For approximately three million years, hominins have been flaking rock that possesses the property of conchoidal fracture (Braun et al. Reference Braun, Aldeias, Archer, Ramon Arrowsmith, Baraki, Campisano and Deino2019; Harmand et al. Reference Harmand, Lewis, Feibel, Lepre, Prat, Lenoble and Boës2015; Semaw et al. Reference Semaw, Renne, Harris, Feibel, Bernor, Fesseha and Mowbray1997). This process of stone tool production is called “knapping,” and it was practiced by Pleistocene and Holocene hunter-gatherers (e.g., Lycett Reference Lycett2011; Shea Reference Shea2017; Williams et al. Reference Williams, Simone, Buchanan, Boulanger, Bebber and Eren2019) and toolmakers and craft specialists in ancient sedentary and complex societies (e.g., Horowitz and McCall Reference Horowitz and McCall2019; Rosen Reference Rosen1997; Shafer and Hester Reference Shafer and Hester1991), as well as by historically and ethnographically documented peoples (e.g., Horowitz and Watt Reference Horowitz and Watt2020; Roux et al. Reference Roux, Bril and Dietrich1995; Stout Reference Stout, Roux and Bril2005; Watt and Horowitz Reference Watt and Horowitz2017; Weedman Arthur Reference Weedman Arthur2018; Whittaker Reference Whittaker2001; Whittaker and Levin Reference Whittaker and Anais Levin2019; Whittaker et al. Reference Whittaker, Kamp and Yilmaz2009). Knapping is also undertaken by modern experimental archaeologists and hobbyists with interests in the evolution, function, production, and artistry of past stone tool technologies (Eren and Patten Reference Eren and Patten2019; Eren et al. Reference Eren, Lycett, Patten, Buchanan, Pargeter and O'Brien2016; Lycett and Chauhan Reference Lycett, Chauhan, Lycett and Chauhan2010; Shea Reference Shea2015; Whittaker Reference Whittaker1994, Reference Whittaker2004). Thus, understanding knapping, knappers, and knapping cultures past and present is a fundamental issue to anthropological research around the world.

Except for the most rudimentary procedures, the knapping of strategically shaped stone tools is a difficult craft to master, involving several counterintuitive and causally opaque operations that necessitate repeated observation and practice (Lycett and Eren Reference Lycett and Eren2019). Even after a person achieves proficiency, stone tool production incurs costs in both time and energy (Mateos et al. Reference Mateos, Terradillos-Bernal and Rodríguez2019; Torrence Reference Torrence and Bailey1983). Another widely attributed but poorly documented cost of knapping is knapper injuries, the focus of this study. Knapped flakes possess razor-sharp edges (Whittaker Reference Whittaker1994) that “do not discriminate between cutting through animal hide or human flesh” (Patten Reference Patten2009:14). Tsirk (Reference Tsirk2014) notes that cutting oneself is inevitable while also emphasizing the risk of silicosis in the lungs and the risks from knapping over the long term, such as tendonitis, tennis elbow, worn-out cartilage, and carpal tunnel syndrome. Lycett and colleagues (Reference Lycett, Kerstin Schillinger, Kempe, Mesoudi, Mesoudi and Aoki2015:163; see also Lycett et al. Reference Lycett, von Cramon-Taubadel and Eren2016) also provide a description of potential flintknapping risks, which can include painful open wounds, blood loss, infection of injuries, and eye damage/loss, in addition to damaged ligaments that might be caused by using an incorrect form. Indeed, injuries among flintknappers are frequent enough that online flintknapping communities share and discuss them on message boards and forums (Facebook 2015; Paleoplanet 2010). In the past some of these injuries might have been fatal.

Given these risks, archaeologists and knappers often discuss injury prevention measures, especially in works aimed at novices (Clarkson Reference Clarkson2017; Ferguson Reference Ferguson2008; Hellweg Reference Hellweg1984; Hodgson Reference Hodgson2007; Lycett et al. Reference Lycett, Kerstin Schillinger, Kempe, Mesoudi, Mesoudi and Aoki2015; Patten Reference Patten2009; Shea Reference Shea2015; Tsirk Reference Tsirk2014; Whittaker Reference Whittaker1994). DVDs and online videos also often include a disclaimer, mentioning the potential dangers of knapping (Eren et al. Reference Eren, Kollecker, Clarkson and Bradley2010). Recommended protective gear, which modern knappers use to varying extents, includes gloves, leather lap pads, leather or rubber hand pads, and eye goggles (Hellweg Reference Hellweg1984; Whittaker Reference Whittaker1994).

Published but sporadic accounts of knapping injuries have appeared in the literature over the past two centuries. In one early example, William Henry Holmes (Reference Holmes1897:61) describes how his knapping experiments could not continue because he “disable[ed] [his] left arm in attempting to flake a bowlder of very large size.” Meltzer (Reference Meltzer2015:130) notes that Holmes's left arm was permanently disabled. Another published example involving an “injury” is that of the Yahi Native American, Ishi, and his time at the University of California, Berkeley. When asked what he would do if he got a knapped flake in his eye, Ishi indicated that he would “pull down his lower eyelid with the left forefinger, being careful not to blink or rub the lid. Then he bent over, looking at the ground and gave himself a tremendous thump on the crown of the head with the right hand” (Pope Reference Pope1918:117). Don Crabtree (Reference Crabtree1966:16) described one of the injuries he received while attempting to re-create the Folsom fluted point: “In an effort to remove a true Folsom fluting flake, I tried this short crutch method. When the pressure was applied, the unfluted preform collapsed, and I drove the antler tipped pressure tool through the palm of my left hand.”

More recently, John Whittaker (Reference Whittaker1994:3) describes one of his most severe injuries from his earliest attempts to replicate stone tools: he managed to drive a pressure flake through his leather glove and into his index finger. When he pulled off the glove, he recalls, “There was a small cut, less than a quarter of an inch wide. . . . There was no pain or blood to speak of, but the finger didn't seem to work. The jovial surgeon who worked on my hand kept exclaiming, ‘I can't believe you severed both the sublimis and profundis tendons with that one tiny cut’” (Whittaker Reference Whittaker1994:3). Whittaker (Reference Whittaker1994:79) also describes a time when he was teaching a flintknapping course. Many of the students did not show up with gloves, and by the end everyone had cut themselves at least once and one participant required sutures. Another experienced knapper, Harold Dibble, who was helping Whittaker with the class, also managed to injure himself while not wearing gloves. He was attempting to help a student remove a flake and “sliced a quarter-inch of skin and flesh off the top of one of his fingers of the hand he was using to hold the core . . . [the flake] still has a patch of skin with recognizable prints stuck to it with blood” (Whittaker Reference Whittaker1994:80).

After 42 years of flintknapping, Errett Callahan (Reference Callahan2001:46) states he lost his sense of control “all because of the damaged, and painful, rotator cuff.” He required surgery to remedy this injury. While attempting an edge-to-edge flaking technique presurgery, Callahan struggled to push his flakes to the far margin of his pieces. After surgery, a repeated “test” found his flakes traveling the full face of the points, noting the “kind of control this flintknapper demonstrated before rotator cuff damage” (Callahan Reference Callahan2001:46).

Recent ethnographic accounts also report knapping-associated injuries. When describing the adze makers of Irian Jaya (Indonesia), Hampton (Reference Hampton1999:267–268) notes that “knapping causes cuts on both the palms and fingers as the ja temen is struck with hammerstones.” Likewise, when describing the women of the Konso region (Ethiopia) who manufacture hide scrapers from stone, Weedman Arthur (Reference Weedman Arthur2010:236) points out, “Several of the novices and elderly hideworkers cut their fingers during production and edge rejuvenation, which resulted in collagen and blood residues identified through microscopic studies of these scraper edges.”

The authors of this study also experienced knapping injuries (but did not participate in the injury survey). As a novice knapper in 2021, N.G. nicked various areas of his fingers while clumsily handling the core he was knapping. He also managed to scrape his knuckles a couple of times and blister the tips of his right-hand fingers by rubbing them on the leather pad while swinging an antler billet. M.R.B. does not consider herself “a knapper” but has tried the craft several times and sustained minor cuts. S.J.L. has regularly incurred minor lacerations to fingers and hands over the course of his 11 years of flintknapping. These never required sutures but were frequently severe enough to require the application of antiseptic ointment and dressing with paper tape for a day or two after the injury.

M.I.E. has experienced many injuries over his 22 years of flintknapping, but by far his worst injury came in 2006 when he was freehand knapping a flake off an obsidian core. At that time, he had been knapping for approximately five years and would likely then have been at an intermediate skill level. He held the core in his left hand and accidentally drove the detached flake into the base of his left pinky (upper proximal phalanx). M.I.E. felt no immediate pain, but after washing off the blood in the bathroom, he got the rather nauseating glimpse of ligaments and bone. This injury required a trip to the emergency room and a series of stitches. M.I.E. recalls that his left hand ached and was essentially unusable for several months afterward. He also once got a small flint chip in his eye, despite wearing protective eyewear. Fortunately, the thin chip was flush against the cornea, and rather than using Ishi's method (described earlier), he was able to remove it with a mirror and some moisture on the tip of his finger. Finally, in 2021, M.I.E. was doing several weeks of pressure flaking for several hours a day. These efforts resulted in severe pain and inflammation in his right thumb, wrist, and distal forearm (which was holding the pressure flaker), requiring rest and the wearing of a brace for nearly a month.

Although these anecdotes illustrate a general sense of inherent danger to knapping, and a broad notion that some sort of personal protective equipment (PPE) should be worn while knapping to potentially prevent or mitigate risks, little is formally, specifically, or systematically known about the frequency, location, or severity of knapping injuries. Nor are there available data that potentially speak to variables that influence the frequency or severity of knapping injuries. Toward this end, we conducted a 31-question survey of modern knappers to better understand knapping risks. Our focus here is on reporting general survey trends on where knapping injuries occur and the frequency and severity of knapping injuries. We also discuss the potential implications of this survey for human evolution and cultural learning issues.

Survey Methods

Our survey included both closed and open-answer questions, with many more of the latter type to allow for as much detail as possible (Supplemental Data SI). Ours is not the first survey to gather information about flintknappers. Whittaker (Reference Whittaker2004) used a mail-in survey to gather data about various knappers and their relationship with the “knap-in” events held around the United States. He asked questions about how they learned to knap, their proficiency, their interests, what they do with their work, and why they attend knap-ins.

Before we distributed the survey and collected data, we obtained approval form the Kent State University Institutional Review Board (Protocol Application #20-327). Typeform.com hosted the list of survey questions, and we emailed a link to 176 individuals. We also posted the link on Facebook, Paleoplanet, and Flintknappers.com. In our emails and postings, we encouraged people to forward the link to knappers who might be interested in participating in the survey. The survey was available to answer for a period of two months from August to September 2020, allowing ample time for the initial group to answer and to pass it along to friends and colleagues. As an incentive, those who responded were entered into a drawing to win a knapped point from the late Bob Patten (Eren and Patten Reference Eren and Patten2019), courtesy of the Robert J. and Lauren E. Patten Endowment at Kent State University. A series of deadline reminder emails followed to those yet to take the survey.

All collected survey data are available in Supplemental Data S1. In several instances, a knapper provided multiple responses for a specific question, so that the respondent sample size does not always equal the answer sample size. For example, our 173 respondents provided a sample size of 198 for the question about their preferred stone raw material because some knappers listed more than such material. Similarly, they provided a sample size of 207 for their most common injury because some knappers listed more than one common injury.

Participant Information and Knapping Habits

Our 173 participants identified as 80.82% male (n = 140), 16.76% female (n = 29), and 0.58% nonbinary (n = 1); three did not provide their identified gender. The age range was large, from 17 to 79 years, with a mean of 45 years. The age at which the respondents began to knap ranged from 5 to 65 years, with a mean of 28 years. This last result broadly conforms to the number of years each respondent has been knapping, which ranged from 0 to 57 years, with a mean of 16.7.Footnote 1 Our respondents’ dominant knapping hand (the one wielding the percussion or pressure tool) was the right hand for 89.02% (n = 154) and the left hand for 10.98% (n = 19), which happens to mirror the average national distribution.

We asked our respondents to self-identify their knapping skill level on a scale ranging from novice (lowest skill level) to intermediate, experienced, expert, and master (highest skill level). Twenty-six of our respondents (15.03%) identify as novice, 51 (29.48%) as intermediate, 52 (30.06%) as experienced, 24 (19.65%) as expert, and 8 (4.62%) as master. Two respondents (1.16%) did not provide an answer.

We also asked our respondents about their knapping habits. First, we asked them about the number of times they knapped per week and the number of hours knapped per session. Some of their answers were difficult to summarize because these were open-answer questions and the times provided varied wildly. To summarize these data here, we devised some simple rules. If a large range was given, differing by more than an hour, the median was taken and acted as the answer for the category. In the case of smaller ranges differing only by an hour, the higher of the two numbers was taken. Some respondents indicated that they knapped more frequently in the past than in the present, in which case the present number took precedence. Lastly, several respondents answered with a number and then added “sometimes more.” In these cases, only the number given was used. Regarding how many times a week our respondents spent knapping, 11 (6.36%) responded zero times, 41 (23.69%) less than one time, 35 (20.23%) one time, 29 (16.76%) two times, 18 (10.40%) three times, 9 (5.20%) four times, 11 (6.36%) five times, 4 (2.31%) six times, and 9 (5.20%) seven times. Three answers (1.73%) were indiscernible. The category encompassing less than one knapping episode per week is highly variable, with responses ranging from every other week to once a year. The zero-episode category includes those who said they did not knap anymore.

Regarding how long each respondent knapped per session, 2.89% (n = 5) answered zero hours, 4.05% (n = 7) less than a half hour, 24.86% (n = 43) one hour, 36.99% (n = 64) two hours, 12.72% (n = 22) three hours, 8.09% (n = 14) four hours, 3.47% (n = 6) five hours, 1.73% (n = 3) six hours, and 0.58% (n = 1) seven hours, with another 1.73% (n = 3) of answers being indiscernible. Additionally, because the zero hours group and the zero times a week group counts do not line up, there might be as many as six individuals who said they knapped zero times a week but might do so every other week. Alternatively, those who stated that they do not knap anymore could be listing the amount of time they would have spent per session knapping.

Respondents provided a variety of reasons for why they knap and how they learned to knap. For 49.13% (n = 85) of respondents, knapping is done for educational/research purposes; for 36.42% (n = 63), it is a hobby; 10.40% (n = 18) listed other reasons; 2.89% (n = 5) noted a commercial purpose; and 0.58% (n = 1) said they knap for practical purposes, with only one person not answering. Nearly one-third of respondents (32.95%, n = 57) appear to have primarily learned knapping from their friends and professors. A large sample of respondents (31.21%, n = 54) were otherwise self-taught. Respondents also learned by observing others (12.72%, n = 22) or from books (8.09%, n = 14), university courses (8.09%, n = 14), videos (4.62%, n = 8), or paid lessons (2.31%, n = 4).

Our respondents use and prefer different knapping tools and techniques and replicate a variety of artifact types. For example, 43.94% (n = 76) prefer hard hammer percussion (hammerstones), 37.57% (n = 65) soft hammer percussion (copper and antler billets), 11.56% (n = 20) pressure flaking (handheld flakers or Ishi sticks of antler or copper), and 6.94% (n = 12) some other technique. In addition, 60.69% (n = 105) prefer handheld support, 31.21% (n = 54) prefer lap support, and 5.78% (n = 10) prefer other methods. Three people use an anvil, and one person did not answer this question. More than four-fifths of respondents (80.35%, n = 139) answered that they like to sit on a low but elevated surface like a chair, bucket, or log. Far fewer (8.67%, n = 15) prefer sitting on the ground or a chair and even fewer (6.36%, n = 11) on the ground; 4.62% (n = 8) have no preference, some other preference like standing, or provided no discernible answer. As to where our respondents knap, 68.21% (n = 118) prefer to sit outside and 31.79% (n = 55) prefer inside; this preference may be due to a lack of suitable indoor space needed to avoid leaving debitage around their living space or to prevent silicosis.

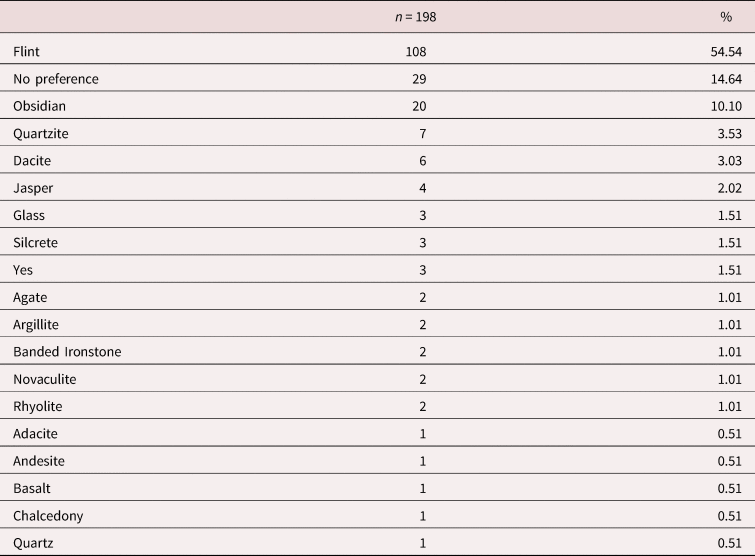

Our respondents’ preferred archaeological culture or artifact type to replicate varied and can be seen in Tables 1 and 2. Their preferred and most often worked stone raw materials can be seen in Tables 3 and 4. Many answers had to be simplified or consolidated to prevent a vast multitude of categories with only one response. For example, “Other Paleoindian” is a consolidation of answers including and similar to the colloquial term for Paleoindian among hobby knappers, “Paleo,” and any other known post-Clovis Paleoindians, excluding Folsom. Well-known Paleoindian styles such as Clovis and Folsom were left unchanged.

Table 1. What Is Your Favorite Prehistoric Culture to Replicate?

Table 2. What Artifact Type Do You Prefer to Produce the Most?

Table 3. What Is Your Preferred Stone Raw Material to Work?

Note: Although it is spelled “adacite” in the survey response, the respondent perhaps meant “andesite” or “adawkite,” which is a type of andesite used for flintknapping in the Andean region of South America.

Table 4. What Is the Stone Raw Material You Have Worked the Most?

Note: We do not know exactly is meant by “republicanite.” Our best guess is Republican River Jasper in Nebraska. It is also known as Smoky Hill Silicified Chalk.

We found that 57.23% (n = 99) of knappers reported they use gloves, 86.71% (n = 150) use some sort of eye protection (e.g., eyeglasses, safety glasses), 64.16% (n = 111) use some form of leather pad, and 4.62% (n = 8) use a mask or fan to keep themselves from inhaling dust. Not wearing gloves could stem from what Whittaker (Reference Whittaker1994:80) calls “a streak of machismo, the sense of danger [that] pleases them.” Others claim that they cannot “feel the stone” when wearing gloves, which is expressed in Whittaker (Reference Whittaker1994). This sentiment is shared by author M.I.E., who, having been substantially influenced and trained by the late Bob Patten, places emphasis on the amount and placement of support in his knapping (e.g., Patten Reference Patten2005, Reference Patten2012:28), something that he feels he cannot consistently achieve while wearing gloves.

General Injury Survey Trends

Injury Frequency

We first asked how often knappers currently injured themselves while knapping. This first question was an open question, and as such, the answers varied substantially. However, there was a trend among answers that allowed us to categorize the answers: 12.72% (n = 22) injured themselves every time, 17.92% (n = 31) very often, 16.18% (n = 28) often, 19.65% (n = 34) not often, 18.50% (n = 32) rarely, 11.56% (n = 20) very rarely, 2.31% (n = 4) never/not yet, and 0.58% (n = 1) could not say with confidence. Only one knapper did not answer.

Next, we asked whether knappers injured themselves more in the past: 74.57% (n = 129) said yes, 22.54% (n = 39) said no, 1.73% (n = 3) did not know, and 1.16% (n = 2) believed the frequency to be about the same.

Finally, we asked knappers how often they got minor cuts: 15.03% (n = 26) said they received a minor cut every time they knap, 27.17% (n = 47) said most times, 17.92% (n = 31) reported every other time, 37.57% (n = 65) said infrequently, and 2.31% (n = 4) never received minor cuts.

Injury Type and Location

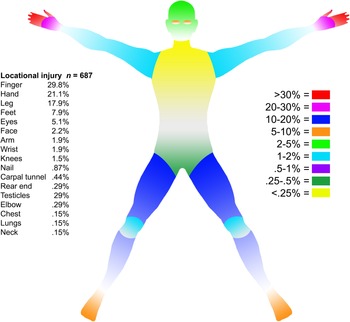

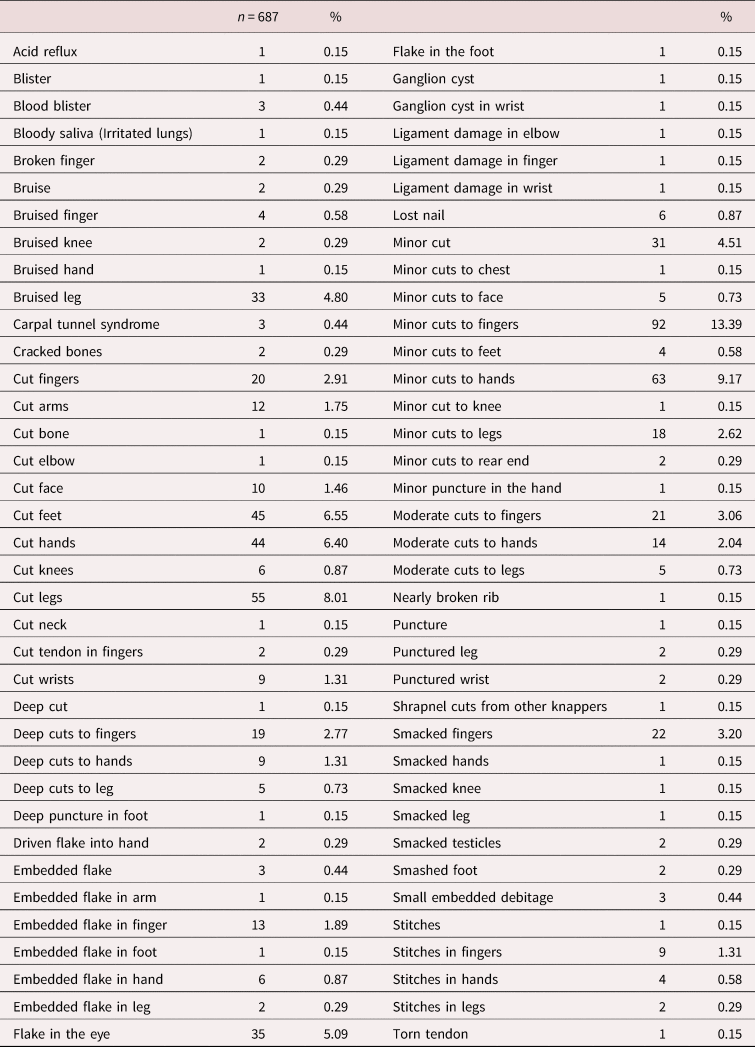

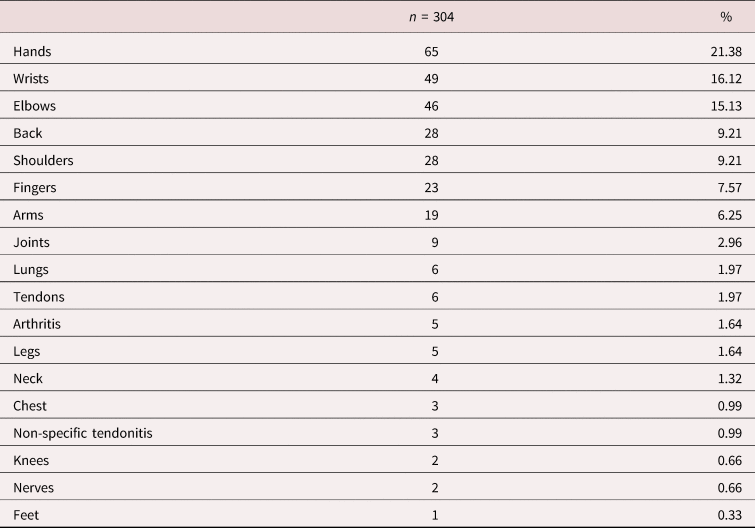

We then asked knappers to list the various types of injuries they have incurred: their most common, most severe, strangest (i.e., most unexpected), and any others they decided to share, including aches or pains. Injuries, which include all variations of cuts, punctures, bruises, carpal tunnel syndrome, and any other results that drew blood or are obviously harmful to the body (n = 687), are reported in Tables 5–7 and shown in Figure 1. Aches and tolls on the body, including joint pain and strain, soreness, and all types of tendonitis (n = 304), are reported in Tables 8 and 9. It is perhaps unsurprising that the most frequent common injuries are cuts to the fingers and hands, with lacerations accounting for more than 30% of reported injuries (Tables 6 and 7; Figure 1). More surprising is that some knappers commonly experience injury types that other knappers consider to be severe. Also surprising is the diversity of injuries, both in location on the body and severity, that the respondents collectively incurred. We describe severe injuries in the next subsection, but it is worth noting that nearly one-quarter of our respondent population (23.12%, n = 40) reported seeking or receiving professional medical attention for a flintknapping-related injury. This percentage would likely be higher, but either due to a “streak of machismo” as discussed by Whittaker (Reference Whittaker1994) or an effort to avoid medical expenses, more than a few respondents noted that they should have gone to get stitches for a cut but decided not to. Instead, they chose to clean and then superglue their wounds together. This method may have only worked because of how sharp flinty materials are and how they tend to cleanly slice through skin without bruising surrounding tissue (Patten Reference Patten2009).

Figure 1. Knapper injury locations and frequencies. (Color online)

Table 5. Variety of Injuries Reported by Respondents.

Table 6. Knapper Injuries, Reorganized and Consolidated.

Table 7. Total Knapper Injuries per Location.

Table 8. Knapper Aches and Tolls.

Note: Where a body part is listed with no descriptor following indicates an area where a toll was felt.

Table 9. Knapper Aches and Tolls, Reorganized and Consolidated.

Additionally, it should be noted that the percentages in Tables 5 and 6 are based on the total number of injuries reported, not the number of respondents. We adopted this approach because the reported data were at times unwieldy, and as already noted, many respondents provided more than one answer to some questions. Yet our choice to report percentages as a function of all reported injuries, rather than as a function of respondents, could potentially influence the perception of some injury categories. For example, 35 individual respondents reported a flake in the eye. As a percentage of all reported injuries (n = 687), an eye flake is only 5.09%, but 20.22% of respondents (n = 173) have experienced this injury.

On the topic of eye injuries, despite 35 reports of flakes in the eye, only one individual reported damage, which was a scratched cornea. No other respondent described any puncturing or cutting of the eye nor any permanent vision problems. Thus, flakes seem to “land” on the eye (as was M.I.E.'s experience described earlier) but only end up causing irritation or some blurriness and are quickly removed. Only a few respondents report seeing a physician to have a flake removed from their eye. But just as debitage can fly into an eye, flakes can also reach other nearby knappers; in one case a knapper's face was cut from someone else's knapping. Moreover, given that 86.71% of respondents report that they use protective eyewear to mitigate such injuries, the risk of eye injury in the absence of modern PPE likely would have been more severe than reflected in these results.

Several of our respondents reported flakes embedded in the skin when a stone fragment is driven into the flesh of the individual and is difficult to remove. Some pieces are only just beneath the skin; others lie deeper. A few respondents report that they currently live with embedded flakes that cause irritation from time to time.

Some knappers managed to hit themselves with their own hammerstones or billets. Sometimes this missed percussion strike resulted in broken bones or a lost nail (one such strike was so bad that the nail had to be trephined). In other cases, smacked fingers bled from the nail, but there were otherwise no serious injuries. One knapper managed to drop a hammerstone on their foot, and two knappers reported that they hit themselves in the testicles.Footnote 2

One knapper reports that they gave themselves acid reflux from pressure flaking by applying physical force while holding their breath. Another reported they had blood in their saliva, which they attributed to silica dust in their lungs.

Finally, most individuals, over their years of knapping, feel aches or have had a toll taken on their bodies—mostly their hands, wrists, elbows, and shoulders but also their backs (Tables 8 and 9). However, as with injuries, there are many locations where aches or body tolls occur.

Examples of Severe Injuries

In this section we describe several individual examples of severe injuries reported in the survey. There are other, and different, severe injuries described in the Supplemental Data S1, but here we simply illustrate some of the dangers that knappers encountered.

One respondent was in their first year of knapping. They were becoming more comfortable with the practice and, after having sustained typical minor injuries, were starting to finish points. They report that they were pressure flaking the edges of a large obsidian biface with an antler tip. The abrader stone they were using was wet, a tool technique they always use when working with obsidian. (They do not report why they kept their abrader wet, but Whittaker [Reference Whittaker1994:83] very briefly mentions that Gene Stapleton wetted his pieces to reduce dust.) This wet abrader technique made their hands and biface wet, which caused the biface to slip and deeply slice open the joint of their index finger. The knapper states that the cut was deep enough to need stitches, but they instead affixed their finger to a stick and wrapped it. Eventually the wound healed with a scar, but the knapper encountered a “odd feeling” for a couple of months when bending their finger.

John Shea (Stony Brook University) describes how he performed a knapping demonstration in Eritrea for some local militiamen and students. He then “decided to show off and make one of these big elongated Levallois points” from obsidian to demonstrate how to flake safely (Shea, personal communication 2020). Saying “this is how you do it safely,” Shea detached the point correctly, but it slipped and cut open his fingertip. It bled profusely but was washed and bound up. He initially thought that this treatment would take care of his injury, because it healed and did not bother him for years; that is, until he closed a window on the finger and dislodged a bit of stone that began to pinch a nerve. He had his physician look at the finger, and eventually John had surgery to remove the rest of the embedded flake. He was not put under anesthesia during the procedure and was asked what was in his hand. He simply told them to wait and see, ending his tale with the surgeon, anesthesiologist, and nurse swearing in surprise at what they found. Figure 2 shows the radiograph of the embedded flake, which is seen in the distal end of the ring finger.

Figure 2. Radiograph of embedded flake seen in the tip of the ring ringer (photo courtesy of John Shea).

While knapping, one knapper had a flake enter their hand and create a “long and deep bone scrape on the top of [their] right hand.” The scrape apparently resembled how wood looks after a wood planer shaves away a layer. The same knapper also managed to sever a tendon in their right thumb, although presumably not in the same incident.

One knapper reported slicing their calf deeply while engaging in some heavy percussion work. They say a palm-sized spall flew off the core, creating a cut in their calf about 1 inch deep and 2.5 inches long.

Another knapper described a wrist puncture wound, likely from a pressure-flaking accident; another knapper then had to bind the injury with a tourniquet. They also say they have had several deep lacerations on their fingers.

On two separate occasions, one knapper had to receive stitches. The first occasion was while pressure flaking a wide biface. They were attempting to push some long flakes off with a lot of force; their knuckle hit the edge of the biface, which sliced the knuckle open. The wound would not stay closed without stitches. The second injury occurred during the fluting of a Folsom point, but this time the knuckle of their right thumb was cut.

A knapper slipped while working a microblade core, and the core cut down to the periosteum of the bone, exposing muscle and one pulsing artery, as they described it. They say their recovery was lengthy but complete. They do not mention the need for stitches, but in answer to another question, they do admit they have sought professional medical attention for an injury, presumably this one.

A knapper's removal of a flake resulted in cutting their left ring finger. The cut ran across the width of their finger and exposed the bone. They required three stitches and a splint.

Similarly to John Shea, one individual reports driving an obsidian flake into their finger just below the nail. The wound did not heal for several days, and they did not realize there was a piece still lodged inside. The flake emerged after the knapper banged their hand on their computer.

Another knapper describes a “dramatic” injury in which they cut the outside edge of their left hand by hitting it on some debitage. This injury cut their ulnar nerve and required stitches. They also report nearly cutting their right ring finger off, resulting in infection.

One knapper reports puncturing an artery in their ankle. They say the wound bled internally, and their foot got huge from the swelling. It eventually healed after months.

Discussion and Conclusions

It is clear from the survey that injury is a real and persistent risk for those engaged in knapping. This highlights the need for safety procedures and the use of PPE, particularly in educational settings (Shea Reference Shea2015) or when conducting scientific experiments pertaining to this craft (Eren et al. Reference Eren, Lycett, Patten, Buchanan, Pargeter and O'Brien2016). This survey provides a more robust indication of knapping-induced injury risks than previously available but is consistent with the sporadic reports of injuries (especially lacerations and risk of injury to eyes) appearing over the last two centuries (e.g., Holmes Reference Holmes1897; Whittaker Reference Whittaker1994).

The results of this survey also permit some conclusions concerning the risk of injuries to prehistoric hominin populations and the implications relating to human evolutionary issues. Although tool use in the animal kingdom is more widespread than previously thought (Shumaker et al. Reference Shumaker, Walkup and Beck2011), toolmaking always involves costs and will only be initiated when the benefits outweigh these costs (Seed and Byrne Reference Seed and Byrne2010). The clear risks of incurring pain and laceration (as well as exposure to infection) are reflected in our study, even with the availability of PPE and modern medical treatment, and occur so frequently that they would have posed a real potential cost to prehistoric populations.Footnote 3 Indeed, other studies have shown that even following modern medical treatment of injury-induced lacerations, infection remains a pertinent risk (about 3.5% of cases), with wounds containing foreign bodies (such as those found in our survey) showing a heightened risk of infection (Hollander et al. Reference Hollander, Singer, Valentine and Shofer2001). In the case of hominin populations where care of injured individuals was not routinely provided by other members of the community, even relatively minor injuries to the hand or eye and infection could potentially have proven fatal if that injury prevented effective foraging. In the case of mothers with dependent offspring, such injuries would not only have threatened the life of the mother but also their offspring. This implies that from its inception, knapping had marked benefits that outweighed its costs and favored its use compared to less risky behavioral strategies. Given that some of the earliest Oldowan knapped stone tools (i.e., those dating to around 2.3 to 2.8 million years old) are associated with animal bones bearing cutmarks (de Heinzelin et al. Reference De Heinzelin, Clark, White, Hart, Renne, WoldeGabriel, Beyene and Vrba1999; Domínguez-Rodrigo et al. Reference Domínguez-Rodrigo, Pickering, Semaw and Rogers2005; Plummer et al. Reference Thomas W., Oliver, Finestone, Ditchfield, Bishop, Blumenthal and Lemorini2023; Sahnouni et al. Reference Sahnouni, Parés, Duval, Cáceres, Harichane, Van der Made and Pérez-González2018; Semaw et al. Reference Semaw, Rogers, Quade, Renne, Butler, Domınguez-Rodrigo, Stout, Hart, Pickering and Simpson2003), the most obvious conclusion is that a desire to obtain a high-value food source (i.e., meat) was sufficiently high, compared to alternative and easier-to-access food sources, to require the use of knapping by hominins at this time. Injury risks would have been combined with other direct costs involved in the manufacture of stone-cutting tools, such as the time spent gathering materials, learning time, and energy expended in achieving both; this emphasizes the significance of this extension of hominin behavioral strategies at this time to an activity that no other living nonhuman primate exhibits today. Although the inception of knapping itself may not necessarily have required cognitive or behavioral capabilities beyond those possessed by the last common ancestor that humans share with the genus Pan (Schick et al. Reference Schick, Toth, Garufi, Savage-Rumbaugh, Rumbaugh and Sevcik1999; Wynn and McGrew Reference Wynn and McGrew1989), the longer-term biological implications of this behavioral shift in strategies (Aiello and Wheeler Reference Aiello and Wheeler1995; Key and Lycett Reference Key, Lycett, Wynn, Overmann and Coolidge2023), as well of the technological beginnings of a more “plastic” world in which virtually all human artifacts are “cut,” cannot be overstated.

Such considerations also have implications for the learning and social learning of stone tool manufacture among hominins. Various mechanisms of asocial (i.e., individual) learning, as well as strategies for social learning or combinations thereof, were potentially available to hominins (Lycett Reference Lycett, Overmann and Coolidge2019). Animal studies have shown that social learning is more prevalent in circumstances where individual learning could prove costly or hazardous (e.g., Chivers and Smith Reference Chivers and Smith1995; Greggor et al. Reference Greggor, McIvor, Clayton and Thornton2016; Kelley et al. Reference Kelley, Evans, Ramnarine and Magurran2003). Comparisons of different tool manufacture and use strategies in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) reinforce this finding. Drawing on work by Humle and colleagues (Reference Humle, Snowdon and Matsuzawa2009), Lonsdorf (Reference Lonsdorf, Clancy, Hinde and Rutherford2013: 313) contrasts chimpanzee termite fishing with the more dangerous activity of ant dipping:

Maternal differences in time spent [termite] fishing were less significant for predicting offspring acquisition. . . . However, for ant-dipping, maternal differences were significant: offspring of more frequent dippers acquired the skill faster and were more proficient. Intriguingly, chimpanzee mothers with young offspring (5 years old or younger) ant-dipped significantly more at trails than at nests, which provided a less risky learning situation for both mothers and offspring.

This suggests that even though rudimentary knapping techniques might feasibly have been learned asocially by hominins (Tennie et al. Reference Tennie, Premo, Braun and McPherron2017), the inherently hazardous nature of knapping is more likely to have encouraged the deployment of any social learning capacities possessed by hominins, which even for the earliest industries would likely have included stimulus enhancement and emulation (Lycett Reference Lycett, Overmann and Coolidge2019). Indeed, some of the earliest (Oldowan) stone tool sites display a mastery of conchoidal knapping mechanics that exceeds simply smashing or breaking stones (Delagnes and Roche Reference Delagnes and Roche2005; Eren et al. Reference Eren, Lycett and Tomonaga2020; Panger et al., 2003; Roche et al. Reference Roche, Delagnes, Brugal, Feibel, Kibunjia, Mourre and Texier1999; Stout and Semaw Reference Stout, Semaw, Toth and Schick2006; Toth et al. Reference Toth, Schick, Semaw, Toth and Schick2006).

An alternative strategy for reducing risk might be to delay the learning or exposure of young infants or children to knapping (Shea Reference Shea2006), especially given the behavior of chimpanzees described earlier. There are also ethnographic analogies for this, such as the hide workers of Konso who are not generally taught knapping until around age 14 (Weedman Arthur Reference Weedman Arthur2010:237) or the adze makers of Irian Jaya where learning of this skill traditionally began around 12 or 13 years of age (Stout Reference Stout, Roux and Bril2005:333). Whether hominins had the opportunity to delay learning in this manner is inevitably speculatory: indeed, studies of tool use and manufacture in chimpanzees would suggest that effective learning is time sensitive, with exposure and practice during infancy and as a juvenile being key to gaining proficiency (Biro et al. Reference Biro, Sousa, Matsuzawa, Matsuzawa, Tomonaga and Tanaka2006; Humle et al. Reference Humle, Snowdon and Matsuzawa2009; Lonsdorf Reference Lonsdorf, Clancy, Hinde and Rutherford2013). However, such considerations may shed light on why more sophisticated strategies for flint knapping, such as handaxe production or more notably Levallois (Lycett et al. Reference Lycett, von Cramon-Taubadel and Eren2016; Muller et al. Reference Muller, Clarkson and Shipton2017), might not have emerged prior to marked changes in hominin life history—particularly the evolution of extended childhoods, secondary altriciality, ontogenetic delay of the teenage growth spurt, or the extended postmenopausal female life span (e.g., Coqueugniot et al. Reference Coqueugniot, Hublin, Veillon, Houët and Jacob2004; Nowell 2010; Nowell and White Reference Nowell, White, Nowell and Davidson2010; Peccei Reference Peccei1995)—when such delayed-learning strategies might have been more feasible. Moreover, cognitively underpinned shifts in social learning strategies (Lycett Reference Lycett, Overmann and Coolidge2019) and changes in hominin life history leading to delayed learning are certainly not mutually exclusive and may also have occurred together, leading to documented changes in the lithic records of later prehistory.

Undoubtedly more trends and relationships are to be found in Supplemental Data S1, but we leave those to be uncovered by our colleagues. The survey data include information on tool choice, raw materials, technologies, and knapper age and experience, among other subjects. For example, a researcher could use our data to potentially assess the following:

• Does injury frequency decrease with knapping frequency (times per week) or duration (hours per session)?

• Does injury frequency decrease or injury type differ between those who do or do not wear gloves?

• Is injury frequency lower or does injury type differ depending on the type of percussor or type of support?

• Does knapping injury frequency change as knapping experience increases?

We encourage other researchers to analyze and add to these questions and data. Future surveys may ask knappers whether they participated in the “Gala et al. survey” to help ensure that data from knappers included here are not repeated (unless a knapper has incurred a new injury since completing the present survey).Footnote 4

Acknowledgments

We are appreciative to Debra Martin, C. Owen Lovejoy, Mary Ann Raghanti, John Shea, Tom Jennings, Mike O'Brien, and John C. Whittaker who provided positive and constructive comments throughout the course of this research and during the peer-review process. We are also appreciative to Fernando Diez-Martin for translating our abstract and key words into Spanish.

Funding Statement

Nicholas Gala is supported by the George H. Odell Anthropology Scholarship Foundation and by the F. B. Parriott Graduate Scholarship. Michelle R. Bebber and Metin I. Eren are supported by the Kent State University College of Arts and Sciences and by the Robert J. and Lauren E. Patten Endowment. This research was funded by the Kent State University Summer Undergraduate Research Experience program.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available in the Supplemental Material.

Competing Interests

The authors declare none.

Supplemental Material

For supplemental material accompanying this article, visit https://doi.org/10.1017/aaq.2023.27.

Supplemental Data S1. Flintknapping Injury Survey Raw Data and Responses.