In the midst of the social upheaval and civil unrest of 2020, Americans were confronted with the hypervisibility of the racial injustice and antiblackness that undergirds our society. Racial health disparities exacerbated by COVID-19—coupled with the police and vigilante killings of Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, George Floyd, Tony McDade, Atatiana Jefferson, Aura Rosser, and countless other Black Americans—led to mass protests on a scale never before seen, both in the United States and elsewhere in the world. As social unrest gripped the United States and rippled throughout the disciplines of archaeology and heritage preservation, we also witnessed the interrogation of dominant historical narratives, rooted in Black death and erasure, which underwrite sites of commemoration globally (Flewellen Reference Flewellen2017, Reference Flewellen2020; González-Tennant Reference González-Tennant2018, Reference González-Tennant2013; Roberts Reference Roberts and Avrami2020a, Reference Roberts2020b; Weik Reference Weik2014; White Reference White2017). Many of these heritage spaces, such as museums as well as national and state parks, are the very spaces where archaeological interpretations of the past are disseminated for wider consumption. The situation demands that we assess what was and what could be different this time around.

We reflect here on the immediate response to the events of 2020, gauge the history and conditions leading up to it, and lay out what we see as the challenges in moving forward. This forum builds on the discussion stimulated during an online salon in which we participated on June 25, 2020, entitled “Archaeology in the Time of Black Lives Matter,” and which was cosponsored by the Society of Black Archaeologists (SBA), the North American Theoretical Archaeology Group (TAG), and the Columbia Center for Archaeology. We use the topics raised in this salon and the responses to them to structure this forum.

In James Baldwin's (Reference Baldwin1993:10) words, we are interested in what prompted so many white Americans “to cease fleeing from reality and begin to change it,” and what role there is for archaeology in this struggle. How might we find ways to engage concretely with the long-standing problem of systemic antiblack racism and examine our own practice—whether through personal and disciplinary activism, teaching and research, or within cultural resource management (CRM), museums, and heritage preservation? These questions set the context for the virtual salon. Over 1,700 people logged into Zoom to witness five Black archaeologists and a museum professional gather to discuss permutations of antiblack racism within the field and how they envision a discipline committed to eradicating racial injustice. A recording of the panel on Vimeo (https://vimeo.com/433155008) was viewed over 2,000 times in the two months following the event. Three archaeologists (Crossland, Dunnavant, and Flewellen) conceived of the salon as the center of an event series, couched between a read-in that took place a week prior and a workshop two weeks later. The goal of the event series was to move beyond discussion alone and into actionable items. The result was the creation of a 40-page resource guide.Footnote 1

Coming to the Table

As part of the online session, panelists engaged as if they were sitting around a table to converse about the everyday practices of racism—both covert and overt—that shape the profession at every level of engagement. During the two-hour virtual gathering, panelists welcomed attendees to have a seat at this table. This metaphorical table was hand-carved by the labor of esteemed scholars and unsung heroes of African descent in the field—such as George McJunkin, John Wesley Gilbert, and the Black-women lab and field crews that worked at Irene Mound through the sponsorship of the Works Progress Administration—as well as the research of James E. Lewis, Oliva Christian, and Theresa Singleton. It is important to note that, in 1980, Singleton was the first Black woman archaeologist to receive a PhD in the United States. In gathering at this figurative table, we recognized that the project to undo ingrained practices of systemic antiblack racism rests on the work of Indigenous scholars and their accomplices, who began and continue to fight against injustice within North American archaeology (Atalay Reference Atalay2006, Reference Atalay2010, Reference Atalay2012; Colwell-Chanthaphonh Reference Colwell-Chanthaphonh2009; Colwell-Chanthaphonh et al. Reference Colwell-Chanthaphonh, Ferguson, Lippert, McGuire, Nicholas, Watkins and Zimmerman2010; Gonzalez Reference Gonzalez2016; Gonzalez et al. Reference Gonzalez, Modzelewski, Panich and Schneider2006, Reference Gonzalez, Kretzler and Edwards2018; Lippert Reference Lippert, Colwell-Chanthaphonh and Ferguson2008; Schneider and Hayes Reference Schneider and Hayes2020; Watkins Reference Watkins2000).

The table metaphor harkens to the Black feminist praxis of Barbara Smith and Beverly Smith (Reference Smith, Smith, Moraga and Anzaldúa1983:131). This praxis is rooted in the conceptualization of the kitchen table as a space where Black people—specifically Black women—gather communally to support one another and collectively envision a world after the dismantling of structural oppression. The table around which panelists gathered was a space of political engagement, where the everyday is inherently political, and the foundation of knowledge production is laid through the sharing of personal experiences. Black feminist thought undergirds both the salon and this article, illuminating the epistemological and pedagogical value in peeling back the quotidian to expose systemic forms of power and oppression (Collins Reference Collins1986, Reference Collins2000). During the salon, no topic was out of bounds as panelists discussed how routine practices—from pedagogy to mentorship as well as within the domains of CRM and public heritage—are informed by practices of antiblackness that systematically exclude people of color.

Moreover, our table also invokes a Black feminist pedagogical decentering of traditional academic spaces as the dominant sphere where knowledge is produced and disseminated. The salon was a public forum, not sequestered within the walls of an academic institution or behind the paywall of a professional conference. Additionally, rather than the traditional practice of reading papers or moving through slide presentations, the role of conversation, as a pedagogical praxis rooted in the experiences of Black scholars, took center stage as the epistemological grounds for knowledge production and the catalyst for change.

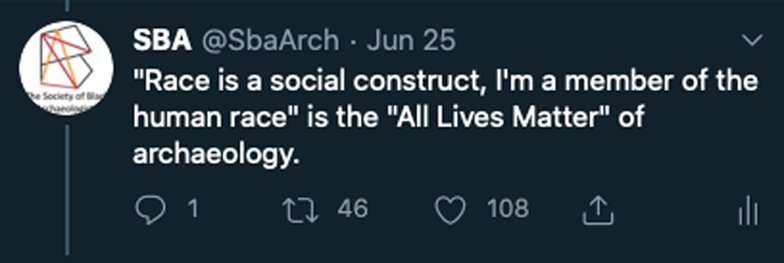

With social distancing due to COVID-19 effectively canceling all in-person academic and professional gatherings during 2020, alternative spaces to commune have been used with greater frequency. Through the use of online spaces such as Zoom and GoToMeeting, virtual panels now reach a wider, more diverse audience. Never before had a gathering of this size pulled archaeologists from their thematic silos to mobilize under the call to shift, change, and reckon with the permutations of racial injustice in the field in order to bring about a more inclusive practice. The use of social media—specifically Twitter—within the program further demonstrated that discipline-shifting conversations were not restricted to the ivory tower and professional conference venues (Franklin et al. Reference Franklin, Dunnavant, Flewellen and Odewale2020).

This forum is structured to retain the atmosphere of the digital collaborative environment. During the virtual panel, Laura Heath-Stout live-tweeted through the SBA's Twitter page. Heath-Stout's tweets provided another space to engage the general public: she posted panelists’ quotes, which allowed the public to continue the conversation during and after the panel. In addition, social media platforms such as Twitter have become the frontline for civic engagement as well as one of the main methods of communication for social movements that incite societal change, such as The Movement for Black Lives (Franklin et al. Reference Franklin, Dunnavant, Flewellen and Odewale2020). Our use of Twitter during the webinar and within this forum highlight the platform as a valid space for the production and dissemination of knowledge. With this in mind, this forum is framed around the tweeted panelists’ quotations that garnered the most traction online. The tweets act as guideposts, much like an interviewer's questions. Following each tweet, the authors collaboratively expand on different points brought up throughout the salon. The result of this collaborative process is the polyvocal discourse that follows. We go beyond reporting the generative conversation that took place in June by presenting a road map for how to move forward. We make a call to not just imagine but follow actionable steps that will lead to an antiracist archaeology in which antiblackness is dismantled.

Within this forum, we draw on the work of João H. Costa Vargas to define “antiblack” and “antiblackness” as the “fundamental, structural, ubiquitous, and unique” logic of Black suffering and subjugation that undergirds the modern and postmodern world (Vargas Reference Vargas2018:182). Our efforts to focus explicitly on antiblackness and antiblack racism should not be confused with an attempt to devalue the very real detrimental conditions of fellow historically marginalized racial groups in archaeology. Instead, this work stands in solidarity with them in a collective effort to transform our field.

What Makes This Moment Different?

The effects of a global pandemic, coupled with police brutality against Black people, provide the social context for this intervention. Together, both made stark racial disparities, already known and experienced by Black Americans, hypervisible to the larger public. State-sanctioned violence against Black people is underwritten within the founding of the United States of America, so it is ages old. But the hypervisibility of Black death seen through the coupling of COVID-19 and police brutality has had effects that have rippled through the profession as archaeologists confront the field's racist foundations. These effects impact every level of archaeological engagement.

It is important to note that the current reckoning within the field is happening on the heels of the slow but steady increase of archaeologists of African descent. According to the Society for American Archaeology's 1994 membership survey, only two out of over 1,600 respondents self-identified as Black (Agbe-Davies Reference Agbe-Davies2002; Franklin Reference Franklin1997a; Zeder Reference Zeder1997:13). The fact that there were enough Black archaeologists in 2011 to prompt the founding of the SBA demonstrates that the concerted efforts to recruit and train Black graduate students have made an impact. Our numbers remain low, however, and disciplinary practices and the professional environment continue to privilege whiteness, which we outline below (Nassaney and LaRoche Reference Nassaney and LaRoche2011). Furthermore, Black archaeologists continue to experience implicit and overt forms of antiblack racism in our field (Franklin et al. Reference Franklin, Dunnavant, Flewellen and Odewale2020:757; White and Draycott Reference White and Draycott2020). In the various sections that follow, we consider the antiracist organizing that Black archaeologists have undertaken and the ways we can build on the organic growth of these practices to more systematically increase and retain Black representation in archaeology.

Envisioning an Antiracist Archaeological Praxis as a Black Feminist Praxis

Responding to the protests of 2020, the authors and our accomplices (defined below) are strategically mobilizing against antiblack racism. The murder of George Floyd and the disproportionate number of people of color, especially African Americans, dying from COVID-19 have underscored racial inequality as America's dominant social problem. Yet, racism does not fully encapsulate all of the vectors of oppression that most Blacks and other people of color currently experience. This is the reason why the Black women cofounders of Black Lives Matter (BLM) frame their antiracist politics within a Black feminist perspective (Ransby Reference Ransby2018).

At the risk of overgeneralizing, there are several key tenets of Black feminist thought. First, there is an entanglement of race, class, sexuality, gender, and other forms of difference that simultaneously oppress Black women. Second, because Black women's positionalities differ from those of Black men and white women, their experiences, perspectives, and struggles are likewise distinctive. And third, Black women's insights into multiple forms of subjugation are invaluable in recognizing and dismantling them.

The interventions of Black feminists are consistently sidelined in conversations around inequality within public and private domains. Black feminists’ analysis of power and the examples they have established in advocating for marginalized communities should be crucial to social justice agendas, writ large. These include Angela Davis's (Reference Davis2003) work on mass incarceration; Kimberle Crenshaw's (Reference Crenshaw1989) interventions in theorizing inequality and difference; Dána-Ain Davis's (Reference Davis2019) research on Black women's reproductive rights; and Patrisse Khan-Cullors, Alicia Garza, and Opal Tometi's cofounding of the Black Lives Matter movement (Khan-Cullors and Bandele Reference Khan-Cullors and Bandele2017). Black feminist scholarship is relevant to historicizing, critiquing, and deconstructing power relations (Alexander Reference Alexander2006; Hartman Reference Hartman1997; hooks Reference hooks2014; Lorde Reference Lorde2012; McKittrick Reference McKittrick2006; Sharpe Reference Sharpe2016), and it has inspired critical work in archaeology (Arjona Reference Arjona2017; Battle-Baptiste Reference Battle-Baptiste2011; Franklin Reference Franklin2001; Lee and Scott Reference Lee and Scott2019; Morris Reference Morris2017; Sesma Reference Sesma2016; Sterling Reference Sterling2015; Wilkie Reference Wilkie2003).

Through intersectionality, Black feminists reveal how oppression has never operated solely along racial divides (Collins Reference Collins2000). We each inhabit positionalities that are simultaneously based on such characteristics as race, gender, sexuality, ableness, class, and nationality. Ultimately, therefore, dismantling racism still leaves misogyny, homophobia, and other structural inequalities problematically intact. This clearly does not suffice. As a case in point, the #SayHerName campaign raised awareness of the fact that police brutality was a problem for not only Black men but Black women as well (Khan-Cullors and Bandele Reference Khan-Cullors and Bandele2017).

Historically, and globally, women and girls of African descent have existed at the bottom rungs of the social order (e.g., Collins Reference Collins2000; Cox Reference Cox2015; Perry Reference Perry2013; Smith and Wilson Reference Smith and Wilson2014). Consequently, Black feminists have consistently advocated for the liberation of Black women, with the understanding that justice for them is justice for all people (Combahee River Collective Reference Smith2000). Furthermore, although antiracist organizing is crucial to the authors, our end goal is an archaeology that is more broadly inclusive and equitable (e.g., Atalay et al. Reference Atalay, Clauss, McGuire, Welch, Atalay, Clauss, McGuire and Welch2014; Heath-Stout Reference Heath-Stout2020; Rutecki and Blackmore Reference Rutecki and Blackmore2016).

Envisioning an Antiracist Archaeological Praxis Rooted in Black Study

As we engage in this work of transforming archaeology, we must reckon with the epistemic roots of the field more specifically. The discipline has witnessed previous interventions (e.g., the New Archaeology, feminist archaeology, post-processualism) whereby archaeologists promoted new agendas, methods, and theories. Indigenous archaeology, in particular, is a unique subfield, with Indigenous scholars and their accomplices delving deeper into notions of “archaeology for the seventh generation” (Gonzalez et al. Reference Gonzalez, Modzelewski, Panich and Schneider2006) and “Archaeologies of the Heart” (Supernant et al. Reference Supernant, Baxter, Lyons and Atalay2020). With the prominence of African diaspora archaeology, the question arises, Is there space for a Black archaeology to emerge on its own methodological and theoretical grounds? If so, what would a Black archaeology entail?

Briefly, Black archaeology is, generally, the study of peoples of African descent then and now. Given its embeddedness in Black Studies and Black feminist praxis, Black archaeology is explicitly political and grounded in intersectional analyses. It entails collaboration with descendant communities and seeks redress, through dialogue with them, of the harms that archaeology and heritage practices have perpetrated against communities of color. Black archaeology's objectives are ever-changing in light of the shifting experiences and needs of the descendants with which we seek to work.

In her pithy, declarative essay, “Rootedness: The Ancestor as Foundation,” Toni Morrison grasps at a definition of Black literature:

I don't regard Black literature as simply books written by Black people, or simply as literature written about Black people, or simply as literature that uses a certain mode of language in which you just sort of drop g's. There is something very special and very identifiable about it and it is my struggle to find that elusive but identifiable style in the books [1984:342; emphasis in original].

We posit that Black archaeology, akin to Black literature, is more than just an archaeology of the African diaspora or archaeology conducted by people of African descent. It necessitates a methodological and theoretical reconceptualization of the manner in which archaeology is conducted. Fundamentally, Black archaeology is rooted in the tradition of Black Studies generally, and Black feminism more specifically (Battle-Baptiste Reference Battle-Baptiste2011; Flewellen Reference Flewellen2017; Franklin Reference Franklin2001; Sterling Reference Sterling2015). Recognizing its Black feminist roots, inquiry and interpretation must be intersectional (Lee and Scott Reference Lee and Scott2019), embracing the ways in which the interstices of race, class, and gender scaffold Black experiences.

Furthermore, Black archaeology is not merely an academic project. The field of Black Studies emerged from the era of social movements in the 1960s and 1970s United States and in tandem with the Black Aesthetic / Black Arts movement (Collins and Crawford Reference Collins and Crawford2006; Rojas Reference Rojas2007). It possessed a firm commitment to the antiracist, empowerment agendas espoused by those concomitant movements. Afro-Caribbean theorist Sylvia Wynter (Reference Wynter, Gordon and Gordon2006), however, argues that Black Studies underwent a process of co-optation in the 1980s as it became more firmly entrenched in academia and the orders of knowledge it was initially intended to oppose. Undoing this co-optation requires an “undisciplining” of Black Studies to reinvigorate the early tenets of the field and to undo the artificial activist/scholar divide. Toward this end, scholars (Crawley Reference Crawley2017; Harney and Moten Reference Harney and Moten2013) have argued that “Black Study”—as opposed to Black Studies—should be predicated on knowledge production and intellectual inquiry beyond the confines of the university. Black Study refuses disciplinary boundaries in an attempt to engage collectively with concepts of Blackness that imagine other ways of knowing and “otherwise worlds” (Crawley Reference Crawley2017).

As with Black Studies writ large, Black archaeology must also reimagine its purpose outside of the strictures of academe in a manner that rearticulates with its activist scholarship roots. Historically, Black archaeology projects—such as the New York African Burial Ground (NYABG), the Estate Little Princess Archaeology Project (ELPAP; Dunnavant et al. Reference Dunnavant, Flewellen, Jones, Odewale and White2018), Walter C. Pierce Community Park Project (Dunnavant Reference Dunnavant2017), and others—emerged as a direct result of community agitation and ensured that descendant community concerns remained paramount to researchers' ambitions. Lessons from the NYABG project demonstrate the importance of “seizing intellectual power” in tandem with municipal power, community power, and the power of the press to control the research aims and assure the proper treatment of African burials and material culture (LaRoche and Blakey Reference LaRoche and Blakey1997). Consequently, Black archaeology has been and must remain purposeful in practice. It rejects research and practices defined in sterile, binary terms of objective-subjective positionality. Archaeology at historic Black sites must be conducted with an explicit politics, whether it is to reclaim the lives of people of African descent from archival erasure or to showcase their social heterogeneity and complexity (Fennell Reference Fennell2007; Ogundiran and Falola Reference Ogundiran and Falola2007; Wilkie Reference Wilkie2003). Archaeology is already politicized—despite the oppositions to “vindicationist archaeology” (LaRoche and Blakey Reference LaRoche and Blakey1997:91)—and our social justice agendas will amplify the significance and broader impact of the research (e.g., Agbe-Davies Reference Agbe-Davies2010a; Epperson Reference Epperson2004; McDavid Reference McDavid2002, Reference McDavid and Stottman2010; McDavid and McGhee Reference McDavid, McGhee, Lydon and Rizvi2010). To the project of Black Study, Black archaeology contributes yet another material archive to explore the breadth of Black possibility and potentiality. To the field of archaeology, it serves as a moral guide with the potential to elucidate historical wrongs and explore forms of contemporary redress. As LaRoche and Blakey (Reference LaRoche and Blakey1997:84) remind us, the spiritual aspects of African American sacred sites should not be lost to the quest for scientific inquiry.

Black archaeology has yet to realize its full potential and by its very nature escapes concrete definition. It is loosely defined by a series of tenets inspired by antiracist, Indigenous, collaborative, Black feminist, and other critical practices within and beyond our discipline that shift—and are allowed to breathe (Crawley Reference Crawley2017)—in a manner that speaks to both the evolving Black experience and the needs of the Black community (Agbe-Davies Reference Agbe-Davies2010b). This reconceptualization not only decenters the canon from the dominant Western anthropological tradition but recenters the scholarship of Black scholars such as Hurston (Reference Hurston1990), Du Bois (Reference Du Bois1899), Collins (Reference Collins2000), hooks (Reference hooks2009), Lorde (Reference Lorde2012), and the Combahee River Collective (Reference Smith2000). This work strives to include an interrogation of the full spectrum of Black life—from the ring shout (Stuckey Reference Stuckey1987) to the “errant subject” (Hartman Reference Hartman2019)—as a site of potential radical theorization.

Returning to Toni Morrison, Black archaeology should be conducted in the same manner in which the novel, according to her, should be written: “It should be beautiful, and powerful, but it should also work. It should have something in it that enlightens; something in it that opens the door and points the way. Something in it that suggests what the conflicts are, what the problems are” (Morrison Reference Morrison and Evans1984:341; emphasis in original). As notions of beauty, power, work, and conflict as well as the problems change over time, so too will our understanding and practice of Black archaeology.

An Antiracist Archaeological Praxis within Public Heritage

Black Lives Matter activists on the ground are demonstrating the possibilities of a Black archaeology through disruptive engagement with historical sites and monuments. The broader BLM movement, with its emphasis on the centering of Black life, has also challenged us to consider the political implications of one of the most essential principles of archaeology and heritage work—preservation. From Cape Town to Richmond to Bristol, a global reckoning has empowered communities to deface, behead, torch, and even drown monuments of historical figures who were commemorated to celebrate white supremacy. Heritage professionals have responded to these conscious acts of destruction and removal with tepid support as well as with division and debate on what kind of afterlife the objects should have (Labode Reference Labode2016). The field's inability to generate a productive response to the latter question is a symptom of a broader challenge of heritage work in the time of Black Lives Matter—namely, that practices must first be fundamentally reimagined through a serious engagement with Black experiences and practices. By doing so, we can unearth longer histories of Black contestation and better inform present preservation work.

In the case of monuments, the privileging of Black life shifts scholarly discourse from a preoccupation with interpretation, preservation, removal, or destruction to a critical interrogation of the very histories we choose to see, excavate, and steward in the first place. For instance, it has been long understood that racist monuments were created to signal power, aggrandize, and legitimize white narratives. But a reorientation toward Black lived experience reminds us that these didactic monuments were also created to be instructive, particularly for people of color. Imposing pro-white-supremacy statues—many of which made their way into public squares with the collapse of Reconstruction—were meant to instill fear, regulate space, and intentionally assault Black people's psyche (Upton Reference Upton2017). Black communities historically opposed these monuments through a variety of strategies, including sustained engagement with defacement that has persisted to the present day. Despite that resistance not always being immediately evident in the material culture (along with the need for more archaeological investigation of these heritage sites), it is important to situate targeted destruction of markers to white supremacy as a type of Black resistance that has a long historical lineage. In turn, Black iconoclastic tradition can inform our work and complicate the field's narrow emphasis on preservation.

Racist monuments have conveyed a message about what warrants protection and what should implicitly be destroyed. Placards frequently obscure alternative ways of knowing monuments, orienting visitors to hegemonic narratives (Flewellen Reference Flewellen2017). In addition, renovations happen silently without recognition of vandalism, and, most dangerously, the monumentality of these racist objects is often normalized as part of the everyday. Moreover, the lesser known history of radical Black dissent is regularly either rendered invisible or demonized. With the Black Lives Matter movement expressing an interest in reclaiming these suppressed histories and marking monuments with visible evidence of contestation, archaeologists and heritage professionals have an exciting opportunity. More specifically, by working closely with broad publics who are actively dictating what should be preserved and what should not, the field can begin to redress the harm it has perpetuated.

Archaeologists and heritage professionals can move toward Black praxis by reevaluating the conventions of the field. For instance, reducing care guidelines and prioritizing the preservation of damage are already being considered. From an interpretive standpoint too, keeping up defaced and destroyed monuments has been proposed as a striking alternative to removal. Similarly, the possible display of damaged monuments in museums is being discussed as a way to cut through some of the risks of reinforcing white supremacist history in white spaces. Although none of these options offers a perfect solution, each signals the imaginative potential of revised and altogether new approaches to public heritage when viewed through the lens of centering Black life.

An Antiracist Archaeological Praxis Requires Us to Leave Our Silos

Theorizing the future of archaeology requires us to examine the field critically in light of the Black Lives Matter protests. This movement calls for a dramatic reorientation of perspectives and systemic changes that address root causes of inequality. Similarly, the untold histories of shared public heritage underscore the need for a commitment to pursuing understudied areas of research, truth-telling, and a reassessment of the propensity to preserve. Archaeology and heritage work are never just intellectual exercises—they have always been political (e.g., Barile Reference Barile2004; Davidson and Brandon Reference Davidson, Brandon, Skeates, McDavid and Carman2012; Franklin and Paynter Reference Franklin, Paynter, Ashmore, Lippert and Mills2010; Gould and Pyburn Reference Gould and Pyburn2017; Joseph Reference Joseph2004; Little and Shackel Reference Little and Shackel2014; Trigger Reference Trigger2006). We cannot in good faith claim an interest in accessing the past without serious engagement with communities that bear the unequal burden of its consequences in the present. Steps toward redress can take many forms—including investing in targeted pipelines leading to diversifying the field; consulting historically harmed communities as necessary intellectual partners; recovering, integrating, and legitimizing local knowledge through co-creation of scholarship and museum interpretation; revisiting our standards of care; and reshaping entire historiographies. Ultimately, harmed communities should decide what meaningful repair entails. We must remain committed to antiracist practices in archaeology that transform our disciplines and, in turn, the politics of our work. The field must be held accountable.

An antiracist archaeology is about rebuilding internally as well as externally. An antiracist archaeology is committed to forging sustainable and nurturing connections among archaeologists of all backgrounds, as well as with communities impacted by archaeological work, community organizers and activists, and those working with smaller historical societies that are also fighting to preserve local histories. bell hooks (Reference hooks2009) challenges all of us to turn toward one another and learn to appreciate the depth and value of each individual and get to know each individual's needs. What hooks refers to as a “community of care” (Reference hooks2009:228) hinges on the development of relationships formed by “praise rather than blame,” which provides the basis of antiracist sentiment in a field still reconciling with past wrongs. Doing this work means being part of a community committed to eradicating antiblack racism within the field as a practice of communal care. With this in mind, it is our collective responsibility to reconcile with the violence this field has done to Black, Latina/o, Asian, Arab, and Indigenous, and other historically marginalized communities in both the past and present and to take an active role in creating an antiracist place of belonging for all.

Practicing an Antiracist Archaeology

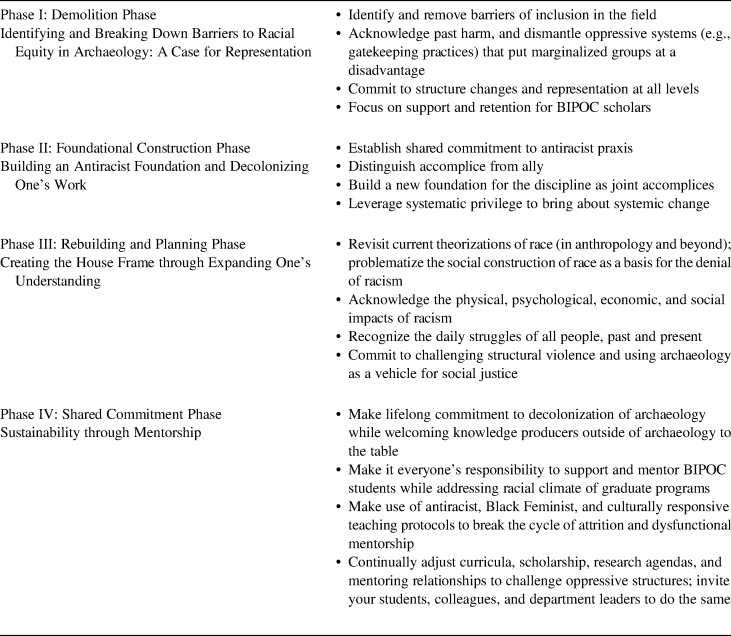

Implementing an antiracist archaeology requires dismantling and restructuring what has become established practice. Here, we advocate for a four-phase approach to building a new foundation for the house of antiracist archaeological praxis (Table 1). These phases incorporate many of the best practices put forth by proponents of antiracist pedagogy in other fields, such as education (Blackwell Reference Blackwell2010; Kandaswamy Reference Kandaswamy2007; Kishimoto Reference Kishimoto2015; McGregor Reference McGregor1993; Pollock Reference Pollock2008; Powell and Kelly Reference Powell and Kelly2017), Black and ethnic studies (Kendi Reference Kendi2019), and women and gender studies (Hanna Reference Hanna2019).

Table 1. Four Phases of Building an Antiracist Archaeology.

Phase 1 involves knocking down the walls of dominant practices within archaeology that perpetuate systems of oppression. Phase 2 invites us to take an active role in building an antiracist foundation to support a new house. Taking lessons learned from Black feminist theorists, critical race scholars, antiracist advocates, and champions of social justice, Phase 3 establishes the framework of this new house by expanding the epistemological legacies on which we draw. Phase 4 centers on mentorship as the key to ensuring the sustainability of an antiracist archaeology.

Beyond this four-phase approach, there is also a need to acknowledge that although many STEM fields—including archaeology—are still struggling to achieve the ideals of “diversity and inclusion,” more recent antiracist scholarship has set its sights much higher, reaching for equity and social justice. History has taught us that diversity and inclusion alone are ineffective solutions (Bradley Reference Bradley2018; Stewart Reference Stewart2016; Williamson Reference Williamson1999). The problem with such solutions is that they are not aimed at changing the systems that reproduce and maintain inequality. “Diversity boxes” are checked by institutions without any real systemic changes, as people are recruited into toxic environments that do not support their retention (Stewart Reference Stewart2016). Instead, a transition to equity and social justice is needed that enables revolutionary change designed to dismantle the current system and rebuild it from the ground up. This work cannot be done by BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) scholars on their own. In each decade since the seminal 1954 Brown v. Board of Education decision, people of color have made similar demands of academic institutions (Bradley Reference Bradley2018; Williamson Reference Williamson1999, Reference Williamson2003:7–34). Many of these historic asks are the same statements made by the authors during the recent “Archaeology in the Time of Black Lives Matter” panel. These demands include the following:

• Hire and advance more racially minoritized faculty and staff through tenure and promotion and into senior-level roles, respectively.

• Make the process of obtaining tenure and merit reviews more transparent.

• Admit more racially minoritized students and offer more scholarships to help them to achieve a degree.

• Train faculty and graduate students to effectively integrate antiracist pedagogy in their classes.

• Revise curricula and syllabi so as to incorporate a greater diversity of voices and perspectives.

• Reduce and respond to incidents of macro- and microaggressions on campus.

• Hire counseling-center staff members who are competent to address the psychological stress of minoritized students.

• Create safe spaces on campus where minoritized students of various identities can share, heal, and organize.

• Recognize the multiple identities of minoritized students and the intersecting oppressions they face on campus (Stewart Reference Stewart2017).

Phase I: Identifying and Breaking Down Barriers to Racial Equity in Archaeology: A Case for Representation

Recent studies have found that the higher number of Black role models a Black student had, the more they felt a sense of belonging at their institution (Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis School of Social Science 2019). It is a true wonder that Black archaeologists who entered the profession in the late 1990s, when there was very little Black representation in the field, remained in the discipline. For students of color, it is imperative that they see themselves in their professors, field supervisors, principal investigators, peers, and the scholarship they are expected to master (Rainey et al. Reference Rainey, Dancy, Mickelson, Stearns and Moller2018).

Students and professionals working in archaeology are more likely to enter and stay in a department, company, or an organization when they feel their talents and skills are valued (Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis School of Social Science 2019). Although attention should be paid to addressing discrimination in the recruitment and hiring practices of organizations at all levels, focus must be shifted away from desires for a “diverse staff” to dismantling barriers that affect the retention of BIPOC scholars. The barriers to meaningful inclusion and retention of Black students, faculty, and professionals in archaeology are often embedded in the ways our institutions operate on a daily basis. Universities, for example, commonly express support for programs that heighten “diverse” experiences across campus, and they infuse ideas of multiculturalism or racial tolerance into their curriculum or mission statements while simultaneously doing nothing to change the fact that many of these campuses are “hostile to the presence of students of color” (Kandaswamy Reference Kandaswamy2007:7) in their failure to recognize the differing needs of different student populations. This hostile environment is further fueled by policies that ignore the daily realities of racism and the power that dominant groups have to suppress the knowledge produced by those perceived to be subordinate (Collins Reference Collins2000; Kandaswamy Reference Kandaswamy2007). What is left behind are layers of challenges that render the invisibility of BIPOC groups in archaeology. These challenges include socially segregated classroom spaces, the delegitimizing of antiracist scholarship and anything that challenges the archaeology canon or attempts to democratize archaeological knowledge, the dismissal of nonacademic persons and their ways of knowing as invalid, and research agendas that perpetuate exploitative and colonial power dynamics. Therefore, the work to dismantle these barriers must itself be layered to address equity at all levels through changes in policies, research methods, pedagogy, established canon, funding streams, and larger power dynamics within the field. Additionally, pathways for Black professionals to obtain leadership positions need to be made accessible.

Phase II: Building an Antiracist Foundation and Decolonizing One's Work

To achieve an equitable, antiracist archaeology, the foundation has to be built alongside accomplices, not allies. There is a profound difference between an ally and an accomplice. An ally is a person who works in partnership with marginalized groups to help change the system that challenges marginalized groups’ basic rights (Rochester Racial Justice Toolkit 2016). This definition is based on the assertion that an ally, as a member of the privileged group, has the ability (when that individual chooses to exercise it) to assist in achieving equity for those who are subjugated (Desnoyers-Colas Reference Desnoyers-Colas2019; Indigenous Action 2014). This concept of allyship positions allies as “Saviors” (Desnoyers-Colas Reference Desnoyers-Colas2019). Allies, however, are not helping to change a system. Instead, they are using it to position themselves as undercover agents of the system from which their power flows.

For this reason, we believe that the foundation of a house of antiracist archaeology is built in collaboration with accomplices. The use of the word “accomplice” may evoke a negative connotation for some readers because of its association with actions perceived to be socially deviant (Harden and Harden-MooreReference Harden and Harden-Moore2019). Any action that is counter to societal norms can be labeled as deviant. The work of creating an antiracist foundation in the discipline is breaking from the norm: it is a break from an oppressive system that was built to advance the histories, ideas, and careers of a privileged few. Being an accomplice means placing oneself in a position that indisputably communicates a stance on advocating alongside BIPOC groups, fully complicit in the struggle toward equality (Indigenous Action 2014; Watson Reference Watson2020). This complicity comes in the form of placing one's privilege, body, career, and future on the line, all for the advancement and equitable treatment of those who have been historically oppressed.

Accomplices are vital to creating an antiracist archaeology because they share a commitment to dismantling the structures of racism that operate at all levels of the discipline: pedagogy, field training, site interpretations, publishing, collections management, funding streams, job placement and advancement, and our professional organizations. The value of accomplices is rooted in their capacity to accept someone else's mission as their own and to voluntarily and intentionally take on the risk of doing so. Accomplices commit the plan to action, and they are culpable or equally to blame for the welfare of everyone involved (Clemens Reference Clemens2017; Indigenous Action 2014; Powell and Kelly Reference Powell and Kelly2017).

It remains essential for accomplices to move beyond statements of solidarity and to use their privilege to bring about change through action. It has become popular for institutions to make statements of solidarity with Black Lives Matter or other movements to dismantle white supremacy. Without the commitment and follow-through to dismantle systemic racism, however, these statements are merely a tactic of self-preservation to quiet complaints and concerns from stakeholders (students of color and their supporters, trustees, and nervous donors; Stewart Reference Stewart2017). In addition to dismantling institutional racism, this work is also needed on an individual level. To this point, Mia Carey (Reference Carey2019) reminds us that this work “begins within committed individuals who are willing to confront the racist ideas and policies that continue to govern the profession and replace them with antiracist ones.”

Phase III: Creating the House Frame through Clarifying One's Understanding of Race

The frame of a house dedicated to an antiracist archaeological praxis builds on one of anthropology's key contributions to our collective knowledge—that of the social construction of identities, such as race and gender. Still, recent rhetoric that denies the severity of racism in the United States has weaponized anthropological understandings of race. This rhetoric argues that because race is a social construct, it is not real, and as a result, racism—or the marriage of policies and ideas designed to perpetuate and normalize racial inequalities—is also not real (Kendi Reference Kendi2019:18). A number of the authors of this article have heard similar statements from their white colleagues. When attempting to illuminate instances of racism, we have been countered with “racism is not real because race is a social construct.” What this sentiment fails to acknowledge is that racism is “more than abstract intellectual tirades” but a daily lived reality that is simultaneously systemic, institutional, and structural (Battle-Baptiste Reference Battle-Baptiste2011:24). In the United States, this daily reality impacts nonwhite racialized groups in many different ways—for example, families of African descent wrestle with a larger wealth and income gap, higher poverty rates, lower rates of home ownership, failing school systems in “urban areas,” and higher incarceration rates than their nonwhite counterparts. Consequently, Ibram X. Kendi argues that “there is no such thing as a nonracist or race-neutral policy,” given that the policies that govern our lives all produce or sustain “either racial inequity or equity between racial groups” (Kendi Reference Kendi2019:18). Failing to engage in conversations about race beyond the idea of race as a social construct further marginalizes and alienates people of color within the field.

Statements such as “race is a social construct” is anthropology's version of multiculturalism, which is similar to the common counterargument to the Black Lives Matter movement of “All Lives Matter.” The statement “All Lives Matter” implores us to ignore race-based differences in favor of a homogenized human race, at the expense of the very real results of processes of racialization that are experienced as unequal access to education, health disparities, and vulnerability to sexual exploitation, among other injustices. Thankfully, the American Anthropological Association's more recent RACE: Are We So Different? project reaches beyond these attempts at homogenization. It also acknowledges that the social perception of race is part of a daily lived experience for Black, Indigenous, and people of color groups, and it presents real challenges with regard to housing, employment, and overall safety in this country (Goodman et al. Reference Goodman, Moses and Jones2012). As Ta-Nehisi Coates (Reference Coates2015:7) observed, “Race is the child of racism and not the father.” Racism is a visceral experience that enacts individual, institutional, and generational violence on the body. An antiracist field requires everyone to commit to social justice and to challenge structural violence—even if the system does not enact violence on one directly. Furthermore, we must acknowledge the daily struggles of peoples, past and present, especially when their experiences differ from our own.

Even though each of the authors has experienced either sexism, antiblack racism, or the entanglements of both, we are all partially empowered through our class status and educational achievements. This has allowed us to act individually and collectively to mentor Black students, collaborate with Black communities in our field projects, and to further decolonize the discipline through our writing and teaching. Still, we are largely working from the bottom up. More of our colleagues are beginning to acknowledge the marginalization of BIPOC archaeologists’ voices and concerns, and they are laboring collectively toward transforming our discipline and profession.

Phase IV: Sustainability through Mentorship

What draws people of African descent to the discipline of archaeology, and how can we ensure that our profession is one in which they choose to remain? Based on a rough estimate of the SBA's membership, the number of Black archaeologists (including those still in graduate school) has increased from a handful to over 80 in two decades. The common ground for many is African diaspora archaeology and a commitment to addressing inequality in the treatment of cultural resources and historical narratives of marginalized groups (Agbe-Davies Reference Agbe-Davies2014; Flewellen Reference Flewellen2017; Martin Reference Martin2019; Ogundiran and Falola Reference Ogundiran and Falola2007; Singleton Reference Singleton1999, Reference Singleton and Morgan2010; White Reference White2010, Reference White2017) within archival spaces (Flewellen Reference Flewellen2020), through community-based research (Agbe-Davies Reference Agbe-Davies2010a; Battle-Baptiste Reference Battle-Baptiste2017; Franklin and Lee Reference Franklin and Lee2020; Jones and Pickens Reference Jones and Pickens2020; LaRoche Reference LaRoche, Skeates, McDavid and Carman2012; Mullins and Jones Reference Mullins and Jones2011; Skipper Reference Skipper2014; White Reference White2010), and in field-based educational practices (Jones Reference Jones2011; Odewale et al. Reference Odewale, Dunnavant, Flewellen and Jones2018). Our commitment to the field extends to forging new pathways forward (Battle-Baptiste Reference Battle-Baptiste2011; Franklin and McKee Reference Franklin and McKee2004; Lee and Scott Reference Lee and Scott2019). Although African diaspora archaeology was certainly a draw, it was also the public-facing and decolonizing practices of archaeologists more broadly that engendered our dedication to a career in this field (e.g., Atalay Reference Atalay2006, Reference Atalay2012; Colwell-Chanthaphonh and Ferguson Reference Colwell-Chanthaphonh and Ferguson2008; Larkin and McGuire Reference Larkin and McGuire2009; Nassaney and Levine Reference Nassaney and Levine2009; Orser Reference Orser2001; Reeves Reference Reeves, Shackel and Chambers2004; Shackel et al. Reference Shackel, Mullins and Warner1998; Singleton Reference Singleton1999). As with archaeologists in general, we also decided that fieldwork and the study of material remains was a much more interesting way to do history than solely digging through the archives.

With regard to Black underrepresentation in the field (Franklin Reference Franklin1997a, Reference Franklin1997b; Franklin and Paynter Reference Franklin, Paynter, Ashmore, Lippert and Mills2010; White and Draycott Reference White and Draycott2020), Anna Agbe-Davies (Reference Agbe-Davies2002:27) once wrote that the “presumed lure of African American archaeology will not be enough to attract and retain black archaeologists.” Although we cannot speak for other Black archaeologists, Flewellen, Franklin, Dunnavant, and Odewale created informal networks with white and BIPOC archaeologists and graduate students who shared our politics and research agendas. This facilitated our determination to finish our degrees. We were also fortunate to have mentors who encouraged our educational and professional development. This helped to weather the racial exclusivity of our departments and archaeology. Consequently, we posit that providing supportive mentorship and addressing the racial climate of departments and professional organizations will help with Black student retention in archaeology. Studies have shown that attrition commonly stems from negative mentoring relationships, which are especially harmful to students of color (Johnson and Huwe Reference Johnson and Huwe2002; Remaker et al. Reference Remaker, Gonzalez, Houston-Armstrong and Sprague-Connors2019; Robinson et al. Reference Robinson, Williams-Black, Smith and Harges2019). Across various disciplines, graduate students’ negative experiences are largely due to either mentor unavailability, problematic mentor behavior, an inability to meet mentors’ expectations, and feelings of inadequacy. Students often feel exploited, especially when their labor goes unrecognized, and they feel powerless to end the relationship (Johnson and Huwe Reference Johnson and Huwe2002; Remaker et al. Reference Remaker, Gonzalez, Houston-Armstrong and Sprague-Connors2019; Robinson et al. Reference Robinson, Williams-Black, Smith and Harges2019). Moreover, students who are already isolated and disadvantaged are expected to master “the basics” of archaeology before they are given the opportunity to do meaningful work that recognizes their own cultural value on their own terms (e.g., Hammond Reference Hammond2015). Although gaining mastery of foundational concepts is an important step toward advanced knowledge, studies have shown that “underserved English learners, poor students, and students of color routinely receive less instruction in higher order skills development than other students” (Hammond Reference Hammond2015:12). These challenges are discouraging for students of color, and as a result, they are often unmotivated to pursue their studies. We have to break this cycle of attrition and dysfunctional mentoring if we are to build an antiracist archaeology.

Educators can employ antiracist and feminist pedagogies as well as culturally responsive teaching (CRT) and advising protocols to facilitate this change. CRT protocols encourage students to bring their own cultural perspective into the process of knowledge production early on—not only after years of studying the canon (Hammond Reference Hammond2015). These practices push educators to form meaningful relationships with their students in order to create a safe space for both parties to continue on a “journey of learning” (Hammond Reference Hammond2015; Kishimoto Reference Kishimoto2015). Furthermore, active learning principles and student collaboration are emphasized over competitive classrooms (Kishimoto Reference Kishimoto2015). Importantly, antiracist and feminist pedagogies require faculty to continually examine their position of power in relation to their students as well as the way it impacts their mentoring (Blakeney Reference Blakeney2005:126–127; Hanna Reference Hanna2019; Kishimoto Reference Kishimoto2015).

Advisors can also improve their success with mentoring Black students by adopting an antiracist curriculum. This includes engaging in scholarship by people of color and by antiracist scholars in general (Kandaswamy Reference Kandaswamy2007). This is essential to every graduate student's development, whether it is specifically related to that individual's thesis topic or not. The goal here is to connect the acquisition of knowledge to an antiracist politics grounded in the continual and reflexive questioning of one's position and assumptions, and to refuse oppressive structures (hooks Reference hooks1994; Kandaswamy Reference Kandaswamy2007). Advising Black students in predominantly white spaces is in itself a political act—one that is strengthened whenever students can take charge of their intellectual development, birth their own culturally relevant research agendas, and realize a wider purpose for their studies outside of academe. Recognizing that all students, not just those of color, benefit from these practices can work to transform archaeology collectively and more broadly.

In departments that are racially exclusive, Black students often feel isolated, and they seek or create alternative spaces for intellectual engagement and fellowship with other BIPOC students (Blackwell Reference Blackwell2010). This is also why faculty of color are often overburdened with mentoring: departments may readily admit BIPOC students, but faculty of color are expected to ensure their success (Social Sciences Feminist Network Research Interest Group 2017). In contrast, an antiracist program requires all hands on deck in mentoring, advocating for more diverse faculty and student recruitment, and valuing public-facing and social justice projects (including community-engaged research) as legitimate scholarship (Nassaney and Levine Reference Nassaney and Levine2009:23–24). Importantly, antiracist practices are learned: it is erroneous to assume that BIPOC colleagues are natural experts in race work. Educators devote years of study to antiracist and feminist pedagogies, and they view teaching and mentoring as ongoing processes (Blakeney Reference Blakeney2005).

Conclusion

This forum is meant to serve as yet another call to action, and we hope that we have offered some signposts as to how to move forward. As archaeologists, we also need to respond to these problems in our daily work lives as much as in our research and teaching. Notwithstanding the great enthusiasm from the audience at the salon, it was striking how great the need for help and guidance was, despite long-standing awareness of these issues (Franklin Reference Franklin1997a, Reference Franklin1997b). It seems that we are at a moment of realization that the current situation cannot continue, and that archaeology must critically examine how its practice has enabled and sustained the status quo. In this forum, we have outlined how the discipline of archaeology must change and how it is currently transforming. We have called for the dismantling of disciplinary structures that serve antiblack racism and the building of a “house” that does not merely recapitulate Black death and suffering but that sustains a praxis of archaeology committed to Black life. In James Baldwin's 1963 letter “My Dungeon Shook,” he called the United States “this innocent country” (Reference Baldwin1993:7), where white people were “still trapped in a history which they do not understand; and until they understand it, they cannot be released from it” (Reference Baldwin1993:8). Many of us, including many in the audience at the salon, write about and engage with postcolonial and decolonial literatures in our research and teaching. Yet, we must ask, how is it that archaeology remains so white? What is it that we as members of this field have failed to understand in order to move forward?

Gloria Wekker echoes and extends Baldwin's observation of whiteness and the perpetuation of racism in her book White Innocence: Paradoxes of Colonialism and Race (Reference Wekker2016). Writing about the Netherlands, but with insights relevant to the United States and elsewhere, Wekker observes that a sense of white innocence fosters “privilege, entitlement and violence” while simultaneously disavowing it (Wekker Reference Wekker2016:18). She argues that there is a kind of “epistemology of ignorance” at play, where white people benefit from racial inequities and hierarchies while remaining at times aggressively unaware of what they gain and how they gain it (Wekker Reference Wekker2016:17). In archaeology, this can be seen in the various departmental cultures that we inherit in our different institutions. This can include a lack of transparency in governance, hiring, or admissions decisions; the fostering of competition between faculty—or worse, between graduate students; and a sink-or-swim attitude to mentoring (or its absence). All of these can conspire to maintain the status quo and actively discourage Black students and faculty as well as those from other underrepresented constituencies. It is therefore possible to both be an outspoken ally of antiracist change and not recognize how one is implicated in the maintenance of the status quo.

How might this inform our thinking about the work ahead for our field? Any discussion of innocence in archaeology swiftly evokes David Clarke's Reference Clarke1973 article “Archaeology: The Loss of Innocence,” written within the time and framework of the New Archaeology but surprisingly relevant today. He begins, “The loss of disciplinary innocence is the price of expanding consciousness; certainly, the price is high but the loss is irreversible and the prize substantial” (Reference Clarke1973:6). Clarke argued that this loss of innocence is and should be “a continuous process” (Reference Clarke1973:6). Perhaps we can think about what is happening right now in terms of another unfolding loss of innocence, but this time, it is one framed not in terms of social evolutionary history and technical advancements but as a loss of innocence that brings the whiteness of archaeology and its entailments more fully into view. This loss of innocence offers both a new set of methods and conceptual challenges for the field. It demands a coherent effort to bring together insights from Black and Indigenous scholarship with feminist archaeology, community archaeology, and post- and decolonial research to make visible some of the foundational and unchallenged assumptions that underwrite what we do. Assumptions, for example, about how the canonical texts we learned as graduate students should be reproduced in our teaching. Assumptions about Black students needing only to see themselves in our syllabi as subjects of archaeological inquiry—not as participants in the production of archaeological knowledge. Assumptions that our field projects can be run as campaigns in which logistics and data collection are prioritized and in which local and community engagement is an afterthought. Assumptions about what constitutes a valid field of study, or an appropriate set of questions or challenges. As Clarke observed, “The consequences arising from the introduction of new methodologies are of far greater significance than the new introductions themselves” (Reference Clarke1973:10). What wide-ranging consequences for the narratives we tell—and the shape of archaeology itself—might we see in the coming decades if we change our methods of writing, researching, and teaching archaeology, and allow this time for a loss of white innocence?

Two days after the June 2020 salon, Whitney Battle-Baptiste tweeted, “The future of archaeology is antiracist” (Battle-Baptiste, Reference Battle-Baptiste2020). Her tweet, a declarative statement, rests as the bookend of this forum piece. To her words we add, “The future of archaeology is antiracist or it is nothing.” The global civil unrest we all experienced in 2020 will have a rippling effect throughout the world for years to come. Those ripples have stripped the field of any question as to whether antiblack racism has permeated its structure (Nassaney and LaRoche Reference Nassaney and LaRoche2011). The answer is undeniably yes. The offerings provided here are a guide to the theory and practice of an antiracist archaeology, inherently Black feminist in nature and rooted in Black Study. This practice requires that non-Black archaeologists—pulled out of their thematic silos—assume the role of accomplices and work alongside their Black colleagues to fight racial injustice at all levels of the profession. Within the work is the imperative that the benefits to the community of archaeology as a whole cannot be underestimated. Finally, the sustainability of an antiracist archaeology relies on an investment in the mentorship of Black students and in the support of Black faculty as part of a practice of communal care.

Acknowledgments

We wish to acknowledge the North American Theoretical Archaeology Group and Columbia Center of Archaeology for cohosting the “Archaeology in the Time of Black Lives Matter” panel with the SBA. We are grateful to Laura Heath-Stout for live-tweeting the initial panel on June 25, 2020; her labor made the format of this piece possible. Our thanks go to Whitney Battle-Baptiste for her ongoing labor within the field to fight against racial injustice and for her tweet that opens the conclusion of this piece. The feedback provided by Cheryl LaRoche and Laurie Wilkie was invaluable, and we thank them both. We express our gratitude to editor Lynn Gamble for inviting us to write this article for the forum. Those of you reading this article who are not actively providing training, mentorship, or direct support to people of color in the field can be part of a community of care by contributing to the institutions and individuals doing foundational work to diversify the field of archaeology and create safe spaces for BIPOC archaeology scholars to thrive. You can educate your students of all backgrounds in the ways of antiracist archaeology and support organizations engaged in antiracist work—such as the Society of Black Archaeologists (SBA), the European Society of Black & Allied Archaeologists, the Rede de Arqueologia Negra–NegrArqueo (Network of Black Archeology) in Brazil, Archaeology in the Community (AITC), as well as anthropology- and archaeology-related programming within Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs).

Data Availability Statement

No original data were presented in this article.