“ENCLOSURES WITH INCLUSION”—AS BOTH A METAPHOR AND A SOCIAL REALITY

This article proposes that what will be named here “enclosures with inclusion,” which functioned both as a metaphor and a social reality, substituted, in effect, physical, geographical, as well as social boundaries, in pre-Aztec and Aztec central Mexico, well up to the coming of the Spaniards. It will be argued further that the role of such social enclosures was not to segregate, but rather, to accommodate incoming groups and peoples.

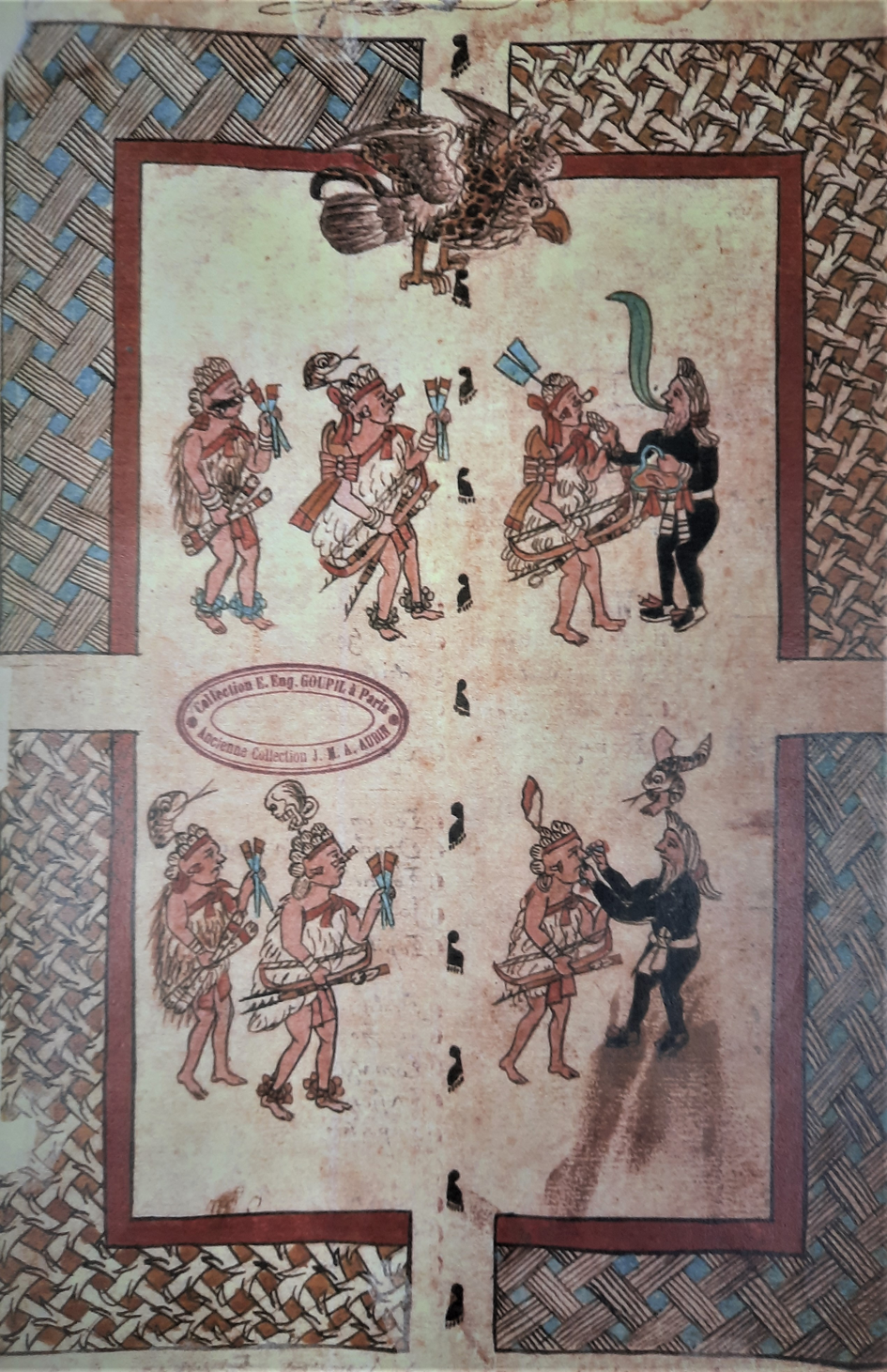

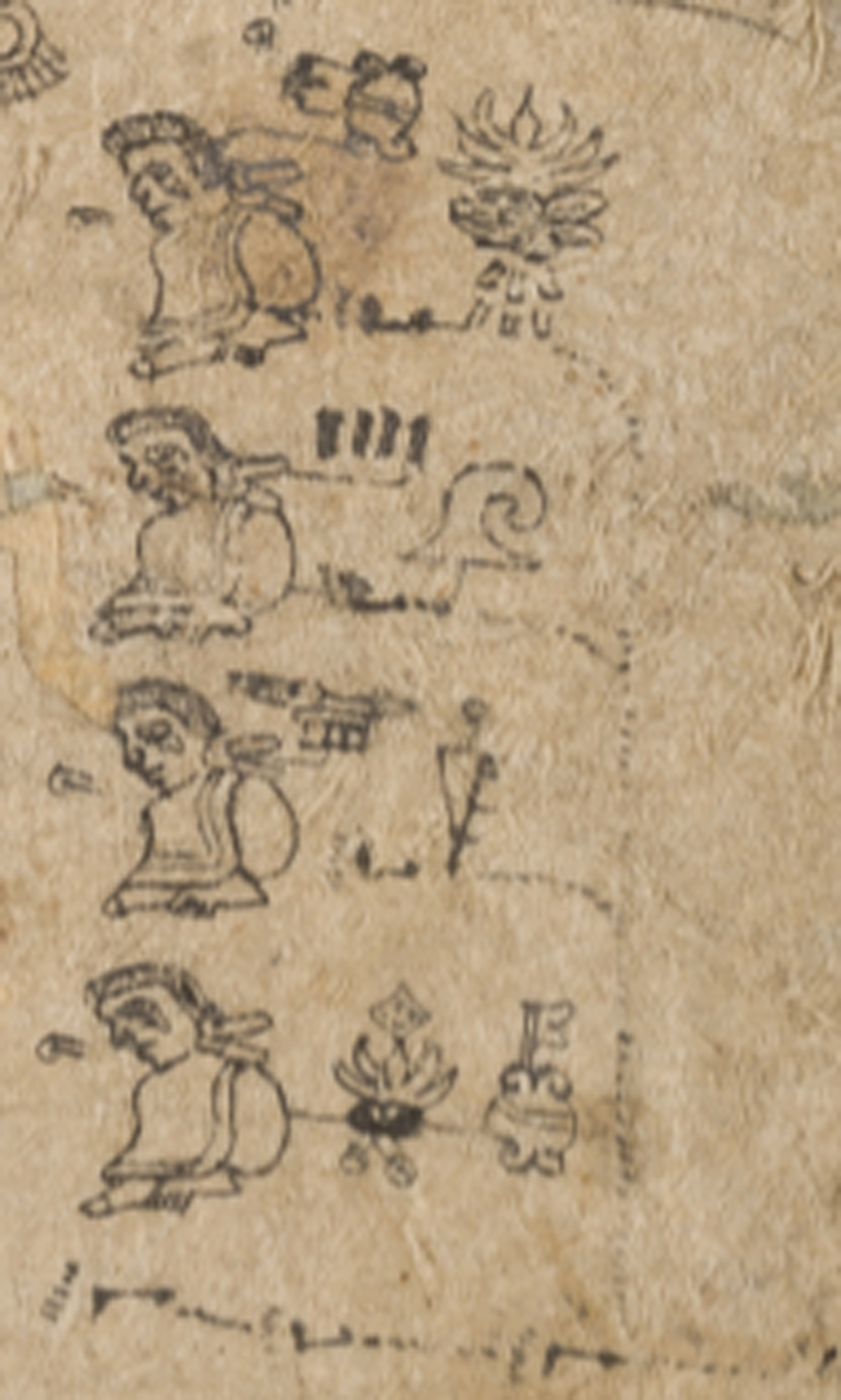

On folio 21r of the Historia Tolteca-Chichimeca manuscript (Figure 1), braided edges frame the entire scene, a sacred precinct in the form of an enclosure made by a woven mat in different textures. Above the scene we see the image of a sizable vulture, which may well represent Cuauhtinchan's toponym. There are footprints entering the framed scene from the opening on the upper part of the frame, toward the bottom part, where they are seen leaving the frame through an opening. The footsteps could signify the passage of a procession entering and exiting what is observed as a sacred ritual precinct, in what could be interpreted as a necessary phase of preparation, having left Chicomoztoc, arrived in Colhuacatepetl, and not as yet settled down. The scene describes a foundational rite of perforating/piercing the septum of the six Tepilhuan Chichimeca leaders with a vulture's bone and a jaguar's bone by Quetzalteuyac and Icxicouatl, thus nominating them as future tlatohque (district rulers) of the newly settled territory. The openings on the upper and bottom parts of the enclosure clearly imply as well as symbolize that such enclosures, like borders, were meant to be permeable, porous, and contingent. As evinced by this scene, such an enclosure functioned as a spatial framework for the performance of the foundational rites, at the end of which the actors were free to proceed to the more mundane activity of a final settlement.

Figure 1. Folio 21r in the Historia Tolteca-Chichimeca. Copyright Fondo de Cultura Económica, México.

The abovementioned enclosure is clearly related to foundational rites. In a landmark study on the subject, Elizabeth Hill Boone has taught us the basic components, acts, and features included in the graphic accounts of such rites. In her study, she has also claimed that “No single Nahua manuscript describes foundation rituals in any detail” (Boone Reference Boone and Vega2001:547–573). We have a number of primary sources, both graphic and alphabetic, copied and transcribed during the second half of the sixteenth century from pre-contact originals that vividly portray the various, but distinct acts involved in foundational rites. Among these sources are the Corpus Xolotl, the Codex Chimalpahin, the Códice Chimalpopoca Anales de Cuauhtitlan y leyenda de los soles, and Alva Ixtlilxochitl's Historia Tolteca-Chichimeca. The Códice Chimalpopoca Anales de Cuauhtitlan y leyenda de los soles provides an account of foundational rites held in the tenth century a.d., in the form of a journey to the four cardinal points of the assigned territory, followed by the shooting of arrows in these four directions, and another at the heart of the valley, where the divine lands [teotlalli] were located. The shooting of the arrows was defined as part of an act of homage, an offering to the gods in charge of the four cardinal points. The four colors and the four corresponding signs of a vulture (cuauhtli), a tiger (ocelotl), a snake (coatli), and a rabbit (tochtli) are time and again juxtaposed in an inseparable manner. Afterwards, the codex describes the Chichimec's ritualized actions and the marking of the boundaries among the various towns in the province of Cuauhtitlan (Velázquez Reference Velázquez1975–1977).

What I interpret as a “mock battle” component is dated for the thirteenth century by the early seventeenth-century Chalca chronicler, Chimalpahin Quauhtlehuanitzin. He recounts how, during the year Eleven House (1269), two rulers departed from the altepetl of Tenanco and climbed the summit of Mount Chalchiuhmomotztli Amaqueme, “and then at the summit contended against two other personalities, the ruler of Amaquemeque and his elder brother, Tlilecatzin Chichimec yaotequihua.” Either possessing true Chichimec roots or resembling their Chichimec ancestors,

they fought one another; they forthwith divided (the land) among themselves. They each took half of Mount Chalchiuhmomotztli Amaqueme. Then, [Atonaltzin and Tliltecatzin] established the altepetl of Totolimpan Amaquemecan in the aforesaid year, and they set up and established their boundaries [ynquaxoch]. Each of the aforesaid rulers [Atonaltzin and Quahuitzatzin] who had shot arrows at each other, now ruled his own property (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Schroeder and Ruwet1997:vol. 2, pp. 60–64).

From Anderson et al.'s interpretation, this event is described as an initial battle, which ends in an agreement about land division—and not a mock battle.

Good evidence for the sustenance of such procedures and their original nature as foundational rites is found in the primordial title of San Martín Ocoyoacac, a town located in the valley of Toluca. (The title was first published by Margarita Menegus in its Spanish translation: “Los títulos primordiales de los pueblos de indios.”) Studying such titles in depth, Lockhart assessed the sacredness of the foundation rituals described in these texts. He recognized the vital aspects of these rituals, extending beyond these texts (Lockhart Reference Lockhart, Collier, Rosaldo and Wirth1982). Let us first consider what is recounted in the alphabetic text:

And now the old men have gone … five darts they carried and they went to locate themselves facing the mountain; there they fired toward Chimalapan, and the darts came to a stop … ten potent darts, fearful wooden arms and shields, so that they should unite by the water or on the water banks … there the boundary line passes, there we grant our sons and grandchildren their limits, with shields [chimalli], with wooden armament and with darts … (Título Primordial de San Martín Ocoyoacac, Archivo General de la Nación, Mexico, Tierras, vol. 2998, Exp. 3, 3ª, f. 28r–32v; my translation).

Enclosures in the Corpus Xolotl

The Corpus Xolotl majestically stands at the threshold between the preconquest and the postconquest Aztec worlds. As such, it aims at faithfully conveying the core part of the preconquest Aztec modes of narrating histories and communicating its unique graphic representations. At the same time, however, it contains some significant Spanish-Catholic features and adjustments that have to be taken into consideration when deciphering its diverse contents. The preserved documents, ten leaves plus three fragments, are located within the “Mexican Manuscripts” collection at the Bibliothèque nationale de France. The codex is generally estimated to have been compiled somewhere between 1540 and 1546 (Douglas Reference Douglas2010:25–26). I tend to agree with Douglas that this codex was created no earlier than the third decade of the sixteenth century. Moreover, I base my own estimate on the assumption that work on the compilation of this codex was carried out under the close inspection of the Franciscan friars who resided in Texcoco at the time, which consequently impacted the codex's style. This is evident in the unique visual portrayal of the Christian mode of how the dead bodies of most of the indigenous rulers are lying down in the codex, apart from two, the Texcocan ruler Ixtlilxochitl and the Azcapotzalcan ruler Tezozomoc, who are visualized as being given Aztec traditional burials of cremation. The quimilli (bundle of the dead corpse) is always represented in Aztec pictography with ropes-knots, while in this codex, the dead corpse is actually covered by a (Christian) folded shroud (cf. Offner Reference Offner2011). Moreover, throughout the leaves, the overwhelming majority of the corpses are facing south, the region where death occurs, but also where regeneration occurs, according to Nahua cosmology. The south is also the region of re-generation, so that it could be easily merged with the Christian dogma of reincarnation.

The Corpus Xolotl has been studied by such leading scholars as Calnek (Reference Calnek1973), Dibble (Reference Dibble1980 [1951], Reference Dibble and Michelet1989), Lesbre (Reference Lesbre1999, Reference Lesbre, Navarrete and Olivier2000), Offner (Reference Offner1979, Reference Offner2011, Reference Offner, Brokaw and Lee2016, Reference Offner2017, Reference Offner, Brylak, Rosado and Barrio2018), Thouvenot (Reference Thouvenot1988, Reference Thouvenot1990a, Reference Thouvenot1990b, Reference Thouvenot1992), Douglas (Reference Douglas2010), and Johnson (Reference Johnson2018). Nonetheless, the deciphering of its complex contents still requires further effort and merits a more nuanced comprehension of both its overt and covert facets. I hereby attempt to connect the dots between major phenomena that surface from within the Corpus Xolotl and compatible sources ranging from central Mexico to greater Mesoamerica.

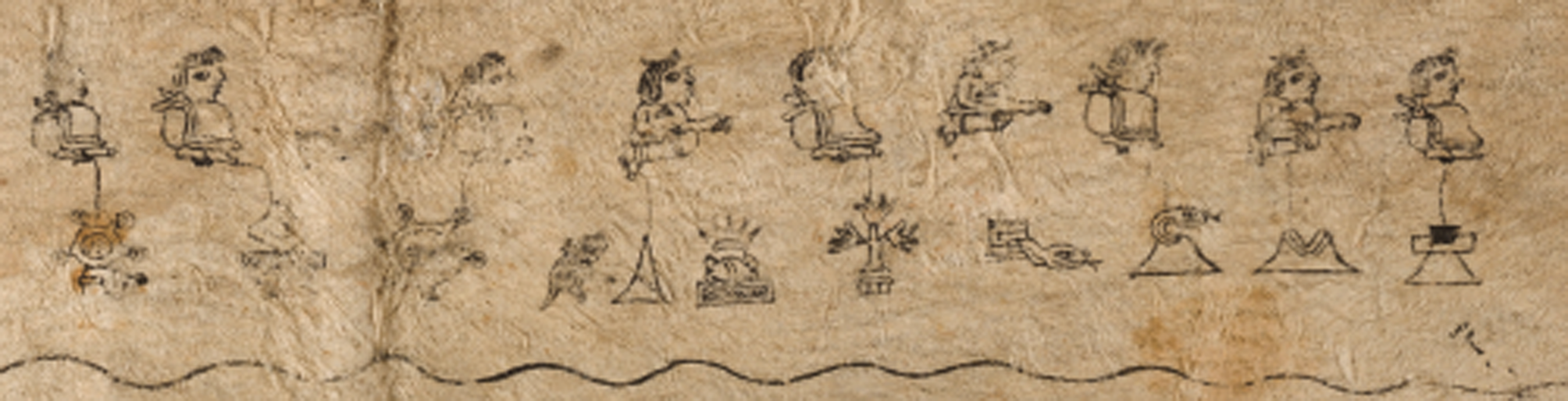

The Corpus Xolotl's historical narration begins around a.d. 1230 (Santamarina Novillo Reference Santamarina Novillo2006), recording Chichimec conquests, settlement, founding events, and timespans of rulership and warfare among emerging ethnic states in central Mexico between the middle of the fourteenth century a.d. and 1431. The first leaf (X.010) of the Corpus Xolotl, in the center of the page, portrays the Chichimecs’ first entry into the Valley of Mexico, in the year of Ce Tecpatl. Still in their nomadic stage, the Chichimec groups, headed by Xolotl and his son Nopaltzin, together with three allied leaders, are envisaged entering the Valleys of Mexico and Toluca, forming the first local alliances, taking possession of the land, and then establishing permanent settlements and towns in and around Tenayucan. Xolotl and Nopaltzin, father and son, some accompanying Chichimec dignitaries as well as macehuales (commoners), are visualized approaching each of the territories to be settled and climbing the highest mountains in the vicinity. There, one senior Chichimec lord accompanying Xolotl is seen “taking possession” of these lands in a symbolic-ritualistic manner (Corpus Xolotl, Bibliothèque nationale de France, Fonds Mexicain No. 1–10, leaf 1).

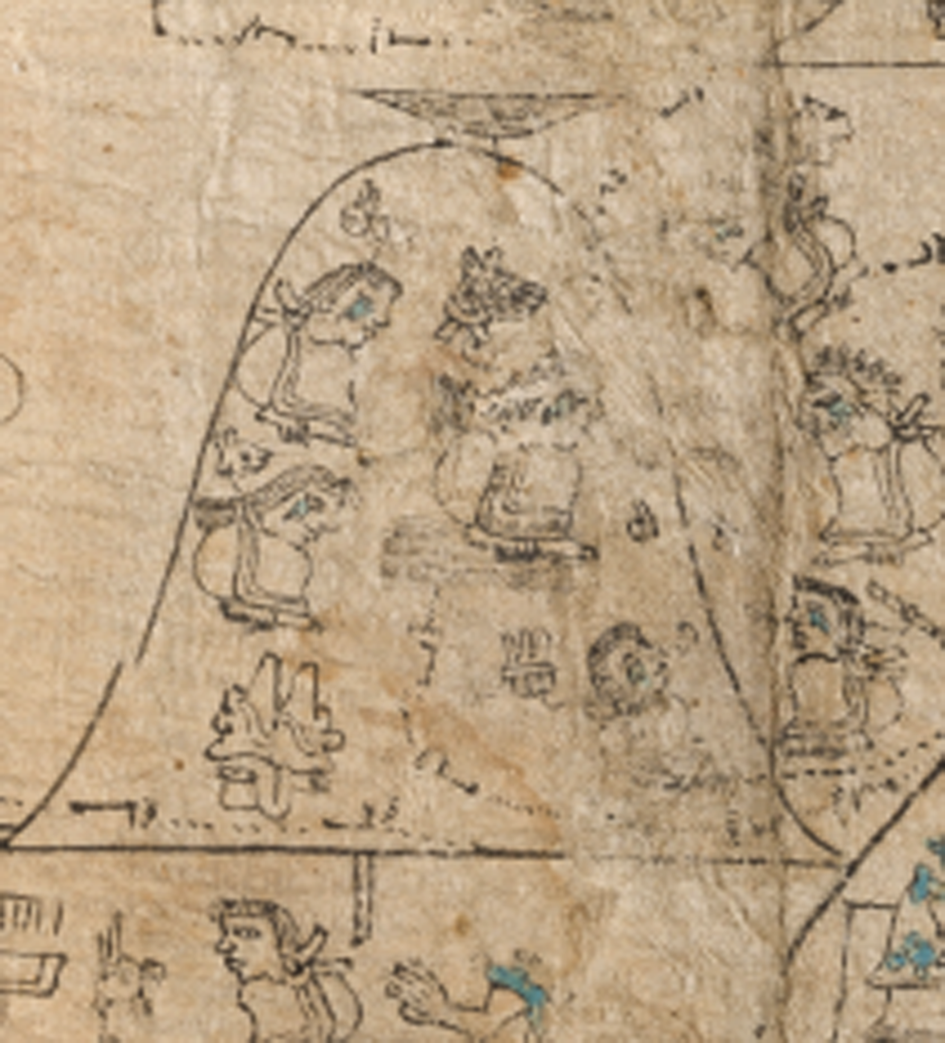

Next, on leaf X.020 of the Corpus Xolotl, the central scene depicts Xolotl and Nopaltzin, father and son, facing each other, while demarcating with darts what I propose to interpret as an enclosure, for the purpose of hunting deer; the given enclosure is located east of the city of Texcoco (Figure 2).

Figure 2. The “Enclosure,” Codex Xolotl, leaf X.020. Reproduced with permission of the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Fonds Mexicain No. 1–10.

The enclosure appears to be set on top of a green-painted, nameless mound. The same mound reappears on the next leaf (X.030), in the very same location, east of Texcoco, but now without the enclosure, but already named as Xolotl, or Xolotepetl (Figure 3). I believe that this mound represents the initial site of Tetzcotzinco's future palace-garden abode, built on a rising hill at the time of the Texcocan ruler Nezahuacoyotl (Figure 4). The remains thereof are still visible today (Figure 5). P.E.B. Coy believes that what is normally considered to be the toponym of Texcoco actually refers to the mound by the name of Texcotzinco. He bases his claim on the conical shape of this mound, as it appears from the west (Coy Reference Coy1966).

Figure 3. Xolotepetl, Codex Xolotl, leaf X.030. Reproduced with permission of the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Fonds Mexicain No. 1–10.

Figure 4. Mount Tetzcotzinco during Nezahualcoyotl's time, Codex Xolotl, leaf X.090. Reproduced with permission of the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Fonds Mexicain No. 1–10.

Figure 5. The archaeological site of Tezcotzingo, on top of the mound. Photograph from Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Texcotzingo.

Below the mound in Figure 1, there appears the date of the creation of the enclosure, 1 tecpatl—that is, fifty-two years after the beginning of the count on the date of 1 tecpatl of leaf X.010. Attached to the enclosure is a black carbon line, connecting it to the northern altepetl of Tolcuauhyocan, Tollantzinco, Cempohuallan, and Tepeapolco (Figure 6). I interpret this thick black line (tlilantli) connection as signifying a political act of bequest and allegiance by Xolotl to his son, Nopaltzin (as well as to subsequent generations of heirs), of those five Hñähñu altepetl which will form part of the future Texcoco-Tetzcotzinco's patrimony, in the form of tetzcocatlatocatlalli (Texcocan señoral property), or, eventually, tequitcatlalli (tribute or patrimonial lands), as depicted on the following leaf (X.030). It was also in one of these major altepetl, namely Teotihuacan, during the 1530s, where Hernando Cortés Ixtlilxochitl, one of Nezahualpilli's heirs, claimed patrimonial rights over the same lands originally bequeathed to his ancestors by Xolotl (“Tanto del testamento de D.n Fran.co Verdugo Quetzalmamalictzin,” Bibliothèque nationale de France: Fonds Mexicain, 243, April 8, 1563).

Figure 6. Texcoco's patrimony of the Otomi altepetl. Reproduced with permission of the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Fonds Mexicain No. 1–10.

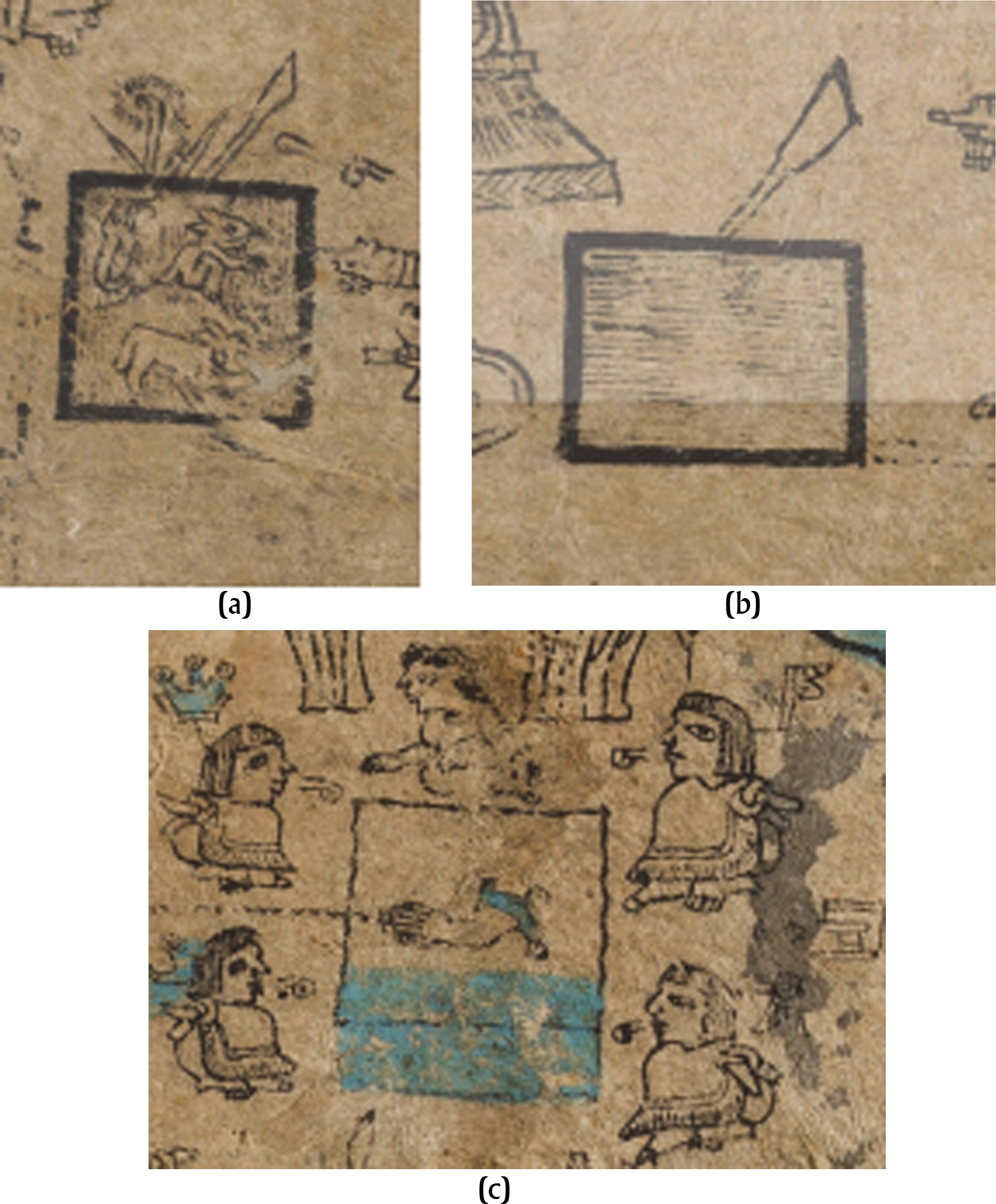

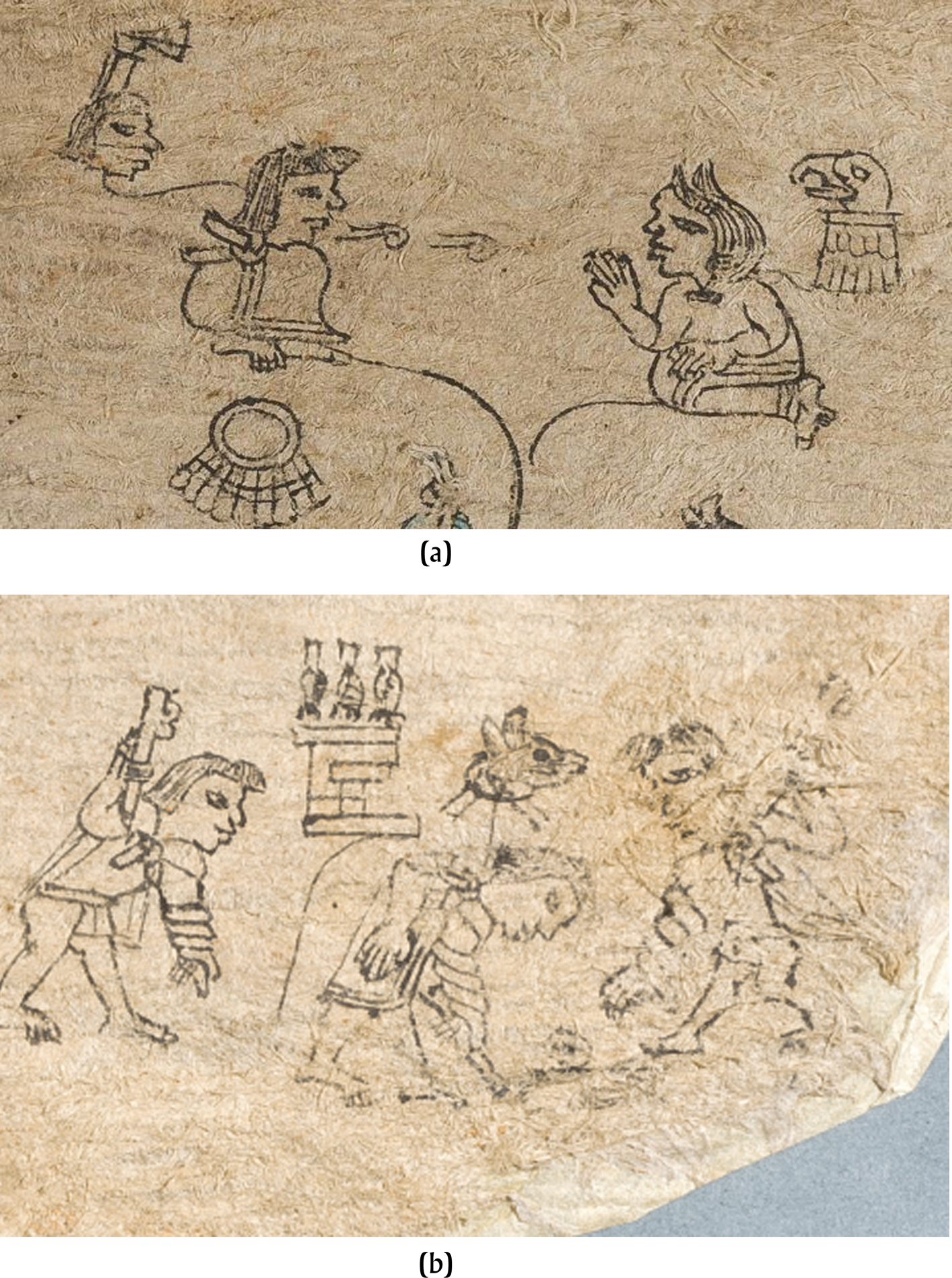

On leaf X.020, the enclosure itself functions as the site of enactment of the bequest. The northern area was where the ancient ethnic state of Texcoco would flourish in generations to come. Therefore, much space and contents in the Corpus Xolotl are naturally dedicated to that area. It was also in this territory that the six non-Nahua leaders arriving in the valley were assigned by Xolotl to settle and become tlatohque (sovereign rulers; Castañeda de la Paz Reference Castañeda de la Paz2013; Offner Reference Offner1979). On leaf X.020, they are already visualized as settled in the northern towns, with their established tlacamecayotl (genealogy), and being levied tributes of tochtli (rabbits; Figure 7a).

Figure 7. (a) A fenced enclosure of hunting grounds; (b) a fenced milli enclosure, as tribute payments to the lords of Texcoco; (c) a fenced chinampa enclosure to be cultivated by the settling-in Mexica groups (Codex Xolotl, leaves X.030, X.040). Reproduced with permission of the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Fonds Mexicain No. 1–10.

The Spanish verb cercar signifies to erect a fence of unspecified materials (tepantli, tlatzontli) around a forest to create hunting grounds to provide tequitl (tax) of prey and agricultural commodities to the overlords. The Texcocan nobility possessed fenced-in hunting grounds for procuring animals for the consumption of meat, while the commoners had to hunt in open areas, presumably with less game (Figure 7).

Let us now proceed to the interpretation of this unique scene. One is tempted, at first, to address the glyphic conjunction appearing here as a toponym, made up of matzatl (deer) + atl (water) + pantli (flag) = Matzaapan. But Dibble (Reference Dibble1980 [1951]:37) describes this scene in the following manner: “Evidently enough, Xolotl set up with his son an enclosure for hunting in the mountains behind Texcoco.” Though Dibble generally chooses to rely closely on the Texcocan historian Fernando de Alva Ixtlilxochitl's interpretations of the scenes in the Corpus Xolotl, he does not do so in this case. However, as Alva Ixtlilxochitl emphasizes, the given enclosure before us is visibly very different in all of its aspects to the enclosures visualized on leaves X.030 and X.040 (Figure 7).

In his Historia de la nación chichimeca, Alva Ixtlilxochitl describes the scene as follows: “During this same year [of ce tecpatl], he [Xolotl] enclosed a large forest area in the Sierra de Tetzcoco, to where he assigned a quantity of deer, rabbits, and hares, and in the middle of which he set up a temple, in which Prince Nopaltzin or his [Xolotl's] grandson, Pochotl, would offer their first morning hunt as sacrifice to the Sun” (Alva Ixtlilxochitl Reference Alva Ixtlilxochitl and O'Gorman1975–1977:vol. 2, p. 46).

If we compare Alva Ixtlilxochitl's account with Dibble's, we immediately notice that the scene's sacrificial-ritualistic context, as well as the temple/shrine in the middle of the site, are completely absent from the latter. Dibble was obviously matching Alva Ixtlixochitl's account with what is actually visualized in the Corpus Xolotl, and elements or objects that “were not there,” were this time discredited and therefore eliminated from his own reading of this scene. Nevertheless, the most plausible explanation for Alva Ixtlilxochitl's distinct reading of the scene is that he was keen to adhere to Acolhua-Texcocan social memory versions, with which he was acquainted and which may have helped him interpret this significant scene much more closely to its original context.

In contrast to Dibble, revisiting the scene in Figure 2 merits a cautious, though scrupulous re-inspection. On the outer layer, what is apparently projected to us within this enclosure is a plot of land, distinguished by its sandy-yellow shade and wave-like brushstrokes. On the covert layer of the scene, however, we have what I argue to be, in fact, a ritual precinct, the components of which are as follows: deer, water, observation, banner, altar/pyramid. Therefore, the conjuncture of glyphs that we observe should be properly read as: mazatl + atl + tlachia + pantli/tethuitl + tzacualli/momoztli. Furthermore, considering the essential elements in Alva Ixtlilxochitl's account that are missing from the scene before us, I propose that the lower part of the enclosure may well be the very location of the mentioned altar, where sacrificial offerings were made to the gods, and which is represented here by the pantli/tetehuitl (flag/banner) glyph above the tlachialoni glyph (Figure 8).

Figure 8. The tlachia+pantli glyphs, in the middle of the enclosure. Reproduced with permission of the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Fonds Mexicain No. 1–10.

In fact, this glyphic conjuncture of tlachia+pantli glyphs is the only place in the entire Corpus Xolotl where this conjuncture appears, and where a preconquest version of a “flag,” or banner (tetehuitl) appears. All other flag representations show Europeanized ones. What we have here, by sheer contrast to other “flags” throughout the Corpus Xolotl, is actually a tetehuitl, defined by Dehouve (Reference Mikulska, Barrio and Rosado2009:22) as papel sacrificial. Mikulska (Reference Mikulska, Barrio and Rosado2016) has elaborated on the meanings of banderas de sacrificio, sacrificial paper or ritual banner, utilized to cover offerings or to guide the participants into the sacrificial precinct. Accordingly, there was an additional expression in use: amapantli (amatl+pantli), flags, banners made of paper, which were the only ones exclusively used in rites of death or in acts of sacrifice (Mikulska Reference Mikulska, Barrio and Rosado2016:105). In book 2 of the Florentine Codex we have the following description of the use of tetehuitl within the cycle of rites during the month of Quecholli:

At dawn, they wore again their paper covering, and guided by the banner carrier, they proceeded to the place of sacrifice. Four priests climbed toward the four captives who were tied by their arms and legs on the top of the pyramid, where they were to be slain on the sacrificial stone. It was thus said: “thus like they are killed like deer; they serve like deer who, likewise, meet their death” (Sahagún Reference Sahagún1979:vol. I, bk. 2, f. 77v–82v).

The last feature, the captive's deer metaphor, fits in perfectly with the image of the deer in this scene. In the upper part of the enclosure is a small green elevation, which may clandestinely represent a tzacualli (temple-pyramid) or a momoztli (a round, stone mound that served as an altar). There is no doubt whatsoever that this particular enclosure could have been used for a variety of sacred purposes by dynastic rulers, or by the local priesthood, particularly as the iconographic elements do point to a variety of directions.

The Social Facet of “Enclosures with Inclusion”

Up to this point I have focused on the ritualistic facet of such “enclosures with inclusion,” some of which are inseparable from what are named as foundational rites. I claim that the ritualistic phase within such “enclosures with inclusion” is an essential phase preceding a final settlement, and the creation and development of social ties and social ramifications. Let us now observe the social context of this metaphor of “enclosures with inclusion.” The Texcocan chronicler, Alva Ixtlilxochitl, tells us about sacred knots of “feather-grass” that were used by the Chichimec leaders during the settlement activities in the Valley of Mexico to create enclosures and delineate land assigned to the different vassal groups to settle on (Reference Alva Ixtlilxochitl1891–1892:295–304)—that is, the very same action of creating enclosures for the sake of establishing norms of tribute collection for the overlords was also utilized to let diverse settling groups into common grounds, as visualized in Figure 7c.

Let us observe, for example, the following excerpt from the last paragraph of the Historia Tolteca-Chichimeca, which deals with the setting of the limits already under Spanish rule. The Historia Tolteca-Chichimeca, an early colonial, partly graphic and partly alphabetic manuscript, was composed in the town of Cuautinchan between 1545 and 1563, and commissioned by don Antonio de Castañeda of the Cotzatzin noble house, for the sake of deliberating the borders among several former altepetl in the eastern areas of Tlaxcala-Puebla. In the last section dealing with the setting of borders under the Spanish, it is said: “II calli xiuitl. Inic uitza juez ytoca sanctouval quiualiua presitente mexico ypampa tepantli yn itechcopa totomiuaque ynic motepaniaya” (“During the year 2 calli. Then came the judge by the name of Sandoval, sent by the president of Mexico [Audiencia of], for the sake of the limits with the Totomiuaque, who raised their enclosures”; Kirchhoff et al. Reference Kirchhoff, Güemes and García1976:f. 51r). We should pay close attention to the unique verb used here in Nahuatl, motepaniaya, which the three authors translate as cercas (in Spanish). As this is a verb, they translate it as “to raise enclosures,” from tepan-tli, “enclosures.” The authors explain that during that year (1532), the Totomiuaque were planning to extend their limits and to include Cuauhtinchan and Tecalco (Kirchhoff et al. Reference Kirchhoff, Güemes and García1976:f. 51r, n8). “Due to this, Fray Cristobal de Zamora reunited the tlatohque of Cuauhtinchan, Tecalco, Tepeyacac, Tecamachalco, Quecholac and from Totomiuacan to reach a settlement” (Kirchhoff et al. Reference Kirchhoff, Güemes and García1976:232).

Now I would like to introduce to this scheme the reading of such metaphors from the perspective of the principle of what I call “unity within diversity.” Examining the semantics of the powerful representation of unity within diversity in Mesoamerican cosmology in general, and in abundant Teotihuacan murals in particular, we find that the motif of entwined serpents may well have been an important symbol of transcendence across time, combined with a supernatural state reached through a shamanistic journey into otherworldly abodes. (One is able to see this kind of a metaphor represented within the frameworks of ritual enclosures, in the Codex Borgia, pp. 29–32.) In Nahua iconography, otherworldly forces (nahualli) are often represented by the figures of snakes. Such a snake is also the armament of the god-sorcerer Huitzilopochtli. In Karttunen's analytical dictionary of Nahuatl, however, we find that such representation goes beyond its symbolic context, deep into social contexts. Karttunen defines the noun coameh, literally meaning twin/snake, as follows: “This has two distinct senses, the concrete ‘snake’ and an abstract one, involving reciprocity … This latter use is involved in the use of ‘coatl’ (snake) to mean ‘twin’ in the expression of a host-and-guest relationship,” and proposes to interpret the verb coalotz as “to invite someone” (Karttunen Reference Karttunen1992:36).

In central Mexico, altepetl were founded on diverse groups settling on shared land, each retaining its autochthonous identity. Directly related, we are able to find the Nahuatl expressions tetlan or tetzalan, meaning “among others,” “living among [other] people,” or “passing through others” (Karttunen Reference Karttunen1992:235; Molina Reference Molina2001b:108). In his Nahuatl–Spanish dictionary, Fray Alonso de Molina, a sixteenth-century Dominican philologist, provides an example in the entry related to tetlan: tetzalan tenepantla ninoquetza meaning, “make peace among those who quarrel or fight,” or to the contrary, in its derogatory form: tetzalan tenepantla motecani malsin que mete mal entre otros (slanderer, who lives waywardly among others) (Molina Reference Molina2001b:111). I therefore propose that in Aztec/Nahua thought, enclosures could well have been conceived as spaces of inclusion and incorporation of “others,” other groups, and incoming peoples, or different social strata, hence functioning as enclosures with inclusion. Moreover, I argue that the etymological interpretation can also be adopted within the context of inter-ethnic and inter-group social relations, symbolizing social reciprocation among distinct ethnic groups and social strata, sharing a common space.

For connecting the concept of enclosures with inclusion to its socio-ritualistic manifestations, we have indigenous accounts concerning boundaries that were put into alphabetic writings between the early seventeenth and the late eighteenth centuries. They are called títulos primordiales or primordial titles. James Lockhart was the first to break new ground in these indigenous sources, in the wake of Charles Gibson, who had claimed that acts of foundation of a particular town or community on its territory were a key historical component in these documents and thus acknowledged a vibrant oral tradition in these manuscripts. Lockhart's most significant reference is to the sacredness of the foundation rituals described in these texts and his recognition of their vital role, beyond the texts per se: “More than the construction of the church dedicated to the patron saint, still more than the troubled episode of the congregations, the marking of the borders was the keystone of the foundation of the pueblo; it was even the principal subject of the titles. This was the most notable act of the foundation, a spiritual act, almost sacramental” (Lockhart Reference Lockhart, Collier, Rosaldo and Wirth1982:367–393). Later, other scholars, such as Serge Gruzinski, Stephanie Wood, Robert Haskett, Hans Roskamp, Michel Oudijk, Lisa Sousa, and Kevin Terraciano, followed the path opened by Lockhart and contributed extensively to our understanding of the contents and contexts of the primordial titles pertaining to Matlatzinca, Tlalhuica, P′urhépecha/Tarascan, Zapotec, Mixtec, and Maya groups (Gruzinski Reference Gruzinski1993; Haskett Reference Haskett2005; Lockhart Reference Lockhart, Collier, Rosaldo and Wirth1982; Megged Reference Megged2010; Menegus Bornemann Reference Menegus Bornemann and Bornemann1998; Oudijk Reference Oudijk2002; Oudijk and Romero Frizzi Reference Oudijk and Frizzi2003; Pérez Zevallos and Reyes García Reference Pérez Zevallos and García2003; Romero Frizzi Reference Romero Frizzi, Ángeles, Megged and Wood2012; Romero Frizzi and Vásquez Vásquez Reference Romero Frizzi, Vásquez and Frizzi2003, Reference Romero Frizzi and Vásquez2013; Roskamp Reference Roskamp2004; Sousa and Terraciano Reference Sousa and Terraciano2003; Wood Reference Wood, Noguez and Wood1998a, Reference Wood, Boone and Cummins1998b).

The Spanish colonial court of the Audiencia in Mexico City often supported the efforts made by indigenous communities of the Central Plateau to produce evidence for their primordial origins in an alphabetic form that was ascribed to past traditions, both oral and pictorial, and thereby to gain ownership over land and jurisdictions. This was especially relevant in dire straits, during the period of unrest in the wake of the Spanish colonial regime's Composiciones de tierras (land reforms concerning the reallocation of land for Spaniards as well as for indigenous communities) between 1636 and 1648. In some of the cases brought to the Audiencia in Mexico City, the primordial titles were the result of specific court orders for a new land survey and for cadastral “maps.” The legal processes involved in each of the indigenous communities’ renewed claims to land, in different phases, usually required the presentation of revised and revindicated versions of the history of the litigating community, that were sometimes accompanied by “maps” and illustrations portraying the community's historic leaders, their past jurisdiction, and their patron saints; a few of them also included a pictorial depiction of their acts of foundation. The communities were further required to mark on those maps the demarcations between one former altepetl and its neighbors, as they evolved over the centuries. In cases presented in court and initiated by court procedures, there was obviously more room for local political and ethnic maneuvering. But likewise there was far more room for the marked and reinforced presence of the bygone traditions of representing memory and history. In this light, the primordial titles were not mere anachronisms, but rather a joint effort by the local nobility and elites to preserve both dignity and prestige in view of the drastic transformations that their communities had undergone. Some of the legal processes, presenting claims and fighting contradictory claims by feuding native towns, tended to be lengthy, at times dragging on for nearly two centuries.

By the mid-colonial period, these documents echo, via social memory, preconquest socially oriented ritual practices of enacting metaphoric enclosures with inclusions, which were circulating in central valleys of Mexico and beyond. One of the richest in this genre, the primordial title of San Matias Cuixinco (transcribed in 1702), for example, formed part of a body of manuscripts known as the Anales de San Gregorio Apeapulco from this town, located near Ajusco and southwest of Lake Xochimilco (McAffe and Barlow Reference McAffe and Barlow1952). Although neither the date of their composition nor their presumed author is known to us, it is quite plausible that these accounts originate from Late Postclassic and Early Colonial semasiographic/graphic manuscripts and cadastral histories, painted somewhere around the 1520s or 1530s. In this particular document, the very act of setting up enclosures by tying knots of grass bundles appears on five occasions throughout the various texts. In the first, it reads as follows:

And it is for the sake of knowing, of acknowledging [that] they have gone binding together the tips of the grass roots one end to another, and in this manner they became knowledgeable of the limits … and this is the reason why in their language it is called tlatzotzonil, the limits of which were thereafter followed by binding together the grass one end to another upon the tepetlatles mounds and in the plains … (Archivo General de la Nación, Mexico, Tierras, Vol. 2819, Exp. 9, f. 40r–87v).

The Nahuatl verb tlatzotzontia is translated into Spanish by Molina as cercar, “fencing” in English (Molina Reference Molina2001b); thus the act of binding the grass simulates symbolically the act of putting up “enclosures with inclusion.”

In another such document, the primordial title of San Antonio Zoyatzinco (located near Amecameca, State of Mexico), it is said: “In the [year of] 1532 it was for the first time that throughout the plains the limits were bound together … which they name tlatzotzonil. All the limits that were situated in the plains were tied together” (Archivo General de la Nación, Mexico, Tierras, Vol. 1665, Exp. 5, f. 188r–194v). In the primordial title of Santiago Sula (located to the west of Zoyatzingo), we are told that while performing the act of tying/binding the grass together, the local ancestors encountered the Mexica who passed by, “appearing in the form of beautiful flowers [meaning, traveling souls of the departed, nahualli] and thereafter your fathers became [were turned into] quails, and began crying like quails, and the Mexica, terrified by the sound, abandoned the place” (Archivo General de la Nación, Mexico, Tierras, Vol. 1665, Exp. 5, f. 188r; also Gruzinski Reference Gruzinski1993:119).

Finally, in the primordial title of San Bartolomé Capulhuac (located east of Toluca, State of Mexico), we get the manifestation of “enclosures with inclusion” that delineate distinct groups. The document begins by recounting the origins of the town. Accordingly, the first group of migrant-settlers, who arrived in Capulhuac, consisted of ten Matlatzinca lineages, headed by both men and women leaders; only one of them spoke Nahuatl (he was certainly an interpreter, nahuatlato). The second group was of Otomíes (Hañúu). It comprised six lineages, also headed by both men and women. Thereafter, Tozocatzin, the local leader of San Bartolomé Capulhuac, is envisaged addressing the leaders of Xochitepec, warning them against trespassing the limits: “you can see that they are signaled with this sign of the entwined grass [malinalli], one end to another … go along and concentrate on guarding your community well” (Archivo General de la Nación, Mexico, Tierras, Vol. 2860, Exp. 1, f. 59v–63v).

What Are “Porous Borders” in Mesoamerican Thought?

Archeological studies provide us with two opposing models of borders. One school of thought advocates “closed” frontiers, in which human-made barriers affect the landscape, cultivate hostile environments and lead to an “ethnicity of borders,” whereby frontiers become zones of competition and differentiation. Relations shift away from cultural homogeneity. The other approach emphasizes porous borders. Accordingly, incursions or penetrations are not harmful acts. On the contrary, from the vantage point of border communities, such borders create contact zones and foster all kinds of cross-cultural phenomena. Porous borders facilitate people's movements, allowing for social inclusion. Goods and services cross borderlines, as do cultural values and ideas (Green and Perlman Reference Green, Perlman, Green and Perlman1985:171; Parkinson and Duffy Reference Parkinson and Duffy2007; Stoner Reference Stoner2012; Ohnersorgen and Venter Reference Ohnersorgen, Venter and Nichols2012; Venter Reference Venter2008:18–19).

During preconquest times, three major types of activities were employed to mark limits, which are discernible: (1) using natural features (ravines, lakes, mountain ridges); (2) tying bundles of grass; and (3) fixing poles in the four directions of an assigned land. If we look at how Molina treated tepantli in his Diccionario, we get two distinct forms related to limits: one pertaining to limits between milli, or plots of land, that are to be divided among heirs, or among a number of neighboring landowners: miltepantli: mojon olinde de heredad. linde entre heredades linde entre heredades de muchos. The other is connected to political/jurisdictional limits of an altepetl/confederacy: altepetepantli: sitio por cerco del pueblo. terminos, o mojones dela ciudad (Molina Reference Molina2001b:f. 4r, col. 2).

In central Mexico, natural barriers were, evidently enough, the most prevalent embodiments of what we call frontiers/boundaries. Standard geographic features such as rivers, lakes, mountain summits, and passes formed natural boundaries. Human-made limits, if utilized at all, were merely for the sake of delineating plots of land, or, temporarily, in areas in an ongoing state of war. Molina translated the Nahuatl word quaxochtli as altepecuaxochtli: sitio por cerco del pueblo; terminos o mojones de pueblo o ciudad, meaning “limit or boundary of land,” exactly because this translation fits the Spanish colonial terminology (Molina Reference Molina2001b:f. 88r, col. 2). Lockhart, on his part, came closer to the original Nahua terminology by analyzing the etymology. He observed that “the first element seems to be quāitl [tree/stick/rod] but that could lead to either quā- or quah. The second element shows no semantic affinity to xōchitl, flower” (Lockhart Reference Lockhart2001:231). In his Spanish translation of the Anales de Cuauhtitlan, Primo Feliciano Velázquez constantly translated quaxochtli as mojon, which is best rendered in English as “cornerstone” (Velázquez Reference Velázquez1975–1977). Like Molina, Velázquez was thus utilizing the Spanish conceptualization of limits and frontiers, which led to an erroneous translation of the Nahuatl term.

Drawing on Lockhart's etymological analysis, I suggest an alternative explanation, namely that quaxochtli was effectively an action-type expression in Nahuatl, instructing to use tall poles for marking land. This interpretation seems to be corroborated by the fact that xochtli is a well-known variant form of xochitl (flower/flowers). In the Zongolica region, flowering trees such as tzompanxochitl/ekimixochitl or icsote are often planted specifically to mark boundary limits (Magnus Pharao Hansen, personal communication 2020), which makes sense since they are highly visible and useful. Therefore, it is plausible that in preconquest times, tall wooden poles replicating tall trees were inserted in the four cardinal points of an assigned land. For the early colonial period, as well as for the precontact era, I was unfortunately able to find evidence for this practice only in an oral source transcribed into alphabetic writing, and not in any graphic source. The transcribed oral source is a unique account from around 1505, recounting the practice of fixing wooden poles in the four corners of an assigned land in the aftermath of a military onslaught. It was put into writing in the Matlatzinca town of San Mateo Atenco (Valley of Toluca) during the last decades of the sixteenth century. As recounted, the land to be delineated was first measured by the “Triple Alliance” delegates from Tenochtitlan, Tlacopan, and Coyoacan, using measuring rods. Afterwards, the assigned land was divided at the four cardinal points of a quadrant plan between the Metepec and the Atenco territories, using the Río Lerma as a line of reference: “They were working day and night, using torches to illuminate the area; round, wooden quahuitl [poles; land-measurement], five meters tall [a trés brazas; braza = 1.67 m] were then erected on the sites. On top of each pole, the lords of each town then tied, large, white tlalpilli [bundles] of grass” (Archivo General de Indias, Seville, Escribanía de Cámara, 161ª 1576, f. 228v, 226v–227r).

With regard to areas in preconquest Mexico where hostilities were a paramount factor, we learn from Mexican archaeology that throughout the vast, presumably continuous territory ruled by the Aztec Empire between 1428 and 1519, political and military limits were set up only in buffer zones, in recently conquered war zones, and between the Nahua peoples and those on “foreign” lands, such as the Tarascans. There were merely a few places that we can characterize as “frontier sites,” where garrisons and fortifications stood, and where buffer zones were established during continuous states of hostilities. As Ross Hassig notes, “The absence of garrisons is also associated with the general lack of fortifications. Even Tenochtitlan lacked major fortifications” (Hassig Reference Hassig1995:260). The very few frontier sites that archaeologists have been able to unearth were, for example, in the Tuxtla mountain area of today's southern State of Veracruz (Stoner Reference Stoner2012), close to the Tarscan State to the west, the Yopi in southwestern Guerrero, and the Chontales area (Xocotitlan, Atahuiztlan, Oztuma, Totoltepec, Cuecalan, and Chilapan), where a chain of forts was constructed along the respective frontiers, and where a buffer zone was established (Marcus Reference Marcus1984:50; also Pollard and Smith Reference Pollard, Smith, Smith and Berdan2003). Based on these studies, we may say that at least in the major areas under the control of the Aztec Empire, as well as its southwestern regions, toward the Mixteca Alta, the first model of frontiers was clearly confined to areas where states of hostility were likely to be temporary.

In her essay on Mesoamerican territorial boundaries, Marcus (Reference Marcus1984:53) notes that:

from the tribute lists of the Aztec we can draw with some precision the limits of their tributary “empire”; with the ethnohistoric data, we recover information essential to drawing the linguistic and political frontiers; from the archaeological record, we can actually map the fortified sites along or near the limits of the Aztec and Tarascan states.

What Marcus highlights as frontier points of orientation for central Mexico were Aztec garrisons located on the limits of the Tarascan and Chontales “states” only. Furthermore, in the Lienzo de Jicayán from the Mixteca area, Marcus identifies border/frontier towns based on their names, which seems highly speculative to me. She concludes that “The history of changing boundaries, as derived from texts, could serve as a directive for future archaeological research … Still more time would be needed to investigate the boundaries for earlier times” (Marcus Reference Marcus1984:56).

In her study of boundaries in the Aztec period, Frances Berdan discusses primarily “imperial frontiers,” characterizing them by similar traits as those used by Marcus (Smith and Berdan Reference Smith, Berdan, Michael E. Smith and Frances F. Berdan2003). Yet, as Helen Pollard and Michael Smith show, even during lingering hostilities, such frontiers or borders were porous in their nature; there was still room for trade and exchange of goods and artifacts across these borders, at least on the eastern front of the Aztec Empire (Pollard and Smith Reference Pollard, Smith, Smith and Berdan2003). Moreover, Dana Leibsohn (Reference Leibsohn1993) demonstrates how during the founding of Cuauhtinchan, after the defeat of their neighboring feuding altepetl, these settlers finally surveyed their boundaries and marked them by footprints moving from one site to another.

Consequently, it is reasonable to argue that within the vast territory of central Mexico, limits or boundaries, if and when they existed, were established only where hostilities became a common phenomenon among rivalling polities; and even in these cases, they were temporary and would not constitute a convention. For further clarification, let us take a close look at such an area of ongoing hostilities, namely the northern part of the Acolhuacan territory, between the Otomi of Xaltocan and the Cuauhtitlan Chichimecs, during the time of the Texcocan-Acolhua ruler Quinatzin (1275–1356), portrayed in the Corpus Xolotl. The Anales de Cuauhtitlan tell us that the limits [quaxochtli] of the Xaltocanecs remained there for merely nine years, during the war of the Chichimecs Chautitlanecs (auh inin Quaxochtli chiucnauh xihuitl in oncan icaca [icanca], auh in ixquich ica oncan manca yaoyotl ini yaoyuh Chichimeca Quauhtitlancalque; Velázquez Reference Velázquez1975–1977:no. 110).

Demarcations between Altepetl, Confederacies, and Inner Divisions

Drawing on Tomaszewski and Smith's Personenverband (personal association) approach, it may be plausible that preconquest Nahua jurisdictions and polities did not necessarily consist of distinct demarcated territories, but, as in other parts of central Mexico, were characterized by an identifiable pattern of what these authors term “overlapping areas of villages and peoples” (Tomaszewski and Smith Reference Tomaszewski and Smith2011), which means that jurisdictions and actual limits among the different social structures remained fluid and porous. For example, the four autonomous altepetl that made up what one could consider to be a “Tlaxcallān confederacy” or Huey Altepetl Tlaxcallān (the greater ethnic state) were actually rather amorphous constellations. They were superimposed upon much older and far more cohesive local social frameworks, networks, and institutions. A permanent teccalli (noble house) was not necessarily created around a single tlaxilacalli (subdistrict within an ethnic state) or altepetl jurisdiction, but such teccalli could be found in different locations scattered around a larger area (Megged Reference Megged2021).

In his obra magna James Lockhart maintained that larger public entities, such as the altepetl, the calpolli (literally, “big house,” usually a subunit of an altepetl; https://nahuatl.uoregon.edu/content/calpolli), the local community, or subsections had land rights, while lordly houses and palatial establishments of various kinds held their own seemingly “private” rights to land. Nonetheless, Lockhart leaned toward a porous categorization of such divisions in light of the inherent lack of differentiation between “public” and “private” in Nahua thought. For example, callalli (jurisdiction over plots of land held by a lordly household) were “not necessarily noncontiguous” (Lockhart Reference Lockhart1992:160–161). Hicks (Reference Hicks2009:573) highlighted the fact that land belonging to the teccalli was either privately owned (by a pilcalli = a lordly house?) or commonly owned by both men and women. It is, however, far more likely to be the case that the land itself belonged to “corporate entities,” including calli lineages, and was not divided and sold as personal property, especially during postconquest times (Lockhart et al. Reference Lockhart, Berdan and Anderson1986:85–86). As a follow-up to Lockhart, let us take, for example, one particular lawsuit in Tlaxcala in 1550, in which Yahualahuachtli attempted to prove his private ownership of land at a site called Xonacayuca, arguing that it was passed on by patrimonial inheritance and was not part of the common land of the teccalli, which was clearly contrary to traditional conventions. (The teccalli was set in the area, which is today located in the state of Puebla, northeast of Tlaxcala.) Baltazar Memeloc, the other contester, argued that the land belonged to his ancestors (huehuetlalli = patrimony), as a common teccalli possession, and that the recorded memory of this possession went back to 1490. He claimed to be the grandson of Timaltzin, the presumed founder of the teccalli (Megged Reference Megged2021).

Pleito por tierras entre Inés Teohuaxochitl y su marido Julián de Contreras, ella nieta de Tecpatzin, muerto hace 40 años, contra Baltazar Memeloc, nieto de Timaltzin, fundador del señorio y cacicazgo de Matlahuacala. Baltazar Memeloc afirma que Tecpatzin era advenedizo y natural de Otunpan y que caso en esta provincia con una señora llamada Mollactzin, hija de Chiquatzin, de la casa de Matlahuacala. Contiene pintura en papel europeo (42 por 31 cm) con glifos y texto en náhuatl y en español. (“Testamento de Tzocotztehutli Michpiltzintli,” Archivo de la Fiscalía de San Mateo Huexoyucan, municipio Panotla, Tlaxcallān, Exp. 1, 2 [10 marzo 1550–1551], copia del siglo dieciocho).

Cross-Marriages and Power Enclaves that Annul Borders and Create Enclosures

Concerning the area around Lake Texcoco between a.d. 1300 and 1430, the background scenery for the Corpus Xolotl, there are many indications pointing toward the idea that it was very likely conceived to be an indivisible territorial unit, shared by all of the people living around the lake. They were called chinampatlaca (“floating island dwellers”). Ahuxotl (Salix bonplandiana; willow trees) were planted around the chinampa (floating gardens) in Xochimilco, Chalco, and Texcoco, as natural borders. Tollin (reeds), which were used in commerce and for other diverse purposes, were regarded as an integral part of the town's property (pialli) and served for the purpose of co-sharing the lake among its various owners.

Benían con ynfinito pescado blanco de Mizquic y Cuitlahuac, Culhuacan y Yztapalapan, Mexicaçingo y lagunas dentro, Aztahuacan, Acaquilpan, Chimalhuacan y otros pueblos que están a las orillas de la laguna, con todo género de patos, rranas, pescado, xuhuilli, yzcahuitle, tecuitlatl, axayaca, michpilli, michpiltetein, cocolin, axolotes, anenez, acoçillin, y la diuersidad y géneros de abes de bolantería era cosa de beer tantos, y biuo todo, garças y urracas (Alvarado Tezozómoc Reference Alvarado Tezozómoc and Leon1975:chap. 87, f. 127v).

This aspect of sharing common property, in spite of ongoing cross-ethnic hostilities and intrusions, is highlighted in the Corpus Xolotl. Within the longue durée process of the formation of the ethnic states in central Mexico between the tenth and thirteenth centuries, newcomers were allowed to keep their gods and maintain autochthonous traditions and practices. The same happened with newly conquered lands: “When these lands were given away, the conquered land owners were not displaced. They continued to live on the land, work on the land, and pass it on to their descendants. They shared the profits of the land with the new owners” (Avalos Reference Avalos1994:273). Such an ideological stance is clearly extended to the realm of social relationships and political alliances, irrespective of ethnic divisions and political rivalries. It was challenged, in particular, at a time when accommodation of incoming foreign tlaxilacalli within foreign jurisdictions became the norm, not the exception.

Moreover, in none of the ten leaves plus the three fragments contained in the Corpus Xolotl does one find any real divide between Acolhuacan and Tepanec jurisdictions. On the contrary, substantial enclaves merged at some time or other within each other's proclaimed territory, a reality that allowed for consolidations of alliances across ethnic divides. Furthermore, the Corpus Xolotl actually stressed that unwavering ethnic territorial jurisdictions were non-existent, that jurisdictions rather remain fragile and fluid, and that no territory was ever unaffected or closed to incoming ethnic groups and their local impacts. In times of wars, recurrent acts of hostilities, and feuds in the area, the traditional pattern of migrating tlaxilacalli and their accommodation within foreign altepetl was a widespread phenomenon. A new subdistrict or a noble house could be established by an incoming group of closely related kin, led by their noble, forming a settlement nucleus that included the temple (teopancalli) and the ruler's palace. Under such circumstances, the incoming tlaxilacalli would eventually be absorbed into an already established teccalli by way of intermarriage between noblemen of the incoming tlaxilacalli and the daughters of local tlatoque (rulers). (For illustration, see the case of the two migrating tlaxilacalli of Tlailatlocan and Chimalpan, discussed below.) Gerardo Gutiérrez says about this process:

We assume that if the process of transfer of calpultin [subdistricts], and even pilcaltin [noble houses] was constantly repeated whenever there was a political reorganization as a consequence of dynastic changes, then, the reshuffling of lands was accentuated more within the limits of the altepetl. In addition, in certain cases in which conquests or inter-dynastical marriages were involved, such reshuffling could have exceeded the proper limits of the political unit itself, towards other altepetl (Gutiérrez Reference Gutiérrez, Aneels and Mendoza2012:49–50).

This Nahua practice of “welcoming strangers” is vividly portrayed on leaf X.070 of the Corpus Xolotl, and in even greater detail on leaf X.050. Moreover, leaf X.070 provides a vivid illustration of such a protocol in times of warfare. In the wake of the battles between Tepanec and Acolhua armies, Texcoco is already in disarray by the year 1 Acatl (1415). The entire Acolhuacan area is severely impacted by the rising superpower, Azcapotzalco, including substantial Tepanec enclaves forming within the Acolhua region. Above Huexotla, we see a chain of tlaxilacalli from Texcoco, such as Chalca and Mexicapan, as well as ruling and noble teccalli, established by rulers from Huexotla and Cohuatlichan, and their women, who were fleeing from their ethnic states and moving eastward to seek refuge near the mountain ridge. Some of those tlaxilacalli never returned to their places of origin and remained in the hosting ethnic states in the east (Figure 9; Johnson Reference Johnson2018:85).

Figure 9. Fleeing tlaxilacalli from various altepetl seeking refuge in the area between Tlaxcallan and Huejotzingo, Codex Xolotl, leaf X.070. Reproduced with permission of the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Fonds Mexicain No. 1–10.

Citing the Chalca historian Chimalpahin regarding the town of Amecameca (in the Chalca area), Mary Hodge stresses that during the recurring wars between Chalco and Tenochtitlan or with Azcapotzalco, people/tlaxilacalli from Amecameca sought refuge in the towns to their south. “Some Chalca remained in these areas … and even conspired to rule there” (Hodge Reference Hodge1984:50). Rik Hoekstra develops this theme, stating that during military campaigns and resulting migrations, “groups voluntarily submitted to a neighboring powerful lord in exchange for the use of land or for protection” (Hoekstra Reference Hoekstra, Ouweneel and Miller1990:73). Here I argue that those incoming groups and lineages subsequently formed their own enclaves within the hosting altepetl, with their distinct identity and loyalties to their places of origin. The Chalca polity plays a decisive role in the Corpus Xolotl. It was from there that major tlaxilacalli migrated to Texcoco. The Nonohualcatl lineage that eventually found its way to the altepetl of Texcoco may have originally migrated from Nonohualca into Cuauhquechollan, and from there to Chalco. The Tlailatlocans and the Chimalpanecans also arrived from there. The name of Tlacaximaltzin's lineage appears in Chalco as part of the departing Tlailotlacan tlaxilacalli, as seen on leaf X.040. The Tlailatlocan tlaxilacalli is observed migrating toward Texcoco, reaching the city on 4 Acatl (1275). Likewise, since Ce Tochtli (1298), the Chimalpanec tlaxilacalli migrated from Chalco Atenco to Texcoco, led by Xilocuechtzin. Both tlaxilacalli establish themselves in their new permanent places of residence during the rule of Quinatzin (1275–1356) (Figure 10; see also Schroeder Reference Schroeder1991:42–43). The Chalca people are also depicted in the Mapa Tlotzin as teaching the Chichimecs how to cook the raw meat that they ate, as well as how to become artisans.

Figure 10. The arrival of the four tlaxilacalli and the formation of ethnic enclaves within the altepetl with diversified loyalties, Codex Xolotl, leaf X.050. Reproduced with permission of the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Fonds Mexicain No. 1–10.

As is evidenced in the Corpus Xolotl, some hundred years after their arrival in Texcoco from the Chalca area, the Chimalpanecas still maintained distinct identities within the Texcocan ethnic state based upon shared origins, which meant that their loyalty to the Texcocan state remained questionable. Nevertheless, the final leaf of Corpus Xolotl (leaf X.101) is dedicated to the graphic representation of the mitigation and the elimination of tensions and animosities between former rivals; it thus leads back to the principle of unity within diversity. This final section of the codex was crucial for its authors, affirming Chimalpanecan and Tlailotlacan loyalty, legitimizing their status, and neutralizing earlier machinations against Acolhua rule. Likewise, renewed association and alliance between the Chimalpanecas and Tlailotlacans, and Nezahualcoyotl's tlacamecayotl are secured through the marriage between Totzquentin, Nezahualcoyotzin's sister, and Nonohualcatl, with Nezahualcoyotzin's approval (Figure 11); and through renegotiation of these two entities’ position in the Texcocan power structure in order to attain prestigious offices (see also Dibble Reference Dibble1965; Johnson Reference Johnson2018; Offner Reference Offner, Brylak, Rosado and Barrio2018).

Figure 11. (a) The marriage between Nonohualcatl and Totzquentzin; (b) the consecration of a new tlacochcalco (military training school), Codex Xolotl, leaf X.101. Reproduced with permission of the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Fonds Mexicain No. 1–10.

The Corpus Xolotl teaches us that the rationale behind porous divisions and contingent borders is deeply embedded in the notion that lineages had to embrace and include members of other competing lineages or states. Furthermore, it teaches us that such cross-marriages of inclusion did function as a kind of “scouting force” that included an entire entourage, for the sake of establishing solid power bases within a competing state. The codex stressed the direct links and blood ties extending across the Acolhua territory and ethnicity, reaching deeply into Tepanec ruling families. Rulers of the newly established ethnic states and ethnic constituents, whether large or small, customarily intermarried to reaffirm alliances and exert long-lasting control over territories, their ethnic enclaves within rival territory, and natural resources. Moreover, political loyalties to one's ethnic loyalties became porous, and divided interests subsequently overcame ethnic loyalties.

As this codex reveals, Tepanec rulers from the ethnic state of Azcapotzalco, for example, customarily married daughters of the Cohuatlichan rulers—intermarriages across the porous divide between Tepanec and Acolhua ethnicities (Santamarina Novillo Reference Santamarina Novillo2006:298). Itztacxochitzin, one of Ixtlilxochitl's sisters, was married to Chalchiuhtlatonac in Azcapotzalco; and Tecpaxochitzin, Ixtlilxochitl's first wife, was Tezozomoc's daughter from his second wife. Another of Tezozomoc's daughters, Chalchiuhcihuatzin was married to Tlatocatlazacuilatzin, the ruler of Acolman. Their son, Cuacuatzin, became the ruler of Tepechpan. Tezozomoc's other daughters married the rulers of Cohuatichan, Xaltocan, and Tenochtitlan.

In paragraph 78 of the Anales de Tlatelolco (Berlin and Barlow Reference Berlin and Barlow1948), it is mentioned that a pro-Tepanec governor was installed in Tepechpan. As is seen on leaf X.100 of the Corpus Xolotl, the appointment of pro-Tepanec governors in Cohuatlichan, by Maxtla, Azcapotzalco's ruler, prior to the Tepanec War (1428), led in the aftermath of that war to the need for fluid negotiations between Nezahualcoyotzin's emissaries and those governors with regard to maintaining some control over local affairs. The Corpus Xolotl allows us to discern the existence of major pro-Tepanec enclaves within Acolhuacan territory, in which Tepanec rulers regularly set up military governors as well as permanent local rulers. Through intermarriages, Tepanec lingering presence in these Acolhua towns created nuclei of joint Tepanec–Acolhuac noble lineages (for comparison with Chalco, see Hodge Reference Hodge1984:51).

There was, for example, the pro-Tepanec Chimalpan tlaxilacalli in Texcoco; additional ones are located in Acolman, Tepechpan, Cohuatichan, Xaltocan, Huexotla-Atenco, and Texcoco-Chimalpan. Among those, Cohuatichan remained the undeclared capital of the Acolhuacan ethnic territory for centuries. Quetzalmaquitzin and Tochintecuhtli were the two pro-Tepanec rulers installed there, way before the outbreak of any warfare in the area. Huexotla Atenco (the westernmost part of Huexotla), another of the Tepanec enclaves in the Acolhuacan territory, was controlled by Tlacopan, a member of the pre-1428 Tepanec Triple Alliance (between Azcapotzalco, Tenochtitlan, and Tlacopan), through a governor (Tozatzin) he installed in that altepetl. Tepanec presence is further attested by the glyph or the anthroponym of Yaotzin in the Florentine Codex, which contains a tetl glyph that may allude to his Tepanec provenance, namely a Tepanecatl (a Tepanec person). Also, his tecpilotl (the headdress of early Texcocan or Tetzcocan rulers) is non-Acolhua. We are told by Sahagún (Reference Sahagún and Facsimile1997a [1556]:bk. 8) that it is only from the sixth ruler in Huexotla that we see these rulers seated on tecuhtlatoca icpalli (literally, a seat for lordly rulers; Molina Reference Molina2001b:f. 93v, col. 2), that is, only by the time they were required to levy tribute for the Tepanecs, which means that they were installed as governors directly by Tlacopanayotl (Tlacopan's control; Velázquez Reference Velázquez1975–1977:no. 142; Sahagún Reference Sahagún and Facsimile1997:bk. 8). Moreover, by that time, Huexotla had been subdued by Itzcoatl and Nezahualcoyotzin's armies, which, according to Torquemada (Reference Torquemada1975–1977:vol. 2, p. 200), suppressed a local pro-Maxtla rebellion incited by Maxtla and led by the local Acolhua leader Huitznahuatl (not the name of a person, but a high army rank).

In Acolman, Teyolcocoatzin, one of Tezozomoc's sons-in-law, married Tezozomoc's daughter, Chalchiuhcihuatzin, and thus became Tezozomo's close ally against Ixtlilxochitl and retained his tlatocayotl of this important altepetl (Figures 9 and 12; Calnek Reference Calnek1973:424).

Figure 12. Acolman's Tlacamecayotl and its merger with Tezozomoc of Azcapotzalco through intermarriage, Codex Xolotl, leaf X.050. Reproduced with permission of the Bibliothèque nationale de France, Fonds Mexicain No. 1–10.

Moving beyond Gillespie's (Reference Gillespie1989) initial argument about women from Toltec lineages, a discussion of the entangled marriage alliances of Mexica rulers, focusing particularly on don Pedro Moteuczoma's marriages, shows how, on the one hand, Mexica nobility plotted marriage alliances that pulled its participants towards negotiating territorial holdings, while on the other, this opened the door to disputes among heirs. This was the case for Doña Isabel and Don Pedro, who were able to fight each other precisely because there was ambiguity about limits or boundaries to the possessions they claimed. David Tavárez describes it as “genealogical politics,” and adds that “such an approach to marriage alliances and inheritance was an instrumental strategy that structured the dynastic history of Tenochtitlan, and it continued to be employed by the members of the Nahua royal lineages in the sixteenth century” (Tavárez Reference Tavárez, Boone, Burkhart and Tavárez2017:126). Tavárez cites the case of the marriage between Ilancueitl and Huehue Acamapichtli in this context. According to Alva Ixtlilxochitl, in his Historia de la nación chichimeca, and also to Alvarado Tezozomoc, in his Crónica Mexicayotl (1975), Ilancueitl was Acamapichtli's aunt, and the daughter of Achitometzin, the first ruler of Culhuacan. Acamapichtli himself was the son of Acolhua, the first ruler of the ruler of Azcapotzalco and of the Tepanecs. This marriage was ordered by Nopaltzin, precisely for the sake of consolidating an alliance between the Colhuas and the Tepanecs (Historia de la nación chichimeca, Alva Ixtlilxochitl Reference Alva Ixtlilxochitl and O'Gorman1975–1977:chap. 7). In the Crónica Mexicayotl (Tezozomoc Reference Tezozomoc1975:no. 116) it is said: “Señor de Coatlichan; les dijo a los mexicanos que la madre de Acamapichtli no era Ilancueitl que Ilancueitl era su tía pero que ésta lo había adoptado, por lo que se lo podían llevar, pero que llevaría consigo a su madrecita con la que ya en Tenochtitlan lo casaron”. In this regard, one should be able to find comparative cases supporting the argument that lineages had to embrace and include members of other competing lineages or states, from other areas of Mesoamerica. Tavárez, for example, examined a Zapotec título primordial, which in fact provides a good example of a community, Yelabichi, which was welcomed by and merged with Yetzelalag—the título provides an argument for this merging, and forms an alliance against another neighboring community (Tavárez Reference Tavárez2019).

CONCLUSION

By reinterpreting focal scenes in the Corpus Xolotl and linking them with compatible sources from across central Mexico and beyond, my study has aimed to introduce a novel approach to what were boundaries in the Aztec/Nahua worldview. I argue that temporary boundaries/limits were set only in areas of ongoing hostilities, and even then, no real, artificially-made barriers existed between hostile ethnic states or political entities. My core argument is that by utilizing the concept of “enclosures with inclusion” in lieu of “boundaries,” we may better understand indigenous notions of space and territory in central Mexico during preconquest times. Subsequently, we will be able to reconsider, for example, the validity of ethnic entities and ethnic polities in ancient Mexico as firm jurisdictions per se or as ethnic and territorial amalgams, in which ethnic outsider components formed inner enclaves and power bases that served the purpose of continuous intervention of competing powerful altepetl in their local affairs. Adopting the concept of “enclosures with inclusion,” in parallel to the semantics of the powerful representation of unity within diversity in Mesoamerican cosmology that are employed here, could serve us well in identifying both internal and external social and political relationships that evolved within and among the Aztec/Nahua ethnic states and negotiating ethnic groups.

RESUMEN

Investigaciones recientes sobre el Códice Nahua Xolotl han dado lugar a nuevas perspectivas sobre lo que eran “límites” en el pensamiento náhua durante la época precolombina. El presente artículo propone que nuestro concepto occidental moderno de fronteras y fronteras políticas era ajeno a las antiguas sociedades mexicanas y a los estados de la época azteca, en general. En consecuencia, el artículo tiene como objetivo añadir un ángulo novedoso en nuestra comprensión de las nociones de espacio, territorialidad y límites en la cosmovisión indígena en México central durante los tiempos precolombinos, y sus repercusiones para las relaciones sociales y políticas internas que evolucionaron dentro de los estados étnicos nahua-acolhua (altepetl) hasta la primera mitad del siglo diecisiete. Además, siguiendo el ejemplo del Codex Xolotl, el artículo reconsidera la validez de entidades étnicas y políticas en el México antiguo y afirma que muchas de estas unidades y confederaciones eran amalgamas étnicas y territoriales, en las que los componentes de los forasteros étnicos formaban enclaves internos y bases de poder. Sostengo que la conceptualización única que se denomina eran “cercos con inclusión”, que funcionaban como límites porosos e inclusivos hasta bien la era de la formación de la llamada Triple Alianza. La justificación profundamente arraigada en el concepto de cercos con inclusión no era segregar, sino, por el contrario, dar cabida a los grupos étnicos y pueblos recién llegados.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to extend my deepest appreciation for the ongoing commitment and resourcefulness shown by Davide Tamburrini, a Ph.D. student from the Universidad Complutense in Madrid (UCM), with whom I have been working together on the Corpus Xolotl project for the past eight months, at the University of Haifa. Without his intimate involvement in the project, this article would not have materialized. I am also forever indebted to Jerry Offner for initiating me into the Corpus Xolotl's treasures, and to Fritz Schwaller for constantly encouraging me to “think big” on this theme. I also acknowledge the generous financial support lent to this project by the Israel Science Foundation (ISF). I am also indebted to the curator Laurent Hericher and his staff at the BNF at Richelieu-Louvois, Paris, for their generous assistance during my research there.