Published online by Cambridge University Press: 01 August 2014

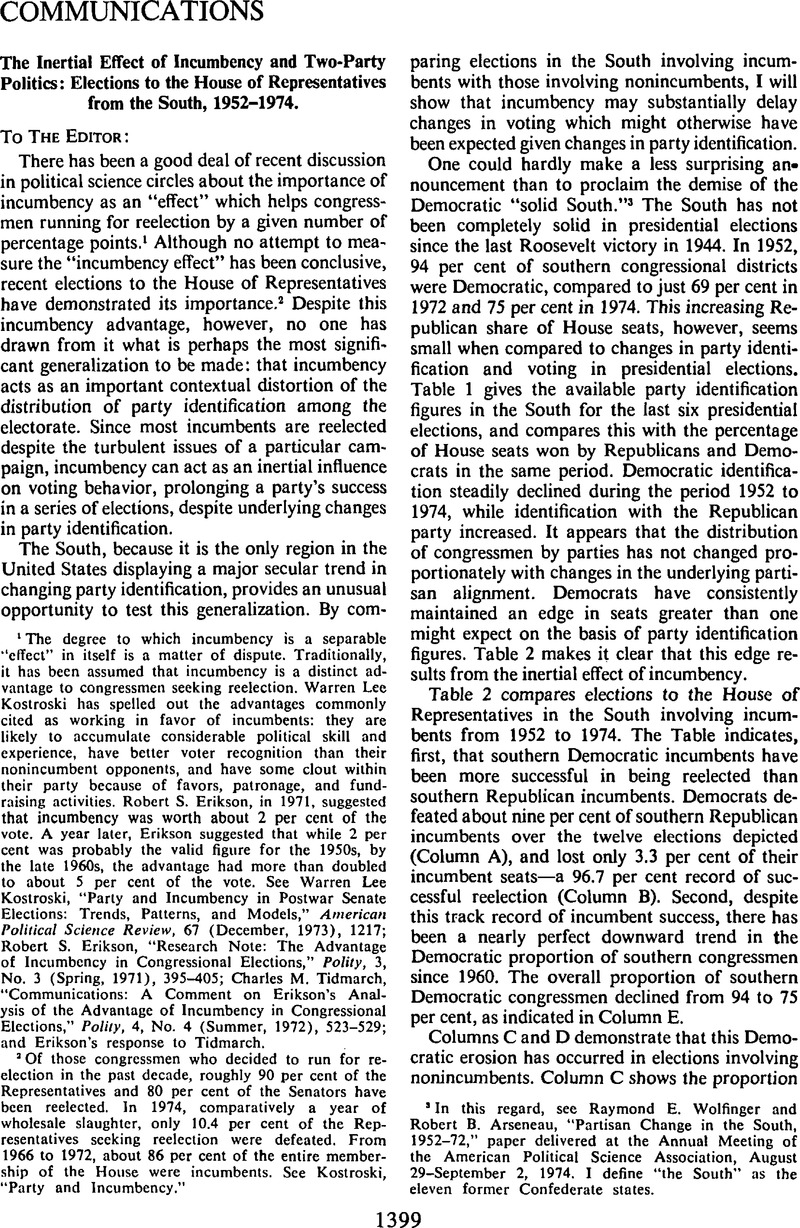

1 The degree to which incumbency is a separable “effect” in itself is a matter of dispute. Traditionally, it has been assumed that incumbency is a distinct advantage to congressmen seeking reelection. Warren Lee Kostroski has spelled out the advantages commonly cited as working in favor of incumbents: they are likely to accumulate considerable political skill and experience, have better voter recognition than their nonincumbent opponents, and have some clout within their party because of favors, patronage, and fundraising activities. Robert S. Erikson, in 1971, suggested that incumbency was worth about 2 per cent of the vote. A year later, Erikson suggested that while 2 per cent was probably the valid figure for the 1950s, by the late 1960s, the advantage had more than doubled to about 5 per cent of the vote. See Kostroski, Warren Lee, “Party and Incumbency in Postwar Senate Elections: Trends, Patterns, and Models,” American Political Science Review, 67 (12, 1973), 1217 CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Erikson, Robert S., “Research Note: The Advantage of Incumbency in Congressional Elections,” Polity, 3, No. 3 (Spring, 1971), 395–405 CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Tidmarch, Charles M., “Communications: A Comment on Erikson's Analysis of the Advantage of Incumbency in Congressional Elections,” Polity, 4, No. 4 (Summer, 1972), 523–529 CrossRefGoogle Scholar; and Erikson's response to Tidmarch.

2 Of those congressmen who decided to run for reelection in the past decade, roughly 90 per cent of the Representatives and 80 per cent of the Senators have been reelected. In 1974, comparatively a year of wholesale slaughter, only 10.4 per cent of the Representatives seeking reelection were defeated. From 1966 to 1972, about 86 per cent of the entire membership of the House were incumbents. See Kostroski, “Party and Incumbency.”

3 In this regard, see Wolfinger, Raymond E. and Arseneau, Robert B., “Partisan Change in the South, 1952–72,” paper delivered at the Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association, 08 29–September 2, 1974 Google Scholar. I define “the South” as the eleven former Confederate states.

4 This indication that incumbency delays changes between parlies suggests the possibility that incumbency may act to delay change within a party as well. Given the “nationalization” of southern politics, the Democratic incumbents are more likely to be “old style” southern Democrats, while the Democratic nonincumbents are more likely to be national Democrats, virtually indistinguishable from their Northern colleagues. Hence, incumbency also may act to delay change within the Democratic party.

5 Wolfinger and Arsenau also document this point strikingly by differentiating “contested” and “uncon tested” elections to the House. See Wolfinger and Arsenau, p. 4.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.