Introduction

The adaptability of horses sees them bred for many different types of activity (e.g. breeding, non-competitive recreational riding, leisure and sport, education) and kept in a variety of different housing and management conditions that could potentially impact upon their welfare (McGreevy Reference McGreevy2004; Visser et al. Reference Visser, Neijenhuis, De Graaf-Roelfsema, Wesselink, De Boer, van Wijhe-Kiezebrink, Engel and van Reenen2014; Dalla Costa et al. Reference Dalla Costa, Dai, Lebelt, Scholz, Barbieri, Canali and Minero2017b).

The most common housing system in Western countries is single boxes (Thorne et al. Reference Thorne, Goodwin, Kennedy, Davidson and Harris2005; Dalla Costa et al. Reference Dalla Costa, Murray, Dai, Canali and Minero2014b) with the literature stating that the proportion of sport horses stabled in single boxes ranges from 32 to 90% in different nations (Hotchkiss et al. Reference Hotchkiss, Reid and Christley2007; Leme et al. Reference Leme, Parsekian, Kanaan and Hötzel2014; Visser et al. Reference Visser, Neijenhuis, De Graaf-Roelfsema, Wesselink, De Boer, van Wijhe-Kiezebrink, Engel and van Reenen2014; Hockenhull & Creighton Reference Hockenhull and Creighton2015; Larsson & Müller Reference Larsson and Müller2018). Welfare scientists consider single-box housing to present unfavourable aspects for horse welfare (Ruet et al. Reference Ruet, Lemarchand, Parias, Mach, Moisan, Foury, Briant and Lansade2019) since confinement prevents horses from engaging in highly motivated behaviours such as movement (Chaplin & Gretgrix Reference Chaplin and Gretgrix2010), social relationships (Søndergaard & Ladewig Reference Søndergaard and Ladewig2004) and natural feeding behaviour. As herbivores, grazing occupies up to 16 h of the feral horse’s day (Souris et al. Reference Souris, Kaczensky, Julliard and Walzer2007; Hampson et al. Reference Hampson, Laat, Mills and Pollitt2010a, Reference Hampson, Morton, Mills, Trotter, Lamb and Pollittb) while horses kept in single boxes traditionally have restricted access to high-fibre forage and their diet includes energy-dense cereal grains for ingestion more quickly (Jansson & Harris Reference Jansson and Harris2013). This daily ration can be consumed in less than 3 h (McGreevy et al. Reference McGreevy, Cripps, French, Green and Nicol1995), leaving horses without food for a large portion of their day, which could contribute to the development of stereotypies and gastric ulcers (Hoffman et al. Reference Hoffman, Costa and Freeman2009); moreover, decreased exposure to pasture is reported to be a risk factor for the onset of colic (Hudson et al. Reference Hudson, Cohen, Gibbs and Thompson2001). To better meet horses’ needs, in recent years, a shift to a diet higher in forages has been observed (Jansson & Harris Reference Jansson and Harris2013). Modern horse-feeding habits vary from country-to-country and most owners report feeding their horses a forage-based diet, supplemented with concentrated feeds (Hoffman et al. Reference Hoffman, Costa and Freeman2009; Auriane Hurtes Reference Hurtes2015; Murray et al. Reference Murray, Bloxham, Kulifay, Stevenson and Roberts2015; Kaya-Karasu et al. Reference Kaya-Karasu, Huntington, Iben and Murray2018; Larsson & Müller Reference Larsson and Müller2018), however ad libitum access to roughage still occurs infrequently (Kaya-Karasu et al. Reference Kaya-Karasu, Huntington, Iben and Murray2018; Larsson & Müller Reference Larsson and Müller2018). Horses are a social species (Mills & Nankervis Reference Mills and Nankervis1999), but traditional single boxes prevent them interacting freely with conspecifics, making it impossible to form cohesive social bonds. To overcome this, alternative box housing designs have been used. An alternative design sees stalls where the partition between two boxes is made up of a solid lower segment and an upper part consisting of vertical metal bars; this allows both visual and olfactory contact while limiting tactile contact (Gmel et al. Reference Gmel, Zollinger, Wyss, Bachmann and Freymond2022). So-called ‘social boxes’ are neighbouring stalls separated by ‘social bars’ (full height vertical bars spaced at 30 cm) making up half the partition and enabling visual, auditory, olfactory, and physical contact, while a solid partition also allows horses to withdraw (Gehlen et al. Reference Gehlen, Krumbach and Thöne-Reineke2021; Gmel et al. Reference Gmel, Zollinger, Wyss, Bachmann and Freymond2022). Unfortunately, little experimental work has been done addressing how well these alternative housing systems function (Hartmann et al. Reference Hartmann, Søndergaard and Keeling2012). Dalla Costa and colleagues (Reference Dalla Costa, Dai, Lebelt, Scholz, Barbieri, Canali and Minero2017b) highlighted that only 9.8% of horses in Europe are able to nibble and partly groom conspecifics and 22.3% have zero opportunity for social contact; visual or olfactory. Frustration, induced by the fundamental restrictions imposed by such housing causes a high proportion of horses to develop some kind of undesired behaviours (McGreevy et al. Reference McGreevy, Cripps, French, Green and Nicol1995; Cooper & Albentosa Reference Cooper and Albentosa2005): the reported prevalence of stereotypies in horses kept in boxes ranges from 14.4 to 32.5% (McGreevy et al. Reference McGreevy, Cripps, French, Green and Nicol1995; Sarrafchi & Blokhuis Reference Sarrafchi and Blokhuis2013; Muñoz et al. Reference Muñoz, Ainardi, Rehhof, Cruces, Ortiz and Briones2014; Ruet et al. Reference Ruet, Lemarchand, Parias, Mach, Moisan, Foury, Briant and Lansade2019).

Outdoor group housing (e.g. paddock or pasture) may be considered to have greater similarities with the living conditions of feral horses. Scientific research supports that housing animals in more natural conditions (e.g. group housing) can improve their welfare (for a review, see Fraser Reference Fraser2009). In fact, more natural housing conditions allow animals to perform species-specific behaviours freely, but, on the other hand, could threaten their welfare by enhancing the possibility of developing injuries and illnesses (Fraser Reference Fraser2008, Reference Fraser2009) and the reducing human-animal bond. As for horses, outdoor group housing is generally considered less practical for the caretaker, and potentially dangerous for horse health (McGreevy Reference McGreevy2004): by stabling their horses, owners consider themselves better able to manage nutrition, parasitic control, coat care, protection from atmospheric agents, while reducing the risks of aggressive interactions with other horses and the need for the horse to work for food (McGreevy Reference McGreevy2004). However, to date, no scientific data reporting a global assessment of welfare for horses in outdoor group-housing are available. In the south of France, a particular type of outdoor group-housing system entitled ‘parcours’ is traditionally adopted. ‘Parcours’ are semi-natural areas, grazed by domestic herbivores; consisting of spontaneous lawn, moor and wood proliferation located in areas of lowland, mountain, or marsh. Breeders explain that horses can eat grass, but also leaves or tree branches. In fact, horses were found to spend as much as 18% of their feeding time consuming such resources (Etienne et al. personal communication 2020). Horses, therefore, can contribute to the maintenance of these uncultivated areas, perhaps helping the prevention of vegetation fires. In fact, in the south of France, sheep are commonly used to maintain pastoral areas, by consuming plants liable to catch fire and by opening paths, which act as firebreaks. A recent study discussed how animals, including herbivores, can affect fire behaviour by modifying the amount, structure, or condition of fuel, as they eat those parts of the trees and bushes most likely to catch fire (Foster et al. Reference Foster, Banks, Cary, Johnson, Lindenmayer and Valentine2020). Thus, ‘parcours’ are considered environmentally sustainable, but an evaluation of the welfare of the horses kept in this management condition is necessary.

Horse welfare assessment could be based on the collection of animal-, resource- and/or management-based indicators. Animal-based indicators relate directly to the animal itself rather than to the environment in which the horse is kept (EFSA Panel on Animal Health and Welfare 2012), therefore these indicators can be collected in different housing conditions and used to infer how the animal is affected by external factors such as housing system. The AWIN welfare assessment protocol for horses, based on the Welfare Quality® principles and criteria, includes 25 animal-, resource- and management-based indicators (Dalla Costa et al. Reference Dalla Costa, Dai, Lebelt, Scholz, Barbieri, Canali, Zanella and Minero2016). The protocol has been applied by Dalla Costa et al. (Reference Dalla Costa, Dai, Lebelt, Scholz, Barbieri, Canali and Minero2017b) to collect welfare data in 355 single-stabled horses in Italy and Germany. Some adaptation to the AWIN protocol was suggested by the authors for assessing the welfare of horses kept in groups, however, to the authors’ knowledge, no specific data collection using the AWIN protocol on outdoor group-housed horses was published.

The aim of the present work was to collect data on the welfare of horses housed in a specific outdoor group-housing system known as ‘parcours’ via application of a complete and comprehensive welfare assessment method (the AWIN welfare assessment protocol for horses).

Materials and methods

‘Parcours’ description

‘Parcours’ are semi-natural areas grazed by domestic herbivores, such as horses. These areas have spontaneous and heterogeneous plant cover, with a low and very seasonal herbaceous production. They tend to prevail in difficult pedoclimatic environments (e.g. shallow soils, steep reliefs, frequent droughts), and are distinguishable by the degree of brushwood in lawns, moors and woods (Figure 1). In our study, herbaceous and woody plants provided a food resource that is heterogeneous in time and space. Grasses (e.g. brome, brachypod, dactyl) represented an important part of the horses’ diet. The horses consumed the green leaves with or without stems and ears, or only took the ears. The other herbaceous plants in the form of leaves or flowering stems were also widely consumed, whether legumes (e.g. vetch, clover) or others (e.g. thistle, yellow bedstraw, catananche). The horses also ate leaves and leafy branches of woody trees (e.g. beech, oak, service tree) and flowers (e.g. broom hispanica).

Figure 1. Example pictures of horses kept in “parcours”. a) Alpes Maritimes region; b) Cote d’azurregion, c) Provence region; d) Provence region.

Horses and facilities

Six farms in Région Sud Provence-Alpes-Côte d’Azur (France) were visited between June and November 2019. The following selection criteria for the facilities were employed: location in the Région Provence-Alpes-Cote d’Azur of France, adoption of an outdoor group-housing system such as a ‘parcours’ all-year-round, the keeping of at least ten horses aged older than one year. All the selected facilities were contacted via telephone and study participation was on a voluntary basis. On each farm, all horses older than one year were included, giving a total of 171 horses. Assessed animals had a mean (± SD) age of 8.95 (± 6.65), ranging from 1–25 years and consisting of both sexes (M = 61; F = 86; G = 61; Fpr = 10) and a variety of different breeds (Arabian: n =117, Anglo-Arabian: n = 1, Merens: n = 12, Camargue: n = 37, Not Assessed [NA]: n = 4) kept for different purposes (endurance: n = 102, leisure: n = 1, breeding: n = 52, retired: n = 6, NA: n = 10). Group sizes were variable (5.76 [± 3.62] individuals per group) as were areas utilised (from less than 1 ha to more than 500 ha; available space per horse ranging from 475 m2 per horse to more than 71,000 m2). A total of 33 groups were assessed, ten of which comprised both adult horses and foals (< one year old); welfare evaluation was not conducted on foals.

Welfare assessment

The second level of the AWIN Welfare assessment protocol for horses (AWIN 2015) was adopted. To adapt the assessment protocol to the outdoor group-housing system, the assessment protocol was modified: a total of 22 animal-based indicators and four resource-based indicators was included (Table 1). A veterinarian, experienced in horse behaviour and welfare evaluation, and co-author of the AWIN welfare assessment protocol for horses, performed all the assessments; detailed information regarding the training of the assessor on the protocol are reported in Dalla Costa et al. (Reference Dalla Costa, Dai, Lebelt, Scholz, Barbieri, Canali and Minero2017b). Horses were not restrained during evaluation and when it was not possible to touch the horse (e.g. avoidance reactions to Avoidance Distance test and/or Forced Human Approach test), the animal was evaluated from a maximum distance of 1 m. As for lameness evaluation, horses were observed during a spontaneous 10-m walk; if necessary, horses were gently encouraged to walk by the observer either vocally or by waving their arms. Detailed information regarding the welfare assessment (description, assessment and scoring methods of each welfare indicator) are reported in the AWIN welfare assessment protocol for horses (AWIN 2015), which is freely available: https://air.unimi.it/retrieve/handle/2434/269097/384836/AWINProtocolHorses.pdf.

Table 1. Welfare assessment protocol applied (modified from AWIN 2015).

* Results of these indicators are not presented in the paper.

Statistical analysis

Data collected on-farm were compiled into an Excel file and subsequently descriptive statistics were performed; the proportion of satisfactory or unsatisfactory scores for each welfare indicator was calculated.

Ethics

This study was conducted in compliance with Directive 2010/63/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 September 2010 on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes and followed the requirements of the International Society for Applied Ethology (ISAE). The study received approval from the Comité d’éthique de Val de Loire (number CE19-2020-1908-1). No animals underwent more than minimal distress and all procedures conformed to a routine assessment as in good farm practices. Written informed consent was gained from the farmers prior to taking part in this research.

Result and discussion

The results of the welfare assessment will be reported and discussed for each welfare principle (‘Good feeding’, ‘Good housing’, ‘Good health’ and ‘Appropriate behaviour’).

Good feeding

As regards the principle ‘Good feeding’ (Figure 2[a]), most of the assessed animals benefitted from appropriate nutrition (Body Condition Score [BCS] = 3; 59.6%). Extremes were rare (BCS = 1; 1.17% and BCS = 5; 1.17%). While not having a BCS of 3, most of the horses were over- (BCS > 3; 31%), rather than underweight (BCS < 3; 9.4%). Most of the overweight horses had a BCS = 4 (29.82%). Our results are in line with what has been previously observed in single-box-housed horses (Visser et al. Reference Visser, Neijenhuis, De Graaf-Roelfsema, Wesselink, De Boer, van Wijhe-Kiezebrink, Engel and van Reenen2014; Dalla Costa et al. Reference Dalla Costa, Dai, Lebelt, Scholz, Barbieri, Canali and Minero2017b), suggesting that group-housing in semi-extensive conditions such as ‘parcours’ does not represent a risk factor for poor nutrition. This result confirms what was suggested by Souris et al. (Reference Souris, Kaczensky, Julliard and Walzer2007), who observed that horses released in a natural environment with temperate climate are able to adapt their daily intake according to pasture availability and changes to climate, maintaining a good BCS or improving it. However, as reported by Dalla Costa et al. (Reference Dalla Costa, Murray, Dai, Canali and Minero2014b) “excellent body condition in a horse does not necessarily mean that foraging need is fulfilled”, which is not the case in group-housing at pasture. In fact, this housing condition allows horses to express natural grazing behaviour, satisfying the behavioural need to forage (Ninomiya et al. Reference Ninomiya, Kusunose, Sato, Terada and Sugawara2004). The restriction of this behavioural pattern and the reduced time dedicated to feeding imposed by box-housing are considered risk factors for stereotypies (for a review, see Sarrafchi & Blokhuis Reference Sarrafchi and Blokhuis2013) and colic development (Hudson et al. Reference Hudson, Cohen, Gibbs and Thompson2001). While avoiding the risk of under-nourishing horses, it is important to keep in mind that excessive body fat is related both to health problems (such as insulin resistance, colic, laminitis) and loss of performance (Geor & Acvim Reference Geor and Acvim2008; Carter et al. Reference Carter, Treiber, Geor, Douglass and Harris2009; Becvarova & Pleasant Reference Becvarova and Pleasant2012; Galantino-Homer & Engiles Reference Galantino-Homer and Engiles2012). To maintain an appropriate bodyweight, horses need a daily intake of their bodyweight in dry matter of forage and are readily able to match or even exceed their required daily dry matter intake with 24-h access to good quality pasture (Nadeau Reference Nadeau2006; Dowler et al. Reference Dowler, Siciliano, Pratt-Phillips and Poore2012; Siciliano Reference Siciliano and Zimmermann2012; Fiorellino et al. Reference Fiorellino, McGrath, Momen, Kariuki, Calkins and Burk2014). Five out of six farms in our study also provided horses with access to hay, in addition to pasture. This may have contributed to the high percentage of overweight horses in our sample. Owners may wish to supply hay to guarantee an adequate food intake; however, when grazing is permitted, this supplementation may put the animal at unnecessary risk of increasing weight. On the other hand, it was noticeable that the overweight horses were mostly Camargue and Merens. These are rustic breeds renowned for valuing their food very highly. Therefore, the natural and fodder resources provided on the ‘parcours’ seem excessively rich for some of these animals. Moreover, none of the farmers restricted the amount of pasture available to horses on a daily basis; a management trait that puts horses at risk of excessive weight gain (Dowler et al. Reference Dowler, Siciliano, Pratt-Phillips and Poore2012; Siciliano Reference Siciliano and Zimmermann2012).

Figure 2. Results of the welfare assessment (% of horses) related to the principle “goodfeeding” in parcour horses. a) Body condition score on a 5 point scale (AWIN 2015); b) water availability: type of waterpoint(automatic drinker, trough, natural water source); cleanliness of water point(partially dirty: water point dirty but water clean; dirty: water point andwater dirty) (AWIN 2015).

Horses had free access to a water-point (Figure 2[b]), which consisted of an automatic drinker (38.78%), a trough (28.06%) or a natural source of water (26.02%). In 7.14% of cases it was not possible to find and check the water-point, probably as a result of the size of the pasture in question. When a water-point was available, 27.55% of horses had access to clean water, while 25.51% had access to a partially dirty water-point (water-point dirty but water clean) and 11.22% to a dirty one (water-point and water dirty). Dalla Costa and colleagues (Reference Dalla Costa, Dai, Lebelt, Scholz, Barbieri, Canali and Minero2017b) found similar results: the drinkers of single-housed horses were partially dirty (24.5%) and dirty (17.5%). Water supply is a recognised issue in other farm animals kept on pasture with problems including short periods of water availability, water present only in certain areas where animals are grazing, absence of a man-made water supply and algal contamination depending on temperature and light (Kamphues & Ratert Reference Kamphues and Ratert2014). Moreover, the daily inspection and cleaning of water-points in very large pastures can present a challenge which may explain the numbers of partially dirty and dirty water-points found in the present study. Another important aspect is drinkability and accessibility of water-points, especially when the only source of water is a natural one. Water quality, in such cases, should be checked, to ensure appropriate standards of drinkability, i.e. chemical, physical, and biological characteristics (Kamphues & Ratert Reference Kamphues and Ratert2014). Cleanliness of water is of paramount importance, since horses are known to refuse dirty water (Friend Reference Friend2000); furthermore, water troughs and buckets should be cleaned regularly since shared water sources are a common source of disease (Lardy et al. Reference Lardy, Stoltenow, Johnson, Boyles, Fisher, Wohlgemuth and Lundstrom2008). Another aspect to take into account when considering horses kept on pasture is the water temperature in the trough: both cold water in winter and warm water in summer can lead to a decrease in water consumption (Kristula & Mcdonnell Reference Kristula and McDonnell1994), which is reportedly the primary predisposing factor for impaction colic (Kaya et al. Reference Kaya, Sommerfeld-Stur and Iben2009).

Good housing

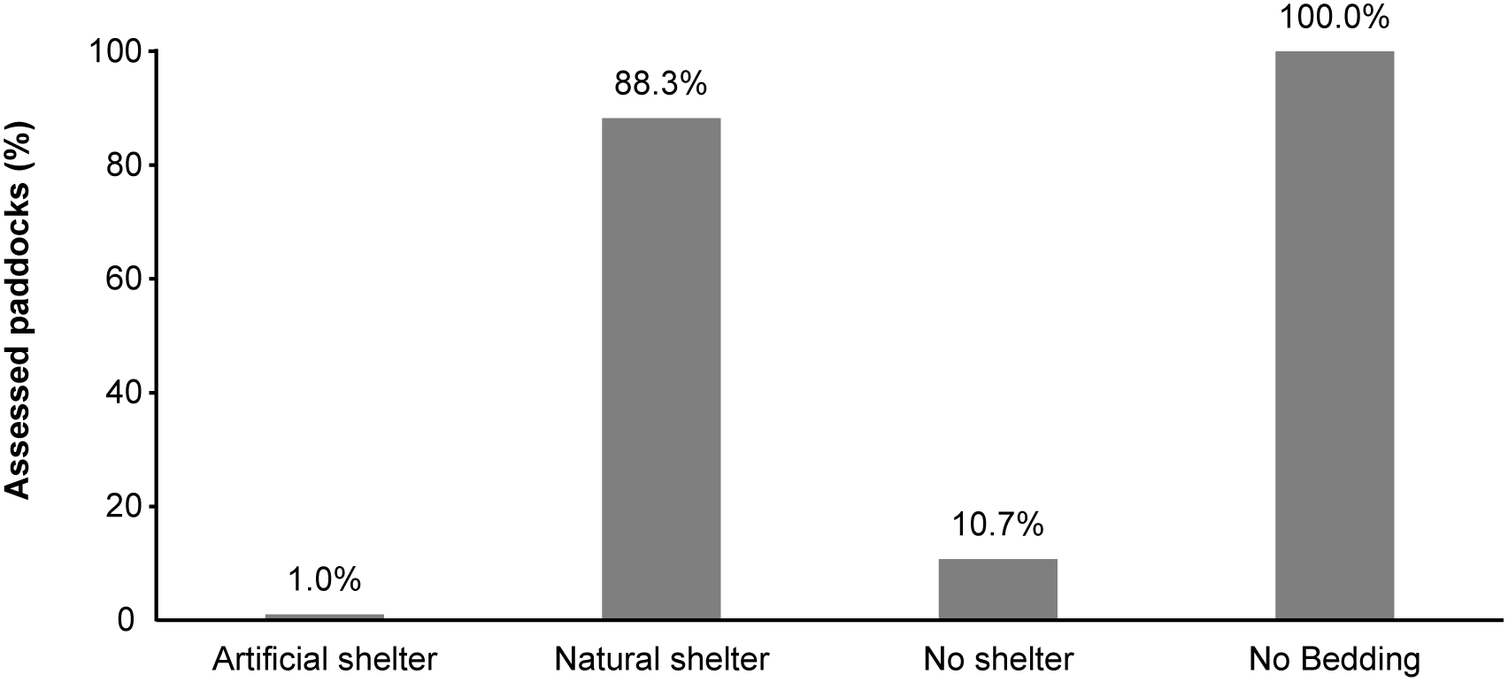

As regards the principle ‘Good housing’, all of the horses being evaluated were able to move freely throughout the entire day. For horses, movement is a highly motivated behaviour (Chaplin & Gretgrix Reference Chaplin and Gretgrix2010) and restrictions placed on it are known to impact upon their welfare (McGreevy et al. Reference McGreevy, Cripps, French, Green and Nicol1995; Cooper & Albentosa Reference Cooper and Albentosa2005). One possible concern regarding horses kept on pasture is their ability to shelter during inclement weather (Snoeks et al. Reference Snoeks, Moons, Ödberg, Aviron and Geers2015). In our sample, 10.7% of horses had no access to a shelter (Figure 3) and such an absence represents a considerable risk factor for horse welfare: the thermo-neutral zone for horses is estimated to lie within the range of 5 to 25°C (Morgan Reference Morgan1998) and when the environmental temperature deviates from this range, thermoregulation is achieved through changes in behaviour, including shelter-seeking (Cymbaluk Reference Cymbaluk1994; Snoeks et al. Reference Snoeks, Moons, Ödberg, Aviron and Geers2015). Several studies have demonstrated the need for horses to be able to access shelter during rainy or windy days (Tyler Reference Tyler1972; Duncan Reference Duncan1985; Autio & Heiskanen Reference Autio and Heiskanen2005; Mejdell & Bøe Reference Mejdell and Bøe2005; Ingólfsdóttir & Sigurjónsdóttir Reference Ingólfsdóttir and Sigurjónsdóttir2008). Shelter-seeking is also observed on hot, sunny days (Heleski & Murtazashvili Reference Heleski and Murtazashvili2010; Holcomb et al. Reference Holcomb, Tucker and Stull2014). Thermoregulation may not always be the main motivating factor for seeking shelter: horses also prefer to use a shelter to alleviate harassment from insects (Keiper & Berger Reference Keiper and Berger1982; Gòrecka-Bruzda & Jezieski Reference Gòrecka-Bruzda and Jezieski2007). The majority of horses in the present study had access to a shelter: natural, such as trees (83.3%), or artificial (1%). Although one publication (Snoeks et al. Reference Snoeks, Moons, Ödberg, Aviron and Geers2015) reported, given a choice, horses preferred artificial shelters over natural ones, especially during cold and rainy conditions, artificial shelters are difficult to provide when horses move over large areas as was the case in our study. It should also be taken into consideration that non-artificial shelters are more in keeping with the natural environment and that when only natural shelters are available, horses prefer to spend time under dense vegetation (Pratt et al. Reference Pratt, Putman, Ekins and Edwards2016).

Figure 3. Results of the welfare assessment (% of horses) related to the principle “Good housing”(shelter availability and bedding) in parcour horses.

None of the visited farms used bedding (Figure 3), it may be hypothesised that the owners of horses kept on ‘parcours’ did not consider it necessary to provide bedding, since horses were able to choose a more comfortable spot upon which to lie down. It is worth noting that bed sores were not observed (see Good health).

Good health

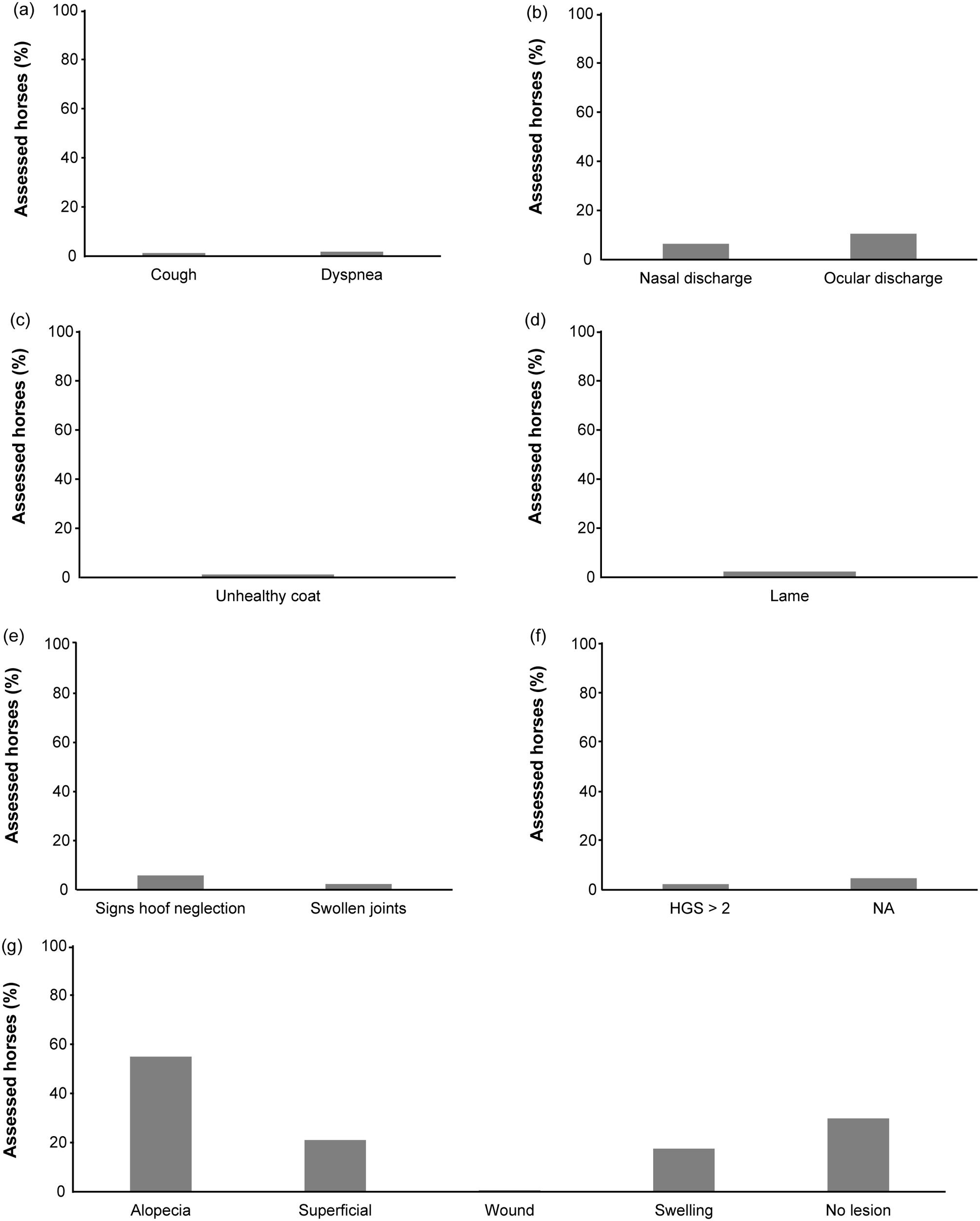

The studied horses generally benefitted from good health and none presented any severe health conditions (Figure 4). While we did not perform any clinical examination on assessed horses, indicators such as coughing, abnormal breathing, nasal and ocular discharge were chosen since they are well recognised symptoms of a diverse variety of respiratory problems (Halliwell et al. Reference Halliwell, McGorum, Irving and Dixon1993). These are reported to be common in horses kept in single boxes with a prevalence ranging between < 3 and 16.9% (Wheeler et al. Reference Wheeler, Christley and McGowan2002; Hotchkiss et al. Reference Hotchkiss, Reid and Christley2007; Visser et al. Reference Visser, Neijenhuis, De Graaf-Roelfsema, Wesselink, De Boer, van Wijhe-Kiezebrink, Engel and van Reenen2014). In ‘parcours’ housed horses, we found that 1.8% (3 out of 171) showed dyspnoea, 1.2% (2 out of 171) coughing, and 6.4% (11 out of 171) clear, serous nasal discharge, while none presented purulent or haematic discharge (Figure 3[a] and [b]). This prevalence is higher than found by Dalla Costa et al. (Reference Dalla Costa, Dai, Lebelt, Scholz, Barbieri, Canali and Minero2017b), but lower than has been reported for stabled horses (Wheeler et al. Reference Wheeler, Christley and McGowan2002; Hotchkiss et al. Reference Hotchkiss, Reid and Christley2007; Visser et al. Reference Visser, Neijenhuis, De Graaf-Roelfsema, Wesselink, De Boer, van Wijhe-Kiezebrink, Engel and van Reenen2014). Since respiratory problems have been associated with the housing system, stable hygiene practices and bedding choice (Clarke Reference Clarke1987; Halliwell et al. Reference Halliwell, McGorum, Irving and Dixon1993), our results can perhaps be attributed to low ammonia levels, dust concentration and fungal presence in an open-air environment. Similarly, a low prevalence of ocular discharge was observed (10.5% of horses; 18 out of 171) and no individuals showed a thick, purulent or haematic discharge. Visser et al. (Reference Visser, Neijenhuis, De Graaf-Roelfsema, Wesselink, De Boer, van Wijhe-Kiezebrink, Engel and van Reenen2014) reported a prevalence of 20% of ocular discharge in stabled horses and their risk factors for this were the number of horses housed in the same stable and the absence of a viable air outlet.

Figure 4. Results of the welfare assessment (%of horses) related to the principle “good health” in parcour horses. a) cough and dyspnoea; b) nasal and ocular discharges; c) coat condition; d) lameness; e) signs of hoof neglect andswollen joints; f) HGS; g) skin lesions.

Lameness is generally considered to be a common cause of welfare impairment in horses and in stabled horses the reported prevalence ranges from 13 to 33% (Murray et al. Reference Murray, Walters, Snart, Dyson and Parkin2010; Ireland et al. Reference Ireland, Clegg, Mcgowan, McKane, Chandler and Pinchbeck2012; Lesimple et al. Reference Lesimple, Fureix, De Margerie, Sénèque, Hervé and Hausberger2012; Visser et al. Reference Visser, Neijenhuis, De Graaf-Roelfsema, Wesselink, De Boer, van Wijhe-Kiezebrink, Engel and van Reenen2014). In the present study, a much lower percentage was identified (2.3%) (Figure 4[d]). The cause of lameness was not investigated, but it is worth noting that one horse also showed swollen joints and three showed varying degrees of hoof neglect, which can be responsible for lameness. Several risk factors have been described for lameness: age (older horses are at greater risk of lameness), current use of horse (riding school use or recreation increases lameness risk), back pain caused by inappropriate saddle, foot problems, training regimen (using only one surface for training increases the risk of lameness) (Cooper & Albentosa Reference Cooper and Albentosa2005; Murray et al. Reference Murray, Walters, Snart, Dyson and Parkin2010; Visser et al. Reference Visser, Neijenhuis, De Graaf-Roelfsema, Wesselink, De Boer, van Wijhe-Kiezebrink, Engel and van Reenen2014). It could be hypothesised that horses kept in ‘parcours’, having greater scope to exercise freely on different grounds, developed a musculoskeletal system better adapted to a range of surfaces and exercises, consequently reducing the risk of injuries during sports activities. Murray et al. (Reference Murray, Walters, Snart, Dyson and Parkin2010) also identified the lack of warm-up before exercise as a risk factor for musculoskeletal injuries and subsequent lameness. Horses kept on ‘parcours’, permanently able to move, could perform a ‘natural warm-up’, decreasing the risk of lameness.

In the present study only 29.8% of horses presented an intact skin (Figure 4[g]). It is worth noting that most of the horses (53.8%) showed areas of alopecia, while 23.4% presented superficial lesions and 0.6% deep wounds (Figure 4[g]). These results differ from those of Dalla Costa and colleagues (Reference Dalla Costa, Dai, Lebelt, Scholz, Barbieri, Canali and Minero2017b) on single-housed horses, where the majority of horses had no skin lesions. The causes of skin lesions were not investigated, but alopecia is often related to itch which may be caused by insect bites, ectoparasites or allergic reactions. In fact, 18.8% of horses showed swellings on the skin, probably related to insect biting. Fly control at pasture may represent a challenge for owners; some management practices (such as the use of repellents, fly traps, protective masks and/or rugs, and the frequent removal of dung) may help in reducing fly bites (Gòrecka-Bruzda & Jezieski Reference Gòrecka-Bruzda and Jezieski2007). It should, however, be noted that only a limited number of products are currently approved for treatment of ectoparasites in horses, meaning that these products should be used judiciously with special emphasis on the safety of these products for horses, people and the environment (Karasek et al. Reference Karasek, Butler, Baynes and Werners2020). Superficial lesions may be caused by scratches from branches or rocks, or through aggressive interactions with other horses. One of the major concerns preventing owners from keeping their horses in a group is the possibility of aggressive behaviours causing lesions or restricted access to crucial resources (McGreevy Reference McGreevy2004). However, several studies have demonstrated that the level of aggression significantly decreases with increased group stability (van Dierendonck et al. Reference van Dierendonck, Sigurjónsdóttir, Colenbrander and Thorhallsdóttir2004; Hartmann et al. Reference Hartmann, Søndergaard and Keeling2012; Sigurjónsdóttir & Haraldsson Reference Sigurjónsdóttir and Haraldsson2019) and with increased area availability per horse (up to at least 300 m2) (Flauger & Krueger Reference Flauger and Krueger2013). Indeed, group stability, as with feral horses (Waring Reference Waring2003; Stanley et al. Reference Stanley, Mettke-Hofmann, Hager and Shultz2018), allows stable dominance relationships and friendship networks, reducing numbers of aggressive interactions among members (Sigurjónsdóttir et al. Reference Sigurjónsdóttir, van Dierendonck, Snorrason and Thórhallsdóttir2003; van Dierendonck et al. Reference van Dierendonck, Sigurjónsdóttir, Colenbrander and Thorhallsdóttir2004; Fureix et al. Reference Fureix, Bourjade, Henry, Sankey and Hausberger2012; Granquist et al. Reference Granquist, Gudrun and Sigurjonsdottir2012; Hartmann et al. Reference Hartmann, Søndergaard and Keeling2012). Equally, recurrent changes in group composition sees a rise in the number of interactions, mainly agonistic ones (Hartmann et al. Reference Hartmann, Christensen and Keeling2009; Fureix et al. Reference Fureix, Bourjade, Henry, Sankey and Hausberger2012). This is explained by the fact that in stable groups each individual is aware of the social network and, consequently, the aggression is ritualised (Rutberg & Greenberg Reference Rutberg and Greenberg1990; Heitor et al. Reference Heitor, do Mar and Vincente2006; Hartmann et al. Reference Hartmann, Søndergaard and Keeling2012). Therefore, the risk factor for injuries should not be considered a result of the group housing per se, but more the lack of group stability (Fureix et al. Reference Fureix, Bourjade, Henry, Sankey and Hausberger2012). In our study, the mean number of aggressive interactions per horse per hour was 0.76 (± 1.2) (data not shown) which seems somewhat low compared to data reported for horses observed in semi-natural conditions (Flauger & Krueger Reference Flauger and Krueger2013) and the average area per horse was much greater than 300 m2. Therefore, these two factors do not seem to be the main reasons for the large proportion of observed skin lesions.

It could be hypothesised that, compared to owners who keep their horses in boxes, owners favouring horses at pasture are perhaps less attentive to hoof care, especially when horses are not used on a daily basis for sport activities. However, only 5.8% of horses (ten out of 171) in our sample presented some degree of hoof neglect (Figure 3[e]); a result comparable with the prevalence reported elsewhere (Dalla Costa et al. Reference Dalla Costa, Dai, Lebelt, Scholz, Barbieri, Canali and Minero2017b). Regardless of housing system, daily care and regular routine farriery are fundamental since neglect of these practices predisposes to the development of foot problems (Kummer et al. Reference Kummer, Geyer, Imboden, Auer and Lischer2006; van Eps Reference van Eps2012; Leśniak et al. Reference Leśniak, Williams, Kuznik and Douglas2017).

The Horse Grimace Scale (HGS) is a facial-expression-based pain coding system (Dalla Costa et al. Reference Dalla Costa, Minero, Lebelt, Stucke, Canali and Leach2014a) which can be considered a specific tool to assess pain in horses (Dalla Costa et al. Reference Dalla Costa, Bracci, Dai, Lebelt and Minero2017a) and easily applicable by non-expert observers (Dai et al. Reference Dai, Leach, Macrae, Minero and Costa2020). An HGS value⩾2 is considered an indicator of pain (Dalla Costa et al. Reference Dalla Costa, Pascuzzo, Leach, Dai, Lebelt, Vantini and Minero2018). In the present study, the HGS score was ⩾2 in 2.3% of cases (Figure 4[f]), this is similar to horses kept in single boxes (Dalla Costa et al. Reference Dalla Costa, Dai, Lebelt, Scholz, Barbieri, Canali and Minero2017b); thus, confirming that horses were regularly checked for possible pain-related conditions. It is important to underline that in 4.6% of cases, it was not possible to assess HGS, meaning that horses were not close enough to permit an accurate scoring or were wearing masks partly covering their head.

Appropriate behaviour

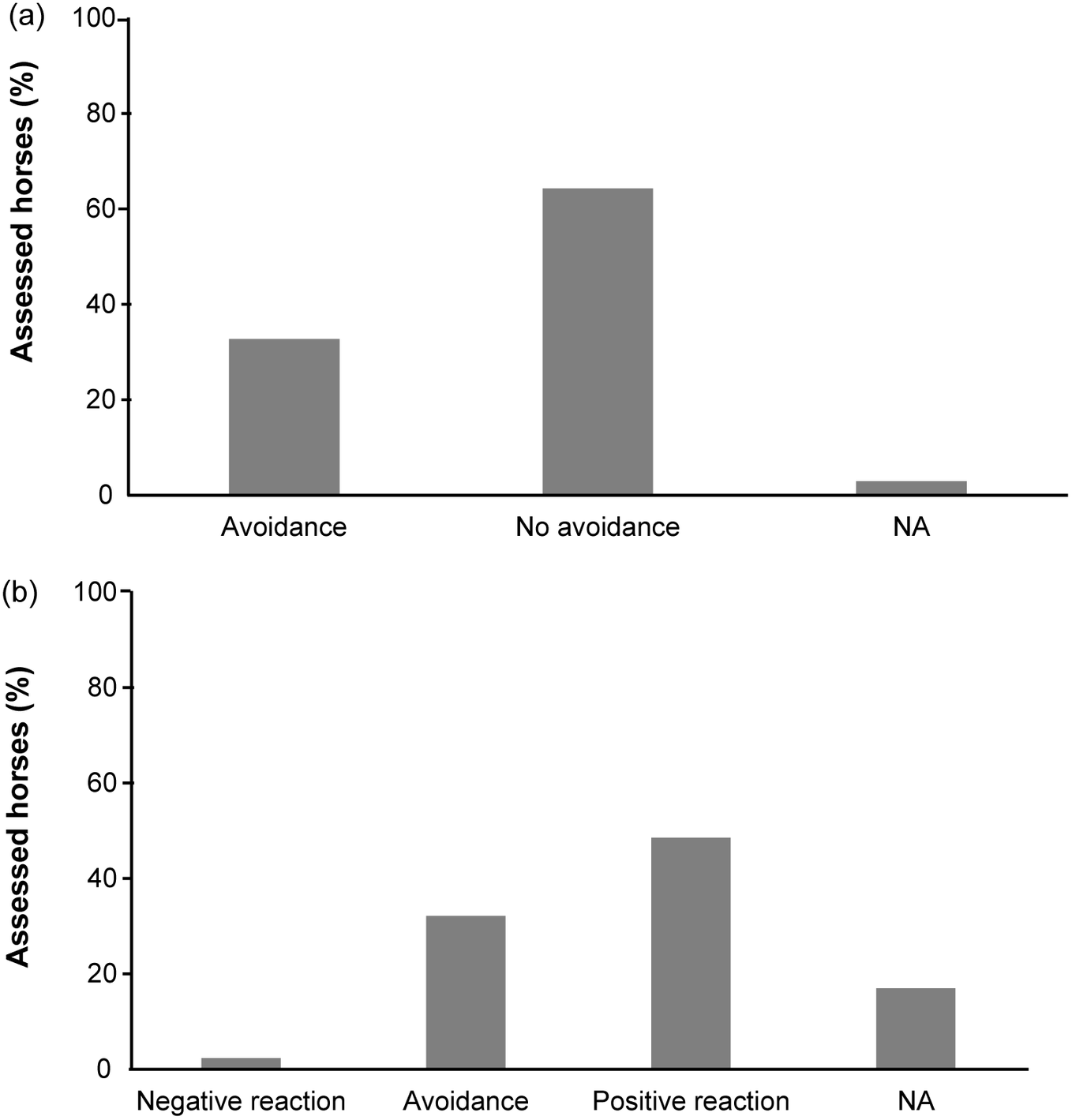

Figure 5 reports results regarding the principle ‘Appropriate behaviour.’ Regarding social interaction, horses were kept in groups of different dimensions (mean 5.76 [± 3.62] conspecifics); ten groups included foals and nine included stallions. Only one stallion (0.6%), used for reproduction, was kept alone; visual and olfactory contact with other horses were possible for this individual. In both Italy and Germany it was reported that 22.3% of stabled horses had no scope for visual or physical contact (Dalla Costa et al. Reference Dalla Costa, Dai, Lebelt, Scholz, Barbieri, Canali and Minero2017b). Hockenhull and Creighton (Reference Hockenhull and Creighton2015) reported that in the UK 3% of horses face the same situation. As horses are a social species, social interaction with conspecifics is a behavioural need. The restriction imposed by housing conditions is deemed responsible for the development of a range of abnormal behaviours, such as stereotypies (McGreevy et al. Reference McGreevy, Cripps, French, Green and Nicol1995; Cooper & Albentosa Reference Cooper and Albentosa2005). Previous studies reported a prevalence of stereotypies in horses kept in single boxes ranging from 14.4 (Ruet et al. Reference Ruet, Lemarchand, Parias, Mach, Moisan, Foury, Briant and Lansade2019) to 32.5% (McGreevy et al. Reference McGreevy, Cripps, French, Green and Nicol1995), while in the present study we observed only 1.2% of stereotypies (two horses out of 171). A recognised risk factor for stereotypy development is the frustration of fundamental needs (e.g. grazing, movement, social relationship) (McGreevy et al. Reference McGreevy, Cripps, French, Green and Nicol1995; Cooper & Albentosa Reference Cooper and Albentosa2005); being housed in groups and having permanent access to pasture can therefore explain this low prevalence of stereotypies observed here.

Figure 5. Results of the welfare assessment (% of horses) related to the principle“appropriate behaviour” in parcour horses. a) Avoidance Distance test; b)Forced Human Approach test.

A possible concern preventing owners from keeping their horses at pasture is the difficulty of catching them (McGreevy Reference McGreevy2004). Counter-intuitively, 64.3% of horses in our sample showed no avoidance reactions when approached by the unknown assessor, similarly to the box-housed horses included in the AWIN population (Figure 5[a]). Moreover, 48.5% of horses showed positive responses to the Forced Human Approach (FHA) test (Figure 5[b]). In the FHA test, 32.2% of horses showed avoidance reaction, only 2.3% showed some aggressive behaviours; for 17% of horses it was not possible to perform the FHA test, because they went away from the observer during the Avoidance Distance (AD) test (Figure 5[b]). In a previous study on horses kept in single boxes, a larger proportion exhibited positive reactions to the AD test (Dalla Costa et al. Reference Dalla Costa, Dai, Lebelt, Scholz, Barbieri, Canali and Minero2017b); however, it is worth pointing out that the horses included in the present study preferred to move away from the observer, when unwilling to interact, instead of being aggressive, thus potentially reducing the risks for human injuries. Similar results were obtained in a previous study comparing two groups of ponies kept in a group on pasture or housed in individual boxes, in restricted conditions (Dany et al. Reference Dany, Vidament, Yvon, Reigner, Barrière, Riou, Layne, Lansade, Minero, Dalla Costa and Briant2017). Avoidance from an undesired stimulus is a natural behaviour for a prey species and suggests that observed horses had the perception of being able to control their own environment, deciding when to interact instead of feeling forced to do so with humans. Interactions with owners were not formally noted, however the assessor observed that most of the horses were more friendly with the owner and showed avoidance reactions less frequently. To overcome the catching difficulties potentially perceived by owners (McGreevy Reference McGreevy2004), specific training to teach the horse to come when called using non aversive methods may be useful (Sankey et al. Reference Sankey, Richard-Yris, Leroy, Henry and Hausberger2010). Training could also help in simplifying horses’ daily inspections.

Animal welfare implications

Outdoor group housing could be seen as having more similarities with feral horse living conditions, however it is considered to increase the risk of developing injury and illness. This study reports, for the first time, results from a comprehensive welfare data collection carried out on group-housed horses on ‘parcours.’ The reported outcomes can help in creating a common database on horse welfare status and understanding underlying relations with housing conditions and management.

Conclusion

The application of a complete and comprehensive assessment method to evaluate the welfare of group-housed horses kept on ‘parcours’ proved to be feasible and useful in identifying areas of practice that can be linked to good welfare and areas where improvements are required. The findings showed that horses kept on ‘parcours’ presented few abnormal behaviours such as stereotypies, could move freely for most of the day and interact with conspecifics, at the same time maintaining a good relationship with humans. The main welfare concerns were related to the availability of water sources, lack of artificial shelters and presence of superficial integument alterations such as alopecia, probably linked to sub-optimal control of external parasites. Excessive weight gain was observed in a significant proportion of horses (especially in those facilities where hay was administered in addition to natural resources). Study limitations are mainly represented by the relatively small number of facilities involved in this study, especially in terms of geographical location, thus the sample may not accurately reflect the welfare status of all the horses kept on ‘parcours’ or at pasture. Stronger conclusions could be derived from a direct comparison, adopting an inferential statistical approach, on data collected using the same welfare assessment method on horses kept under different management systems in similar geographical locations. Following the same approach, further harmonised data collection is required to enlarge the sample and perhaps include other housing conditions.

Acknowledgements

Authors are grateful to the FEADER and the PACA region for their financial support and wish to thank all the farmers for their participation in the project.

Competing interest

None.