Do elites and citizens hold different views of the legitimacy of international organizations (IOs), and if so why? Research on this topic is rich in assumptions, but poor in rigorous answers. According to some, the contemporary rise of anti-globalist populism reflects a gap between elite and citizen views of globalization (Inglehart and Norris Reference Inglehart and Norris2017; Rodrik Reference Rodrik2018). On this argument, elites are out of touch with the general population regarding the consequences of a globalized world. According to others, the opinions of elites and citizens regarding international politics should align. On this view, elites are responsive to citizen concerns about international cooperation and in turn influence mass opinion through cues, leading to opinion congruence (Guisinger and Saunders Reference Guisinger and Saunders2017; Schneider Reference Schneider2019).

Yet, so far, we have lacked the data and theory to identify and explain elite–citizen gaps in judgments of IOs. Several studies have examined public opinion toward IOs, including a rich literature on citizen views of the European Union (EU) (Dellmuth and Tallberg Reference Dellmuth and Tallberg2015; De Vries Reference De Vries2018; Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2005; Johnson Reference Johnson2011; Voeten Reference Voeten2013). Another literature has separately considered elite opinion vis-à-vis IOs (Best, Lengyel, and Verzichelli Reference Best, Lengyel and Verzichelli2012; Binder and Heupel Reference Binder and Heupel2015; Persson, Parker, and Widmalm Reference Persson, Parker and Widmalm2019; Rosenau et al. Reference Rosenau James, Earnest, Ferguson and Holsti2006; Verhaegen, Scholte, and Tallberg Reference Verhaegen, Scholte and Tallberg2021). However, research that compares citizen and elite views of international cooperation is extremely limited—and then only examines a single country or a single IO (Hooghe Reference Hooghe2003; Kertzer Reference Kertzer2020; Page and Bouton Reference Page and Bouton2007).

This article offers the first systematic comparative analysis of elite and citizen views of global governance. We specifically examine perceptions of IO legitimacy—that is, the extent to which elites and citizens consider an IO’s authority to be appropriate (Hurd Reference Hurd2007; Tallberg, Bäckstrand, and Scholte Reference Tallberg, Bäckstrand and Scholte2018; Zürn Reference Zürn2018).Footnote 1 Establishing whether, how far, and why elites and citizens diverge in their perceptions of IO legitimacy matters for both research and politics. Measuring this gap and locating its sources contributes to knowledge on why the political attitudes of elites and citizens differ, and could inform efforts to address this divide.

We analyze elite–citizen divergences on the legitimacy of global governance using two uniquely coordinated surveys that cover multiple IOs, countries, and elite types. On the one hand, we have inserted a battery of questions in the most recent wave of the World Values Survey (WVS7), undertaken during 2017–2019, measuring citizen attitudes toward six prominent IOs: the International Criminal Court (ICC), International Monetary Fund (IMF), United Nations (UN), World Bank (WB), World Health Organization (WHO), and World Trade Organization (WTO). On the other hand, we have simultaneously conducted an elite survey with questions parallel to the WVS7 in five diverse countries around the world—Brazil, Germany, Philippines, Russia, and United States—measuring attitudes among six types of elites—bureaucratic, business, civil society, media, political party, and research (Verhaegen et al. Reference Verhaegen, Dellmuth, Scholte and Tallberg2019). We use these data to identify elite–citizen gaps in aggregate and to explain variation in legitimacy gaps at the level of elite–citizen dyads.

Theoretically, we develop an individual-level approach to explaining elite–citizen gaps in IO legitimacy beliefs. This perspective starts from individuals as the unit of analysis, theorizes why individuals with varying characteristics think differently about IO legitimacy, and attributes elite–citizen gaps in legitimacy beliefs to the varying distribution of those characteristics across these two classes of individuals. Specifically, we theorize how differences between elites and the general public in four individual-level characteristics—socioeconomic status, political values, geographical identification, and domestic institutional trust—lead the two groups to adopt diverging views of the legitimacy of IOs. We distinguish our individual-level approach from organizational- and societal-level explanations, which locate the sources of legitimacy respectively in the features of governing institutions and in the wider social order. At the same time, our selection of IOs and countries allows us to assess individual-level explanations in diverse organizational and societal contexts.

Our central findings are twofold. First, elites indeed tend to consider IOs more legitimate than the general public, confirming the existence of an elite–citizen gap. With striking consistency, this divergence in opinion prevails for all six IOs, four of five countries, and all six elite types examined. At the same time, the data show interesting variations between contexts in the size of the divide. This gap suggests that global governance may confront problems of democratic accountability, as elites (who conduct the global governing) consistently accord more legitimacy to IOs than citizens at large. The gap also highlights a significant challenge for contemporary international cooperation, as the general population appears to be more skeptical of IOs than elite circles. The gap moreover clarifies why populist politicians around the world can take advantage from targeting IOs with antiglobalist messages.

Second, we find that this legitimacy gap is associated with systematic differences between elites and citizens regarding our four privileged individual-level characteristics. The results show substantial support for all four explanations, albeit with variation across organizational and country contexts. While differences in domestic institutional trust are a key explanation of legitimacy gaps in nearly all settings, socioeconomic status and political values matter especially for economic IOs and in the US, whereas geographical identification is particularly relevant for gaps in Russia. These findings suggest that differences at the individual level play a prominent part in explaining the elite–citizen gap in IO legitimacy. Moreover, we find that such drivers are sensitive to organizational and societal contexts, underlining the importance of comparative designs. Finally, the results show that these factors often operate concurrently, thereby challenging common portrayals that these explanations are competing (Hainmueller and Hiscox Reference Hainmueller and Hiscox2006; Scheve and Slaughter Reference Scheve and Slaughter2001).

Is There an Elite–Citizen Gap in IO Legitimacy Beliefs?

We assess the extent of elite–citizen gaps in IO legitimacy based on a careful selection of organizations and countries. These samples are constructed to ensure diversity in contextual conditions that may matter for the sizes and sources of elite–citizen legitimacy gaps. When we observe commonalities in descriptive and explanatory findings across these diversified IOs and countries, we can be more confident that we capture general dynamics. Conversely, when we observe divergent results, we should explore the contextual characteristics that may have contributed to such variation. However, the samples are not representative, so one must be careful about generalizing beyond these IOs and countries.

In terms of IOs, we focus on the ICC, IMF, UN, WB, WHO, and WTO. This selection allows us to explore elite–citizen gaps in organizations with varying characteristics, often expected to shape legitimacy beliefs (Bernauer, Mohrenberg, and Koubi Reference Bernauer, Mohrenberg and Koubi2020; Tallberg and Zürn Reference Tallberg and Zürn2019). First, these IOs govern different policy fields. Three are involved in economic governance—the IMF (macroeconomic stability), WB (development), and WTO (trade)—while three others are engaged in human security governance—the ICC (war crimes), UN (peace and security), and WHO (health). Second, these IOs vary in central institutional features, notably their decision-making procedures and their outputs. At the same time, these IOs are similar in ways that are productive for our study. All are global IOs, which is required if we wish to compare legitimacy beliefs toward the same organizations in countries around the world. All six are also relatively well known to both citizens and elites, which is a precondition for individuals to form legitimacy beliefs toward an institution. Finally, all selected IOs are key governing organizations within their respective policy domains, lending political importance to our inquiry.

In terms of countries, we compare elite and citizen views in Brazil, Germany, the Philippines, Russia, and the United States. This selection allows us to examine elite–citizen gaps under diverse societal conditions, frequently expected to influence legitimacy beliefs (Inglehart and Welzel Reference Inglehart and Welzel2005; Norris Reference Norris1999). First, these countries exhibit variation in economic development and political regime. While Germany and the US are high-income economies, Brazil and Russia are upper-middle-income economies, and the Philippines a lower-middle-income economy (World Bank 2021). Similarly, Germany and the US are liberal democracies, while Brazil is an electoral democracy, and the Philippines and Russia electoral autocracies (V-Dem 2020). Second, these countries vary in their experiences of the six IOs in focus. Each country has a particular power position within a given IO, based on both formal procedures and informal practices (Tallberg and Verhaegen Reference Tallberg and Verhaegen2020). Likewise, each country has specific experiences of the policies of these IOs, for instance, having received IMF loans, feared ICC prosecution, or felt WTO trade effects.

To measure citizen attitudes, we use data from the WVS7, conducted between October 2017 and December 2019 (WVS 2019). The WVS7 employs random probability sampling to arrive at nationally representative samples of the adult population in a country (Appendix A1). The sample sizes for the five countries in this study are 1,762 in Brazil, 1,528 in Germany, 1,200 in the Philippines, 1,810 in Russia, and 2,596 in the US. The WVS7 mainly used computer-assisted personal interviews in Brazil and Germany, paper-and-pencil interviews in the Philippines and Russia, and computer-assisted web interviews in the US (Appendix A2).

To measure elite attitudes, we use data from the LegGov Elite Survey that we fielded largely simultaneously in the five countries between October 2017 and August 2019 (Appendix A3). The elite survey was undertaken concurrently with the WVS7, but over a longer period, due to the greater challenge of reaching elites.Footnote 2 We define elites as persons who hold leading positions in key organizations in society that strive to be politically influential. Elites are thus generally more proactive and powerful in governance than citizens at large. While most studies of elite opinion focus exclusively on political elites, our survey also encompasses wider societal elites. Both governmental and nongovernmental actors aspire to shape contemporary global governance (e.g., Avant, Finnemore, and Sell Reference Avant, Finnemore and Sell2010); thus, it is important to establish and explain any gaps involving societal as well as political elites. Among political elites, the survey covers leaders in government bureaucracy and political parties. Among societal elites, the survey covers leaders in business, civil society, media, and research.

For the selection of elite interviewees, we used quota sampling, as it offers advantages in identifying and balancing elite respondents. Because no exhaustive database of elite individuals and organizations is available, it was not possible to draw a random sample. Instead, we identified prospective interviewees with a targeted selection procedure, based on their position within relevant organizations (Hoffmann-Lange Reference Hoffmann-Lange, Dalton and Klingemann2009). The sample is thus not representative for elites in these countries, and caution is required when generalizing beyond our sample.

We interviewed at least 100 elites per country. Each country subsample consists of at least 25 bureaucratic elites, 25 political party elites, 12 business elites, 13 civil society elites, 12 media elites, and 13 research elites. The quotas for the political elite types are higher, as these circles are usually most directly involved in decision-making vis-à-vis IOs. In total, we interviewed 599 elite individuals: 124 in Brazil, 123 in Germany, 122 in the Philippines, 108 in Russia, and 122 in the USA. The survey was conducted by telephone (77%) or as a self-administered online survey when a telephone interview was not possible (23%). See technical report of the LegGov Elite Survey for more information on the quota, contact, and interview procedures (Verhaegen et al. Reference Verhaegen, Dellmuth, Scholte and Tallberg2019).

To capture respondents’ perceptions of IO legitimacy, we measure their confidence in the organizations. The two surveys asked respondents about their degrees of confidence in the six IOs, with the following options: (0) “no confidence at all,” (1) “not very much confidence,” (2) “quite a lot of confidence,” or (3) “a great deal of confidence.” The confidence measure has two distinct advantages. First, it aligns well with our conceptualization of legitimacy as the belief that an institution holds appropriate authority. By capturing general faith in an institution, confidence taps into a reservoir of foundational support that is indicative of legitimacy (Easton Reference Easton1975). Other studies that use a multi-item measure usually invoke a broader conceptualization of legitimacy—for example, incorporating normative standards to be met by an institution and/or acceptance of its rules (e.g., Norris Reference Norris1999). Second, the confidence measure allows us to link our study to the large literature on public opinion that uses this indicator of legitimacy, thus facilitating scientific cumulation. Confidence, along with trust, has emerged in comparative politics and international relations as a common way to measure legitimacy beliefs (Caldeira Reference Caldeira1986; Dellmuth and Tallberg Reference Dellmuth and Tallberg2015; Inglehart and Welzel Reference Inglehart and Welzel2005; Norris Reference Norris, Esmer and Pettersson2009; Voeten Reference Voeten2013).

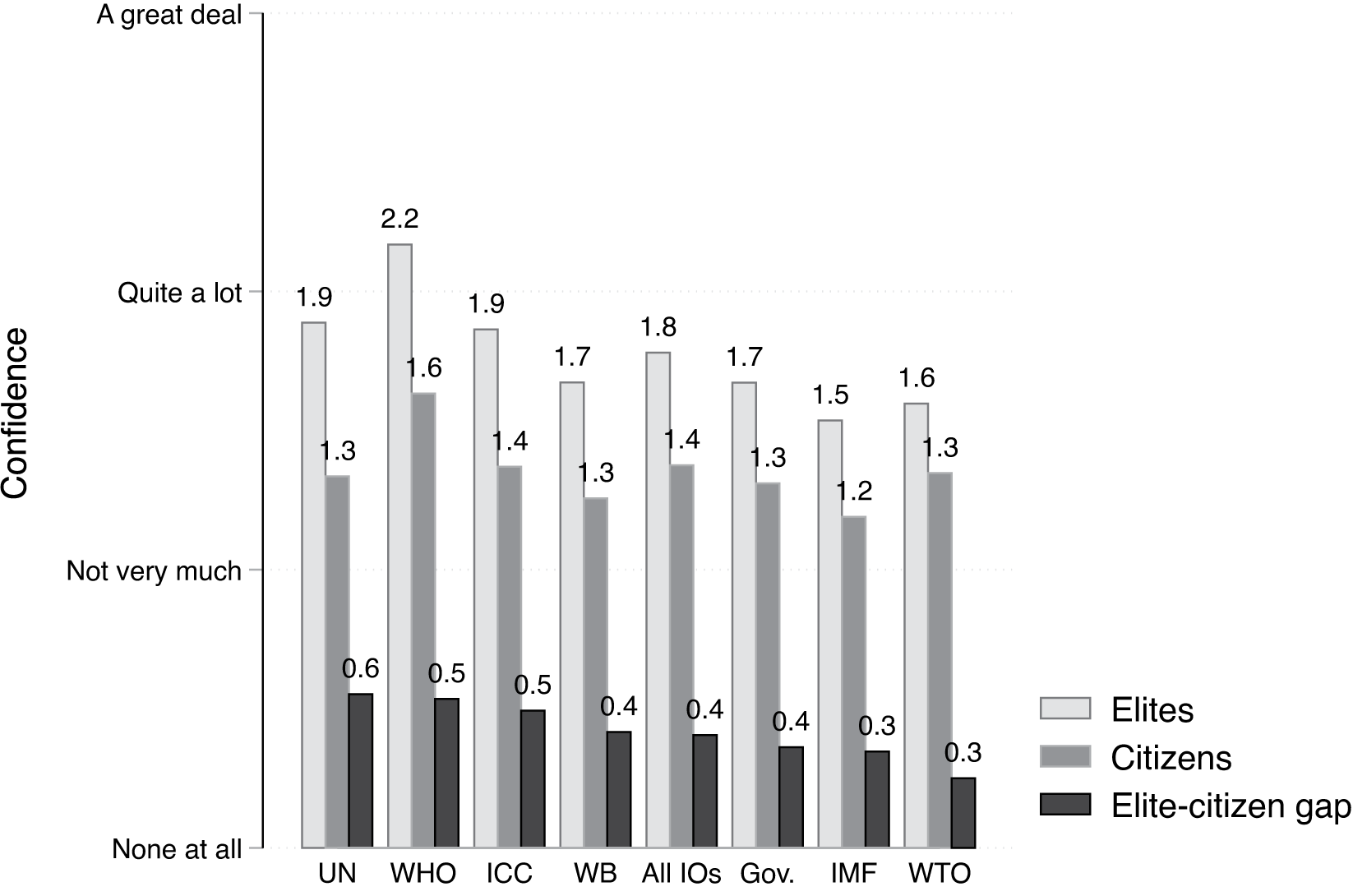

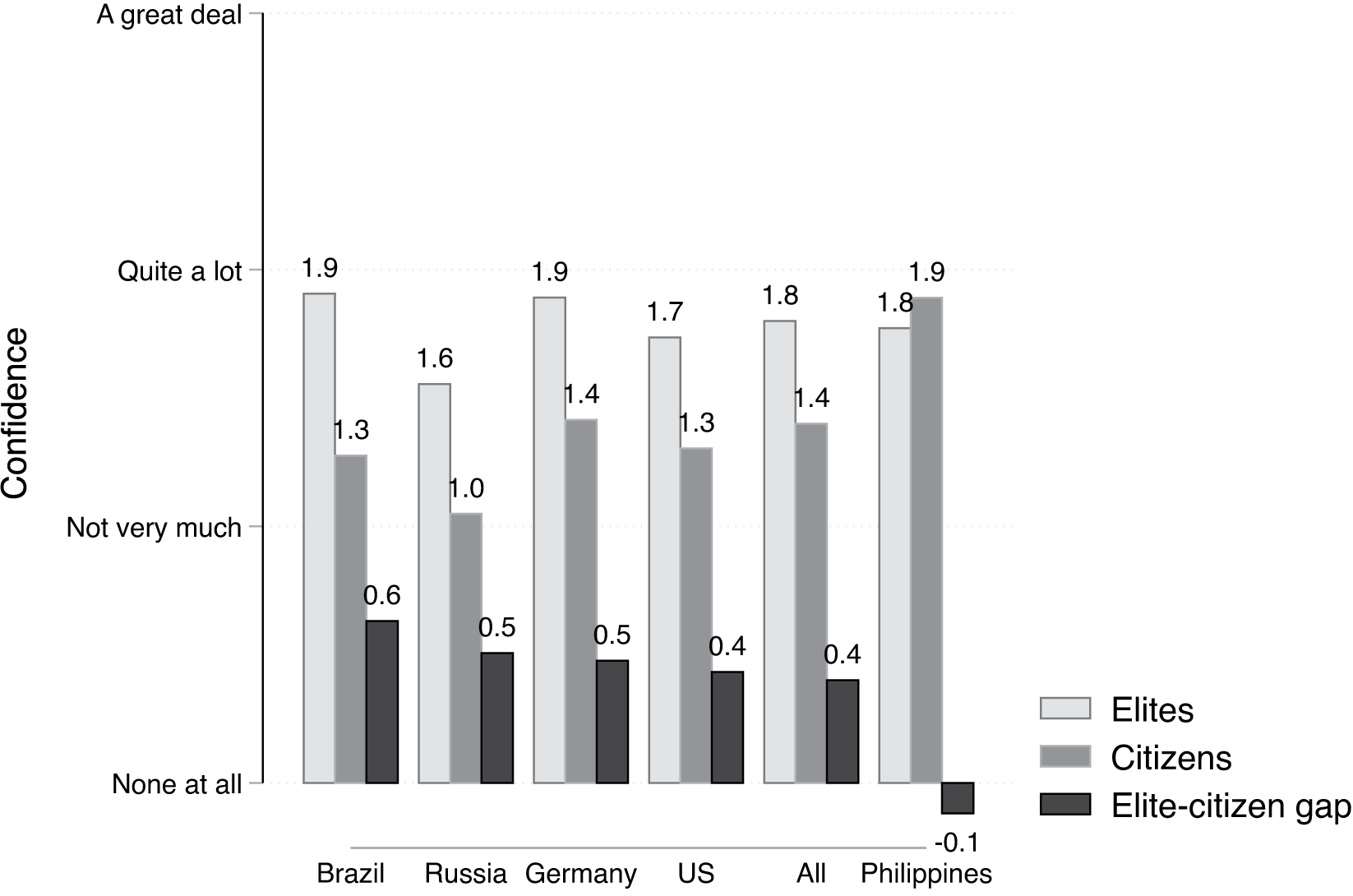

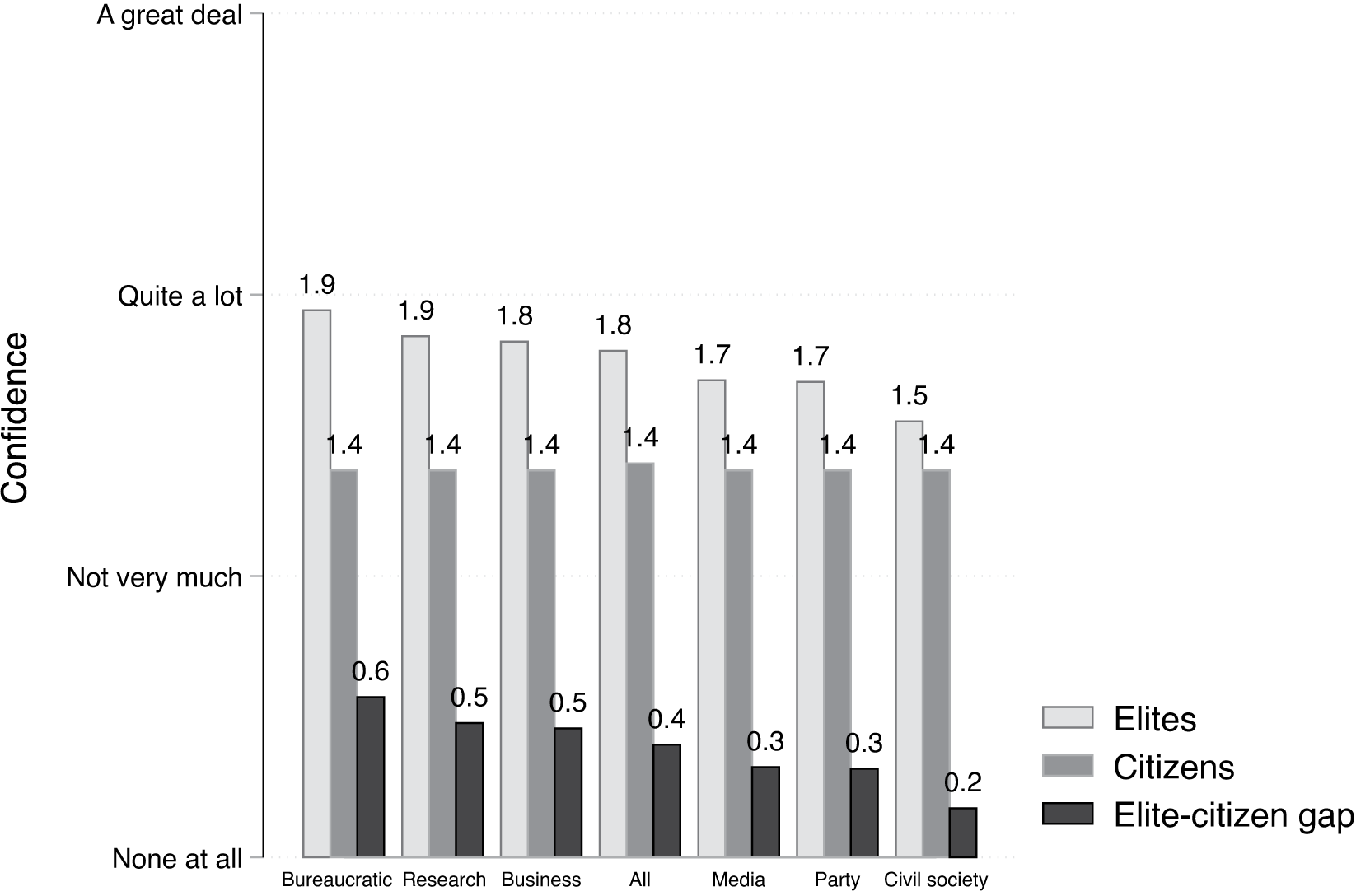

Figures 1–3 compare elite and citizen perceptions of IO legitimacy based on the two surveys. The data show that, on average, elites tend to have more confidence in IOs compared with citizens at large, confirming the existence of a gap in legitimacy beliefs. This divergence between elite and citizen views holds for all six IOs (Figure 1), for four of the five countries (Figure 2), and for all six elite types (Figure 3). At the same time, the data point to interesting variations in the size of the gap across IOs, countries, and elite types.

Figure 1. Legitimacy Gap by IOs and National Government

Note: Graph shows mean values for all five countries, comparing elites with citizens in their respective countries. Differences in mean confidence between elites and citizens are statistically significant for each IO (p < 0.001). Due to rounding, some totals for the average gap may not correspond with the difference between the elite and citizen averages.

Figure 2. Legitimacy Gap by Country

Note: Graph shows mean values encompassing all IOs, comparing elites with citizens in their respective countries. Differences in mean confidence between elites and citizens are statistically significant for each country (p < 0.05 for the Philippines, p < 0.001 for the other countries). Due to rounding, some totals for the average gap may not correspond with the difference between the elite and citizen averages.

Figure 3. Legitimacy Gap by Elite Type

Note: Graph shows mean values for all IOs, comparing elite types with citizens. Differences in mean confidence are statistically significant for each elite type (p < 0.001). Due to rounding, some totals for the average gap may not correspond with the difference between the elite and citizen averages.

Figure 1 pools the data from all countries and elite types to show the size of the elite–citizen gap for all six IOs combined, each IO individually, and (as a point of comparison) the national governments in the five countries. On a scale from 0 (no confidence at all) to 3 (a great deal of confidence), the mean confidence among citizens for all six IOs combined is 1.4, while the mean confidence among elites is 1.8. The gap of 0.4 implies that the surveyed elites on average have 30% more confidence in these IOs than the surveyed citizens. The gap is also significant for each IO, with the largest divergence in respect of the UN (0.6) and smallest in respect of the WTO (0.3). That said, these elite–citizen gaps are not limited to IOs, as a similar gap in confidence prevails for national governments (0.4).

Figure 2 displays the gap in confidence between elites and citizens in the five countries viewed separately, pooling responses across all IOs and elite types. The gap is largest in Brazil (0.6) and smallest in the Philippines, where the gap is actually negative (-0.1), as elites are on average slightly more skeptical than citizens. The pattern for the Philippines deviates because citizens in this country are more positive than elites toward the economic IOs (IMF, WB, WTO) while having nearly as much confidence as elites in the other IOs. Moreover, citizens in the Philippines have higher overall confidence in IOs than citizens in the other four countries. This pattern also appeared in waves 3, 4, and 6 of the WVS, when Philippine respondents expressed higher confidence in the UN than those in Brazil, Germany, Russia, and the US.Footnote 3

Figure 3 presents the gap in relation to different elite types, pooling responses across all IOs and countries. Although there is a gap in confidence for each type of elite, it ranges from largest with respect to bureaucratic elites (0.6) to smallest for civil society elites (0.2). These differences in mean gaps between elite types are statistically significant in all combinations (p < 0.001), except for the difference between media and political party elites (p < 0.05).

Explaining the Gap: An Individual-Level Approach

Having established the pervasive presence of an elite–citizen gap in IO legitimacy beliefs, we now theorize ways to explain it. Prima facie this contrast in attitudes need not be so surprising, as elites and the wider population tend to inhabit different life-worlds (Gerring et al. Reference Gerring, Oncel, Morrison and Pemstein2019; Hartmann Reference Hartmann2006). Yet what, more specifically, explains why elites on average find IOs more legitimate than the overall population?

Scholarship suggests three alternative ontological starting points for theorizing legitimacy in global governance: the individual, the organization, and the social structure (Tallberg, Bäckstrand, and Scholte Reference Tallberg, Bäckstrand and Scholte2018). Individual-level explanations attribute legitimacy beliefs to circumstances of the person holding them, such as interest calculations, political values, and identity constructions (e.g., Dellmuth Reference Dellmuth, Tallberg, Bäckstrand and Scholte2018; Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2005). Organizational-level explanations suggest that legitimacy beliefs arise from the features of governing institutions, such as their purposes, procedures, and performances (e.g., Bernauer, Mohrenberg, and Koubi Reference Bernauer, Mohrenberg and Koubi2020; Tallberg and Zürn Reference Tallberg and Zürn2019). Societal-level explanations locate sources of legitimacy beliefs in characteristics of the wider social order, such as cultural norms, economic systems, and political regimes (e.g., Gill and Cutler Reference Gill and Cutler2014; Scholte Reference Scholte, Tallberg, Bäckstrand and Scholte2018).

Here we develop an individual-level approach to explaining the elite–citizen gap in IO legitimacy beliefs. This approach has several advantages. First, it recognizes that legitimacy is a belief in the minds of individuals and varies between individuals, thus meriting careful examination of the conditions of individuals (Easton Reference Easton1975). Second, an individual-level approach allows for a coherent argument that starts from individuals as the unit of analysis, theorizes why certain characteristics lead individuals to hold different positions on IO legitimacy, and ascribes the elite–citizen gap in legitimacy to the distribution of these characteristics across these two groups of individuals (cf. Kertzer Reference Kertzer2020). Third, an individual-level approach makes it possible to assess a variety of factors from debates in comparative politics (Inglehart and Norris Reference Inglehart and Norris2017; Rodrik Reference Rodrik2018), international relations (Hainmueller and Hiscox Reference Hainmueller and Hiscox2006; Scheve and Slaughter Reference Scheve and Slaughter2001), and EU studies (Hobolt and de Vries Reference Hobolt and De Vries2016; Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2005). This literature often presumes these factors to be competing, but our integrated perspective also allows that they could be complementary in explaining legitimacy gaps.

Our account suggests that elites and general publics are composed of individuals who vary systematically in characteristics that matter for their attitudes toward IOs, resulting in the observed gap in legitimacy beliefs. Specifically, we theorize four types of individual characteristics: socioeconomic status, political values, geographical identification, and domestic institutional trust. We focus on these four characteristics because they are complementary theoretically, as each highlights one major dimension of an individual: their material standing, value orientation, identity construction, and institutional trust. In addition, earlier research has found each characteristic to matter for international attitudes in specific empirical settings (e.g., Dellmuth and Tallberg Reference Dellmuth and Tallberg2020; de Wilde et al. Reference de Wilde, Koopmans, Merkel, Strijbis and Zürn2019; Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2005; Scheve and Slaughter Reference Scheve and Slaughter2001), making them reasonable candidates for our general account of elite–citizen gaps. When bringing these characteristics together in one integrated framework, we cover under one roof perhaps the most important ways in which individuals differ from each other with implications for legitimacy beliefs. Yet, recognizing that other theories might privilege other individual characteristics, our empirical analysis also considers age, gender, social trust, and political knowledge as alternative explanations.

We assume that elites and general publics display compositional differences due to prior processes of selection and socialization (Hooghe Reference Hooghe2005; van Zanten Reference Van Zanten, Apple, Ball and Gandin2010). For instance, in terms of selection, people who have a stronger socioeconomic position and have greater trust in existing governmental institutions may be more likely to seek and secure elite roles in politics and society. Similarly, in terms of socialization, people in elite positions may be more likely to assume a liberal political outlook and develop a global identification. Together, these processes make elites as a group different from the general population, with implications for their attitudes toward IOs.

While taking the individual as our starting point, we recognize that persons are socially embedded, such that organizational and societal conditions may also shape legitimacy beliefs. This insight informs our account in two respects. First, we acknowledge that a focus on individual characteristics involves bracketing the broader processes that may have led a person to hold a certain socioeconomic status, political value, geographical identification, and institutional trust. Second, we are open to the possibility that individual-level explanations may vary in strength across organizational and societal contexts and build on our unique comparative design to explore such variation. Thus, in the interpretations of our results, we discuss the role that IO and country circumstances may play in shaping explanatory patterns observed at the individual level.

These qualifications also indicate the limits of an individual-level approach. Politics is not reducible to individuals: institutions and structures generate their own distinct forces (List and Spiekermann Reference List and Spiekermann2013). Thus, while analysis at the individual level can provide substantial and important insights into the dynamics of legitimacy beliefs, it does not offer a complete explanation.

The next subsections elaborate our four expectations. For each characteristic, we develop a hypothesis that expresses in dyadic terms how differences between elites and citizens in the specific characteristic could lead to differences in their respective legitimacy beliefs.

Socioeconomic Status

Our first expectation suggests that differences in socioeconomic status between elites and citizens contribute to gaps in their respective legitimacy beliefs toward IOs. This argument draws on research that emphasizes utilitarian calculation and people’s position in the economy as central to the formation of opinions on international matters (Rodrik Reference Rodrik2018; Scheve and Slaughter Reference Scheve and Slaughter2001). Institutions and their policies produce uneven economic consequences for affected parties, depending on their skills and resources, and these differential effects lead people to adopt varying attitudes toward trade, investment, migration, institutions, and globalization generally. This research usually derives expectations about people’s attitudes from distributive models, observed economic effects, or perceptions of economic status (Curtis, Jupille, and Leblang Reference Curtis, Jupille and Leblang2014; Scheve and Slaughter Reference Scheve and Slaughter2001). In the context of IOs, this logic has presented an influential explanation of citizen attitudes toward the EU (Anderson and Reichert Reference Anderson and Reichert1995; Gabel Reference Gabel1998).

We build on this logic to suggest that differences in how elites and citizens are positioned to benefit materially from IOs can help to explain corresponding differences in their legitimacy beliefs toward these organizations. Elites are commonly believed to gain more from economic globalization than the general population in terms of employment opportunities, financial investments, and so on. Elites tend to have greater human and financial capital, making them better placed than the broader public to benefit from a globalized economy (Gerring et al. Reference Gerring, Oncel, Morrison and Pemstein2019), which may help to explain why elites tend to conceive of IOs as more legitimate. Compared with citizens, elites more often belong to the winners of contemporary globalization—a situation that existing IOs both reflect and help to generate. At a dyadic level, we therefore hypothesize that

Hypothesis 1: The higher the socioeconomic status of an elite individual compared with that of a citizen, the more legitimate this elite will find an IO compared with this citizen.

Political Values

Our second expectation suggests that elite–citizen gaps regarding IO legitimacy reflect differences in political values. This expectation builds on research that documents an effect of political ideology on attitudes toward international matters (de Wilde et al. Reference de Wilde, Koopmans, Merkel, Strijbis and Zürn2019; Hooghe, Lenz, and Marks Reference Hooghe, Lenz and Marks2019; Inglehart and Norris Reference Inglehart and Norris2017).

This literature argues that contestation over international issues follows one or several lines of value conflict. Some studies maintain that the left–right spectrum, so prominent in domestic politics, also structures attitudes toward international affairs (Hooghe, Marks, and Wilson Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002; Noël and Thérien Reference Noël and Thérien2008). Others affirm the relevance of another axis of ideological contestation—namely, between green, alternative, and liberal (GAL) values on the one hand and traditional, authoritarian, and nationalist (TAN) values on the other (Hooghe, Lenz, and Marks Reference Hooghe, Lenz and Marks2019; Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi, Grande, Lachat, Dolezal, Bornschier and Frey2006). The GAL-TAN scale captures attitudes on prominent contemporary issues that often fit poorly on the left–right axis, such as immigration, gender equality, ecological concerns, and national sovereignty.

We build on research that links these value dimensions to international attitudes and finds that individuals who hold right-wing or TAN values tend to have more negative attitudes toward international cooperation than individuals who espouse left-wing or GAL values (de Wilde et al. Reference de Wilde, Koopmans, Merkel, Strijbis and Zürn2019; Hainmueller and Hiscox Reference Hainmueller and Hiscox2006; Hooghe, Lenz, and Marks Reference Hooghe, Lenz and Marks2019; Inglehart and Norris Reference Inglehart and Norris2017). Our expectation invokes this logic, suggesting that differences between elites and citizens in political values help to explain differences in the perceived legitimacy of IOs. If elites more often hold political values that are linked to support for international cooperation, this may explain why they also generally accord more legitimacy to IOs than citizens at large. The recent wave of right-wing and TAN populism suggests that contemporary general publics indeed may lean more toward antiglobalist ideology, with its skepticism of IOs, whereas elites on average incline more to ideological positions sympathetic to IOs. At a dyadic level, we thus expect that

Hypothesis 2: The more that an elite individual holds left-wing or green-alternative-liberal political values than a citizen, the more legitimate this elite will find an IO compared with this citizen.

Geographical Identification

Our third expectation suggests that the gap in legitimacy beliefs toward IOs arises from differences between elites and citizens at large in terms of the geographical spheres to which they feel attached. This expectation draws on research concerning social identity in general, and geographical identification in particular, as a source of attitudes toward international issues and institutions (Norris Reference Norris, Esmer and Pettersson2009; Rosenau et al. Reference Rosenau James, Earnest, Ferguson and Holsti2006). This line of argument has figured particularly in studies that explain public opinion toward the EU (Carey Reference Carey2002; Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2005).

This logic suggests that public support for international governance aligns more with a global identification than a national disposition. Individuals with a global identification are assumed to favor international governance because it links political authority with the global community to which they feel attached, whereas individuals who feel closer to their country tend to view IOs as a lower priority or even as a threat to national identity and autonomy (Verhaegen et al. Reference Verhaegen, Hoon, Kelbel, Van Ingelgom and Deschouwer2018). Empirically, research has found that individuals with a stronger European identity are more supportive of the EU than individuals with trenchant national identities (Carey Reference Carey2002; Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2005). In the context of the UN, too, people who identify with the world are more positively predisposed toward that IO (Dellmuth and Tallberg Reference Dellmuth and Tallberg2015).

Building on this logic, we suggest that a greater prevalence of global identification among elites relative to citizens at large could help to explain the gap between their average IO legitimacy beliefs. Elites, on average, tend to hold greater global attachments, since individuals in leadership positions likely gain more global exposure than citizens in general through greater international travel, higher education, larger competence in foreign languages, and so on (Rosenau et al. Reference Rosenau James, Earnest, Ferguson and Holsti2006). In addition, people who identify more with the global sphere are more likely to seek and obtain elite positions in today’s increasingly internationalized academia, business, civil society, government, media, and politics. We expect this likely difference in geographical identification between elites and citizens to matter for legitimacy beliefs. At a dyadic level, we expect that

Hypothesis 3: The more an elite individual holds a global identification compared with a citizen, the more legitimate this elite will find an IO compared with this citizen.

Domestic Institutional Trust

Our fourth expectation explains the elite–citizen gap in IO legitimacy beliefs by differences in levels of trust toward domestic political institutions. This expectation draws on research that highlights linkages between attitudes toward domestic and international governance institutions. This literature shows strong positive correlations between individuals’ trust in domestic political institutions and their trust in IOs as diverse as the EU, ICC, IMF, UN, and WTO (Dellmuth and Tallberg Reference Dellmuth and Tallberg2020; Harteveld, van der Meer, and De Vries Reference Harteveld, van der Meer and De Vries2013; Johnson Reference Johnson2011; Voeten Reference Voeten2013).Footnote 4

Past studies invoke three types of mechanisms to explain this link. Some research suggests that individuals use their trust in domestic political institutions as a heuristic. Because most people have less awareness of IOs, they draw on their assessments of domestic political institutions, which they know better, as a shortcut to opinions about IOs (Harteveld, van der Meer, and De Vries Reference Harteveld, van der Meer and De Vries2013). Other studies argue that trust in both national and international governance institutions reflects a common antecedent factor: generalized trust. On this account, people rely on their overall trust predisposition when forming opinions about governing institutions on all levels (Dellmuth and Tallberg Reference Dellmuth and Tallberg2020). Still others place the driver with the role of one’s government in IOs. If people greatly (mis)trust the national government, and this government is influential within an IO, then people (mis)trust that international institution as well (Harteveld, van der Meer, and De Vries Reference Harteveld, van der Meer and De Vries2013).

Our expectation builds on such logics to suggest that elites are more likely to have greater trust in their domestic political institutions than citizens at large, which can help to explain the gap in IO legitimacy beliefs. Owing to elites’ advantaged positions in politics and society, they tend to hold more positive views of governing institutions than citizens in general (Bowler and Donovan Reference Bowler and Donovan2002). Elites have more access to governing bodies and thus more possibilities to influence them. Indeed, elites rather than the general public do the actual governing through these institutions. Elites therefore ought to find domestic political institutions—and by extension IOs—more legitimate than citizens. At a dyadic level, we thus expect that

Hypothesis 4: The more trust an elite individual has in domestic political institutions compared with a citizen, the more legitimate this elite will find an IO compared with this citizen.

Empirical Analysis

We now proceed to an empirical analysis of our individual-level approach, focused on these four hypotheses. We begin by briefly explaining the models and measurements we use and then present the results.

Model Specification and Operationalization

We use a dyadic modeling strategy (cf. Lindgren, Inkinen, and Widmalm Reference Lindgren, Inkinen and Widmalm2009) whereby each elite respondent is matched to all citizen respondents in their country. The observations in the analyses thus concern elite–citizen dyads, not individuals as such. The analysis tests the extent to which differences within these elite–citizen dyads regarding socioeconomic status, political values, geographical identification, and domestic institutional trust are associated with differences within the same dyads regarding confidence in IOs. The dyadic approach is therefore well suited to test our individual-level explanations of elite–citizen gaps in IO legitimacy beliefs. An alternative individual-level modeling strategy would be to test separately what factors relate to elite confidence and to citizen confidence and then to compare those two analyses. However, such an approach would not directly relate gaps in confidence levels between elites and citizens to differences between elites and citizens regarding potential explanatory factors.

In our dyadic analysis, each citizen and each elite respondent figure multiple times in the dataset. For example, a sample of 1,000 citizens and 100 elites yields a dataset with 100,000 dyads, with each elite paired with each of the 1,000 citizens in their country. This data structure means that the observed dyads are not independent of each other. To correct for this issue, we include robust standard errors clustered at the level of both citizens and elites by using cgmreg in Stata for multiway clustering (Gelbach Reference Gelbach2009; Gelbach and Miller Reference Gelbach and Miller2011).

The dependent variable confidence gap is constructed by, within each dyad, subtracting a citizen’s (j) confidence in an IO from an elite’s (i) confidence in the same IO. The average of gaps in legitimacy beliefs between elite i and citizen j for all six IOs (k) is then calculated as follows:

![]() $ {y}_{ij\hskip2pt =}\frac{\left({\sum}_{k=1}^6{i}_k-{j}_k\right)}{6} $

.

$ {y}_{ij\hskip2pt =}\frac{\left({\sum}_{k=1}^6{i}_k-{j}_k\right)}{6} $

.

The independent variables are elite–citizen differences in, respectively, socioeconomic status, political values, geographical identification, and domestic institutional trust. These differences between elites and citizens are calculated in the same way as differences in legitimacy beliefs—namely, by subtracting scores for each citizen from scores for each elite.Footnote 5

We operationalize socioeconomic status with two indicators. First, we measure respondents’ highest level of formal education on a nine-point scale from 0 to 8. A mean difference in education of about three points suggests that, on average in our sample, citizens at large have less formal education (mean of 4.1) than elites (mean of 7.0). However, the standard deviation of about 2 indicates that this difference varies considerably between dyads. Second, we estimate the difference between elites and citizens in their satisfaction with the financial situation of their household, using an indicator ranging from 1 (completely dissatisfied) to 10 (completely satisfied). There is little difference between citizens (mean of 6.2) and elites (mean of 7.0), while a standard deviation of 3 indicates much spread across dyads.

We also operationalize political values with two indicators. First, we include left–right self-placement on a scale from 1 (most left) to 10 (most right). Elites lean slightly more to the left (mean of 4.7) than citizens at large (mean of 5.4), although a standard deviation of 3 indicates much difference across dyads. Second, we build two measures based on several survey items that tap respondents’ values on the GAL-TAN scale (cf. Bauhr and Charron Reference Bauhr and Charron2018). These items cover respondents’ attitudes on personal morality (abortion, homosexuality, sex before marriage, and divorce), immigration, and the relative importance of maintaining social order. From these questions we create a composite variable that distinguishes between GAL (= 1) and TAN (= 0) positions. We calculate for each dyad whether a citizen and an elite have the same position, whether the citizen is TAN but the elite is GAL, or vice versa. The elite is GAL and the citizen TAN in about 22% of the dyads, whereas the elite is TAN and the citizen GAL in about 26% of the cases.

We include two measures for geographical identification. The survey asked respondents how close they feel to the world and to their country, each on a scale from 0 (not close at all) to 3 (very close). Surprisingly, elites less often feel close to the world (mean of 1.1) than citizens (mean of 1.4). Here, too, a standard deviation of almost 1 indicates much difference across dyads. With respect to the second indicator, elites less often feel close to their country (mean of 0.6) than citizens (mean of 2.1). Yet a standard deviation of 0.9 suggests considerable divergence across dyads.

We operationalize domestic institutional trust through two indicators. The first indicator measures confidence in the national government. The scale ranges from 0 (none at all) to 3 (a great deal). Overall, elites have greater confidence in the national government (mean of 1.7) than citizens at large (mean of 1.3), though the standard deviation of 1 indicates considerable divergence across dyads. The second indicator expresses elite–citizen differences in satisfaction with the political system of their country on a scale from 1 (not satisfied at all) to 10 (completely satisfied). Elites are somewhat less satisfied with the political system of their country (mean of 4.4) than citizens at large (mean of 5.1), although the standard deviation of 3 indicates much divergence across dyads. Finally, we control for age and gender.

Results

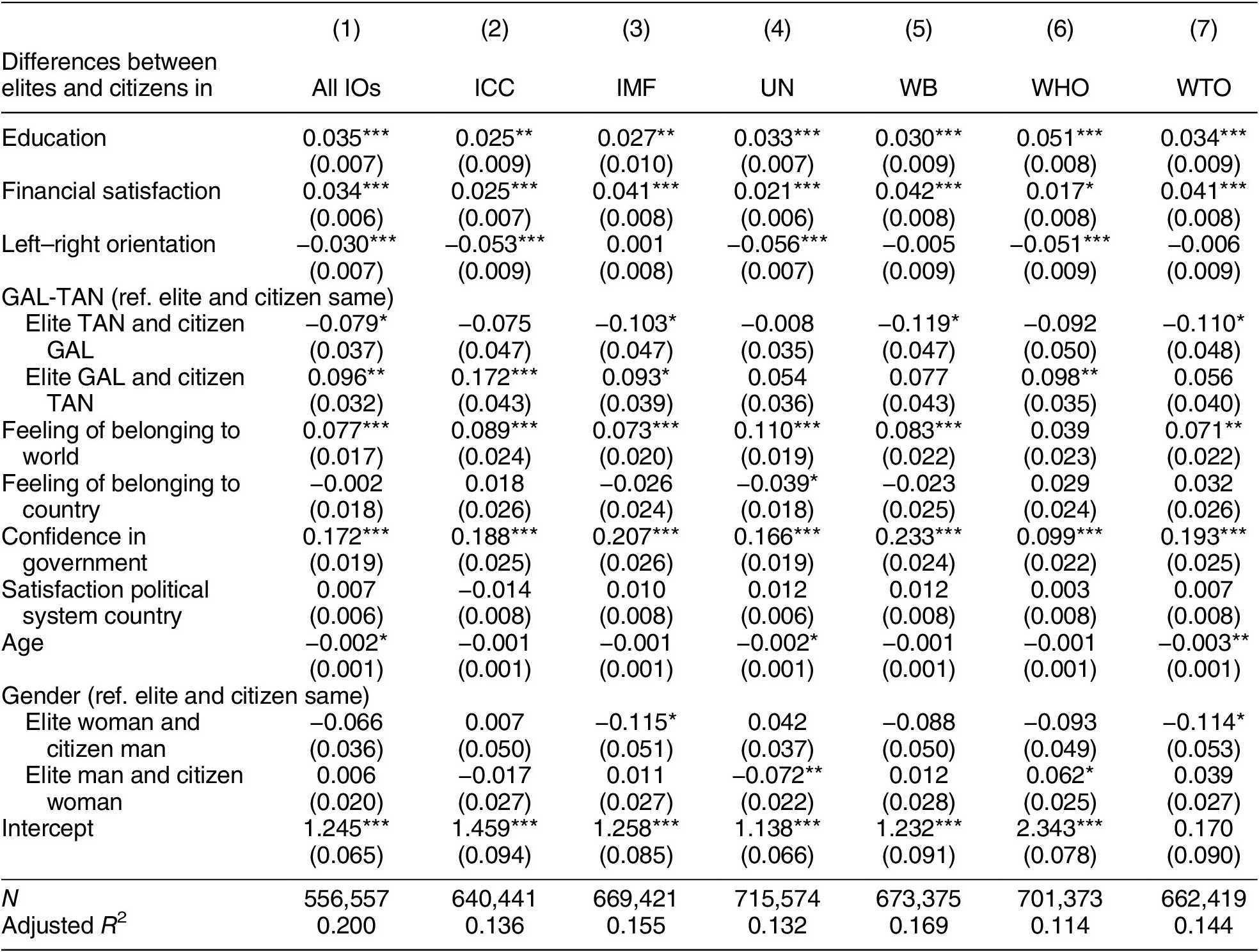

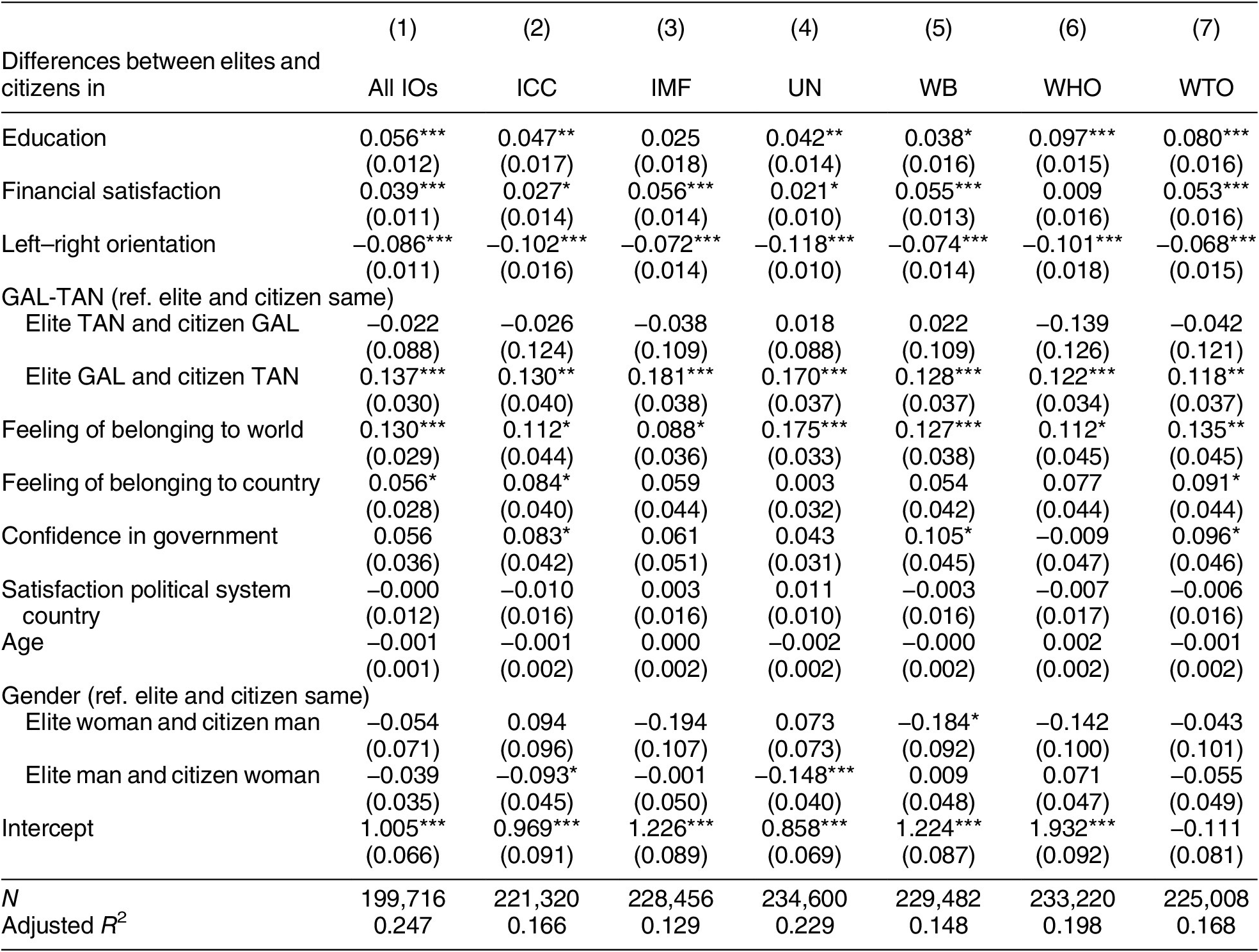

We present the findings for all countries pooled (Table 1) and then each country individually (Tables 2–6). All tables break down the data by the six IOs. We find clear support for all four individual-level explanations. At the same time, varying support in respect of particular IOs and countries suggests the relevance of organizational and societal contexts.

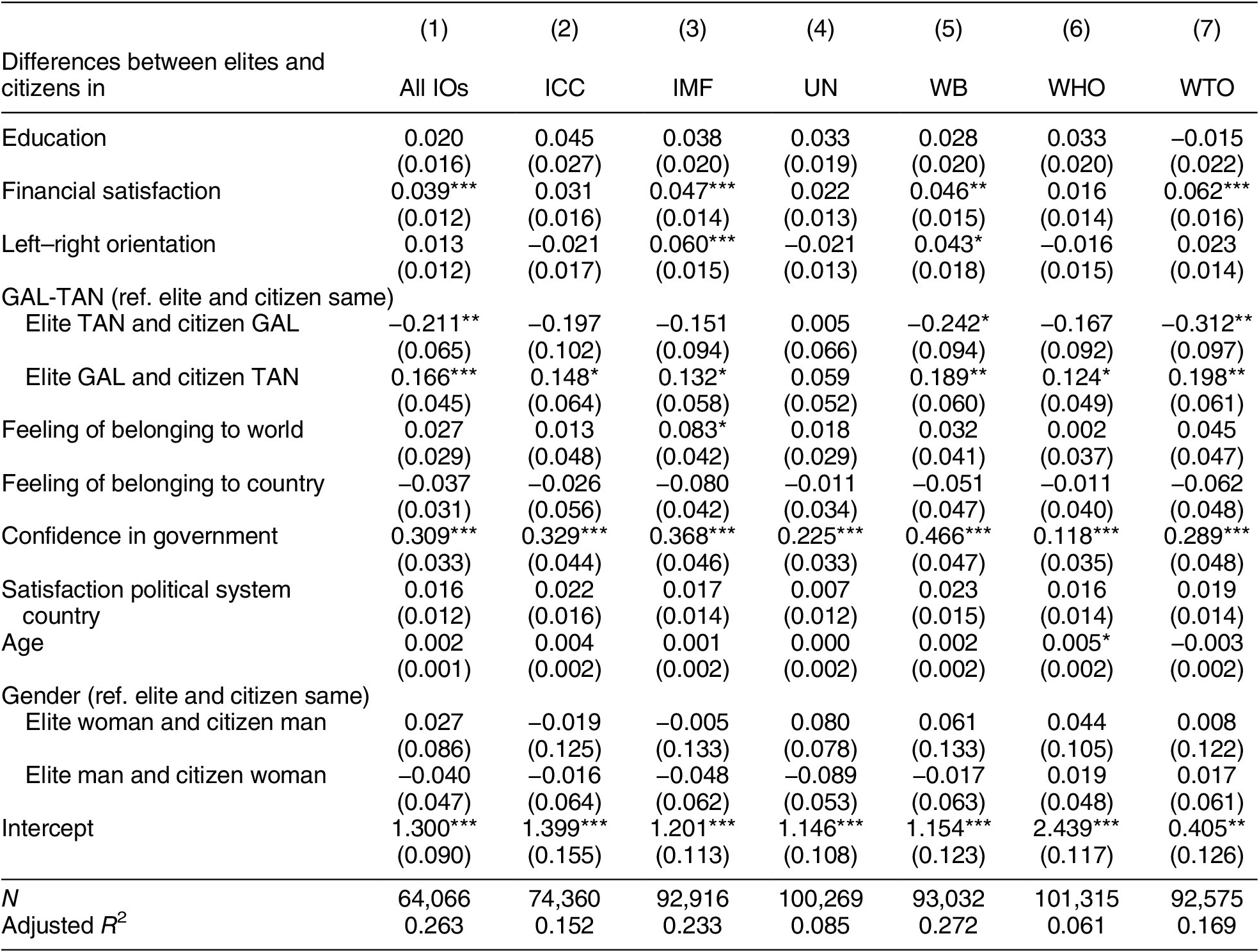

Table 1. Dyadic Analysis of Difference in Confidence in IOs in Five Countries, Pooled

Note: OLS regression using Difference in IO confidence as a dependent variable (higher values indicate greater elite confidence in IOs relative to the citizen in the dyad). Entries are unstandardized coefficients with robust standard errors in parentheses, clustered at the level of citizens and elites. Country fixed effects are included. Significance levels: *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

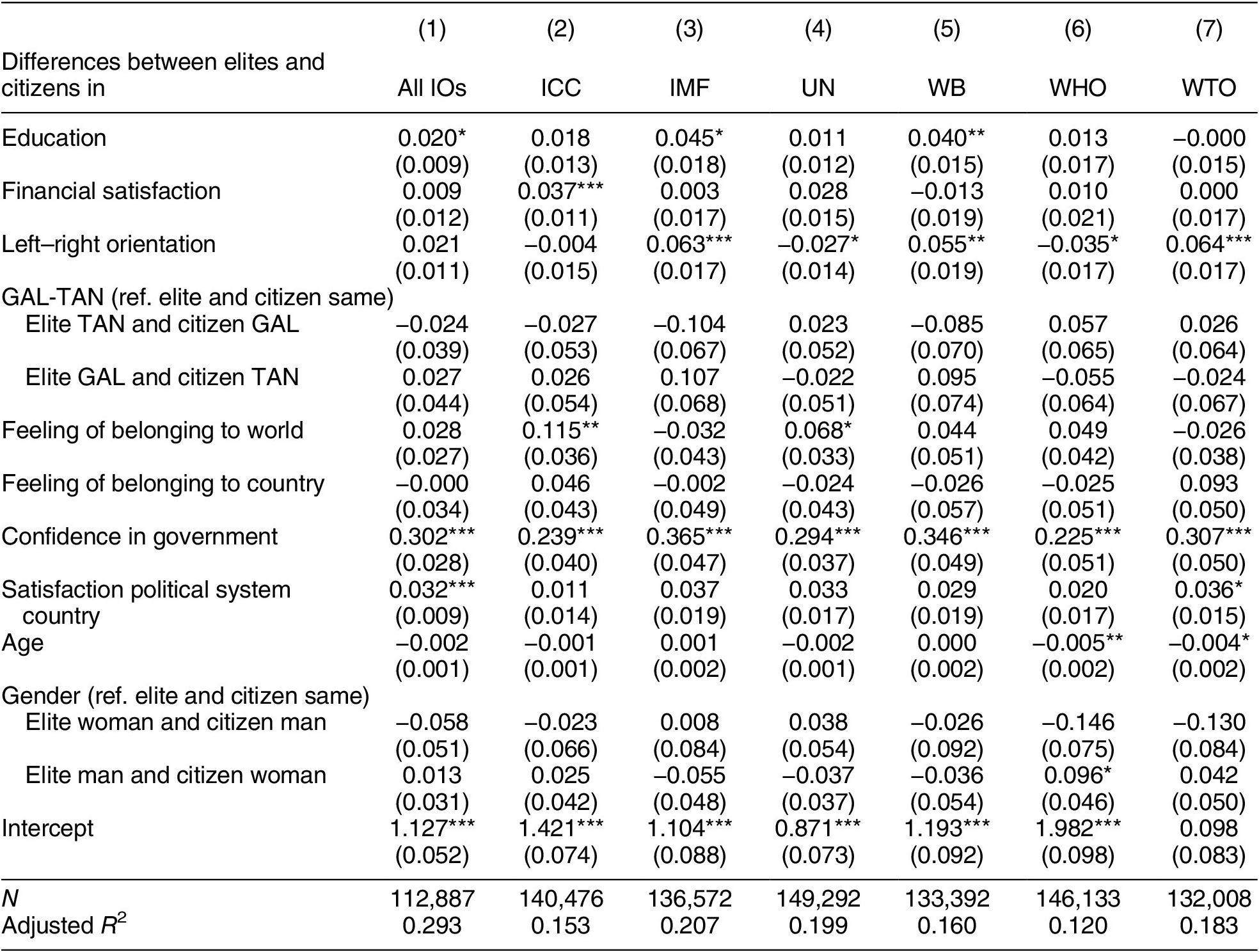

Table 2. Dyadic Analysis of Difference in Confidence in IOs in Brazil

Note: OLS regression using Difference in IO confidence as a dependent variable (higher values indicate greater elite confidence in IOs relative to the citizen in the dyad). Entries are unstandardized coefficients with robust standard errors in parentheses, clustered at the level of citizens and elites. Significance levels: *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Table 3. Dyadic Analysis of Difference in Confidence in IOs in Germany

Note: OLS regression using Difference in IO confidence as a dependent variable (higher values indicate greater elite confidence in IOs relative to the citizen in the dyad). Entries are unstandardized coefficients with robust standard errors in parentheses, clustered at the level of citizens and elites. Significance levels: *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

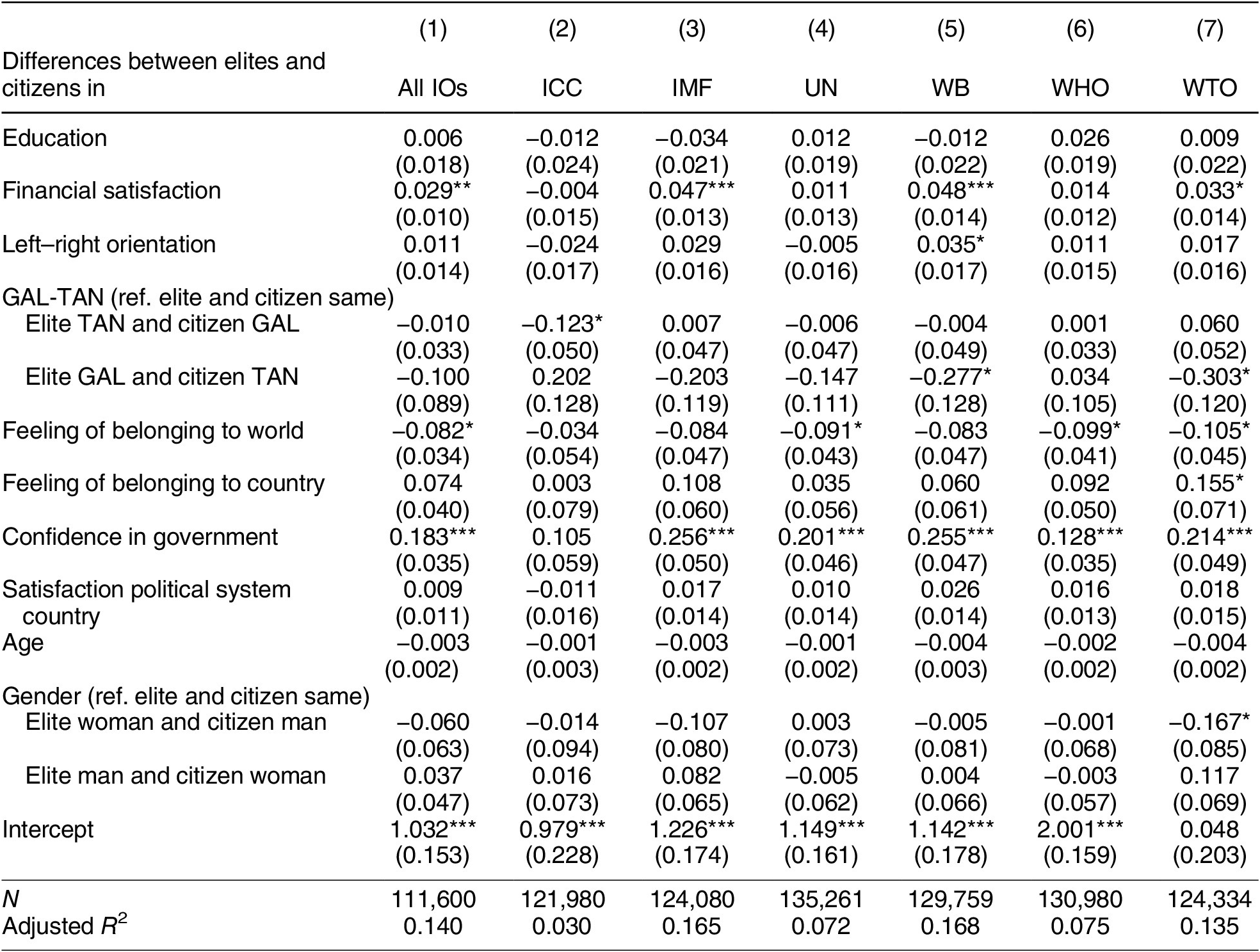

Table 4. Dyadic Analysis of Difference in Confidence in IOs in the Philippines

Note: OLS regression using Difference in IO confidence as a dependent variable (higher values indicate greater elite confidence in IOs relative to the citizen in the dyad). Entries are unstandardized coefficients with robust standard errors in parentheses, clustered at the level of citizens and elites. Significance levels: *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Table 5. Dyadic Analysis of Difference in Confidence in IOs in Russia

Note: OLS regression using Difference in IO confidence as a dependent variable (higher values indicate greater elite confidence in IOs relative to the citizen in the dyad). Entries are unstandardized coefficients with robust standard errors in parentheses, clustered at the level of citizens and elites. Significance levels: *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

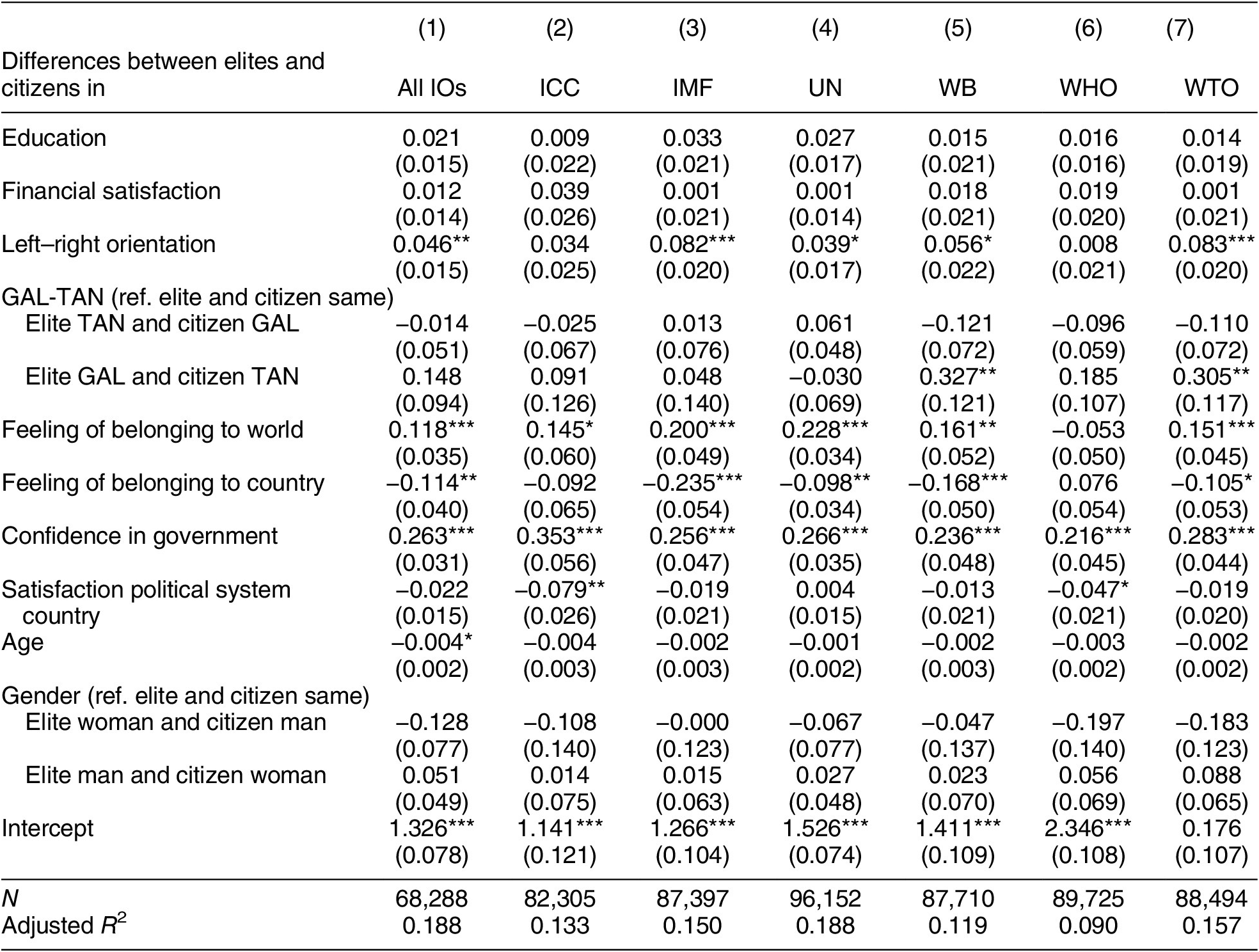

Table 6. Dyadic Analysis of Difference in Confidence in IOs in the US

Note: OLS regression using Difference in IO confidence as a dependent variable (higher values indicate greater elite confidence in IOs relative to the citizen in the dyad). Entries are unstandardized coefficients with robust standard errors in parentheses, clustered at the level of citizens and elites. Significance levels: *p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001.

Model 1 in Table 1 pools all countries and IOs. It shows statistically significant associations in the expected direction for six of the eight indicators. The exceptions are elite–citizen differences regarding feelings of national belonging and satisfaction with the political system. However, when replicating the analysis but excluding confidence in government, which is moderately correlated (r = 0.431, p = 0.000) with satisfaction with the political system, we observe a statistically significant and positive relationship for this indicator as well (Appendix Table E19).Footnote 6 Thus, these aggregate results support all four hypotheses and provide a compelling case for individual-level explanations of the elite–citizen gap in legitimacy beliefs toward IOs.

The picture is quite similar when we consider the results for each IO individually (Models 2–7 in Table 1). Confidence in government and both indicators for socioeconomic status are statistically significant with signs in the expected direction for all six IOs. In addition, at least one of the indicators of political values is associated with the elite–citizen gap vis-à-vis each IO. With respect to geographical identification, elite–citizen differences in global attachment play a role for five of the six IOs, while national attachment is only significant for the UN.

Grouping the IOs by issue orientation provides some interesting insights. Notably, while differences in left–right positioning are, as expected, associated with elite–citizen legitimacy gaps toward human security IOs (ICC, UN, WHO), the same relationships do not appear toward economic IOs (IMF, WB, WTO). One might have expected left–right positioning to matter particularly for attitudes toward economic IOs, which are often contested on these lines. As we shall see, part of the explanation lies in the pooling of data from countries with varying results in this respect.

Turning to the findings by country (Tables 2–6), we find continued support for all four explanations, albeit with some variation across countries. Looking at the pooled IO analysis for each country (Model 1 in Tables 2–6), we find evidence in all countries but the US for a positive and statistically significant association between elite–citizen differences regarding confidence in government and legitimacy gaps, bolstering the domestic institutional trust explanation. Likewise, socioeconomic status indicators are statistically significant and positive in four of the five countries, the exception being Russia. Elite–citizen differences in geographical identification appear to matter as expected in Russia and the US, but not in Brazil, Germany, or the Philippines. Regarding political values, we find significant associations for both measures in the US, mixed evidence in Brazil (GAL-TAN) and Russia (left–right), and no significant relationships in Germany and the Philippines.

While the main patterns remain, we observe further nuances when examining the results for specific IOs within specific countries (Models 2–7 in Tables 2–6). Elite–citizen differences regarding confidence in government are nearly always positively associated with gaps in legitimacy beliefs. The rare exceptions are the ICC in the Philippines and three IOs in the US (ICC, WB, WTO). The US partial exception may relate to the contextual circumstance that, with a more polarized political climate, trust in national government is less about an elite–citizen divide and more a function of which party is in control at the given time (Keele Reference Keele2007). A bivariate analysis indicates the absence of a relationship between confidence in government and IO legitimacy beliefs among both citizens and elites in the US.

Ways that socioeconomic status matters become clearer when examining particular IOs in particular countries. The results indicate that differences in education are positively associated with elite–citizen gaps in the US and for economic IOs in Germany, but not at all in Brazil, the Philippines, and Russia. The evidence further suggests that financial satisfaction matters broadly in the US, Brazil, and the Philippines, particularly in relation to economic IOs, but barely in Germany, and not at all in Russia. Taking the two indicators together, socioeconomic status is consistently related to elite–citizen gaps regarding IO legitimacy in the US, but it matters more ambiguously in Brazil, Germany, and the Philippines, and appears irrelevant in Russia. The evidence for socioeconomic status in the US ties in well with earlier research that supports this logic in this country (Scheve and Slaughter Reference Scheve and Slaughter2001). It is also apparent from this disaggregated analysis that socioeconomic status is of greater importance for elite–citizen gaps related to economic IOs than human-security IOs. This result may reflect distributional consequences from economic IOs that generally favor elites relative to citizens at large.

Political values appear to matter for elite–citizen legitimacy gaps toward IOs in all countries, but how they matter varies across settings. Elite–citizen differences in political values mainly matter as expected in the US, where both left–right and GAL-TAN orientations are associated with IO confidence in the anticipated direction. We also find some evidence consistent with our expectations in Germany, regarding left–right differences, and in Brazil and Russia, regarding GAL-TAN differences. By contrast, in Brazil, Germany, and the Philippines, elites who are more right-wing than citizens have more confidence in economic IOs. Likewise, GAL-TAN differences in the Philippines show effects in the opposite direction than expected. This variation in how political values matter may partly reflect party positioning in the respective countries. For example, in the US, the Democrats clearly embrace international cooperation more than the Republicans, while in Germany, the main dividing line runs between parties at the center of the political spectrum and parties at the extremes (Volkens et al. Reference Volkens2020). Thus, country context apparently shapes the effects of political values on IO legitimacy beliefs.

Finally, differences in geographical identification are associated with elite–citizen legitimacy gaps in Russia and the US. In these two countries, elites who feel a greater belonging to the world than citizens tend to accord more legitimacy to IOs. However, in Brazil and Germany, few IOs show the expected relationship. In the Philippines, we observe either no association or a negative association. National identification yields similar results. Only in Russia are elites with a stronger national attachment than citizens found to have less confidence in IOs, as theoretically expected. This result might reflect the particular sensitivity of Russian elites to perceived threats and lack of respect from “Western-dominated” IOs (White Reference White2007).

In sum, these findings suggest two broad conclusions. First, differences in individual-level factors systematically relate to elite–citizen gaps in legitimacy beliefs toward IOs. We find corroborating evidence for all four explanations in both pooled and disaggregated analyses. Second, the general explanatory patterns become more nuanced when we examine specific IOs and countries. These subtleties suggest that circumstances at the organizational and societal levels shape the role that individual-level drivers play in a particular context.

Robustness Checks

We conduct a number of additional analyses, which together support the robustness of the results. First, we replicate Tables 1–6 by including an indicator for differences in social trust (Appendix B), as several studies suggest that this factor may influence IO legitimacy beliefs (Dellmuth and Tallberg Reference Dellmuth and Tallberg2020; Harteveld, van der Meer, and De Vries Reference Harteveld, van der Meer and De Vries2013). Our results remain robust throughout. In Russia, the US, and to some extent Germany, social trust contributes to explaining the gap in legitimacy beliefs, as more trusting elites also hold more positive legitimacy beliefs toward IOs relative to citizens (Appendix Tables E1–E6).

Second, we control for differences in political knowledge, as such disparities may matter for the elite–citizen gap in IO confidence. Three items measure knowledge regarding global governance (Appendix B). About 62% of the elites correctly answered all three questions, as compared with about 20% for citizens. The main results remain robust, and the indicator for differences in knowledge is hardly ever significant (Appendix Tables E7–E12).

Third, we rerun the analyses without the variable regarding difference in satisfaction with the political system in one’s country, as this indicator is moderately correlated with difference in confidence in government (Appendix C), which may affect the estimates. All results remain robust, including those for the confidence in government indicator (Appendix Tables E13–E18). Conversely, we rerun the analyses without the variable confidence in government, keeping satisfaction with the political system. Our results remain robust, with the adjustment that the political satisfaction variable—which tends to be insignificant in the main regression tables—becomes significant in Brazil, Germany, the Philippines, and in the pooled model (Appendix Tables E19–E24). This additional check provides further support for Hypothesis 4.

Fourth, we redo the analyses leaving out differences in the feeling of belonging to one’s country, given its moderate correlation with global identification (r = 0.408; p = 0.000), potentially leading to a conflation of estimates. Again, our main results are robust (Appendix Tables E25–E30). However, the results for global identification turn insignificant in the pooled analysis and the Philippines (Tables E25 and E28), indicating that they are not robust to the exclusion of national identification.

Fifth, we run OLS regression analyses of elite confidence and citizen confidence separately, as discussed earlier under modeling specification (Appendix Tables E31–E42). We include the same variables as in the dyadic analyses. Although this approach does not examine sources of elite–citizen legitimacy gaps as directly as dyadic analyses, the conclusions from the OLS regression analyses are largely consistent with those from the dyadic analyses.

Finally, we control for variation by elite types by adding them as dummy variables in the models, using political party elites as the reference category (Appendix Tables E43–E48). Removing variation for specific elite types by adding these dummies does not change our main results. The elite types themselves have varying effects in different countries.

Conclusion

Is there a gap between elite and citizen legitimacy beliefs toward IOs, and if so what might explain it? While academic and public debates offer many claims about elite–citizen divergences regarding global governance, systematic evidence and analyses are in short supply. This article has offered an unprecedented comparative analysis of this issue. Our ambition has been threefold. First, using novel data from two uniquely coordinated international surveys, we have assessed the existence of an elite–citizen gap in legitimacy beliefs toward IOs. Second, theoretically, we have developed an individual-level approach to explaining such gaps, building on the proposition that elites and citizens differ systematically in a set of characteristics that shape legitimacy beliefs. Third, empirically, we have undertaken a dyadic analysis of elite–citizen gaps in legitimacy beliefs toward IOs.

Our study yields two central findings. First, on average elites do indeed tend to consider IOs more legitimate than citizens at large, confirming the existence of an elite–citizen gap. This pattern holds for all six IOs, four of five countries, and all six elite types examined. Second, this legitimacy gap is widely associated with differences between elites and citizens in terms of our four privileged individual-level characteristics: socioeconomic status, political values, geographical identification, and domestic institutional trust. At the same time, the relative importance of these drivers varies across IOs and countries, reflecting contextual circumstances.

While these findings derive from unparalleled comparative data, we should also note the study’s limitations and how future research might address them. For one thing, the two surveys offer a snapshot of IO legitimacy beliefs at a particular point in time, and only future research can assess whether these findings reflect time-specific conditions. Furthermore, future research could assess the generalizability of these findings by extending the study to more countries and IOs. Finally, future research could explore other potential drivers of elite–citizen gaps in IO legitimacy, located either at the individual level or at the organizational and societal levels.

Yet, for now, our findings carry four broader implications. First, they suggest that global governance may confront problems of democratic accountability. The democratic credibility of a political system can partly be judged by the closeness of opinion between those who govern and those who are governed (Achen Reference Achen1978; Pitkin Reference Pitkin1967). While such opinion congruence has been extensively studied in comparative politics, it has received less attention in global governance research (for an exception, see Schneider Reference Schneider2019). Our findings indicate that elites, who conduct the global governing, consistently accord more legitimacy to IOs than citizens at large. Whether such gaps result in practical problems of democratic accountability depends on whether elites adjust their policy positions to meet citizen views.

Second, our findings highlight a significant challenge for contemporary international cooperation. A large literature suggests that intergovernmental collaboration is somewhat hostage to domestic support (Martin Reference Martin2000; Putnam Reference Putnam1988). If domestic constituencies back international cooperation, state leaders can more readily pursue ambitious international policies, secure treaty ratifications, and implement new international rules. Yet our results show that citizens are generally more skeptical of IOs than elites, raising questions about the viability of elite-driven international cooperation.

Third, and relatedly, our findings clarify why populist politicians around the world take advantage by targeting IOs with antiglobalist messages. Research highlights how the success of populist parties is dependent on a demand for their positions, rooted in economic and cultural change in societies, as well as a supply of these positions by populist entrepreneurs spotting the potential (De Vries, Hobolt, and Walter Reference De Vries, Hobolt and Walter2021; Inglehart and Norris Reference Inglehart and Norris2017). Our findings suggest why populist politicians find it profitable to target IOs controlled by “out of touch” elites. In addition, our results show how this potential is grounded in differences between elites and citizens across a broad range of factors. Those who want to turn the populist tide need to recognize and reduce these differences.

Finally, our findings suggest that research on attitudes toward international cooperation would do well to explore complementary explanations through comparative designs. Existing scholarship often debates whether opinions on international affairs are driven mainly by economic or other concerns (Hainmueller and Hiscox Reference Hainmueller and Hiscox2006; Hobolt and De Vries Reference De Vries2018; Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2005; Scheve and Slaughter Reference Scheve and Slaughter2001). In contrast, our findings indicate that the elite–citizen gap in IO legitimacy beliefs arises from a combination of drivers, pushing us to explore theoretical complementarities rather than rivalries. In addition, by showing how the relative strength of these explanations partly varies by IO and country, our results underline the importance of comparative designs, in order to avoid context-bound and oversimplified conclusions.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421000824.

Data Availability Statement

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the American Political Science Review Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/NDHWX0. The included data are provided for replication purposes only. Please contact the authors for further information about the full release of the data.

Acknowledgments

Earlier versions of this article have been presented at the Annual Convention of the ISA in Toronto in 2019; the Joint Sessions of the ECPR in Mons in 2019; the Annual Meeting of the APSA in Washington DC in 2019; and at workshops organized by GIGA Hamburg, Maastricht University, Stockholm University, Södertörn University College, University of Duisburg-Essen, University of Edinburgh, University of Toronto, Yale University, and the iCourts and LegGov research programs. For thoughtful comments and suggestions, we thank Karen Alter, Sarah Bush, Mark Copelovitch, Joost de Moor, Farsan Ghassim, Catherine Hecht, Hortense Jongen, Christoph Mikulaschek, Christina Schneider, Ken Scheve, Bernd Schlipphak, Theresa Squatrito, Carl Vikberg, and Erik Voeten, as well as additional participants at these conferences and workshops. In addition, we are indebted to the editors and three reviewers for APSR for very valuable advice and to our partner country teams in Brazil, Russia, South Africa, and the US for making the LegGov Elite Survey possible. This article is based on collaborative research within the LegGov research program. The alphabetical author ordering reflects equal contributions to this article.

Funding Statement

This research was funded by Riksbankens Jubileumsfond (Grant M15-0048:1). In addition, Lisa Dellmuth received funding from the Swedish Research Council (Reference Dellmuth and Tallberg2015-00948) and Soetkin Verhaegen from F.R.S.-FNRS postdoctoral fellowship 1.B.421.19F.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

Ethical Standards

The authors declare that the human subjects research in this article was conducted in accordance with the principles and guidelines of Stockholm University and the Swedish Ethical Review Authority. For further information, see Appendix F in the Supplementary Material. The authors affirm that this article adheres to the APSA’s Principles and Guidance on Human Subject Research.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.