No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 12 April 2017

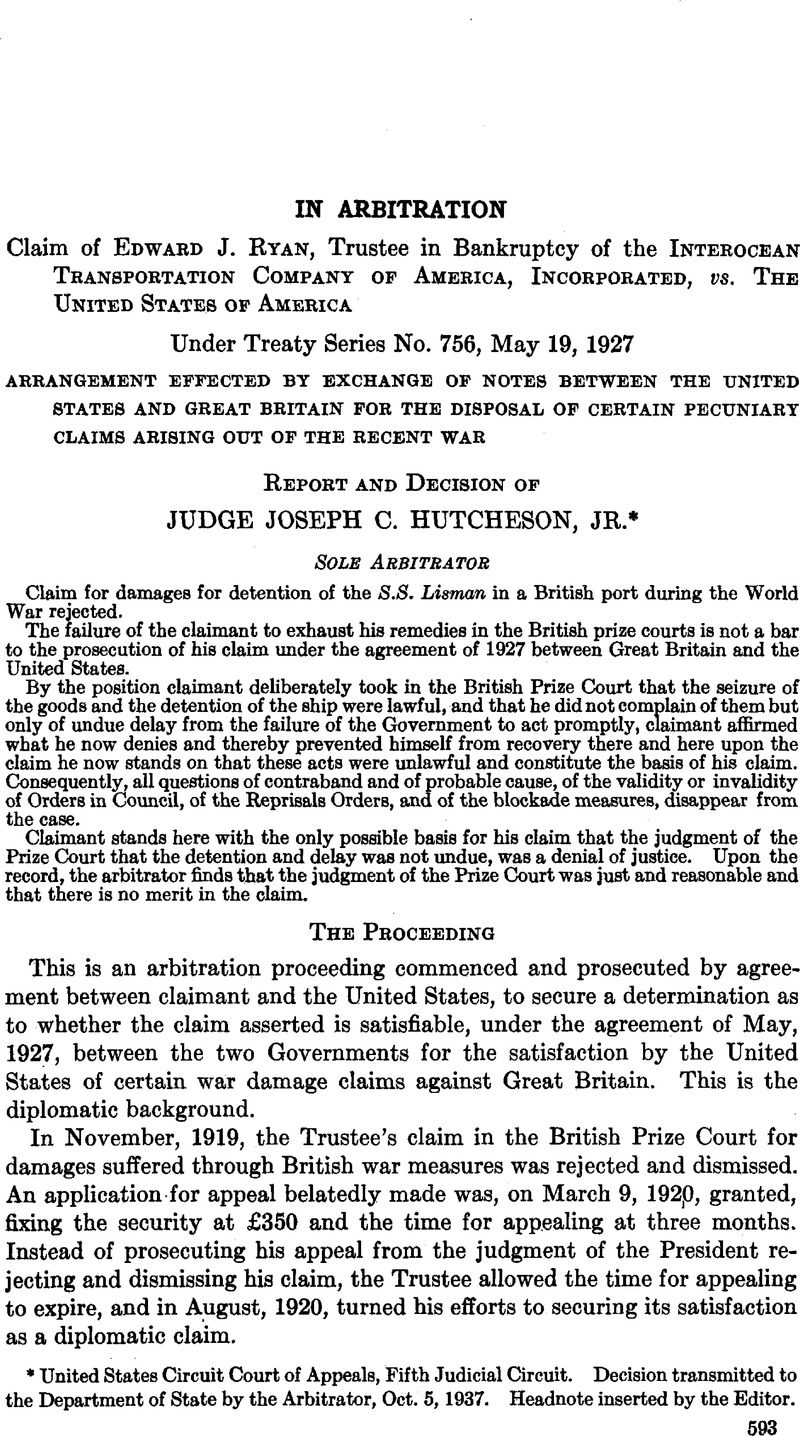

* United States Circuit Court of Appeals, Fifth Judicial Circuit. Decision transmitted to the Department of State by the Arbitrator, Oct. 5, 1937. Headnote inserted by the Editor.

1 The Paquete Habana, 175 U. S. 677; Moore, Int. Law Digest, Sec. 1069; “‘Arbitration’ as a Term of International Law,” T. W. Balch, 15 Columbia Law Review, p. 590; Private Law Sources, and Analogies of International Law, Lauterpacht, Chap. 3, pp. 60–71.

2 In such instances, the claim presented, the obligation adjudicated, is in legal cognizance not a governmental, but an individual claim; the amount claimed is owed not to a government but to the individual claiming.

3 Claims of this kind, though they take their substance from, and are concreted in, particular injuries to individuals, are in legal cognizance not individual, but national claims, the amounts claimed are owed by the government claimed against not to individuals, but to the government claiming.

4 On April 27, 1915, it was duly registered with Charles Smith as master, and the Philadelphia Trust Deposit and Insurance Company Trustee, as owner. The Shawmut Company was, however, in 1915 in control of the Lisman and its sister ships, and was, in fact, the real owner. The significance of the registry in the name of the Philadelphia Trust Safe Deposit and Insurance Company is that this company was on the list of banks and banking agencies which were remitting to enemy countries, and the point is made that this registry made the ownership and control of the Lasman sufficiently obscure to be a matter of concern to the British Government at the time the vessel cleared from New York.

5 Foreign Relations, Supp., 1915, pp. 269–270–271, 273; Claimant’s Memorial, p. 46; Foreign Relations, Supp., 1914, pp. 269–270, 1915, p. 138.

6 Claimant’s Annex, p. 123.

7 Claimant’s Memorial, p. 69, its Annex, 42; cf. The Seaconnet, Lloyd’s List Law Reports, Vol. 2, p. 260.

8 The claim in the Prize Court on account of this detention as reported in Lloyd’s List Law Reports, Vol. 2, p. 260, was a claim for $3,700 a day for 27 days undue detention. It appeared that 900 tons of the cargo discharged at North Shields were, upon the admission of counsel for claimants, contraband destined for Germany. It was found that there was no undue detention and the claim was dismissed with costs. The record does not show what finally became of the Seaconnet. It does show that on September 27, 1915, the Interocean Transportation Company, charterer of the Lisman and the Seaconnet, was adjudioated an involuntary bankrupt.

9 Cf. Pyke, Law of Contraband of War, Chap. XIII, p. 166; International Law and the Great War, Phillipson, Chap. XVIII, pp. 327–9; Neutrality, its History, Economics and Law, Vol. III, The World War Period, p. 8 (Columbia University Press).

10 It may be noted here that its adoption was opposed by Great Britain, that the proposal the United States made in August, 1914, that the Declaration be adopted, was not accepted, and that on October 22, 1914, the Government of the United States advised the British Government that it had withdrawn its suggestion that the Declaration of London be adopted as a temporary code of naval warfare, and that “this Government will insist that the rights and duties of the United States and its citizens in the present war be defined by the existing rules of international law, and the treaties of the United States, irrespective of the Declaration of London.” United States Foreign Relations, 1914, Supp., pp. 256–7–8.

11 Cf. Millis, Road to War—America, 1914–17, pp. 82–89.

12 Cf. Neutrality, Vol. I, The Origins, Chap. 6.

13 Neutrality, Vol. I, The Origins, Chap. 7.

14 Cf. Neutrality, Vol. II, The Napoleonic Period, Chap. II, Chap. XIV; Neutrality, Vol. IV, Today and Tomorrow, Chap. II; Seymour, American Diplomacy during the World War, p. 43.

15 “United States and the Rights of Neutrals, 1917–1918,” Am. Jour. Int. Law, January, 1937, Morrissey, Alice M.; United States Foreign Relations, 1917, Supp., p. 865 Google Scholar and note; Claimant’s Annex 155.

16 “Law as Liberator, p. 135 (Hutcheson, Foundation Press, Inc.); “The Judgment Intuitive,” C.L.Q. April, 1929.

17 “The Principles Underlying Contraband and Blockade,” Montmorency, Grotius Society, 1916, Vol. II (Sweet & Maxwell, Ltd.).

Neutrality, its History, Economics and Law, Vols. 1–2–3–4, Columbia University Press, 1936.

United States Neutrality Act 1935, as amended in 1936, and reënacted in 1937. The discussion of it by Garner, Am. Jour. Int. Law, July, 1937, p. 385; Proceedings of the Society of International Law, April 29 to May 1, 1937.

“Neutrality and Collective Security,” Harris Foundation Lectures, 1936. (University of Chicago Press.)

18 “Growth of Belligerent Rights over Neutral Trade,” Penn. Law Review, Vol. 68, pp. 20–49.

19 “Violations of Maritime Law by the Allied Powers during the World War,” Am. Jour. Int. Law, Vol. 24, p. 79.

20 Prize Law during the World War (Macmillan), p. 26.

21 Judicial Aspects of Foreign Relations, Harvard Studies in Administrative Law, Vol. 6.

22 “Neglected Fundamentals of Prize Law,” 30 Yale Law Rev., Vol. 3; “Prize Law and Modern Conditions,” Am. Jour. Int. Law, Vol. 25, p. 625.

23 International Law and some Current Illusions (Macmillan).

24 “The Kim Case,” Law Quar. Rev., Vol. 32, p. 50; The Law of Contraband of War (Oxford Press, 1915).

25 “Modern Developments of the Law of Prize,” Pa. Law Rev., Vol. 75, p. 505.

26 International Law and the Great War.

27 International Law chiefly as Interpreted and Applied by the United States.

28 International Law, Vol. II, Part 3, Neutrality.

29 “Retaliation and Neutral Rights, The Leonora,” Mich. Law Rev., Vol. 17, p. 564.

30 “International Law of War since the War,” Iowa Law Rev., Vol. 19, p. 165.

31 “Plurality or Unity of Juridical Orders,” Iowa Law Rev., Vol. 19, p. 245.

32 Cf. “British Prize Courts and International Law,” British Year Book of International Law, 1921, p. 21; “Development of German Prize Law,” Columbia Law Rev., Vol. 18, 503, at pp. 508–511.

33 4 Lloyd’s 1, App. Cases, Vol. II, p. 77.

34 App. Cases, 1919, p. 279.

35 App. Cases, 1919, p. 974.

36 Garner, Prize Law since the World War; Pake, , “The Law of the Prize Court,” Law Quarterly Rev., Vol. 32, p. 144 Google Scholar.

37 Cf. Tiverton, Prize Law (Butterworth & Co., 1914).

38 Mixed Claims Commission, Consolidated Edition of Decisions and Opinions, 1925–8 p. 33 el seq.

39 Neutrality, Vol. 2, The Napoleonic Period, particularly Part 2.