Introduction

The contribution of carers, as ‘people who provide support, in the context of familial or other prior affective relationships, to a person with long-term care needs, experiencing frailty in old age or with serious illness or disability’ (Yeandle et al., Reference Yeandle, Chou, Fine, Larkin and Milne2017: 10), to the support and care of older people is recognised world wide, and researchers internationally are attempting to develop better understanding of its quantity and quality. This paper focuses on the temporal dimensions of what carers do. We take a critical perspective both on time and temporality, and on prevalent assumptions about care that are reproduced in research literature. We argue that the focus on time can be used to generate novel possibilities for research that learns from carers’ experiences. As Milne and Larkin (Reference Milne and Larkin2015) suggest is necessary, we draw on two traditions in care research: ‘gathering and evaluation’, which considers the quantity and nature of caring and evaluates policy and practice; and ‘conceptualising and theorising’ which is concerned with caring in its context, questions prevalent assumptions and critically examines established ideas.

We begin by demonstrating that existing research is constrained in its ability to understand systematically how unpaid carers are now using their time. Whilst several issues have emerged from recent research, addressing these has been hindered by stereotypical views of what carers do, and failure to incorporate more critical perspectives. Time use studies, we will suggest, have potential to deliver more meaningful research, but existing attempts to conduct these have significant limitations, not least because of their attachment to ‘clock time’. We then present and discuss our qualitative research which examined how unpaid carers talk about and work with time, and consider implications for a time use study of unpaid care.

Background: changes in care for older people

Governments are increasingly considering the role of carers of older people. Three of the United Kingdom's devolved administrations have produced carers strategies (Scottish Government, 2010; Welsh Assembly Government, 2013; Department of Health, 2018), with Health and Social Care Trusts in Northern Ireland also producing related strategies (e.g. Northern Health and Social Care Trust, 2011). In England, the Care Act 2014 aimed to improve carer assessments and support, and in Scotland, the Carers (Scotland) Act 2016 intended to enhance carers’ rights and ensure they are supported.

Whilst carers are increasingly to the fore, researchers have debated ongoing processes of change. Examples include changes to the supply of unpaid carers. Whilst some, such as Spiess and Schneider (Reference Spiess and Schneider2003), identify regular relationships between hours of paid work and caring activities of women aged 45–59, others, such as Heitműller and Michaud (Reference Heitműller and Michaud2006), find that changing employment rates have little effect on the supply of care, disassociating these factors. In terms of who will provide care, Pickard et al. (Reference Pickard, Wittenberg, Comas-Herrera, King and Malley2007) project that to 2031, numbers of spouses involved are likely to increase and children will also need to provide significantly more care. Later, Pickard (Reference Pickard2015) finds that numbers of children will be insufficient for this. Relatedly, family structures and dynamics are observed to be changing, with under-researched effects on availability and willingness of relatives to provide care. Bornat et al. (Reference Bornat, Dimmock, Jones and Peace1999) observe two potentially competing scenarios for intergenerational relationships in the context of family forming and reforming: one in which relationships break down with increasing divorces and step-family formation, and one in which relationships are stimulated by these processes to become more flexible and negotiable. In relation to these possibilities, Lin et al. (Reference Lin, Brown and Cupka2017) find that relationship quality is similar across many types of family structures, whereas Pezzin et al. (Reference Pezzin, Pollak and Schone2013) find that step-families are less likely to provide care for their older members, leading to increased use of institutional care as such families withdraw. Others identify competing demands on family carers, such as when they are supporting both parents and children (Spillman and Pezzin, Reference Spillman and Pezzin2000). Baby-boomer attitudes towards care in older age may negatively affect care provision (Finkelstein et al., Reference Finkelstein, Reid, Kleppinger, Pillemer and Robison2012). Policy changes may have unexpected consequences in relation to the tasks that unpaid carers perform, such as shifts from personal care to other tasks in response to the free personal care policy in Scotland (Bell and Bowes, Reference Bell and Bowes2006). Wider societal changes such as rising educational levels, new patterns of migration of both carers and older people, and increased housing wealth may complicate and compound all these trends.

In attempts to quantify the impact of these changes, many of these researchers have used large-scale data-sets, which include data about the carers’ activities and the time they spend on them. The data-sets have, however, significant limitations. The ‘conceptualising and theorising’ literature (Milne and Larkin, Reference Milne and Larkin2015) has been particularly critical of the definitions or care used, which have been characterised as ‘a close relative offering instrumental care to another family member with dependency needs’ (Milne and Larkin, Reference Milne and Larkin2015: 6). This excludes people who may not identify as carers, temporal and spatial aspects of care, and mutually supportive caring relationships. Such criticism is echoed by Ward and Barnes (Reference Ward and Barnes2016) who promote a relational perspective on care, an ethic of care that extends across society, rather than individualist perspectives which emphasise need and provision.

Examples of large-scale surveys to which these criticisms may apply include the Census (Scotland) 2011 Individual Question 9, which asks whether respondents ‘look after or give any help or support’ to various groups on account of disability or older age problems. Understanding Society, the UK Household Longitudinal Study, refers variously to whether people ‘look after or give special help to’ others, and whether they ‘provide some regular service or help’ to others, referring later to ‘looking after or helping’ (Module = caring_w4, caring w4_aidhh, caring_w4.aidxhh, caring_w4.aidhrs). Surveys ask about how many hours are spent, again showing variation: Census (Scotland) 2011 had four time divisions, whereas Understanding Society has seven, and the two surveys cannot easily be compared. Sometimes particular tasks are specified. The systematic review of activity lists by Cès et al. (Reference Cès, De Almeida Mello, Macq, Van Durme, Declercq and Schmitz2017) found considerable variation in these, and suggested that in many cases, carers’ time commitments to different activities were not being effectively measured, as studies take an uncritical view of time as quantifiable clock time.

Temporal aspects of care, and the study of carers’ time use

Simply counting hours of care cannot truly represent the temporal aspects of care, as it relates only to linear time and clock time. Adam (Reference Adam2004) calls attention to the significance of different perceptions of time, and to the related need to explore how these then relate to activities. Hirvonen and Husso (Reference Hirvonen and Husso2012) argue that care work is difficult to reconcile with linear time, being influenced both by the needs of the person being supported (which may of course differ from day to day) and also by the carers’ negotiation of care delivery. Thus care workers, the focus of their study, exercise ‘temporal agency’ in delivering their care work. They negotiate temporality in ways that do not necessarily conform to clock time, as they work with the person they support. We expect that carers will also exercise temporal agency, for example as they work with both clock time, that governs bureaucratic procedures and access to services, and natural time, relating to bodily rhythms and occurrences, that proceeds beyond their control. As James and Mills (Reference James, Mills, James and Mills2005: 14) argue, we need to acknowledge ‘the collusion of people in the making of material life and events through significant timing’, which generates the particular time experiences and perceptions of those who care for older people.

One approach to considering the temporal aspects of care is found in time use studies. These focus specifically on how time is used, and have potential to capture people's own perceptions of how they use their time and its significance for them, thus combining ‘gathering and evaluating’ (Milne and Larkin, Reference Milne and Larkin2015) with the potential for a critical conceptualisation of carers’ time. Whilst time use studies have this potential, they also have some limitations, as we will now argue.

Modern studies of time use date back to the mid-20th century (Chenu and Lesnard, Reference Chenu and Lesnard2006). They collect detailed data on how time is spent, and topics have included the balance of work time and leisure time, rhythms of work, and aspects of family life, especially related to paid and unpaid activities, with the unpaid activities generally being housework and child care (Chenu and Lesnard, Reference Chenu and Lesnard2006). Methods of data collection have included detailed time diaries (e.g. the annual American Time Use Survey (ATUS); Hamermesh et al., Reference Hamermesh, Frazis and Stewart2005) using prescribed time intervals or allowing a respondent to specify how long a particular task took, and questionnaires asking for example ‘how much time do you spend each day on x?’ (Cès et al., Reference Cès, De Almeida Mello, Macq, Van Durme, Declercq and Schmitz2017). Advances in IT and statistics have allowed increasingly complex analyses of data so generated, including identification of patterns and exploration of influences on time use.

Examples highlight the potential value of considering carers’ time use in this way and some key issues. Budlender's (Reference Budlender and Budlender2010) comparative research provides a broad brush picture of the quantity of unpaid care provided using national time use data, with a particular focus on gendered divisions of labour, but is unable to provide detail on the particular nature of tasks. ATUS introduced the topic of time use by carers of older people in 2011, informed by an expert panel, focus groups of carers and cognitive testing (Denton, Reference Denton2012). Using interviews which referred back to a previous day, ATUS reviewed respondents’ use of time and, if respondents stated that they were involved in care, asked which of the activities identified had involved providing care for an older person. The ATUS data provide an important resource for identifying how many people in the United States of America are involved in care of older people, what they do and how much time they spend.

Other work highlights challenges. In some cases, the population involved has not been appropriate, and care provided to older people cannot always be distinguished. For example, Francavilla et al. (Reference Francavilla, Gianelli, Grotkowska and Socha2011), using national time use surveys and EU-SILC (Statistics on Income and Living Conditions), aggregated time supporting both children and adults needing care, and the upper age limit of 74 years for survey respondents meant that no data were available on older carers’ time use. The contribution of the study is therefore limited.

Methodological issues have also been discussed. Cès et al. (Reference Cès, De Almeida Mello, Macq, Van Durme, Declercq and Schmitz2017) reviewed 19 examples of questionnaires that pre-define tasks, and identified omissions in the tasks listed, as well as potential for double counting and mis-counting of time. Bittman et al. (Reference Bittman, Fisher, Hill and Thomson2005) found that questionnaire data tended to over-estimate the amount of time devoted to care as compared with diary data: acknowledging that this finding was perhaps counter-intuitive, they suggested that data collection instruments need refining. Michelson and Tepperman's (Reference Michelson and Tepperman2003) Canadian work linked time use data from Statistics Canada's social survey with data on attitudes and location, thus exploring issues such as carer burden and social interaction, but recognised that the lack of data on time use was a limitation.

Existing research on carers’ time use tends to reflect the status quo, e.g. by pre-defining activities that are considered to constitute care and focusing on particular types of need relating to activities of daily life. Some studies, such as Francavilla et al. (Reference Francavilla, Gianelli, Grotkowska and Socha2011), simply aggregate time spent without identifying particular activities. In the development of the ATUS questions, there was already an indication that the carers involved in focus groups placed greater emphasis on sociable support than did the researchers (Denton, Reference Denton2012: 29). ATUS, in common with other studies, treats tasks as sequential and discrete, at least partly due to the difficulty of grasping concurrent activities (Denton, Reference Denton2012: 32).

The study

In the light of the limitations of the existing care literature for understanding the temporal aspects of care, carers’ perceptions of time and how they use it, we set out to identify, qualitatively, carers’ perceptions of their tasks and time. The research aimed subsequently to inform a time use methodology that would embrace lived experience, without applying stereotypes of either tasks or time. A methodology capable of doing so could, we suggest, have the advantage of both the ‘gathering and evaluation’ and the ‘conceptualising and theorising’ approaches, and could produce empirically grounded understandings of carers’ time use to inform effective policy solutions and improve address to the questions being debated in the care literature.

Research methods

Open-ended interviews were conducted with 62 carers of older adults located across England, Scotland and Wales. We aimed to move away from pre-conceived definitions of care, and took cognisance of evidence from the literature that people conducting often significant care tasks might not necessarily see themselves as carers. Accordingly, in recruiting participants for the study, we informed people that we were interested in speaking with ‘people who provide unpaid care or support (sometimes called informal or family care or support) for older people’. This approach enabled recruitment of participants who saw their activity in different ways, not necessarily as ‘care’.

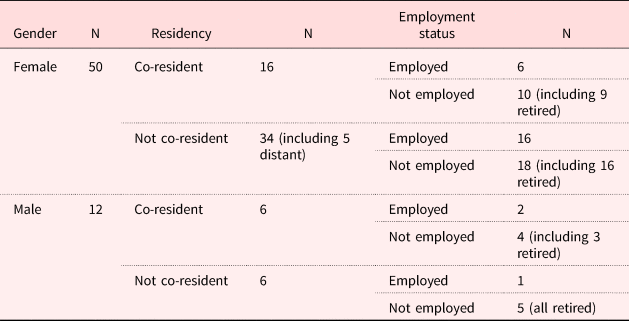

Recruitment was accomplished using snowball sampling, guided by a framework which highlighted the need to recruit male and female carers, those who lived with the person cared for or were not co-resident, and those in employment or not. As Table 1 shows, those recruited fell into all of these categories. The categories were chosen because the literature suggested that these factors were important for influencing experiences of caring: we referred above to the relevance of employment and spatial distribution of families, and the salience of gender has been widely considered (Bertogg and Strauss, Reference Bertogg and Strauss2020). Table 1 provides an overview of the study participants.

Table 1. Participant characteristics

Note: N = 62.

The qualitative interviews aimed to achieve a broad but detailed grasp of carers’ activities and the patterns of and influences on their time use. Interviews were relatively open-ended, permitting participants to explore their own identifications of caring tasks. Topics included: brief information about the person the carer supported, activities completed, development of different activities over time, overall time use, balancing care with other obligations, others who supported within that care network and what they did, and abilities of both the person supported and the carer to carry out basic and instrumental activities of daily living (ADLs and IADLs; questions taken from the Survey on Health and Retirement in Europe, 2004–2006).

Ethical approval and issues

Ethical approval for the study was provided by the Research Ethics Committee of the School of Applied Social Science, University of Stirling, in compliance with the Economic and Social Research Council's Framework for Research Ethics.

There was a need to avoid imposing an identity as ‘carer’ on our participants. This was done by requesting participation from ‘people who provide care or support for older people’, an approach which did not apply any designation. To ensure informed consent, all potential participants were provided with clear information sheets and an opportunity to discuss participation with the researcher and/or with an independent third party before providing written consent. It was important to recognise the potential sensitivity of the subject matter in the interviews. Fieldworkers were careful to respond gently to any distress indicated, allowing people a break, and checking whether they wished to continue. All participants were given information about local support groups for carers, in case they were needing additional support. Finally, it was made clear that participants were not being asked to provide detailed information about those for whom they cared, to protect the confidentiality of third parties.

Analysis

Interview data were transcribed and managed using NVivo 11. Demographic characteristics and the ADL/IADL information were processed using SPSS Release 23. Each transcript was read in detail and summarised as key points memos, with the data relating to carer time use extracted for further analysis. The memos were used to gain an overview of activities, and brought together to get a sense of overarching themes within the data. Interpretation was initially done by individual members of the team, and then refined and verified through discussion amongst team members, as well as by repeatedly returning to and interrogating the transcripts. The purpose of the analysis was to identify how participants used their time, how they represented this, and what kinds of changes and environmental factors came into play.

For example, in the analysis process, initial readings produced a series of representations by carers about how they used their time. They spoke about completing multiplicities of small tasks, the difficulty of describing their use of time, keeping things going, time spent with and away from the person they were supporting, being ‘on call’ and the times taken to do particular identified tasks. These themes were grouped into the larger theme of ‘talking about time’ (considered below), and used to describe carers’ perceptions of time and how they used it. The other larger themes under which we have presented the data were also generated in this way. As they were developed, each was tested by returning to and re-exploring the data to check their validity and robustness. The process is akin to that described by Robson (Reference Robson2011) and others, of initial open coding to identify and firm up themes, then grouping themes into wider categories to build an understanding of the consistencies and variabilities within the data, and testing interpretations through return to and re-interrogation of the data.

In presenting interview data, we use identifiers which denote the country (England, Scotland, Wales), interview number, gender (female, male), residency (co-resident, not co-resident) and employment status (working, retired) of the participant.

Limitations

Despite our best efforts, the sample did not include those providing care and support for older people who take their activity for granted and do not consider they have anything to contribute to research. This is always the case for research in this area: our attempts to make the research as inclusive as possible should have mitigated it to some extent.

We endeavoured to ensure that the sample of participants represented a reasonable range of the variability of carers, covering different genders, ages, whether the carer lived with the person they supported, and whether or not they were in paid employment. We did not attempt to cover other aspects of variability including ethnicity and social class. Experiences of caring do vary with ethnicity (Parveen et al., Reference Parveen, Morrison and Robinson2011), but within the scope and resources of the present study it was not possible to cover these. Social class variations in caring have barely been addressed: this is a research gap.

A further limitation is intrinsic to the use of interpretative methods: although we have systematically interrogated the data, and discussed its interpretation between the research team, there remains a possibility that a different team would interpret the data differently. However, we have followed good practice in verification of qualitative data following Morse (Reference Morse, Denzin and Lincoln2017), using saturation and team cross-checking of interpretation throughout the project process, including the data analysis.

Characteristics of participants

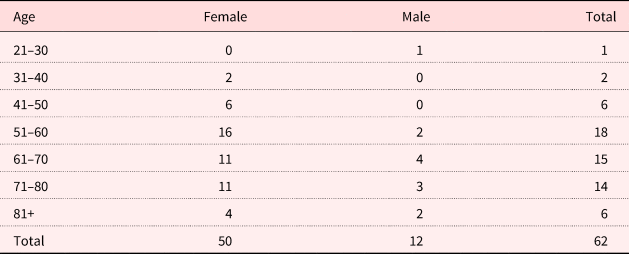

Table 2 provides the age and gender distribution of the participants.

Table 2. Gender and age of participants

Many were in middle age (41–60), reflecting the general population of carers. Several were older carers (61 and over), who are increasingly significant as the literature demonstrates (Pickard et al., Reference Pickard, Wittenberg, Comas-Herrera, King and Malley2007, Reference Pickard, Wittenberg, Comas-Herrera, King and Malley2012). Whilst this is not a random sample, we have achieved age representation, enabling exploration of experiences at different stages of the lifecourse. The participants were also supporting people in different relationships with them, as Table 3 indicates.

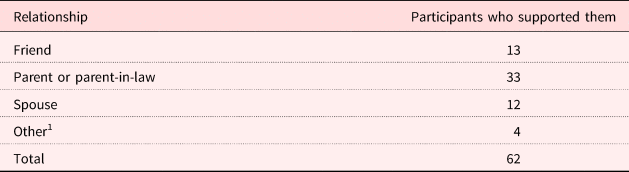

Table 3. Participants’ relationships with older people supported

Note: 1. Former spouse, other relative, neighbour, adult placement.

Participants were caring for 38 female and 24 male older people, and included one person who was caring for a couple. ‘Spouses’ and ‘friends’ each accounted for around a fifth of our sample. Pickard et al. (Reference Pickard, Wittenberg, Comas-Herrera, King and Malley2012) suggest that there is likely to be increasing reliance on unpaid care from these two groups in the future. The interviews then revealed that several participants were involved in supporting multiple people: either more than one older person or younger people (such as children or siblings) in addition to the older person initially indicated.

We examined the various difficulties that both participants and those they supported faced in their daily lives. Table 4 lists these.

Table 4. Participants’ reported difficulties with activities of daily living and instrumental activities of daily living1 for themselves and for those they supported

Notes: Respondents could give more than one answer. 1. Activity lists taken from the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe, 2004–2006, Physical Health, question numbers PH048 and PH049.

Participants clearly experienced fewer difficulties than those they were supporting, though 27 (44%) of them were experiencing issues with one or more ADLs and/or IADLs. Relatedly, three participants described their own health as ‘not good at all’. Older people being supported were reported as having multiple difficulties, with nine reported as having problems with all the ADLs and IADLs, including those presenting cognitive challenges such as using a map (68%) or managing money (61%). The health of 36 older people (58%) was described as being ‘fair’ or ‘not good at all’. Thus, the population being supported in this study includes people with multiple difficulties, linked to both physical and cognitive issues.

Time themes: qualitative data

We now present the findings, addressing, firstly, carers’ own perceptions of the activities which occupying their time; secondly, we consider how carers used their time; thirdly, processes of increase in time use and commitment; fourthly, ‘time shifts’ whereby departures from routine could disrupt time use temporarily or permanently; and finally, how participants managed their caring time in relation to their other time. These accounts move away from linear depictions of time use and challenge assumptions made in previous carers’ time use studies. They show individuals negotiating temporality, exercising agency in their use of and conceptualisations of time, and how change and events may intervene.

Delivering ‘care’

The data provide insights into how participants perceived the care and support they described, and the extent to which they saw themselves as carers. It suggests that understandings of care and support, carers’ own classifications of activities and those of the people they support, and the divisions of labour relating to care activities are all likely to influence carers’ perceptions of time use.

Both the ways carers classified tasks and whether they saw them as care varied. In this case of a woman describing which tasks took the most time, her perception of the same activities seems to have changed:

Shopping takes most time … if we discount the socialising and generally keeping an eye on her, and keeping in touch because I would probably have done that anyway. (E7_FNW)

This participant put practical tasks above socialising and keeping people company when reporting time use, perhaps reflecting widely used assumptions about care, but she also represented the socialising as now part of care, despite expressing ambivalence regarding whether it consumed care time.

Other participants saw socialising and social support as their main activity and expenditure of time, with many listing these first, before going into detail of practical tasks. They perceived social support as especially important, as in this example:

Last night I went down and had supper with her, and that might not sound like an activity, but it is really important companionship. (W_7FNN)

Care activity definition also concerned whether the care or support in question was new or a natural continuation of previous activities. Activity which continued from a time before the person now supported required care was less likely to be perceived to be care-related. Some participants, notably those supporting spouses, highlighted this continuity with what they had done in the past, for example:

I am always the one who does all the cooking, shopping, so there's no change there. (S1_FCR)

Similarly, the following participant referred to continuity in their relationship, linking this specifically to their lack of self-identification as a carer:

I do not see myself as a carer. I see myself as someone who has known her for 20 years and is doing whatever. (E7_FNW)

In some cases, whilst there was continuity of tasks, there were also changes in types of tasks and in perceptions of how time was used. This participant visited the older person (recently deceased) from time to time and had found that certain more instrumental activities had eclipsed others:

I missed having fun time – everything was quite functional; it was around washing, dressing, cleaning, ironing, cooking meals – everything was very functional … that was difficult. (W7_FNW)

A further theme which represented care and support as continuing a positive relationship was that of a ‘return’ for the tasks carried out. Participants who found the tasks enjoyable, or enjoyed the relationship with the older person, are represented by the following three examples:

I feel I do not do anything for anything back, I do stuff because I love doing it. (E16_FNW)

I would say it enriches me. She is very interested in the course I am doing, she loves hearing about that, and it's quite helpful. (E17_FNW)

It is a natural thing to do for a friend. I want to go … I want to add there is no duty about why I go to see her. The joy in her face when we talk about old times, her love of designer clothes – it is meaningful. (E8_FDR)

Participants were significantly in social relationships with those they were supporting, and the agency of the person supported needs recognition: their wishes and preferences could influence what the participant was doing, how they prioritised tasks and the way they did them. For example, E19_FDW described her father's preference for particular routines, and their agreement about how they would manage, despite not always agreeing on the detail:

It works for me and it works for him. It works on the basis that you give what you can give and you do not go around trying to be a martyr. That does not work, especially with me and my dad because we can wind each other up quite easily. (E19_FDW)

Similarly, S1_FCW described how she managed her support for her father, and how this generally meant fitting in with his preferences:

Ninety-nine per cent of the time, it is whatever he wants and I fit around that, but sometimes there is something that I have to do. If he does not want to do it, that is when the tension comes in: so long as I can fit in with him, then life's a peach. (S1_FCW)

In some cases, the relationship was described as one of mutual support, for example, a man supporting a friend stated:

I enjoy our evenings together – we are company for each other. (E15_MNR)

Many participants were sharing the support. This could involve negotiating a division of labour with paid carers. For example, E13_FCW gave her mother breakfast, formal carers then washed and dressed her, and the daughter took over again later. Her mother had until recently also been supported by a friend, but the friend had withdrawn since the mother had fallen, nervous about taking responsibility. Another participant (E4_MNW) spoke about the network of local support in a small community, from which both they and those they supported benefited.

Care relationships are negotiated according to events and preferences, with different people being involved over time. One participant (W7_FNN) described her wish to maintain a clear dividing line between her role as daughter and activities which she saw as care: she had been financially able to engage formal carers to provide support for personal care and her mother's housework, so that she could retain her role as daughter. In a similar vein, W8_FNW described the assistance she gave her mother in terms of small household tasks as a natural part of the mother–daughter relationship, but speculated that if her mother needed physical care, she would perceive that differently.

Importantly, participants did not necessarily represent their activities in accordance with conventional listings of care tasks. In addition to the ambiguities of some activities being variously defined and described, other participants mentioned tasks such as doing recycling, providing computer support, looking after an empty house (after a person had moved to a care home) and extensive travelling to visit the person supported. This was done by non-resident participants, and included one woman who travelled regularly from East Anglia to South Wales and another who travelled 1.5 hours every day to visit her father.

These data all indicate the importance of perspectives on care that are meaningful to participants, and that these are more variable and ambiguous than much of the literature suggests. Care and support may be continuous or changing; care relationships involve reciprocity, the agency of people receiving support and the management of additional sources of support, including paid care-givers and communities.

How carers use their time

When asked to describe the support they provided, very few participants gave a systematic account of a sequence of activities over a day, as would be elicited from a time use diary. Many found it difficult to identify particular tasks, and spoke instead about an accumulation of small tasks:

That is hard to quantify because it tends to be a lot of little things rather than one big chunk … It is lots of little things through the day. (W4_FNW)

Commonly, activities brought an overarching sense of looking after everything, whether a multiplicity of tasks, or taking a more general overview:

…basically making sure she is alright seems to be the main thing that takes up the time – making sure everything is ticking over and she is okay. (S3_FNR)

Caring was often represented as overwhelming. Reports include comments such as:

It's like having a young baby in the house; I sleep with one ear open … I have to be aware every minute what he is doing. (W3_FCR)

It is all day – it starts in the morning and you are doing things all day. (W5_FCR)

It is everything you need to do to keep everything ticking over and make sure that he is safe and has everything he needs. (W6_FNR)

The other side of this for several participants was an ever-present fear of not being there:

It is difficult because I feel if I am not there, I am worried about them … If I take a weekend off and go away somewhere, which does happen occasionally, you can guarantee that something is going to happen while I am away. There is usually an ambulance outside the house when I get back and that teaches that you should not be taking time off because when you do, things happen and they can get hurt – it is reinforcement. (W9_MCN)

Comments such as these were particularly likely where participants felt they were the only person able to offer support, or where the person requiring support had multiple needs, therefore increasing concerns that something could happen. Many participants described themselves as being constantly ‘on call’, often describing this as a particularly stressful aspect of their work:

Having to be there and do things and organise. Sometimes biting my tongue. (E12_FNR)

Within the general sense of being there all the time experienced by many, tasks quantified as time consuming included personal care, such as assistance with showering, especially significant for co-resident carers:

The normal daily routine of showering. I would have to sort him out and give him his breakfast – put it in front of him and quickly have a shower myself. (E12_FNR)

Other examples related to day-to-day domestic tasks:

Making the meal and washing up afterwards. (EH15_MNR)

It is mainly the washing and the cleaning and meals. (W10_FRN)

Many participants supported attendance at medical and other appointments, and this emerged as a significant consumer of time:

Appointments is a big chunk of time and some weeks it is crazy and some weeks are not so bad. (S1_FCR)

Related activity involved liaising with formal services:

I had this day when I spent all day phoning social services and the GP [general practitioner], both of whom said it was the other who had responsibility. (E7_FNW)

Managing support from outside the home was also reported by non-resident carers, and done at a distance. Those who travelled long distances to provide intermittent support would engage in this liaison activity in between visits, thus increasing their use of time even when they were not with the person they supported. Similarly, they reported managing finances at a distance, also a time-consuming task.

These findings emphasise that carers’ use of their time is not easily specified: whilst particular tasks can be identified, the general sense of being permanently on alert is less easily described. Some perhaps unexpected tasks, such as care management and finance management, make significant time demands and are not within the control of the participants. Of particular note is the conduct of support at a distance, apparently outside the time spent directly caring and supporting.

Time increases

For many participants, their activities had increased over time as the person they supported experienced further difficulties. Both range of activities and the time taken to accomplish them increased:

Everything is time consuming, everything takes five times as long because he is slow. (S1_FCW)

Changes of this kind had significant implications for the participants:

I would say getting him ready in the morning because he cannot do it now. I used to get up about quarter to eight, then it had to be half 7, now I have to start about 7 o'clock because it takes so long. (S4_FCR)

Similar experiences were shared by E7_FNW:

I remember the cheese, she wanted mature cheddar, for example, and there were about 20 different kinds of mature cheddar. I think the whole visit took hours and I thought, ‘I cannot do this’.

As a result of this experience, E7_FNW described now shopping alone, highlighting some consequences of increasing time commitment for the participant, and also the potential decrease in activities for the person being supported, as they no longer went shopping. Further, W3_FCR explained how this time expenditure is difficult to change:

I cannot hurry him at all, it is like stirring treacle, I have to give him plenty of time. (W3_FCR)

Increases in time involved were particularly marked for participants caring for a person with dementia. For example:

The worst thing is that he misplaces things continuously from minute to minute, and then cannot find it. ‘Where's my keys? Where's my specs?’ That's the worst part of it, you're spending half your life looking for things. (S1_FCR)

Increasing and more complex medication use was described as having a similar effect:

As the medication got more and more complex, and because she had a swallow problem, it was not the case of knock these tablets back. Everything was painful for her to take, even liquids were painful … that happened on a weekend so for me that was not time critical, but when you know you have to be in work. (W1_FNW)

As well as highlighting the increased time surrounding medication use, W1_FNW suggests the experience of this time may vary based on other time commitments such as work.

The increase in activity time might not always have been noticeable immediately, but the process of doing the interviews allowed carers to reflect back on their roles and the time they committed. A participant who had cared for a relative for more than 12 years described how the intensity of support had grown over time until she was visiting for two to three hours, three or four times a week, doing a wide range of tasks:

I have realised since [his] death, how much time it actually took, because I have so much more time now. (E5_FNR)

Increases in time demands were not necessarily continuous and permanent. They could be temporary, as in the case of E2_FNW, who had provided a period of intensive support following illness, but had then much reduced the amount. If the person being supported moved into a care home, demands on carers’ time could continue, as they visited regularly, but the tasks performed changed, with the care home particularly taking on personal care. However, other tasks, such as financial management and dealing with a former home, might continue.

These data highlight the often cumulative nature of care and support, as well as the potential for increases to be temporary and for changes in circumstances to shift the nature of support tasks. The recognition that carers’ experiences change over time and that when co-residence ceases tasks may change, alerts us to the dynamic nature of caring responsibilities.

Time shifts

Further dynamic aspects of care and support are revealed in data on departures from routine, and the disruptions and alterations these could mean for a carer. These were represented as often very significant for participants, many of whom described decisive events which had precipitated radical changes. They included medical emergencies. For example, a couple who supported a former work colleague (E10_MNR and E11_FNR) had started to do so following his calling for their help after a fall in his house. As time went on, they described how successive incidents had led to them providing increasing support. He eventually moved into a care home: this also precipitated a change in support activity which now became focused on taking trips away from the care home and returning to the house to sort out personal possessions.

Time shifts also included changes in the participants’ own lives, such as changing work hours, re-locating or moving in with the person supported. For example, S2_MCW had postponed a university place to support his relative, and was providing both social support and extensive physical care. S1_FCW had moved into her father's home to support him after a series of difficulties had led her to believe he could no longer care for himself. W10_FRN had reduced her work hours to provide more support for her father: this included the care management and financial support that many participants mentioned as particularly time consuming. Others spoke about changes in their lives that had resulted from their support role: W8_FNW spoke about neglecting her own household work to support her mother, and S5_MNR had given up his hobby of photography and was facing competing needs of other family members for whom he also felt responsible.

In some cases, occurrences were temporary (such as a short hospital stay), but in others, they resulted in significant changes in both the activities and the time use of the participant. E12_FNR's husband eventually moved into a care home. She continued to support him through visits, providing some personal care and taking care of their finances, and had found that when he moved to the care home, she was able to resume activities, such as visiting her daughter, that she had relinquished as his care needs increased.

Moving into a care home was a common event which changed the activities of participants. Discussing her mother-in-law's move, W4_FNW described the kind of change that was typical:

If you were asking me two and a half years ago, it [support] would be every day, three times a day. Her being in care has meant that we have been far less hands-on, because she is now being looked after appropriately. (W4_FNW)

Instead of providing personal care and domestic support, assisting with making appointments, managing finances, liaising with formal services and assisting with outings, this participant was now visiting and assisting with finances.

These big events, whether they have temporary or longer-term impacts, are clearly significant in discussing carers’ time use. Many of the participants saw them as significant influences in their lives. They were often the recipients of changing circumstances that altered and often increased the demands on their time in ways over which they often had little choice or control.

Managing life time

Understanding how care relates to people's whole time activity is clearly important: we have already identified that taking on care could affect participants’ lives significantly. The logistics of providing support whilst also fulfilling other roles and obligations could be complex. Struggling to balance their supporting role with other commitments, participants described how the support activities affected their time:

By the time you have been to work, sorted him out, gone home, you feel too tired to do anything. It is like a treadmill at the moment, going round and round. (W10_FNW)

There were several examples of how care could affect how other roles were fulfilled, for example:

I feel I cannot really give up any more of my time because I am depriving my husband of company if he is wanting to do anything. It is a pressure there as well. (S3_FNR)

Similarly, W8_FNN found it difficult to identify specific time-consuming activities, but described how having to take time out of the rest of life could be a problem:

There is not any one thing that particularly takes up the time. It is the fact that you have to leave what you are doing to come here to do it. (W8_FNN)

Where participants felt under pressure to provide care, the time spent was also experienced as a problem:

I used to think if I do not do this, who will? Then I felt guilty that I felt that. (E6_FNR)

Similarly, E14_FNR highlighted the impact of such pressure:

Sometimes I dread going to see her, but I feel I have to because I know she depends on me to come in and talk to her, and that can be quite a stressful thing.

This feeling may have influenced the activities she described as most effortful:

Listening to the list of maladies and unfortunate goings on, and arguments with the doctors, and difficulties with the drugs and all that… (E6_FNR)

Not all participants saw the support activities as distracting from other tasks, or as getting in the way of the rest of their lives. E16_FNW, for example, took pleasure in her supporting role, and prioritised it over other activities:

Material things do not matter. If the ironing has not been done, I will go and see [him]. People come first. Families and people come first. If there is stuff to be done at work, I will stay after and do that, rather than do it when I am with [him]. (E16_FNW)

E18_FNN was a student, supporting an older friend who shared mutual interests:

Occasionally I might have deadlines, but to be perfectly frank, by the time I have sat down and had two hours with her, I feel so much better. I get more out of it. (E18_FNN)

Thus, care time contextualised in people's wider activities and responsibilities indicated a range of perspectives, including both significant perceived pressure, but also examples of choice and preference from people who prioritised and took pleasure from their care activities. Some participants seemed to resent the time that caring took away from other activities, seeing it as time lost, with others preferring to provide support over other demands which might be adjudged more pressing. This is a further expression of different perceptions of time that come into play when carers discuss their time use.

Discussion

The focus on temporal aspects of caring generates some new insights relating to the literature on caring considered earlier. These insights relate both to evaluating and conceptualising issues.

Many of the carers were combining their caring with paid work, and the discussions of the balance of time between different tasks are particularly pertinent. Whereas often the literature has been concerned with the mutual impacts of caring and paid work on the supply of care, our study has considered the realities of caring for people who are attempting to sustain their paid work alongside, working with their time according to their perceived priorities and thus exercising temporal agency (Hirvonen and Husso, Reference Hirvonen and Husso2012). Impacts for the individual have been demonstrated in several examples, including some where the balance has proven difficult. Time pressures experienced by many carers are significant, but their impact is not necessarily perceived at the time: in many cases, people report in retrospect that they did not have control over their time. They could be said in this respect to have limited temporal agency (Hirvonen and Husso, Reference Hirvonen and Husso2012).

One concern in the literature is the availability of carers, and whether future demand can be satisfied. Our broad definition of carers during recruitment avoided some of the presumptions evident in the large-scale surveys and recognised that the designation ‘carer’ might not represent people's own perceptions of their activities. The study therefore included several people who did not fall into the usual categories of child or spouse carer. The friends, neighbours and other relatives who care are less well recognised than those who fit the more conventional categories: they do not necessarily deliver personal care or intensive support, but the sociability and small services they provide can be vital to the older people concerned. The accounts of the time given by such people indicate that for the older people, their time in their own homes was at least more pleasurable and in some cases extended through the care received. These contributions, not often recognised in the caring literature, are providing largely unaccounted for caring time. They support the adoption of an ‘ethic of care’ (Barnes, Reference Barnes2012) approach which can consider care as distributed across communities, and broaden consideration from those usually designated carers. Caring time does not only come from those conventionally captured in surveys, but includes time identified as significant and important by people who work with it creatively to satisfy themselves and others, as James and Mills (Reference James, Mills, James and Mills2005) propose.

The dynamics of changing family structures are demonstrated in several ways. In reference to the debate about whether more distant kin or non-kin carers would commit to supporting older people (Bornat et al., Reference Bornat, Dimmock, Jones and Peace1999; Pezzin et al. Reference Pezzin, Pollak and Schone2013; Lin et al., Reference Lin, Brown and Cupka2017), the carers included showed continuing commitment: e.g. they included support for an ex-partner and for non-kin. We also identified strains in kin relationships around caring, where its nature and extent had become increasingly difficult over time so that, despite their commitment, carers chose to cease their paid work or get additional help with caring. These changes involve the negotiation and renegotiation of biographical time as people review their obligations and take on different commitments through their lifecourse.

Attitudes to care varied, showing a range of different motivations and views. Some of these were directly linked to time considerations, as for example people who were nearby and had the resource of time to spend caring. Other attitudes included obligation due to types of relationships, usually kin relationships, but also factors such as love, respect, friendship and enjoyment of company. Having time and whether to use it to care are essentially attitudinal matters which influence care provision.

The impact of policies on carers’ time use was visible mainly in the pressure and the lack of support many of them experienced. These may be alleviated by recent policy developments which have recognised the contribution made by carers and focused policy makers’ attention on supporting them. The extent to which the temporal challenges of caring are met by recent policy innovations is yet to be seen: however, it is clear that the policies continue to be premised on counting hours of care and services that operate on clock time.

Migration had also affected carers’ work and their use of time. Whilst attention has been paid in literature to the spatial aspects of caring – that it can be done at a distance, for example – the surveys have not captured these temporal dimensions. The extent of travelling to care was notable and clearly used considerable amounts of time and energy from those involved. The sustainability or otherwise of such long-distance caring relationships and their temporal implications is an aspect of the possible fragility of the supply of care that has not been captured in the literature.

Caring tasks highlighted in our study were more extensive than and somewhat different from those identified in the literature which tends to consider personal care and intensive support more fully than financial management, sociability and new tasks, including recycling or computer help, all perceived as significant by our participants. The implication of this is that research on the supply of care is omitting consideration of much caring work that is already being done, and the continuing need for that into the future. Conceptualisations of caring thus need to be reconsidered to capture such changes.

Implications for studying carers’ time use

Time for carers is complex. Our study has shown a wide range of time-consuming tasks, perceived as both positive and negative; change over time has emerged as significant, whether gradual or precipitated by events, permanent or temporary; care and support may be perceived as integral to life or as additional difficult work; how care time is contextualised, affects and is affected by the rest of people's lives is also variable. The different perceptions of time that emerge echo Adam (Reference Adam2004) who stresses the need to explore how these relate to activities. Care is difficult to reconcile with clock time and both clock time and natural time can prove challenging to negotiate. The ‘temporal agency’ of carers can be seen as they balanced their care work with the rest of their lives, got through difficult days, liaised with formal care providers and dealt with emergencies as they arose.

The discussion here could prompt questioning the feasibility of collecting data on carers’ time use. We have observed a wide range of definitions of tasks; where tasks are recognised as care and support, there seems to be variation in perceptions of the time they involve, perhaps influenced by whether or not they are enjoyed; trajectories over time can vary; care can be routine, or there can be shocks and challenges that precipitate temporary or permanent change; and the ways in which care collides with or complements or consumes the rest of people's lives are also variable. All these factors suggest that carers’ time use may be difficult to capture using methods which rely on linearity and structure.

However, once the difficulties and issues are recognised, there remains a need for carers’ critical contribution to care for older people to be understood and quantified more effectively than previous measures have delivered.

Our study suggests several implications for research on carers’ time use. Firstly, the interviews enabled people to reflect on their time use and to identify aspects that they had not necessarily previously considered, such as how they were using their time, how they might express their use of time and how their care tasks fitted in with their other activities. A time use methodology for carers should, we suggest, also enable participants to think through their use of time, without pre-empting their views by, for example, providing only narrow options or pre-defined time-scales.

Secondly, a time use study needs to be capable of capturing a variety of tasks wider than those often listed in large-scale surveys. We identified tasks that are not conventionally recorded, such as travelling, in many cases long distances, regularly to support people living far away. Our participants variably included social support in their care and support accounts: a time use data collection tool would need to be clear whether it is focused on people's perceptions of their care in an open-ended way, or whether it requests participants to include specified tasks.

Thirdly, a study needs to capture both routine and non-routine tasks, such as the emergencies discussed. An emergency could be a temporary issue that would resolve, with the participant reverting to their former pattern of activity, or it could produce a step change in the quantity and quality of care provided. One way of addressing this issue might be to collect data over a longer period, to increase the likelihood of capturing emergencies. Alternatively, a larger sample could increase the likelihood of ‘emergencies’ being captured, although the size of sample needed remains difficult to calculate.

Fourthly, a further challenge is that of capturing the ‘permanently on call’ aspect of support that many participants identified: this did not easily translate to a list of specific tasks, but was nevertheless perceived as a significant part of caring. The data collection has to take account of this permanent alert experienced by many carers, often alongside other tasks. If a time use study intends to quantify how much time is spent caring, then multi-tasking means some tasks may not be specified (this point is also made by Cès et al., Reference Cès, De Almeida Mello, Macq, Van Durme, Declercq and Schmitz2017). However, if a study aims to understand how time is used, it has somehow to take multi-tasking into account.

Fifthly, caring activity fits into and interacts with people's other activities in various ways. This implies collecting data which captures participants’ whole time and full range of activities, including activities that are not care. However, the pressure on their time that carers experienced suggests that completion of an open-ended diary or a contemporaneous ten minute by ten minute account of time use is likely to be particularly difficult.

Conclusion

The contribution of carers of older people is undeniable though changing, as the debates in the literature demonstrate. We identified important gaps in our understanding of what unpaid carers do, and some particular drawbacks to attempts to quantify their work using large-scale surveys. We presented time use surveys as a potential alternative, which could provide a more open-ended and detailed understanding of unpaid carers’ contributions. Since previous time use work with carers has produced only limited results, our qualitative work with carers aimed to unpick conceptually aspects of time use from carers’ own perspectives and to assess the implications of this more in-depth understanding for developing a study of carers’ time use.

The prospects for a study are both challenging and enticing. A time use study which can represent the realities and complexities of carers’ time use as we have elucidated them, which takes account of their own perceptions of time use and uses a data collection tool that is feasible for them in the context of their highly pressured time, could begin to help understand far better how carers achieve their contribution and, most importantly, deliver understanding of where their own key challenges are, to inform developments of better ways to support them to continue their work.

At the time of writing, the team is collecting time use data from those who provide support and care for older people. In contrast to the ‘typical’ time use diary which records activity every 15 minutes, our data collection tool is activity-led and partially populated to reduce the workload on participants. These data will be compared with data from large-scale surveys to assess whether the time use approach can in fact deliver improved understanding.

Author ORCIDs

Alison Bowes, https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8594-7348

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the Economic and Social Research Council for funding the research, to the participants who generously gave their time and to the fieldworkers, Maria Cheshire-Allan, Corinne Greasley-Adams, Jayne Kinnear, Deborah Kwan, Kathleen Lane and Susan Murray.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Economic and Social Research Council. Centre for Population Change ESRC reference ES/K007394/1

Ethical standards

Ethical approval for the study was provided by the Research Ethics Committee of the School of Applied Social Science, University of Stirling, in compliance with the Economic and Social Research Council's Framework for Research Ethics.