American states, which were once praised by the great jurist Louis Brandeis as “laboratories of democracy,” are in danger of becoming laboratories of authoritarianism as those in power rewrite electoral rules, redraw constituencies, and even rescind voting rights to ensure that they do not lose.

—Levitsky and Ziblatt, How Democracies Die (Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2018, 2)Introduction

The Trump presidency has generated new concerns about authoritarianism and democratic backsliding in the United States (Dionne, Ornstein, and Mann Reference Dionne, Ornstein and Mann2017; Gessen Reference Gessen2016; Lieberman et al. Reference Lieberman, Mettler, Pepinsky, Roberts and Valelly2019). Central to this contemporary discussion has been the measurement of national democratic performance. Prominent cross-national measures of democracy from the Varieties of Democracy Project (V-Dem), Bright Line Watch, and Freedom House, which had once ranked the country as a global leader, show a U.S. democracy slipping toward “mixed regime” or “illiberal democracy” status.

Yet there has been less systematic inquiry into subnational dynamics in American democracy. This is curious in light of American federalism, a comparatively decentralized institutional system that gives state governments the authority to administer elections, draw electoral districts, and exert police power. Louis Brandeis called the states “laboratories of democracy.” But state governments have also been forces against democracy in the US or, in the words of Levitsky and Ziblatt (Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2018, 2), “laboratories of authoritarianism.” State and local governments directly and indirectly enforced a racial hierarchy for most of U.S. history (DuBois Reference DuBois1935; Foner Reference Foner1988). Many scholars do not consider the United States a democracy prior to the national enforcement of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 (VRA) against state governments (King Reference King2017; Mickey Reference Mickey2015)—enforcement made more difficult by the U.S. Supreme Court’s decisions in Shelby County v. Holder (2013) and Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee (2021). Troubling stories abound in recent years, of voter suppression, of gerrymandering, of state legislatures taking power from incoming out-party governors, and of the authoritarian use of police powers against vulnerable communities. But there has been little effort to systematically trace the dynamics of democratic performance in the states during the contemporary period.

In this article, I create a new comprehensive measure of electoral democracy in the U.S. states from 2000 to 2018, the State Democracy Index. Using 51 indicators of electoral democratic quality, such as average polling place wait times, same-day and automatic voter registration policies, and felon disenfranchisement, I use Bayesian modeling to estimate a latent measure of democratic performance. Analysis of the measure suggests that state governments have been leaders in democratic backsliding in the US in recent years.Footnote 1 I find similar trends when using broader measures that cover additional components of democracy such as liberalism and egalitarianism.

I then use the State Democracy Index to investigate the causes of democratic expansion and decline in the states. Prominent theories in political science point to partisan competition (Keyssar Reference Keyssar2000), ideological polarization (Lieberman et al. Reference Lieberman, Mettler, Pepinsky, Roberts and Valelly2019), racial demographic change, and the group interests of national party coalitions (Hacker and Pierson Reference Hacker and Pierson2020) as important drivers of democratic change. Partisan competition can incentivize parties to incorporate new voters (Hajnal and Lee Reference Hajnal and Lee2011; Teele Reference Teele2018b) or generate brinksmanship and scorched-earth tactics (Lee Reference Lee2009). Polarization erodes norms (Levitsky and Ziblatt Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2018) and increases the ideological cost of one’s political opponents taking power (McCarty, Poole, and Rosenthal Reference McCarty, Poole and Rosenthal2006). Status threat stemming from local racial demographic change can provoke institutional backlash against the democratic inclusion of Black and Latino Americans or of recent immigrants (e.g., Bobo and Hutchings Reference Bobo and Hutchings1996; Enos Reference Enos2017). Finally, national parties that represent business have economic incentives to constrain democracy (Ziblatt Reference Ziblatt2017). The contemporary Republican Party is a coalition of the very wealthy, some major industries, and an electoral base motivated in no small part by white identity politics (Parker and Barreto Reference Parker and Barreto2014). These groups have incentives to limit the expansion of the electorate to new voters with very different racial attitudes and class interests, suggesting that Republican control of state government might reduce democratic performance.

I show trends in state democratic performance and test the predictions of these theories with a difference-in-differences design. Across measures and model specifications, the results are remarkably clear: Republican control of state government reduces democratic performance. The magnitude of democratic contraction from Republican control is surprisingly large, about one-half of a standard deviation. Much of this effect is driven by gerrymandering and electoral policy changes following Republican gains in state legislatures and governorships in the 2010 election. Competitive party systems and polarized legislatures do much less to explain the major changes in American democracy in the contemporary period. Moreover, although the Republican Party has capitalized on racial animus in recent elections (Sides, Tesler, and Vavreck Reference Sides, Tesler and Vavreck2018), racial demographic change within states—whether on its own or in conjunction with Republican control—plays little role in state-level democracy. These results point toward national partisan dynamics rather than within-state factors as the driver of democratic change.

As Rocco (Reference Rocco, Lieberman, Mettler and Roberts2021, 6) writes, “[w]hile uneven subnational democracy is preferable to a situation in which territorial governments are evenly undemocratic, the existence of undemocratic outliers nevertheless helps to undermine democracy as a whole.” Just as slavery and Jim Crow in the U.S. South affected the politics and society of the North, democratic backsliding in states like North Carolina and Wisconsin affects other states, and, more importantly, democracy in the United States as a whole. State authorities administer elections, they are the primary enforcers of laws, and they determine in large part who can participate in American politics and how. The policy and judicial landscapes have grown increasingly favorable for policy variation across states in recent years. As a consequence, states may be increasingly important to trends in democracy across all institutions within American federalism. Political scholars, observers, and participants should pay close attention to dynamics in state democracy.

Measuring Democracy in the U.S. States

A rich literature has investigated the behavior of U.S. state governments. One important area of focus has been the relationship between public opinion on the one hand and state legislative votes and policy outcomes on the other (Caughey and Warshaw Reference Caughey and Warshaw2018; Erikson, Wright, and McIver Reference Erikson, Wright and Mclver1993; Flavin and Franko Reference Flavin and Franko2017; Gay Reference Gay2007; Lax and Phillips Reference Lax and Phillips2009; Reference Lax and Phillips2012; Pacheco Reference Pacheco2013; Rogers Reference Rogers2017; Simonovits, Guess, and Nagler Reference Simonovits, Guess and Nagler2019), including whether state governmental responsiveness to the mass public is affected by the influence of concentrated interest groups and wealthy individuals (Anzia Reference Anzia2011; Hertel-Fernandez Reference Hertel-Fernandez2014; Rigby and Wright Reference Rigby and Wright2013). An additional large body of research has asked how state electoral policies affect participation (e.g., Burden et al. Reference Burden, Canon, Mayer and Moynihan2014; Gerber, Huber, and Hill Reference Gerber, Huber and Hill2013). These studies have addressed critical questions of democracy in the states, especially whether state policy outcomes are responsive to and congruent with the policy attitudes of citizens. However, there has been less quantitative study into why state governments expand or restrict democracy—why they make their elections more or less free and fair, and why they exert authority in more or less repressive ways.Footnote 2

There is also a literature on the existence of “authoritarian enclaves” within democratic countries (e.g., Benton Reference Benton2012; Gibson Reference Gibson2013), which are “characterized by an adherence to recognizably authoritarian norms and procedures in contrast to those of the [national] democratic regime” (Gilley Reference Gilley2010, 389). The concept of authoritarian or undemocratic enclaves within partly or fully democratic countries is also seen in historical research on the role of the U.S. states in racially authoritarian and undemocratic governance (King Reference King2017; Kousser Reference Kousser1974; Mickey Reference Mickey2015). Despite such important advances in the comparative and American political development literatures, there is little in the way of systematic quantitative measurement of subnational democratic performance (but see Hill Reference Hill1994).

Conceptualizing Democracy Components

This study follows the conceptual and measurement strategies of comparative cross-national democracy research (e.g., Gleditsch and Ward Reference Gleditsch and Ward1997; Lindberg et al. Reference Lindberg, Coppedge, Gerring and Teorell2014). Conceptualizing democracy to facilitate differentiation, while avoiding “conceptual stretching” (Sartori Reference Sartori1970, 1034), is, of course, challenging. In conceptualizing and operationalizing democracy, I follow scholars in separating the concept into subcomponents. This article focuses mainly on the subcomponent of electoral democracy. Footnote 3 Electoral democracy captures whether a political system has elections that are free, fair, and legitimate, and it is central to historical conceptualization of democracy (Dahl Reference Dahl2003; Schumpeter Reference Schumpeter1942). The antithesis of electoral democracy is autocracy, but I conceptualize electoral democracy as a continuous rather than binary dimension.

An important normative and conceptual basis for electoral democracy can be found in Dahl’s (Reference Dahl1989) discussion of “polyarchy.” The necessary conditions for polyarchy, which Lindberg et al. (Reference Lindberg, Coppedge, Gerring and Teorell2014) use to develop and measure their own cross-national concept of electoral democracy, include elected officials, free and fair elections, inclusive suffrage, the right to run for office, and additional institutional characteristics such as associational autonomy and freedom of expression. Although all of these characteristics are important to this particular study, the most important characteristics that vary across states in the contemporary period are free and fair elections—whether members of the polity have an equal ability to influence electoral (and, by extension, policy) outcomes—and inclusive suffrage—whether members of the polity have equal eligibility and access to the ballot.

Most literature in American politics, including on state politics, argues that correspondence between public opinion and policy outcomes is an important indicator of electoral democracy. Incongruent or unresponsive policy outcomes are signs of a “democratic deficit” (Caughey and Warshaw Reference Caughey and Warshaw2018; Lax and Phillips Reference Lax and Phillips2012). However, I wish to note the tensions of Wollheim’s paradox (Wollheim Reference Wollheim, Blaug and Schwarzmantel2016), in which a legitimate democratic majority supports an undemocratic policy. In such a situation, is it “democratic” to implement an undemocratic policy, such as the disenfranchisement of a minority group, according to the majority will? This paradox is relevant to contemporary policy debates, as surveys find that certain voter suppression policies receive majority support from the American public (e.g., Stewart, Ansolabehere, and Persily Reference Stewart, Ansolabehere and Persily2016). Furthermore, the theoretical tradition of Burkean republicanism proposes a model of representation in which politicians are “trustees” of the public interest who should act on their own beliefs, in contrast to the “delegate” model in which representatives should be responsive to constituent opinion (Miller and Stokes Reference Miller and Stokes1963). In my measures, I attempt to balance both sides of Wollheim’s paradox, considering policy responsiveness to public opinion as well as the cost of voting, partisan bias in districting, and other non-opinion-based dimensions to be important for democratic performance.

As I address in Appendix Section A5, scholars across disciplines (including the V-Dem team) have conceptualized additional important subcomponents of democracy such as liberalism, egalitarianism, deliberation, and inclusion (for examples, see Michener Reference Michener2018; Mills Reference Mills2017; Phillips Reference Phillips1991). I believe that a broader definition of democracy would include these components. I provide two corresponding measurement extensions in the Appendix, where I create and analyze broader measures of democracy in the states. The first extension includes the additional component of liberal democracy. Liberal democracy captures whether a society protects civil rights and liberties (Brettschneider Reference Brettschneider2010; Estlund Reference Estlund2009), especially for minority populations who have been historically subjugated (Glaude Reference Glaude2017; Shelby Reference Shelby2005). Liberal democracy can be contrasted with authoritarianism. An important insight of recent research has been the central role of the carceral state, whether the state represses its citizenry through authoritarian policing and mass incarceration, in shaping democratic performance (Soss and Weaver Reference Soss and Weaver2017). Coercive state authority, seen in extreme forms in authoritarian policing and mass incarceration, are also mostly administered with state-level authority (Miller Reference Miller2008; Soss and Weaver Reference Soss and Weaver2017; Weaver and Prowse Reference Weaver and Prowse2020). Liberal democracy may also include considerations of transparency of decision making and policy information (Shapiro Reference Shapiro2009), and, empirically, democracies are more transparent than are nondemocracies (Hollyer, Rosendorff, and Vreeland Reference Hollyer, Rosendorff and Vreeland2011).

Importantly, liberal democracy is conceptually distinct from “policy liberalism” (Caughey and Warshaw Reference Caughey and Warshaw2016), “size of government” (Garand Reference Garand1988), and other concepts that capture the left–right orientation of policy outcomes across political systems. One might worry that ideological and partisan considerations influence the definition of democracy, which would lead to a tautological study of the causes of democratic changes. However, the main measure in this study, with a focus on electoral democracy, is narrowly defined. In the broader democracy measure used in the Appendix, the indicators of liberal democracy are also circumscribed more narrowly than those often found in comparative democracy research (e.g., Lindberg et al. Reference Lindberg, Coppedge, Gerring and Teorell2014). Furthermore, defining democracy so as to ensure the definition is bipartisan puts democracy research at greater risk of tautology and the “argument from middle ground” fallacy, or, in contemporary parlance, “bothsiderism.”

In a second extension in the Appendix, I create a measure that combines electoral, liberal, and a third component, egalitarian democracy. To varying degrees, scholars have addressed critiques of the concepts of electoral and liberal democracy by emphasizing equality of rights under law—and the realization of rights in practice. These debates helped to conceptualize an egalitarian component of democracy that focuses on material and social equality between individuals and relevant subgroups in the polity (e.g., Brettschneider Reference Brettschneider2010; Przeworski Reference Przeworski1986).

The multitiered federal institutional structure of the US presents an additional conceptual challenge to investigating the democratic performance of states. This idea is related but not identical to what Gibson (Reference Gibson2005, 103) has described as the potential for “an authoritarian province in a nationally democratic country” (see also Gibson Reference Gibson2013). Not only are states not separate, atomized polities from each other horizontally; they are embedded in complex relationships with the federal government vertically in a structure resembling more of a “marble cake” than the “layer cake” of classical dual federalism (Weissert Reference Weissert2011). The particular way the cake is marbled is also in flux, changing dynamically based on the preferences of coalitions (Riker Reference Riker1964; Reference Riker, Greenstein and Polsby1975). More specific to this article’s inquiry into democracy, state governments may act in ways that expand or contract democracy, but only dependent on federal activity. For example, the Supreme Court in Shelby County v. Holder (2013) struck down critical provisions of the Voting Rights Act, allowing states to implement changes to electoral procedures in ways that threaten the freeness and fairness of elections.Footnote 4

Democracy Indicators

I now turn to my democracy indicators, the individual variables that I aggregate into the State Democracy Index measure. For the main State Democracy Index (i.e., electoral democracy) measure, I use 51 indicators. At a level between the indicators and the electoral democracy component, the indicators fit into fmy meso-level categories: gerrymandering (e.g., the partisan efficiency gap), electoral policies that increase or decrease the eligibility to or cost of voting (e.g., felon disenfranchisement laws), electoral policies that increase the integrity of elections (e.g., requiring postelection audits), and observed democratic outcomes (e.g., policy responsiveness to public opinion and wait times for in-person voting). Importantly, the State Democracy Index combines indicators that capture de jure electoral policies and procedures, whereas others measure democratic outcomes like policy responsiveness to public opinion and voting wait times. Together, these indicators capture a large amount of information related to the freedom, fairness, and equality of voice in U.S. elections.

Data on same-day voter registration, early voting, voter ID laws, youth preregistration, and no-fault absentee voting are from Grumbach and Hill (Reference Grumbach and Hill2021), and data on automatic voter registration is from McGhee, Hill, and Romero (Reference McGhee, Hill and Romero2021). Felon disenfranchisement and prisoner voting policies were collected from the National Conference of State Legislatures. Additional electoral variables, especially voting wait times and other indicators of state administrative performance in elections, are from the MIT Election Lab.Footnote 5 Gerrymandering data, which feature prominently in the democracy indices, are provided by Stephanopoulos and Warshaw (Reference Stephanopoulos and Warshaw2020), with an additional district compactness measure from Kaufman, King, and Komisarchik (Reference Kaufman, King and Komisarchik2019).Footnote 6 I also use indicators of policy responsiveness to public opinion (separated into social and economic policy domains) based on the state policy and mass public liberalism measures from (Caughey and Warshaw Reference Caughey and Warshaw2018).Footnote 7 I list all 51 indicators and their sources in Appendix Table A1.

For the alternative measures used in analyses in the Appendix, I use indicators covering liberal democracy and egalitarian democracy. The liberal democracy indicators can be put into three meso-level categories, with a focus on variation in authoritarianism through the carceral state (see Soss and Weaver Reference Soss and Weaver2017): criminal justice policies (e.g., Three Strikes laws), carceral outcomes (e.g., the incarceration rate), and civil liberties policies (e.g., protections for journalists with anonymous sources). Indicators related to criminal justice are from the Correlates of State Policy Database (Jordan and Grossmann Reference Jordan and Grossmann2016) as well as the Bureau of Justice Statistics and Institute for Justice. I also include state asset forfeiture ratings by the Institute for Justice “Policing for Profit” dataset.Footnote 8 Indicators of egalitarian democracy are in five meso-level categories: reproductive rights, rights for racial minorities, rights for sexual minorities, welfare state provisions, and observed socioeconomic equality.

The State Democracy Index covers the years 2000 through 2018. On the one hand, the shortness of this period is a limitation. Variation in electoral democracy across states in the contemporary period, which is the focus of this article, is much smaller than variation during the slavery and Jim Crow periods. However, through voter registration rules, election administration procedures, and laws that unequally increase the cost of voting, states still vary considerably in how inclusive suffrage is. States’ gerrymandering of legislative district boundaries has also generated variation in how free and fair elections are, expanding inequality in how much individuals’ votes influence election outcomes and reducing the potential for majoritarian rule. Furthermore, there are serious challenges to creating a measure that directly compares interstate variation in democracy in the contemporary period with that of earlier eras, such as the Jim Crow period.Footnote 9 By limiting the State Democracy Index to the past two decades, I both capture an era of important contestation over American democracy and avoid bridging between periods for which there is very different data availability, and, more importantly, potentially incomparable terms of civil and human rights.

Measurement Models

For the main State Democracy Index measure, I model democracy as a latent variable (Treier and Jackman Reference Treier and Jackman2008). This latent variable analysis lets observed relationships between the democracy indicators determine how each indicator should affect states’ democracy scores. This strategy estimates an “ideal point” on a latent dimension for each state-year that best predicts the values of democracy indicators in the observed data. In particular, I use Bayesian factor analysis for mixed data (Quinn Reference Quinn2004) because the democracy indicators may be binary (e.g., same-day voter registration), ordinal (e.g., disenfranchisement of all, some, or no felons), or continuous (e.g., legislative district efficiency gap). The model is based on the equation below. The distribution of democratic performance on indicators for state

![]() $ s $

in year

$ s $

in year

![]() $ t $

,

$ t $

,

![]() $ {y}_{st}^{\ast } $

, is a function of the state’s latent democratic performance for that year,

$ {y}_{st}^{\ast } $

, is a function of the state’s latent democratic performance for that year,

![]() $ {\theta}_{st} $

, as well as the democracy indicator’s discrimination parameter

$ {\theta}_{st} $

, as well as the democracy indicator’s discrimination parameter

![]() $ {\beta}_j $

and difficulty parameter

$ {\beta}_j $

and difficulty parameter

![]() $ {\alpha}_j $

.Footnote 10 Subscript

$ {\alpha}_j $

.Footnote 10 Subscript

![]() $ j $

denotes different indicators, which are analogous to test questions in the item response theory framework. In this equation,

$ j $

denotes different indicators, which are analogous to test questions in the item response theory framework. In this equation,

![]() $ {N}_j $

is a normal distribution with

$ {N}_j $

is a normal distribution with

![]() $ j $

dimensions (as there are

$ j $

dimensions (as there are

![]() $ j $

indicators) and

$ j $

indicators) and

![]() $ \Psi $

is a

$ \Psi $

is a

![]() $ J\times J $

variance-covariance matrix.

$ J\times J $

variance-covariance matrix.

The main benefit of this factor analysis is that the measure requires little in the way of assumptions from us about how any particular indicator should affect democracy scores.Footnote 11 However, this comes at the cost of some loss of control; in some circumstances, the estimated parameters for democracy indicators can be “wrong” in theoretical and substantive terms. Whether or not you consider this a serious problem is dependent on whether you philosophically interpret these “errors” as measurement error or bias.Footnote 12 In addition, the Bayesian factor analysis model provides estimates of uncertainty for parameters (both state democracy scores and democracy indicator item parameters).

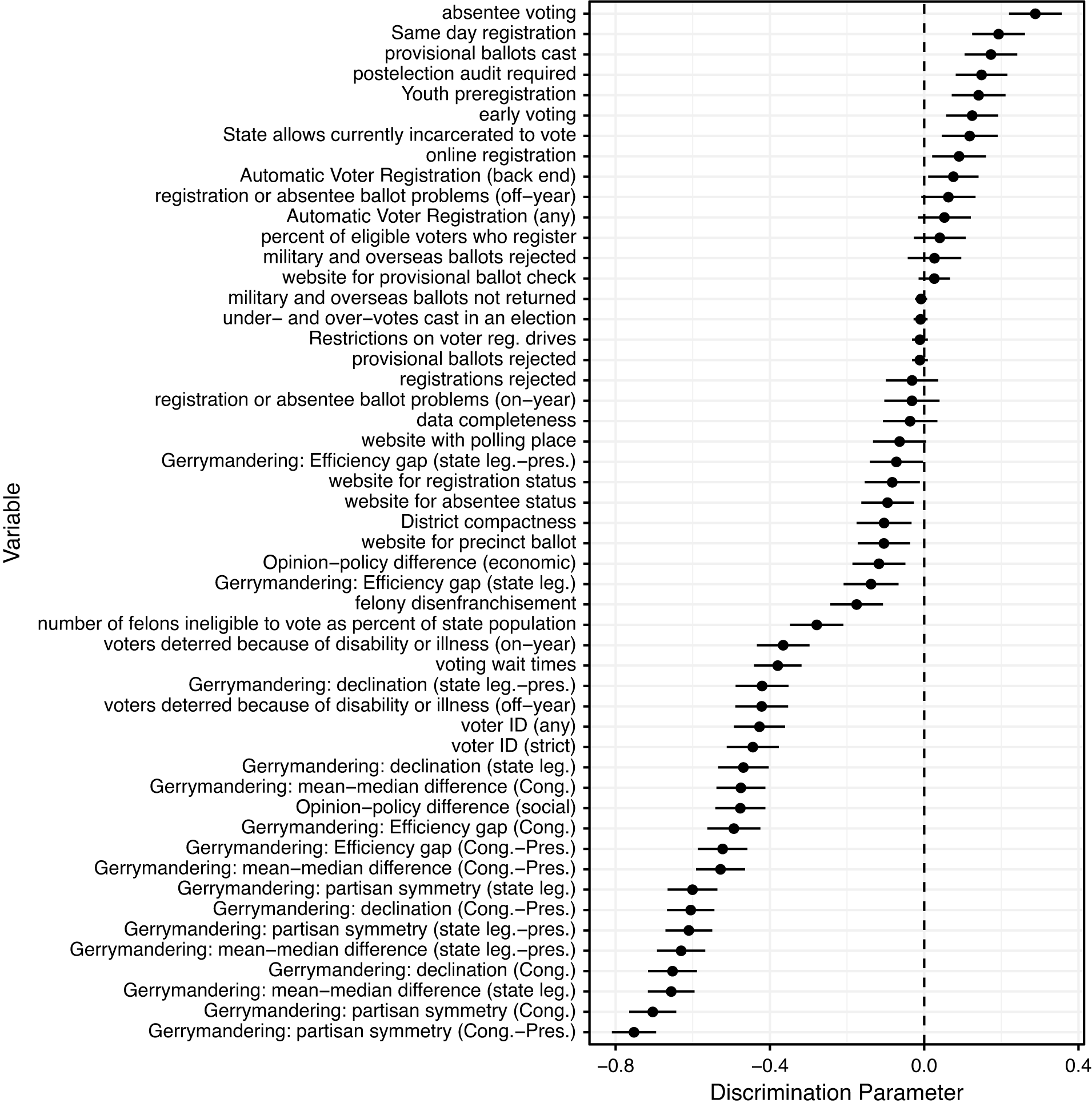

Figure 1 shows the discrimination parameter estimates,

![]() $ {\beta}_j $

for democracy indicator

$ {\beta}_j $

for democracy indicator

![]() $ j. $

In short, the discrimination parameters represent the slope of the relationship between an indicator and a state’s latent democracy performance score. Indicators with positive discrimination parameters increase a state’s democracy score, whereas items with negative parameters decrease them.Footnote 13 The discrimination parameters in Figure 1 suggest that a small number of indicators do not load well onto the latent democracy dimension (with discrimination parameters close to zero), such as the number of military and overseas ballots not returned and restrictions on voter registration drives. Overall, however, the item discrimination parameters are consistent with theoretical expectations and suggest that electoral democracy is unidimensional.

$ j. $

In short, the discrimination parameters represent the slope of the relationship between an indicator and a state’s latent democracy performance score. Indicators with positive discrimination parameters increase a state’s democracy score, whereas items with negative parameters decrease them.Footnote 13 The discrimination parameters in Figure 1 suggest that a small number of indicators do not load well onto the latent democracy dimension (with discrimination parameters close to zero), such as the number of military and overseas ballots not returned and restrictions on voter registration drives. Overall, however, the item discrimination parameters are consistent with theoretical expectations and suggest that electoral democracy is unidimensional.

Figure 1. Factor Loadings of Democracy Indicators

Note: The figure presents the discrimination parameter estimates and Bayesian credible intervals for indicators used in the State Democracy Index.

When item parameters do not conform to theory, one solution is to directly impose item parameters on the indicators rather than model them. To do so, in addition to the Bayesian factor analysis measure, I use simple additive indexing to create an alternative democracy measure. In the additive index, I weight each democracy indicator equally by range, scaling each to the [0,1] interval, and then take the state average across all the indicators. Policies that are democracy contracting, such as felony disenfranchisement, are reverse coded. This is equivalent to adding up all of a state’s democracy-expanding policies and then subtracting the sum of democracy-contracting policies (for applications of this method to state policy liberalism, see Erikson, Wright, and McIver Reference Erikson, Wright and Mclver1993; Grumbach Reference Grumbach2018). I provide robustness checks with this additive measure in the Appendix, and the results are very similar to the results with the data-driven Bayesian measure used in the main analyses.

I test the validity of the State Democracy Index in different ways. I check construct validation by comparing my measure to measures of related concepts. To my knowledge, the closest analogue to my measure is the Cost of Voting Index (COVI) from Li, Pomante, and Schraufnagel (Reference Li, Pomante and Schraufnagel2018), which is based on seven state electoral policy variables in presidential election years. State democracy, as a concept, is related to the cost of voting. I therefore check my measure’s convergent validity by estimating its correlation to this previous measure in Figure A1 in the Appendix, finding a moderately strong correlation of -0.71 (higher values of COVI indicate greater cost of voting). I also show that my measure is positively correlated with state-level turnout of the voting-eligible public in Figure A2 in the Appendix. I unfortunately have little opportunity to test for convergent validation because of the lack of existing measures of overall state-level democratic performance. There is scholarly interest in measuring subnational democratic performance at the country level (see Giraudy Reference Giraudy2015; McMann Reference McMann2018), and a small number of quantitative measures of democracy within other countries’ political subunits (Harbers, Bartman, and van Wingerden Reference Harbers, Bartman and van Wingerden2019), but I have not found such a measure of democratic performance focused on the U.S. states.

In the next sections, I investigate descriptive trends in state democratic performance and then turn to explaining these trends with theories based in party competition, polarization, demographic change, and the group interests of national party coalitions.

Trends in State Democracy

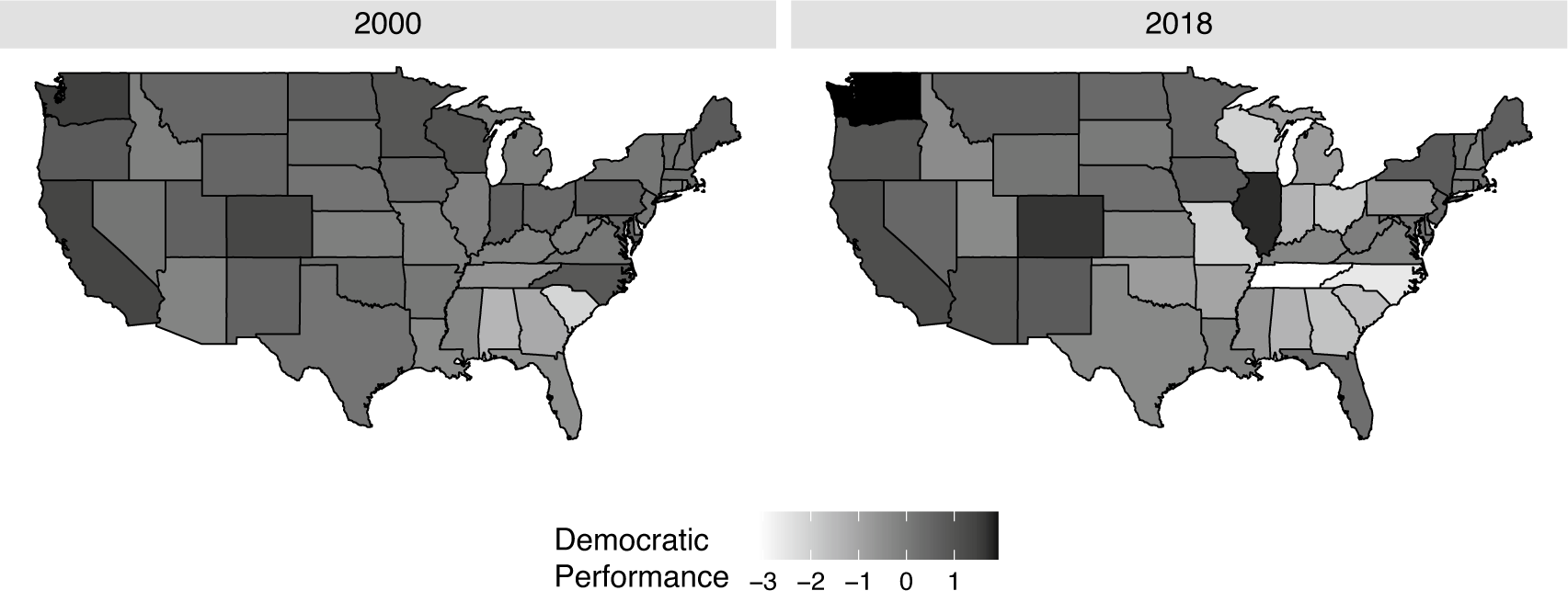

With the State Democracy Index in hand, I first explore variation between states, and within states across time, in democratic performance. Figure 2 shows a map of state scores in the year 2000 (left panel) and in the year 2018 (right panel).

Figure 2. Democracy in the States, 2000 and 2018

Note: Left panel shows State Democracy Index scores for the year 2000. Right panel shows State Democracy Index scores for the year 2018.

The maps in Figure 2 show some clear regional variation, especially in 2018. States on the West Coast and in the Northeast score higher on the democracy measures than do states in the South. New Mexico, Colorado, and some Midwestern states also have strong democracy scores.

The maps also show within-state change during this period. States like North Carolina and Wisconsin are among the most democratic states in the year 2000, but by 2018 they are close to the bottom. Illinois and Vermont move from the middle of the pack in 2000 to among the top democratic performers in 2018.

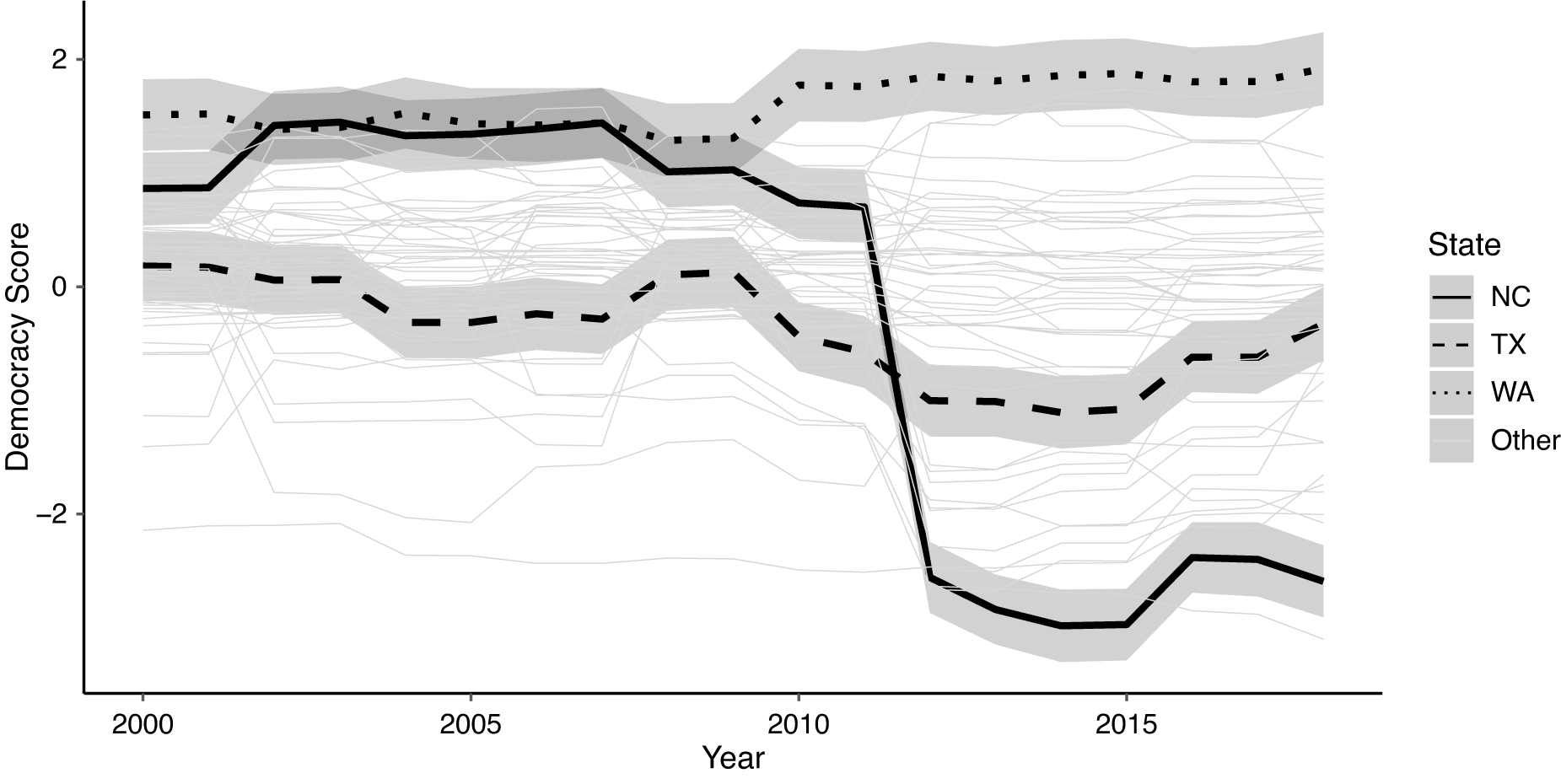

Figure 3 highlights a case of major change in democratic performance, North Carolina. Although the state was notoriously difficult to democratize during the civil rights period (Mickey Reference Mickey2015)—it maintained its Jim Crow literacy tests for voting until the 1970s—North Carolina had become a leader in expanding access to voting during the late 1990s and early 2000s. The state had expanded opportunities for early voting as well as implemented policies to expand voter registration, such as same-day registration and preregistration for youth. Voter turnout had increased by over 10 percentage points on average during this time.

Figure 3. The Weakening of Democracy in North Carolina

Note: Lines represent the State Democracy Index scores for states (2000–2018). The solid black line represents North Carolina, the dashed line represents Texas, and the dotted line Washington. Shaded ribbons are Bayesian credible intervals.

But a major shift occurred after the Republican Party won control of both legislative chambers in 2010. Beginning in 2011, North Carolina made a series of changes to its election laws and procedures. The state redrew its legislative district boundaries. The new districts, which received rapid condemnation from Democrats and civil rights groups, clearly advantaged white and Republican voters. In 2018, for example, Republicans won about 50.3% of the two-party vote in North Carolina—but this bare majority of votes from the electorate translated to fully 77% (10 of 13) of North Carolina’s seats in Congress. Scholars of gerrymandering such as Christopher Warshaw have called North Carolina districts “probably the most gerrymandered map in modern history.”Footnote 14 After electing a Republican governor in 2012, the unified Republican government then implemented a strict voter ID law and curtailed early voting laws in areas with heavier concentrations of Black voters. These changes are reflected in Figure 3.

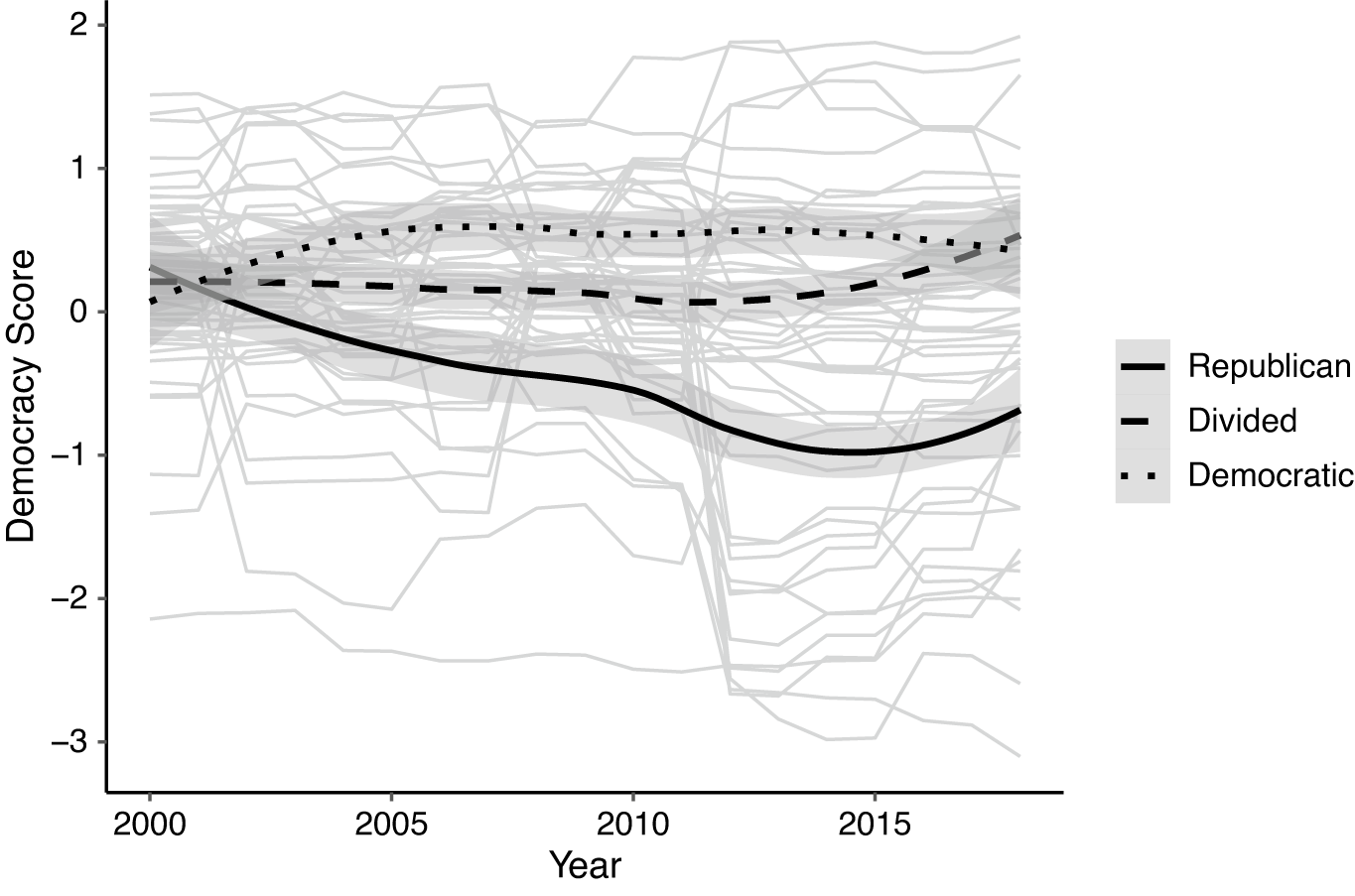

Figure 4 shows trends in state democracy by party, with the solid line representing unified Republican states and the dashed and dotted lines representing Democratic and divided states, respectively. The states polarize by party over this period: the average divided state and Democratically controlled state become more democratic, whereas the average Republican-controlled state becomes less democratic. However, the groups of states controlled by each party change over this period; I do not know from Figure 4 whether Republican states are becoming less democratic or whether less democratic states are becoming more Republican. The partisan relationships could also be confounded by other potential causes of democratic changes: competition and polarization.

Figure 4. Democracy in the States by Party Control of Government

Note: Plot shows average State Democracy Index scores for states under unified Democratic (dotted line), divided (dashed line), and unified Republican (solid line) control. Shaded ribbons are 95% confidence intervals.

Explaining Dynamics in State Democracy

The State Democracy Index measures developed in the previous sections suggest that there have been major shifts in democratic performance within states in recent years. However, the important question is not simply how democracy has changed in the states but why. Luckily, the new democracy measures allow us to test the predictions of competing theories of the causes of democratic changes.

What drives democratic expansions and contractions in political systems? Political science offers some potential explanations. The explanations engage with transformative processes in modern American politics: partisan competition, ideological polarization, and national party group coalitions. Scholars point to the consolidation of a competitive party system to explain large-scale expansions of democracy in the US (Teele Reference Teele2018a), Africa (Rakner and Van de Walle Reference Rakner and Van de Walle2009), Europe (Mares Reference Mares2015), and around the world (Weiner Reference Weiner1965). Parties in competitive environments might have incentives to expand the electorate in search of more votes, improving democracy in the process by, for example, expanding the franchise (Keyssar Reference Keyssar2000; Teele Reference Teele2018b). On the other hand, however, by incentivizing partisan brinksmanship (Lee Reference Lee2009), partisan competition can lead a party with a precarious grip on power to diminish democracy by exploiting countermajoritarian institutions and attempting to prevent their opponents’ electoral bases from voting. I follow research that uses measures of legislative and electoral competition within states as primary explanatory variables (O’Brian Reference O’Brian2019; Teele Reference Teele2018b).

A second theory focuses on polarization—the ideological distance between the parties’ agendas. Polarization increases politicians’ need to ensure that their opponents do not win office. A party in government in a polarized state will thus have greater incentive to change policies that affect democracy, such as election laws that influence the cost of voting for different groups in the state. As Lieberman et al. (Reference Lieberman, Mettler, Pepinsky, Roberts and Valelly2019, 471) argue, “hyperpolarization magnifies tendencies for the partisan capture of institutions that are supposed to exercise checks and balances but may instead be turned into unaccountable instruments of partisan or incumbent advantage.” It “erodes norms” of institutional behavior, such as the judicious use of executive power and fair treatment on issues such as bureaucratic and judicial appointments—and the levers of democracy, itself (Levitsky and Ziblatt Reference Levitsky and Ziblatt2018). Polarization may be asymmetric or symmetric (Hacker and Pierson Reference Hacker and Pierson2005; McCarty, Poole, and Rosenthal Reference McCarty, Poole and Rosenthal2006), but polarization is fundamentally about the distance between the parties. I follow literature that uses the difference in party medians in state legislatures as a measure (Shor and McCarty Reference Shor and McCarty2011).

A third theoretical tradition suggests that the racial demographics of state populations shapes politics and policy (Hero and Tolbert Reference Hero and Tolbert1996). Of particular importance to this study is the potential for increasing racial diversity to generate “racial threat” and backlash among conservative white voters (Bobo and Hutchings Reference Bobo and Hutchings1996). As states grow more racially diverse due to immigration and internal migration,Footnote 15 some voters might demand restrictions on democracy to block the political inclusion and empowerment of new voters of color (Abrajano and Hajnal Reference Abrajano and Hajnal2017; Biggers and Hanmer Reference Biggers and Hanmer2017; Myers and Levy Reference Myers and Levy2018). Importantly, racial backlash would not only lead to democratic backsliding on its own; if demographic change leads voters to increasingly elect Republicans to state government, this theory predicts that the interaction of demographic change and Republican Party control should produce democratic backsliding.

Finally, a set of theories focuses not on competition, polarization, or demographic change within states but on the interests of groups in national party coalitions. Tor instance, Ziblatt (Reference Ziblatt2017) points to the importance of conservative parties as historical coalitions of groups with economic incentives to constrain democracy. The modern Republican Party, which, at its elite level, is a coalition of the very wealthy, has incentives to limit the expansion of the electorate with new voters with very different class interests (Hacker and Pierson Reference Hacker and Pierson2020). In recent years, large firms and wealthy individuals have made major political investments at the state level, providing “legislative subsidies” in the form of model bills, lobbying, and organization, as Hertel-Fernandez (Reference Hertel-Fernandez2019) shows in the cases of the American Legislative Exchange Council, Americans for Prosperity, and the State Policy Network.

In contrast, the GOP’s electoral base is considerably less interested in the Republican economic agenda of top-heavy tax cuts and reductions in government spending. However, their preferences with respect to race and partisan identity provide the Republican electoral base with reason to oppose democracy in a diversifying country. (Survey evidence from Graham and Svolik (Reference Graham and Svolik2020) also suggests that American voters have little interest in maintaining democratic performance if it means conceding their partisan or policy goals.) The politics of race are therefore still central to this theory of party coalitions. However, unlike the localized racial and political economy conflict of the Jim Crow period, today it is national rather than state or local level racial conflict that is the driver.

Furthermore, increasing economic inequality since the 1970s has caused the economic interests of those at the top to diverge from those of the median voter (Meltzer and Richard Reference Meltzer and Richard1981). This divergence incentivizes economic elites to either moderate their economic agenda—which the Republican Party has not done—or to appeal to alternative dimensions of political conflict (Hacker and Pierson Reference Hacker and Pierson2020), the most contentious of which in the US is race but can also include conflict over gender, religion, sexuality, and culture. Overall, this theory suggests that the current coalitional structure of the national Republican Party, shaped in large part by twentieth-century racial realignment (Schickler Reference Schickler2016) and large political investments by wealthy individuals and firms (Hacker and Pierson Reference Hacker and Pierson2010; Hertel-Fernandez Reference Hertel-Fernandez2019), makes the party in government especially likely to reduce state democratic performance in any state in which it takes power.

I am also interested in the interactions of competition, polarization, and Republican control. Polarization might only matter in competitive contexts, when the ideologically distant out-party has a real chance of taking power. Similarly, Republican control might only lead to backsliding in a competitive environment where they risk losing legislative majorities and governorships. The interaction of polarization and Republican control might produce backsliding if backsliding is being driven by the most ideologically extreme Republican state legislatures. Furthermore, the interaction of racial demographic change and Republican control might lead to backsliding if growing minority populations provoke racial threat among white voters, leading them to elect Republicans, with a goal of stemming the expanding electoral power of minority voters.

I continue this discussion of the potential causes of democratic expansion and contraction in Appendix Section A7. The next section describes the data collection and empirical strategy for testing these theories of democracy in the states.

Empirically Testing Theories of Democracy

To empirically test these theories, I collect time-series measures of political competitiveness, polarization, party control, and demographic change. I use data on legislative seat shares from Klarner (Reference Klarner2013) to measure legislative competitiveness. Specifically, I calculate states’ lower legislative chamber competitiveness as

![]() $ -\mid 0.5-{D}_{lower}\mid $

, where

$ -\mid 0.5-{D}_{lower}\mid $

, where

![]() $ {D}_{lower} $

is the two-party share of lower chamber seats held by Democrats, and upper chamber competitiveness as

$ {D}_{lower} $

is the two-party share of lower chamber seats held by Democrats, and upper chamber competitiveness as

![]() $ -\mid 0.5-{D}_{upper}\mid $

, where

$ -\mid 0.5-{D}_{upper}\mid $

, where

![]() $ {D}_{upper} $

is the two-party share of upper chamber seats held by Democrats.Footnote 16 In robustness checks in the Appendix, I use an additional measure of electoral rather than legislative competitiveness from O’Brian (Reference O’Brian2019), which I code as

$ {D}_{upper} $

is the two-party share of upper chamber seats held by Democrats.Footnote 16 In robustness checks in the Appendix, I use an additional measure of electoral rather than legislative competitiveness from O’Brian (Reference O’Brian2019), which I code as

![]() $ -\mid 0.5-{D}_{votes}\mid $

, where

$ -\mid 0.5-{D}_{votes}\mid $

, where

![]() $ {D}_{votes} $

is the two-party share of votes in the state’s U.S. House election(s) that went to Democratic candidates.Footnote 17 As is customary, these measures are smoothed into rolling averages across three election cycles (e.g., Ranney Reference Ranney, Jacob and Vines1976; Shufeldt and Flavin Reference Shufeldt and Flavin2012), but I lag them in statistical models such that they capture electoral competition in the three previous election cycles prior to the state’s democratic performance in year

$ {D}_{votes} $

is the two-party share of votes in the state’s U.S. House election(s) that went to Democratic candidates.Footnote 17 As is customary, these measures are smoothed into rolling averages across three election cycles (e.g., Ranney Reference Ranney, Jacob and Vines1976; Shufeldt and Flavin Reference Shufeldt and Flavin2012), but I lag them in statistical models such that they capture electoral competition in the three previous election cycles prior to the state’s democratic performance in year

![]() $ t $

.

$ t $

.

Legislative polarization measures are from Shor and McCarty (Reference Shor and McCarty2011). I use the average distance in the parties’ legislative chamber medians within each state.Footnote 18 Measures of competitiveness and polarization are standardized to have a mean of 0 and a standard deviation 1 for clarity. Republican control is a binary variable that takes a value of 1 if the state is under unified Republican control and 0 if the state is under Democratic or divided control.Footnote 19 State racial demographics are from the U.S. Census Bureau’s “bridged” 1990–2019 state race population estimates.Footnote 20 I measure demographic change in four-year rolling averages, but the results are robust to the use of different year increments. State party control data are from Klarner (Reference Klarner2013), which I extend through 2018 using National Conference of State Legislatures data.Footnote 21 I exclude Nebraska from the analyses due to its nonpartisan unicameral legislature.

I test theoretical predictions with a difference-in-differences design that exploits within-state variation. Although the true causal model between competition, polarization, demographic change, party control, and democratic performance is likely to involve a structure of highly complex feedback relationships, this design eliminates time-invariant differences between states—the main potential source of bias in estimating the relationship between my input measures and democratic performance.Footnote 22 I supplement traditional two-way fixed effects models with a generalized synthetic control estimator from (Xu Reference Xu2017) and alternative methods of aggregating treatment effects from Callaway and Sant’Anna (Reference Callaway and Pedro2020) that avoid potential weighting problems in multiperiod difference-in-differences designs.

Results

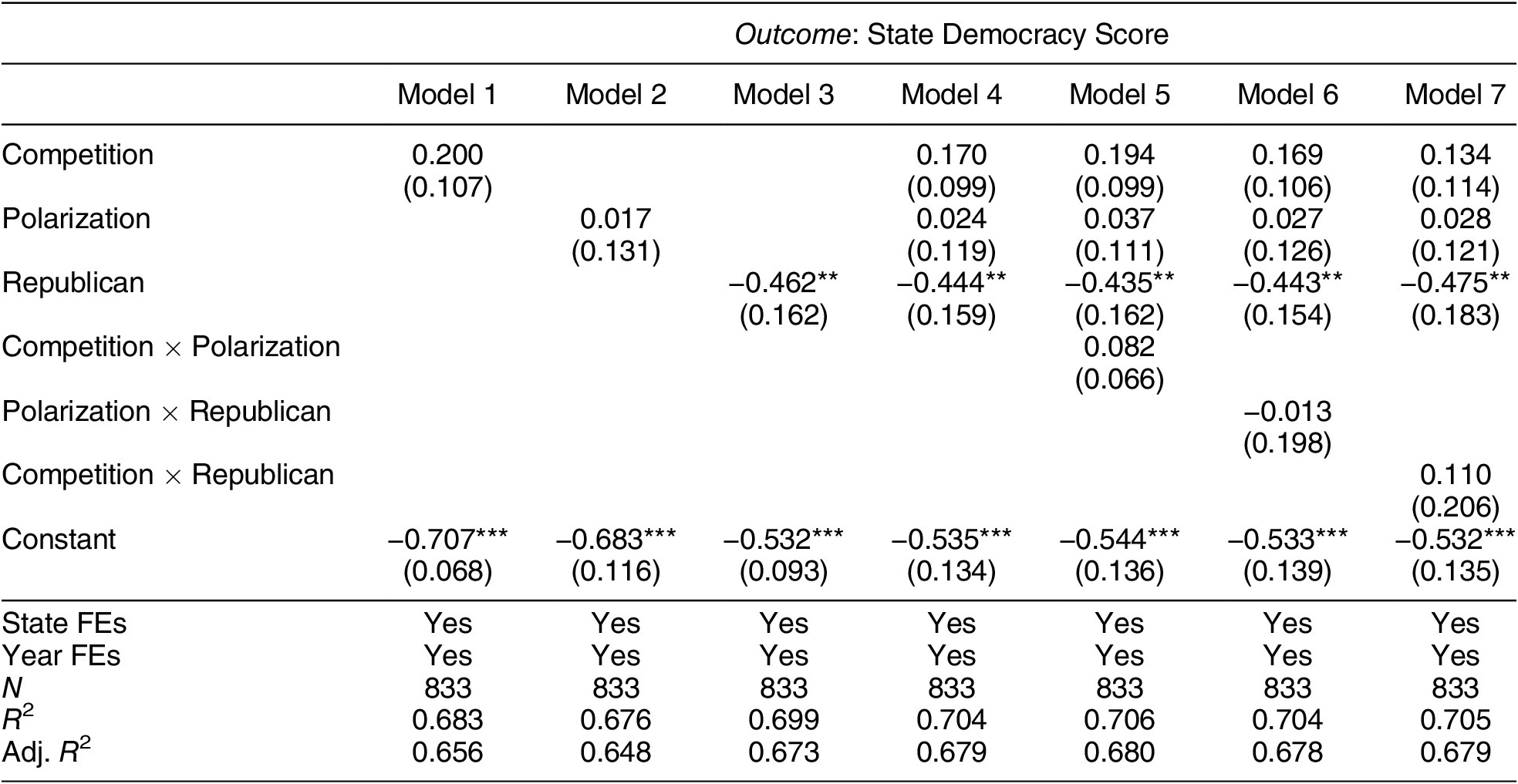

I present the main results in Table 1. The results of Models 1 through 3 show that, on their own, there is a modest and sometimes statistically significant positive relationship between competition and democracy and no relationship between polarization and democracy—but there is a large negative relationship between Republican control and democracy in the states. Across the model specifications, the estimates of the effect of Republican control of government are between 0.442 and 0.481 standard deviations of democratic performance, a substantial amount. The effect of competition, in contrast, is between 0.141 and 0.206 standard deviations, and the effect of polarization is very small and in the unexpectedly positive direction.

Table 1. Explaining Dynamics in State-Level Democracy

Note: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

I am also interested in the interactions of competition, polarization, and Republican control. Polarized parties (or the Republican Party) might only have an incentive to restrict democracy in competitive political environments. However, the results in Table 1 suggest that these interactions do little to explain dynamics in state democracy. The interaction of competition and polarization is modestly positive, as is the interaction of competition and Republican control—both contrary to expectations (though all of the interaction coefficients are statistically insignificant).

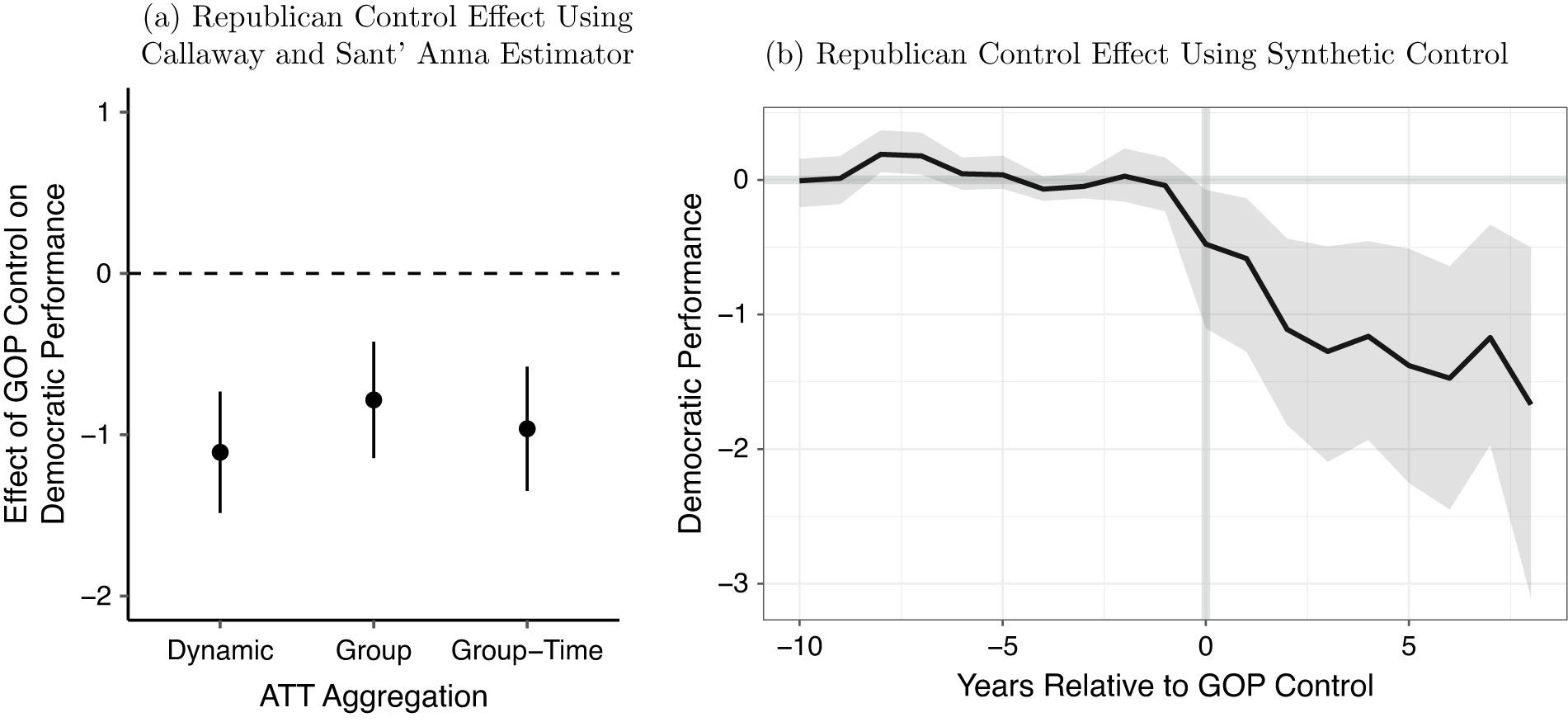

Due to recent concern about the weighting of treatment estimates in multiperiod difference-in-differences analysis using two-way fixed effects (Goodman-Bacon Reference Goodman-Bacon2018), I use alternative aggregation procedures to estimate the average treatment effect on the treated (ATT) of Republican control.Footnote 23 In Panel (a) of Figure 5, I plot the results from three different types of ATT aggregation from Callaway and Sant’Anna (Reference Callaway and Pedro2020): dynamic, group, and simple (group-time). In addition to using different aggregation procedures, the model drops states that were “treated” (i.e., under Republican control) in the first period, the year 2000.Footnote 24 In Panel (b), I plot the effects of GOP control using the generalized synthetic control (GSC) method from Xu (Reference Xu2017). The GSC technique relaxes the parallel trends assumption in the difference-in-differences designs used throughout this article by creating synthetic control units that are weighted averages of the “real” control units, each constructed to closely match the pretreatment democratic performance in states that will eventually be treated by GOP control (for other examples of GSC in political science, see Gilens, Patterson, and Haines Reference Gilens, Patterson and Haines2021; Marble et al. Reference Marble, Mousa, Siegel and Alrababa’h2021).

Figure 5. Effect of Republican Control on Democratic Performance

Note: Panel (a) shows results using the Callaway and Sant’Anna estimator alternative ATT aggregation methods. Panel (b) shows the results of a generalized synthetic control analysis.

Compared with the main state and year fixed effects results in Table 1, the results in Figure 5 show an even larger effect of Republican control. The results in Panel (a) using the Callaway and Sant’Anna (Reference Callaway and Pedro2020) estimators increase my confidence that the Republican control findings are not being driven by the particular timing of treatment (i.e., change in party control) and the time heterogeneity of treatment effects, whereas the GSC estimates in panel (b) increase my confidence that the effect is robust to equalizing pretrends in democratic performance.Footnote 25

In the Appendix, I show that these results are robust under a wide variety of conditions. First, I replicate these results using the additive democracy index described earlier in which each democracy indicator is weighted equally. The results in Appendix Table A2 are substantively unchanged. Second, I replicate the main analyses using a measure of partisan electoral competitiveness (i.e., the closeness of elections) rather than legislative competitiveness (i.e, the narrowness of partisan legislative majorities). Table A3 in the Appendix shows results consistent with the main results, but with one important difference. Although the effects of competitiveness, polarization, and Republican control remain very similar to the main results, the interaction of competitiveness and Republican control is negative, significant, and relatively substantial in magnitude (-0.262 standard deviations of State Democracy Index scores). Among Republican-controlled states, in other words, those whose recent elections have been especially competitive are the states that take steps to reduce their democratic performance.Footnote 26

In Appendix Section A6, I replicate the main analyses with alternative measures of democracy. The first measure covers liberal and electoral democracy (using 61 total indicators), and the second covers liberal, electoral, and egalitarian democracy (using 116 total indicators). The additional liberal democracy indicators extend the measure’s coverage to issues of civil liberties and freedom from state authority in areas such as policing, incarceration, and freedom of the press. The egalitarian democracy indicators include measures of economic inequality, women’s rights, campaign finance policy, labor rights, and LGBT rights, which scholars have argued are integral to the realization of democracy in practice. The results from the additional analyses are substantively very similar to the analyses using the main (electoral) State Democracy Index measure, with Republican control significantly reducing democratic performance, and little explanatory role for other potential causes of democratic change.

Racial Demographic Change and State Democracy

In this section, I turn to the analysis of racial demographic change and its interaction with competition, polarization, and Republican governance. I first assess descriptive trends. Figure 6 plots Black and Latino population change in the five states that experience the greatest democratic backsliding over the period: Alabama, Ohio, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Wisconsin. These states tend to have above-average Black population shares, but they see little change over time. In contrast, these states have relatively low Latino population shares. Their Latino populations grow gradually over this period. However, this amount of growth is not out of the ordinary; the trends in these states closely track national averages. This descriptive analysis provides little evidence that local Black or Latino population change matters much for state democratic performance.

Figure 6. Black and Latino Population Change in the States

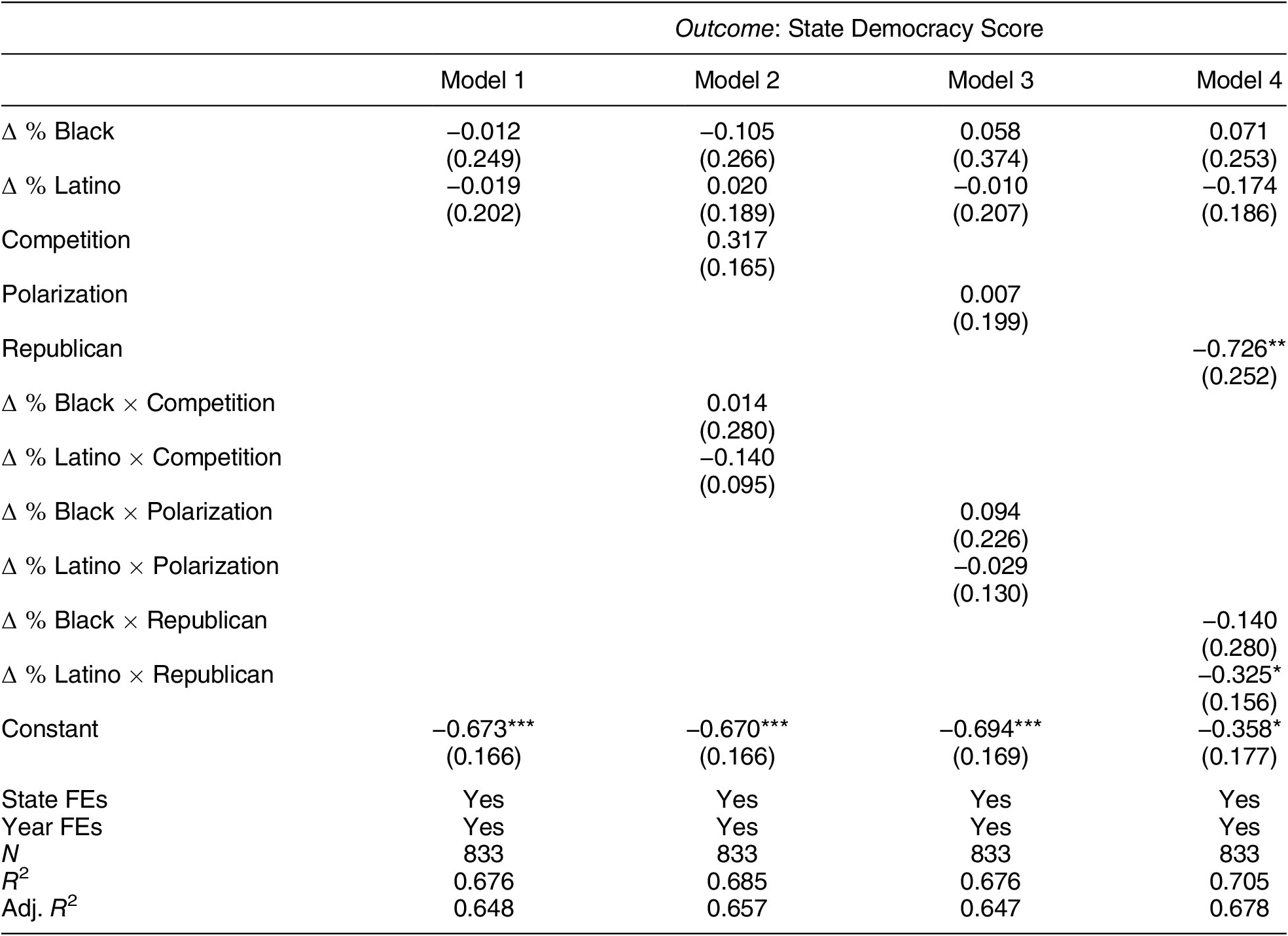

Table 2 tests theories of demographic threat with the main difference-in-differences design. The results are consistent with the descriptive analysis: trends in racial population proportions have little effect on state democratic performance. Furthermore, although Republican control still has a large negative effect on democratic performance, the interaction of Republican control and demographic change generally matters little. Unexpectedly, the one statistically significant coefficient involving demographic change is the positive coefficient for the interaction of Republican control and Latino population change, meaning that Republican states with greater Latino population growth reduce democratic performance slightly less than do other Republican states (though with a coefficient of 0.325 corresponding to a 1 percentage-point increase in state percentage Latino, or nearly two standard deviations, this effect is small in substantive magnitude).Footnote 27

Table 2. Racial Demographic Change and State Democracy

Note: *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

These findings suggest that racial politics within states are not central to dynamics in state democracy.Footnote 28 This does not mean that race is peripheral to dynamics in state democracy. On the contrary, they are consistent with a central role of race in national political conflict, especially at the mass level (Parker and Barreto Reference Parker and Barreto2014; Sides, Tesler, and Vavreck Reference Sides, Tesler and Vavreck2018). A number of important studies show evidence of racial threat and contestation at highly localized levels (e.g., Enos Reference Enos2017). But in an era of highly nationalized American politics (Hopkins Reference Hopkins2018), when it comes to state governmental choices over democratic institutions, the critical question is not about racial politics within a state but whether the state government is part of the national Republican Party.

Therefore, these findings, suggest a contrast from the racial politics of Jim Crow. Although contemporary state electoral legislation, like that of the Jim Crow era, has been found by courts to have been “motivated at least in part by an unconstitutional intent to target African American voters,”Footnote 29 battles over voting rights from the 1890s through 1970s primarily involved battles between large landowners, Black activists, and other “indigenous” pro- and antidemocracy interest in Southern states (Mickey Reference Mickey2015). In such a political economy, states’ racial demographics play a central role in explaining variation in subnational democratization. In contrast, the results in this article emphasize the importance of national political forces.

Conclusion

Despite the national focus of much contemporary discourse about democratic backsliding in the US and abroad, state governments have constitutional authority to structure and administer many of the most important democratic institutions in the American political system. This article creates a new measure of electoral democracy in the 50 states from 2000 to 2018, based on 51 indicators. In the Appendix, I construct additional measures that also cover liberal democracy and egalitarian democracy.

The measure, the State Democracy Index, suggests that there have been dramatic shifts in democratic performance in the American states over this period. In some states, democracy expanded in inclusive ways, expanding access to political participation, reducing the authoritarian use of police powers, and making electoral institutions more fair. In other states, however, democracy narrowed dramatically, as state governments gerrymandered districts and created new barriers to participation and restrictions on the franchise.

My measure opens up new opportunities for research on questions related to representation and democracy, as well as federalism and state and local politics. Scholars might be interested in investigating the role of interest groups or money in politics on state democratic performance (Anzia and Moe Reference Anzia and Moe2017; Hertel-Fernandez Reference Hertel-Fernandez2016), perhaps by exploiting variation in state campaign finance policy (Barber Reference Barber2016; La Raja and Schaffner Reference La Raja and Schaffner2015) or election timing (Anzia Reference Anzia2011). Others might study how state democracy is affected by declining state and local politics journalism (Moskowitz Reference Moskowitz2021) or by voters’ attitudes toward democratic institutions (Graham and Svolik Reference Graham and Svolik2020; Miller and Davis Reference Miller and Davis2020; Welzel Reference Welzel2007). There is especially great potential for behavioral scholars of race and ethnic politics to investigate the relationship between racial attitudes, attitudes toward democracy, and state democratic performance (e.g., Jefferson Reference Jefferson2021; Mutz Reference Mutz2018; Weaver and Prowse Reference Weaver and Prowse2020). Like comparative and political economy scholarship on whether “democracy causes growth” (Acemoglu et al. Reference Acemoglu, Naidu, Restrepo and Robinson2019), scholars can also use the State Democracy Index as an explanatory variable to study the effect of democratic performance on economic performance, socioeconomic outcomes among residents, and public attitudes such as trust. Comparative scholars can use my measurement strategy to create new measures of democratic performance in subnational units in one or more other countries, potentially constructing comprehensive cross-national measures of subunit democracy in political federations.

In this article, I use the State Democracy Index to test a set of prominent theories of the causes of democratic expansion and backsliding in the US. Drawing on American and comparative democracy literatures, I develop predictions about the drivers of democratic expansion and backsliding. I estimate the effects of political competition, polarization, and racial demographic change on states’ democratic performance. The results suggest that none of these factors is central to dynamics in state democratic performance. Republican control of state government, however, consistently and profoundly reduces state democratic performance during this period.

The large effects of Republican control, contrasted with the minimal effects of within-state dynamics, address the nationalization of American politics in recent decades. Political investments by groups in the Democratic and Republican party coalitions have made the party coalitions more nationally coordinated (Grumbach Reference Grumbach2019; Hacker and Pierson Reference Hacker and Pierson2020; Hertel-Fernandez Reference Hertel-Fernandez2019). Voters are increasingly focused on national rather than state and local politics (Hopkins Reference Hopkins2018), in part due to the decline of state and local politics journalism (Martin and McCrain Reference Martin and McCrain2019; Moskowitz Reference Moskowitz2021). This transformation means that regardless of the particular circumstances or geography, state governments controlled by same party behave similarly when they take power. The Republican-controlled governments of states as distinct as Alabama, Wisconsin, Ohio, and North Carolina have taken similar actions with respect to democratic institutions.

More research is needed to link this issue of state-level democratic performance in the US to micro-level behavioral research on the relationship between social cleavages, the Republican Party, and support for democracy. The findings in this article are consistent with an important role for national (but not state-level) racial threat (e.g., Mutz Reference Mutz2018; Parker and Barreto Reference Parker and Barreto2014). Bartels (Reference Bartels2020, 22752), for instance, finds that “substantial numbers of Republicans endorse statements contemplating violations of key democratic norms, including respect for the law and for the outcomes of elections and eschewing the use of force in pursuit of political ends” and that “[t]he strongest predictor by far of these antidemocratic attitudes is ethnic antagonism—especially concerns about the political power and claims on government resources of immigrants, African-Americans, and Latinos.” However, left unexplored in this article is the role of other important social cleavages, including those based on gender, religion, and sexuality.

In contrast to my measures, cross-national measures of democracy sometimes cover much longer stretches of time. V-Dem, for instance, measures democratic performance for countries as far back as the year 1789—though this is not without its challenges (for example, during periods of rapid changes to U.S. democracy, such as during Reconstruction). Still, it is a worthy goal to construct a State Democracy Index that covers the transformational changes to the franchise, civil liberties, and other components of democracy that occurred in earlier periods of U.S. history. Keyssar (Reference Keyssar2000) and others have engaged in this kind of historical analysis of changes in voting rights.

Perhaps more importantly, a longer time frame would contextualize the magnitude of recent shifts in state-level democracy. This article provides clear evidence of important changes in democratic performance, such as the rapid decline of democracy in states such as North Carolina since 2010. But these recent changes have occurred on a narrower range of the democracy dimension than have those in earlier periods, when, for example, states differed in terms of the legality of slavery and the franchise for women. Despite some troubling examples in state-level democracy in recent years, they do not come close to the profound differences in regime type that existed between states in the eras before the twentieth-century civil rights period. At the same time, a more significant democratic collapse is likely to be presaged by the kinds of democratic backsliding described in this article—which can entrench minority rule, curtail dissent, and limit participation in democratic institutions.

This study combines what are at times disparate discussions of American democracy. I draw upon scholarship on democratic expansion and backsliding in the US and other nation-states, while also synthesizing many distinct inquiries into state-level action in election administration, gerrymandering, and observed democratic outcomes. In the use of a deep well of data, I hope that this study contributes to quantitative measurement and theory testing of large-scale, substantively profound questions in political science and political economy.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055422000934.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the American Political Science Review Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/JNV3XO.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For helpful feedback and discussions, the author thanks Zack Beauchamp, Adam Bonica, Ruth Collier, Michele Epstein, Jacob Hacker, Charlotte Hill, Hakeem Jefferson, Jamila Michener, Rob Mickey, Paul Pierson, Phil Rocco, and Eric Schickler, as well as seminar participants at American University, Johns Hopkins, Stanford CDDRL, UC Berkeley RWAP, UCLA, UCSD, University of Minnesota, University of Oregon, UW CSSS, UW WISIR, Vanderbilt, the American Democracy Collaborative, and the Democracy in the States Meeting at Princeton CSDP. I thank Chris Warshaw, Nick Stephanopoulos, and the MIT Election Lab for graciously sharing data and Steve Levitsky and Dan Ziblatt for inspiring the title of this paper.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author declares no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

The author affirms this research did not involve human subjects.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.