No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 April 2017

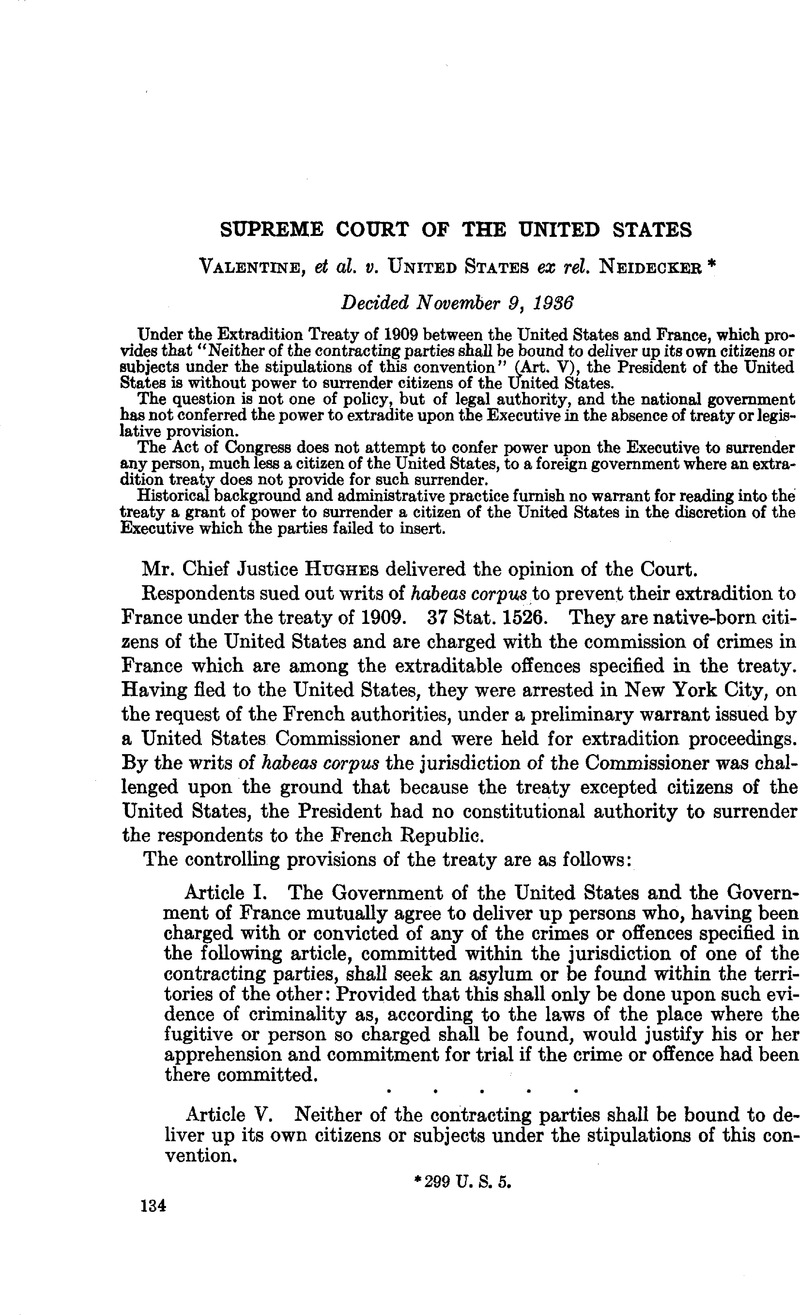

U. S. 5

1 Moore, , Int. Law Dig., Vol. IV, sec. 594; Moore on Extradition, Vol. I, pp. 159–162.Google Scholar

2 Great Britain, 1794, Art. XXVII, 1 Malloy, Treaties, p. 605; 1842, Art. X, id., p. 655;1889, id., p. 740; 1931, 47 Stat. 2122; France, 1843,1 Malloy, p. 526; Italy, 1868, id., p. 966.See, also, Switzerland, 1850, Art. XIII, 2 Malloy, p. 1767; Venezuela, 1860, Art. XXVII, 2 Malloy, p. 1854; Dominican Republic, 1867, Art. XXVII, 1 Malloy, p. 413; Nicaragua, 1870,2 Malloy, p. 1287; Orange Free State,1871, Article VIII, 2 Malloy, p. 1312; Ecuador, 1872, 1 Malloy, p. 436.

3 Quoted in Moore on Extradition, Vol. I, pp.22, 23; Moore, , Int. Law Dig., Vol. IV, p. 246.Google Scholar

4 Moore on Extradition, Vol. I, p. 21.

5 Moore on Extradition, Vol. I, p. 50.

6 1 Malloy, 1027. Quoted in Charlton v. Kelly, 229 TJ. S. 447, 467.

7 The provision of the treaty with the Argentine Republic, 1896, Art. 3,1 Malloy, 26, is as follows:

“In no case shall the nationality of the person accused be an impediment to his extradition,under the conditions stipulated by the present treaty, but neither Government shall be bound to deliver its own citizens for extradition under this convention; but either shall have the power to deliver them up, if in its discretion it be deemed proper to do so.” The same phraseology is used in the treaty with the Orange Free State,1896, Art. V, 2 Malloy, 1316.

8 1 Malloy, 1186. The treaties with Guatemala, 1903, Art. V, 1 Malloy, 881, and with Nicaragua, 1905, 2 Malloy, 1295, have the same provision.

The treaty with Uruguay, 1905, Art. X, 2 Malloy, 1828, provides: “The obligation to grant extradition shall not in any case extend to the citizens of the two parties, but the executive authority of each shall have power to deliver them up, if, in its discretion, it is deemed proper to do so.”

9 2 Malloy, 1503.

10 1 Malloy, 1127.

11 Moore on Extradition, Vol. I, pp. 164–167; Moore, , Int. Law Dig., Vol. IV, pp. 301–303.Google Scholar

12 Mr. Frelinghuysen’s views appear in a report to the Senate. Sen. Ex. Doc. 98, 48th Cong., 1st sess. See Moore on Extradition, Vol. I, pp. 167, 168. Discussing the constitutional powers of the President, Mr. Frelinghuysen concluded:

“Thus it appears that, by the opinions of several Attorneys–General, by the decisions of our courts, and by the rulings of the Department of State, the President has not, independent of treaty provision, the power of extraditing an American citizen; and the only question to be considered is whether the treaty with Mexico confers that power.

“By the treaty with Mexico proclaimed June 20, 1862, this country places itself under obligations to Mexico to surrender to justice persons accused of enumerated crimes committed within the jurisdiction of Mexico who shall be found within the territory of the United States; and further provides that that obligation shall not extend to the surrender of American citizens. The treaty confers upon the President no affirmative power tosurrender an American citizen. The treaty between the United States and Mexico creates an obligation on the part of the respective governments, and does no more, and where the obligation ceases the power falls. It is true that treaties are the laws of the land, but a statute and a treaty are subject to different modes of construction. If a statute by the first section should say, The President of the United States shall surrender to any friendly power any person who has committed a crime against the laws of that power, but shall not be bound so to surrender American citizens, it might be argued, perhaps correctly, that the President had a discretion whether he would or would not surrender an American citizen. But a treaty is a contract,and must be so construed. It confers upon the President only the power to perform that contract. I understand the treaty with Mexico as readingthus: The President shall be bound to surrender any person guilty of crime, unless such person is a citizen of the United States.

0201C;Such being the construction of the treaty, and believing that the time to prevent a violation of the law of extradition was before the citizens left the jurisdiction of the United States,I telegraphed the Governor of Texas that an American citizen could not legally be held under the treaty for extradition.

0201C;It would be a great evil that those guilty of high crime, whether American citizens or not,should go unpunished; but even that result oould not justify an usurpation of power.”

13 Moore on Extradition, Vol. I, p. 167.

14 See note 7.

15 See note 8.

16 Moore, Int. Law Dig., Vol. IV, p. 298.

17 Documents Parlementaires (1909), Chambre des Deputes, Annexe $391; id., Sinai, Annexe 2338.