Implications

To breed grazing ruminants with reduced methane emissions, we first need to demonstrate that there is repeatable individual variation in this trait and that a portion of this variation is genetically inherited. This study has provided evidence for both even after adjustment for intake. The portion of the variation that was independent of intake showed no unfavourable genetic relationships with the production traits that were measured in these animals. These results suggest that it may be feasible to breed ruminants with lower methane emissions.

Introduction

Rumen methanogenesis results in the loss of 6% to 10% of gross energy intake and globally is the single most significant source of anthropogenic methane (CH4) emissions. This source represents a major share of New Zealand's total greenhouse gas emissions (Cottle et al., Reference Cottle, Nolan and Weidemann2011; Pinares-Patiño et al., Reference Pinares-Patiño, McEwan, Dodds, Cárdenas, Hegarty, Koolaard and Clark2011c; Clark, Reference Clark2013). One option to mitigate these emissions is to genetically select for ruminants that emit less CH4. There is currently limited evidence about the genetics of this trait and its relationship with other production traits including feed intake. Recent extensive reviews of rumen CH4 formation by Janssen (Reference Janssen2010) and Clark (Reference Clark2013) indicated that altering rumen hydrogen (H2) concentrations affects CH4 emissions, and there is limited evidence showing that emissions are positively correlated with lower rumen flow rates and higher acetate/propionate ratios (Pinares-Patiño et al., Reference Pinares-Patiño, Ulyatt, Lassey, Barry and Holmes2003).

Pinares-Patiño et al. (Reference Pinares-Patiño, Ebrahimi, McEwan, Clark and Luo2011a and Reference Pinares-Patiño, McEwan, Dodds, Cárdenas, Hegarty, Koolaard and Clark2011c) presented results that showed that individual CH4 emissions expressed as g CH4/kg dry matter intake (DMI) is a repeatable trait across both ages and diets and that it is also accompanied by changes in rumen outflow rates. Similarly, preliminary studies have shown a repeatable, and in some a significant genetic, component to CH4 emissions, albeit often compromised by lack of intake measurements ( Hegarty and McEwan, Reference Hegarty and McEwan2010; Hegarty et al., Reference Hegarty, Alcock, Robinson, Goopy and Vercoe2010; Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Goopy, Hegarty and Vercoe2010 and Reference Robinson, Bickell, Toovey, Revell and Vercoe2011; Goopy et al., Reference Goopy, Woodgate, Donaldson, Robinson and Hegarty2011; Garnsworthy et al., Reference Garnsworthy, Craigon, Hernandez-Medrano and and Saunders2012). Specifically, the available parameter estimates are very limited in their nature, have low accuracy and are often compromised by factors intrinsic to the measurement technique.

Several modelling studies have also been undertaken using assumed parameters which suggest that high implicit carbon costs (CO2 equivalent or (CO2-e)) would be required to stabilise CH4 emissions while increasing productivity even when CH4 emissions and feed intake are measured (Cottle et al., Reference Cottle, Nolan and Weidemann2011; Cottle and Connington, Reference Cottle and Connington2012; Ludemann et al., Reference Ludemann, Bryne, Sise and Amer2012). These authors also uniformly suggested that improvement of this trait is best expressed to end users as emission per unit of animal product. The objective of this study was to accurately determine the genetic parameters of CH4 emissions and their genetic correlations with key production traits in sheep using respiration chambers where feed intake was measured and CH4 emissions monitored accurately over several days, while a standard diet was fed. It is part of a larger initiative to create divergent selection lines for this trait so as to understand the anatomical, physiological and microbiological as well as productivity changes that accompany selection for this trait.

Material and methods

All experimentation conducted was approved by AgResearch's Invermay and Palmerston North Animal Ethics committees. These included but were not restricted to applications 11930, 11975, 12206, 12233, 12241, 12324, 12414. The experiment was conducted at the Ulyatt-Reid Large Animal Facility of AgResearch Grasslands Research Centre in Palmerston North, New Zealand and CH4 was measured in respiration chambers of design and methodology as described by Pinares-Patiño et al. (Reference Pinares-Patiño, Ebrahimi, McEwan, Clark and Luo2011a and Reference Pinares-Patiño, Hunt, Martin, West, Lovejoy and Waghorn2012).

In total, 1225 animals were measured in respiration chambers between 5 and 10 months of age (30 to 40 kg live weight (LW); Supplementary Material 1). The animals were progeny of 99 maternal dual-purpose sires generated by the New Zealand industry progeny test program (McLean et al., Reference McLean, Jopson, Campbell, Knowler, Behrent, Cruickshank, Logan, Muir, Wilson and McEwan2006). The sires consisted of Coopworth, Romney, Perendale, Texel and Composite breeds, where the latter breed consisted primarily of combinations of the former breeds with additional infusions of Finn and East Friesian, and all rams were mated to Composite ewes. The progeny were generated in five separate, but genetically linked flocks and were born in 2007, 2009, 2010 and 2011. The majority of the animals selected to be measured were female with the exception of 96 males born in 2009 and a small number of males born in one flock in 2010 and 2011. After the initial measurement small numbers of extreme animals selected on the basis of g CH4/kg DMI (n = 20 born 2007, and n = 45 born 2009) were repeatedly measured for two additional consecutive years (at ∼16 and 28 months of age).

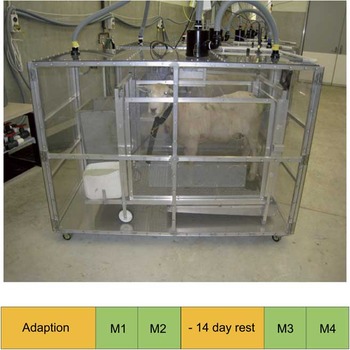

The CH4 measurements have been previously described by Pinares-Patiño et al. (Reference Pinares-Patiño, Ebrahimi, McEwan, Clark and Luo2011a). The chambers and brief measurement protocol used are outlined in Figure 1. Animals were acclimatised in pens for 21 days to a standard lucerne pellet diet (19% CP, 43% NDF and 10 MJ ME/kg dry matter). This was followed by two measurement rounds (R1 and R2) in respiration chambers with a 10 to 15-day interval in-between in the pens. Methane emissions were measured for 2 or 3 days consecutively in each round. Individual animal DMI was measured in metabolic crates during each round (4 days) and then in respiration chambers (2 days); feeding level was based on LW and was estimated as 2.0 times maintenance requirements. Animals were fed in two equal-sized meals at 9 am (hour 0) and 3 pm (hour 6) daily. Both in R1 and R2, individuals were randomly allocated to groups (4; each of 24 animals) and respiration chambers and typically 10 progeny per sire were randomly selected to be measured for CH4 emission. Only complete records were used and if a chamber seal was broken or less than 95% of the offered feed was eaten on the day of measurement then the record was discarded.

Figure 1 A photograph of a sheep in a metabolic crate, within the respiration chamber. The measurement protocol used for the initial evaluation is presented below. An adaptation period of typically 21 days was followed by measurements within the respiration chamber conducted over 2 days for round 1 (M1 and M2). This was in turn followed by ∼14 days of rest and then another 2-day round of measurements (M3 and M4).

For subsequent analysis CH4 emissions were expressed as 24-h total gross emissions (g CH4/day) and as CH4 yield (g CH4/kg DMI) per unit of ingested feed. LW (kg) was also measured on each measurement round. Additional performance information was downloaded from Sheep Improvement Limited (SIL), the New Zealand sheep genetic evaluation database, for the animals measured and their contemporaries. This was an attempt to make performance trait estimates more accurate and also allow unbiased estimates of maternal effects where these were relevant. Additional information included pedigree records from the five birth flocks of animals, born 1990 to 2011, and the following animal information: sex (male, female), birth rearing rank (Brr), age of dam (aod), birth day deviation (bdev) from the contemporary group (flock.birth year.sex, weaning weight (WWT) grazing mob) where “.” indicates an interaction. Production trait measurements included: weaning weight at 3 months (kg; WWT), LW at 6 or 8 months (kg; LW8), fleece weight at 12 months (kg; FW12), ultra sound eye muscle depth (mm; EMD), and dag score (faecal accumulation in the perineum region) at 3 or 8 months (DAG3, DAG8). Of these WWT, LW8, FW12 and EMD are standard production traits, whereas DAG3 and DAG8 are visually assessed traits commonly scored on a 6-point scale (0 no faecal accumulation to five faecal accumulation of the breech and down the legs).

The data collected were analysed in a mixed model using ASREML 3.0 (Gilmour et al., Reference Gilmour, Gogel, Cullis and Thompson2009). Both single trait and bivariate analyses were undertaken. The former were for traits measured as part of the respiration chamber measurements g CH4/day, g CH4/kg DMI and LW while the latter were for estimating correlations of production and visual traits with g CH4/day and g CH4/kg DMI. Initial exploratory analyses were undertaken using a general linear model procedure, fitting a repeatability model (SAS, 2005) for g CH4/day, g CH4/kg DMI and LW. Fixed effects fitted included flock (flk), birth year (byr), sex, birth rearing rank (brr), grazing mob (trait mob), recording year (ryr), round (1 to 3), lot (of 96 animals, 1 to 5), group (of up to 24 within year, 1 to 13), system (8 chambers to a system, 1 to 3), and chamber (1 to 24). Birthday deviation (bdev) and aod as linear and quadratic (aod2) were fitted as covariates. Interactions between these effects were tested and by a process of backwards elimination parsimonious models were selected (Table 1). For industry production traits standard fixed effects used by Sheep Improvement limited (www.sil.co.nz) were utilised (Pickering et al., Reference Pickering, Dodds, Blair, Hickson, Johnson and McEwan2011). For genetic estimates animal was fitted as a random effect with covariances proportional to the numerator relationship matrix along with permanent environmental effects (within round, between rounds and between years) where this was appropriate.

Table 1 Final mixed models and fixed effects used for individual trait analysis

1g CH4/day: methane (g/day); g CH4/kg DMI: methane/dry matter intake (g/kg); LW: live weight at measurement; WWT: weaning weight at 3 months; LW8: live weight at 8 months; FW12: fleece weight at 12 months; EMD: eye muscle depth; DAG3, DAG8: dag score at 3 and 8 months.

2brr: birth rearing rank; bdev: birth day deviation; flk: birth flock; ryr: recording year; lot: mob of 96 animals; group: sub-mob of up to 24 animals within a lot measured contemporaneously; round: measurement time 14 days apart; aod: age of dam as linear; aod2: age of dam as quadratic; yr: birth year; TRAITmob: trait grazing mob.

3eperm: permanent environmental effects.

Results and discussion

The final parsimonious models selected are described in Table 1. Chamber effects for CH4 emissions were investigated, found to be non-significant, and therefore removed from final models. For the trait g CH4/day gross emissions were influenced by LW (and associated feed offered) so factors that influenced these traits such as brr were significant. For the trait g CH4/kg DMI only fixed effects affecting contemporary group formation were significant, presumably reflecting intrinsic factors including age, diet variations and flock and group treatment effects.

In total, 5236 daily complete CH4 measurements were recorded (∼4.3 records/animal; Table 2). The heritability of gross CH4 emission was moderate with an estimate 0.29 ± 0.05 and the coefficient of variation was 12.9%; similar to that of LW. Given that CH4 emission is influenced by intake, which in this situation is dependent on LW, of more interest is the heritability of CH4 yield (g CH4/kg DMI) which had a heritability estimate of 0.13 ± 0.03 and a coefficient of variation of 10.3%. These estimates are for a single 24-h measurement. Of considerable interest in any breeding programme is the repeatability of the measurement over both short (adjacent days), medium (several weeks) and long term (years) as these allow investigation of the consequences of repeated measurements and the utility of measurements taken at one age or time at subsequent measurements. The results for gCH4/day show very high correlation between consecutive days, but the repeatability across rounds or across years is considerably lower at 0.53–0.55 compared to 0.80–0.88 for LW. This is perhaps not surprising, given that LW is a cumulative trait, whereas daily emissions are not. However, the results do suggest that a single g CH4/day measurement contains a considerable amount of error and that recording consecutive days does little to mitigate this. It also suggests that repeatability across time appears to be relatively stable after an initial separation period of at least 14 days and suggests that multiple measurements offers the potential to more accurately rank animals. Given the available estimates, it is impossible to directly compare these results with those of Garnsworthy et al. (Reference Garnsworthy, Craigon, Hernandez-Medrano and and Saunders2012), but indirectly they appear to be similar. Again, the results of Robinson et al. (Reference Robinson, Goopy, Hegarty and Vercoe2010 and Reference Robinson, Bickell, Toovey, Revell and Vercoe2011) also indicate that measurements on consecutive days seem to share a close relationship, presumably because relative to passage rate, feed eaten one day takes several days to be fully cleared from the rumen. It also suggests that selection at one age may well result in stable differences over an extended period of the animal's life. However, these observations are based on a small number of records derived from extreme animals and we would suggest caution until significantly more records have been collected and analysed. For the trait g CH4/kg DMI, the repeatability is also high when measured over consecutive days, but drops to a low but stable value when compared across rounds or years. This lower repeatability actually increases the benefit of measuring additional records in order to rank individuals. The estimate of heritability of 0.13 provided here for g CH4/kg DMI is also similar to that of Robinson et al. (Reference Robinson, Goopy, Hegarty and Vercoe2010) who reported an estimate of 0.30 for gross emission and 0.13 for LW adjusted emission, obtained from brief 1-h measurements, with corresponding repeatabilities of 0.47 and 0.32. The LW adjusted emission is not strictly comparable with our results as the work involved grazing animals and intake was not recorded.

Table 2 Heritability (h2), repeatability estimates (±s.e.) for methane traits and LW at measurement

LW = live weight; DMI = dry matter intake.

The phenotypic and genetic correlations with selected production traits up to 1 year of age along with the heritability of the production traits are presented in Table 3. The heritabilities of the production traits are broadly consistent with recent estimates from similar New Zealand dual purpose sheep (Pickering et al., Reference Pickering, Dodds, Blair, Hickson, Johnson and McEwan2011). In general, they are slightly higher, but that probably reflects the genetic diversity sampled in this analysis. For g CH4/day, the genetic correlations are often somewhat higher than the phenotypic correlations and generally reflect the indirect association between g CH4/day, intake and LW in this dataset. Therefore, of more importance are the genetic and phenotypic relationships with g CH4/kg DMI. With the exception of fleece weight, correlations were low and not significantly different from zero for the g CH4/kg DMI trait. For fleece weight the phenotypic and genetic correlation estimates were −0.08 ± 0.03 and −0.32 ± 0.11 suggesting a low economically favourable relationship that is, lower g CH4/kg DMI is associated with higher FW12.

Table 3 Estimates of SIL production trait heritabilities (h2) (±s.e.) and genetic (r g) and phenotypic (r p) correlations with methane traits

SIL = Sheep Improvement Limited; DMI = dry matter intake; WWT = weaning weight; LW = live weight; FW = fleece weight; EMD = eye muscle depth.

The results presented, comprehensively show that both gross CH4 (g CH4/day) and CH4 yield (g CH4/kg DMI) are heritable and repeatable traits. Although variation in intake accounts for a significant fraction of the phenotypic and genetic variation in CH4 emissions, there remains a component that is independent of intake and offers hope for genetic selection as a potential option to reduce CH4 yield emissions. On the basis of the limited results of Pinares-Patiño et al. (Reference Pinares-Patiño, Ebrahimi, McEwan, Clark and Luo2011a and Reference Pinares-Patiño, McEwan, Dodds, Cárdenas, Hegarty, Koolaard and Clark2011c), whose animals formed a part of this work, it would appear that these differences remain across a variety of diets and ages. These diets span the likely range to be encountered in temperate climates when grazing improved pastures or feedlot conditions. As previously identified by Janssen (Reference Janssen2010) in his review and also by Pinares-Patiño et al. (Reference Pinares-Patiño, Ulyatt, Lassey, Barry and Holmes2003 and Reference Pinares-Patiño, Ebrahimi, McEwan, Clark and Luo2011a): reduced CH4 emission is also associated with increased rumen flow rates.

There is at present no evidence from this work that selection for reduced CH4 yield is phenotypically or genetically associated with reduced productivity for any of the traits examined to date, albeit a wider range of traits and ages needs to be examined. This includes adult maternal traits which have major effects on farm scale CH4 emissions as well as productivity (Cottle and Connington, 2012; Ludemann et al., Reference Ludemann, Bryne, Sise and Amer2012). Until reliable estimates for these are available (estimated to be late 2014 for this experiment) updating modelling studies will be premature.

It is acknowledged that the current work suffers a weakness in that feed intake was controlled during CH4 emission measurement, which consisted of a brief period of around 4 days. However, productivity was measured almost exclusively at pasture where feeding levels varied with season from near maintenance to ad libitum. In addition, grazing pasture also allowed the animals to vary their individual intakes and chewing and rumination behaviour. Thus, a key research task is to validate that the CH4 differences observed in chambers are also present in animals when grazing pasture. Work is currently underway to examine this across seasons and feeding levels using both portable accumulation chambers (Goopy et al., Reference Goopy, Woodgate, Donaldson, Robinson and Hegarty2011) and using the SF6 tracer technique (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Huyler, Westberg, Lamb and Zimmerman1994; Pinares-Patiño et al., Reference Pinares-Patiño, Lassey, Martin, Molano, Fernandez, MacLean, Sandoval, Luo and Clark2011b). Another aspect worthy of investigation is measurement of voluntary feed intake and feed efficiency in these animals. It is perhaps unfortunate that worldwide investigations into CH4 emissions and feed efficiency have been undertaken largely independently of each other to date with only very limited contemporaneous measurement of both traits.

A further research priority is to confirm that similar relationships are present in beef and dairy cattle. The development and validation of the utility of brief measurements using ‘sniffers’ for cattle as reported by Garnsworthy et al. (Reference Garnsworthy, Craigon, Hernandez-Medrano and and Saunders2012) offers the potential that this can be done on a suitable scale to obtain useful genetic estimates. Finally, almost all of the work to date has been conducted in temperate climates using C3 grass, legume or grain diets; and there is an urgent need to assess whether these results have any relevance to tropically adapted ruminants grazing lower quality C4 pasture diets.

Divergent selection lines are being developed from the extremes of the animals identified in this research and the following research topics are underway or planned. Firstly, progeny from the divergent selection lines will continue to be measured using the current protocol and selection will be on the basis of breeding values for g CH4/kg DMI. For both the original screened animals and the selection lines detailed measurements of production traits will be undertaken including maternal traits such as milk production and composition, reproductive status and adult LW, condition score and wool production. The intention is to monitor all traits that currently contribute to New Zealand dual-purpose sheep selection indexes (http://www.sil.co.nz/) and to estimate their genetic correlations with the CH4 emission traits. Secondly, studies are underway using the selection lines and existing data to determine the opportunities for indirect selection or rapid measurements of CH4 emissions in order to rank animals. Finally, studies have commenced to examine what, if any, differences are present in the selection lines with regards to rumen anatomy, physiology and microbiology. This includes studies at different physiological ages, with different measurement techniques and for different diets.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by the Pastoral Greenhouse Gas Research Consortium, Sustainable Land Management and Climate Change and the New Zealand Agricultural Greenhouse Gas Research Centre. The animals themselves were part of the Ovita partnership and the related Central Progeny Test: both funded in part or whole by Beef+Lamb New Zealand. Thanks also to the Central Progeny Test collaborating organisations: AgResearch Woodlands especially Kevin Knowler, On Farm Research especially Paul Muir, Lincoln University especially Chris Logan and AbacusBio Ltd especially Neville Jopson. The New Zealand Government in support of the Livestock Research Group of the Global Research Alliance (GRA) on Agricultural Greenhouse Gases has funded Natalie Pickering's postdoctoral fellowship.

This paper was published as part of a supplement to animal, publication of which was supported by the Greenhouse Gases & Animal Agriculture Conference 2013. The papers included in this supplement were invited by the Guest Editors and have undergone the standard journal formal review process. They may be cited. The Guest Editors appointed to this supplement are R. J. Dewhurst, D. R. Chadwick, E. Charmley, N. M. Holden, D. A. Kenny, G. Lanigan, D. Moran, C. J. Newbold, P. O'Kiely, and T. Yan. The Guest Editors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary materials

For supplementary materials referred to in this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S1751731113000864