates and amoeba), rotifers, nematodes, tardigrades, oligochaetes and flatworms (e.g. Murray Reference Murray1910, Maslen & Convey Reference Maslen and Convey2006, Adams et al. Reference Adams, Wall, Virginia, Bross and Knox2014, Obbels et al. Reference Obbels, Verleyen, Mano, Namsaraev, Sweetlove and Tytgat2014, Velasco-Castrillon et al. Reference Velasco-Castrillón, Gibson and Stevens2014, Iakovenko et al. Reference Iakovenko, Smykla, Convey, Kašparová, Kozeretska and Trokhymets2015).

Fig. 2. Examples of Antarctic inland water biota. a. Moss pillars in a freshwater lake in Syowa Oasis (image: D. Andersen). b. Parochlus steinenii, Antarctica's only obligate aquatic insect (image: G. Arriagoda). c. Microbial mat at 20 m depth in Lake Vanda forming tall cuspate pinnacles (image: T. Mackey). d. Diacyclops joycei, a cyclopoid copepod endemic to Antarctica and currently known only from Lake Joyce (image: I. Hawes). e. Scanning electron micrograph of a diatom (Luticola contii) from Maritime Antarctic lakes (image: B. Van de Vijver). f. Branchinecta gainii, a univoltine anostracan from the Maritime Antarctic (image: British Antarctic Survey).

Recent taxonomic investigations using molecular approaches have revealed a previously unexpected high level of continental and regional endemism in the Antarctic freshwater biota and the probable persistence of organisms in refugia through past glaciations (Convey & Stevens Reference Convey and Stevens2007, Gibson & Bayly Reference Gibson and Bayly2007, Karanovic et al. Reference Karanovic, Gibson, Hawes, Andersen and Stevens2014, Convey et al. Reference Convey, Biersma, Casanova-Katny, Maturana, Oliva and Ruiz-Fernández2020, Pinseel et al. Reference Pinseel, Van de Vijver, Wolfe, Harper, Antoniades and Ashworth2021). Diatoms, for example, have been found to be characterized by high levels of endemism and provincialism, consistent with persistence through repeated glaciations rather than recent colonization (Verleyen et al. Reference Verleyen, Van de Vijver, Tytgat, Pinseel, Hodgson and Kopalová2021). At the highest level of lake-obligate organisms found in Antarctica - the crustaceans - there is evidence from lake sediment cores of their continued persistence through multiple glacial cycles, necessitating the presence of continental freshwater refugia (Gibson & Bayly Reference Gibson and Bayly2007, Karanovic et al. Reference Karanovic, Gibson, Hawes, Andersen and Stevens2014). Conversely, sediment analyses also show how taxa may be lost during glacial expansion cycles (Pinseel et al. Reference Pinseel, Van de Vijver, Wolfe, Harper, Antoniades and Ashworth2021). The potential importance of epishelf lakes in providing refugia through glacial periods has also been proposed (Gibson & Bayly Reference Gibson and Bayly2007, Hodgson et al. Reference Hodgson, Roberts, Smith, Verleyen, Sterken and Labarque2013, Davies et al. Reference Davies, Hambrey, Glasser, Holt, Rodés and Smellie2017), and proglacial and epiglacial lakes currently support a benthic and planktonic biota from bacteria to micro-invertebrates (e.g. Webster-Brown et al. Reference Webster-Brown, Gall, Gibson, Wood and Hawes2010; authors’ unpublished observations) and may also have provided refugia.

Biogeography of inland waters

Developing a representative portfolio of protected areas requires an understanding of the biogeography of Antarctic inland waters. This is challenged by incomplete coverage, in terms of geography and taxonomy. As is the case across Antarctic terrestrial ecosystems, relatively few areas have been investigated in detail, with most that have been investigated being close to existing research facilities. The available studies often address only a small subset of the inland water biota, while morphology-based taxonomy is often unreliable (Hawes et al. Reference Hawes, Jungblut, Elster, Van de Vijver and Mikucki2019). Two examples serve to illustrate this: crustaceans and micro-invertebrates.

Dartnall (Reference Dartnall2017) summarizes the multiple misidentifications in the literature of the only freshwater calanoid copepod in Antarctica, B. poppei. Maturana et al. (Reference Maturana, Rosenfeld, Biersma, Segovia, González-Wevar and Díaz2021), in the first molecular phylogeographic study of this genus, have recently confirmed that all Maritime and Continental Antarctic material available can be assigned to this single species. Dartnall (Reference Dartnall2017) goes on to describe equal confusion in the identity and distribution of a group of cyclopoid copepod species now placed within the genus Diacyclops. A recent revision of the Antarctic members of the genus concludes that there are four species, with largely disjunct distributions in widely separated sites across Continental Antarctica. One (Diacyclops joycei) is known from a single lake in the McMurdo Dry Valleys, another (Diacyclops walker) from the Vestfold Hills, and both Diacyclops mirnyi and Diacyclops kaupi occur in the Bunger Hills (Karanovic et al. Reference Karanovic, Gibson, Hawes, Andersen and Stevens2014). Dartnall's (Reference Dartnall2017) review also indicates that, while all other oases contain one or more of these copepods, none have yet been reported from the Schirmacher Oasis, although this apparent gap may simply reflect the absence of sampling.

Iakovenko et al. (Reference Iakovenko, Smykla, Convey, Kašparová, Kozeretska and Trokhymets2015) and Cakil et al. (Reference Cakil, Garlasché, Iakovenko, Di Cesare, Eckert and Guidetti2021) have examined Antarctic bdelloid rotifers, a group that is abundant within a variety of inland waters. Their studies emphasize how a fauna that was historically assumed to be largely cosmopolitan is now recognized as highly endemic, and they also stressed that ‘the concept of endemism is itself limited by the quality and extent of the data available’. To this must be added the challenge of defining ‘species’ across spatially segregated populations within which drift and founder effects may exacerbate divergence within species. Molecular data allowed these authors to recognize 12 species new to science, including at least four cryptic species that appear to be morphologically identical to other taxa. They conclude that full recognition of the diversity, affinities and biogeography of organisms across Antarctica requires the extensive and thorough application of molecular techniques across a wide range of taxonomic groups, a widely supported perspective across marine and terrestrial biota in Antarctica (Gutt et al. Reference Gutt, Isla, Xavier, Adams, In-Young Ahn and Cheng2021).

The Gressitt Line (Chown & Convey Reference Chown and Convey2007) represents one of the clearest evidence-based biogeographical boundaries in Continental Antarctica, separating the Antarctic Peninsula and its offshore islands from the remainder of the continent. For the Acari, Collembola and Nematoda (the major groups of Antarctic terrestrial fauna for which sufficient data exist), it is apparent that few if any currently recognized species are shared across this line, and as molecular analyses are extended to other groups such as Tardigrada this pattern is again becoming apparent (Guidetti et al. Reference Guidetti, Massa, Bertolani, Rebecchi and Cesari2019, Short Reference Short2020, Short et al. Reference Short, Sands, McInnes, Pisani, Stevens and Convey2022). This deep biogeographical division at the Gressitt Line applies to aquatic diatoms (Verleyen et al. Reference Verleyen, Van de Vijver, Tytgat, Pinseel, Hodgson and Kopalová2021) and many groups of freshwater metazoans (e.g. Gibson et al. Reference Gibson, Wilmotte, Taton, Van de Vijver, Beyens, Dartnal, Bergstrom, Convey and Huiskes2006, Dartnall Reference Dartnall2017). There are, for example, 12 mosses reported from permanently submerged aquatic habitats in Antarctica; eight are confined to the north of the Gressitt Line and three to the south, with only Bryum pseudotriquetrum occurring as an aquatic form in both regions (Li et al. Reference Li, Ochyra, Wu, Seppelt, Cai, Wang and Li2009). Similarly, micro-invertebrate faunas of sites on the continental side of the Gressitt Line are quite distinct from those on the peninsular side, with the latter having a more obvious affinity to South America than continental locations (Velasco-Castrillón et al. Reference Velasco-Castrillón, Gibson and Stevens2014).

Another biogeographical delineation - the Antarctic Conservation Biogeographic Regions (ACBRs) - identified 16 regions within Antarctica based on a combination of physical environmental layers and spatially explicit records of biodiversity included in the Antarctic terrestrial database (https://data.aad.gov.au/metadata/records/AAS_4296_Antarctic_terrestrial_biodiversity_DB; Terauds et al. Reference Terauds, Chown, Morgan, Peat, Watts and Keys2012, Terauds & Lee Reference Terauds and Lee2016). In practice, the available biodiversity records were predominantly of terrestrial bryophytes, lichens, mites and springtails (plus the two flowering plants and two insects that are confined to the Maritime Antarctic). There is no explicit reference to inland water bodies within the ACBRs. An earlier spatially limited attempt to validate a bioregionalization approach using aquatic cyanobacteria in lakes and ponds was not successful (Taton et al. Reference Taton, Grubisic, Balthazart, Hodgson, Laybourn-Parry and Wilmotte2006), and other evidence suggests that, as more information becomes available, many cold-tolerant cyanobacteria are increasingly seen to be shared broadly amongst cold regions (Chrismas et al. Reference Chrismas, Anesio and Sánchez-Baracaldo2015)

In addition to the existence of broad-scale patterns amongst at least some aquatic biota, at small scales it is clear that communities are closely linked to local environmental conditions. Habitat diversity is reflected in biological diversity. Within Antarctic lakes, distinct assemblages occupy discreet locations along environmental gradients (Jungblut et al. Reference Jungblut, Hawes, Mackey, Krusor, Doran and Sumner2016, Ramoneda et al. Reference Ramoneda, Hawes, Pascual-Garcia, Mackey, Sumner and Jungblut2021). In comparisons between water bodies, salinity appears to be a powerful driver of diversity (Archer et al. Reference Archer, McDonald, Herbold, Lee and Cary2015, Sutherland et al. Reference Sutherland, Howard-Williams, Ralph and Hawes2020, Jackson et al. Reference Jackson2021). In a recent classification exercise of small water bodies in the McMurdo Dry Valleys, significant differences in prokaryote and eukaryote biota in ponds with and without permanent ice cover were reported (Hawes et al. Reference Hawes, Howard-Williams, Gilbert and Joy2021). The duration of any ice-free period can dominate the physical structure of the water body, including thermal stratification, light penetration, turbulence and gas exchange. Ice cover also influences the input of new nutrients from melt in the watershed as well as the biogeochemical cycling of existing nutrients and has profound influence on system function (Kaup & Burgess Reference Kaup and Burgess2002, Rochera & Camacho Reference Rochera and Camacho2019).

Threats to inland water bodies

Human activities can result in significant impacts on Antarctic inland waters both directly, such as through activities from station operations, scientific activities, tourism, among others, and indirectly through anthropogenic climate change and long-distance atmospheric contamination (Kaup Reference Kaup2005, Bargagli Reference Bargagli2008, Tin et al. Reference Tin, Fleming, Hughes, Ainley, Convey and Moreno2009, Lynch et al. Reference Lynch, Fagan and Naveen2010, Aronson et al. Reference Aronson, Thatje and Hughes2011, Chown et al. Reference Chown, Huiskes, Gremmen, Lee, Terauds and Crosbie2012a). In addition, interactions between direct and indirect stressors are possible. For example, Convey & Peck (Reference Convey and Peck2019) considered that the establishment of non-native taxa from both within and beyond the continent may be the greatest threat to native biodiversity and that this will be facilitated by the amelioration of the climate and the increasing extent of human movement both to and within Antarctica (Frenot et al. Reference Frenot, Chown, Whinam, Selkirk, Convey, Skotnicki and Bergstrom2005, Chown et al. Reference Chown, Lee, Hughes, Barnes, Barrett and Bergstrom2012b, Hughes et al. Reference Hughes, Convey, Pertierra, Vega, Aragón and Olalla-Tárraga2019).

The presence of non-native species in inland water ecosystems has received little attention, with few examples having been documented (Hughes et al. Reference Hughes, Pertierra, Molina-Montenegro and Convey2015). One example is the collection of adults (including gravid females) of the non-native fly Trichocera maculipennis close to Lake Uruguay, near Artigas Station, and at a stream close to Bellingshausen Station, both located on Fildes Peninsula, King George Island (Remedios-De Leon et al. Reference Remedios-De León, Hughes, Morelli and Convey2021). The larvae of this fly are capable of developing in aquatic habitats, although they have not yet been observed on Fildes Peninsula. This context is consistent with observations in terrestrial systems of non-native taxa, most frequently in the rapidly changing and heavily visited Antarctic Peninsula region (Greenslade et al. Reference Greenslade, Potapov, Russel and Convey2012, Hughes et al. Reference Hughes, Pertierra, Molina-Montenegro and Convey2015, Reference Hughes, Pescott, Peyton, Adriaens, Cottier-Cook and Key2020). In contrast, attempts to identify the presence of exotic taxa in the more extreme continental inland waters by comparing recent and museum-preserved samples from the heroic era of exploration are yet to discover any such taxa (Jungblut & Hawes Reference Jungblut and Hawes2017, Velasco-Castrillón et al. Reference Velasco-Castrillón, Stevens and Hawes2018, Kohler et al. Reference Kohler, Howkins, Sokol, Kopalová, Cox and Darling2021).

In addition to the potential facilitation of colonization by new organisms, climate change is also directly affecting ecosystem function. In the Maritime Antarctic, air temperature warming trends have been amplified in lake systems, resulting in reduced duration of lake ice cover and associated increases in overall productivity (Quayle et al. Reference Quayle, Peck, Peat, Ellis-Evans and Harrigan2002, Reference Quayle, Convey, Peck, Ellis-Evans, Butler, Peat, Domack, Burnett, Leventer, Convey, Kirby and Bindschadler2003). Water-level rises in endorheic continental lakes in response to elevated inflow volumes have also impacted lake ecosystems, but these changes have not yet led to wholesale species turnover (Hawes et al. Reference Hawes, Sumner, Andersen, Jungblut and Mackey2013, Ramoneda et al. Reference Ramoneda, Hawes, Pascual-Garcia, Mackey, Sumner and Jungblut2021). As noted, the threat of synergistic effects between climate change and invasive species is, however, widely hypothesized for both Maritime and Continental Antarctica (Chown et al. Reference Chown, Lee, Hughes, Barnes, Barrett and Bergstrom2012b, Convey & Peck Reference Convey and Peck2019, Chown et al. Reference Chown, Leihy, Naish, Brooks, Convey and Henley2022), and the lack of non-native taxa recorded to date in the latter may simply reflect the currently minimal shift in habitat characteristics (Duffy & Lee Reference Duffy and Lee2019).

A number of Antarctic lakes have been negatively impacted by other forms of direct human activities at locations across the continent. Impacts can include contamination of lake catchment areas leading to increased nutrient and suspended matter inflow from nearby roads and research stations, changes to drainage patterns caused by, for example, road construction, pollution from rock dust, hydrocarbons, wastewater and station litter waste (Kaup Reference Kaup2005) and even as a result of scientific activities such as sampling and diving (Wharton & Doran Reference Wharton and Doran1998). Other threats are yet to be extensively evaluated, including plastic pollution, which has been described recently in glaciers that feed into lakes Uruguay and Ionosferico on King George Island (Gonzalez-Pleiter et al. Reference González-Pleiter, Edo, Velázquez, Casero-Chamorro, Leganés and Quesada2020) and has been reported as far south as the Ross Ice Shelf (Aves et al. Reference Aves, Revell, Gaw, Ruffell, Schuddeboom and Wotherspoon2022).

In 1986, an airdrop onto the ice of Lake Vanda resulted in a fuel spill (Harrowfield Reference Harrowfield1999) that received international attention. The spilt fuel was burnt off and the residual contaminated ice was scraped off as much as possible and returned to Scott Base. In January 2003, a US Bell 212 helicopter crashed onto the ice-covered surface of Lake Fryxell, Taylor Valley, McMurdo Dry Valleys (Alexander & Stockton Reference Alexander and Stockton2003). Seven hundred and thirty litres of aviation fuel and other lubricants were released onto the surface of the lake environment, of which no more than 45% was recovered by the emergency clean-up team. The remaining fuel may have evaporated or penetrated the ice cover to the water below and been subsequently transported to other previously uncontaminated sites, but, a year after the accident, a significant amount of fuel remained in the lake ice cover (Jarula et al. Reference Jarula, Kenig, Doran, Priscu and Welch2008). In a similar example, on 15 January 2010, a helicopter dropped three 200 l drums of diesel fuel onto soil adjacent to Lake Dingle in the Vestfold Hills (Australia State of the Environment 2012). Over the following two seasons, the Australian Antarctic Division removed 168 tonnes of contaminated topsoil to Davis Station for remediation, resulting in no detectable fuel in the lake water (Australia State of the Environment 2016).

Fildes Peninsula, King George Island, South Shetland Islands, is one of the most densely populated and impacted areas of Antarctica, with six research stations, a tourist camp, a port and an intercontinental airstrip and associated buildings (Peter et al. Reference Peter, Buesser, Mustafa and Pfeiffer2008, Braun et al. Reference Braun, Mustafa, Nordt, Pfeiffer and Peter2012, Convey Reference Convey2020, Remedios-De León et al. Reference Remedios-De León, Hughes, Morelli and Convey2021). It is one of the largest areas of ice-free ground in the region, and it contains 101 lakes and numerous smaller water bodies and streams. Many of the lakes have been subject to pollution with, for example, Long Lake, Laguna Hidrografos and others being contaminated by waste from former landfill sites (Tin & Roura Reference Tin and Roura2004). Other lakes close to research stations have been impacted, with Kitezk Lake, Laguna Las Estrellas and Biologensee Lake having considerable amounts of waste present on their shores (Peter et al. Reference Peter, Buesser, Mustafa and Pfeiffer2008). Hydrocarbon pollution has been noted in lakes Biologensee and Biologenbucht, lakes near the airstrip and in Laguna Tern, not far from the fuel tanks of Great Wall Station (Peter et al. Reference Peter, Buesser, Mustafa and Pfeiffer2008). Other impacts on lakes in Fildes Peninsula include the release of wastewater from the airport accommodation for tourists into a stream that feeds lakes Biologenbucht and Biologensee (Peter et al. Reference Peter, Buesser, Mustafa and Pfeiffer2008).

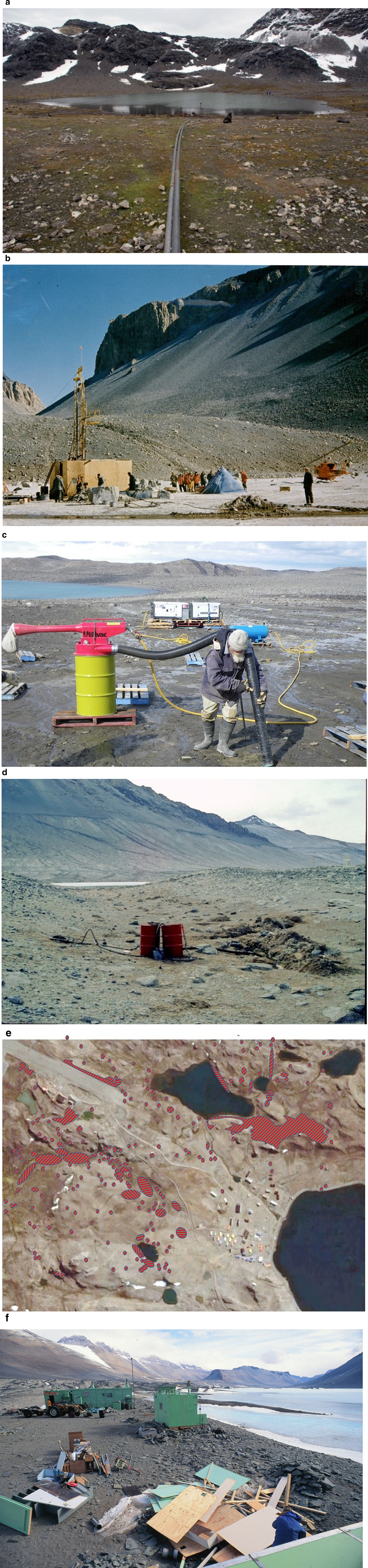

Impacts have also been documented in other Antarctic locations, including, for example, anthropogenic eutrophication in lakes Glubokoye and Stancionnoye in the Schirmacher Oasis (Kaup Reference Kaup2005) and in lakes in the Larsemann Hills (Ellis-Evans et al. Reference Ellis-Evans, Laybourn-Parry, Bayliss, Perris, Battaglia, Valencia and Walton1997, Kaup & Burgess Reference Kaup and Burgess2002). Low levels of trace metals, considered to have originated from local research stations, have been detected in freshwater lakes in the Larsemann Hills (Gasparon & Burgess Reference Gasparon and Burgess2000). Trace metals, nutrients, paint fragments and hydrocarbons have also been introduced to Lake Vanda in the McMurdo Dry Valleys through flooding of contaminated soils at the site of the now-removed research facility (Fig. 3; Sheppard et al. Reference Sheppard, Campbell and Claridge1993, Hawes et al. Reference Hawes, Smith and Sutherland1999, Webster et al. Reference Webster, Webster, Nelson and Waterhouse2003).

Fig. 3. Vanda Station in the 1970s (left), during its removal in 1993 (centre) and in 2015 (right). The location of the station huts in the 2015 image is indicated by the arrow. The station site and residual contaminants are now submerged (images: Antarctica New Zealand).

Many research stations across Antarctica use lakes to supply their fresh water, with little research having been conducted into the potential consequences of this. Examples include Artigas Station (Lake Uruguay), Bellingshausen and Frei stations (Drinking Water Lake, fed from Kitezk Lake), Davis Station (Station Tarn - a seawater pond that is desalinated and flushed with fresh sea water from time to time), Escudero Station (Laguna Las Estrellas) and Great Wall Station (Petrel Lake; Peter et al. Reference Peter, Buesser, Mustafa and Pfeiffer2008). Despite concerns having been expressed during the international environmental impact assessment process required under the Protocol concerning use of water from pristine lakes to supply Bharati Station, the suggested alternative of reverse osmosis was not adopted (India 2007). In contrast, plans to use lake water from two closed-basin lakes to supply the new Turkish research station to be constructed on Horseshoe Island, Marguerite Bay, were shelved after concerns were raised regarding the lakes during the review process, resulting in a reverse osmosis plant using sea water now being incorporated into the station design (CEP 2021).

Large-scale construction work has also negatively impacted lakes, with, for example, the crustacean B. poppei becoming locally extinct at Rothera Point, Adelaide Island, following extensive quarrying for rock to construct a 900 m airstrip in the early 1990s that led to the draining of a small lake. The construction of a 2.2 km-long airstrip at Boulder Clay, Terra Nova Bay, resulted in the destruction of perennially ice-covered ponds and their associated biodiversity (Cannone et al. Reference Cannone, Pont and Malasi2021).

Direct impacts on freshwater bodies have also occurred as an inevitable consequence of scientific research. One example is the construction of a weir, flumes and other structures in the Dry Valleys to facilitate long-term hydrological studies (Wharton & Doran Reference Wharton and Doran1998, Chinn & Mason Reference Chinn and Mason2016). Within ASPA 126 Byers Peninsula, which was designated to protect primarily the freshwater bodies within the area, Pertierra et al. (Reference Pertierra, Hughes, Benayas, Justel and Quesada2013) reported sensors, plots and markers that were not maintained and were probably abandoned, potentially breaching the terms of permits required under the Protocol for access to the ASPA. They noted that scientists undertaking research in areas such as ASPAs protecting freshwater bodies that could be considered pristine face the paradox that the research itself may cause environmental degradation at some level, and they concluded that ‘scientific benefits in these sensitive areas need to be balanced against environmental impacts to safeguard their future scientific value’. Participants at a US National Science Foundation workshop (Wharton & Doran Reference Wharton and Doran1998) on lakes in the Dry Valleys specifically recommended measures to minimize the effects of research activities on these sensitive ecosystems. There is an urgent need to retrieve out-of-use experimental material distributed throughout ice-free regions in Antarctica that may have a measurable effect on freshwater ecosystems. Greater care is needed to ensure that the management of markers or structures follows the regulations of management plans, including removal, and that these are correctly and permanently identified.

The current status of protection for inland waters

Under the Protocol, area protection is achieved through ASPAs, Antarctic Specially Managed Areas (ASMAs) and Historic Sites and Monuments (HSMs). ASPAs represent the highest level of spatial environmental protection currently possible under the Antarctic Treaty System and can contain zones where access is further restricted or, in some cases, prohibited with effectively no access. As part of the process for an area to be designated as an ASPA, a management plan must be drafted, assessed by the CEP and adopted by the ATCM (CEP 2000). Entry to a designated ASPA is only allowed in accordance with a permit issued by an appropriate national authority.

We examined the management plans for all 75 of the currently designated ASPAs (available at https://ats.aq/devph/en/apa-database) to determine whether each makes any acknowledgement of the presence of inland water bodies and their values. Currently, only two of the 75 ASPAs have been designated explicitly to protect inland aquatic systems (ASPA 119 (Davis Valley and Forlidas Pond, Dufek Massif) and ASPA 126 (Byers Peninsula, Livingston Island); Table I & Supplemental Appendix 1). Fourteen additional ASPAs make some reference to aquatic systems within their ‘Descriptions of Values to be Protected’.

Table I. Representation of inland waters within existing Antarctic Specially Protected Area (ASPA) management plans.

a In some cases the text of the management plan made only the briefest mention of aquatic systems, but we opted for an inclusive approach to arrive at 26 ASPAs in this category.

Although inland waters of some kind are captured within the boundaries of a further 26 ASPAs, they are not recognized as values within the text of their management plans. We recommend a re-evaluation of these to determine whether their contained water bodies do represent regional biodiversity and/or contain particular values. If so, their management plans require modification to reference these systems as values, recognize their intrinsic importance and include appropriate management requirements.

In an encouraging development, at CEP XIV in Berlin in 2022, the Committee promoted the development of management plans for three potential ASPAs, all listing ‘lakes’ as values to be protected (Belgium 2022, Belgium et al. 2022, Germany & United States 2022). Eventual designation of these new ASPAs (through agreement by the ATCM) will enhance the geographical and lake-type representation within the ASPA framework. The locations are recommendations from researchers on the basis of outstanding scientific and environmental values and in two cases include reference to regional representativeness.

Discussion

As stated earlier, Article 3.1 of Annex V to the Protocol requires the identification of values to provide the underpinning reason(s) for protection under ASPA designations. Here, we have provided evidence that inland aquatic ecosystems hold significant values, yet, of the 75 current ASPAs, we found those values to be included amongst the primary reasons for designation in only two, and they were included as additional values for protection in a further 14 (Table I, Supplemental Appendix 1). Given the significance of inland aquatic ecosystems, it is important to consider the reasons for the apparent paucity of specific protection under the existing ASPA framework in order to identify potential complexities relating to their protection and then to suggest ways to incorporate the special characteristics of Antarctica's inland waters.

Why is there currently little representation of inland water values in ASPAs?

Given that most of the existing protected areas were nominated by Treaty Parties on the basis of recommendations from researchers, any bias in focus of ASPAs may reflect the amount and profile of research activity in different fields (Coetzee et al. Reference Coetzee, Convey and Chown2017, Hughes & Grant Reference Hughes and Grant2017, Wauchope et al. Reference Wauchope, Shaw and Terauds2019). A major review of Antarctic biodiversity (Convey et al. Reference Convey, Chown, Clarke, Barnes, Bokhorst and Cummings2014) cited more than four times as many papers on terrestrial ecosystems than on inland waters.

Access and sampling difficulties for inland water bodies can also make it difficult to fully appreciate biodiversity issues in inland waters, which have a range of sub-habitats that are often under thick, perennial ice cover. For example, Lake Joyce in the McMurdo Dry Valleys is the type (and only known) location for the copepod D. joycei (Fig. 4). Its existence was unknown despite several decades of research on the lake because its specific habitat (epibenthic) was not examined (Karanovic et al. Reference Karanovic, Gibson, Hawes, Andersen and Stevens2014). Linked to this is the issue highlighted above that much Antarctic biodiversity and the extent of endemism have only begun to be appreciated since the recent incorporation of molecular tools into Antarctic research.

Fig. 4. Examples of human threats to inland water bodies. a. Many lakes are used as water supplies. Historically, Pumphouse Lake on Signy Island was used to supply whaling vessels (image: authors). b. Dry Valley drilling programme operating on top of Don Juan Pond, the only known location for the mineral antarcticite (image: Antarctica New Zealand). c. Vacuuming oil-contaminated soil from near Lake Dingle, Vestfold Hills (image: T. Spedding). d. Pumping contaminated groundwater from Lake Vanda field station (image: authors). e. Contaminated sites (cross-hatched areas) in the vicinity of inland water bodies on Fildes Peninsula (modified after fig. 4.2-5 from Peter et al. Reference Peter, Buesser, Mustafa and Pfeiffer2008). f. Dismantling of Lake Vanda Station in 1992 (image: authors).

A further reason for this may relate to a key axiom in limnology that freshwater management requires management of catchments. Moss (Reference Moss2018) pointed out that the conservation of freshwater values, including biodiversity, ‘is not possible without control of the way the catchment is managed’. This requirement places a different perspective on the size of ASPAs that are needed to protect inland waters, challenging a system that tends to protect small areas that bound defined features supporting specific values.

Challenges to the prioritization of inland waters for protection

Biodiversity and ecosystem protection are particularly challenging under a regime combining accelerating climate change along with increases in direct human impact as numbers of visitors continue to increase (Convey & Peck Reference Convey and Peck2019). These form a backdrop to the prioritization of areas for conservation in Antarctica (Hughes et al. Reference Hughes, Convey and Turner2021). Within this context, prioritization of inland waters for protection also requires the application of objective and systematic approaches that are challenging in data-poor environments. We suggest that developing a framework for the prioritization of protected areas in Antarctica requires attention to be paid to a range of linked concepts: representativeness, vulnerability, irreplaceability and persistence.

The concepts of representativeness, vulnerability and persistence as evaluation criteria for a conservation framework were suggested by Margules & Pressey (Reference Margules and Pressey2000) in their seminal paper on the systematic designation of protected areas for optimal conservation values. These were expanded by Brooks et al. (Reference Brooks, Mittermeier, da Fonseca, Gerlach, Hoffmann and Lamoreux2007) in a review of systematic priorities in conservation that linked irreplaceability to vulnerability. Pressey & Bottrill (Reference Pressey and Bottrill2009) similarly developed a systematic conservation planning tool, which Coetzee et al. (Reference Coetzee, Convey and Chown2017) adapted for Continental Antarctica. We note that the criteria developed by the CEP to guide protected area designation in Antarctica are not dissimilar to those of Margules & Pressey (Reference Margules and Pressey2000), with a focus on representativeness, diversity, distinctiveness, ecological importance, degree of interference, value to science and monitoring (CEP 2000). The CEP criteria are designed to accommodate a suite of values other than environmental ones and are thus subtly different, but, given this overall convergence, we explore here the applicability of the Margules & Pressey (Reference Margules and Pressey2000) criteria to Antarctic inland waters.

Representativeness

To provide a broad representation of the continent's inland waters, understanding the spatial scales of variability are important. Our review of habitat and biological variability has identified that, at present, while knowledge of the biogeography of inland waters across the continent is incomplete, there is evidence of endemism in some groups at continental, regional and local levels. We also demonstrated a link between habitat diversity and biological diversity, acknowledging a tendency for broad niche tolerance amongst most common species, and we suggest that habitat diversity is a useful proxy for the protection of biodiversity. At present, no bioregionalization of inland waters has been validated, apart from that of the Gressitt Line, and the tendency for national research programmes to work increasingly close to existing facilities (Chignell et al. Reference Chignell, Myers, Howkins and Fountain2021) makes this unlikely to occur without targeted international efforts to better understand Antarctic inland biodiversity. To facilitate a representative protected area framework, the conservative approach may therefore be to target all ACBRs, incorporating our knowledge of aquatic biogeography where possible, and to target a diversity of habitats within each region. Existing mapping and examination of satellite imagery show that there are inland water bodies in almost all of the ACBRs (Fig. 5), and we know from our recent high-resolution remote sensing study of the Dry Valleys ASMA (Hawes et al. Reference Hawes, Howard-Williams, Gilbert and Joy2021) that an order of magnitude more water bodies exist than current maps show. We recommend that further effort is devoted to better validating the distribution of inland water bodies across the continent using remote sensing tools (see also Salvatore et al. Reference Salvatore, Borges, Barrett, Sokol, Stanish, Power and Morin2020, Vanhellemont et al. Reference Vanhellemont, Lambrechts, Savaglia, Tytgat, Verleyen and Wyverman2021) and advocate for international efforts to coordinate continent-wide biodiversity assessments. There is also growing use of remotely piloted aircraft systems (drones) within research programmes, and these offer opportunities for resource mapping at high resolution.

Fig. 5. Map of inland water bodies and existing Antarctic Specially Protected Areas and Antarctic Conservation Biogeographic Regions (the latter from Terauds & Lee Reference Terauds and Lee2016). ‘Mapped lakes’ are those in the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research digital database v7.3. ‘Unmapped lakes’ are those identified in a manual search of Google Earth images, targeting ice-free areas with few mapped lakes. The search is not exhaustive and should be viewed as evidence only of the extent to which inland waters are underreported. Subglacial lakes are not included.

Vulnerability

Within Antarctica, we have shown how the vulnerability of ecosystems to the direct effects of human activities largely relates to infrastructure construction and operation, the activities of national programmes, tourism and disruptive research activities, and such vulnerability is probably greatest in the vicinity of station and research sites (e.g. Fig. 4; Chignell et al. Reference Chignell, Myers, Howkins and Fountain2021). In Antarctica, the provisions of Article II of the Protocol seek to avoid anthropogenic impacts and should mitigate direct human interference. We acknowledge that in practice this is often not the case and recommend the careful evaluation of the values associated with inland waters within human operational footprints.

The prevalence of microbial diversity in Antarctica places a different lens on vulnerability in comparison with warmer regions of the Earth, where conservation is often directed towards larger organisms, which are readily recognizable, including non-native taxa (Cowan et al. Reference Cowan, Chown, Convey, Tuffin, Hughes, Pointing and Vincent2011). It can be argued that the greatest vulnerability should be allocated to locations least likely to have already been compromised by human activity. Vulnerability here is measured in terms of the irreplaceable consequences of change rather than its probability, and we argue that the highest priority for conservation should go to these pristine reservoirs of biodiversity rather than to regions closer to research facilities where unseen microbial contamination may already have occurred. Few pre-construction environmental assessments include rigorous characterization of aquatic microbial diversity, and, given the prevalence of molecular genetic techniques for biodiversity surveys (e.g. eDNA), we recommend future pre-development environmental assessments include such techniques.

Persistence (in an era of rapid change)

Sensitivity to hydrological change means that climate is a key issue when considering the persistence of biodiversity values and long-term survival of species and habitats in Antarctica. Our review has demonstrated how Antarctic inland waters are temporally variable, over timescales from seasonal through to full glacial cycles.

The literature on alterations to ecological systems resulting from climate change is indicating the occurrence of transformational change across the globe (Jackson Reference Jackson2021). Turner et al. (Reference Turner, Calder, Cumming, Hughes, Jentsch and LaDeau2020) referred to the occurrence of ’abrupt change in ecological systems’ and that many changes are associated with tipping points or critical transitions that lead to ‘self-sustaining change’ that cannot always be predicted (Turner et al. Reference Turner, Calder, Cumming, Hughes, Jentsch and LaDeau2020). A pertinent example here is the rapid expansion of summer moulting male fur seal numbers in the South Orkney Islands (Waluda et al. Reference Waluda, Gregory and Dunn2009) and along the west coast of the Antarctic Peninsula in recent decades. This expansion in seal numbers is probably in part a result of protection from human harvest following their extensive overexploitation in the Southern Ocean ecosystem in the late 18th and 19th centuries, and it has caused eutrophication and severe damage to coastal terrestrial habitats and freshwater lakes and streams (Smith Reference Smith1988, Hawes Reference Hawes, Kerry and Hempel1990, Favero-Longo et al. Reference Favero-Longo, Cannone, Worland, Convey, Piervittori and Guglielmin2011, Convey & Hughes Reference Convey and Hughes2023).

In considerations of ‘Persistence’ as a criterion for protected area designation, there will be a need for relatively precise descriptions of biodiversity values and their vulnerability to change (Hughes et al. Reference Hughes, Convey and Turner2021). Elements of the biota of most inland waters have survived multiple glaciation cycles and, while many are classed as ‘extremotolerant’, most are tolerant of wide ranges of more normal temperature, salinity and irradiance (Vincent & James Reference Vincent and James1996, Jungblut et al. Reference Jungblut, Wood, Hawes, Webster-Brown and Harris2012). Given this physiological flexibility, the extent to which climate change per se represents an immediate threat to species persistence is as yet little understood. Changes to functional attributes due to changing climate may challenge some microbial assemblages, such as increased rates of growth and activity of fungi that may adversely affect community structure (Velazquez et al. Reference Velasquez, López-Bueno, Aguirre de Cárcer, de los Ríos, Alcami and Quesada2016). Conversely, step change reductions in function may occur if temperature thresholds are breached (Misiak et al. Reference Misiak, Goodall-Copestake, Sparks, Worland, Boddy and Magan2021). Additionally, we recognize that the synergistic effect that climate amelioration may have on the arrival of organisms able to expand their ranges within or to the continent does suggest that climate change may affect vulnerability as much as persistence.

Protection of single water bodies vs catchments

In the case of water body protection there is a need to recognize, firstly, entire functioning ecosystems to ensure the long-term maintenance of ecological processes and, at the very least, the inclusion of surrounding buffer zones or catchments (Keys et al. Reference Keys, Dingwall and Freegard1988, Moss Reference Moss2018). This is singularly important if ponds, lakes, streams and their water sources are to be protected effectively, and an ASPA closely surrounding a water body may not deliver appropriate protection of values. In many parts of Antarctica, networks of connected inland water bodies occur and, in such cases, protection of the complete catchment may be required. Incorporation of large size and altitudinal range within protected areas also offers some mitigation against changing climates as, for example, vertical migration of organisms to follow displacement of habitats may offset catchment warming.

This places a different perspective on the proposed size of future ASPAs incorporating inland waters. The current system of demarcation of ASPAs appears (possibly inadvertently) to be geared towards defining a minimal area required to protect defined value(s), and ~55% of ASPAs have an area of < 5 km2 (Hughes & Convey Reference Hughes and Convey2010). Adequate protection of inland water bodies and their catchments inherently requires larger areas to be designated. Within the existing ASPA system we recognize APSAs 119, 123, 126 and 147 as specific exemplars of how inland waters could be better protected using a catchment area approach.

Of these, ASPA 119 (Davis Valley and Forlidas Ponds, Dufek Massif) is one of only two ASPAs currently specifically designated to protect inland waters. It comprises two entire catchments and contains a range of inland water bodies that are representative of the site, and the water sources are protected. The management plan also describes how, by including the catchment, representative terrestrial biota is also protected (Hodgson et al. Reference Hodgson, Convey, Verleyen, Vyverman, McInnes and Sands2010, Reference Hodgson, Bentley, Schnabel, Cziferszky, Fretwell, Convey and Xu2012). In addition, the area is described as of high wilderness and aesthetic value. Similarly, ASPA 123 (Barwick and Balham Valleys, South Victoria Land), while not specifically aimed at inland water protection as the primary value, is designated for ‘[p]rotection on a catchment basis … to provide greater representation of the ecosystem features, and also facilitates management of the Area as a geographically distinct and integrated ecological system’.

ASPA 126 (Byers Peninsula) is one of the largest ice-free areas in the Antarctic Peninsula region and is considered a hotspot for terrestrial and freshwater diversity (Toro et al. Reference Toro, Camacho, Rochera, Rico, Bañón and Fernández-Valiente2007, Quesada et al. Reference Quesada, Camacho, Rochera and Velázquez2009, Rochera & Camacho Reference Rochera and Camacho2019). The ASPA contains lakes, ponds, streams, rivers, seepages and wetlands, which represent most of the habitat diversity in the area, and the biological diversity covers all known groups in Antarctica. The management plan aims to minimize cumulative impact on diverse values (freshwater ecosystems, terrestrial flora and fauna, vegetation, microbial mats, marine avifauna, palaeoenvironments, archaeological remains, geological formations and fossiliferous strata).

Finally, ASPA 147 (Ablation Valley and Ganymede Heights) is located on Alexander Island, the largest island off the western coast of Palmer Land, Antarctic Peninsula. The site is one of the largest ice-free ablation areas in Maritime Antarctica, making it an area of outstanding scientific interest. As well as protecting geological and geomorphological features, the ASPA boundary encompasses the catchment areas of two epishelf lakes, which contact the saline waters of George VI Sound beneath George VI Ice Shelf, as well as numerous other lakes and ponds.

The role of classifications

Prioritization of areas for conservation, such as ASPAs, may be underpinned in a systematic way by an environmental classification. Classifications (e.g. ACBRs; Fig. 5; Nedbalova et al. Reference Nedbalova, Nyvlt, Kopacek, Obr and Elster2013, Hawes et al. Reference Hawes, Howard-Williams, Gilbert and Joy2021) facilitate the identification of locations that are likely to show similar biophysical properties and responses to human activity or management action. In particular, classifications allow for the inference of characteristics of unsampled locations that may potentially be identified through remote sensing. Hawes et al. (Reference Hawes, Howard-Williams, Gilbert and Joy2021) described how classifications of inland waters provide spatial frameworks to support environmental and conservation management needs by ordering, labelling and mapping geographical units with distinctive ecological (biotic and abiotic) characteristics in the McMurdo Dry Valleys ASMA. A classification system extended to include all types of Antarctic water bodies could enhance prioritization by representativeness and vulnerability and facilitate consideration of water bodies in unvisited areas.

A way forward

We have argued the need for a systematic approach to enable the appropriate protection of inland waters in Antarctica and noted the challenges this faces. We suggest that:

1) In the absence of comprehensive, high-quality biodiversity and biogeography data, a conservative approach is required that uses ACBRs to ensure representative coverage.

2) Goals are set to protect representative classes of inland water bodies from each ACBR that i) include the catchment, ii) either are or are close to pristine and iii) are sufficiently distant from stations and other facilities to avoid casual visitation. Sites should also be designated so as to include areas known to host rare aquatic organisms or those with limited distributions. Existing ASPAs should be reviewed to determine whether they contain representative inland water bodies.

3) Consideration be given to the designation of ASPAs that better meet existing requirements under the Protocol to be ‘representative examples of major terrestrial, including glacial and aquatic, ecosystems and marine ecosystems’, including areas of restricted access, or to remain inviolate for significant periods of time to act as strategic investments in habitat and biological diversity for future generations of researchers.

4) Designation of such representative catchments may be best accomplished through a collaborative approach such as multi-party ASPAs (Hughes & Grant Reference Hughes and Grant2017), which may also assist in a move away from the reliance on individual researchers to champion ASPAs. Both the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR) and the CEP can also propose such ASPAs (but have not done so to date) and may offer suitable mechanisms.

5) Very-high-resolution remote sensing products could be used to identify likely areas in poorly documented ACBRs for potential inclusion for inland water protection (see Supplemental Appendix 2).

Coetzee et al. (Reference Coetzee, Convey and Chown2017) described 10 key steps in the development of a systematic conservation plan for all Antarctic inland habitats. These steps describe the process through stages of scoping, stakeholder engagement, identification of goals and objectives, setting targets and maintaining and monitoring of goals. Table II, based on the framework developed by Margules & Pressey (Reference Margules and Pressey2000), provides a set of steps specific to the development of a catchment-focused approach for inland water bodies, with suggestions as to how this could be achieved. We suggest that it be viewed alongside the system advocated by Coetzee et al. (Reference Coetzee, Convey and Chown2017), with which it shares many features.

Table II. Six-step guide (partly after Margules & Pressey Reference Margules and Pressey2000) to developing the systematic prioritization of Antarctic Specially Protected Areas (ASPAs) for application to inland waters in Antarctica managed under the framework for protected area designation through Annex V to the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty.

ACBR = Antarctic Conservation Biogeographic Region; ATCM = Antarctic Treaty Consultative Meeting; CEP = Committee for Environmental Protection.

Conclusions

Enhancing the protection of all aspects of the Antarctic environment builds on the commitments that the Parties have already made, including to systematically develop the ASPA framework. Doing this as effectively as possible helps to build resilience against future impacts, whatever and wherever they may be.

Our review of habitat and biological diversity highlights the importance of inland waters in all of their various forms to non-marine biodiversity in Antarctica, their underrepresentation in current ASPAs and their vulnerability to multiple sources of disturbance, from climate change to non-native taxa and direct human impact. They must form a more significant component of a systematic ASPA framework than has been the case to date. The poor representation of inland waters as primary values within existing ASPAs provides an example of why a systematic mechanism is required.

When considering the designation of protected areas for the conservation or protection of inland waters, we stress the need for the consideration of catchment-scale processes. Future ASPAs designated with primary or even secondary values to protect inland waters must be sufficiently large to allow this. Priority should be given to systems that are pristine or nearly so, and are likely to stay so, along with the development and validation of ACBRs for inland aquatic systems to ensure systematic designation.

Catchment-scale ASPAs that cover inland water values will, in most cases, also protect representative terrestrial ecosystem values as well as geological, glacial and wilderness values. Larger areas covering substantial altitudinal ranges are more likely to provide resilience to climate change.

We have developed a framework (Table II) to facilitate the development of a systematic approach to the development of a protected area strategy for inland waters. This system builds on progress to date within the ATCM environmental management system and, with appropriate modifications, will be applicable to other types of biological resources.

We recognize that exceptions requiring the consideration of individual water bodies and their water sources may arise where aquatic systems demonstrate unique aspects or are close to facilities where the risks from direct human activities, including that of the introduction of non-native species, are likely to be highest. In such cases, the requirements defined in the Protocol to operate under procedures designed to minimize the impacts on and risks to such systems should be rigorously adhered to. Specifically, the construction of infrastructure should always consider the need to minimize impacts on inland water bodies.

While this paper specifically focuses on the need for the improved protection of inland waters, the underlying message is one of an urgent need for the application of a broader systematic approach in general to the development and prioritization of Antarctic protected areas.

Acknowledgements

We thank the New Zealand National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (CH-W) and our colleagues around the world for many discussions that have stimulated our thinking on the issues covered in this manuscript. Two anonymous reviewers provided commentary on this manuscript, which has benefitted from incorporation of their suggestions. This work contributes to the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) Polar Science for Planet Earth ‘Biodiversity, Evolution and Adaptation’ Team (PC) and the BAS Environment Office Long Term Monitoring and Survey project (EO-LTMS) (KAH), which are supported by NERC core funding, and the ‘Integrated Science to inform Antarctic and Southern Ocean Conservation’ (Ant-ICON) research programme of the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR).

Financial support

We thank the New Zealand Antarctic Science Platform for support through MBIE Contract ANTA1801 (IH and NG).

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the planning and gathering of information for this review and all contributed to the preparation of the manuscript.

Supplemental material

Two supplemental appendices and a supplemental figure will be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954102022000463.