No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 04 May 2017

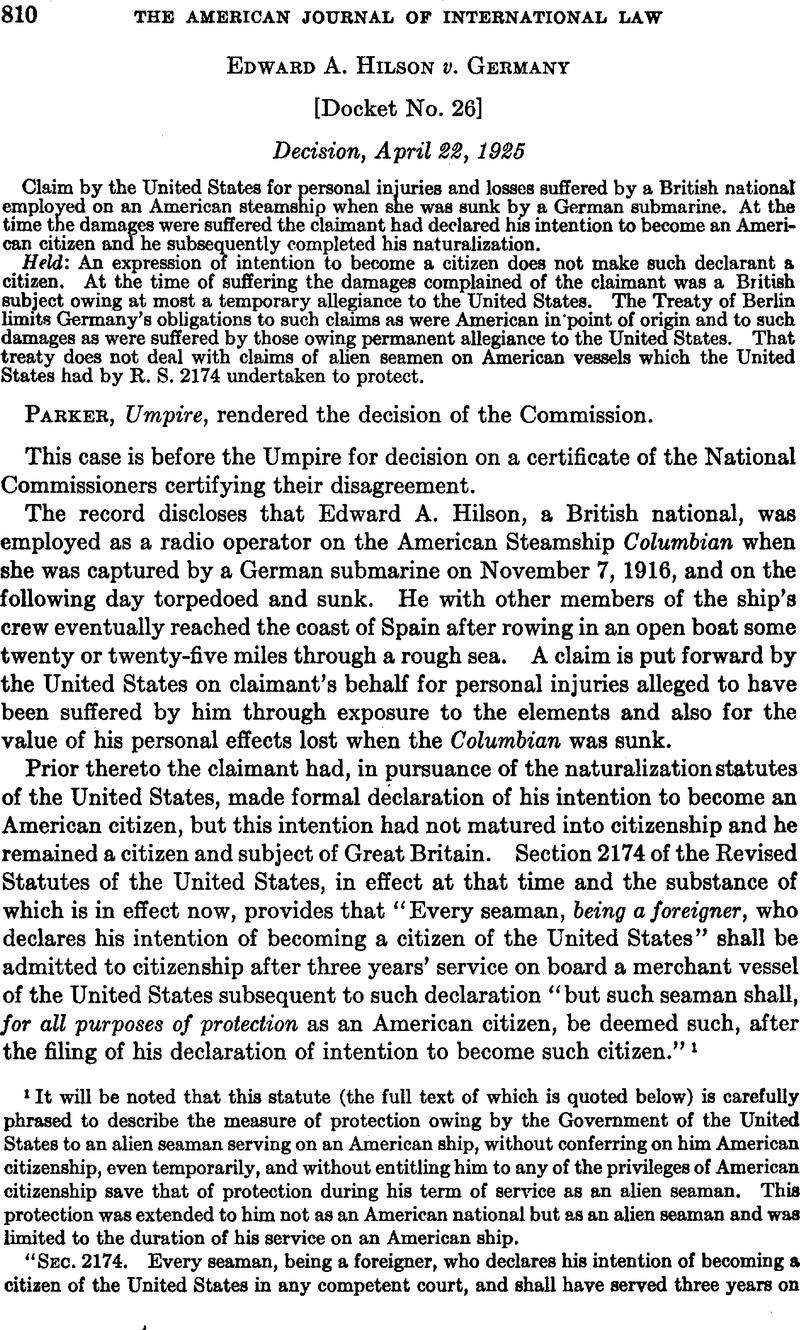

1 It will be noted that this statute (the full text of which is quoted below) is carefully phrased to describe the measure of protection owing by the Government of the United States to an alien seaman serving on an American ship, without conferring on him American citizenship, even temporarily, and without entitling him to any of the privileges of American citizenship save that of protection during his term of service as an alien seaman. This protection was extended to him not as an American national but as an alien seaman and was limited to the duration of his service on an American ship.

“SEC. 2174. Every seaman, being a foreigner, who declares his intention of becoming a citizen of the United States in any competent court, and shall have served three years on board of a merchant-vessel of the United States subsequent to the date of such declaration, may, on his application to any competent court, and the production of his certificate of discharge and good conduct during that time, together with the certificate of his declaration of intention to become a citizen, be admitted a citizen of the United States; and every seaman, being a foreigner, shall, after his declaration of intention to become a citizen of the United States, and after he shall have served such three years, be deemed a citizen of the United States for the purpose of manning and serving on board any merchant-vessel of the United States, anything to the contrary in any act of Congress notwithstanding; but such seaman shall, for all purposes of protection as an American citizen, be deemed such, after the filing of his declaration of intention to become such citizen.”

SEC. 2174 of the Revised Statutes was repealed by section 2 of the Naturalization Act approved May 9,1918, 40 Statutes at Large 542, after its provisions, with some modifications, had been incorporated in the 7th and 8th subdivisions in section 1 thereof, still in force.

2 See Administrative Decision No. V, dealing with “Nationality of Claims,” Decisions and Opinions, at page 185.Google Scholar [Printed in the Journal, Vol. 19, at page 622.]Google Scholar

3 Not until June 2, 1924 (43 Statutes at Large 253), were all non-citizen Indians born within its territorial limits made citizens of the United States.

4 See Gonzales v. Williams, 1904, 192 U. S. 1, at page 13, holding that a citizen of Porto Rico owed permanent allegiance to the United States without deciding the question with respect to the American citizenship of the individual in question.Google Scholar

The distinction between absolute, or permanent allegiance and temporary allegiance has long been recognized by the Supreme Court of the United States: Carlisle v. United States, 1873, 16 Wallace (83 U. S.) 147, at page 154; United States v. Wong Kim Ark, 1898, 169 U. S. 649, at page 657.

Section 30 of the Naturalization Act of the Congress of the United States approved June 29, 1906, authorized “the admission to citizenship of all persons not citizens who owe permanent allegiance to the United States,” etc.

The Attorney General of the United States in construing this act on July 10, 1908, said (27 Opinions of Attorneys General 13): “This describes exactly the status of inhabitants of the Philippine Islands. They are not aliens, for they are not subjects of, and do not owe allegiance to, any foreign sovereignty. They are not citizens, yet they 'owe permanent allegiance to the United States.'”

5 It was expressly held by the Supreme Court of the United States in Ross v. Mclntyre, 1891, 140 U. S. 453, at page 472, that where a British subject took service on an American ship as an American seaman “He owes for that time, to the country to which the ship on which he is serving belongs, a temporary allegiance, and must be held to all its responsibilities.”Google Scholar

6 Foreign Relations of the United States 1890, page 695.Google Scholar

7 See Ehlers' Case, III Moore's Arbitrations 2551.

8 40 Statutes at Large, at page 885.Google Scholar