INTRODUCTION

Recent work by archaeologists and anthropologists has focused on fundamental issues related to what it means to be a person—issues to be considered, if not always easily untangled, in order to better understand basic elements of being and experience within the cultural settings that we study. These investigations have focused on several important topics. First, they have examined the ways in which a person is defined and bounded. For instance, persons may be understood as individual or dividual (that is, indivisible versus divisible), per Strathern's (Reference Strathern1988) seminal discussion of different modes of persons, decentering the presumed centrality of independent, contained persons (see also Bird-David Reference Bird-David1999; Brück Reference Brück2001; Fowler Reference Fowler2001, Reference Fowler2004, among others). Second, recent investigations have queried how various persons connect and interact. Personhood can be productively understood as an “ongoing act of production” (Brück Reference Brück2004:211) within a relational model, hearkening back to Mauss (Reference Mauss and Halls1990) and discussed through partible and permeable modes that indicate the possibility of blending, division, or porosity in how bodies and persons are culturally conceptualized (see particularly Busby Reference Busby1997; recent broader relational discussions in Fowler Reference Fowler2016 and Watts Reference Watts2013; and consideration of relational personhood in Maya ethnographic contexts through a framework of inalienable possessions in Kockelman Reference Kockelman2007). This theme of personhood as enacted is also apparent through the relational elements of a reexamined animism (e.g., Bird-David Reference Bird-David1999; Harvey Reference Harvey2006; Ingold Reference Ingold2006). Third, recent work has raised possibilities about who or what might be considered a person. Such topics are explored in studies of non-human personhood and the criteria for this state (e.g., Brown and Walker Reference Brown and Walker2008; Hendon Reference Hendon and Harrison-Buck2012; Watts Reference Watts2013; Webmoor and Witmore Reference Webmoor and Witmore2008) and the position of human beings within organizational categories of personhood (e.g., Hallowell Reference Hallowell1960; Kohn Reference Kohn2013). These investigations engage with varied, locally defined, and contingent versions of personhood, recognizing that personhood is constructed and experienced differently in different times and places (see Fowler Reference Fowler2016; Joyce Reference Joyce2000a; Meskell Reference Meskell1999; Meskell and Joyce Reference Meskell and Joyce2003; Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson2017). In the process, this body of work has linked with important ontological queries (e.g., Alberti Reference Alberti2016; Alberti et al. Reference Alberti, Fowles, Holbraad, Marshall and Witmore2011; Halperin Reference Halperin2017; Harris and Robb Reference Harris and Robb2012; Harrison-Buck Reference Harrison-Buck2012; Henare et al. Reference Henare, Holbraad and Wastell2007; McAnany and Brown Reference McAnany and Brown2016; Viveiros de Castro Reference Viveiros de Castro1998) and with critical examinations of the disciplinary and cultural assumptions we bring to our work on these topics (e.g., Thomas Reference Thomas2015; Weismantel Reference Weismantel2015). This larger framework of scholarship guides my inquiries into ancient Maya personhood, grounded in depictions of non-human objects, and particularly objects shown with faces, on Classic period painted ceramic vessels.

Discussions of personhood in the ancient Maya world (ca. a.d. 250–900, in Mexico and Central America) have similarly centered on boundaries and contents of persons, actions and interactions that mark the presence (or absence) of personhood, and the location of personhood, or parts thereof, in non-human entities; I review key elements of these findings below. Some questions about Classic Maya non-human personhood remain as yet unanswered by these investigations, however, and are important for more clearly understanding how object persons obtained and experienced personhood. These include: what is the nature of the linkage between human beings and object persons, and how does personhood (or elements thereof) pass between them? Subsequently, what is the impact on an object of becoming personed—to what extent is an object person changed from its object state by obtaining personhood? These questions about the operation of non-human personhood for objects in Classic Maya contexts pertain to larger archaeological and anthropological discussions of personhood.

In what follows, I approach these questions through Classic Maya visual evidence. I focus on a particular domain in Classic Maya iconography: the visual phenomenon of faces depicted on non-human objects. By “faces,” I refer to representations of features that echo those that are typically found on human visages, showing some constellation of eyes, nose, and mouth. As discussed in greater depth below, I suggest that the presence of a face indicates potential for an entity (or an object) to act in person-like ways. I argue that close examination of the suite of “faced” objects in a dataset of Maya iconographic images from painted ceramic vessels reveals that, in Classic Maya contexts, personhood represents a resource and moveable substance that provides nuance on what it means to be a person for the ancient Maya. I suggest that Classic Maya personhood fundamentally does not require humans as a source, acting instead as an untethered resource that is accessed by entities (human or not) that are able to act in social, relational ways. Furthermore, examples of object personhood represent a state of identity in which essences of persons and objects coexist, opening possibilities for complicating categories of being in the ancient Maya world.

For this study, I use a relational stance to define persons and personhood, taking inspiration from Fowler and Harris's (Reference Fowler and Harris2015:129) discussion of “the paradox of deciding whether to approach things as ongoing relational processes or as bounded entities[,]” which allows for acknowledgment of distinct entities that contain specific properties but also positions them within webs of participation and relationships. I identify persons as those entities with qualities or capabilities that would allow them to fulfill social and cultural expectations of community members. That is, regardless of form or origin, entities that have and can meet needs related to communication, feeding, care, and interaction may be treated and recognized as persons, while also being marked by other qualities that characterize their natures.

CLASSIC MAYA PERSONS

Like many areas of Maya research that focus on conceptual realms, investigations into Classic ideas about personhood have frequently bridged evidence from ancient and modern Maya contexts and, indeed, ethnographic investigations have shed light on modern Maya ideas about personhood (e.g., Astor-Aguilera Reference Astor-Aguilera2010; Brown Reference Brown2004, Reference Brown and Aveni2015; Brown and Emery Reference Brown and Emery2008; Gossen Reference Gossen and James Arnold1996; Kockelman Reference Kockelman2007; Watanabe Reference Watanabe1992). Ethnographic evidence, particularly related to ontological ways of being that may be relatively durable over time, has the potential to complement or flesh out evidence deriving from earlier eras but must be used with caution, given the clear changes that have occurred between the Classic period and the present; an emphasis on personhood as profoundly contextual means that differences between these eras should not be glossed over. For this reason, I primarily review Classic-period evidence on personhood here.

Boundaries and Contents of Persons

Multiple scholars have engaged with questions about the boundaries of Classic period Maya human selves (e.g., Geller Reference Geller2012; Gillespie Reference Gillespie, Borić and Robb2008; Hendon Reference Hendon and Harrison-Buck2012; Houston et al. Reference Houston, Stuart and Taube2006; Meskell and Joyce Reference Meskell and Joyce2003), agreeing that Classic Maya bodies were dividual (or divisible), while also acknowledging the challenges and limitations of exploring this topic without living informants (Hendon Reference Hendon and Harrison-Buck2012; Houston et al. Reference Houston, Stuart and Taube2006:100). Using hieroglyphic, iconographic, and sculptural evidence, Houston et al. (Reference Houston, Inomata and Coben2006:98) suggest that the Classic Maya concepts of personhood involved a self that moved beyond the boundaries of particular bodies, yielding persons that were “extended and extendible.”

This extension of personhood beyond a particular human body is seen particularly vividly through carved stone monuments that impersonate—and, in fact, seem to contain elements of—human beings (e.g., Houston and Stuart Reference Houston and Stuart1998; Looper Reference Looper2003; Stuart Reference Stuart1996). Stelae thus embodied a “transcendence” or “essential sameness” between subject and object, or original and image (Houston and Stuart Reference Houston and Stuart1998:86–87; see analogous discussion of representations of gods in Houston and Stuart Reference Houston and Stuart1996). Discussion of the Maya ritual practice of impersonation (e.g., Houston Reference Houston, Inomata and Coben2006; Houston and Stuart Reference Houston and Stuart1998; Stone Reference Stone and Fields1991) indicates that “self” can be located in more than one location, can move from location to location, or can divide into multiple locations (Houston and Stuart Reference Houston and Stuart1998:81). The idea that personhood, or elements thereof, could move beyond the bounds of a particular human being and lodge in other locations is supported by the desecratory acts that were frequently visited upon such monuments in order to temper or deactivate their liveliness (e.g., Harrison-Buck Reference Harrison-Buck, Iannone, Houk and Schwake2017; Houston et al. Reference Houston, Stuart and Taube2006; O'Neil Reference O'Neil, Boldrick, Brubaker and Clay2013), recalling Strathern's (Reference Strathern1988) discussion of divisibility, and the flows of elements possible between dividuals. The presence of repeated representations of self (e.g., in the case of multiple Classic-era stelae representing a particular ruler [Looper Reference Looper2003]) also indicate a divisible self (Houston et al. Reference Houston, Stuart and Taube2006:101), though there is lack of clarity about whether all such representations would have been simultaneously and consistently persons, or if they were occasionally and contextually active as persons.

This divisible aspect of Classic Maya personhood is also evident through research into the multiple substances that constituted a Maya self, including things like the way (an animal co-essence), and k'uh (a concept of the divine) (Houston et al. Reference Houston, Stuart and Taube2006:79; Monaghan Reference Monaghan1998), some of which were able to enter and exit the body; ideas about parts of souls are evident in ancient Central Mexican concepts that may be relevant to the Maya, as well (Furst Reference Furst1995; López-Austin Reference López-Austin, Ortiz de Montellano and Ortiz de Montellano1988). Duncan and Schwarz (Reference Duncan, Schwarz, Osterholtz, Baustian and Martin2014) illustrated this sense of bodies that are not solidly bounded conceptually and materially in their discussion of a Maya mass grave, in which they argue for partible and permeable bodies and a sense of mosaic corporeality, thereby emphasizing the relational nature of Classic-era personhood in an embodied sense.

Personhood through Action and Interaction

The integrative relationships amongst multiple persons observed by Duncan and Schwarz (Reference Duncan, Schwarz, Osterholtz, Baustian and Martin2014), for example, is also discussed by scholars like Gillespie (Reference Gillespie2001:98) in the context of Maya socially constructed persons, who draw elements of personhood from a larger community (e.g., per the “house” concept), and Monaghan (Reference Monaghan1998:140), who argues for personhood as adhering not to individuals but rather within a collective (see also Houston [Reference Houston2014] and Hutson [Reference Hutson2010] for discussion of the importance of a relational stance in interpreting Maya contexts, and Harrison-Buck [Reference Harrison-Buck, Buchanan and Jacob Skousen2015] for thinking about the Maya cosmos through a relational lens). Hendon (Reference Hendon and Harrison-Buck2012:83) argues that objects have souls that can “enter into relations with other souls,” and participate in life cycles analogous to those of humans, suggesting another socially embedded commonality for persons no matter the form or type. This body of work points towards profoundly relational elements of personhood in ancient Maya contexts, and indicates the importance of examining how personhood operates between and among multiple entities. Indeed, some Mayanists have addressed what it means to be a person by focusing on action and interaction, and how appropriate actions and interactions define certain entities as meaningful members of the community (see Bachand et al. [Reference Bachand, Joyce and Hendon2003] for discussion of this in terms of precedent and citational practice). Houston et al. (Reference Houston, Inomata and Coben2006:174) have discussed bodily positioning (e.g., captives who are de-personed by being positioned beneath the feet of rulers) and expression (e.g., acceptable emotional displays; Houston Reference Houston2001) in terms of persons fulfilling their roles as community members; the implication is that those who do not position themselves correctly vis-à-vis others suffer some loss of standing in terms of their person-status. Other modes of relating that appear to be key in sustaining a person status include communication between persons (human and non-human), and the care-taking and addressing of person needs (such as feeding, dressing, and holding) in persons of both human and non-human form (Brown [Reference Brown and Aveni2015] discusses these topics using primarily ethnographic evidence). These observations underline personhood as being constructed and reinforced over time through ongoing interactions (Fowler Reference Fowler2001:148–149).

Location of Personhood in Non-human Entities

Both of the overviews above—of boundaries and contents of persons, and of action and interaction associated with personhood—indicate that personhood can be located in non-human forms. These forms can be human-like, as in the case of sculptured stelae (Gillespie Reference Gillespie, Borić and Robb2008; Looper Reference Looper2003; Stuart Reference Stuart1996) or clay figurines (Halperin Reference Halperin2014; Hendon Reference Hendon and Harrison-Buck2012); such examples are perhaps most easily recognizable to a Western observer by meeting formal qualities of a human person. In considering carved stone monuments as relational, Looper (Reference Looper2003) has discussed sculpture as animate and possessing power, and O'Neil (Reference O'Neil2010, Reference O'Neil2012, Reference O'Neil, Boldrick, Brubaker and Clay2013) has emphasized the ongoing engagement of sculpture in history, including their continuing changes over time. Such stony sculptural representations engage in relationships and are dynamic, both signs of person-like behaviors.

In Classic Maya contexts, however, non-human persons can include entities that are not human in form—Hendon (Reference Hendon and Harrison-Buck2012:88) cites bowls, jars, and grinding stones, for instance—but are persons in the modes of interaction in which they engage. Houston (Reference Houston2014:98) also talks about vitality in non-human substances in a more abstract vein, identifying stone and trees, for instance, as animate and unified by their warmth and rootedness in the earth. The recognition (on our part) of personhood in non-human entities is part of a larger comprehension of complexities in what it means to be a person, and indicates the need to think critically in Maya contexts about a stance of human exceptionalism, in which human beings are assumed to represent the reference for all types of persons. Hallowell's (Reference Hallowell1960) description of human persons as a subset of a larger category of persons, alongside rock persons and so on, provides an alternate model, in which personhood is not a resource that originates within, or is originally the purview of, human beings.

In sum, Maya research to date has clarified multiple important points about personhood, particularly non-human personhood, in Classic Maya contexts. These studies support the existence of non-human personhood in Classic Maya contexts: entities that are not human beings can act as persons, and be recognized as persons. Previous research has also indicated that there can be close connections between specific humans and non-human entities, with personhood (or parts thereof) passing between the two; this fits with dividual ideas of personhood, in which people are not completely bounded and in which elements may pass between persons (human or not). The relational elements of Classic Maya personhood also suggest that personhood is a contingent and enacted state that can be threatened or undone.

WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO BE FACED?

Before proceeding, we must examine closely a connection that I suggest above, between faces and personhood. Can an examination of depictions of faces aid in understanding personhood? Past Maya scholarship, especially by Houston and Stuart (see below), on the significance of faces and heads provides linkages to support this premise.

Iconographic and epigraphic studies of the Classic Maya head and face indicate that these parts are significant loci of meaning within the human body. The concentrated significance found in the head involves a “complex of meanings revolving around ‘self, person, body, head’” (Houston and Stuart Reference Houston and Stuart1998:76), indicating overlaps between the physical and conceptual elements associated with this body part. Houston and Stuart (Reference Stuart and Houston1998:77) emphasize the “front surface or top of the head” as a physical location for personhood, with “the face or head establish[ing] individual difference and serv[ing] logically as the recipient of reflexive action” (see also Stuart Reference Stuart1996:162), as well as a locus for loss of personal essences, as argued by Duncan and Hofling (Reference Duncan and Andrew Hofling2011). In intriguing comparative ethnographic evidence, the head and face, as “physically or discursively” possessed (Kockelman Reference Kockelman2007:351; emphasis added), is a type of inalienable possession and is identified as a necessary condition for personhood. These discussions provide a foundation for the head as a meaningful seat of “self” and “essential identity” (Houston et al. Reference Houston, Stuart and Taube2006:61) within a Classic Maya ontology. The face in particular seems to play an active role: Houston and Stuart (Reference Stuart and Houston1998:77) emphasize that the face does not simply reflect identity, but rather projects and reproduces it. This active power of faces is underlined in the Classic-era mutilation of faces and eyes on sculptures (Harrison-Buck Reference Harrison-Buck, Iannone, Houk and Schwake2017; Houston et al. Reference Houston, Stuart and Taube2006; O'Neil Reference O'Neil, Boldrick, Brubaker and Clay2013). Stuart's (Reference Stuart1996:160, 162) discussion of the head (baah) characterizes the head not just as a location for the self, but also as a location that links humans and non-humans, especially “figural representations.” This links to another gloss of the word baah connecting to arguments cited above about stelae that represented rulers acting as receptacles into which royal selves were extended, allowing for ongoing activity and discourse on the part of the sculpture.

As noted above, Maya ontologies, both ancient and modern, point towards the social and enacted elements of personhood. Multiple of the relational ways in which personhood is demonstrated center around the head. For instance, Brown's (Reference Brown2000, Reference Brown and Aveni2015) ethnoarchaeological work on Maya object-persons identifies particular activities that serve as indicators of personhood (Brown Reference Brown and Aveni2015:59), several of which—specifically, eating and speaking/communicating—involve the face and facial features (Gillespie Reference Gillespie, Borić and Robb2008:130). Depictions of the mouth may be particularly relevant for personhood: the mouth involves ingestion (e.g., of liquid and solid drinks, as well as tobacco; Houston et al. Reference Houston, Stuart and Taube2006:107), and is a site associated with speech and breath (Houston et al. Reference Houston, Stuart and Taube2006:141, 154). The eyes are also implicated in active relational work: gaze was understood as both projective and receptive (Houston et al. Reference Houston, Stuart and Taube2006:163, 166); having eyes and the ability of sight thus involved a “procreative” (Houston et al. Reference Houston, Stuart and Taube2006:165) power in the world. The act of seeing also connects with witnessing as an “authorizing function” (Houston and Taube Reference Houston and Taube2000:287) in social contexts; the ability of a non-human entity to carry out this important collaborative work indicates its role as an acknowledged and valued community member. In short, the face, and specific parts of the face, is tightly tied up with the types of actions that help an entity to “be” a person; notably, these facial elements and their interactive capabilities indicate the importance of sensory aspects of personhood and of reciprocal ways of relating.

These discussions of the face and head, and the ways in which relational personhood is enacted, indicate that to be faced is to have a location in which personhood may lodge, and to have an interface for relational connections that undergird being a person, as understood by the Maya; the faced objects that I examine in what follows thus have locational and interactive potential as non-human persons. It is this potential to engage in social and relational behaviors that I pursue in the study that follows, rather than specific instances of relational interaction. While the presence of a face seems to be significant as an indicator of multiple elements associated with personhood, there is not a clean one-to-one correspondence: objects with faces are not the sole candidates for personhood. In relying on evidence that supports the face as a physical and conceptual locus for ideas of self and relational connection, I use an intentionally circumscribed frame; the observations that we can make from this study about personhood in non-human entities within Maya contexts may then be extendable to a broader set of non-human persons, including ones without faces, that operated socially and relationally in ancient Maya settings. It is important to stress that the parameters of this study represent a starting point, using human faces as an accessible entry point for iconographically tracing the potential for relationality and building a partial picture of non-human personhood in Maya contexts. In order to avoid the trap of human exceptionalism, it will be important in future work to build on the present findings to identify and track other markers of relationality and personhood.

Finally, a few other possible limitations to this approach should also be noted. While I argue that representations of faces on non-human entities would have been meaningful and understandable to ancient Maya viewers, we do not have evidence of an explicitly articulated category of “faced objects” in Maya writing. Additionally, this study deals with artistic representations, which opens all of the interpretive issues associated with iconographic studies of any type.

DEPICTIONS OF CLASSIC MAYA FACED OBJECTS ON PAINTED CERAMIC VESSELS

In order to explore Classic Maya non-human personhood, I looked carefully at a large dataset of Classic Maya images. I visually analyzed and coded information from 1,047 painted ceramic vessels, as documented in two collections of photographs of such vessels: the Maya Vase database (Kerr Reference Kerr2014) and the Maya Ceramic Archive (housed at Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection). While this combined dataset is not exhaustive in terms of known imagery from Classic-era painted ceramic vessels, it represents a large number of objects created at sites across the Maya world (though also including many unprovenienced vessels); in this sense, my discussion focuses on shared ideas about personhood, rather than specific patterns at distinct sites. We know that some Maya ontological conceptions varied locally, while other logics about the world were more broadly shared (see discussions in Gossen Reference Gossen1994; Jackson Reference Jackson2011; Tedlock Reference Tedlock1982; Vogt Reference Vogt1976); understandings of personhood seem likely to have bridged contrasting political and religious differences that were exhibited across different sites.

These elaborate painted ceramic objects would have been created and used primarily by elites, as serving vessels, drinking vessels, and gifted items (Jackson Reference Jackson2009; Reents-Budet Reference Reents-Budet1994, Reference Reents-Budet, Inomata and Houston2001; see related discussions on Classic Maya writing and its authors and audiences in Houston Reference Houston, Hill Boone and Mignolo1994; Houston and Stuart Reference Houston and Stuart1992). The images painted on such pots thus represent the perspectives of one segment of the Classic Maya population. These images are well suited for addressing questions about faced objects and personhood for several reasons. First, the stylistic genre of these pots is useful for examining a wide variety of objects; in contrast with stelae and many carved stone monuments, painting on vessels tends to be less formal and to feature multiple people and multiple objects, capturing elements of Maya courtly life. Furthermore, I have argued elsewhere (Jackson Reference Jackson2009) that these vessels and the images on them are powerful as depictions of cultural ideals. Representations of faced objects on these pots would have been scrutable to a knowledgeable viewer and, indeed, these images must be understood as oriented towards a specifically located audience (Law et al. Reference Law, Houston, Carter, Zender and Stuart2013:E27). Our inability to securely access the insights that ancient viewers would have had into faced objects means that we cannot know which of the objects in this category were actually faced (i.e., had facial features on their surface) and which were depicted in images as faced, legible to the viewer as memories, extrapolations, or conceptual representations (Jackson Reference Jackson2017). This question about how literally such images can be read is ultimately not as important as recognizing that representations of such objects were meaningful to ancient artists and viewers, as a category that shared certain characteristics.

As I recorded information on these images, I noted all instances in which faces occurred on non-humans (and non-animals/non-plants, allowing for a focus on entities that we typically view as not alive), allowing for the analysis that follows. I have included both humans and supernaturals in my data collection. The observations I make in this article, drawn specifically from the images I examined and the associated data that I recorded, are not exhaustive in terms of all Maya entities shown with faces in the iconographic record.

Within my dataset, which included a total of 3,467 depicted objects, there were 132 faced objects. Faces appear on a range of objects, as seen in Table 1. Among these, some objects are much more commonly depicted as faced (see Table 1), such as masks, seats, handstones, incensarios, and shields. (Due to the large variation in number of instances of each object type, the statistics in the frequency column should be read simply to note that, with the exception of masks, for no object category are all instances of the object faced, and that for most of the categories being faced is a relatively infrequent state.) Note that different types of objects and materials are represented, indicating breadth within this collection of objects and, thus, breadth in the extension of personhood to non-human entities. The objects in Table 1 represent physical diversity in the constituent material (e.g., clay, cloth, and stone), and variation in the size and shape of the object, ranging from small portable objects, such as scepters or masks, to larger and less easily moveable objects like seats and altars. This variety suggests that object personhood is not pegged to particular physical qualities of an object (e.g., an implied requirement that a personhood-eligible object must meet narrow criteria, such as being a hand-held object made of clay). It also indicates that personhood may be transferrable to many types of objects, and that shape, size, and material are not specific barriers to, or, alternatively, requirements for, achieving personhood status.

Table 1. Objects that are shown as faced, including counts and frequency.

We can also notice that there are many objects not depicted with faces (Table 2), if we compare the list of faced objects in Table 1 to the entire universe of objects depicted in scenes on painted ceramic vessels, information I have collected as part of a larger study of objects represented on painted ceramic vessels. Of course, some of the differences between the objects in the two tables are attributable to the datasets, and are not absolute identifications of which objects can or cannot be faced (or, by extension, which are candidates for personhood). One can note, however, that there is a relatively large and diverse set of categories of objects, 65 total, depicted in scenes on painted ceramic vessels (a number that could be even larger, depending on how categories of objects are subdivided, or not). Only 15 of these (approximately 23 percent), however, are shown with faces. Thus, not all, or even most, objects are ever shown with faces: there is a more limited subset of objects that are depicted in this manner. This is a state of meaningful differentiation entered into by certain objects.

Table 2. Objects not shown as faced in the dataset. The following objects are ones that are depicted in the dataset of painted ceramic vessels that was examined for this study, but are never depicted as faced within this dataset.

LINKAGES BETWEEN HUMAN FACES AND FACED OBJECTS

We next need to look carefully at how these faced objects relate to humans. To better understand this relationship and, by extension, some of the nuances of personhood located outside of human contexts, the following section examines how faces on objects manifest in different examples.

Faced Objects Reference Human Bodies

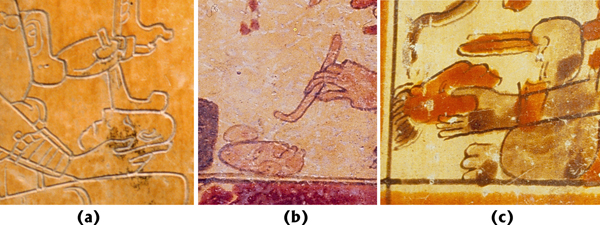

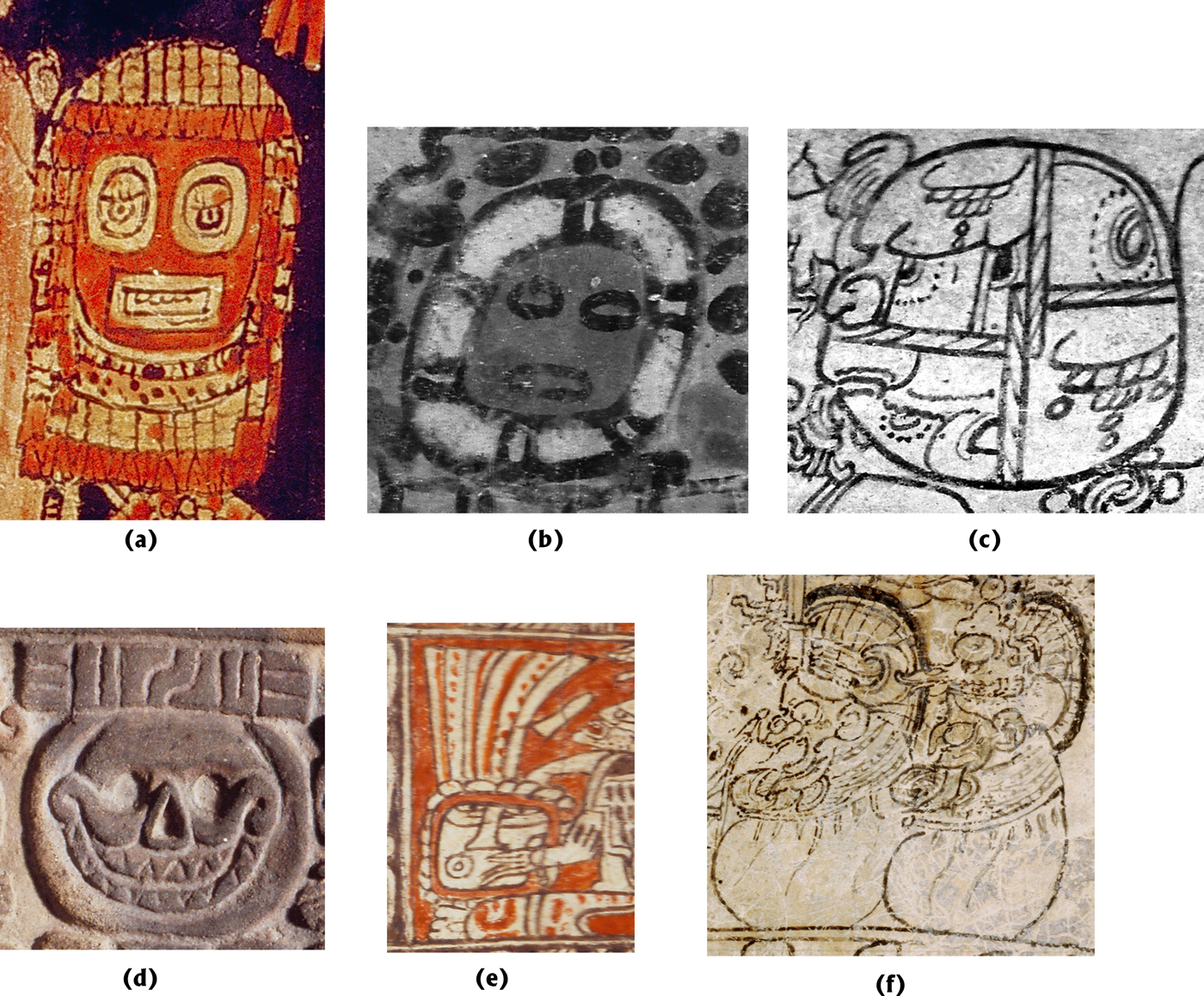

Multiple examples of faced objects demonstrate that their faces can originate directly from physical human bodies, thus explicitly indexing human beings. Examples of depictions of balls, shields, and bundles provide clear examples of this phenomenon (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Shields, balls, and bundles as examples of faced objects that originate directly from the human body: (a) K2695, (b) K4685, (c) K4118, (d) K5201, (e) K5384, and (f) K7838. Photographs © Justin Kerr (Kerr Reference Kerr2014), reproduced with permission.

When shields are depicted with facial features, they are shown as being made of flayed human facial skin (Houston et al. Reference Houston, Stuart and Taube2006:21; Schele and Mathews Reference Schele and Mathews1979:71). The linkage in this case is very direct: human skin removed from the face is stretched and dried to create these objects. This involves literal transference of a human face to a non-human object. While some shields were likely made of human skin, not all would have been, and as noted above, we might not interpret all shields that are depicted as faced as literally made of facial skin. Rather, recalling the positionality of the intended viewers of these images, such depictions might be understood as references to a prototypical version of a shield, which would have directly linked a human body and the faced object.

Balls are another type of faced object that originates in human bodies, specifically, the human skull. The referent for faced balls, and the symbolic connection for balls in ball games more generally, is the Popol Vuh story, in which the head of one of the Hero Twins is used as a ball in the ball game played with underworld lords (Tedlock Reference Tedlock1996). In the dataset I examined, faced balls are shown both as de-fleshed, skull-like images (e.g., K5201) and as living heads (e.g., K4118, K6064, and K9265; see contrasts in Figure 1). These faced balls seem to be non-literal references that evoke a prototype, and mark the status or capability of the object, since rubber balls seem to have been used for Classic-era ball game rather than actual human skulls (e.g., Scarborough and Wilcox Reference Scarborough, Wilcox, Scarborough and Wilcox1991). These examples indicate that objects that are depicted as faced can illustrate a conceptual category of faced (and personed) status for objects.

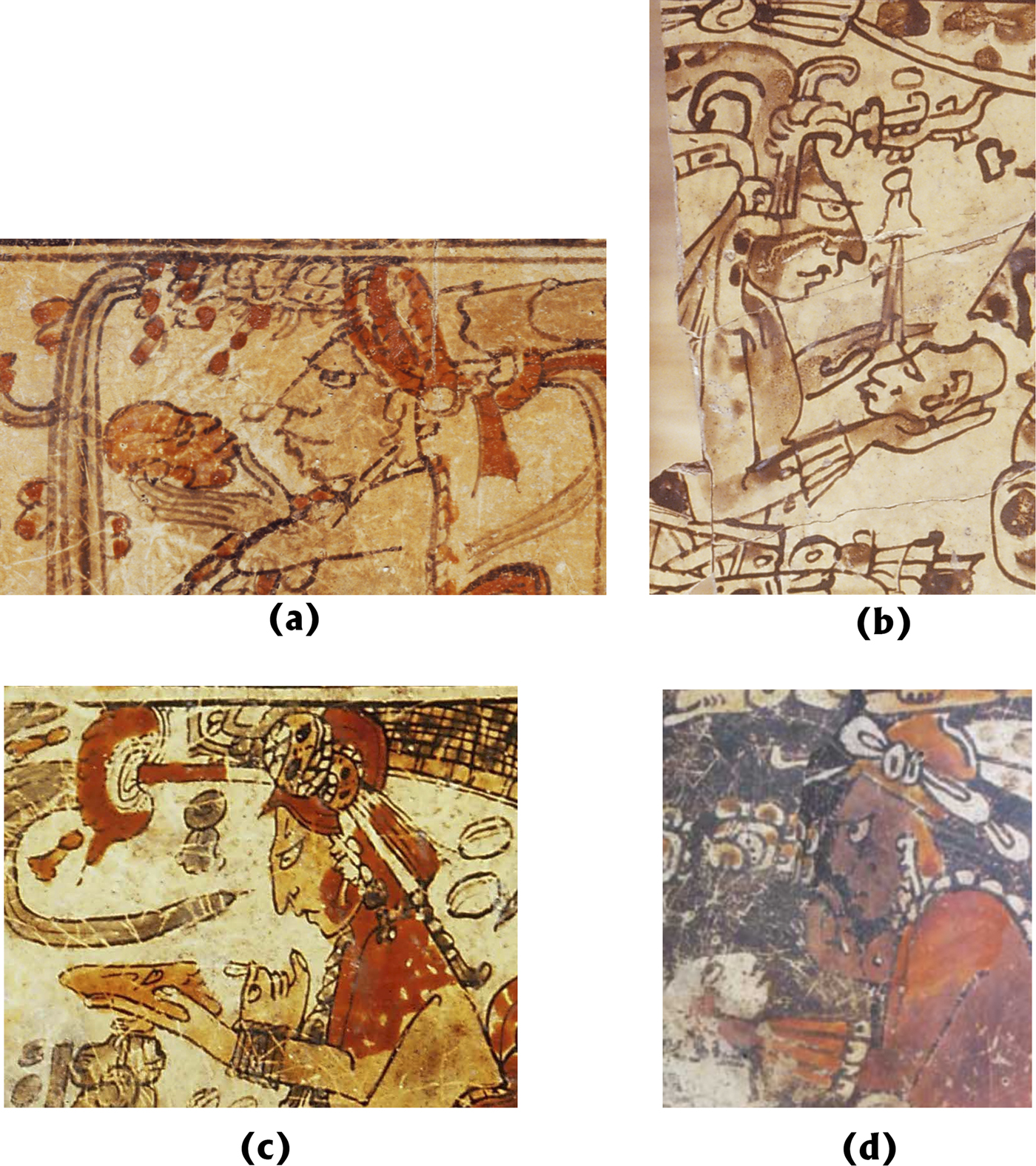

Some examples of bundles (e.g., K4485) also directly link to human faces and bodies, as seen in depictions of faced bundles as wrapped bodies with visible heads. These bundles seem likely to be representations of secondary burials (a recognized burial practice in the Maya area [e.g., Fitzsimmons Reference Fitzsimmons2009:76–80]), and thus are directly indexical in their relationship to the human body. The faces shown can be parsed as masks that are adhered to bundled human remains, or as actual heads emerging from the remains within the bundle; the faces on these bundles are shown as supernatural rather than human, raising questions about whether human versus supernatural faces shown on faced objects represent a difference in the meaning or nature of personhood in non-human contexts. While the face is emphasized, in comparison with the shield and ball examples above, these instances imply the involvement of a more complete body in personed objects. This observation should give us pause: are these bundles examples of faced objects, or is this a category error on our part, and these are not objects, but rather humans (or something in between)? This question points out some of our discomfort with fuzziness in the boundaries of these categories, and problems with translation of categories. While a burial is (or was) a human being, we have hints (e.g., the separation and/or dislocation of body parts through revisiting, the movement of bodies to secondary burials) that bodies can transition into different material statuses. Indeed, the faced bundles shown occupy a liminal space in these images, seated on benches in places that might typically be occupied by humans or by material offerings.

Representations of bundles require some additional examination, as not all faced bundles are represented in the same way. In some cases (e.g., as shown in six instances from a single vessel, K5384), bundles can be shown in a standard round style, coupled with other typical offering items. Compared to the “bodied” bundles described above, these faced bundles present as round heads, with eyes, nose, and sometimes mouth shown on the rounded surface of the bundle. These seem less likely to represent bundle burials. Ritual bundles, known through ethnographic, archaeological, and iconographic contexts (e.g., Guernsey and Reilly Reference Guernsey and Kent Reilly2006), do not always contain human remains, but nonetheless are considered animate entities (Brown Reference Brown and Aveni2015:53): the second type of faced bundle could represent this type of object. The two types of faced bundles, one of which seems to connect directly to deceased human bodies, the other of which seems to lack a direct connection to a referential human body, demonstrate that previously apparent human-object connections may be lost or may recede, but the face and personed status of the object can still endure.

For shields and balls, we see that a face can be transposed or translated from a human body to a non-human entity. In the case of shields, the face is lifted from a human context and adhered to an object. In the case of balls, we see a partition—actual, and then subsequently referenced—of a human body that allows for a human face to subsequently operate as an object. Faced bundles seem to indicate that even whole human bodies might cross boundaries in becoming objects. These instances indicate that faces—and personhood—can physically originate from humans, and can then move; that is, a face does not have to be attached to a human body in order to be meaningful. For these examples, it seems that the faces on faced objects point back directly to human beings, as a referential locus, though we must ask whether this is always the case for faced objects. Having identified this linkage, we should also ask: must personhood be linked directly to a specific human source? That is, what kind of resource is it? The successful movement of a face from a human to an object also raises questions about what the resulting capabilities are: does the face (as one indicator of personhood) indeed continue to operate in its object context? In what ways are objects changed by entering into a faced status?

Do Faced Objects Require Humans?

Above, we identified that faced objects can have a strong and direct connection with human bodies. These examples beg the question: do the faces on objects always derive directly from a human body? The simple answer is: they do not. Many instances (e.g., masks, seats, and handstones) show faced objects that are neither physically taken from a human body nor directly linked to a specific human body; nor do these examples seem to invoke a specific memory or prototype that would have been human-derived. Instead of relying on a direct connection, we see that person-ness can be invoked without a one-to-one link or correspondence. This opens the door in terms of the materials or objects in which we may see personhood, and the circumstances in which object personhood may be possible.

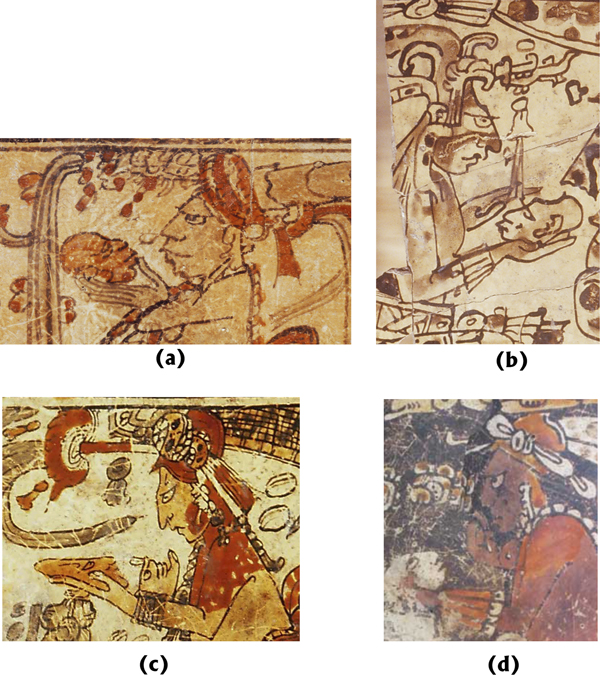

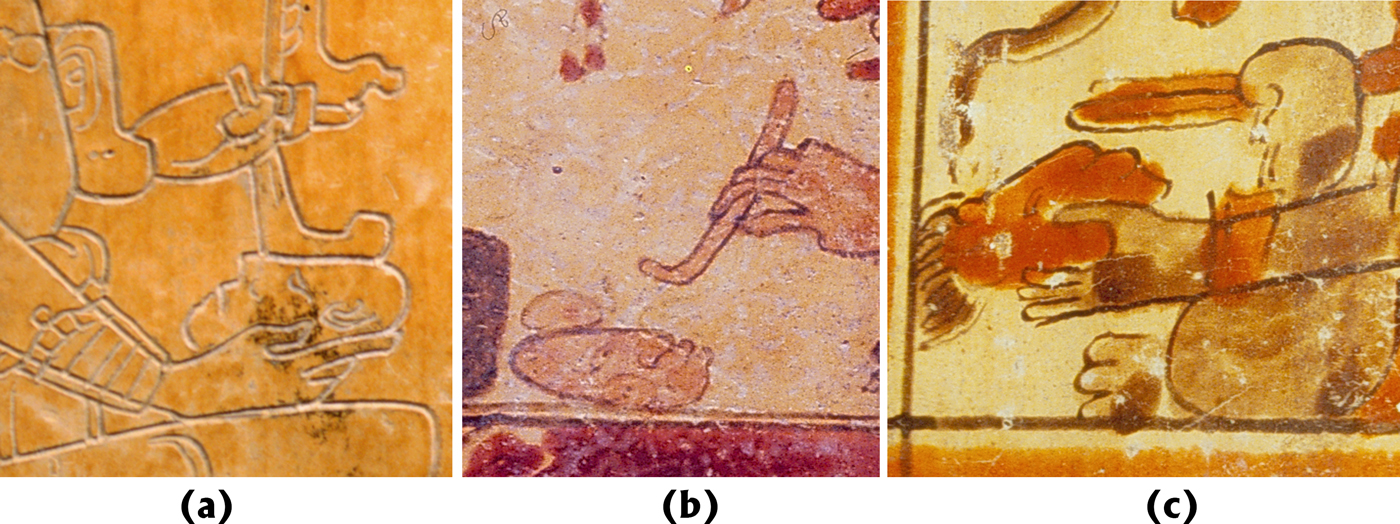

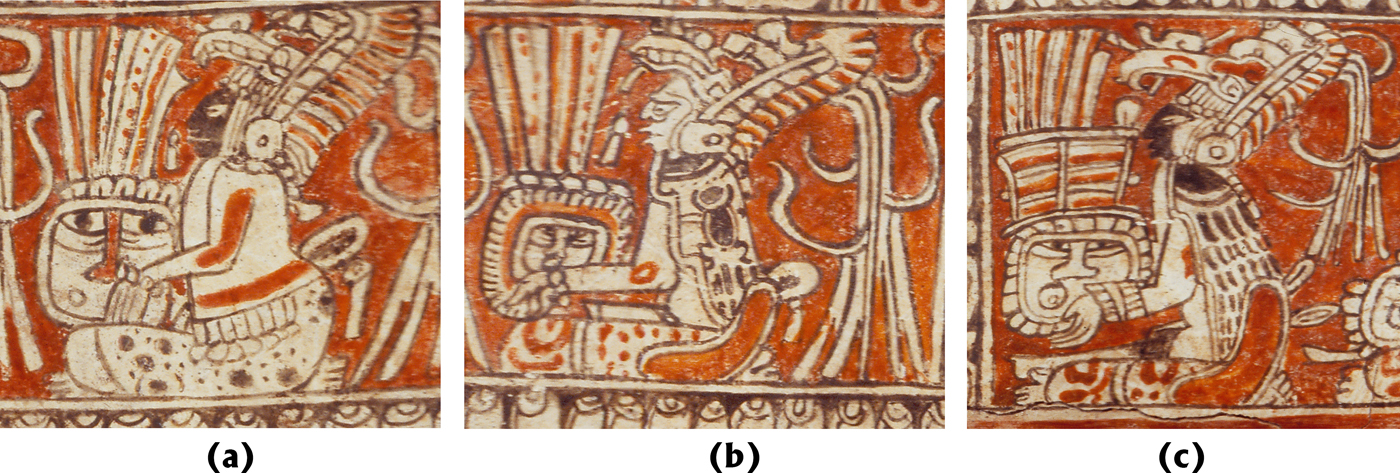

Not only do faced objects not have to come from a human body, some examples indicate that faces can actually be created from raw materials. Let us look for a moment at the most common of the faced objects: masks. As functional objects, masks, of course, represent visages; they also are granted close proximate access to human bodies by being layered over the face. Their functionally faced nature does not, however, discount them as “faced objects” in the sense of being candidates for person status. Mask usage has a long history in Mesoamerica (e.g., Markman and Markman Reference Markman and Markman1989), connected to ideas about masks’ active abilities to transform and impart identities. Depictions of masks, as shown in the painted vessel genre, represent the process of creation, with multiple examples showing active carving of masks (Figure 2). This may be in part a result of the courtly, indoor representations shown on these vessels, indicating that carving is an activity that would have occurred in these spaces, but for our purposes it indicates that faces and faced objects can sometimes be made, and that such acts of creation are in fact visually emphasized in some cases. This is also important because it means that there is not a one-to-one correspondence between humans and personed objects. In a broader sense, it means that the resource of personhood is not a limited one: it can be renewed, created, disseminated.

Figure 2. Masks represent faced objects that can be made or created; note the carving tool held in the hand in each example: (a) K8820, (b) K1836, and (c) K6061. Photographs © Justin Kerr (Kerr Reference Kerr2014), reproduced with permission.

What can we conclude for other objects that do not show a direct connection to humans, and whose faces are not specifically depicted as being “made” (e.g., objects like baskets or pots, handstones, and incensarios)? Is human intervention or input needed for an object to become faced, or personed? That is, are humans required for objects to be faced (and personed), even if the face (and person status) does not have to move directly between a specific person and an object? Or, could the acquisition of a face and of personhood for objects occur apart from human action, intervention, or contribution? Faced objects are typically shown in conjunction with humans, not solo, but this may be due to the types of scenes depicted on ceramic vessels. Multiple object categories noted above are neither shown as made nor as directly drawn from a human body (Table 3) and thus may be candidates for independent manifestation of personhood.

Table 3. Types of faced objects that do not derive directly from the human body, and that are not explicitly shown being made

These examples illustrate that faces on objects, and thus personhood, do not have to have a one-to-one correspondence with human bodies (i.e., they may not derive from a specific human body), and are not a limited resource—they can be created (e.g., carved or formed out of raw materials) from a larger pool of personhood. We see that object faces exist and persist outside of specific human linkages or sources.

Faces Continue to Function

Above, I wondered about the capabilities of a face on an object. Specifically, does the face, as a personhood marker, function in its object context? Or, is it a category marker without specific abilities?

If we examine the contexts of faced objects, we recognize examples of bodily needs and social interactions underscoring the enacted and relational nature of their personhood. We see several types of social interactions between human bodies and objects in the images under examination: caretaking through dress and physical touch, conversing, and feeding.

Object care is seen through the wrapping of objects, which serves to dress them, and also through touch and caress of these objects. Both types of bundles discussed are wrapped (for discussions of wrapping, see, for example, Houston and Stuart Reference Houston and Stuart1998:78; Houston et al. Reference Houston, Stuart and Taube2006:84; Stuart Reference Stuart1996:156). This wrapping, in addition to being a key part of the structure of bundles, is a type of dressing and is one of the signals of being treated in a person-like way. Other objects have cloth or bindings tied to them, as an alternative type of “dress” (e.g., the faced ball on K4118). Additionally, Scheper Hughes (Reference Scheper Hughes2016) suggests cradling as a long-term Mesoamerican mode of looking after and caring for objects, and another signal of objects being tended to. Images of faced bundles (Figure 3), for instance, are shown in profile, and cradled by the hands and between the forearms of the humans depicted.

Figure 3. (a–c) Examples of repeated motif of cradled bundles on K5384. Photographs © Justin Kerr (Kerr Reference Kerr2014), reproduced with permission.

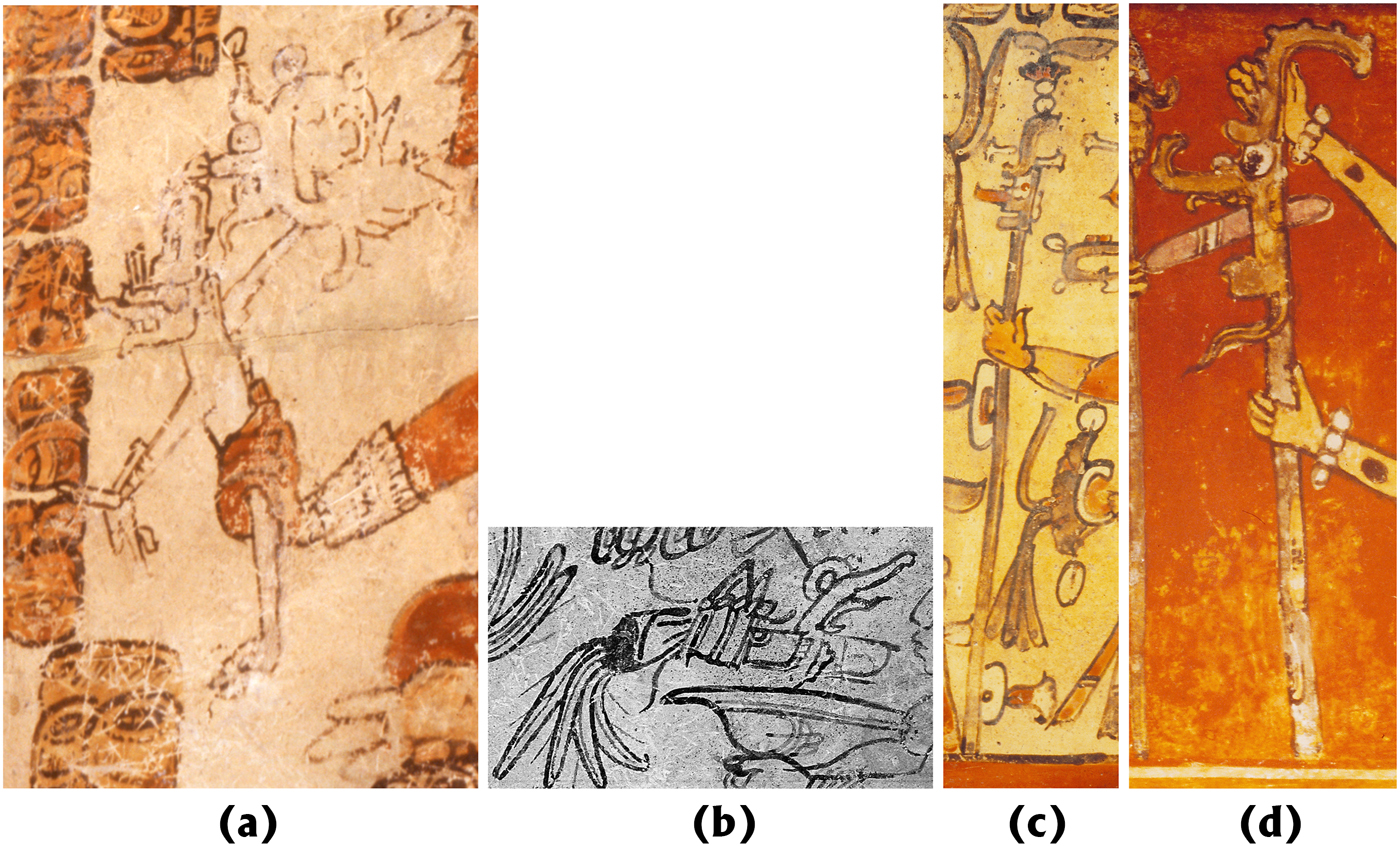

Other objects that are frequently touched and held carefully in the hands include masks, showing physical closeness and skin-to-skin contact. Furthermore, the face-to-face (even, nose-to-nose) orientation of many masks orients the faced mask in implied conversation with human faces (Figure 4). Other faced objects can be seen as communicating through their exhalations, as is the case with censers; the smoke that emerged from such objects was understood as message-laden (e.g., Stuart Reference Stuart and Houston1998).

Figure 4. Masks being touched and engaging in implied conversation: (a) K5373, (b) K8457, (c) K7447, and (d) K9096. Photographs © Justin Kerr (Kerr Reference Kerr2014), reproduced with permission.

The exhalations or emissions of censers are also tied to their ability to ingest—that is, to consume and to eat, another hallmark of a person and person-like needs. Ethnographically, we are aware of incensarios’ (or god pots’) need to be fed (e.g., McGee Reference McGee1990:52); iconographically, we see this shown through the balls of copal or incense they are fed (albeit at the top of the head rather than in the mouth), coupled with smoky exhalations (again, through the top of the head; e.g., Houston and Taube Reference Houston and Taube2000). In this way, the burning of incense represents human-like needs/actions of input and output, consumption and exhalation. The presence of a mouth that we see here, and the associated processes of breathing and consumption, can also be thought of as being writ large on temples and their related landscape counterparts of caves (see discussion in Houston and Taube Reference Houston and Taube2000), pointing out that “object personhood” may be an unnecessarily limited descriptive category, with personhood manifesting in the built (not to mention natural) environment, as well.

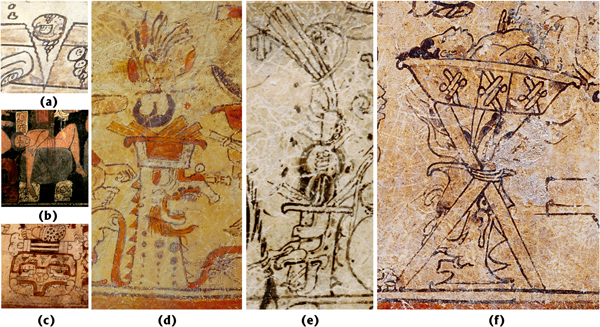

Paying attention to social aspects of personed objects and their bodily needs raises an interesting conundrum for an article about faces: objects that are faced might better be understood as being embodied. I do not use the term “embodied” in a broad sense here; rather, I am referring to the possession of a body. In looking at the suite of faced objects, some actually seem to have bodies. These objects include bloodletters, staffs, scepters, and axes (Figure 5). The depictions of these items are similar, in that they each have a slender, elongated element of varying lengths as their main segment, with the face/head attached to it. These linear elements act in a body-like fashion by supporting the head like a neck and vertebral column. For the most part, these pole-like implied bodies are not further elaborated, with the exception of k'awil’s foot (e.g., in K8719) marking the lower extremity of the body in some scepter representations (e.g., Stone and Zender Reference Stone and Zender2011:48–49). These examples of heads and faces attached to body-like elements contrast with most of the previous ones, in which faces are applied to the form of objects, or heads stand alone like a severed or separated body part. These “attached” examples indicate that faces and heads are, ultimately, connected to bodies.

Figure 5. Faced objects with “bodies”: (a) K8719, (b) K1362, (c) K6649, and (d) K9073. Photographs © Justin Kerr (Kerr Reference Kerr2014), reproduced with permission.

These examples may indicate that when we see faces they are functioning synecdochically for an entire body; that is, faced objects—even those, the majority, that only show facial features—are referencing and implying an entire corpus, one that engages in bodily functions and has bodily needs. Faced objects are, in fact, embodied objects, and function in the ways we would expect for a living entity with a head and body.

Faced Objects Retain Elements of their Material Nature

In the preceding discussion of objects as embodied, we see faced objects not just looking like people but also acting like people. We might be tempted to think of faced, and personed, objects as simulacra of humans in their needs and capabilities. It does seem clear that objects are changed by entering into a state of personhood, through their relational needs and capabilities. Critically, however, depictions of faced objects indicate that they do not cease to be objects; they retain both base material properties and functions even as they become personed.

Depictions of faced handstones help to illustrate these points. First, we can observe that their function is sustained, even when they are faced. Handstones were used in the ballgame, and—as their name indicates—were made of stone and held in the hand (Borhegyi Reference Borhegyi and Lothrop1961). These handstones are shown as being very active—their mouths are open, they are grasped, touched, and moved around. The implied action of these handstones relates to their object nature: these are weapons used in hand-to-hand combat, and they continue to function as such in their personed aspect. That is, they do not discard their functional elements upon becoming faced. Additionally, in many cases faced handstones are visually marked as stony with a “stony” Maya property qualifier, a glyph-like visual marking that signals material affiliation (see discussion of property qualifiers in Houston et al. Reference Houston, Brittenham, Mesick, Tokovinine and Warinner2009; Jackson Reference Jackson2017; Stone and Zender Reference Stone and Zender2011). The stony property qualifier indicates a quality of the base material of the handstone. This is significant because it shows us that these objects, even when they become faced, retain essential elements of their object material identity. That is, an object-person does not cease to have elements of its object identity; rather, it combines elements of person-ness and object-ness. This indicates the possibility of co-existence of these two states: these are stony, person-like figures.

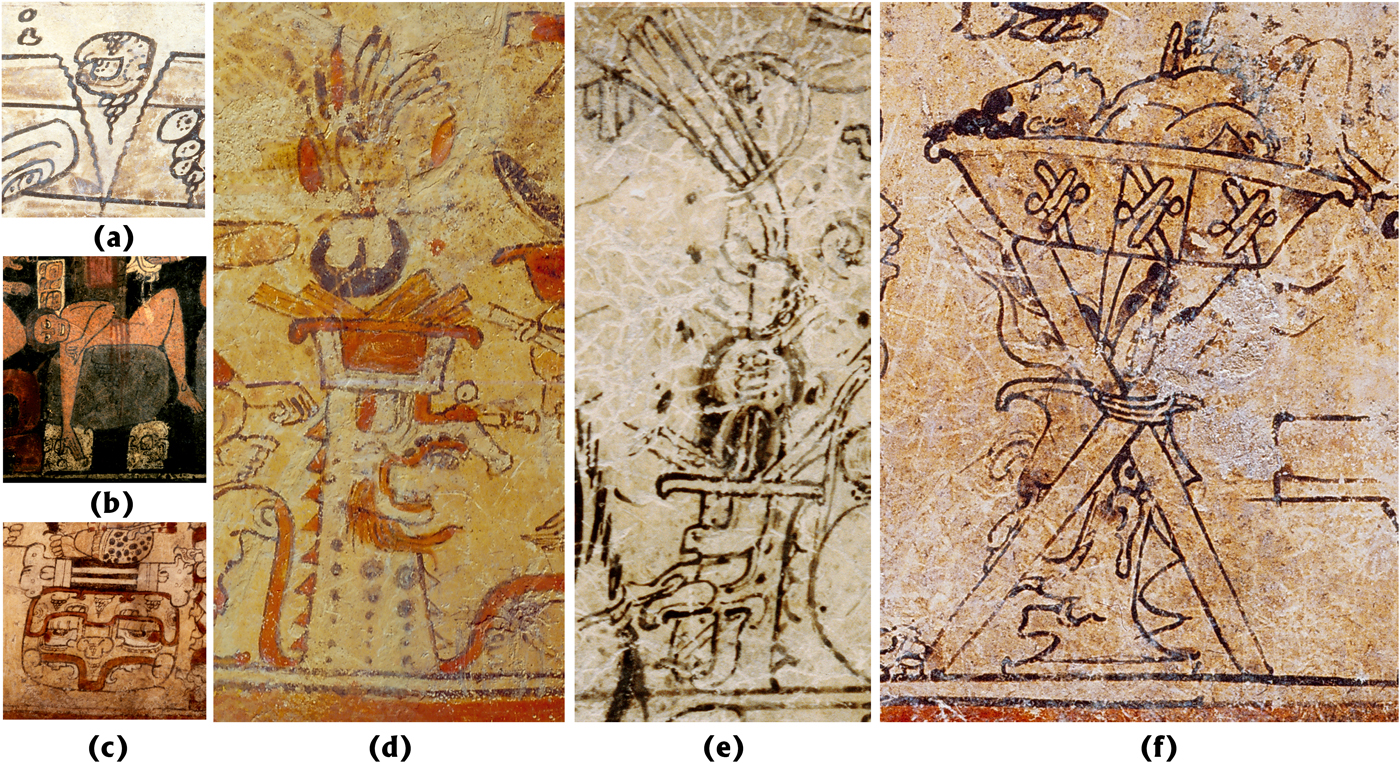

Stones, altars, and seats (Figure 6) are other faced objects that provide examples of objects explicitly retaining their function and material qualities when personed. They are often marked with stony markings, and they continue with their functions of cutting, supporting, and receiving offerings. Faced pots and baskets also retain their essential functioning: in each instance of a faced vessel, the pot or basket is shown containing something (e.g., a mask or shells), functioning in the same way that non-faced pots and baskets do, and confirming that the faced receptacle is able to continue to do its work in the expected manner.

Figure 6. Stones, altars, and seats retaining material qualities and object functions: (a) K2068, (b) K8351, and (c) K5847. Faced ceiba incensarios showing the layering of multiple qualities: (d) K5113, (e) K7838, and (f) K1645. Photographs © Justin Kerr (Kerr Reference Kerr2014), reproduced with permission.

We have noticed that objects can retain their material qualities even when becoming faced. Depictions of faced incensarios (Figure 6) include material markers that further layer our understanding of the multiple categories to which faced objects can belong. Multiple depictions of faced incense burners show “ceiba incensarios,” known from archaeological contexts (e.g., Zidar and Elisens Reference Zidar and Elisens2009) and intended to imitate the spiny bumps of the ceiba tree, a cosmologically important axis mundi for the Maya. This is intriguing because these faced incensarios illustrate objects inhabiting additional material domains: we have a clay, incense-burning object that is referencing both tree-qualities and person-qualities. We know from examples above that qualities can coexist (e.g., the handstones are still stony, and still act as ballgame implements, even while faced/personed). The incensario example pushes this further, as these objects are doing multiple types of simultaneous referential work (tree, person). This suggests that the multifaceted state that faced objects can inhabit, accompanied by the associated needs and capabilities, can include multiple components, and that the unstable person/object categories that emerge through the discussion in this article might be joined by porous boundaries between other apparent object or material categories, as well. While this article has focused on how personhood as a state can be extended to and experienced by both humans and objects, close examination of other categories, and the relational broaching thereof, will be productive in elucidating other elements of Classic Maya ontologies.

CONCLUSIONS

This study took an intentionally narrow focus—looking at faces depicted on objects in Classic Maya contexts—as a way of examining a specific environment in which objects show markers of being personed. These examples were thus examined in order to see how these objects become personed and the impacts of the adoption of a person-status. While the specific findings aid in understandings of Classic Maya contexts, the areas of inquiry may prove more broadly useful by indicating some complexities within systems of partible personhood.

This investigation revealed several things related to understandings of personhood for the Classic Maya. Examination of faces, heads, and their significance has indicated that the presence of faces in non-human contexts in Classic Maya iconography can serve as a useful proxy for the presence of personhood, imbuing the faced object with certain person-like qualities, including needs, abilities, and social qualities. Examination of both tight and looser linkages between faced objects and human bodies shows that, while some faces on objects can come directly from human beings, a one-to-one correspondence or translation between human and object is not required. While object faces reference human ones, they do not have to have a specific, identifiable human referent, and can be created from scratch (e.g., carved or otherwise made). In some ways, this reflects the ways that dividual personhood has been observed to work in other contexts: elements move between persons (human or non-human), and can be absorbed or incorporated into the recipient. While some examples above show movement of personhood (or elements thereof) from a specific human person to a non-human person, other examples indicate that non-human persons can receive a status of personhood from a resource reservoir that is not connected to a specific human being. This points towards personhood as a resource that is accessed by humans and non-humans alike, following Hallowell's (Reference Hallowell1960) comments about the alikeness of all persons, and echoing the idea underlying Viveiros de Castro's (Reference Viveiros de Castro2004:466) description of an Amerindian perspective that “presumes a spiritual unity and a corporeal diversity”, and may indicate ways that personhood should be characterized as separable or untethered or neutrally located in this cultural context, avoiding some of the anthropocentric assumptions that may accompany the “partible” designation. For the Classic Maya, being a person for any entity involved acting and relating in ways that allowed access to the resource of personhood. This latter point is important: personhood is not automatically obtained, nor does my characterization of a neutrally locally resource reservoir suggest that this is a source that is passively drawn from. Rather, the network of relationality, of connections between various relational beings, not just other humans, provides the route to this resource. For instance, we can think of comparative discussion of the enacted and relational processes involving both humans and objects that transform Aztec infants into persons over time (Eberl Reference Eberl2013; Furst Reference Furst1995; Joyce Reference Joyce2000b). Conversely, a lack of relational engagement cuts off entities from their relational status and moves them out of a state of personhood. The observation in this study of both non-human persons who seem to link directly to human beings in terms of the source of their personhood and also those who do not might be understood, not as fundamental differences in the source of personhood but, rather, as intriguing differences in the route or conduit that personhood takes in moving within a relational model. These observations also point to the necessity of future expansion of work on this topic that does not rely on human-aligned markers (e.g., the depictions of faces I used for the present analysis) in order to more completely represent the apparent non-anthropocentric elements of personhood.

Additionally, the examples discussed above indicate that person-like qualities found in faced (or personed) objects do not cancel out essential elements of objects’ material or functional natures in Classic Maya understandings. Rather, non-human persons enter into a state that includes both person and object elements. We anticipate, per Strathern's (Reference Strathern1988) ideas about dividual personhood, that some combination of elements may occur in the incorporation of particles between persons (see Busby Reference Busby1997 for discussion of different models); Duncan and Schwarz (Reference Duncan, Schwarz, Osterholtz, Baustian and Martin2014:151) use the term “mosaic corporeality” to express the burial situations that they witness in Maya contexts, emphasizing that elements co-exist but are not blended. Monaghan's (Reference Monaghan1998:141–144) discussion of co-essences evokes a sense of linkages between distinct, even autonomous, entities (not simply humans and animals), though his emphasis on destiny and connection from birth implies long-term stability to these connections that may not represent the contextual and changeable nature of multiple category states. The challenge here is to describe the simultaneous co-existence of whole things (e.g., person-ness, object-ness) that relate and influence each other, and that may cohabit within the same form, but do not lose their essential identities in that co-existence, without resorting to immobile descriptive dichotomies or binaries (per critiques and observations in Bird-David Reference Bird-David1999; Harris and Robb Reference Harris and Robb2012; Viveiros de Castro Reference Viveiros de Castro2004; Webmoor and Witmore Reference Webmoor and Witmore2008; Wilkinson Reference Wilkinson2017). An object person is both an object and a person and, perhaps, other things, too (at least some of the time). Nevertheless, are characterizations like the admittedly clumsy descriptor “object person” still encoding Western-based binaries and our own commitment to reinforcing differences between persons and objects? We need to continue to plumb the nature and experience of human cohabitation with other entities in Maya understandings.

We might ask what other things human beings might be besides persons, and whether a keener awareness of the multiple inhabitation of such states could aid in clearer understanding of differential human identities and experiences. Fowler's (2016) incisive comments about the necessity of engaging multiple axes in considering relational personhood resonate with these ideas. This is also an area in which future work will need to push beyond the category of “objects” to include other entities outside of the scope of the current dataset that seem to meet criteria of livelihood and animacy (including the possession of faces); the built environment and the natural landscape (themselves interconnected in terms of categories and references) are particularly ripe areas for this further investigation. Certainly, ethnographic clues explicitly point towards the possibility of personhood residing within the landscape. For instance, Q'eqchi’ descriptions characterize mountains as living, and having the quality of wiinqilal, or personhood (Wilson Reference Wilson1995:53); additionally, iconographic cues suggest the presence of bodily (not just facial) elements in the landscape, per observations by Coltman (Reference Coltman2014:49) on the fleshy and fatty substance of mountains, places that are also framed as wombs—clearly connected to aliveness.

The discussion in this article also indicates some unresolved issues related to object personhood. This study was topically narrow, and one must consider to what extent these observations can be generalized. For instance, in Maya iconography, faced objects are occasional occurrences for certain types of objects (e.g., shields and pots). How should this specificity be interpreted? It may relate to the genre of images depicted on these media: specific episodes related to particular persons and associated objects. What about the instances in which those types of objects are depicted without faces? More research is needed to clarify the extent to which object-personhood for a particular object is a special state, or to what extent it has the potential to manifest, generally, in other objects of that type. I am struck by observations made by Harris and Robb ([Reference Harris and Robb2012:670] in considering the question of whether shamans “really” transform into reindeer) about the significance of potentiality in engaging with an animated world, and the possibilities unlocked by interacting with materials through multiple modes. Following these observations about a multifaceted nature of interacting with the world (e.g., objects do not have to be strictly animate or inanimate in a binary fashion), my instinct is that object-personhood is a non-quotidian status for the Classic Maya—that is, just because one shield may be indicated as an object person does not mean that all shields would generally have held this status. The social and enacted qualities of personhood mean that it would have been contingent and possible, but not a steady state. Therefore, we must better understand the lability of the state of object-personhood. Kockelman (Reference Kockelman2007:352) suggests, for instance, the necessity of adopting a historical or biographical stance towards inalienable possessions that are implicated in construction of personhood in order to understand the ways in which they change over time. In Classic contexts, can we track object-persons moving in and out of an activated state? This dynamic nature points towards the necessity of understanding more about contextual contingency: what are the circumstances (e.g., setting, co-participants, and environmental factors) in which personhood is likely to manifest? Can one pinpoint contextual elements that seem to engender personhood or, alternatively, could an understanding of the necessary contexts help identify previously unidentified instances of personhood? This would add further nuance to our awareness of relational activities that would impact the possibility of personhood. This could also then allow for investigation of personed objects that are not explicitly shown with faces, moving beyond some of the limitations of using presence/absence as an indicator, and illuminating the multiple factors that explain, or necessitate, the presence of personhood in particular instances; attention to context may also help illuminate the varied routes to personhood mentioned above. Examining non-faced objects and depictions of faced and unfaced objects in other genres will be important, as will looking at visual substitutions in contrasting environments and contexts. Finally, the discussion here has elided human/supernatural differences indicated in the faces that appear on objects, suggesting the need to consider the possibility of different types of persons, as we continue to explore the edges and location of personhood in Classic Maya contexts.

RESUMEN

Las investigaciones sobre la personeidad de los mayas del período clásico indican que la personeidad se extendió a entidades no-humanas; sin embargo, quedan preguntas sobre su funcionamiento e impacto. ¿Cuál es la naturaleza del vínculo entre los seres humanos y las personas-objeto, y cómo pasa la personeidad entre ellos? ¿Cuál es el impacto de convertirse en persona para un objeto? Este artículo examina estas preguntas a través de representaciones de rostros en objetos no humanos en la iconografía maya clásica, indicando su potencial para funcionar como personas. El examen de los objetos con rostros revela que la sustancia de la personeidad maya clásica; no requiere a los seres humanos como fuente, y actúa como un recurso sin conexión de todas las entidades con capacidad de actuar en manera social y relacional. Además, la personeidad en objectos representa un estado de identidad en el que coexisten las esencias de personas y objetos, abriendo posibilidades para complicar categorías de ser en el antiguo mundo maya.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work has benefited in profound ways from ongoing conversations with my valued collaborator and dear friend, Dr. Linda Brown. Many thanks to her for inspiration, pointed questions, and useful insights. Thanks also to my colleague, Dr. Vernon Scarborough, who is a generous and incisive early reader of my work. I am deeply grateful to Justin Kerr, not only for the permission to use his beautiful images, but also for making available such a rich corpus of work through his website. Much of the work described in this article was carried out while on sabbatical from the University of Cincinnati, and while supported by a Taft Center Summer Research Fellowship. I also want to express gratitude to Dumbarton Oaks and the staff of the Pre-Columbian program for facilitating my access to the Hellmuth Maya Ceramic Archive collection of images, which I first examined as a Junior Fellow there years ago. Three anonymous reviewers provided detailed and insightful critiques that have improved this article and its argument in ways large and small: I am grateful for their comments. Any shortcomings or errors are mine alone.