Introduction

The configuration of the West Antarctic ice sheet (WAIS) changes drastically over a typical glacial–interglacial cycle. During interglacials, such as the Sangamon 125 (ka B.P.), grounded ice may have disappeared completely (Reference MercerMercer 1968). During a glacial maximum, ice grounds from interior regions to the continental-shelf edge (Reference Kellogg, Truesdale and OstermanKellogg and others 1979, Reference Anderson, Kurtz, Domack and BalshawAnderson and others 1980, Reference ElverhoiElverhøi 1981,Reference Stuiver, Denton, Hughes, Fastook, Denton and Hughes Stuiver and others 1981).

The sporadic fluctuations of the WAIS raise three questions concerning its formation: (i) how does the ice sheet form, (ii) how long does it take to form, and (iii) what effects do changes in environmental conditions such as sea-level, surface accumulation rate, and flow into the region from East Antarctica have on its formation? Two mechanisms have been suggested to explain how the WAIS grounds in regions where the bed is initially below sea-level. In the first, grounded ice in regions where the bed is above sea-level gradually thickens and flows laterally into regions where the bed is below sea level (Reference Bentley and OstensoBentley and Ostenso 1961). In the second, ice-shelf cover gradually thickens vertically until the ice grounds (Reference WexlerWexler 1961,Reference Hughes Hughes 1982). A combination of these two mechanisms is also possible.

The time required to form the WAIS is important because environmental conditions vary periodically with the Milankovitch cycle. The ice sheet, then, must be able to form during the possibly brief time interval of favorable environmental conditions. Environmental conditions also control the geographic distribution of grounding. A drop in sea-level caused by ice-sheet formation in the Northern Hemisphere, for example, reduces the minimum ice thickness necessary to ground ice in regions where the bed is below sea-level.

These aspects of WAIS formation have been addressed by Reference Lindstrom and MacAyealLindstrom and MacAyeal (1987), using a time-dependent numerical ice-shelf model which simulates WAIS growth from an initial 20 m thick floating ice cover over regions where the isostatically adjusted bed is below sea-level. The study was conducted only to test the general process of WAIS formation, not to model any particular geologic time frame. In the model, mass is added to the ice-shelf region by surface accumulation and basal freezing. Ice-shelf mass losses are the result of seaward ice-front calving, basal melting, and grounding (grounded ice that developed during the experiment was assumed to be stagnant, and thus without means of mass wastage). A number of runs were made to test the effects which changes in sea-level, surface accumulation rate, and the amount of ice flowing from East Antarctica into West Antarctica have on WAIS formation. Results of the study showed that an incipient WAIS could form under many realistic environmental conditions within 4000 years. Lowering of sea-level was found to be the major environmental factor which determined how much grounding occurred and how long the ice took to ground.

The general characteristics of WAIS formation were examined by Lindstrom and MacAyeal (1987), without taking into account geographic detail relevant to the sequence of grounding during the formation period. In this paper, I analyze one of the model experiments conducted by Lindstrom and MacAyeal (1987) to determine geographic sequences of grounding and the intermediate patterns of ice-shelf flow. The model experiment so analyzed is described in Lindstrom and MacAyeal (1987). Surface and basal temperatures are −20° and −1.7°C respectively, sea-level is lowered by 100 m, the surface accumulation rate is 0.2 m a−1, basal melting is zero, and no ice flow enters the region from East Antarctica. These environmental conditions were chosen because the temperatures and accumulation rate are similar to those of present-day Antarctic ice shelves (Reference Giovinetto and BentleyGiovinetto and Bentley 1985,Reference Budd, McInnes, Jenssen, Smith, Veen van der and OerlemansBudd and others 1987). Flow into the region from East Antarctica was not allowed, so that a test could be made of the grounding mechanism of Wexler (1961) and Hughes (1982) mentioned above. After discussing the results of this model run, I suggest how grounded-ice dynamics may alter the picture of WAIS formation and how the pattern of sedimentation might be affected.

Model and Run Specifications

The mathematical equations used in the model are presented in Reference Lindstrom and MacAyealLindstrom and MacAyeal (1986, 1987). In short, the force-balance equation, along with a constitutive equation relating stress to strain-rate (Glen’ s flow law), is used to compute a velocity field over the ice-shelf region. This velocity field is used in the mass-balance equation in order to determine a new thickness field for the next time step. The new ice thickness for each ice-shelf element is then compared with the sea-bed depth for that element. If the ice draft is greater than the bed depth, it is assumed that the element has grounded, and its specifications are changed accordingly. Environmental conditions, such as basal and surface temperatures (that affect ice rheology) and accumulation rates (that affect mass balance), are incorporated in the model as boundary conditions. Sea-level is lowered in the model by decreasing the bed depths.

Fig. 1. Fig. 1. Configuration of present West Antarctic ice cover. The shaded regions represent ice shelves and ice streams, and the solid lines mark the boundaries of the permanent ice cover and open sea. The contours represent the grounded-ice thickness in meters. The dashed line marks the continental-shelf edge. Derived from sheet 4 of Reference DrewryDrewry (1983).

The major assumption of the model is that once ice grounds in the West Antarctic region it becomes stagnant. This assumption was made for the following reasons. First, a primary purpose of the study was to investigate how grounding would proceed by ice-shelf thickening alone, with no contribution from grounded-ice flow (a test of the grounding mechanism proposed by Wexler (1961) and Hughes (1982)). Secondly, the results indicate that with the environmental parameter values specified above, an incipient grounded WAIS forms within 4000 years. This time-scale is not sufficiently long for the thickness and surface slope of grounded ice to become large enough to make grounded-ice motion significant. The assumption is thus valid until the grounded-ice thickness and surface slope do become large enough to make grounded-ice motion significant.

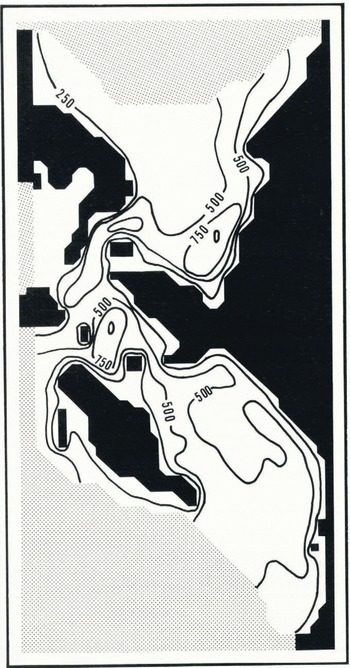

The present West Antarctic geographic configuration is shown in Figure 1. The initial model grid, Figure 2, represents this area as it would appear if the present ice cover were removed and isostatic adjustment of the bed occurred. Black, white, and shaded regions in Figure 2 represent grounded and floating ice and the open sea beyond the continental shelf respectively. Floating ice cover 20 m thick extends to the continental-shelf edge. Contours indicate the isostatically adjusted bed depth in meters below present sea-level (sheet 6 of Drewry 1983).

Fig. 2. Fig. 2. Initial configuration of the grid used in the West Antarctic study. The shaded pattern represents open water, the black region represents grounded ice, and the white area represents floating ice. The contours represent sea-bed depths in meters below sea-level, as they would exist if the present West Antarctic ice cover were removed and isostatic rebound occurred. These are smoothed from sheet 6 of Drewry (1983).

Fig. 3. Fig. 3. Grounded region and ice-shelf flow-line pattern of West Antarctica after 1000, 2000, 3000, and 4000 years.

(a) 1000 years. Grounding has occurred over major parts of Ronne and Larsen ice shelves and parts of the Bellingshausen Sea.

Fig. 3b. (b) 2000 years. Ronne Ice Shelf has grounded completely. Ice from Ellsworth Land is diverted to the Filchner Ice Shelf region. A small patch of grounding has formed up-stream of the present Ross Ice Shelf grounding line.

Ice Grounding and Flow-Line Patterns

The model was run through a 5900 year time simulation using 50 year time steps. Figure 3a-d shows the ice shelf and grounded ice-sheet configuration and ice-shelf flow lines after 1000, 2000, 3000, and 4000 years respectively. After 1000 years (Fig. 3a) significant grounding occurs over the shallow bed regions of the Ronne (west of Berkner Island) and Larsen ice-shelf regions and parts of the Bellingshausen Sea. Ice from interior regions does not flow toward Larsen Ice Shelf and the Bellingshausen Sea, so grounding in these areas does not have a regional impact on the ice-flow pattern. Ice draining from Ellsworth Land, however, does flow toward the Ronne region, so grounding here affects regional flow. The Ronne grounding diverts Ellsworth Land ice flow through the Filchner region (the continental shelf east of Berkner Island) and into the eastern Weddell Sea, whereas today most of this ice drains through the Ronne region.

The Ronne region grounds completely after 2000 years (Fig.3b). At this time, all ice from Ellsworth Land is channelled through the Filchner region, where grounding is suppressed by a deep bed (Fig.2). An isolated grounded patch develops just up-stream of the present Ross Ice Shelf grounding line. This has a local rather than regional effect on the flow pattern, because it is located far back from the calving front. Ice forced to diverge around the grounded patch in the Ross region converges again a short distance down-stream of the patch. Similar conditions exist after 3000 years (Fig.3c), with slightly more grounding at this later time.

By 4000 years an ice-shelf equilibrium condition exists according to the assumptions made by the model. All regions have grounded except those in the Ross Sea, Filchner Ice Shelf, up-stream of Thwaites Glacier, Getz Ice Shelf, and a small area east of the Antarctic Peninsula. Ice east of the Antarctic Peninsula and over Getz Ice Shelf does not ground because of its proximity to the calving front and limited ice-mass input. Ice over the Ross Sea, up-stream of Thwaites Glacier, and the ice of Filchner Ice Shelf does not ground because of its proximity to the calving front and underlying deep sea bed.

Grounding up-stream of Thwaites Glacier, which occurs at present, and to the continental-shelf edge over the Ross Sea and Filchner areas, for which there is field evidence during glacial periods (Kellogg and others 1979, Stuiver and others 1981,Reference Elverhoi Elverhøi 1984), must occur after adjacent grounded-ice flow becomes large enough to deliver significant ice volume into the remaining ice shelf. As the driving stress increases and grounded-ice flux becomes significant, Ellsworth Land ice should still flow toward the Filchner region, as the surface elevation along its former ice-shelf flow-line path will be much lower than that of adjacent ice.

Fig. 3c. Fig. 3. Grounded region and ice-shelf flow-line pattern of West Antarctica after 1000, 2000, 3000, and 4000 years.

(c) 3000 years. The pattern of grounding is similar to that at 2000 years, only now the grounded region has expanded.

Fig. 3d. (d) 4000 years. The Ellsworth Land region has grounded completely. An equilibrium state according to the assumptions made by the model has been attained on the assumption that grounded-ice dynamics are negligible. The letters A and Β correspond to the positions of points A and Β in Figure 4.

Sedimentation and Erosion

Glacial erosion and sedimentation would be insignificant during the time interval of the model run, because an ice shelf does not erode a bed and the grounded-ice thickness and surface slope are still too small to cause grounded-ice motion. This early ice-sheet configuration, however, should influence the grounded ice-flow pattern which will develop once the ice thickness and surface slope become large enough to have grounded-ice flow. If Ellsworth Land ice continues to flow toward the Filchner region (as suggested in the previous section, for example), minimal glacial erosion and deposition should occur over the Ronne region because of its small ice-volume flux. This may explain why the Ronne bed is shallow. In contrast, the large ice volume which I suggest would flow from Ellsworth Land to the calving front via the Filchner region favors glacial erosion. Elverhøi (1984) has found that the continental shelf in the Filchner region is deeply scoured.

A possible sedimentation-pattern development from Ellsworth Land to the south-eastern Weddell Sea calving front, bounded by points A and Β in Figure 3d, is presented in Figure 4a-e. The scenario begins at a time when the grounding line is at its equilibrium position, before grounded-ice dynamics become significant (Fig.4a). As grounded-ice flow becomes important, glacial till is deposited beneath the grounded ice and glacial marine sediments accumulate beneath the ice shelf and along the continental slope. A discussion of glacial marine sediments and sedimentation is to be found in Anderson and others (1980).

Most glacial marine sedimentation occurs near the grounding line and steadily decreases toward the continental slope (Elverhøi 1984). As the grounded-ice sheet expands, it overrides and compacts the glacial marine sediments and deposits a layer of glacial till (Fig.4b). If ice grounds on the edge of the continental slope and remains there for a substantial period (Fig.4c), the sediment-laden icebergs should deposit a thick glacial marine cover on the slope. As the grounding line recedes ((Fig.4d), (Fig.4e)), possibly due to a rise in sea-level at the end of a glacial period, glacial marine sediment is deposited on the till. A thick glacial marine-sediment cover should form down-stream of the grounding line whenever it remains stationary for a period during ice-sheet advancement or recession.

Fig. 4. Fig. 4. Possible sedimentation pattern resulting from the advancement and recession of grounded-ice cover. The locations of points A and Β correspond to the letters A and Β in Figure 3.

(a) The ice sheet is in a state of equilibrium according to the assumptions made by the model. Once grounded-ice flow is established, glacial till (represented by the blocky pattern) is deposited beneath grounded ice, and glacial marine sediments accumulate beneath the ice shelf and over the continental slope. Most glacial marine sedimentation occurs near the grounding line.

Fig. 4b. (b) The grounded-ice cover has advanced seaward. The glacial marine sediments covered by grounded ice are compacted (represented by an oval pattern) and are overlain by a cover of till.

Fig. 4c. (c) The ice has advanced to the continental-shelf edge. If it remains at that position for a significant period, a thick layer of glacial marine sediment will accumulate on the continental slope.

Fig. 4d. (d) Grounding-line recession. A layer of glacial marine sediment covers the till.

Fig. 4e. (e) The grounding line has returned to its original position.

Anderson and others (1980) observed that Ross continental-shelf sediments have a finer matrix and contain more marine fossils than those of the Weddell continental shelf. This suggests that Ross sediments have a more strongly glacial marine character than Weddell sediments and indicates that there may have been grounded-ice cover for a longer period over the Weddell region than the Ross region. The almost complete lack of grounding in the Ross region before grounded-ice dynamics become significant (Fig.4e) supports this contention.

Conclusions

The model simulation performed in this study suggests that ice grounds over large parts of West Antarctica within 4000 years of a drop of 100 m in sea-level, even when grounded-ice flow is neglected. Early grounding over the Ronne region forces ice from Ellsworth Land to flow eastward through the Filchner region. It is suggested that grounding occurs in the Ross and Filchner regions and up-stream of Thwaites Glacier after interior grounded ice commences flowing.

Glacial erosion and sedimentation will be negligible until grounded-ice flow becomes significant. Thus the glacial geologic “window” on WAIS formation that the ice-shelf mechanism provides may be inherently uninformative. It is postulated that erosion and sedimentation will be considerable along the path from Ellsworth Land to the Filchner region and minimal over the Ronne region. It is difficult for ice to ground over the Ross region, so it will contain a higher proportion of glacial marine sediments than it does over the Weddell region.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this project was provided by U.S. National Science Foundation grant DPP-8401016. I thank D.R. MacAyeal, R.G. Grumbine, M.M. Monaghan, T.B. Kellogg, T.J. Hughes, G.H. Denton, and an anonymous reviewer for helpful suggestions and criticisms throughout the span of this project.