On February 22, 1812, partially in response to verses like these, an Indigenous army 1500 strong attacked León de Huánuco, a colonial city in the central highlands of the viceroyalty of Peru.Footnote 1 Though bearing only clubs and slings, the army overwhelmed the Spanish sentinels and summarily ransacked the city, specifically targeting residents of European birth (peninsulares). Not only did the rebels leave American-born (creole) residents alone, but they allowed several creole authorities to join and help lead the rebellion. One week later, the army had grown to 5,000 Indigenous and mestizo members, and it operated under the direction of three main leaders: Juan Josef Crespo y Castillo, a creole of modest means who had previously served in the cabildo of Huánuco; José Rodríguez, a mestizo man from Chalhuacocha, just three miles from Huánuco; and Norberto Haro, an Indigenous alcalde (councilman) from Huánuco whose daughter's godfather was Crespo y Castillo.Footnote 2 The ethnic diversity of the leadership reflected the work of other leaders who had played less visible but fundamental roles in the movement, namely bilingual friars. Thanks in part to these men of the cloth, the insurgent army had achieved a degree of unity, albeit not a great one, across ethnic lines. In a region in which some 53.5 percent of the population was Indigenous, 38 percent mestizo, and just 8 percent creole, such unity was essential for a popular movement.Footnote 3

On March 4, the new army, now bearing standards fashioned from paintings in Crespo y Castillo's own living room, attacked the nearby city of Ambo.Footnote 4 Again, they drove all Spanish residents from the area. Like revolutionaries in Mexico and Argentina, they celebrated the victory with chants of (questionable) loyalty to King Fernando VII, but the celebration did not last long. The rebellion was just spreading to the province of Huamalíes when Viceroy José Abascal, who ruled Peru, as Mónica Rickets writes, “in a quasi-dictatorial manner,” dispatched the Intendant Governor José González de Prada and an army of 600 well-armed soldiers to subdue the rebels.Footnote 5 With memories of the Tupac Amaru and Tupac Katari rebellions (1780–82) still relatively fresh, Spanish authorities acted quickly to prevent another regional movement.

They succeeded. On March 18, after some fruitless negotiations with the insurgents, González de Prada and his troops routed the rebel army in a bloody confrontation near Ambo that left some 500 Indigenous and mestizo participants dead; the Spanish forces lost only one man.Footnote 6 González de Prada later marched to Huánuco to reestablish Spanish authority and preside over the tedious process of interrogating local residents and identifying the leaders and motives of the rebellion. The paper trail has become a valuable collection of primary sources from the uprising. Unfortunately, Spanish voices and perspectives far outweigh those of Indigenous participants.Footnote 7

In scholarship, the Huánuco Rebellion has received scant attention, especially from historians in the United States, yet it raises important questions about patriotism and pan-ethnic unity in Peru's era of independence. With the exception of some nationalist writers from the 1960s, historians generally regard Peru as a royalist stronghold plagued by ethnic divisions.Footnote 8 In 1815, Simón Bolívar referred to the region as “without a doubt the most submissive” to the Spanish crown, and in 1823 he wrote that “discord, misery, discontent, and egoism reigned everywhere.”Footnote 9 Reasons for this situation are not hard to find. Most obviously, the Tupac Amaru uprising of 1780, which, as Charles Walker argues, spiraled into a bitter war between ethnic groups, led many creoles and local leaders to fear Indigenous mobilization and thus to remain loyal to Spain well into the 1820s.Footnote 10 The mistrust was mutual. As Cecilia Méndez has demonstrated, some Andean communities preferred Spanish rule to that of local creoles.Footnote 11

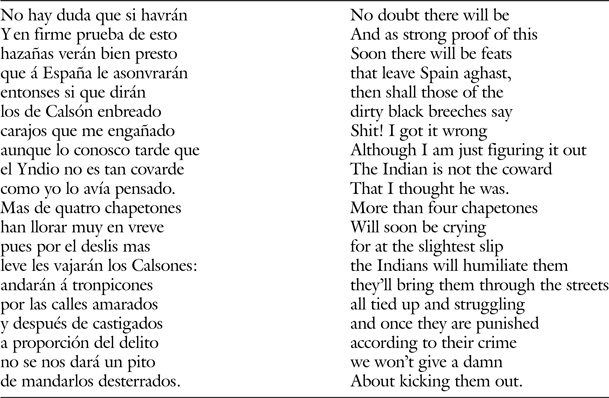

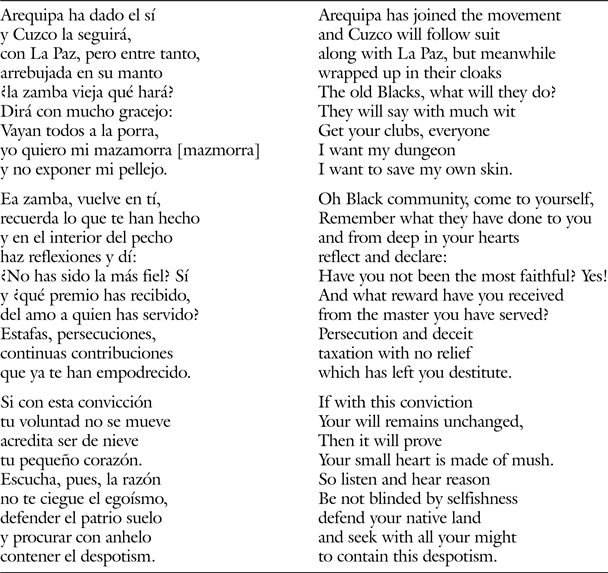

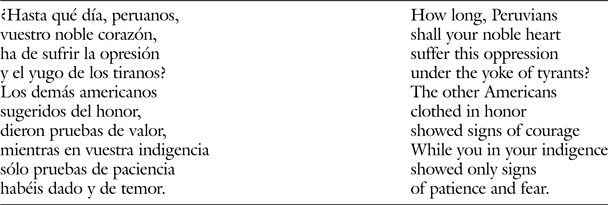

For the friars of Huánuco, however, this tension did not appear insurmountable. Records from González de Prada's investigation repeatedly mention the circulation of papeles seductivos (seductive papers) or pasquines (leaflets) that included pro-independence and anti-Spanish verses, which bilingual friars wrote, translated, and distributed widely; one is reproduced in the epigraph. As Marissa Bazán Díaz points out, “Most of these leaflets were written in Quechua and read out loud to local communities so that illiterate residents could also be privy to their content.”Footnote 12 Using these materials, rebellious friars promoted an early vision of Peru as a place for everyone but outsiders.

The leaflets also underscore the potential of friars as intermediaries in colonial society. In recent years, historians have emphasized the fundamental role of bilingual intermediaries between Spanish authorities and Indigenous communities. Gabriela Ramos and Yanna Yannakakis, for example, describe Indigenous and mixed-race intellectuals as the “fulcrum” or “lynchpin” of society.Footnote 13 These metaphors also apply to bilingual churchmen. Nancy Farriss describes Dominican friars in Oaxaca as “the midwives of the new colonial society taking shape, as much agents and brokers as mere translators.”Footnote 14 Similarly, William Taylor has written that “parish priests occupied critical intersections between the majority of rural people and higher authorities.” These men of the cloth, he explains, could effectively represent the Catholic king to local populations and at the same time serve as defenders of Indigenous communities.Footnote 15 Often, they helped legitimize the Spanish state in the eyes of the people, yet they also had tremendous potential to “oppose, as well as support, [state] power.”Footnote 16

Notwithstanding Peru's reputation as a bastion of royalism, the pasquinades of the Huánuco Rebellion demonstrate some friars’ engagement with notions of independence, and González de Prada's investigation illuminates their efforts to spread these ideas across the central Andes. To borrow a metaphor from F. Javier Campos y Fernández de Sevilla, the leaflets circulated by the friars created a “trail of gunpowder” through the region that exploded in late February of 1812.Footnote 17 The proliferation of additional papeles seductivos in Huamanga in May of the same year, as well as the large 1814 uprising in Cuzco, in which priests also played a leading role, further attest to strong anti-Spanish movements in the Andes during the early era of independence.

Although the iron-fisted Abascal managed to crush these movements, they still rocked the viceroyalty. Moreover, even though many residents, regardless of ethnicity, remained wary of the social implications of independence, they nonetheless forsook colonialism. In Huánuco, divisions between creole and Andean rebels did weaken the movement, but the uprising demonstrates that many residents were willing to fight for independence, or at least home rule, more than a decade before outside armies defeated Spanish forces.Footnote 18 The incendiary leaflets of the rebellious friars exemplify this important precursor to Peru's history of independence.

Following the attack on Huánuco, authorities quickly identified the papeles seductivos as catalysts of the rebellion. While González de Prada was still in Ambo, authorities in Cerro de Pasco, a city just south of Huánuco, arrested Mariano Cárdenas, a trader from Cuenca, and Manuel Rivera, a silversmith from Quito, both of whom had previously been denounced as alsados, reboltosos, and promovedores de sublevaciones (insubordinate, rowdy individuals and promotors of uprisings) because of a “patriotic” song they had allegedly sung. In response to the authorities’ probing, Cárdenas testified that during the previous Feast of Corpus Christi he and a group of friends had indeed gathered at Rivera's house, and, after imbibing generous quantities of chicha and aguardiente, they began playing the guitar and singing. Because of the effects of the chicha, Cárdenas declared, he could recall only a few of the lines: “El chapetón y el criollo, se unieron en Amistad, con la misma intimidad, que un Gavilán con un pollo” (The chapetón [derogatory name for Spaniards] and the creole united in friendship, with the same closeness as a hawk and a chicken). The lyrics, of course, were satirical. In the Andes, the hawk that the singers spoke of was a known predator of chickens.Footnote 19

The Spanish authorities were not pleased. Immediately, they demanded to know more about the author of this song. Cárdenas's roundabout responses revealed that a Mercedarian friar from Quito by the name of Mariano Aspiazu had penned the lines, and that this friar currently resided in Huánuco. Cárdenas also admitted that he and Aspiazu had discussed news from Lima about the revolutions in Quito, Buenos Aires, and Chile. Sensing that his answers would displease his interrogators, he hastened to add that when he realized the lines were “not good,” he burned them, and that, in reality, he hardly knew Aspiazu at all.Footnote 20 Authorities, however, now had a lead.

Following Cárdenas's interrogation, they questioned Manuel Rivera, who denied the charges of insurrection and blamed the incident at his house on Cárdenas and the effects of the chicha. Cárdenas, he said, had shared the verses with the group as they enjoyed music and drink. The author, Aspiazu, had originally distributed the verses from Huancayo. Because of the chicha, Rivera stated, he did not remember the words at all. When asked if he had had “secret conversations” with Father Aspiazu, Rivera indicated that the friar had told him, among other things, that he was coming to “defend the creoles because the Europeans wanted to enjoy the jobs [positions of authority] for themselves, leaving nothing for the Americans.” Rivera further stated that he had in his possession some 25 or 30 décimas (ten-line stanzas) that Father Aspiazu had sent from Ulcumayo with the request that Rivera copy and distribute them in the streets and churches. In his own defense, Rivera proudly explained that he had not complied with the friar's request.Footnote 21

Authorities summoned Cárdenas and Rivera for questioning multiple times, along with others who had participated in the incident on the day of Corpus Christi. Their interrogations culminated with questions about Mariano Aspiazu, his close contacts in the region of Huánuco, and the nature of the décimas. In a follow-up interrogation, Cárdenas admitted that the friar had indeed sent him some poems from Ulcumayo, and that after receiving them he had held onto them for ten months.Footnote 22 While the interrogees obviously wanted to distance themselves from charges of subversion, their answers pointed Spanish authorities to a veritable network of subversive friars and creoles throughout the central Andes, which for months had achieved unity and solidarity by meeting together and circulating secret, satirical, and seditious poems.

The circulation of these papeles seductivos from Quito and Cuenca south to Huánuco and Ulcumayo (and perhaps beyond) symbolically challenged the established circulation of documents between Spain and Lima, and, in turn, the established colonial order. In his analysis of “the lettered city” in colonial Latin America, Ángel Rama describes the crucial role of written documents in linking urban centers, such as Lima, to the royal courts of Spain. The Spanish monarchy used the constant flow of documents almost like a leash as it sought to establish its vision of “order” and hierarchy in the New World.Footnote 23 The friars’ secret circulation of their own documents challenged the established order, especially considering the messages that these documents bore. Yet more threatening than the documents themselves was the stance of the friars. Rama further explains that because of its dependence on written documents, the Spanish crown had come to rely heavily on a permanent class of urban letrados or educated administrators, which included priests and interpreters. These letrados “were defined essentially by their use of writing,” and while their work included myriad legal, administrative, and religious texts, “a great many wrote amateur verse.”Footnote 24 The discovery of the friars’ seditious verses around Huánuco indicated the rebellion of some of the crown's most essential letrados.

Long-term motivations for this rebellion can be traced, in large measure, to the Bourbon Reforms of the mid to late eighteenth century. As D. A. Brading has explained, the Bourbon kings sought to regain administrative and economic control of the colonies from the lawyers, landlords, merchants, and churchmen—the creole elite—who had come to wield tremendous power. To do so, they implemented “radical reform[s] in civil administration” that often involved removing creoles from positions of authority and replacing them with Spaniards.Footnote 25 (Hence Friar Aspiazu's comment about the Spanish wanting all the jobs for themselves.) Clergymen were handed a particularly bitter cup. Influenced by the Enlightenment and committed to science, the Bourbon kings sought diligently to curtail the power of local priests. As William Taylor writes, “In the Bourbons’ vision of a new order, the function of parish priests beyond the altar and the confessional was reduced and largely undefined.” Specifically, the Bourbon reformers withdrew royal stipends for priestly services and treated priests “more as meddlers and obstacles to colonial integration than as intermediaries and agents of the state.”Footnote 26 Their attitude toward the church was not unique. Thomas Jefferson wrote that “a priest-ridden people” would be ill-prepared to maintain “a free civil government.”Footnote 27 Among Enlightenment thinkers, anticlericalism abounded. In the Spanish colonies, it would prove fatal to Spanish control.

While the use of newer, scientific methods of government may have helped the Bourbons manage, revive, and modernize their colonies, it ignored the fact that priests remained, to borrow Taylor's words, “the literal and figurative interpreters of [the] imagined order.”Footnote 28 By reducing their role, the Bourbon kings unwittingly began to weaken a linchpin that, for nearly 300 years, had secured the obeisance of the Spanish colonies with remarkable consistency. They likewise “[cut] themselves loose from divine purpose.”Footnote 29 The eventual result in many cases was popular, priest-led rebellion. To put a twist on Nancy Farriss's observation about intermediaries in early colonial society, priests now became “the midwives of the new [independent] society taking shape, as much agents and brokers as mere translators.”Footnote 30

An important trigger for priest-led uprisings was Napoleon's 1808 invasion of Spain and the abdication of Fernando VII.Footnote 31 As Roberto Breña has written, the absence of a legitimate ruler “opened the way for . . . a profound ideological transformation affecting the whole mundo hispánico.”Footnote 32 Mónica Rickets adds that the political shock in Spain ushered in “a new era of public political debate . . . in the Spanish world.”Footnote 33 In this period of change, the Cortes of Cádiz led the process of liberal reform by ending Indigenous tribute, granting citizenship to Indigenous communities, softening social hierarchies, and reducing (yet still recognizing) the role of the Church.Footnote 34 Certainly, not all authorities in the Americans accepted these reforms. In Peru, Viceroy Abascal rejected the 1812 Cádiz Constitution and tried mightily to limit its application.Footnote 35 Yet priests played a fundamental role in receiving, disseminating, and discussing this information. Speaking of these “liberal years, 1808–1814” in the Andes, Paulo Lanas Castillo notes that information coming out of Cádiz was “channeled through civil and ecclesiastical authorities,” and that priests often adopted a “pedagogical role” by translating information into Aymara and Quechua and announcing it to local communities in plazas and churches.Footnote 36

For disgruntled priests, the absence of a legitimate ruler in Spain provided room to pursue their own agendas. As Marissa Bazán has written, some priests seized the moment to introduce their own ideas to Andean communities and fill, to an extent, the power vacuum themselves. Since Huánuco did not have a printing press until 1828, news during the late colonial period spread mainly by word of mouth and by handwritten leaflets.Footnote 37 Using both forms of communication, rebellious friars could spread the word that the time had come to cast out the undesired peninsulares. Joëlle Chassin has emphasized the “war of information” that began in Peru once Napoleon invaded Spain. Authorities in Lima tried to control the official news that reached the rest of the viceroyalty, yet they failed entirely at controlling the “clandestine texts,” including pasquinades, broadsides, and songs, that circulated widely among the elite and popular sectors of society.Footnote 38 In Huánuco, friars produced many of these clandestine texts.

Of course, not all priests and friars favored rebellion or independence. As Jeffrey Klaiber points out, historians sometimes exaggerate the presence of pro-independence clergy in the Americas. In his estimate, “of the 3000 priests in Peru on the eve of independence, possibly only ten percent actively supported the cause.”Footnote 39 In Huánuco in 1812, the proportion of pro-independence priests appears slightly higher, perhaps because a few rebellious friars such as Aspiazu had recently relocated from Quito. In his 1793 Guía, creole official Hipólito Unanue recorded that Huánuco had nine secular clergy and 30 friars.Footnote 40 In the rebellion of 1812, at least five friars played leading roles.Footnote 41 In the Augustine convent of Huánuco, which accommodated ten to 12 friars, Marcos Durán Martel, who emerged as the “spiritual leader” of rebellion, used his own cell to meet with emissaries from Andean towns, make copies of subversive literature, and plan the initial attack. His fellow Augustine Ignacio Villavicencio worked with him.Footnote 42

Although friars had potential to oppose state power if they desired, their influence over Andean communities was not without limits. At the turn of the century, Huánuco, which included the city itself and 17 surrounding pueblos, had approximately 18,826 inhabitants.Footnote 43 Even with their prolific production of leaflets, the handful of rebellious friars could reach only so many people. Consequently, they worked through Andean alcaldes, such as Norberto Haro. Since, as Chassin points out, alcaldes often translated written documents into Quechua for their communities, they too served as crucial mediators of information.Footnote 44 Prior to the attack on Huánuco, Friar Durán Martel wrote letters to the alcaldes of at least 12 pueblos calling on them to arm their communities and prepare for an assault on the city.Footnote 45 Many alcaldes answered the call; some did not.

In an effort to persuade Andean alcaldes and communities to rise up, the friars tried to channel local grievances into a larger anti-Spanish movement. As scholarship on the 1812 uprising indicates, most huanuqueño rebels directed their ire at particular Spanish authorities; full-fledged independence was not their immediate goal. Just prior to the uprising, for example, authorities in Lima had prohibited the sale of tobacco and established other economic restrictions that significantly affected creole, mestizo, and Indigenous residents but exempted the city's Spanish elite, who in most cases had close ties with authorities in Lima.Footnote 46 Durán Martel, for one, had a tobacco plantation.Footnote 47 Furthermore, the powerful Llanos family of Huánuco had earned the hatred of many residents.Footnote 48 As the royalist friar Pedro Ángel Jadó admitted, anger against Europeans “was inevitable,” given the corrupt and nepotistic practices of the region's merchant elite.Footnote 49 Since local animosity mattered more, overall, than political ideology, this uprising calls to mind those of the previous century in which, to borrow William Taylor's words, disgruntled rural communities made “good rebels but poor revolutionaries.”Footnote 50 Yet in this case, events abroad furnished fractious friars with an ideology of home rule.

The difference between late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century uprisings is evident in the pasquinades that circulated in each era. This “honored form of colonial protest,” as Sarah Chambers describes it, helps reveal the ideas that circulated before armed conflict broke out.Footnote 51 Admittedly, it is impossible to know exactly what people thought when they read or heard these verses. Yet in Huánuco, the friars’ considerable efforts to spread these leaflets to Andean pueblos suggests a legitimate belief that the pueblos would be persuaded by their messages. Hence, Spanish authorities described the leaflets as “seductive papers.” One official even referred to the friars’ efforts as “the dark scheme of the pasquines.”Footnote 52 To borrow the words of Gabriel García Márquez, these leaflets constitute a “less deadly, but no less damaging” manifestation of political unrest that served as a “prelude” to the violence.Footnote 53

In the pasquinades of the late eighteenth century, authors mainly directed their discontent at particular authorities. In the relatively mild 1780 uprising in Arequipa, which occurred just a few months before the outset of the Tupac Amaru Rebellion, rebels directed a verse at Balthazar Sematnat, the corregidor who oversaw the hated Bourbon-era institution known as the repartimiento. Through the repartimiento, local Spanish officials could force Andean communities to buy products they did not want and at prices they did not accept.Footnote 54 “Take care of your head,” the 19-line pasquinade began, “And also your companions’ / The señores customs officials, / Who without charity / Have come to this city / From distant foreign lands / To tear out our entrails.” The verse then called on the people to take the lives of the offending Spaniards.Footnote 55 Notably, other verses responded to such calls to arms by denouncing the rebels and their ideas.Footnote 56 Both sides, however, assumed ultimate loyalty to Spain. As another rebellious verse declared, “Long live the King / And death to the evil within his government.”Footnote 57

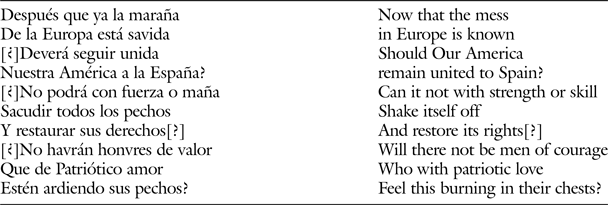

By contrast, in the 50 or so pasquinades that have been preserved from Huánuco, the friars focus largely on events abroad and their implication for the Americas. The following verse makes their intention clear.Footnote 58

When these friars spoke of “another government,” the only characteristic they explained clearly was that it would be free of Spaniards. They were not clear about how relations between creole and Indigenous citizens would change, yet their behavior demonstrates that they intended to be in charge. In his study, Castleman applies Mark Thurner's description of the creole elite's “post-colonial predicament” to the Huánuco Rebellion: the elite, including friars, sought “to integrate Andeans into a liberal Peruvian republic, [yet] still maintain [their] hold on power.”Footnote 59 But in their verses, of course, the friars did not articulate this predicament. Rather, they dwelt on something they hoped everyone could agree on, namely hatred of Spaniards.Footnote 60

Although none of the pasquinades include an author's name, Father Aspiazu likely wrote many of them. As Castleman notes, he “had been banished from his native Quito in 1809 for similar activities,” and Álvaro Segovia Heredia describes him as “perhaps the most experienced panfletista (pamphleteer) among [the subversive] friars” of Huánuco.Footnote 61 Even Jadó, a Spanish priest from Huariaca (to the south of Ambo), who had nothing good to say about anyone from Huánuco, recognized Aspiazu as a formidable man of letters. In his long account of the uprising, written as a series of epistles to Bartolomé de las Heras, archbishop of Lima, Jadó referred repeatedly to Crespo y Castillo as “this old idiot.” In Jadó's opinion, José Rodríguez and his family were “inferior men (mozos) of no importance.” Friars Marcos Durán Martel and Francisco Ledesma, who also played leading roles in the rebellion, appear in his account as, respectively, “a moron” (un estúpido) and “a wretch” (un miserable). Jadó even described Alfonso Mejorada, the subdelegado of Panatahuas and fellow European, as “a good man but controlled by his wife”—a low blow in machista circles. But of Aspiazu he wrote, “He is no dummy,” and with his verses, he did “much for the rebellion.”Footnote 62

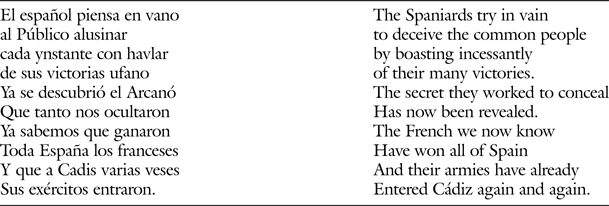

Although Aspiazu and other subversive friars were, as Rama suggests, amateur writers, their work reveals skill with the pen, awareness of a diverse audience, and an understanding of events abroad. Besides addressing the situation in Spain, several décimas, including the following one, speak of rebellion in nearby regions and assume that Peru will follow suit.Footnote 63

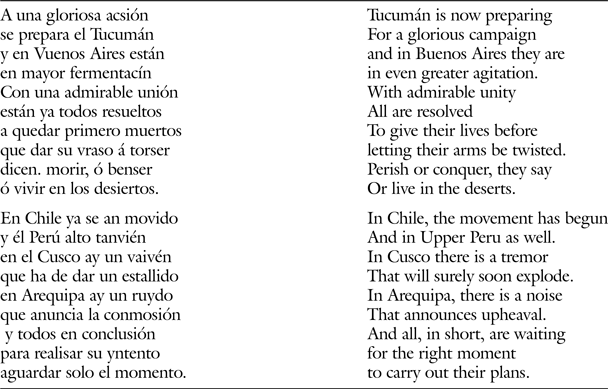

Through verses like these, the friars depicted an empire rocked by a series of explosive rebellions. One after another had already gone off; now it was Peru's turn. This outlook sets Huánuco apart from Andean rebellions of the previous century. Even if local grievances remained the primary motivation, the friars saw in events abroad solutions to local troubles. The times were a-changing, as the following verses show.Footnote 64

While these verses were certainly designed to appeal to creoles, they also sought to reach Andean communities. Some verses, for instance, spoke of the strength of the region's Indigenous groups. In response to the question “Will there not be men of courage?” (cited in the epigraph), the friars respond that there surely would be such men.Footnote 65

In a region in which over half the population was Indigenous, verses such as these represented crucial ligatures in the friars’ effort to draw different ethnic groups together. Perhaps surprisingly, some verses also reached out to Peruvians of African descent. On several levels, these lines reflect the racism of the day, but they also represent an effort at unification. Black Peruvians, free and enslaved, made up less than one percent of the population in the central Andes.Footnote 66 Strategically, their participation was not necessary for the success of an independence movement. Nevertheless, the friars sought to include them. This effort, which informs the following verses, would suggest that the friars’ desire for unification was not just opportunist but, at least to an extent, truly nationalist.Footnote 67

In Peru, unity across ethnic lines was a tall order, especially after the Tupac Amaru and Tupac Katari rebellions. In the latter, Aymara struggles for self-rule put Andean communities at odds with Spanish officials and even with Indigenous caciques.Footnote 68 In the case of Tupac Amaru, a Quechua-speaking cacique by the name of José Gabriel Condorcanqui and his wife Micaela ignited a rebellion largely because of the onerous policies that the Bourbons had imposed on Andean communities.Footnote 69 Although Condorcanqui tried to enlist the aid of creoles and mestizos, his movement was permeated with neo-Inca nationalism.Footnote 70 His own choices to take the name Tupac Amaru II after the Inca leader executed by Viceroy Toledo in 1571, and to make public declarations in Quechua, reinforced this focus. As the movement grew, warring factions of Indigenous and non-Indigenous groups became increasingly polarized and violent. In fact, the treatment of Andean communities during the Tupac Amaru era may be a precedent for a repeating phenomenon in Latin American history in which, in the eyes of the state, Indigenous identity automatically becomes a sign of insurgency, despite some groups’ obvious innocence, neutrality, or loyalty.Footnote 71

Importantly, the friars did refer to their audiences as “Peruvians,” despite recent scholarship that emphasizes the term ‘americanos’ in Latin America's era of independence. Building on Benedict Anderson's idea of “creole pioneers,” John Charles Chasteen has examined the way in which patriots in the early 1800s used the terms América and americanos to achieve “the crucial extension of the definition of Sovereign People from whites only to anyone born in América,” and to construct “a binary divide separating all americanos, on one hand, from europeos (Europeans) on the other.”Footnote 72 Additionally, Chasteen and others have argued that use of “national identifiers (Mexican, Argentine, Brazilian, etc.) . . . increased only after independence.”Footnote 73

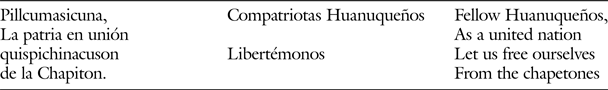

The documents from Huánuco point to a somewhat different conclusion. The friars who wrote seditious pasquinades fit the definition of creole pioneers, and in some ways they did see América as a coherent region. At the same time, they did use the term peruanos, which suggests a vision of their communities as related to but separate from neighbors in Chile, Buenos Aires, Upper Peru, and beyond. Given that Aspiazu and other friars were from Quito, their references to peruanos may refer to the inhabitants of the entire viceroyalty, yet in some verses, quiteño friars also take the position of outsiders who, in the age of revolution, have come to wake up the sleeping Peruvians. Either way, this vision of peruanos included residents of many ethnicities and castes in a way that broke with the colonial system. As Campos y Fernández argues, the friars’ vision of unity against Spaniards gave the Huánuco Rebellion a “distinctly Peruvianist character.”Footnote 74 For their part, Andean pueblos around Huánuco seemed cautiously open to the idea.

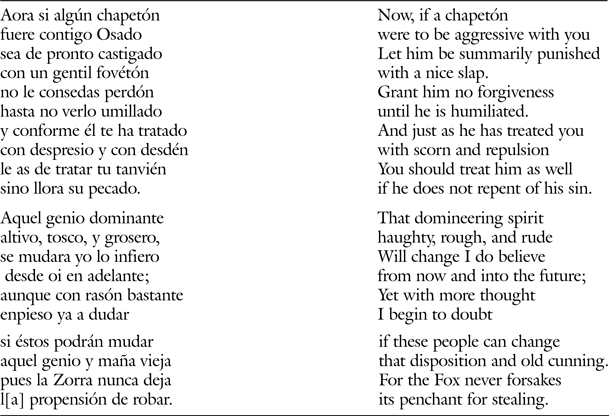

Thus, well before Peru won independence in 1824, a nascent sense of Peruvian identity and boundaries was developing. In one additional décima from Huánuco, the friars’ sought to inspire that bold spirit.Footnote 75

Given the frequent mention of papeles seductivos in the Spanish investigation, the décimas that survive in the archival record must be only a tiny fraction of those that circulated throughout the Andes. Yet those that remain provide valuable examples of the friars’ efforts to challenge peninsular power. Friar Aspiazu was the most prolific panfletista, but several other men of the cloth played central roles in the production of these leaflets. Francisco Ledesma, the Mercedarian from Lima, whom Jadó had written off as a wretch, helped write and distribute them. In his defense before Spanish authorities, Ledesma, his lawyer, and witnesses testified that the friar had not attended any subversive meetings.Footnote 76 Yet he was clearly involved.Footnote 77

The Spanish investigation also illuminated the leading role of Marcos Durán Martel. Despite Jadó's claim that Father Marcos was a moron, it is clear that Durán Martel helped to organize the attack and circulate the seditious leaflets. In one confession, a young man named Pedro Tello testified that he had brought the “seductive leaflets” from Father Marcos to the military leader José Rodríguez. In a mixture of contrition and self-defense, Tello declared that he had done so only because he was young and escaso de luces (dimwitted), and that Father Marcos had ordered him to do so with the promise of payment. Tello added that he had not noticed the content of the leaflets, nor had he realized that Father Marcos was not the “man of character” and “sincere virtue” that he appeared to be.Footnote 78 Tello's declaration of innocence, like others, appears questionable, but it also indicates the skill of the subversive friars at maintaining normal appearances of piety and orthodoxy.

In another confession, Narciso Ponce testified that Father Marcos had hired him to make some crucecitas (small crosses). During a visit related to this commission, Ponce reported, the friar had declared that he wanted to punish the chapetones because “they harassed, hit, and mistreated the creoles whenever they wanted, and they only came to Huánuco to make money.” The huanuqueños, Durán Martel had added, “were nothing but tributaries of the chapetones, and these chapetones operated with cunning, defiled the ladies, and made themselves wealthy gentlemen with the sweat of the creoles.” According to Ponce's testimony, Father Marcos claimed to have orders from Juan José Castelli, the revolutionary from Argentina, to “spread the word about what was happening to the chapetones [in other regions] so that they [in Huánuco] could be free of their tyranny.” Ponce further testified that Father Marcos had said that he and other priests were making bullets and cutlasses, preparing rifles, and hiding a barrel of gunpowder.Footnote 79

The relationship between Castelli and Durán Martel was probably limited. Yet as Marissa Bazán argues, far more important than real contact with Castelli were the rumors of Castelli. When they wrote leaflets in Quechua to be read aloud to Andean pueblos, rebellious friars could mix news from abroad with rumors that might appeal to their audiences. These rumors, as well as the leaflets themselves, “proved very difficult [for Spanish authorities] to control,” especially in the absence of a printing press to counter them. One important rumor held that Castelli was a reincarnation of an Inca king who was coming to liberate the Andes.Footnote 80 This myth came in multiple versions. As Joëlle Chassin argues, every group adopted the most useful part of Inca legend for itself.Footnote 81 Notably, however, the myth does not appear in the pasquinades. Rather, González de Prada's investigation suggests that other creole leaders, most notably Domingo Berrospi, promoted the idea in an effort to manipulate Andean communities.Footnote 82 While the idea of unity presented in the pasquinades was misleading, rumors of Castelli as a reincarnation of the Inca suggest a more direct effort from some creoles to beguile and exploit Andean pueblos.

While he personally preferred making bullets to writing décimas, Father Marcos oversaw the drafting, copying, and distribution of papeles seductivos. Ponce also testified that the friar had paid him to draft several pasquinades and that Father Marcos had worked closely with José Rodríguez in the distribution of the material. Ponce also mentioned that Durán Martel had relied on his fellow Augustine Ignacio Villavicencio to edit the original verses, “adding commas and dashes.”Footnote 83 The fact that Durán Martel treated this subversive literature with the same level of energy and secrecy that he devoted to bullets and swords attests to his belief in its importance for the success of the uprising.

Authorities also arrested Friar Villavicencio, and like other defendants the friar presented evidence of loyalty to Spain. Many friends testified that Villavicencio was not “díscolo” (wayward), nor had he been seen with people “of bad reputation.” Rather he had always been “religious” and “recogido” (reserved).Footnote 84 The colonial record even includes the conclusion of a sermon that the priest delivered on December 8, 1811, which had, according to one witness, “filled the whole congregation with holy emotion.” In the sermon, Villavicencio entreated the Virgin Mary to “cast from us all seduction.” He continued, “[Remember] that the Sovereign Fernando is an unfortunate branch of the House of Bourbon, who suffers the tyrannical usurpation of the enemy of humankind. Wilt thou comfort him in his afflictions and his captivity. Wilt thou sustain the faith of his heart.” Shifting the subject of his prayer to Spain itself, the friar added, “Look upon the mother Spain, fugitive and wandering, searching for refuge from her enemy. . . . May those generous warriors sally forth and, armed with thy name, recover their losses and return to thee the sweet song that thou art the glory of Spain and the honor of the most faithful Peru.”Footnote 85

Evidence of this kind raises questions about the friars’ political position. Was the loyalty all fake? Were the friars wolves in sheep's’ clothing whose piety was really patriotism? It is difficult to know their personal feelings, but, as John Charles Chasteen explains, loyalty to Fernando VII during the liberal years was not incompatible with rebellion from Spain, since after deposing Fernando, Napoleon had installed his brother as king.Footnote 86 Thus, declarations of loyalty to Fernando likely did have some sincerity. Yet at the same time, the exclusion of priests and friars resulting from the Bourbon reforms had instilled in many clerics a legitimate desire to be rid of the Spanish. When Friar Villavicencio beseeched the Virgin to “cast from us all seduction,” the idea of seduction was based on highly fluid notions of right and wrong, loyalty and patriotism.

For his part, Father Villavicencio seems to have become increasingly committed to the idea of armed rebellion. In the Spanish investigation, witnesses testified to his friendship with Durán Martel.Footnote 87 Furthermore, the devotional sermon of December 1811 is not his only writing preserved in the colonial record. In his own deposition, the friar admitted that he was the author of the following bilingual verse.Footnote 88

Immediately after recalling the lines, Friar Villavicencio argued that the idea of an uprising had never crossed his mind because his verses were meant only to manifest discontent with the end of the tobacco industry. He also declared that he knew nothing about the rebellion until he heard the general news on February 22 that “the Indians were coming.”Footnote 89 Villavicencio's claim of innocence is obviously false and, from the native participants’ point of view, quite cowardly. The friar's desire to instigate an uprising is clear. By translating political messages into Quechua—or into a mix of Quechua and Spanish—he and other clergymen helped bridge the linguistic gap in the system of castes. In so doing, their movement came closer to subversion in the literal sense, a true “turn from below.”Footnote 90

The position of the friars as linguistic and cultural intermediaries made them highly effective insurgents. As several accounts confirm, their verses, written in Spanish and Quechua, were the main tools that rebel leaders used to galvanize Indigenous communities into action.Footnote 91 Diego García, the subdelegate of Huánuco whose ties with elite merchants epitomized everything residents hated about local Spanish authorities, explained in his report of the initial uprising that the pasquinades “were seen daily” throughout the region despite his efforts to stifle their circulation. Through them, the authors influenced “con sigilo [covertly] the feelings of the residents.”Footnote 92 Moreover, several witnesses testified that rebel leaders had distributed the subversive leaflets throughout Andean pueblos. One resident testified that prior to the attack on Huánuco, “José Rodríguez of Chalhuacocha had made a trip to all the pueblos of Panatahuas and Santa María del Valle with the objective of seducing them by means of some papers so that, together, they would come to . . . destroy the judges and chapetones.” The witness added that another rebel, Antonio Espinosa, had made a similar trip.Footnote 93 Spanish militia leader Francisco Ingunsa confirmed these accounts, testifying that large numbers of subversive pasquines were written in Quechua (en lengua india), and that Indigenous men had distributed these leaflets throughout Santa María del Valle, Pillao, Acomayo, and other pueblos.Footnote 94

The pasquinades also plagued Spanish authorities in the city of Huánuco itself. Ingunsa testified that on January 20, when the people of Huánuco celebrated the feast of St. Sebastian, their city's patron saint, residents “began posting pasquinades against European residents” urging the people to “be through with them.”Footnote 95 Similarly, Jadó noted that Huánuco in the days preceding the uprising was in a state of “fermento fatal” (terrible uneasiness). “Secret meetings of Indians” went on right under the nose of Spanish authorities. “Every morning seditious pasquinades appeared, threatening [a large-scale uprising], and the slander against chapetones was increasingly bold.”Footnote 96 In early February, leaflets appeared that warned Europeans to leave. Instead of leaving, however, local authorities offered a reward of 100 pesos for information regarding the authors of these messages, and they ordered European and loyal residents, including some soldiers, to prepare for a possible invasion.Footnote 97

The invasion came, and the Spanish were not prepared. As several witnesses recalled, at around twelve o'clock on February 22, Indigenous inhabitants from several pueblos around Huánuco sallied forth from the hills and haciendas and began their attack. While most Spanish officials managed to flee, a few were brutally killed. Some witnesses recalled that “it seemed to us that this was the Day of Judgment.” In the home of the Spanish colonel Antonio Echegoyen, “they didn't even leave spider webs.”Footnote 98 After the initial attack, the potential for an organized, united movement almost dissolved when the creole rebel Domingo Berrospi, in an effort to gain control of the Andean army and mask his rebellious intentions from Spanish authorities, decided to imprison and secretly execute José Contreras, a mestizo who had led the looting of city.Footnote 99 Not surprisingly, the Indigenous cabildo rejected him as a leader and chose Crespo y Castillo instead. At this point, a united uprising remained a legitimate, if remote, possibility. Yet as Castleman's work demonstrates, rifts between creole rebels, as well as rifts between Huanuqueño townspeople and rural Andeans, continually undermined the movement.Footnote 100

Meanwhile, the distribution of bilingual pasquinades continued. Further testimony indicated that the priests enlisted or encouraged creoles in nearby cities to write, copy, and distribute the leaflets in an effort to spread the fires of rebellion. One document includes accusations against Manuel Queipo and Ramona Lope for “the serious crime of authoring some pasquines and seditious papers, which they posted and spread in [Pasco].” The “nasty and obscene leaflet,” wrote one Spanish official, was designed to “induce and incite an uprising” on the heels of the attack in Huánuco.Footnote 101 Moreover, Pedro Angel Jadó noted that before the violent confrontation near Ambo, the leaders of the rebellion tried to augment their forces by targeting American-born soldiers who served in the colonial army of Tarma. In his words, the clerics sought to “seduce even the troops of Tarma by means of pasquinades which appeared . . . in the barracks, telling the Tarmeños to take up arms against the Europeans, for this was not a war between fellow citizens.”Footnote 102

While translated leaflets may have helped insurgents come together in rebellion, spoken interpretation helped them collaborate in the military movement itself. Juan José Crespo y Castillo and José Rodríguez were both bilingual.Footnote 103 There is less information on Norberto Haro, but he appears to have spoken mainly Quechua because he offered his final confession through an interpreter.Footnote 104 The linguistic abilities and ethnic diversity of these leaders helped hold the movement together, especially in the march from Huánuco to Ambo. Perhaps this march marked one of the greatest moments of ethnic unity since the arrival of the Spanish.

Of course, bilingual ability did not ensure that Crespo y Castillo or Rodríguez would become leaders of the movement. Documents from González de Prada's investigation indicate that Indigenous leaders saw Crespo y Castillo less as a commander and more as a partner. Andean communities had their own alcaldes, made their own decisions, and avenged their own grievances.Footnote 105 In fact, prior to the final confrontation near Ambo, Viceroy Abascal had called on the “seduced [Andean] pueblos,” to cast off the “pernicious influence” of the creole rebels, and González de Prada had offered them peace.Footnote 106 Their quarrel, they suggested, was not with Andean communities. In response, nearly 30 alcaldes who served as spokesmen for their communities wrote to González de Prada justifying their participation in the uprising. “The general harassment that all Indians suffer at the hands of the Europeans is well known,” they wrote, and “this situation [has forced] us to banish all Europeans, that by so doing we might live with a measure of tranquility.”Footnote 107

In response to González de Prada's olive branch, the alcaldes replied, “The peace that Your Honor asks for is not at the present time desirable, for the news has not escaped us that Your Honor is well equipped with all manner of weapons and . . . arms. How, then, are we supposed to believe that Your Honor seeks peace and tranquility, especially when all your auxiliaries are Europeans and when these are known and bitter enemies?” After presenting further doubts of González de Prada's intentions, the alcaldes concluded, “[We must] cut out the cancer of persecution with which these Europeans currently threaten us.”Footnote 108 And with this, they continued their march with the rebel army.

Although many alcaldes signed this letter, certainly not all took this position. As Chassin points out, some alcaldes hesitated to get involved, because in their view the risks of rebellion alongside creole radicals outweighed the possible benefits.Footnote 109 Again, Andean alcaldes and communities acted on their own terms and according to their own interests, but in many cases, they found common ground with the anti-Spanish sentiments in the friars’ pasquinades.

Andean and creole rebels may have shared a common enemy, but they also harbored deep mutual mistrust. Creoles feared an Indian army that they could not control—the return, in other words, of the Tupac Amaru era. As Sarah Chambers argues, many creoles “were ready to take advantage of the opportunity to establish a provisional government once the revolt broke out.” However, they “were unlikely to remain in an alliance unless they believed they had the upper hand.”Footnote 110 Andean participants, for their part, had well-grounded misgivings about creole intentions and commitment to social change. They also understood, quite shrewdly, that Spanish authorities would hold creole participants to a higher level of accountability. In Castleman's words, “Aware that the Spanish colonial regime's attitudes toward them consisted of a strange mix of disdain, condescension, and paternalism, Andean alcaldes most likely calculated that Creole leaders would receive the brunt of the blame and punishment should the Huánuco insurrection end in failure.”Footnote 111 Self-interest and suspicion weakened and slowed the march near Ambo, giving González de Prada's army, which already had the advantage of artillery, even more of an upper hand.

In the aftermath of the slaughter, any remaining unity unraveled. Many detainees argued that they could not have participated in the rebellion because they did not speak Quechua. Josef María Templo testified that he had not spoken with José Rodríguez nor with any rebels because “they spoke in lengua [and] he did not understand them.”Footnote 112 Antonio Espinosa made a similar argument regarding his contact with Crespo y Castillo.Footnote 113 Bilingual friars could not avail themselves of this convenient, albeit baseless, argument, yet some, such as Villavicencio, tried nonetheless to paint the Indigenous rebels as a barbarian horde with which they had nothing to do. For their part, many Indigenous participants, particularly those who joined in the march to Ambo, argued that they were at heart loyal to the Spanish crown and that “the people of Huánuco had deceived them.” Some even returned the goods they had looted—goods the friars had hidden in their convents—as a form of penance.Footnote 114 The speed with which different groups began to accuse each other and declare their undying loyalty to Spain underscores the limits of ethnic unity in late colonial Peru.

Although the clerics of Huánuco tried to deny their involvement, the papeles seductivos stood as material evidence against them, and Spanish authorities held them partially responsible for instigating the uprising. Father Marcos was exiled for life and sentenced to ten years of service in a hospital in Spain.Footnote 115 Villavicencio was turned over to the archbishop of Lima. Aspiazu, the slippery wordsmith, “remained at large for an entire year,” Castleman writes, “before being captured while distributing insurrectionary pamphlets in Cerro de Pasco,” to the south of Ambo.Footnote 116

Spanish authorities reserved capital punishment for the secular leaders who had led the march to Ambo. Crespo y Castillo, Rodríguez, and Haro tried to escape, but the Spanish governor eventually captured them. As further evidence of division between insurgent groups, Andean rebels prevented Crespo y Castillo from fleeing and turned him over to Spanish authorities.Footnote 117 To send a message to local populations, Viceroy Abascal ordered these three secular leaders to be hanged and their bodies left on display.

More than 60 Andean alcaldes paid for their earlier defiance by fulfilling sentences that ranged from two years of labor in the Cerro de Pasco mines to ten years in the Fortaleza de Real Felipe in Callao.Footnote 118 Overall, however, authorities largely treated Andean communities just as these participants had expected—as gullible commoners whom the friars had duped into their service. Pedro Ángel Jadó complained passionately about this interpretation. “I know that [authorities in Lima] will say that [the Indians] were seduced,” he wrote, but before authorities pardon them, they “should come to Huánuco and see what the Indians have done to the city and the haciendas.” What is needed, he argued, is harsher punishment: “The Indian who turns insurgent will be so forever unless he is severely punished.” Jadó also recommended that authorities require that the alcaldes of each pueblo that participated in the rebellion attend the executions of the main leaders.Footnote 119

Jadó noted repeatedly that the swiftness of González de Prada's army had made all the difference in nipping the uprising in the bud. “If the army had not arrived quickly,” he wrote, “Cajatambo, Conchucos, and even Huayllas [Huaylas] would have joined the insurrection; Huamalíes had already declared itself in.” Pueblos throughout the central Andes had just begun to change sides, believing that “they could now call themselves independent” until “the arrival of the battalions . . . made saints out of everyone.” In Lima, Jadó added, “the revolution has been seen as nothing of consequence,” and that people there believed that “fifty men would have sufficed” to put it down. “How easy it is for the healthy to give advice to the sick and to direct from the shore the movements of a vessel tossed by a hurricane.” In reality, he wrote, “the cancer” of sedition was spreading quickly, and authorities had stopped it not a moment too soon. (Ironically, the metaphor he used to describe the rebellion was the same one that Andean alcaldes had used to describe Spanish abuses; cancer was in the eye of the beholder.) González de Prada's action in Ambo “has not been celebrated,” Jadó concluded, “but it has saved the kingdom.”Footnote 120

Jadó's relief did not last long. In 1814 in Cuzco, creoles led another uprising, this time in defense of the Cádiz Constitution.Footnote 121 As Heraclio Bonilla explains, clergymen also played a leading role. “Bishop José Pérez de Armendáriz actually declared ‘If God places a hand on earthly matters, on the revolution of Cuzco he has placed two.’”Footnote 122 In this rebellion, creole rebels also circulated documents of protest, but for the task of recruiting Andean participants, they appear to have relied less on leaflets and more on the credibility and influence of Mateo Pumacahua, a powerful Andean cacique and erstwhile royalist who had become disillusioned with Spanish authorities. The army he raised helped extend the rebellion into the southern Andes. Yet, as in Huánuco, creoles’ main goal was to secure their own privilege. Ultimately, Bonilla, concludes, “Rebel forces could not reconcile basic differences between whites and Indians, or the rivalries between different groups of Indians.” Abascal's military power was also decisive, but, notably, he relied on many local Andean militias.Footnote 123

The rebellions of Huánuco and Cuzco both reveal the potential and limits of pan-ethnic alliances in late colonial Peru. They also highlight the potential of friars to destabilize colonial structures and spread a vision for a new, independent society. The failure of both rebellions, particularly the failure to form alliances, helps explain Peru's loyalty to Spain into the 1820s. As John Lynch notes, when Simón Bolívar arrived in 1823, he discovered that “Peruvians were indifferent to one cause or the other, that each sector of this highly stratified society sought only to retain its own immediate advantage, that in these circumstances only power could persuade, and only a military victory by an American army could liberate Peru.”Footnote 124

Lack of unity, even against a crumbing Spanish empire, did not augur well for nation-making in the early republican era. Indeed, in the following decades, as Florencia Mallon has written, the new “Peruvian state . . . never stabilized . . . because it repeatedly repressed and marginalized popular political cultures.”Footnote 125 Brooke Larson adds that in the nineteenth century, “liberalism and modernity,” which the Peruvian state largely embraced, “seemed to unleash a new cycle of territorial and cultural conquest” in the Andes.Footnote 126 Throughout the century, Andean communities would have to resist the efforts of state and economic elites who sought to expropriate their lands, commodify their labor, stifle their voices, and erode their culture.Footnote 127 The Huánuco Rebellion of 1812, and especially the friars’ translated pasquinades, remind historians of a brief and often overlooked moment during the first liberal era when ideas of citizenship and common identity seemed at times to portend a slightly different future.