In their article Imperfect Alternatives: Institutional Choice and Reform of Investment Law, Sergio Puig and Gregory Shaffer develop a clear and discerning comparative framework to evaluate alternatives to the current system of investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS).Footnote 1 In her essay Incremental, Systemic, and Paradigmatic Reform of Investor-State Arbitration, Anthea Roberts offers us a bracingly candid typology to describe the various actors involved in the recent efforts toward reform.Footnote 2 My essay is meant to complement these excellent contributions and to focus unflinchingly on the tripartite role of the state itself. What I call the ISDS Trinity can be understood as shorthand for the state's systemic role as (1) law-giver, (2) protector of investment, and (3) respondent. Looking at current and future design trade-offs, I suggest that whether an institutional choice is embraced within the ISDS system has a lot to do with how well the reform validates each of these three roles. In this way, the ISDS Trinity offers further insight into how each state will approach the various trade-offs and intercamp dynamics described by Puig and Shaffer, and by Roberts, within the current debate. Put another way, the ISDS Trinity sheds additional light on whether a reform to the system will be well-received by a state and thus enjoy a greater chance of adoption.

ISDS Reform and the Centrality of the State

With the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) Working Group III's “government-led” reform process underway,Footnote 3 and with significant revisions to the International Centre for the Settlement of Investment Disputes arbitration rules already in draft,Footnote 4 we are in a time of profound change within the ISDS system. Gone are the more palliative descriptions of the system as one experiencing “growing pains,”Footnote 5 and instead a far more existential rhetoric fills the current debates.Footnote 6 Whether we are in a time of productive reform and evolution remains to be seen. Evolution does not necessarily result in survival.

In this context, the role of the state looms large.Footnote 7 The state as institutional designer—whether incremental, systemic, or paradigmatic in its approach to the current debates—will ultimately decide whether the current system of international adjudication will persist and on what terms. States are the dynamic actors in the process of reform. They are all at once the reactionaries and the revolutionaries within the ISDS system. In addition, the role of the state is always primary and always essential at the early design stages of a procedural innovation. Thus, states have unique and leading roles within the ISDS system.

Explanation of the ISDS Trinity

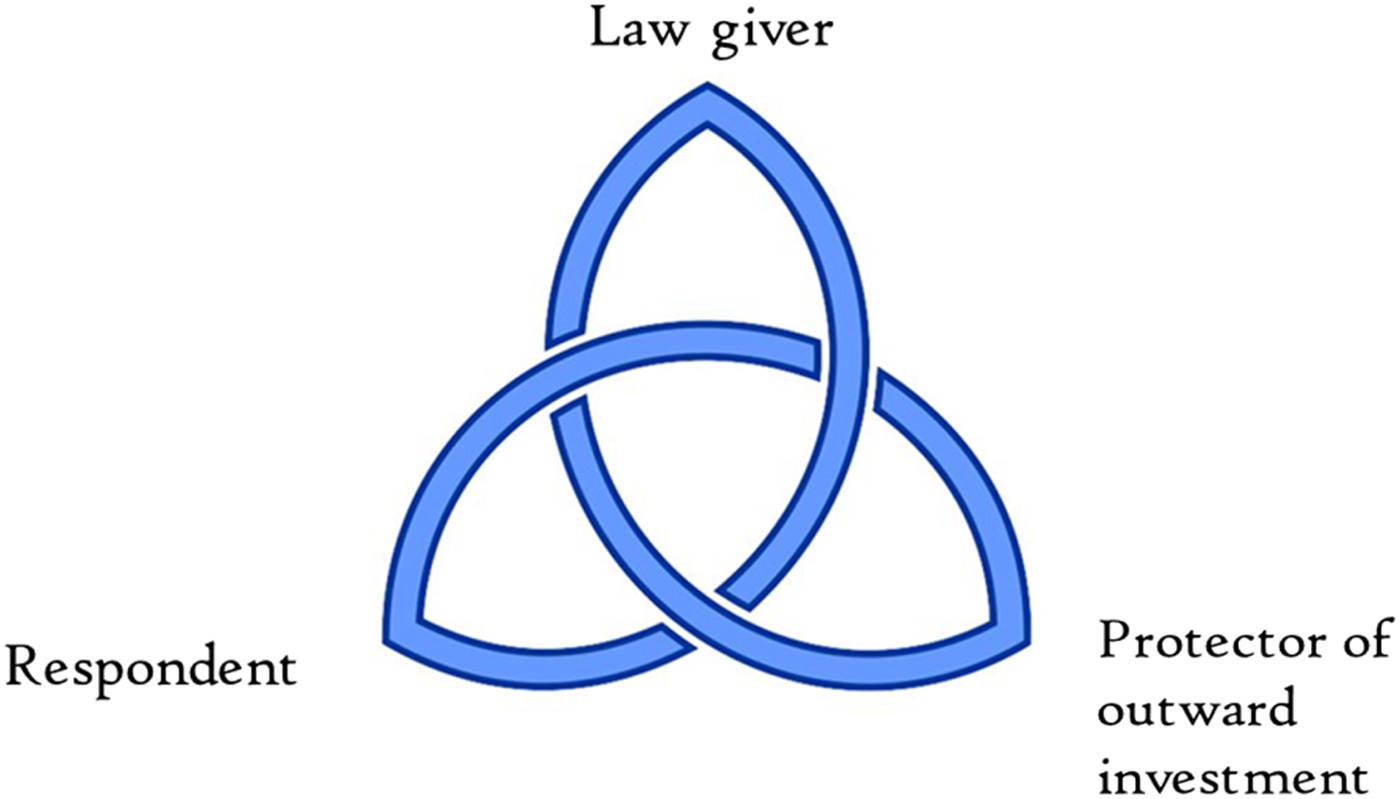

In particular, states occupy three distinct yet interconnected roles—what I call the ISDS Trinity. First, they are the law-givers through their treaty and rule-making function. Second, they are the protectors of outward investment in that they establish transnational obligations and depoliticized systems for efficient adjudication of disputes for investors who seek to invest capital abroad. And third, they are respondents through their offers to arbitrate in international investment agreements and subsequent participation in the arbitral process. Each role has different attendant interests and thus each state necessarily calibrates the emphasis it puts on the three roles in its own parochial way based on its perceived needs. Moreover, states occupy the three roles at the same time. Even when a state is not a respondent in an active investment arbitration, it is nonetheless aware of its role as a potential respondent. Similarly, even if a state is not the recipient of large amounts of foreign direct investment, it is nonetheless aware of the interests associated with the promotion of investment abroad. Thus, while every state must take account of each role within the ISDS Trinity, no state is likely to approach its role identically to any other. A visual depiction of the ISDS Trinity in perfect balance might look like this:

For any given state, the ISDS Trinity is dynamic and typically unbalanced. Indeed, a state's posture within the ISDS Trinity shifts internally depending on the dominant role it is playing within the ISDS system. A state may privilege certain interests when it is sitting as a law-giver. For example, at the negotiating table of an international investment agreement or within the plenary of the UNCITRAL Working Group III meeting, a state may prioritize international norms, state-to-state cooperation, and diplomacy.Footnote 8 The state may consider other interests of primary importance when it is a respondent in an active investment arbitration. For example, a state may be most concerned with vindicating interests of sovereignty or cost-efficient proceedings in this role. Similarly, respondent interests may be more important to the state when sitting as law-giver if the state is traditionally a capital-importing state with an emerging regulatory apparatus to handle investment. A state may, on the other hand, privilege strong investment protection ideals if it has yet to face a claim and has a strong economy of outward-bound investment.

These variations in emphasis do not necessarily mean that the state is acting solely in its own self-interest or without care to its other roles within the system (i.e., the other points of the Trinity). Nor are a state's interests mutually exclusive. The state must understand the interests underpinning each of the roles it plays within the ISDS Trinity at every systemic decision-point. When law-giver, it must be mindful of its role as respondent and protector. When respondent, it must be mindful of its role as law-giver and protector. To take some liberty and extend the framework put forward by Puig and Shaffer, “these decision-making processes are biased in different ways because of the dynamics of participation within them” and “any meaningful public policy analysis must involve comparative institutional analysis of real-world (rather than ideal) alternatives.”Footnote 9 In other words, states are weighing and comparing their tripartite institutional roles within the system at every moment.

By way of example, here is a nonexhaustive list of the kinds of interests that dominate each attendant role within the ISDS Trinity:

We can apply the ISDS Trinity to any number of moments when a state must decide upon a course of action within the investor-state dispute system. When the reform being proposed is well-balanced within the Trinity, there is a greater likelihood that the reform will proliferate rapidly and become successful. As Puig and Shaffer remind us, “Contexts differ across States, and choices should depend on those contexts.”Footnote 10 The ISDS Trinity provides insight into the roles attendant to a state within the system and into how a state may understand the contingent contexts for any given decision. Mapped onto the question of reform, the ISDS Trinity placed in “context” can help us to anticipate how a state may react when “facing different challenges to select from a menu of imperfect international alternatives in light of their trade-offs.”Footnote 11 In other words, when a reform proposal is supportive of each of the state's roles within the ISDS Trinity, a state will have an easier time accepting it and ensuring its proliferation.

Nevertheless, one need not refer to the tripartite role of the state only in the context of ISDS reform debates. Indeed, one could also apply the ISDS Trinity to any number of questions when a state must engage with the ISDS system, including how a state may approach a non-disputing-party submission, negotiate an obligation within an investment treaty, or approach a settlement negotiation. In this way, the Trinity is generally useful as a heuristic by which to ascertain and evaluate state positions.

Example of the ISDS Trinity in Practice

The availability of third-party submissions in an investment arbitration helps to illustrate the ISDS Trinity in practice.Footnote 12 The number of third-party submissions has grown steadily since 2001.Footnote 13 These submissions are now nearly universally possible, as institutions, states, arbitrators, and most practitioners have accepted the concept of third-party submissions with exceptional speed.

Third-party submissions did not evolve gradually—they burst onto the scene and found a home within the system almost immediately. In August 2000, a third party for the first time requested permission to participate in an investor-state arbitration as an amicus curiae—the International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) asked the Methanex Corporation v. United States of America North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) Chapter 11 tribunal for “permission to submit an Amicus Curiae brief to the Tribunal on critical legal issues of public concern in the arbitration.”Footnote 14 The application was concise, spare, and persuasive. In explaining why they should be permitted to file, the petitioners anticipated many of the substantive criteria that would later govern third-party motions, noting that “[t]he legal issues raised in this case are of immense public importance,” that the ruling “will have a critical practical impact on environmental and other public welfare law-making at the federal, state and provincial levels throughout the NAFTA region,” and that the subjects under consideration “are matters of public interest distinct from the commercial issues that arbitration processes normally handle.”Footnote 15

The various submissions of the NAFTA parties in response to IISD's request suggest that third-party submissions are manifestly consistent with the idea that the state holds the tripartite role of law-giver, respondent, and protector.Footnote 16 All three NAFTA parties submitted views: the United States (in this case in its express role as a disputing party) in October 2000,Footnote 17 and both Mexico and Canada (as nondisputing parties pursuant to a request by the tribunal and the express authority granted by NAFTA Article 1128) in November 2000.Footnote 18

Consider how those views illustrate the ISDS Trinity: The United States did not simply approach the question of the propriety of a third-party motion as a respondent. It understood that it was the respondent but also kept its systemic roles as “law-giver” and “protector of investment” at the fore by noting that ISDS is of a “fundamentally different nature than a typical international commercial dispute” and that the Tribunal's decision on the merits “may have a significant effect beyond the two parties to the dispute.”Footnote 19 Mexico, too, sought to balance its role within the context of the ISDS Trinity and raised concerns regarding the integrity of both its own legal system and its obligations under a multinational agreement—echoing the Puig and Shaffer framework that a state will act in response to differences in “capital endowment, market size, ideology, institutional development, and historical legacy.”Footnote 20 Mexico pointed out that third-party participation is not provided for in civil law jurisdictions, that the tribunal must be sensitive to the fact that NAFTA's investor-state dispute system draws “a careful balance between the procedures of common law countries and those of civil law countries (such as Mexico),” and that the “fact that a specific procedure or legal concept may exist in a Party's domestic law cannot serve as grounds to transport it into the international plane.”Footnote 21 Finally, Canada recognized the “importance of ensuring uniformity and predictability in the rules and procedures governing the settlement of investment-state disputes,” noted that there “are numerous complex legal and technical issues raised by the question of whether and how a NAFTA Chapter Eleven tribunal should receive submissions from persons other than the disputing Parties or the non-disputing NAFTA Parties,” and therefore implored the “NAFTA partners to work together on the issue of amicus curiae participation as a matter of urgency in order to provide guidance to Chapter Eleven tribunals.”Footnote 22 The debate among the three NAFTA parties ultimately resulted in a compromise consensus position. Sitting as the authoritative Free Trade Commission (FTC),Footnote 23 the NAFTA parties issued an official statement favoring the availability of third-party participation.Footnote 24

Much can be written on this debate, how tribunals who looked at this question prior to the FTC interpretation helped move the narrative, and the shifting rhetoric employed by each state as it sought to balance itself within the ISDS Trinity. Nevertheless, if one looks at the debate in detail one can see that the NAFTA parties found comfort in the fact that the divergent and sometimes conflicting interests reflected in the Trinity were in sufficient balance. The United States, Canada, and Mexico each approached the question whether to support admission of third-party submissions first within their immediate context (as protector, respondent, and law-giver), then with reference to the different nondominant roles within the ISDS Trinity, and finally as custodians of the system in the posture of reformer. Each submission struggled to place procedural innovation in the appropriate context and balance with the various roles of the state. In other words, the decision to allow third-party submissions adequately promoted each of the competing interests of the ISDS Trinity—even when those interests did not necessarily support the state's immediate role as respondent or protector of an investor.

Conclusion

We are now in a time of rising populism and resurgent nationalism. The question of ISDS reform echoes within a larger conversation regarding global trade and investment. The extent to which states understand investment arbitration as a transnational and cosmopolitan good will vary, and this fact is likely to further complicate the debate currently underway at the UNCITRAL Working Group III meetings and elsewhere in international investment agreement negotiations. However, in grappling with these particular challenges, states that participate in the ISDS system are likely to test the various proposed innovations in the years to come against the crucible of their roles within the ISDS Trinity.

Target article

Imperfect Alternatives: Institutional Choice and the Reform of Investment Law

Related commentaries (7)

A Trinity Analytical Framework for ISDS Reform

Control, Capacity, and Legitimacy in Investment Treaty Arbitration

Introduction to the Symposium on Sergio Puig and Gregory Shaffer, “Imperfect Alternatives: Institutional Choice and the Reform of Investment Law,” and Anthea Roberts, “Incremental, Systemic, and Paradigmatic Reform of Investor-State Arbitration”

The Global Laboratory of Investment Law Reform Alternatives

The Limitations of Comparative Institutional Analysis

The Role of the State and the ISDS Trinity

Who's Afraid of Reform? Beware the Risk of Fragmentation