Introduction

Attitudes towards ageing that have manifested in response to the COVID-19 pandemic are largely shaped by narrow and harmful age biases in public discourse and response measures (Colenda et al., Reference Colenda, Reynolds, Applegate, Sloane, Zimmerman, Newman, Meeks and Ouslander2020; Ehni and Wahl, Reference Ehni and Wahl2020; Morrow-Howell et al., Reference Morrow-Howell, Galucia and Swinford2020). Pandemic news reports have portrayed older adults as helpless, frail and incapable of social contribution (Ayalon et al., Reference Ayalon, Chasteen, Diehl, Levy, Neupert, Rothermund, Tesch-Römer and Wahl2021; Morrow-Howell and Gonzales, Reference Morrow-Howell and Gonzales2020). Policies such as age-based confinement associated older age with vulnerability and dependency, creating a ‘double pitfall’ of institutionalising generational division and sustaining ageism (Previtali et al., Reference Previtali, Allen and Varlamova2020). Age-based resource allocations prioritised treatment for younger versus older adults in health-care settings (Farrell et al., Reference Farrell, Ferrante, Brown, Francis, Widera, Rhodes, Rosen, Hwang, Witt, Thothala, Liu, Vitale, Braun, Stephens and Saliba2020; Hostiuc et al., Reference Hostiuc, Negoi, Maria-Isailă, Diaconescu, Hostiuc and Drima2021). Negative attitudes towards ageing additionally gained widespread presence on social media where COVID-19 is referenced as #boomerkiller, #boomerremover and #elderrepeller. Both implicit and explicit biases reflect attitudes towards ageing that stigmatise older adults as a homogenous and vulnerable group of people (Monahan et al., Reference Monahan, Macdonald, Lytle, Apriceno and Levy2020; Swift and Chasteen, Reference Swift and Chasteen2021), belying the diversity among adults age 65+ (US Census Bureau, 2017; Administration on Aging, 2020; Akinola, Reference Akinola2020).

The need to critically examine attitudes towards ageing in the context of the pandemic is underscored by research that indicates older adults are faring the pandemic with greater resiliency in moods and expectations than younger adults (Whatley et al., Reference Whatley, Siegel, Schwartz, Silaj and Castel2020). A national poll of nearly 3,000 Americans found that older adults felt less isolated during the pandemic than all other age groups (Stepko, Reference Stepko2021). Research additionally suggests that views on ageing are predictors of health and wellbeing (Kornadt et al., Reference Kornadt, Voss and Rothermund2017; Levy, Reference Levy2009). Positive attitudes towards ageing generally correlate with improved mental and physical health (Bryant et al., Reference Bryant, Bei, Gilson, Komiti, Jackson and Judd2012; Low et al., Reference Low, Molzahn and Schopflocher2013), whereas negative attitudes towards ageing correlate with lower mental and physical health (Low et al., Reference Low, Molzahn and Schopflocher2013; Wurm et al., Reference Wurm, Warner, Ziegelmann, Wolff and Schüz2013). Ageist attitudes put both older and younger adults at risk of internalising negative associations with ageing and worsening trajectories of physical and mental health across the lifespan (Levy, Reference Levy2009; Kessler and Bowen, Reference Kessler and Bowen2020; Kornadt et al., Reference Kornadt, Albert, Hoffmann, Murdock and Nell2021).

This article presents findings of a photovoice study where older adults were invited to take photographs and describe how the pandemic prompted them to shift their attitudes towards ageing in place. Data call attention to ways older adults valued ageing in place in response to physical, environmental, social and technological factors that changed dramatically during the pandemic. Findings support a conceptual framework of ageing as multi-dimensional, multidirectional and multifunctional (Kornadt et al., Reference Kornadt, Albert, Hoffmann, Murdock and Nell2021). Community planners, designers, service providers and policy makers share a stake in understanding how older adults report adjusting attitudes to optimise ageing in place within the challenges of disruption and stress. Factors that older adults identify as supportive warrant consideration for how they may be targeted to enhance positivity towards ageing and quality of life for the rapidly growing population of older adults – both through the pandemic and beyond.

Background

People increasingly seek to optimise relationships with physical and social environments as they age (Lawton and Nahemow, Reference Lawton, Nahemow, Eisdorfer and Lawton1973; Golant, Reference Golant2015; Oswald and Wahl, Reference Oswald, Wahl, Rowles and Chaudhury2005; Iwarsson et al., Reference Iwarsson, Wahl, Nygren, Oswald, Sixsmith, Sixsmith, Szeman and Tomsone2007). An ecological framework focuses on person–environment fit (Lawton and Nahemow, Reference Lawton, Nahemow, Eisdorfer and Lawton1973), recognising that the interplay between environmental characteristics and personal competencies and preferences shape experiences of ageing. Place-based social, physical and technological characteristics address basic needs, such as safety and security, as well as cognitive and emotional needs, such as social connection and contribution (Kendig, Reference Kendig2003; Wahl and Lang, Reference Wahl and Lang2003). An array of factors are recognised at a micro- and macro-scale and include objective elements such as the design of homes, neighbourhoods and transportation networks; social and technological factors such as places for community gathering and access to resources; cultural, psychological and perceptual factors likewise shape person–environment dynamics (Wahl and Weisman, Reference Wahl and Weisman2003). Complementary to factors that shape person–environment fit, Rowles’ concept of ‘autobiographical insideness’ recognises that memories support a sense of place identity and shape people’s feelings about where they live (Rowles, Reference Rowles, Rowles and Ohta1983). Internal factors such as self-concept, emotions and belief systems play into the dynamics between people and places, and inform habits, routines and self-defining activities, which in turn integrate with cognitive processes of person–environment exchange such as attitudes and evaluations (Rowles et al., Reference Rowles, Oswald, Hunter, Wahl, Scheidt and Windley2004). Self-defined meanings of ageing in place affirm environmental factors that contribute to independence and autonomy, as well as social factors that sustain relationships and roles (Wiles et al., Reference Wiles, Leibing, Guberman, Reeve and Allen2012).

Ageing in place, or ‘being able to remain in one’s current residence even when faced with increased need for support because of life changes’ (Greenfield, Reference Greenfield2012: 1), acknowledges the highly dynamic nature of relationships between people and place. Adaptation is integral to ageing in place as external and internal factors change over time. Literature suggests person–environment development intensifies during times of significant ecological transition (Wahl et al., Reference Wahl, Iwarsson and Oswald2012). The concept of residential normalcy emphasises change over time as places provide a comfort zone of environmental mastery that is unique to the abilities, lifestyles and preferences of individuals (Golant, Reference Golant2011, Reference Golant2015). Adjusting to changes in external and internal factors influences how people function within environments which, in turn, plays a role in how people feel about the places where they live (Chaudhury and Oswald, Reference Chaudhury and Oswald2019). Ageing in place can thus be addressed as an ambivalent concept that incorporates both positive and negative effects to health and wellbeing associated with autonomous living.

The ecological framework creates a critical lens for examining ageing in place during the conditions of the pandemic. The public health crisis created environmental uncertainty, disruption and various threats in a relatively short period of time. In response, environmental stressors such as physical distancing restrictions, stay-at-home orders and restricted access to community have impacted people with likely long-term negative mental health effects (American Psychological Association, 2021). The loss of interpersonal connections and limited access to resources (such as community and recreational centres) are attributed to negative health outcomes for people of all ages (Devine-Wright et al., Reference Devine-Wright, de Carvalho, Di Masso, Lewicka, Manzo and Williams2020). External stressors include greater social isolation, enhanced economic risk and delayed medical treatment (Miller, Reference Miller2020). Older adults are also impacted by the ‘digital divide’ or ‘grey divide’, referring to limitations in digital literacy and access, meaning older adults may benefit less from digital measures put in place to help close the gap in isolation measures (Sixsmith, Reference Sixsmith2020; Van Jaarsveld, Reference Van Jaarsveld2020). Collectively, pandemic-related stressors are known to affect physical, social and personal domains directly and indirectly, and often in detrimental ways (Pietrabissa and Simpson, Reference Pietrabissa and Simpson2020).

Place attachment, or the emotional bond between a person and place, is an affective relationship known to have a buffering effect on stress for older adults (Rowles and Bernard, Reference Rowles and Bernard2013; Oswald and Konopik, Reference Oswald and Konopik2015). Literature indicates that place attachment may help alleviate the stress of home confinement during the pandemic for some people, as it reinforces connections to social and physical aspects of the home (Meagher and Cheadle, Reference Meagher and Cheadle2020). Yet, in the context of the pandemic, literature also shows that home environments have increasingly become sites of mental health crises, including self-harm and suicide ideation (Olding et al., Reference Olding, Zisman, Olding and Fan2021). Feelings of ‘partial institutionalisation’ are reported due to confinement in home environments (Armitage and Nellums, Reference Armitage and Nellums2020), and there has been an increase in health-harming behaviours inside the home such as excessive alcohol consumption, poor diet and lack of exercise. Reports of domestic violence and elder abuse are additional concerns that have spiked during the pandemic (Taub, Reference Taubapril 6, 2020).

Within the context of these external and internal pressures, literature points to coping mechanisms that lend insight into why older adults may fare better than other age groups in terms of behavioural and mental health (García-Portilla et al., Reference García-Portilla, de la Fuente Tomás, Bobes-Bascarán, Jiménez Treviño, Zurrón Madera, Suárez Álvarez, Menéndez Miranda, García Álvarez, Sáiz Martínez and Bobes2021; Sterina et al., Reference Sterina, Hermida, Gerberi and Lapid2022). Stress levels and anxiety associated with contracting COVID-19 are found to be similar among all age groups, yet older adults more frequently engage in proactive coping (Pearman et al., Reference Pearman, Hughes, Smith and Neupert2021) and prosocial activity (Sin et al., Reference Sin, Klaiber, Wen and DeLongis2021) than younger adults, which is associated with improved daily affect and social wellbeing. Older adults report a higher sense of personal cost associated with contracting COVID-19, but less personal cost in daily life due to the pandemic (Jin et al., Reference Jin, Balliet, Romano, Spadaro, van Lissa, Agostini, Bélanger, Gützkow, Kreienkamp and Leander2021). Findings show older adults’ expectations regarding ageing are far less negatively impacted by the pandemic than those expectations among younger adults (Whatley et al., Reference Whatley, Siegel, Schwartz, Silaj and Castel2020), suggesting greater resiliency and ability to make lifestyle changes necessary to maintaining wellbeing. Literature that affirms psychological coping and adaptability among older adults during the pandemic points to the need to better understand pathways for coping with crisis (Fuller and Huseth-Zosel, Reference Fuller and Huseth-Zosel2021).

Given the recency and ongoing nature of the pandemic, there is limited understanding of how older adults have adjusted attitudes to ageing and relationships to place through the challenges of the pandemic (Weil, Reference Weil2021; Leontowitsch et al., Reference Leontowitsch, Oswald, Schall and Pantelin press). This is critical to explore, not just as a counternarrative to pervasive negative stigmas about ageing, but also to further understand the relationship between environments, ageing and change under adverse conditions. Thus, we examined the research question:

• How has the pandemic influenced attitudes about ageing in place among community-dwelling older adults?

Qualitative data in this study provide insight into ways older adults reported shifts in attitudes and behaviours in the places they live in order to sustain positive outlooks to ageing in place.

Methods

This study used photovoice to elicit audio and visual data. Photovoice (Wang and Burris, Reference Wang and Burris1994, Reference Wang and Burris1997) is a participatory action research method that allows individuals to document their experiences through photography. The method has been used to elicit critical dialogue about ageing-related issues (Mahmood et al., Reference Mahmood, Chaudhury, Michael, Campo, Hay and Sarte2012; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Buys and Donoghue2019). Photovoice involves participants taking photographs of meaningful places or objects, recording details about each place or object, and discussing photographs with researchers to identify salient issues and themes (Novak, Reference Novak2010; Plunkett et al., Reference Plunkett, Leipert and Ray2013). This method allows researchers to visualise perceptions and narratives of everyday realities and allows participants to share knowledge about complex issues that might be otherwise difficult to discuss (Novak, Reference Novak2010). Photovoice also enables the representation of broad experiences and has been used to understand qualitatively environmental factors that support conceptualisations of healthy ageing in place (Kohon and Carder, Reference Kohon and Carder2014; Chan et al., Reference Chan, Chan, Chan, Cheung and Lee2016; Van Hees et al., Reference Van Hees, Horstman, Jansen and Ruwaard2017; Ronzi et al., Reference Ronzi, Orton, Buckner, Bruce and Pope2020). Photographic representation allows for components of ageing, such as feelings of apprehension or reassurance when ageing in place, to be understood through the first-hand experiences of participants. This data collection method allows researchers to understand a myriad of experiences and perspectives, and to gain insight into opportunities that support social participation and engagement (Bai, Reference Bai, Lai and Liu2020).

Recruitment

Participants were recruited from the Salt Lake City metropolitan area through informational flyers that were distributed electronically and via mail through databases maintained by ageing services organisations; additionally, flyers were printed and posted in common areas of independent senior living residential towers. Flyers indicated information which interested individuals used to contact the research team. Individuals were eligible for participation if they were aged 70–85, living independently and fluent in English. Institutional Review Board approval at the University of Utah was obtained for this study. All participants understood that engagement in the study was voluntary, and they could discontinue participation at any time.

Data collection

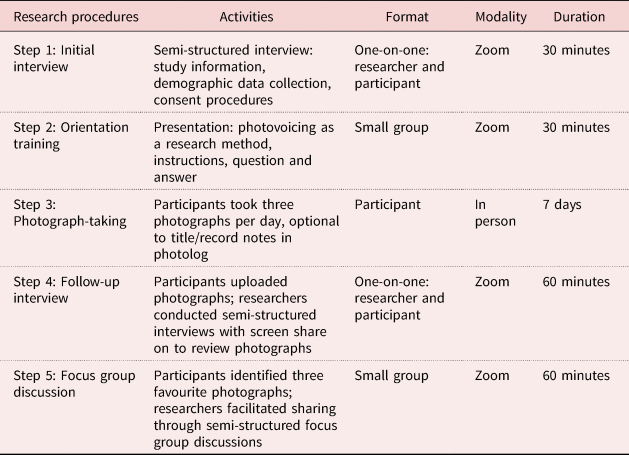

Researchers conducted a 30-minute screening session with participants individually, wherein demographic data were collected. A Waiver of Informed Consent was presented which allowed participants to provide verbal consent to participate in the study and waive the requirement of a signed document. Small-group orientation sessions over Zoom, a video conference platform, were then conducted to introduce the photovoice method. Participants were asked to take three photographs per day for the duration of one week. Disposable digital cameras were offered to participants but all chose to use their personal cell phone cameras to take pictures. Additionally, participants were asked to record information daily in a logbook about the photographs they took, including the date of the photograph, the place it was taken and a ‘title’ to photographs to help capture meaning. After one-week of participant photograph collection, a researcher conducted a one-on-one semi-structured interview to gain an understanding of the stories and personal meanings of the images. Researchers asked a series of questions to prompt participants to reflectively share information, including (a) Can you tell me what we are seeing in this photo?; (b) What does this photo mean to you about ageing in place?; and (c) How did the pandemic impact the way you see this? Visual analysis of photographs was further supported by discussing the significance of the title that participants gave to each photograph. Participants were then asked to select three photographs that best represented their ideas about ageing in place during the pandemic and present them in a small focus group. Researchers facilitated participant-led discussions of key photographs and meanings to ageing in place during the pandemic in small focus groups, again utilising visual data as forebear to narrative data. Table 1 summarises photovoice data collection procedures and modality. All meetings were conducted over Zoom, and were recorded, transcribed and checked for accuracy. Data were made anonymous by assigning participants an identification number. Data collection occurred from May until July 2021. All participants except for one completed the full study. Upon completion of data collection, participants were compensated with a US $75 gift card.

Table 1. Photovoice study procedures with research participants

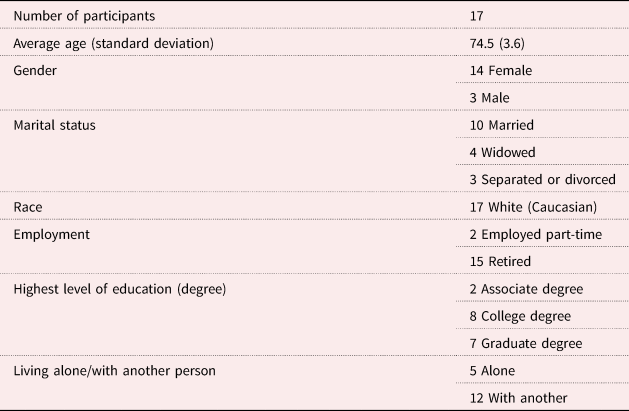

Seventeen community-dwelling adults aged 70–85, with an average age of 74, were recruited (Table 2). The majority of participants were women who lived with another person; all were Caucasian with post-secondary education. Thematic analysis led to the creation of five themes that describe the ways participants reported shifts in how they valued ageing in place during the pandemic.

Table 2. Study participant demographics

Data analysis

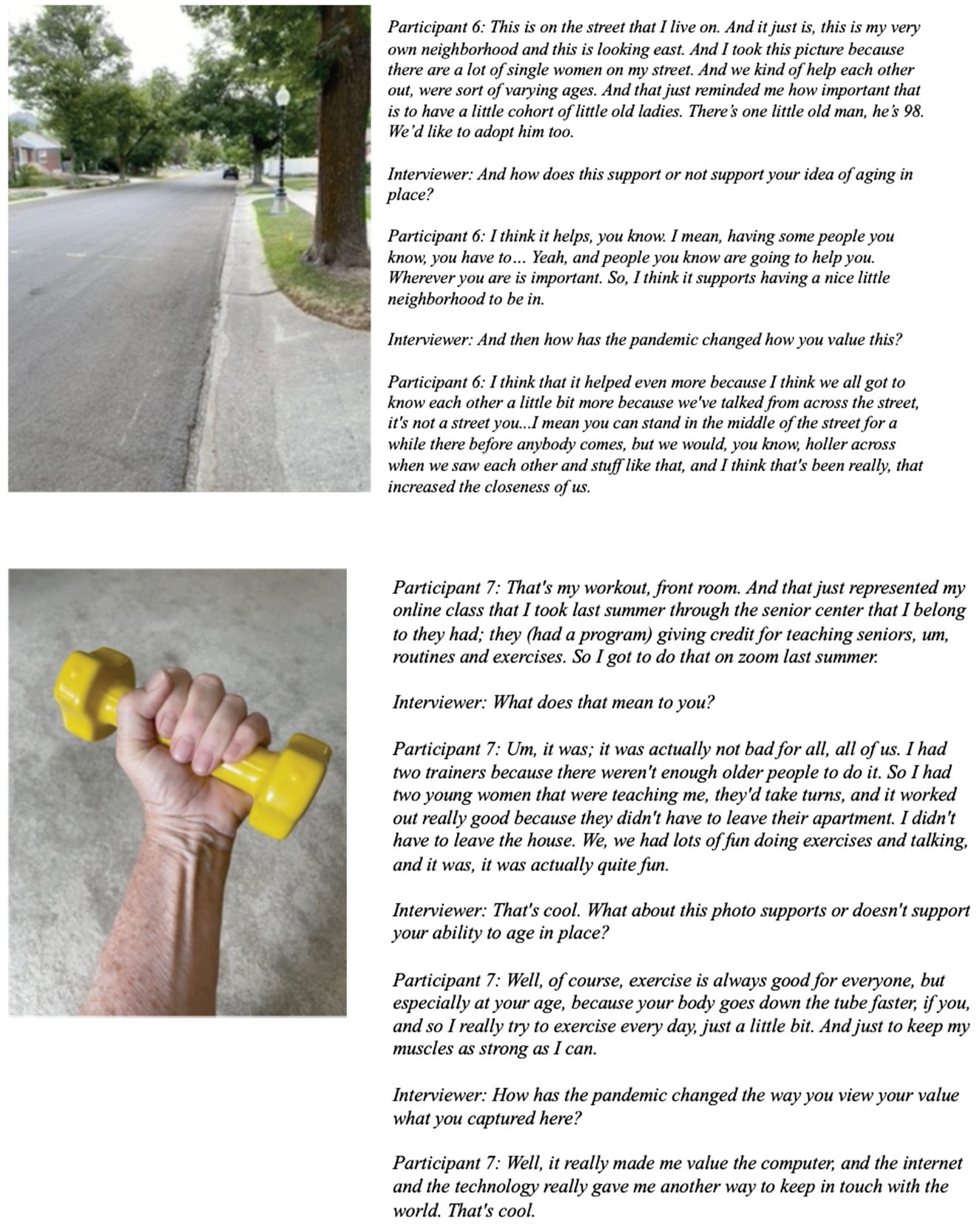

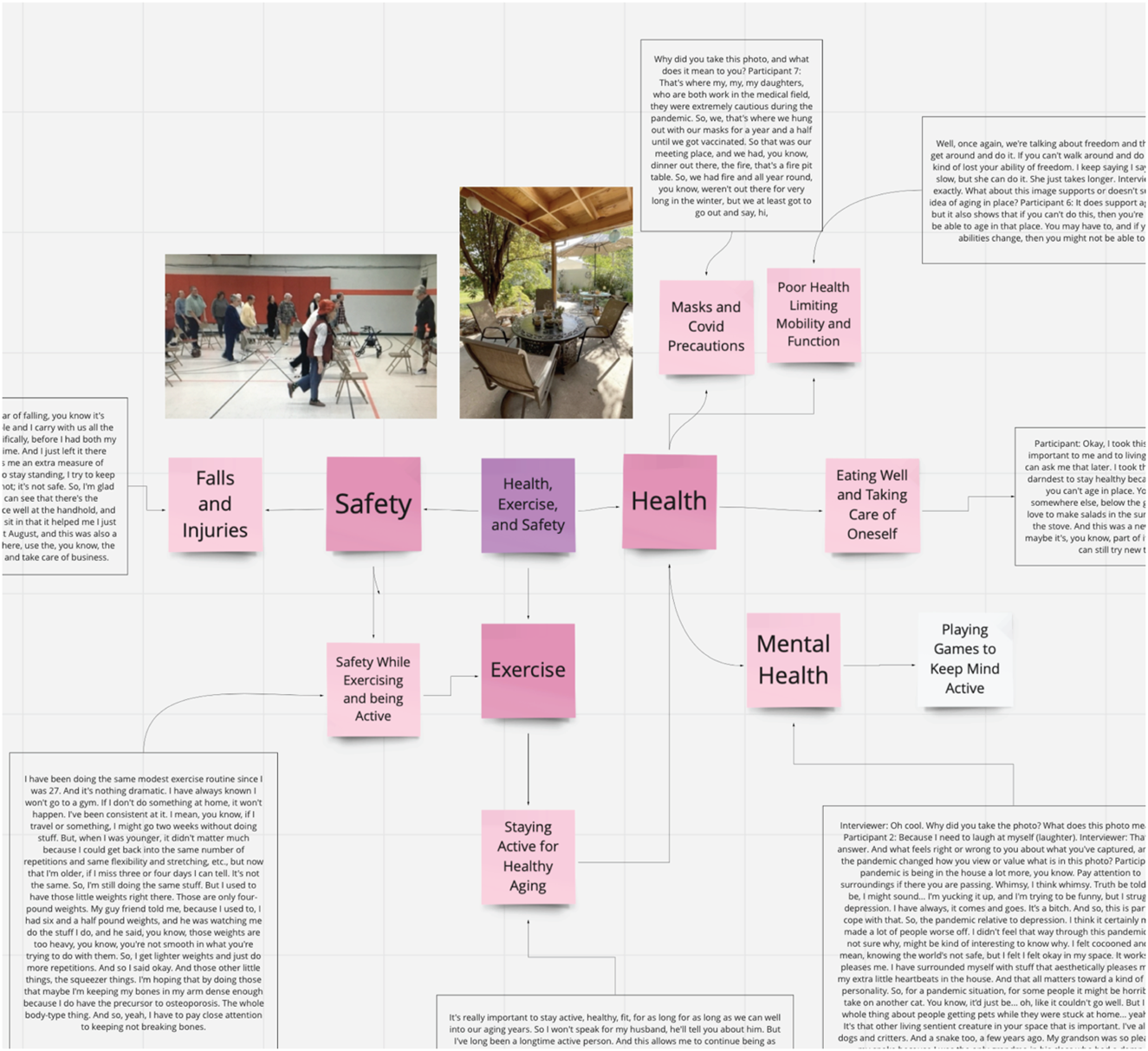

Researchers worked in several phases to analyse data thematically and identify central concepts (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). Familiarisation with data was ensured through reading transcripts and listening to audio-recordings. The team of faculty investigators and research assistants identified an initial set of codes, and a pair of research assistants independently coded transcripts using NVivo 12. Codes were cross-read and discussed by the research team. Patterns and nuance in the data led to a larger, more detailed data codebook that was developed by the research team. Codes were visually mapped on Miro – an online whiteboard – and grouped into preliminary themes. Sample quotes and photographs were included on the Miro-based mapping to support the process of reviewing codes and identifying themes. Figure 1 illustrates examples of photographs and interview transcript excepts. The research team reviewed and discussed the visually mapped data, and distinguished primary categories of coded data. Collectively, the team defined and named themes within the overall categories, utilising Miro as a visual organisation tool. Figure 2 illustrates an example of an early mapping of data into categories utilising Miro. The process of writing and reviewing definitions, and revisiting data extracts on Miro, supported the iterative nature of discerning layers of meaning and identifying crossover between themes.

Figure 1. Sample of photographs and interview transcripts.

Figure 2. Example of initial mapping of categories on Miro board.

Data saturation was found during the analysis based on repetition of themes and overlap of characteristics within categories (Morse, Reference Morse2015). Themes that were explored in individual interviews between participants and researchers re-emerged in the small-group discussions, and this further supported indication of data saturation in the analysis. Qualitative rigour was applied through analyst triangulation as the research team discussed themes and coding structure until consensus was reached (Creswell and Miller, Reference Creswell and Miller2000; Barusch et al., Reference Barusch, Gringeri and George2011).

Results

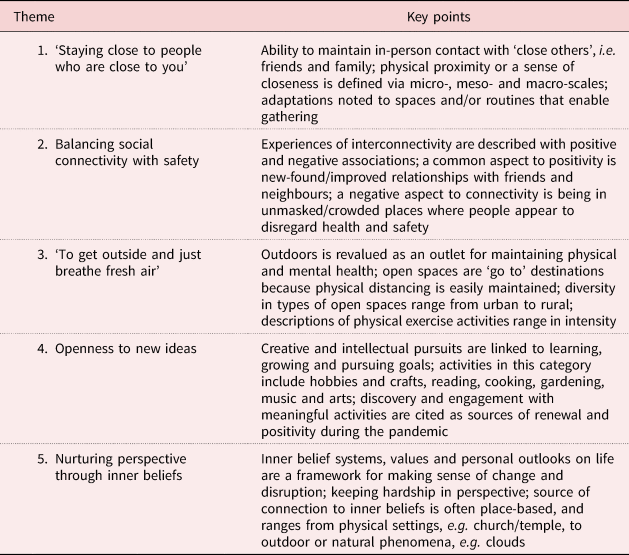

Table 3 summarises the themes.

Table 3. Coding and thematic analysis

Theme 1: ‘Staying close to people who are close to you’ – place as shared physical proximity

Physical proximity to family and loved ones was identified by nearly all participants as a critical environmental and social factor that had been important to them prior to the pandemic, yet had become even more significant since the onset of pandemic response measures, particularly in shaping positive attitudes towards ageing in place. Participants described how restrictions to socialising and in-person gathering impacted their ability to visit loved ones. For instance, describing a photograph of a child’s face mask hanging on a cabinet door, a participant reflects:

This was just about staying close to people who are close to you, which I think is really important in general as you get older and … was particularly important in the pandemic. There’s only a handful of people you ever see. And this little five-year-old [the participant’s granddaughter] was one of the most important for sure. (Participant 17, age 71, male)

The significance of the granddaughter’s mask resonates with the sentiments of other participants who shared personal belongings around their homes that recall the physical presence and proximity of loved ones, illustrating the value of small personal objects in satisfying the desire to maintain contact with loved ones within the confines of the pandemic.

Participants reported adapting places around their home to facilitate ‘staying close’ with their families through the pandemic. Reflecting on a photograph of a table and chairs arranged on a backyard patio, a participant described:

That’s where my daughters [and I] hung out with our masks for a year-and-a-half until we got vaccinated. So that was our meeting place, and we had dinner out there … we had [a] fire and we weren’t out there for very long in the winter, but we at least got to go out and say, hi. (Participant 7, age 71, female)

The physical adaption of space was accompanied by an adjustment to expectations in order to preserve the ritual of gathering – which the participant and her daughters prioritised over the discomfort of cold weather.

The importance of close physical proximity is further understood through the dimension of revaluing home location. A participant described how she had contemplated moving out of state after retiring and prior to the pandemic, but chose to remain living near her two children. A photograph she took of her house signifies the following:

This matters, I think, in the broad sense of pandemic because when I bought the house … I still felt a very young middle age. It was like, you know what, a little nice to be close [to my children]. I can take care of her dog, she can take care of my critters. But as I’m old – and this is new for me to even talk this way – it matters … Older people want to be near family. I never really got it, that it was as important as it is. So, yeah, we all value it. (Participant 2, age 77, female)

The importance of living close to her children solidified over time, and the self-reflection captured in the remark ‘this is new for me to even talk this way’ indicates appreciation of this new attitude, potentially catalysed by the pandemic.

Collectively, these examples point to ways participants value physical proximity to loved ones throughout the pandemic and suggest the importance of maintaining intergenerational connections; as one participant reflects:

contact with young people is just one of the healthiest things we can do … during the pandemic … I particularly appreciate it now. (Participant 9, age 77, female)

Here an appreciation for physical contact with family members from younger generations characterises an aspect of ageing in place that is especially valued.

Theme 2: Balancing social connectivity with safety – place as safe social space

Participants described attempts to balance social connection with friends, acquaintances and fellow community members while navigating restrictions required to stay safe from COVID-19 infection. Attitudes towards sharing social spaces ranged from comfort and reassurance to frustration and anger, depending on personal perceptions of safety and security. For instance, a participant who self-described herself as ‘a loner’ stated, ‘I realised, actually, during COVID, that I do need people a lot more than I thought I did’ (participant 1, age 79, female). She described looking forward to rejoining group exercise classes in her residential building, noting ‘I didn’t realise how reliant I was on those classes’, yet also shares anxieties about living in close proximity with others:

I live in a 16-storey building with elevators and a shared laundry room. During the pandemic, the laundry room and the elevators were the scariest place to be because not everybody would wear masks … I got mad at a lot of people. (Participant 1, age 79, female)

This mix of emotions – from an appreciation for community to anger at others for not complying with health precautions – illuminates the conflict older adults can have balancing social connectivity while maintaining boundaries within which to feel safe.

Related to this, participants described how social isolation led to the revaluation of casual encounters with neighbours and acquaintances. Photographs captured acts of kindness and care, such as neighbours dropping off groceries or helping with home maintenance. Several participants described the strengthening of relationships as a result of the pandemic. A participant explained a photograph of her front porch in these terms:

I sit there in the morning and, actually, I read my phone. I used to read the newspaper, but now I read my phone and listen to birds and say hi to neighbours … What this did during the pandemic is I could connect with neighbours, and we could be safe while we were doing it. (Participant 6, age 73, female)

This resonates with the way another participant described her bond with women her age who live on her block:

We kind of get together to help each other. We talk. During the pandemic, we were hollering across the street to each other. It was great. (Participant 16, age 72, female)

There is a quality of reciprocity in these descriptions, suggesting that participants and neighbours value staying connected while keeping boundaries to safeguard health.

Theme 3: ‘To get outside and just breathe fresh air’ – place as connection to nature

Living in the geographic region of Salt Lake Valley, which has access to many outdoor amenities, participants described renewed appreciation for the outdoors as influential in their decisions about ageing in place. Participants reported spending more time outdoors during the pandemic because they had significantly more free time, and because ‘people were very cautious about walking clear out around each other’ (participant 3, age 70, female). Lack of other options for exercise and physical activity also factored into spending more time outdoors. A participant stated:

Access to the outdoors … became even more important under those circumstances where people were so limited in terms of options. I feel like it reinforced that appreciation for our access to outdoor physical activity. (Participant 17, age 71, male)

Participants associated spending time outdoors with improved mental and physical health. Commenting on a photograph taken on a daily walk through her neighbourhood, a participant said:

I want to walk in some place that raises my spirits, as well as keeps me healthy from walking … especially when isolation gets too much. (Participant 1, age 79, female)

Another participant photographed bicycles he and his wife were preparing to ride, saying:

We like to bike and during the COVID, it was the only activity we could do safely and on our own outdoors … and so we continued to do that in an effort to stay healthy and enjoy our larger community and what it provides. (Participant 11, age 71, female)

Photographs and stories reflected a diversity in outdoor environments appreciated by participants, depicting urban, suburban and rural spaces that ranged from small, intimate settings to large, open landscapes with diverse vegetation and typography. For instance, a participant noted that he and his wife ‘feel fortunate [for the] diversity in our outdoor experiences’ (participant 11, age 71, female). In addition to accounts of physical exercise, such as biking, hiking and walking, participants described a diversity of activities, such as birding, gardening and people watching, that were valued elements of their outdoor experiences.

Finally, participants identified how being outdoors facilitates companionship and connection to nature, humans and animals. One participant described her involvement with her local community garden as a way of staying connected to the outdoors, plants and fellow gardeners. Yet another participant described her love of tending her backyard garden, calling it ‘a plant companion’. Speaking to the importance of sharing experiences outdoors, a participant describes a photograph she took of two people standing six-feet apart at a trailhead, saying:

The point of this one was to reinforce how important this is to include others, including, if you have them, pets and dogs in particular … And that would also extend to friends and acquaintances that you might be hiking with as well. So, that’s meant to be complementing the activity in general by having other living creatures do it with you. (Participant 3, age 70, female)

Routine dog walks were found as a source of positivity; describing a close-up photograph of two dogs, a participant said:

We’re on a dog walk. I love the dogs. I love being able to walk. I walked all during COVID, and this was a wonderful time. (Participant 5, age 72, female)

Participants in our study who lived alone were more likely to have a pet (three out of seven) than those were who lived with other people (three out of ten).

Theme 4: Openness to new ideas – place as new platforms for learning

An essential element of ageing in place that participants described in the context of the pandemic was the heightened appreciation for pursuing hobbies and goals and learning new things. Participants attributed having more time during the pandemic to dedicate to activities of interest and described opening up to new ideas in various ways, including learning Spanish, studying origami and reading more about world history. For instance, one participant took a photograph of a ukulele saying:

The reason I got the ukulele is because of the pandemic and being trapped at home and wanting to not waste that time we were given. So, I decided to try to learn something new. (Participant 3, age 70, female)

Another participant photographed a series of bird books stacked on a windowsill, saying:

I just had more time, so I got more books and did more research, and took more classes on birding … it’s a good pandemic activity because the birds really don’t care. (Participant 7, age 71, female)

Technology was also reported to play a role in keeping participants engaged in meaningful activities, though there were mixed reviews about online learning environments. Identifying the benefits of online classes, one participant said:

It’s the one part of the pandemic that, to be honest, I liked because I was able to take more classes. Whereas before, I had to think of the time taken to get there and the money, and I’d had to work around the other schedules; whereas this time, I could take whatever. I could just schedule it, and … they Zoom it. (Participant 6, age 73, female)

Other participants, however, reported decreasing participation in continuing education because online platforms did not resonate with them or because they were ‘just tired of Zoom’ (participant 13, age 77, female). While virtual learning environments received mixed reviews, hybrid platforms where an integration of in-person and digital platforms helps participants engage with hobbies and interests were generally well received. Examples of hybrid activities included having craft materials delivered to homes to support the curriculum of an online craft class, or synchronous film viewing with friends and loved ones. One participant reflected on checking out library books online and picking them up kerbside, saying:

It’s been huge for me when they started opening [the library] and at least bringing your books to your car … as we age, rather than just be selfish and spend all my time going out to lunch and dinner with friends, I need to study about things. I’ve loved it. So, in that regard, the pandemic for me was good. (Participant 14, age 74, female)

This reflects a shift in attitudes and behaviour towards hybrid engagement, and a revaluation of learning and exposure to new things as a beneficial aspect to ageing in place.

Theme 5: Nurturing perspective through inner beliefs – place inside the head and heart

A final theme focuses on personal values and perspectives, and the role that inner belief systems play in shaping attitudes on ageing in place. Participants described perspectives of their psychological or spiritual grounding that influenced how they interpreted and managed circumstances brought about by the pandemic. They identified sacred spaces that reminded them of their belief systems and shaped their outlook during the pandemic. For instance, one participant photographed a Buddhist altar that she created on her patio, saying:

I’m not a true Buddhist but I like their philosophies about life and death and transition, and constant change … it really helps me as I age … and [the Buddha statue] just reminds me to laugh and smile when things get weird, and [during the pandemic] they were pretty weird. (Participant 7, age 71, female)

Another participant photographed the interior of her church sanctuary titled ‘Empty Pews’. Describing the meaning of the photograph, the participant reported:

We were no longer able to go to Mass on Sunday, [but] I was able to still go to church and sit there in the presence of God and by myself, or with just one or two other people without risking getting COVID. (Participant 5, age 72, female)

Participants also photographed phenomena, such as cloud formations or waterfronts, that reminded them of personal axioms. For example, describing the meaning of a photograph of a large cloud, a participant said:

I was so excited to see a cloud with the drought. And it was looking good. But yeah, we are in interesting times. Pandemic, mega-drought … for anybody who’s been down to Mesa Verde and the Colorado Plateau where the Anasazi left, and had to go down further south into Rio Grande corridor … it was a drought that put them against each other, you know, they were all struggling to survive. We’ll see what happens with this one. So, in the broad scheme of things that cloud represents a lot … the cloud means to me, keep it in perspective. (Participant 2, age 77, female)

Similarly, another participant took a photograph that shows a convergence of streams and shared:

That’s the confluence right there … it supports my idea of ageing in place in that we all have … different pieces that make up life. And so, we create our own confluence. (Participant 16, age 72, female)

These data demonstrate how participants ascribe significant meanings to places and experiences in their daily environments that connect them to their beliefs and perspectives.

Discussion

This study explored how the pandemic influenced attitudes about ageing in place among community-dwelling older adults. Five themes were identified that reflect the value of physical closeness to family and loved ones, balancing social connectivity with safety, access to outdoor activities, opportunities to learn new things and the role of inner beliefs for ageing in place. Our results highlight dynamics between physical environments, social connections, personal attitudes and behaviours that older adults associate with positive experiences of ageing in place.

Findings forefront myriad ways that attitudes have been intertwined with physical places during the pandemic. Home and neighbourhood domains are central to the theme ‘staying close to people who are close to you’; diverse types of public open spaces are highlighted in the theme ‘to get outside and just breathe fresh air’. Collectively these experiences point to ways participants describe a revaluation of place during the pandemic. The significance of in-person experiences and place is supported by research showing that limited face-to-face interactions and fewer regular activities correlate with higher rates of loneliness among older adults (Frenkel-Yosef et al., Reference Frenkel-Yosef, Maytles and Shrira2020; Fullana et al., Reference Fullana, Hidalgo-Mazzei, Vieta and Radua2020). Literature indicates a top stressor during the pandemic for US adults aged 60 and older is confinement/restrictions (physical domain), while the most commonly reported source of joy/comfort is family/friend relationships (social domain) (Whitehead and Torossian, Reference Whitehead and Torossian2021). The need to balance connectivity with safety appears to inform attitudes towards the outdoors as a means of maintaining physical and mental wellness while also keeping socially distanced from others (Finlay et al., Reference Finlay, Kler, O’Shea, Eastman, Vinson and Kobayashi2021). Our participants reported the significance of intellectual, physical and creative engagement during the pandemic, and identified the importance of place to their goals of staying active.

The correlation between place, behaviours and expectations draws attention to the performative aspect of place which enacts protection and interaction (Karimah and Paramita, Reference Karimah and Paramita2020). Relationships between physical spaces, social behaviours and attitudes (or self-reported ways of thinking) suggest that place is far from being a static container or backdrop to ageing in place, but is instead an active ‘player’ in lived experiences. Conceptualising place within these social-constructivist terms in gerontological literature (Andrews et al., Reference Andrews, Evans and Wiles2013; Van Hees et al., Reference Van Hees, Wanka and Horstman2021) is supported in the current study by the various ways that participants describe the intersection of attitudes, behaviours and environments as both relational and performative. For instance, the range of emotions associated with balancing social connection with safety demonstrates how certain contexts for connecting with others (such as talking with neighbours from safe distances on sidewalks) yields positivity while other contexts (such as passing neighbours in a stairwell without masks) create a source of fear and vulnerability.

Findings bring attention to ‘third places’ or ‘sites of significance’ as informal destinations outside the home that are associated with positivity such as enhanced mood (Oldenburg and Brissett, Reference Oldenburg and Brissett1982; Oldenburg, Reference Oldenburg1999; Gardner, Reference Gardner2011). Increased appreciation for public outdoor spaces characterises a type of place-based attitude seen across themes in this study. Data suggest that participants found ways to engage in activities of personal meaning by physically relocating to outdoor settings. This is consistent with findings from the National Poll on Healthy Aging (Malani et al., Reference Malani, Kullgren, Solway, Nanda, Ibrahim, Singer and Kirch2021), indicating that the majority of older adults spent time outdoors at least a few times a week during the onset of the pandemic. The poll distinguishes between different types of outdoor spaces – from personal, such as balcony, patio, porch or yard, to public, such as gardens, parks or woods (Malani et al., Reference Malani, Kullgren, Solway, Nanda, Ibrahim, Singer and Kirch2021) – which create different contexts for activities. Expanding on the notion of ‘home as a refuge, community as a resource’ (Oswald et al., Reference Oswald, Jopp, Rott and Wahl2011), it may be that public parks and open spaces have become increasingly important as ‘third places’ during the pandemic, providing a destination outside the home and a site for social support. Adjusting behaviours to align with social distancing norms, e.g. reading the newspaper on the front porch in order to greet neighbours, underscores a revaluation of ‘third places’ as portals to social connectivity. Place additionally plays a significant role in the theme ‘nurturing perspective through inner beliefs’ as physical locations – which range from places of worship to outdoor environments – prompt participants to experience and articulate personal beliefs and outlooks.

Positive outlooks on ageing in place that were found in this study are strongly associated with prosocial behaviour. Defined as ‘behavior that benefits one or more other people’ (American Psychological Association, nd), prosocial behaviour is recognised in the literature as a powerful source of motivation among older adults to help future generations and society (Midlarsky et al., Reference Midlarsky, Kahana, Belser, Schroeder and Graziano2015; Sparrow et al., Reference Sparrow, Swirsky, Kudus and Spaniol2021; Cho et al., Reference Cho, Daley, Cunningham, Kensinger and Gutchess2022), and is linked to a sense of wellbeing (Sin et al., Reference Sin, Klaiber, Wen and DeLongis2021). Volunteerism, care for children and grandchildren, and actions to support friends and neighbours are examples of prosocial behaviour described by participants in all themes of this study. Prosocial behaviour here highlights the significance of intergenerational relationships, and reflects ways that participants expressed revaluing relationships with members of other generations. Prosocial behaviour has also been discussed in terms of taking precautionary measures to safeguard personal and public health during the pandemic, such as mask wearing (Han et al., Reference Han, Jang, Cho and Choi2021), and resonates with how participants discussed balancing social connectivity with safety precautions to prevent virus transmission.

Participants of this study described increasing their daily physical exercise during the pandemic, and spoke of a new appreciation for physical activity due to mental and physical health benefits. Pandemic-related disruptions, including restricted movement and separation from family and friends, may particularly impact physical activity levels and habits among older adults (Cunningham and O’Sullivan, Reference Cunningham and O’Sullivan2020). It has been noted that physical activity became one of the few reasons for venturing out of homes during the pandemic which was socially and civically permissible in most countries (Ghram et al., Reference Ghram, Briki, Mansoor, Al-Mohannadi, Lavie and Chamari2021). Literature cites exercising, going outdoors and modifying routines as stress-reducing, coping strategies among older adults (Finlay et al., Reference Finlay, Kler, O’Shea, Eastman, Vinson and Kobayashi2021; Whitehead and Torossian, Reference Whitehead and Torossian2021). Our study participants who reported a decline in physical activity commonly cited cancellation of in-person classes and lack of motivation to do in-home exercise. This resonates with the literature demonstrating that interruptions to regular exercise programmes correlate with increased sedentary behaviour among older adults during the pandemic (Markotegi et al., Reference Markotegi, Irazusta, Sanz and Rodriguez-Larrad2021).

Technology as a means to stay busy with hobbies and family/friend interactions is also associated with maintaining positive mindsets among community-dwelling older adults during the pandemic (Xie et al., Reference Xie, Shiroma, De Main, Davis, Fingerman and Danesh2021), and reflects the findings in this study. Positive associations are found among older adults who increased internet use during the pandemic for interpersonal communication and online errands (Nimrod, Reference Nimrod2020). The spectrum of ways that participants described adjusting behaviours to be physically and intellectually engaged points to a variety of ways of coping with pandemic-related restrictions, and a diversity of pathways that support positive feelings about ageing in place.

Findings collectively point to a need to expand the definition of place beyond traditional domains of home and neighbourhood. This expanded definition may include digital and online environments, rural and open spaces, and ‘third places’ outside the home (Lee and Tan, Reference Lee and Tan2019). Moreover, online environments that support social connectivity, learning and independence were found to be highly influential in shaping attitudes. The role of natural and open spaces presents as a supportive factor to active ageing. Study findings also point to places that support contribution and intergenerational engagement as potential sources of positivity. The plethora of adaptations underscores the need to broaden discourse on place to living environments forged in response to the pandemic.

Future research

Future research should continue to garner input from older adults, both in terms of how experiences of living through the pandemic alter views and how positive attitudes to ageing are supported (Harper, Reference Harper2020; Miller, Reference Miller2020). The complexity of pandemic-related change points to the usefulness of assessments such as the Person–Place Fit Measure for Older Adults (PPMF-OA) which works across multiple domains to gauge change from older adults’ perspective, and links research with policy (Weil, Reference Weil2021). Co-design approaches that engage older adults to adapt existing technologies and forge new platforms hold promise for increasing participation with online environments (Cosco et al., Reference Cosco, Fortuna, Wister, Riadi, Wagner and Sixsmith2021). Participatory-based community research methods are critical to eliciting voices and lived experiences that are often unheard or underrepresented in public and policy-making discourses. Photovoice is but one method that engages knowledge from older adults with critical dialogue on ageing and contributes to an understanding of the multi-dimensional and multi-directional dynamics between ageing and place. Given the literature that demonstrates how social interactions, psychosocial support and engagement among older adults have varied widely during the pandemic based on socio-economic status, race/ethnicity, walkability of neighbourhoods and socio-political diversity (Finlay et al., Reference Finlay, Kler, O’Shea, Eastman, Vinson and Kobayashi2021), future research should aim to investigate how ideas of ageing in place may have shifted for historically marginalised populations of older adults. Relocation and immigration are significant factors that should be considered as a dimension to examining ageing and place (Weil, Reference Weil2021). There is also a gap in the literature with regard to understanding what ageing in place means for older people experiencing homelessness or who are housing insecure (Walsh and Kaushik, Reference Walsh and Kaushik2021; Canham et al., Reference Canham, Weldrick, Sussman, Walsh and Mahmood2022). Finally, the meaning of home among people living with degenerative disorders requires further study (Andersson et al., Reference Andersson, Nilsson, Slaug, Oswald and Iwarsson2020).

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, study participants were highly homogeneous (mostly women and married, and all Caucasian with children), which limits our understanding of how the pandemic influenced reconceptualisation of ageing in place among ethnic and gender-diverse older adults. Second, all participants reported good health, post-secondary education, and were skilled in navigating Zoom meetings, photograph-taking and transmission, and email communications that were elements of study participation. While participants’ residential living environment varied from single family homes to apartments and townhomes, participants reported feeling housing secure and generally expressed positivity towards the places they lived. The percentage of participants living alone in this study (29%) is representative of the US national average (26%), yet this is significantly higher than in other parts of the world (Ausubel, Reference Ausubel2020) and there is not enough data in this study to determine how living alone might impact experiences of ageing in place during the pandemic (Fingerman et al., Reference Fingerman, Ng, Zhang, Britt, Colera, Birditt and Charles2021). Future research should aim to recruit a more diverse sample of older adults across varying household compositions and socio-economic groups who are both renters and homeowners.

Conclusion

Attitudes towards ageing in place during the COVID-19 pandemic reveal a pivotal moment for ageing research, garnering new knowledge through the lived experiences of older adults. Physical, social and digital environments play a critical role in shaping experiences and attitudes, and have the potential to empower positivity. Photographs and stories collected in this study underscore the dialectic between physical places, social connectivity and activities of meaning – and point to the characteristic of diversity as a core component to what participants value in their experiences. Multi-disciplinary work points to how views on ageing have an impact on individual and societal levels over the lifespan (Klusmann and Kornadt, Reference Klusmann and Kornadt2020). Frameworks for productive ageing that emphasise engagement and meaningful contribution (Hinterlong et al., Reference Hinterlong, Morrow-Howell and Sherraden2001) may have an especially critical role within the confines of the pandemic and beyond. Policy making that recognises the heterogeneity of older adults, and is guided by principles of protecting rights and freedoms, should be advanced to move the needle in public discourse and planning (Harper, Reference Harper2020). This article aims to contribute to a new narrative that emerges from the pandemic, recasting views on ageing that integrates knowledge gained from ‘lived experiences’ with discourse on ageing in place.

Acknowledgements

We respectfully acknowledge that the University of Utah is located on the traditional and ancestral homeland of the Shoshone, Paiute, Goshute and Ute Tribes. For contributions to this project, we would like to acknowledge research assistants Jessica Van Natter and Natalie Caylor. We would also like to thank our partner organisations for support of this project and the invaluable insight of study participants.

Financial support

This research was supported by the Research Incentive Seed Grant Program, sponsored by the Vice President for Research at the University of Utah.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical standards

Institutional Review Board approval at the University of Utah was obtained for this study (IRB#00141945).