Introduction

The social acceptability of equestrian sport is at an all-time low. This was highlighted during the 2020 Olympic Games in Tokyo when there was global condemnation of an episode of horse abuse during the modern pentathlon. The incident led to the removal of the equestrian phase in that sport (Ingle Reference Ingle2021). Soon after, a book calling for all equestrian sport to be removed from the Olympic Games (Taylor Reference Taylor2022) was published. Also, after calls for many years for the race to be banned (Cardwell Reference Cardwell2017), the 2023 running of the Grand National steeplechase in the United Kingdom was disrupted by protestors concerned about horse welfare (Skelton Reference Skelton2023). In 2022, a horse welfare charity conducted a survey in the UK and found 40% of respondents (822/2057) supported the continued use of horses in sport only if their welfare is improved, and 20% of respondents did not support the use of horses in sport under any circumstances (World Horse Welfare 2022). A larger international survey conducted by the Federation Equestre Internationale (FEI) indicated around 72% (of 42,000 participants) had concerns about sport horse welfare (Heleski Reference Heleski2023). These events and data signal the growing public unease about ridden horse welfare that threatens the sport horse industry’s social licence to operate (SLO) (Douglas et al. Reference Douglas, Owers and Campbell2022; Heleski Reference Heleski2023), where SLO refers to the level of community acceptance of a company, an industry or a specific activity within an industry (Jijelava & Vanclay Reference Jijelava and Vanclay2017).

Community concerns notwithstanding, legal scholars and animal welfare scientists have long-held concerns for the welfare of sport horses. Sneed (Reference Sneed2014), for instance, argued that:

“Horse abuse is a very serious and widespread problem impacting equine competitions’ integrity and threatening the horses’ well-being” (p 274)

A full exposition of the welfare challenges faced by ridden horses is beyond the scope of this paper, however, it is useful to point out some pertinent examples. These include that ridden horses suffer high rates of oral lesions due to bits and the way riders use bits (Tuomola et al. Reference Tuomola, Mäki-Kihniä, Valros, Mykkänen and Kujala-Wirth2021); most horses exhibit hyperreactive behaviours, such as bucking, spooking and rearing, while ridden (Hockenhull & Creighton Reference Hockenhull and Creighton2013; Luke et al. Reference Luke and Smith2022b) with these behaviours likely signaling pain (Dyson et al. Reference Dyson, Berger, Ellis and Mullard2018), stress (Borstel et al. Reference Borstel, Visser and Hall2017) and/or confusion (McLean & Christensen Reference McLean and Christensen2017) indicating compromised welfare. Many owners are poor at detecting common ailments such as back soreness and/or lameness, resulting in many horses being ridden when they are unfit for riding (Buckley Reference Buckley2009; Greve & Dyson Reference Greve and Dyson2014). High rates of wastage (the premature destruction or retirement of horses) are found in the racing industry where it is estimated 33% of racehorses are ‘wasted’ (killed) each year (Thomson et al. Reference Thomson, Hayek, Jones, Evans and McGreevy2014). Other welfare challenges include owners misinterpreting pain/stress/fear behaviour in horses (Rogers & Bell Reference Rogers and Bell2022), as well as misunderstanding horses’ nutritional needs (Furtado et al. Reference Furtado, Perkins, Pinchbeck, McGowan, Watkins and Christley2020), housing needs (Hockenhull & Furtado Reference Hockenhull and Furtado2021) and delaying euthanasia (Horseman Reference Horseman2017; Bell & Rogers Reference Bell and Rogers2021).

Concerns about animal welfare in other animal-use industries have seen governments step in and ban such activities or severely regulate their operation. In Australia, jumps horse racing is banned in all states except Victoria (MacLennan Reference MacLennan2022), the export of live cattle was prohibited in 2011 (Schoenmaker & Alexander Reference Schoenmaker and Alexander2012), although has subsequently been reinstated, and greyhound racing was banned for a period in 2017 (Markwell et al. Reference Markwell, Firth and Hing2017). It has been suggested if the sport horse industry is to have a long-term future, it must transform from “an economically driven business and management model to a welfare-driven model” (Bergmann Reference Bergmann2015; p 495). Some equestrian organisations have responded to this growing threat to their social licence to operate by developing initiatives to promote horse welfare. For example, Pony Club Australia released a comprehensive horse welfare policy (Pony Club Australia 2023) and the Federation Equestre Internationale created an Equine Welfare and Ethics Commission to guide FEI horse welfare improvement initiatives (Equine Ethics and Wellbeing Commission 2023).

Strategies such as developing an evidence-based welfare policy and an advisory panel of experts appear to be rational organisational responses to a social licence under threat. However, it is too early to determine if these initiatives will deliver meaningful improvements in horse welfare. One factor that will strongly influence the success or otherwise of these initiatives is the degree to which the conceptualisation of horse welfare underpinning them aligns with society’s expectations regarding the ethical use of animals in sport. Unlike most scientific disciplines, animal welfare has essentially two components: aspects that pertain to the animal (such as the animal’s health, nutrition and mental state) which can be more or less studied scientifically, and the scientist’s values pertaining to what is better or worse for animals (Fraser et al. Reference Fraser, Weary, Pajor and Milligan1997). The dual challenge of what constitutes a scientifically robust approach for measuring animal welfare and the value-laden assumptions of what is better or worse for an animal means the concept of animal welfare is contested among scientists (Sainsbury Reference Sainsbury1986; Singer Reference Singer1996; Fraser et al. Reference Fraser, Weary, Pajor and Milligan1997; Rollin Reference Rollin2016).

With such disagreement among scientists, it is likely the equestrian community has a similarly fragmented understanding of horse welfare.

Research on equestrians’ conceptualisation of horse welfare is relatively limited. Among show horse exhibitors in the United States, physical attributes of the horse were deemed a more appropriate measure of welfare than behavioural measures or mental state (Voigt et al. Reference Voigt, Hiney, Richardson, Waite, Borron and Brady2016). A study of racing industry insiders developed and ranked 24 welfare priorities for racehorses (Mactaggart et al. Reference Mactaggart, Waran and Phillips2021). Horsemanship (understanding of horse behaviour and training) was ranked first, however, the experts determined training equipment, such as whips and tongue ties, “were not sufficiently important for welfare to be included in their Thoroughbred Racehorse Welfare Index” (Mactaggart & Phillips Reference Mactaggart and Phillips2023; p 26). Excluding painful equipment such as whips and tongue ties suggests racing stakeholders’ understanding of ‘horsemanship’ relates to a handler’s or rider’s efficiency and efficacy in producing horse behaviour required by the industry, rather than their ability to interact with the horse in a way that protects horse welfare. According to the Five Domains Model, using aversive and/or painful equipment such as whips (McGreevy et al. Reference McGreevy, Corken, Salvin and Black2012a) and tongue ties (Barton et al. Reference Barton, Lindenberg, Einspanier, Merle and Gehlen2022) will significantly diminish horse welfare. Failure to consider the negative affective aspects of painful equipment coupled with stakeholders high ranking of health and disease implies a utilitarian conceptualisation of horse welfare based largely on biological functioning. Similar results have been reported from studies of equestrian sports other than racing, such as dressage, showjumping and eventing. These studies found owners (Horseman et al. Reference Horseman, Buller, Mullan, Knowles, Barr and Whay2017; Furtado et al. Reference Furtado, Preshaw, Hockenhull, Wathan, Douglas, Horseman, Smith, Pollard, Pinchbeck, Rogers and Hall2021) and industry experts (DuBois et al. Reference DuBois, Hambly-Odame, Haley and Merkies2017) focused on horses’ physical health, while largely overlooking their mental health. Several authors have reported an anthropomorphic understanding of horse needs among horse owners. Horseman (Reference Horseman2017) found some owners feel horses are not ‘safe’ when in a paddock, where they may be exposed to such phenomena as bad weather and toxic plants. More recently, a study found horse owners may construct horse needs in terms of human preferences such as equating stables to a bedroom that keeps the horse comfortable and safe, and rugs as ‘pyjamas’ that keep the horse warm (Hockenhull & Furtado Reference Hockenhull and Furtado2021; p 2). It is interesting that even when owners use a very anthropomorphic approach to horse welfare, they continue to focus largely on their horse’s physical health and/or environment, while overlooking their psychological needs. Goodwin (Reference Goodwin and Waran2002), for example, argues that horses are physically and mentally adapted to life on an open plain or mountain, yet, as mentioned, equestrians do not appear to consider the welfare implications of failing to meet these important psychological needs.

While some studies have sought to explore equestrians’ understanding of horse welfare and how this affects horse welfare (Horseman et al. Reference Horseman, Buller, Mullan, Knowles, Barr and Whay2017; DuBois et al. Reference DuBois, Hambly-Odame, Haley and Merkies2018; Furtado et al. Reference Furtado, Preshaw, Hockenhull, Wathan, Douglas, Horseman, Smith, Pollard, Pinchbeck, Rogers and Hall2021) none have been identified that examined equestrians’ understanding of horse welfare in relation to the Five Domains Model (a discussion of the Five Domains Model follows). Moreover, in studying animal welfare, most scientists have used traditional reductionist approaches (Fraser Reference Fraser2009), yet approaches such as systems thinking may be more suited to exploring the complex problem of ridden horse welfare (Luke et al. Reference Luke, Rawluk and McAdie2022a). This study is likely the first to explore how horse welfare is conceived among a group of amateur equestrians using the Five Domains Model and systems thinking as its theoretical framework. The research was guided by the following research questions. First, to what extent does amateur equestrians’ understanding of ridden horse welfare align with the Five Domains Model? And, second, how do amateur equestrians perceive ridden horse welfare?

Theoretical framework

Systems thinking

In contrast to traditional reductionist approaches, systems thinking assumes, among other things, that systems are dynamic and irreducible, thinking is non-linear, and processes rather than objects are the subject of study (Capra & Luisi Reference Capra and Luisi2014). One of the hallmarks of a systems thinking approach is that systems are mapped, allowing for multiple perspectives to be appreciated, and in studying multiple perspectives, multiple conceptual frameworks or epistemologies may be needed (Bawden Reference Bawden1991; Houghton Reference Houghton2009). While the frameworks themselves may be unrelated or even contradictory, they are united by their relationship to the problem being studied. Leveraging the systems approach of multiple epistemologies is known as ‘systemic epistemology’ (Bateson Reference Bateson1987; Bawden Reference Bawden1991; Houghton Reference Houghton2009). It is through appreciating various perspectives, and using various epistemologies that systems thinking can deliver rich insights and novel solutions to complex problems.

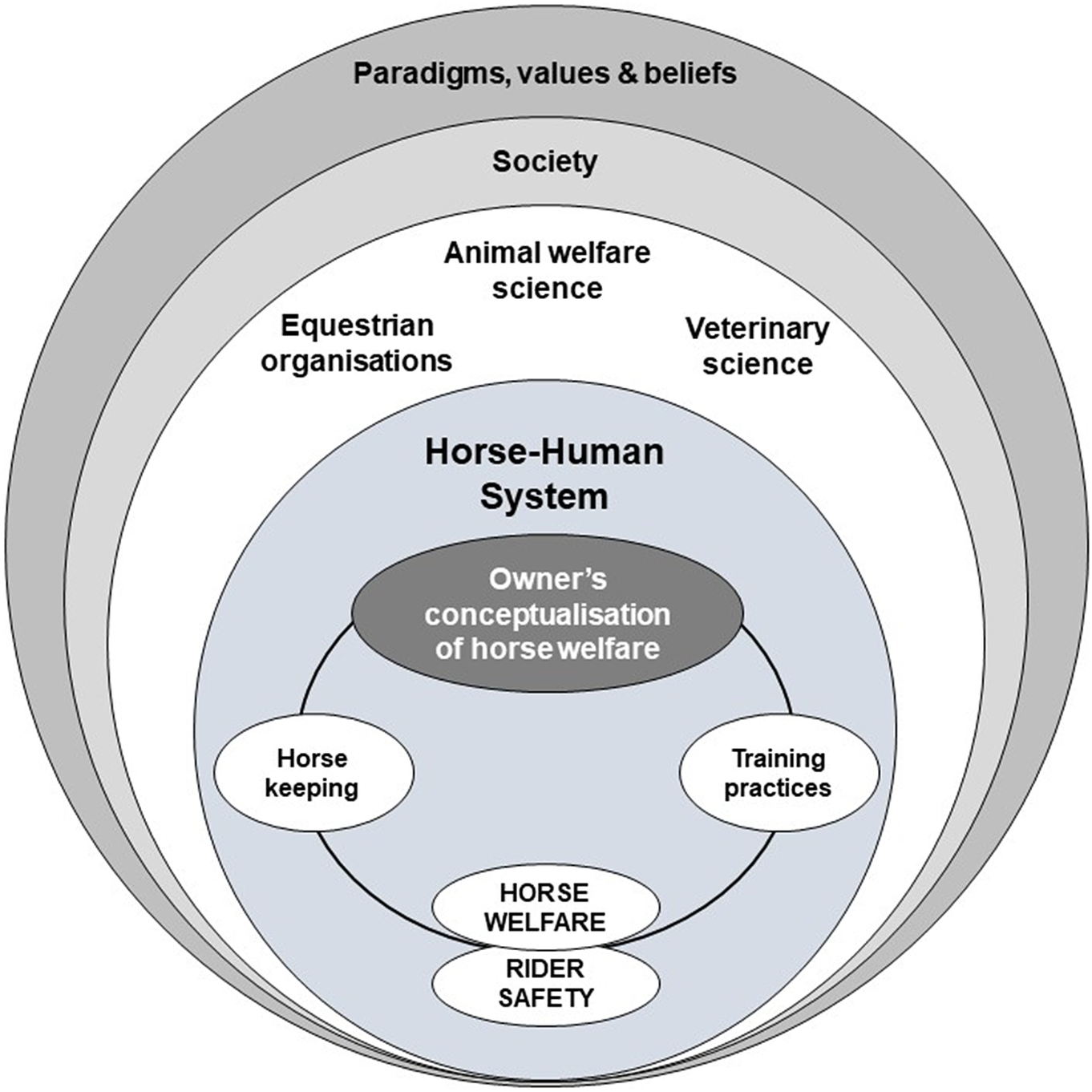

The challenge of ridden horse welfare has been examined from various vantage points including riders’ understanding of horse training (Warren-Smith & McGreevy Reference Warren-Smith and McGreevy2008; Brown & Connor Reference Brown and Connor2017; Luke et al. Reference Luke, McAdie, Warren-Smith, Rawluk and Smith2023), horse-keeping practices (Visser & Van Wijk-Jansen Reference Visser and Van Wijk-Jansen2012; Hockenhull & Creighton Reference Hockenhull and Creighton2013; Hanis et al. Reference Hanis, Chung, Kamalludin and Idrus2020), riding equipment (McGreevy et al. Reference McGreevy, Warren-Smith and Guisard2012b; Cook & Kibler Reference Cook and Kibler2019; Condon et al. Reference Condon, McGreevy, McLean, Williams and Randle2021; Tuomola et al. Reference Tuomola, Mäki-Kihniä, Valros, Mykkänen and Kujala-Wirth2021) and training practices (Borstel et al. Reference Borstel, Duncan, Shoveller, Merkies, Keeling and Millman2009; Lesimple et al. Reference Lesimple, Fureix, Menguy and Hausberger2010; Fenner et al. Reference Fenner, McLean and McGreevy2019). Most of this research examines these issues from the perspective of the individual equestrian. However, Figure 1 demonstrates that individual equestrians and horses (who in this study will be viewed as an irreducible horse-human system) act within larger systems such as equestrian organisations and society, which in turn are influenced by often unarticulated assumptions and beliefs (Bronfenbrenner Reference Bronfenbrenner1979; Capra & Luisi Reference Capra and Luisi2014).

Figure 1. Schematic situating individual horse-human systems within larger systems, including equestrian organisations and society. Mapping systems in this way can offer insights into unrecognised relationships and potential leverage points to facilitate positive change.

There is growing recognition that strategies focusing on individuals tend to deliver, at best, limited, short-term change, which ultimately serves to maintain the status quo (Prilleltensky Reference Prilleltensky1989; Shove Reference Shove2010; Delon Reference Delon2018). While investigating at the level of individual horse owners and their horses, it is hoped the adoption of an overarching wide-angle view provided by systems thinking will mean this study is well placed to take advantage of findings at the individual level and to leverage the system at various levels to improve horse welfare.

The Five Domains Model

It is widely accepted that the welfare of a ridden horse is dependent on those who provide the horse’s care and training (Hemsworth et al. Reference Hemsworth, Jongman and Coleman2015). How horse owners conceptualise and perceive horse welfare is likely to influence the care and training they provide (Kauppinen et al. Reference Kauppinen, Vainio, Valros, Rita and Vesala2010). Studies have examined horse owners’ attitudes (Hemsworth et al. Reference Hemsworth, Jongman and Coleman2015), perceptions (Collins et al. Reference Collins, Hanlon, More, Wall, Kennedy and Duggan2010; DuBois et al. Reference DuBois, Hambly-Odame, Haley and Merkies2017; Furtado et al. Reference Furtado, Preshaw, Hockenhull, Wathan, Douglas, Horseman, Smith, Pollard, Pinchbeck, Rogers and Hall2021) and understanding (Horseman et al. Reference Horseman, Buller, Mullan, Knowles, Barr and Whay2017; Smith et al. Reference Smith, Furtado, Brigden, Pinchbeck and Perkins2022) of horse welfare in the last 15 years, but in many respects, this is an under-researched topic (Hemsworth et al. Reference Hemsworth, Jongman and Coleman2015).

Since the second half of the 20th century, the science of animal welfare has seen much progress in terms of how animal welfare is conceptualised (Mellor & Burns Reference Mellor and Burns2020). Although, the progress in improving animals’ lives is perhaps less advanced. Broadly, concerns for animal welfare have tended to focus on three distinct approaches: quality of life, which is often built around the notion of an animal being free to live a ‘natural’ life; affective experiences, such that an animal is free from suffering, pain, hunger or other negative affective states; and the third approach, often adopted by farmers and veterinarians, focuses on the biological functioning of animals such that the provision of shelter, nutrition and healthcare equates to good animal welfare (Fraser et al. Reference Fraser, Weary, Pajor and Milligan1997). Recently, the development of the Five Domains Model (Mellor et al. Reference Mellor, Beausoleil, Littlewood, McLean, McGreevy, Jones and Wilkins2020) sees these three approaches integrated and evolved so that animal welfare is constructed as a dynamic system that includes each of the three elements described above. Nutrition, environment, physical health and behavioural interactions (including interactions with both human and non-human animals) comprise the first four domains which subsequently feed into the fifth domain, that of animal mental state or affect (Mellor et al. Reference Mellor, Beausoleil, Littlewood, McLean, McGreevy, Jones and Wilkins2020). The Five Domains Model will be used as the scientific conceptualisation of horse welfare in this study.

Materials and methods

Ethical approval

This research project received ethics approval from Central Queensland University Human Ethics Committee, approval number, 0000023272.

Data collection and analysis

Participants were interviewed using a semi-structured format. Interviews were conducted by the first author (KL) throughout 2022 at the participants’ home or horse agistment facility. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed and data were managed using NVivo software, version 1.6.1.

The interviews were divided into three sections. In the first section participants were invited to share how they care for and train their horse. The second component of the interview asked several broad questions about their choice of riding equipment, the challenges they face as riders and horse owners, and their opinion on ridden horse welfare. The third aspect of the interview focused on four hypothetical vignettes depicting commonly encountered scenarios such as the appropriate age for the horse to begin foundation training, how to manage a tense or unresponsive horse while riding, and how to manage a horse that is difficult to catch (see Supplementary material).

Transcripts were thematically analysed following Braun and Clarke’s (Reference Braun and Clarke2006) six-phase process. Thematic analysis is not a singular approach. As such, an iterative, reflexive approach informed by social constructionism (Braun & Clarke Reference Braun and Clarke2013) was used, and data were examined from a critical realist perspective (Moon & Blackman Reference Moon and Blackman2014). The researcher takes an active role in data coding to identify patterns and themes, and the researcher brings to this process their own theoretical positions and values (Braun & Clark Reference Braun and Clarke2006). In this study the researcher adopted an equine-centric position regarding data analysis, and in keeping with the Five Domains Model, horse mental state was prioritised above all other considerations when coding and analysing the data.

The coding process involved reading transcripts twice to become familiar with the data. Each transcript was then inductively coded in relation to the two research questions. The transcripts and codes were then reviewed once more using the Five Domains Model as a guide. Applying the Five Domains Model lens facilitated the identification of new codes and the refinement of some existing codes. This was an iterative, non-linear process (Braun & Clarke Reference Braun and Clarke2019). Codes were then reviewed and, where appropriate, grouped to form major codes. Throughout this process themes were developed and refined, with three themes identified. Thus far, the analysis interrogated the data from an individual perspective. The final analysis however, incorporated systems thinking and examined the themes in relation to systems beyond the individual, such as equestrian organisations, veterinarians, and the general public (see Figure 1).

It should be noted that analysing the data in the manner described above highlights where participants’ perception and a scientist’s perception align and diverge. Identification and discussion of emergent themes is not intended to be critical of participants, but to highlight that horse-human interactions can be understood from different perspectives. Sharing alternative perspectives can sometimes lead to novel ways of seeing (Meadows Reference Meadows1999) and facilitate new solutions to old problems.

Participant recruitment and response

Recreational sport horse riders residing in Victoria, Australia were targeted via social media posts (Facebook). Non-paid advertisements (posts) were placed in various Facebook interest groups, including activity-specific groups such as campdrafting, dressage, eventing, showing, showjumping, and reining groups and organisation groups such as the Horse Riding Clubs Association of Victoria (HRCAV) unofficial group (Pickering & Hockenhull Reference Pickering and Hockenhull2019; Gasteiger et al. Reference Gasteiger, Vedhara, Massey, Jia, Ayling, Chalder, Coupland and Broadbent2021). Interested participants were directed to a brief screening survey to ensure they met inclusion criteria, which were: that they resided in Victoria, Australia; owned or were responsible for the care of at least one horse; and that they rode their horse at least once a week. Participants who met these criteria were invited to leave their contact details and were contacted by the first author (KL) who arranged an interview time and location that was convenient for the participant. All participants volunteered and provided informed consent electronically and verbally at the time of the study session. Efforts were made to recruit a diverse sample that included riders from a range of equestrian disciplines, male and female riders with a wide range of ages and locations (metropolitan, semi-rural and rural) across Victoria. To protect anonymity of responses, all participants are referred to according to an assigned identifier, P1 through to P19.

Participant demographics

As a qualitative study, the goal was to obtain a depth of understanding rather than generalisable results, therefore achieving a representative sample of the equestrian population was not the goal. However, the sample covered a broad range of ages, from 19 to 70, and included horse owners from metropolitan, semi-rural and rural Victoria. At the grassroots level, equestrian sport is female dominated, and this was reflected in the sample, with 17 female and two male participants. Many participants engaged in dressage, however there were also participants whose primary focus was eventing, showjumping and trail riding. Participants were given a set of criteria and asked to self-assess their level of competency (beginner – less than 60 h of lessons and/or still working on balance at canter; novice – over 60 h of lessons and feel balanced at canter; intermediate – over 200 h of lessons and/or competition experience and/or extensive other riding and have ridden green/inexperienced horses; advanced – competing/training at an advanced level and/or started young horses and/or extensive experience training green/inexperienced horses; or professional).

Results and discussion

Good horse welfare is tangible

Participants were keen to demonstrate horse welfare was a high priority and highlight the sacrifices they often made to provide high quality horse care. More than once, a participant joked that their horse received regular professional attention such as myotherapy or chiropractic care, when such care for the owner was not an option. For most participants, good horse care and good horse welfare were interchangeable. Horse welfare was often constructed as something tangible that could be seen in examples such as freshly laundered cotton rugs, quality feed that was fed at the same time each day, the provision of good dental care and well-fitted, high-quality equipment.

They’ve got two [saddle cloths]. So, one’s in the wash and one dry. I have a drying rack over there, so even if it’s wet, I can pop them on the drying rack. Yeah, with their rugs, so the rugs are all changed once a week and washed and ready to go back on them at the end of the week. Yeah, so that’s good, and they all have show sets as well. [P7, female, advanced show rider].

Another participant put it like this:

I think the majority of horse owners who are doing it for the love of horses, which is lots of people, their horses are happy and well-fed and are trimmed, not cold. I think that’s good enough and they’ve got shelter, water, food. They’re happy. [P19, female rider, intermediate eventer].

The focus on the physical aspects of horse welfare was also seen among participants competing at a relatively high level of amateur competition, such as a 3* eventing rider who was interviewed. When asked about the biggest welfare issues among horses in her sport she responded:

Not having enough forage, you know, land is kind of hard to acquire these days and people… they’re just trying to keep as many horses on the land to earn more money through agistment and stuff like that, but then they don’t care for grass and grass is a big part of their diet. [P12, female, advanced event rider].

This way of viewing horse welfare is consistent with how many veterinarians and farmers construct welfare in terms of the biological functioning of the animal (Fraser et al. Reference Fraser, Weary, Pajor and Milligan1997). Also, similar results have been reported from studies in other regions such as the US (Voigt et al. Reference Voigt, Hiney, Richardson, Waite, Borron and Brady2016), the UK (Furtado et al. Reference Furtado, Preshaw, Hockenhull, Wathan, Douglas, Horseman, Smith, Pollard, Pinchbeck, Rogers and Hall2021) and Canada (DuBois et al. Reference DuBois, Hambly-Odame, Haley and Merkies2017). Although the above quotation mentions horses are ‘happy’, it appears to be more a statement of logical reasoning such that if horses’ biological needs are met, then it follows they are happy, rather than the participant critically reflecting upon the affective state of her horses.

Our finding that equestrians’ construction of horse welfare focuses on horses’ physical health aligns closely with the well-known Five Freedoms approach to animal welfare (Mellor Reference Mellor2016). The Five Freedoms approach offers a broadly anthropocentric understanding of animal welfare by focusing on human actions to ensure animals are ‘free from’ or ‘as free as possible from’ negative experiences such as thirst or hunger, rather than on the animal’s subjective experience per se. The more contemporary Five Domains Model emphasises good animal welfare ultimately rests on an animal’s mental state. Therefore, meeting an animal’s physical needs is necessary for good welfare, but not sufficient, because it overlooks the primary determinant of welfare, which is the animal’s mental state. This distinction is especially important for ridden horses, who are likely to have their physical needs met (because physical health is closely related to athletic performance) (Bolwell et al. Reference Bolwell, Rogers, French and Firth2013; Araneda Reference Araneda2022), yet may experience a poor mental state, due to owners neglecting or overlooking this aspect of their welfare (Horseman Reference Horseman2017).

The following example illustrates how horses can receive excellent physical care yet have a poor mental state due to poor training. It also highlights why horse welfare is particularly vulnerable during riding. The Five Domains Model stresses the importance of animal agency as a contributor to positive affective states and, thus, good welfare (Mellor et al. Reference Mellor, Beausoleil, Littlewood, McLean, McGreevy, Jones and Wilkins2020). During riding, especially in sports such as dressage that require the rider to dictate in very fine detail often via extensive use of aversive stimuli, where the horse travels, how fast they travel, and their posture while traveling, it is difficult to imagine the horse possessing a sense of agency during these interactions. However, the effect of riding on horses’ agency was not raised by any participants as a potential welfare issue. Horses’ behavioural flexibility and tolerance of human intervention make them vulnerable to welfare insults (McGreevy et al. Reference McGreevy, McLean, Buckley, McConaghy and McLean2011). Equestrians’ apparent lack of recognition of the extent to which horses’ agency might be compromised during riding likely increases this vulnerability. Visser and Van Wijk-Jansen (Reference Visser and Van Wijk-Jansen2012) stressed the importance of conceptual knowledge in building equestrians’ capacity to enhance horse welfare, therefore identifying a gap between equestrians’ current conceptualisation of welfare and the Five Domains Model emphasises the need for programmes that address these conceptual deficits.

Owners often misinterpret unwanted horse behaviour

Based on the Five Domains Model, animal welfare resides within the horses’ subjective experience of their life, which is reflected in their affective or mental state (Mellor & Burns Reference Mellor and Burns2020). It is generally accepted that some understanding of an animal’s mental state can be determined by their behaviour (Dawkins Reference Dawkins2003; Lee et al. Reference Lee, Floyd, Erb and Houpt2011; Bornmann et al. Reference Bornmann, Randle and Williams2021) and some widely accepted behavioural indicators of horse welfare have been developed (Lesimple Reference Lesimple2020). These include stereotypies (Tadich et al. Reference Tadich, Weber and Nicol2013), rearing (McLean & Christensen Reference McLean and Christensen2017; Dyson et al. Reference Dyson, Berger, Ellis and Mullard2018) and aggression (Fureix et al. Reference Fureix, Menguy and Hausberger2010). These behaviours are typically deemed ‘problematic’ by many horse owners and horses are often punished for performing these behaviours (Jonckheer-Sheehy et al. Reference Jonckheer-Sheehy, Delesalle, van den Belt and van den Boom2012). We identified a theme whereby unwanted behaviours deemed annoying or problematic by an owner, such as routinely showing aggression towards people, were either dismissed and/or punished and often attributed to a character flaw of the horse. An example of this theme can be seen below, where a highly experienced horseperson, who regularly fulfilled the role of coach and dressage judge in her local community, described the behaviour of her horse:

He [the horse] snoots. You know, ears back and juts out his… flares his nostrils at everybody. But yet, there’s no reason. Like he’s never been… oh, he’ll get a whack if he’s naughty, but he’s never been mistreated. Yeah, like he hasn’t been tied or flogged or dropped or, you know, some things you hear what people do. Yet it’s just… everything’s just so sad. Everyone’s against me type attitude [from the horse]. [P6, female, advanced dressage rider and judge].

In this quote, Participant 6 is describing her horse who is aggressive and could be in pain (ears back, flared nostrils, will bite when groomed) (Fureix et al. Reference Fureix, Menguy and Hausberger2010; Gleerup et al. Reference Gleerup, Forkman, Lindegaard and Andersen2015). Yet her assessment of his behaviour was the horse was malingering and had an attitude problem. Misinterpretation of horse behaviour is relatively common among horse owners (Bell et al. Reference Rogers, Taylor and Busby2019) and behaviour such as aggression tends not to be interpreted as a welfare problem. Earlier, we reported participants generally understood welfare in terms of good physical health and providing what the horse needs, so they have good health (which aligns with the Five Freedoms). Understood in this way, it is unsurprising, P6 held no concerns for her horse’s welfare because she was a knowledgeable horse owner who provided good food and healthcare for her horse and used quality, well-fitting equipment. With all of her horse’s needs met in this way, it follows his aggression and sadness must be due to a deficit in the horse. However, using a different framework, such as the Five Domains Model to understand her horse’s behaviour, his aggression and sadness would be attributed to some aspect of his care or training, or some physical problem that has not yet been identified.

In another example, a participant described their horse as regularly bolting, a hyperreactive behaviour often signaling poor mental state (McLean & Christensen Reference McLean and Christensen2017) and/or pain (Dyson et al. Reference Dyson, Berger, Ellis and Mullard2018), however, the owner interpreted the behaviour as a trait of the horse, describing the horse as ‘hot’ and in need of more training (even though the horse was 24 years old and had competed at a high level).

The first time I took him out, we actually got a warning from the local policeman, because the policeman clocked us doing 47 kph in a 40 kph zone. Yeah. Not intentionally. It was not long after I had him. On the way out he was fine, but I didn’t realise he runs home in a big way and so we turned for home and he just took off. [P9, male, beginner rider].

The horse’s owner (P9) described several scenarios when his horse bolted: while showjumping, out on cross country, and while trail riding around his property. His horse was a thoroughbred that had raced and had a second career as a high-level eventer. The owner attributed the uncontrollable running and bolting to the horse being an enthusiastic, hot horse who knows ‘his job.’ As with the previous participant, P9 did not suggest he was concerned (or that his very experienced trainer was concerned) that his horse’s behaviour might reflect a welfare issue.

More subtle behaviour is also overlooked and/or misinterpreted. An advanced level female dressage rider described her pony’s canter and character in this way:

His canter was good, but it went funny. [He] gets a bit lazy now, so he needs to pick up his canter at the back and carry himself from the back. [P4, female, advanced dressage rider].

She (P4) goes on to describe how the pony has ‘trouble’ staying ‘round.’ Dressage riders often aspire to attain a desirable posture referred to as ‘round’ or ‘in a frame’ while riding their horse. This posture is usually achieved through the simultaneous use of strong bit pressure (deceleration cue) and strong leg pressure (acceleration cue). The simultaneous use of conflicting cues is considered contrary to accepted training principles and a horse welfare issue (Podhajsky Reference Podhajsky1967; McLean & McGreevy Reference McLean and McGreevy2010b).

He does have trouble coming round. It’s the neck shape. It’s the shape of him. Yeah, I mean, it’s not just me having trouble, my daughter has trouble, you know, he has trouble keeping round. [P4, female, advanced dressage rider].

Her (P4) solution to this problem was to use a double bridle because when ridden in a double bridle, the pony “just does travel better.” What the participant meant by travelling better was the pony tucked his nose in towards his chest (i.e. became ‘round’). While it is unlikely the owner would knowingly be unkind to her pony, the change in her pony’s posture when ridden in a double bridle is likely to be in response to more intense pressure/pain from the addition of a second bit in his mouth that uses leverage and a curb chain (McGreevy et al. Reference McGreevy, Warren-Smith and Guisard2012b).

All of the participants in this study prioritised their horse’s welfare and demonstrated this by providing good nutrition and healthcare for their horses. They were eager to demonstrate this and gave examples of practices they adopted to ensure their horses had good welfare. However, constructing horse welfare in terms of biological functioning and need provision can create a welfare blind spot. In a review of mouth pain in horses, the term ‘bit blindness’ was coined (Mellor Reference Mellor2020; p 1). Participants in the current study were diligent in providing quality nutrition and healthcare for their horses, and used well-fitting equipment, so according to their definition, their horses had good welfare. This was particularly apparent in the quote above from P4. Participant 4 was fastidious about ensuring her horse’s physical needs were met. Based on this she assumed he was sound and should be able to perform as she required. It also meant when the pony did not perform as expected, the problem was judged to be intrinsic to the pony. He was malingering or the ‘wrong shape.’ There was no suggestion from P4 that she had considered the possibility that what was being asked of the pony might be physically difficult, uncomfortable or confusing. Many participants used a similar approach to interpreting horse behaviour, which is consistent with others’ work examining horse owners (Jonckheer-Sheehy et al. Reference Jonckheer-Sheehy, Delesalle, van den Belt and van den Boom2012; Horseman et al. Reference Horseman, Buller, Mullan, Knowles, Barr and Whay2017; Story et al. Reference Story, Nout-Lomas, Aboellail, Selberg, Barrett, Mcllwraith and Haussler2021) and equine professionals (Mansmann et al. Reference Mansmann, Currie, Correa, Sherman and vom Orde2011; Pearson et al. Reference Pearson, Reardon, Keen and Waran2020) similarly misinterpreting ‘problem’ horse behaviour.

Although participants generally focused on biological functioning and did not link ‘problem’ horse behaviour to welfare, a subtle unease could be observed among nearly all participants, a sense that on some level they recognised horse welfare, especially when horses are ridden, is perhaps not as good as publicly portrayed. Most commonly this disquiet was observed towards the end of the interview, and often after the recorder had been turned off.

Equestrians publicly minimise horse welfare but are privately concerned

Interviews generally began by asking participants to give an overview of their life with horses, followed by a series of questions. One question asked participants directly about their thoughts on ridden horse welfare. There was a spectrum of responses, from participants believing no problems existed to those suggesting there are practices in equestrian sport that seriously compromise horse welfare. There was also a spectrum in participants’ level of comfort and willingness to engage with this question. Either at this point in the interview, or at the end, many participants checked their responses would be anonymous. The consistent nature of participants’ fear of being identified as someone who was disclosing horse welfare issues within the industry, highlighted a tension between what equestrians share publicly (that horse welfare is equestrians’ highest priority and sport horse welfare is good) and their privately held beliefs. In addition to the inconsistency between public and private thoughts, participants also sought to distance themselves from ‘typical equestrians’, checking if the interviewer felt that their horse’s welfare was exemplary. This theme will now be explored.

As mentioned, participants differed in their concerns about horse welfare. Some participants were genuinely surprised to be asked this question, and felt (at least in their sport), no welfare issues existed.

My exposure to the horse welfare side of everything when ridden it’s not that bad I don’t think. And I know the eventing and dressage and showjumping side of it, all English things are OK. I don’t see a massive problem. [P19, female, intermediate eventing rider].

An older, more experienced horse owner was similarly nonplussed when asked about horse welfare, citing a commonly used argument, that horses are so large if they did not wish to participate in equestrian sport then an owner could not force them to do so:

I don’t know how you can make a 500 to 700 kilo horse do something it doesn’t want to do. Because if they don’t want to do it, they won’t do it. [P6, female, advanced dressage rider].

Another participant, talking about horses competing at an elite level phrased it like this:

You’d have to be really treating that horse poorly for it to perform at that level and it [the horse] not wanting to be there. [P17, female, intermediate dressage rider].

These views and arguments are broadly consistent with those put forward by many in the industry, including equestrian organisations, to positively shape the public discourse around horse welfare in equestrian sport (Racing Australia 2022; Federation Equestre Internationale 2023). Another common argument is that horses who are stabled, rugged and receive high quality food and healthcare ‘live like kings’ (Scheinman Reference Scheinman2015). Although one participant demonstrated there is more to this argument than is usually shared publicly. She put it like this:

And you can’t say that they’re not fed well. They’re beautifully fed. They’re beautifully rugged. They have the best vets, the best chiropractors, the best acupuncturists, the best farriers. But still, there’s that element that pushes them so hard that they’ll only last two seasons. [P8, female, advanced show rider].

This quote is important because it combines two distinct approaches participants used when discussing their horse welfare concerns. Some participants stressed concerns for horse welfare in sports other than their own sport; we will deem this the ‘other sport’ approach. Other participants focused on individuals at the extreme of their sport. For example, P2 stated “there are people that just shouldn’t own horses”, another participant stressed people see “that tiny percentage [doing the wrong thing] and they base the whole industry off that” (P12); we will deem this the ‘other people’ approach.

After assurances of anonymity, most riders expressed some concern for sport horse welfare. Often, when asked directly about ridden horse welfare, participants talked about ‘neglect’ and ‘abuse’, and as mentioned, several expressed the sentiment “there are people that just shouldn’t own horses” (P2). An intermediate dressage and former showjumping rider put it slightly differently and spoke about horses who needed rescuing from neglectful owners:

I mean, clearly, there’s a lot of horses still that are badly treated and left in paddocks and need rescuing and stuff… which is a downside. [P5, female, intermediate dressage rider].

Those competing at the highest level often shared first-hand experiences. A participant competing in high-level showing described competitors drugging their horses at local showing competitions, which she felt led to them taking extreme measures (as an alternative to drugging) when they were at large competitions where horses were more likely to be drug-tested.

You go to a Royal Show, and you can always pick ‘em… six hours on the lunge, seven hours on the lunge, overnight, [the horse] not allowed to lie down. Not watered. All to bring on fatigue so they can get in the ring for 20 minutes the next day and win. That concerns me. [P7, female, advanced show rider].

The same participant (P7) described competitors employing veterinarians to cut the nerves in their horse’s tail, so the horse can no longer swish or swing their tail. Tail swishing or swinging is undesirable for a show horse and would diminish a competitor’s chance of winning. Importantly, tail swishing during riding has been associated with musculoskeletal pain (Dyson et al. Reference Dyson, Berger, Ellis and Mullard2018) and/or conflict with the rider’s aids (Kienapfel et al. Reference Kienapfel, Link and Borstel2014; Górecka-Bruzda et al. Reference Górecka-Bruzda, Kosińska, Jaworski, Jezierski and Murphy2015), likely signaling some degree of negative affective state and therefore diminished welfare. Of course, the horse’s welfare outside of riding would also be negatively affected by this practice because the horse would be unable to swish their tail for other purposes, such as removing flies.

Another participant (P6) described her first-hand experience purchasing a futurity winning horse (futurity is a type of competition, typically involving young horses, that offers lucrative prize money), who at the age of seven she described as “a medicine chest” that she had to “nurse” to keep going. She ascribed her horse’s ongoing musculoskeletal problems to being ridden and competed as a two-year-old. Competing two-year-old horses in racing and reining, was raised as a welfare concern by several participants.

This is why most racehorses… you don’t see out and around after they’re five or six because they’ve broken down. Stock horses are the same. They put them in early. They do two-year-old classes and they camp draft them. They’re done… their joints are done, their heads are done, their brains are fried. [P6, female, advanced dressage rider].

The other approach adopted by participants was focusing on ‘other sports’ when discussing their horse welfare concerns. The sports usually identified by participants in this context were racing and reining. Participants suggested that within these two sports it was generally accepted that horse welfare was poor, however, the study did not include any participants currently riding in racing or reining. Despite this limitation, several participants had first-hand knowledge of these sports either as former competitors or employees. One participant described her experience while working at a racing stable of seeing a young horse abused during the horse’s initial training:

There were long yearlings that were… 18 months old, coming in for training, like they were just, they were big, fluffy foals. And they come in and, you know, they wouldn’t stand. I saw one that wouldn’t stand up at the wash bay… because she was a baby, so the trainer flogged her. Like physically beat her because he was angry. [P18, female, intermediate dressage rider].

Another participant who had grown up in a “[horse] racing town” did not elaborate on details of what she had seen but clearly articulated the gap between what equestrians think privately and what they are prepared to say publicly about horse welfare in some equestrian sports.

Wouldn’t publicly say it, but the racing industry, I think is really poor… no one really quite knows what goes on in the background but I’ve seen it, some pretty horrible stuff. [P16, female, intermediate trail rider].

Regardless of whether participants focused on ‘other people’ or ‘other sports’, common to all participants, was the suggestion that where poor horse welfare existed, it existed outside their sphere.

I don’t see personally, because I’m in my little bubble I suppose… I don’t personally see a lot of abuse… most of the horses I see are looked after well, and all that sort of stuff breaks my heart when you hear about horses that are starving to death and all that sort of thing. But yeah, so I think on the whole, they’re looked after pretty well and it… sort of pales into insignificance when you know what’s happening to a lot of animals in some countries where they’re absolutely tortured. So, I think that most people that I know, animal welfare is really high in their priorities. [P15, female, advanced dressage rider].

The other feature common to all participants was their concern for privacy. Almost every participant checked during or directly after the interview that their responses would remain anonymous. Others have reported there may be a stigma around the term ‘welfare’ and a reluctance among equestrians to discuss horse welfare (Furtado et al. Reference Furtado, Preshaw, Hockenhull, Wathan, Douglas, Horseman, Smith, Pollard, Pinchbeck, Rogers and Hall2021). Our results support these findings, and the gap we identified between public statements and private thoughts on horse welfare perhaps belie a degree of vulnerability felt by many equestrians. This sense of vulnerability was generally captured at the conclusion of interviews, often once the recorder had been turned off. At this point, several participants said something similar to ‘I’m different. Aren’t I?’ This question appeared to be an appeal for reassurance that they were different from typical equestrians, and their horses did indeed enjoy good welfare. What is underlying this vulnerability remains uncertain. As no validated tool for assessing ridden horse welfare is available (Furtado et al. Reference Furtado, Preshaw, Hockenhull, Wathan, Douglas, Horseman, Smith, Pollard, Pinchbeck, Rogers and Hall2021; Luke et al. 2022b), and in the absence of such a tool, it is possible equestrians feel ill-equipped to confidently assess horse welfare for themselves, so they depend on unreliable proxies and the confirmation of others. Alternatively, they may fear social sanctions if they break the norm and speak out, or it could be both or something else entirely. While further research into these questions is needed, identifying there is widespread latent concern for horse welfare among equestrians affords a significant opportunity for improving horse welfare if that concern can be translated into action.

From individual equestrians to influential groups in the horse industry

The final aspect of our analysis examined the themes using a systems thinking lens. Examination highlighted alignments and misalignments between individual horse owners’ understandings and perceptions regarding horse welfare and those of various influential groups within the horse industry, including equestrian organisations, veterinarians, and the general (non-horse-owning) public (see Figure 1 for details of horse industry systems map).

Participants’ understanding of horse welfare generally aligned with how equestrian organisations understand horse welfare, including the international peak body, the Federation Equestre Internationale, and its subsidiary, Equestrian Australia (Federation Equestre Internationale 2023) and local equestrian body the Australian Campdrafting Association (Australian Campdraft Association 2022). This finding was not unexpected given equestrian organisations are comprised mostly of equestrians. As experts on animal health, veterinarians tend to focus on the biological functioning of an animal as indicative of animal welfare (Fraser et al. Reference Fraser, Weary, Pajor and Milligan1997; Chapman Reference Chapman2017) which also aligns with participants’ understanding of horse welfare found in this study. However, there are calls from some within equine veterinary science (McGreevy et al. Reference McGreevy, McLean, Buckley, McConaghy and McLean2011; Chapman Reference Chapman2017; Doherty et al. Reference Doherty, McGreevy and Pearson2017) and society generally (Taylor Reference Taylor2022) for all stakeholders to embrace a more holistic understanding of horse welfare, such as the Five Domains Model (Mellor et al. Reference Mellor, Beausoleil, Littlewood, McLean, McGreevy, Jones and Wilkins2020). The growing misalignment between the industry’s understanding of horse welfare and society’s changing views fuel the increasing threat to the industry’s social licence to operate (Douglas et al. Reference Douglas, Owers and Campbell2022; Heleski Reference Heleski2023).

Participants’ dismissal of ‘problem’ horse behaviour and tendency to attribute it to a character flaw of the horse aligns somewhat with many veterinarians’ approach to ‘problem’ behaviour. Often when interacting with horses, both owners and veterinarians adopt a ‘just get it done’ approach (Beaver & Höglund Reference Beaver and Höglund2015). A veterinarian may face external pressures, such as subsequent appointments and financial concerns, which limit their capacity to take a more welfare-driven approach. However, veterinarians’ continued reliance on pain-based restraints, such as ear or nose twitching (Pearson et al. Reference Pearson, Reardon, Keen and Waran2020; Carroll et al. Reference Carroll, Sykes and Mills2022) to shut down unwanted behaviour is inconsistent with good horse welfare (Doherty et al. Reference Doherty, McGreevy and Pearson2017). It could also inadvertently reinforce equestrians’ perceptions that ‘problem’ horse behaviour should not be tolerated, and pain is an acceptable approach to eliminating it. Moreover, the ‘just get it done’ approach does not align with the positive reinforcement training approach to animal management widely practiced in other animal use industries, such as zoos (Ward & Melfi Reference Ward and Melfi2013). A recent audit of North American zoo visitors found they were more sensitive to zoo animals’ affective states than their physical health (Veasey Reference Veasey2022), which is likely a factor in their shift to more animal-centric training. The author went on to state “failure to meet the psychological needs of zoo animals should be considered as an existential threat to the [zoo] sector” (Veasey Reference Veasey2022; p 305). This observation of non-experts’ sensitivity to animals’ affective state may explain society’s growing unease with respect to sport horse welfare. Moreover, failure to meaningfully address society’s concerns about horse welfare may similarly represent an existential threat to the industry, with a recent article regarding equestrian sport’s social licence to operate suggesting “this is real; this is a threat; and the horse industry should consider themselves put on notice” (Heleski Reference Heleski2023; p 1). Minimisation of horse welfare concerns by our participants aligns with the public narrative of equestrian organisations, such as the FEI (Federation Equestre Internationale 2023) and Racing Australia who consistently maintain they adhere to “world’s best practice of animal welfare” (Racing Australia 2022; p 3), but generally say very little about the welfare status of horses within their sport. As discussed, the continued dismissal of society’s concerns for horse welfare by the industry, often justified by saying the public are non-experts and/or “do not understand the nature of the sport” (Chapman Reference Chapman2017; p 41) may prove a high-risk strategy.

Study limitations

The findings of this study were based on 19 semi-structured interviews of amateur equestrians from Victoria, Australia, and as such the findings have limited generalisability. However, an anonymous online survey (a methodology that allows participants to share their thoughts privately) found 78% of the 28,000 equestrians who participated were concerned about horse welfare (Waran Reference Waran2023). The results from Waran’s very large quantitative study support the findings of this small qualitative study, highlighting the strength of combining both quantitative and qualitative research methodologies. Considering these two studies together suggests, despite the small sample size, the findings from this study may relate to a wider equestrian population, although to confirm this, further research in other regions is needed.

In addition to sample size, the positionality of this study may also be a limitation. As mentioned earlier, whether explicit or implicit, researchers play an active role in all stages of research, from what they choose to study and the questions they ask, to how they analyse and interpret their data. Typically, much animal welfare research takes a human-centric standpoint (Fragoso et al. Reference Fragoso, Capilé, Taconeli, de Almeida, de Freitas and Molento2023), however, in this study an equine-centric view was adopted to highlight how humans’ conceptualisation of welfare positively or negatively affects horse welfare. Moreover, in reporting these results, the authors based their analysis on the data available, which is necessarily incomplete (Capra & Luisi Reference Capra and Luisi2014). So, while the data are interpreted using the most up-to-date science available, alternative explanations are possible. Therefore, these results must be interpreted cautiously, remembering that the analysis is based on the Five Domains Model of animal welfare, which has its own set of values and assumptions.

Animal welfare implications and conclusion

In this study we clearly identified a misalignment between how horse welfare is conceived and perceived among industry ‘insiders’ (individual horse owners, veterinarians, and equestrian organisations) and ‘outsiders’ (the general public and animal welfare scientists who advocate for expanded conceptualisations of animal welfare, such as the Five Domains Model). Furthermore, we found equestrians’ public assessments of horse welfare often do not align with what they think privately. These findings highlight the need for applied research and programmes that provide a safe space for equestrians to openly explore their concerns and help translate them into actions. Participatory programmes, underpinned by a partnership mindset, that engage all stakeholders and facilitate knowledge exchange are an example of such a strategy. Similar ‘bottom up’ approaches have been successful in areas such as healthcare (Haldane et al. Reference Haldane, Chuah, Srivastava, Singh, GCH, Seng and Legido-Quigley2019) and environmental education (Ardoin et al. Reference Ardoin, Bowers and Gaillard2020). The growing number and volume of scientists and citizens voicing concerns for ridden horse welfare in equestrian sport (Jones & McGreevy Reference Jones and McGreevy2010; McLean & McGreevy Reference McLean and McGreevy2010a; Taylor Reference Taylor2022) along with the continued questioning of the ethics of using any animals in sport (Forry Reference Forry and Klein2016) demonstrate the need for new solutions to improve horse welfare is urgent if equestrian sport is to have a long-term future.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/awf.2023.79.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful insights and suggestions. We would also like to thank the equestrians who generously volunteered for this research.

Competing interest

None.