Introduction

Multiple factors beyond disease-related symptoms are associated with quality of life and wellbeing among people living with dementia (Martyr et al., Reference Martyr, Nelis, Quinn, Wu, Lamont, Henderson, Clarke, Hindle, Thom, Jones, Morris, Rusted, Victor and Clare2018). Recent evidence demonstrates that psychological characteristics and health, physical fitness and health, social situation and resources, relationships, and ability to manage everyday life are all independently associated with quality of life and wellbeing for people with dementia (Clare et al., Reference Clare, Wu, Jones, Victor, Nelis, Martyr, Quinn, Litherland, Pickett, Hindle, Jones, Knapp, Kopelman, Morris, Rusted, Thom, Lamont, Henderson, Rippon and Hillman2019a). Within these domains, numerous factors important for quality of life and wellbeing of people with dementia could potentially be affected by the stringent social restrictions imposed during 2020 to counter the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, these restrictions could potentially increase levels of loneliness, anxiety and depression, reduce participation in social and cultural activities, and make it harder to manage everyday activities (Brown et al., Reference Brown, Kumar, Rajji, Pollock and Mulsant2020). The impact could be particularly acute for people with certain types of dementia, such as Parkinsonian dementias (Killen et al., Reference Killen, Olsen, McKeith, Thomas, O'Brien, Donaghy and Taylor2020) where the risk of infection is higher and depression more prevalent than in Alzheimer's dementia (Ballard et al., Reference Ballard, Holmes, McKeith, Neill, O'Brian, Cairns, Lantos, Perry, Ince and Perry1999). In one large telephone survey, carers of people with dementia in Italy described significantly increased levels of anxiety, depression and other indicators of distress, in nearly two-thirds of people with dementia living under quarantine (‘lockdown’) conditions (Cagnino et al., Reference Cagnino, Di Lorenzo, Marra, Bonanni, Cupidi, Laganà, Rubino, Vacca, Provero, Isella, Vanacore, Agosta, Appollonio, Caffarra, Pettenuzzo, Sambati, Quaranta, Guglielmi, Logroscino, Filippi, Tedeschi, Ferrarese, Rainero and Bruni2020). Another telephone survey reported a worsening of cognitive function, particularly memory and orientation, in one-third of people with dementia, with some also declining in functional ability (Canavelli et al., Reference Canavelli, Valetta, Toccaceli, Remoli, Sarti, Nuti, Sciancalepore, Ruberti, Cesari and Bruno2020).

The effects of impacts such as increased depression, loneliness and reduced social participation may not resolve immediately when restrictions are lifted and social contact is resumed, but rather could have significant long-term impacts. For example, while little is known about longitudinal influences on quality of life, recent evidence suggests that for people with dementia, greater levels of social isolation and loneliness at baseline contribute to poorer quality of life and wellbeing after a period of two years (Matthews, Reference Matthews, Gamble and Clare2020).

Similar concerns emerge when we consider the situation of carers of people with dementia. Again, a wide range of factors is associated with their quality of life and wellbeing (Farina et al., Reference Farina, Page, Daley, Brown, Bowling, Bassett, Livingston, Knapp, Murray and Banerjee2017). Recent evidence indicates that the domains of psychological characteristics and health, physical fitness and health, social situation and resources, and the experience of care-giving itself are all independently associated with quality of life for family carers (Clare et al., Reference Clare, Wu, Quinn, Jones, Victor, Nelis, Martyr, Litherland, Pickett, Hindle, Jones, Knapp, Kopelman, Morris, Rusted, Thom, Lamont, Henderson, Rippon and Hillman2019b). Changes in daily life resulting from COVID-19 restrictions could be expected to affect the quality of life and wellbeing of carers in similar ways to those identified above for people with dementia. In addition, co-resident carers might experience an increased sense of role captivity due to being confined to the home with the person for whom they provide care and unable to take a break from caring. Cagnino et al. (Reference Cagnino, Di Lorenzo, Marra, Bonanni, Cupidi, Laganà, Rubino, Vacca, Provero, Isella, Vanacore, Agosta, Appollonio, Caffarra, Pettenuzzo, Sambati, Quaranta, Guglielmi, Logroscino, Filippi, Tedeschi, Ferrarese, Rainero and Bruni2020) found that two-thirds of carers for people with dementia responding to their survey were experiencing stress-related symptoms while living under quarantine conditions. Increased stress could be attributable in part to the loss of usual support services and opportunities for respite (Giebel et al., Reference Giebel, Cannon, Hanna, Butchard, Eley, Gaughan, Komuravelli, Shenton, Callaghan, Tetlow, Limbert, Whittington, Rogers, Rajagopal, Ward, Shaw, Corcoran, Bennett and Gabbay2021). These individual effects are amplified within care-giving dyads as carer stress and experience of social restrictions are directly associated with poorer wellbeing for the person with dementia (Quinn et al., Reference Quinn, Nelis, Martyr, Morris, Victor and Clare2020), while depression in either the carer or the person with dementia is directly associated with poorer wellbeing in the other member of the dyad (Wu et al., Reference Wu and Clare2021).

It is important therefore to consider the impact of COVID-19 restrictions on people with dementia and carers, and how any negative effects might be mitigated, as it is evident that this is a long-lasting international issue. Stringent social restrictions to combat the spread of COVID-19 and prevent the National Health Service (NHS) of the United Kingdom (UK) from being overwhelmed, termed ‘lockdown’ measures, were introduced in England on 23 March 2020. The population was advised to ‘stay at home’ to avoid all unnecessary contact with others, to maintain at least 2 metres distance from others at all times and to wash hands regularly. Gatherings of more than two people in public were banned, and public events including weddings and funerals were cancelled. People were advised to work from home, and places of worship, schools, hospitality and non-essential retail were closed. Schools remained closed until 1 June and the hospitality sector and places of worship until 4 July, with reopening subject to strict conditions. From 4 July, two households of any size were also allowed to meet in any setting. Additional guidance was issued to people deemed clinically vulnerable to extreme outcomes if exposed to COVID-19 on 17 March 2020 in the form of a letter from the government advising them to ‘shield’, i.e. advised to stay at home apart from daily exercise or medical appointments, with only those helping with care needs being allowed to visit. This guidance was updated in June 2020 when people were advised they could leave their homes and meet one other person outdoors as long as strict social distancing was maintained. This ‘extremely vulnerable’ group included people with existing health conditions; although older people were at increased risk, not all were asked to ‘shield’, and having dementia in itself was not an indicator for shielding.

Understanding more about the experience of people with dementia and carers during this period, both the challenges they have faced and the ways in which they have tried to adapt will make it possible to identify solutions and resources that can help to support people through the expected longer-term period of social restrictions and physical distancing. Better understanding of the experience of people living with dementia is needed to inform supportive responses, and might be utilised to enhance preparedness for future pandemics in England and other countries should they occur. The aim of this study was to contribute to such endeavours by providing timely evidence about the challenges and difficulties faced by people with dementia and carers, as well as the internal and external resources that helped them to cope during the severe social restrictions imposed in England in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, and as restrictions were eased. Specific research questions were:

• What impact did the COVID-19 pandemic and associated social restrictions have on the everyday experience, functioning, and emotional, physical and social wellbeing of people living with dementia?

• How did carers view the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated social restrictions on their own everyday experience and emotional, physical and social wellbeing, and that of the person they cared for, as well as on the care-giving relationship?

• What internal and external resources did people with dementia and carers draw upon to manage any difficulties and what might help to reduce any negative impacts?

Method

Design

The IDEAL (Improving the Experience of Dementia and Enhancing Active Life) programme centres on a longitudinal cohort study following people with mild-to-moderate dementia living in the community and, where available, their primary carers, recruited through 29 NHS sites in Great Britain (Clare et al., Reference Clare, Nelis, Quinn, Martyr, Henderson, Hindle, Jones, Jones, Knapp, Kopelman, Morris, Pickett, Rusted, Savitch, Thom and Victor2014; Silarova et al., Reference Silarova, Nelis, Ashworth, Ballard, Biénkiewicz, Henderson, Hillman, Hindle, Hughes, Lamont, Litherland, Jones, Jones, Knapp, Kotting, Martyr, Matthews, Morris, Quinn, Regan, Rusted, van den Heuvel, Victor, Wu and Clare2018). IDEAL is registered with the UK Clinical Research Network (UKCRN number 16593). In response to the emergence of the pandemic, the IDEAL COVID-19 Dementia Initiative (IDEAL-CDI) was rapidly established in April 2020 as a sub-study of the IDEAL research programme. The aims were first to provide evidence-based advice for people with dementia and carers drawing on findings from the IDEAL programme, second to monitor social networks to identify issues and concerns being raised by people with dementia and carers that could be addressed through updating the evidence-based information, and third to develop methods for interviewing IDEAL participants by telephone and conduct interviews with cohort members to learn about their experiences and draw out recommendations about how they could best be supported during the pandemic. Here we report a qualitative analysis of data gathered through telephone interviews with people living with dementia and carers who were participants in the IDEAL cohort study about their experiences during the initial period of lockdown and later during emergence from lockdown.

Ethical issues

Ethical approval was obtained as an amendment to the IDEAL programme from the Wales Research Ethics Committee 5 on 7 May 2020. Health Research Authority and Health & Care Research Wales approval was issued on 10 May 2020.

All participants had taken part in IDEAL and had previously consented to be contacted for an interview. Face-to-face contact was prevented due to lockdown measures and so we gained approval to conduct all study procedures by telephone. Invitation letters and information sheets were written as scripts that could be read out to participants over the telephone, with written information that could be provided by email. Participants were given time to consider taking part and the opportunity to ask questions before providing verbal consent, which was digitally recorded. Only participants who had capacity to provide verbal informed consent were recruited.

The topic guide was developed in light of earlier findings from the IDEAL programme and in association with a range of stakeholders, including an advisory group of IDEAL programme researchers and the IDEAL programme involvement group of people with dementia and carers, known as the ALWAYs group. The topic guide helped the interviewer to balance talking about difficult aspects of restrictions with covering aspects that had been relatively easy or even beneficial in some way, and to guide the interview to a positive ending. The researcher had the skills and experience to divert the conversation or discontinue the interview if appropriate, and to direct people to further services if necessary. On one occasion, concern about the wellbeing of an interviewee led the researcher to direct the interviewee to a local source of support.

Participant recruitment

IDEAL cohort participants were recruited by NHS sites who identified eligible participants through UK NHS memory services and other specialist clinics, and by contacting other local volunteers registered online with ‘Join Dementia Research’ (https://www.joindementiaresearch.nihr.ac.uk/) between July 2014 and August 2016. Inclusion criteria were a clinical diagnosis of dementia, a Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score of 15 or above indicating moderate severity, and residing in the community. Exclusion criteria were the inability to provide informed consent, terminal illness and any known potential for home visits to pose a risk to researchers. Where possible, a family member or close friend (here referred to as a ‘carer’) was recruited to participate alongside the person with dementia and provided informant ratings on relevant measures. In the first phase of IDEAL (Clare et al., Reference Clare, Nelis, Quinn, Martyr, Henderson, Hindle, Jones, Jones, Knapp, Kopelman, Morris, Pickett, Rusted, Savitch, Thom and Victor2014), participants were assessed at three time-points one year apart. Time 1 (T1) data were collected over 24 months from 2014 to 2016, Time 2 (T2) data were collected from 2015 to 2017 and Time 3 (T3) data were collected from 2016 to 2018. The cohort comprised 1,537 people with dementia and 1,277 carers at T1, 1,189 people with dementia and 988 carers at T2, and 851 people with dementia and 759 carers at T3. In the second phase of IDEAL (IDEAL-2; Silarova et al., Reference Silarova, Nelis, Ashworth, Ballard, Biénkiewicz, Henderson, Hillman, Hindle, Hughes, Lamont, Litherland, Jones, Jones, Knapp, Kotting, Martyr, Matthews, Morris, Quinn, Regan, Rusted, van den Heuvel, Victor, Wu and Clare2018), three further follow-ups plus additional targeted recruitment were envisaged, with the first wave, Time 4 (T4), taking place two years after T3. At the time of the present study, assessments for T4, scheduled to run from 2018 to 2020, had been halted due to the COVID-19 pandemic, at which point 251 people with dementia and 230 carers from the original cohort had been seen, together with 202 newly enrolled people with dementia and 170 carers.

Inclusion criteria for the current study were (a) ongoing participation in the IDEAL programme and (b) capacity to give informed consent. People with dementia and carers who had previously indicated their willingness to be contacted about participating in semi-structured interviews for qualitative analysis were identified from IDEAL programme records. All participants lived in community settings in England and had mild or moderate dementia at the time of their recruitment to IDEAL. Of all those seen at T4, 282 people with dementia and 313 carers had consented to an in-depth interview, and a list of these was produced to be approached for this study. Convenience sampling was used to maximise the likelihood of reaching people in a variety of circumstances, recognising that these different circumstances may affect the way they responded to the experience of restrictive measures. The list of the people seen at T4 who had consented to an in-depth interview was generated from the database with address and contact details, gender, date of birth, living situation (alone or with others), dementia diagnosis, and a note of whether contact should be made direct to the person with dementia or via the primary carer. We selected people using the list to ensure we had representation of people from different geographical, rural and urban locations, younger and older age groups, males and females, and people living alone or with others, and aimed for half of all approaches to be made directly to the person with dementia and the remainder via the identified IDEAL family member or friend carer.

People with dementia and carers were contacted by telephone and invited to participate in IDEAL-CDI. Where the initial approach to the person with dementia was made via the carer, the researcher subsequently spoke to the person with dementia if the carer deemed it appropriate. Capacity to give informed consent on the part of the person with dementia was gauged during these initial phone calls. During the conversation, the researcher sought to establish that the participant understood the study information and was able to weigh it up and reach a decision about taking part. Following the initial phone call(s), the Participant Information Sheet (PIS) was emailed to the prospective interviewee at least 24 hours before consent was sought, and a follow-up phone call was made to answer any questions and take consent. Where prospective interviewees were unable or unwilling to receive the PIS via email, it was read out to them over the phone prior to seeking consent. Capacity to give informed consent was gauged again during this second round of phone calls, as above. Verbal consent was obtained via phone immediately before the phone interview took place, and was audio recorded.

Data collection

The initial round of semi-structured telephone interviews was conducted between 13 May 2020 and 23 June 2020, during a period of stringent lockdown measures. The majority of the interviews lasted around 30 minutes, with a range of 20–70 minutes, depending on time availability and answering style, and were audio-recorded. They were conversational in style, taking into account the style of engagement of each interviewee, including any effects associated with dementia such as difficulty in word-finding or losing the train of thought within sentences. The topic guide included four themes relating to the possible experience of COVID-19 restrictions:

• Negative impacts on daily routines, and the emotional and social consequences of restrictions.

• Coping strategies and support found to be helpful in mitigating negative impacts.

• Unmet needs and additional support that might have been helpful in mitigating negative impacts.

• Any positive impacts in terms of unexpected benefits.

The topic guide provided the core questions, and these could be covered in any order depending on the participant's responses, with prompts and follow-ups tailored accordingly. The topic guide for the initial interviews can be found in the online supplementary material.

Follow-up interviews

Follow-up data collection took place between 28 and 30 July 2020. At that time, lockdown measures had been eased significantly but shielding measures for people at greater risk remained in place. Follow-up interviews lasted between 25 and 45 minutes, with the majority around 30 minutes. The procedures for gauging capacity and obtaining informed consent were the same as those used for the initial interviews and the same conversational style was adopted. The broad topics to be covered were:

• Current general welfare and circumstances.

• Discussion of themes that had emerged from each interviewee's initial interview and any changes in issues previously raised – better, the same or worse.

• Availability and suitability of post-lockdown support.

As the interviewer focused on issues raised in the initial interview, the content and direction of the follow-up interview was personalised.

Data analysis

Our approach to data analysis followed coding procedures involving open, axial and selective coding (Strauss and Corbin, Reference Strauss and Corbin1990). Data analysis was assisted by the use of NVivo 12 software (QSR International, Melbourne). First, we sorted data into the topic areas defined by the interview topic guide and open coded within those topics, then we grouped open codes into axial codes to develop categories of experience, and moderating factors influencing the nature, intensity and effect of that experience. We transferred these categories to a tabulated data display to enable further refinement of categories and their interactions through the development of selective codes. From this, we were able to identify patterns that we interpreted as ‘levels of coping’ into which each case had the best fit. We were also able to identify some overarching themes from categories and effects that occurred with the greatest frequency and impact across the dataset as a whole. The same process was followed for both initial and follow-up interviews.

To enhance the reliability and trustworthiness of emerging findings, a second member of the research team (CP) independently listened to a random sample of interviews and made notes on the main topics and perceived level of coping. These were used to verify and refine the analysis. Key findings were reviewed with CP and a third member of the research team (LC), and discussed with members of the advisory group and ALWAYs group (Litherland et al., Reference Litherland, Burton, Cheeseman, Campbell, Hawkins, Hawkins, Oliver, Scott, Ward, Nelis, Quinn, Victor and Clare2018). In addition, emerging findings from the analysis of interview transcripts were triangulated with issues raised through monitoring three relevant online discussion forums:

• Dementia Diaries, https://dementiadiaries.org/.

• Alzheimer's Society Innovation Hub, https://innovationhub.alzheimers.org.uk/.

• Centre for Applied Dementia Studies Blog, https://blogs.brad.ac.uk/dementia/.

We extracted content posted by people living with dementia on these forums prior to the initial interviews and again prior to the follow-up interviews. We examined this content to identify overarching issues discussed and later compared these with the findings emerging from our interviews to check whether there were additional insights we should explore. The perspective gained from the online content allowed the analysis of the interviews to be framed within a broader experience of lockdown shared by other people living with dementia. This triangulation provided a further layer of context and understanding to corroborate and augment the interview evidence (Schwandt, Reference Schwandt2007).

Findings

Of the 282 people with dementia and 313 carers who had consented to be contacted, we attempted contact with 27 individuals during the stringent lockdown period. In five cases the person was uncontactable and three carers said the people they cared for lacked capacity to take part or would find it too onerous and declined to participate. The remainder agreed to participate. There was no noticeable difference in participants’ willingness to take part or to spend more or less time in the interview depending on whether the PIS was sent in advance or read out over the phone. We interviewed two couples (person with dementia and carer), one jointly and one separately, nine individuals with dementia, and nine carers of whom two were jointly supporting one person with dementia. Through these interviews, we gained information about 19 individuals with dementia, either from the person with dementia (11 in all) or from a carer, and the 11 carers we spoke to also described their own experiences of providing care. We stopped recruiting when no new categories of experience or moderating factors emerged from analysis of the last four transcripts.

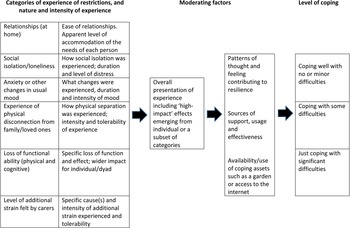

From the initial set of interviews, it was evident that the experience of restrictions was affected or influenced by a variety of moderating factors: relationships; social isolation and loneliness; anxiety; changes in mood; disconnection from family and loved ones; perceived loss of functional ability in both physical and cognitive domains; resilience; availability of support; availability of assets such as access to a garden or the internet; and carer strain. We considered participants’ experiences in terms of the number and extent of difficulties described, how problematic these were and what impact they had, and the presence or absence of moderating factors. These aspects were combined to provide an overall evaluation of level of coping.

We identified three groups of participants with dementia characterised by distinct levels of coping:

• Coping well with minor or no difficulties (N = 6).

• Coping with some difficulties (N = 6).

• Just coping with significant difficulties (N = 7).

It was noted that there did not appear to be a pattern in relation to MMSE score and level of coping. Figure 1 shows how the researchers interpreted the accounts of the experiences of restrictions to form levels of coping.

Figure 1. Conversion of categories of experience to levels of coping, showing the influence of moderating factors.

Table 1 shows the characteristics of participants grouped by the three levels of coping.

Table 1. Characteristics of the IDEAL COVID-19 Dementia Initiative (IDEAL-CDI) index participants grouped by level of coping

Notes: Data were retrieved from the IDEAL-2 cohort database from the last available time-point. Key to Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) score indicating degree of cognitive impairment: 21–30 mild; 11–20 moderate; 0–10 severe. 1. Person living with demention (PLWD) is co-resident carer for spouse who is also living with dementia. 2. Interviewed separately. 3. Interviewed together. 4. Lives with male carer for four days per week and with female carer for three days per week. 5. Primary and secondary carer interviewed. 6. Both primary and secondary carer are female. 7. Only the primary carer is co-resident with the PLWD. 8. Additional diagnosis of posterior cortical atrophy. 9. Interviewee is IDEAL consultee for PLWD. 10. Caring is shared amongst male and female family members.

For the follow-up interviews, resource constraints meant that we were unable to re-interview all participants. Therefore, we selected interviewees who were experiencing difficulties in coping or only just coping at the time of the initial interview, as this approach seemed likely to yield the most valuable information about support needs and effective ways of meeting them. All those invited agreed to be interviewed again. At follow-up we interviewed one couple (jointly), four individuals with dementia and one carer, gaining information about six people with dementia and two carers. This allowed us to explore changes in coping as restrictions were eased.

We first explore the accounts given by people with dementia and carers in each of the three categories to examine the impact of COVID-19 restrictions and describe how the follow-up interviews shed light on the changes in lived experience as the restrictions were lifted. Then we focus on views about the COVID-related information and support that was or was not forthcoming during this period.

Levels of coping

Coping well with minor or no difficulties

All six people with dementia in this category were living with others. Four of them did not identify a carer. All reflected co-resident relationships (mostly spousal) that did not appear to be strongly characterised by care-giving and receiving:

He is the one that does the … the cooking and does the shopping, so … and generally speaking, I do the … will look after the house and the garden. (CDI17, PLWD)

We haven't been affected that badly, actually, because I'm still going out and getting the shopping. [Name of PLWD]'s quite happy, he's been pottering in the garden and keeping himself busy. (CDI07, carer)

Some participants spoke about their accepting and positive attitude to overcoming difficulties, reflecting a capacity for optimism.

You know, we … we're just very realistic about the whole matter really, but that doesn't … it … there's no influence or reflection and having dementia. We just keep on as we have tried to all along … I, allowing for my age, and I recognise that at my age we are the most vulnerable section of community, I … I get sensitive to aches and pains or just feeling a little bit off-colour but I look to the heavens and say what do you think God, and we get over it. (CDI04, PLWD)

We take everything in our stride. That's the way we have always been. We've never met anybody that's got a relationship the same as us, we laugh at things … I do feel sorry for the people that have passed and their families because we have had some on the island where we live. But I don't know, I suppose I look at with my … my upbringing, people have to die for us to move on. (CDI07, carer)

Some participants with dementia drew on coping mechanisms they had employed on receiving the diagnosis of dementia to cope with COVID-19 restrictions in a similar way. Two spoke about continuing remote support from family (CDI04, PLWD; CDI18, PLWD), another continued practising memory strategies based on advice received at the time of diagnosis (CDI17, PLWD), and another reflected on managing fears at the time of receiving the dementia diagnosis:

Being told we had to shield … it was a bit like them telling us about, when … dementia, I mean. It's scary, no doubt about that … but we've tried not to be [scared] and to carry on sensibly with our lives. (CDI18, PLWD)

In addition, those demonstrating this level of coping appeared more likely to draw upon pre-existing neighbourhood and community support, and to derive some additional emotional benefit through any aspect of reciprocity that it contained:

Yeah, we get on with our neighbours but it's usually them that come to me for help … we've had a natter and … and I wave to people across the road as I'm walking the dog or whatever … So we've got quite a good neighbourhood, they're there if we need them. (CDI07, carer)

Coping with some difficulties

Those considered to be coping with difficulty described a greater sense of social isolation and disruption to everyday life than those who were coping well. Social isolation was often described in terms of being cut off from loved ones and the loss of physical contact, especially with grandchildren. This was sometimes linked with an awareness of ageing and the progression of dementia:

I mean we did go and visit our daughter in [town], her family, when I went up to the hospital there … so I have seen them all but … so we had a good laugh with them but not being able to give them a hug is terrible … And as you get older you … you think that your time for cuddling them is running out and you don't want to waste that time, really. (CDI05, carer)

Loss of contact and support from others within the ‘dementia community’ was also highly problematic for some:

I long to see my family and friends, I long to have the life I used to, be able to go out for coffee in the … the restaurants and meet with my peers at my dementia groups. (CDI12, PLWD)

Five of the six people with dementia in this category were aged under 75. Additionally, these people had a greater awareness of, and anxiety about, the risks associated with using public space which for some was rooted in actual experience of unfriendly incidents where people showed a lack of dementia awareness:

It's just … well, it's only recently that there's been quite a few people around now, so I've changed my time of walking because too many people have started being together without keeping … keeping separate… (CDI10, PLWD)

Carers also expressed fear about the person they cared for forgetting to observe social distancing and incurring social disapproval as a result:

She's certainly getting … she's more anxious … and more frightened. She's frightened that she … she won't obey the … the rules … obviously that she'll forget the rule … rules, of the six feet and things, and … not touch any other person. (CDI15, carer)

There was a noticeable turn in the interviews as the easing of restrictions was announced, with anxiety increasingly projected forward towards the ‘new normal’ and what it would mean for people living with dementia. This included mixed feelings about the temporary transfer of ‘physical’ services such as memory cafés and dementia support or advocacy meetings to online channels, and the possibility that online services would come to replace physical services post COVID-19 restrictions:

I am so grateful for that service because that has kept me going really, but it does … I do worry that it's too much sometimes and when things do start to change … with the virus getting less and that, we'll still be Zooming instead of meetings like before. (CDI12, PLWD)

Just coping with significant difficulties

Five of the seven participants categorised as ‘just coping’ lived alone. The remaining two lived with their spouses who were struggling to provide the level of care necessary to meet their needs. For the two co-resident carers, difficulties in the relationship with their spouses existed prior to COVID-19 restrictions. Increasing tension in the relationship was exacerbated by close confinement together and the lack of respite services, the need to take on caring tasks that had previously been undertaken by paid carers, and the additional pressure of enforcing COVID-19 restrictions with the person living with dementia:

…because I think of my life as a cage, then the cage has got smaller. (CDI01, carer)

…in my life just the two and a half hours … at the Memory Club on a Wednesday. Well, I can tell you, if you could see me now, the top of my head, right, I've got my skull and then my hair … well, my emotions are just trying to lift my skull up in a bubble, because I'm just … just imagine … just imagining to hold it all down. (CDI01, carer)

…they just say, ‘oh, you shouldn't try and explain; don't try and argue, just go along with it’, but I feel like screaming and saying, ‘When you're here 24/7’, you know, ‘you try it’. (CDI03, carer)

Disruption to the delivery of care such as daily administration of insulin treatment (CDI16, carer) was commonly, but not exclusively, associated with those considered to be ‘just coping’.

More generally, those who were living alone and ‘just coping’ described a more profound sense of social isolation:

Well, when I look out the window the trees seem to be … there are beautiful big green trees outside my window … and the trees seem to be in lockdown. Yes, there is nobody around. I look and wait … wait, I look for about five minutes and I don't see anybody. (CDI06, PLWD)

Two of these participants also reported dementia-related problems with cognition, particularly executive function, which they linked to the circumstances of COVID-19 restrictions:

I was all right for a couple of days, I managed quite well, but after that … I was getting very muddled, and I wasn't eating properly … I wasn't getting my food out in the mornings ready for the night-time meal, and I wasn't getting my washing done, or changing my clothes, or doing things like that. (CDI02, PLWD)

I go into sort of total confusion … But I found I was getting that [fog] more in my head. It used to be before the lockdown I had that feeling probably about once a month or every couple of months but then with the lockdown I was getting it every day and sometimes twice a day. (CDI14, PLWD)

While the use of outdoor space was important across all groups, all of those ‘just coping’ either did not have a garden or were unable to make use of their garden due to shielding or other issues:

So … so yeah, her mobility is less because she doesn't walk anywhere. I do, when I can, try and get her to walk up the garden but even that is, you know, difficult to be able to get her to go outside. (CDI16, carer)

Changes in levels of coping

The findings of the follow-up interviews revealed an improvement in coping for three of the six index participants (CDI02, CDI12, CDI14), but no change for the other three. One participant (CDI02) moved from just coping to coping well, one (CDI14) from just coping to coping with some difficulties, and one (CDI12) from coping with some difficulties to coping well.

Those who showed most improvement appeared to have taken greater advantage of the easing of restrictions and confronted their fears about venturing out:

It's got a lot better because I've decided I'm going to stop worrying about the … the virus, and just get on with my life, I've been going out and doing things, fully protected, of course … But I've decided it wasn't worth sitting indoors and worrying about it at my age, and with my condition. I thought I might as well enjoy what life I've got. (CDI02, PLWD)

I did feel like that until I actually got out to go to the hospital, and then when I got into the town, I … I know I wasn't supposed to do it, but I … I went … I went to Marks & Spencer's … I thought, ‘well, this … this seems okay’, and then I thought, ‘well, I can do this’. But then the next day, … I was actually fighting with myself to stay at home. (CDI14, PLWD)

I was in a bad place anyway, so my thinking was quite irrational. I don't know if I can cope any more. I had to really sort of have a word with myself and say right, we'll do baby steps here. And I can honestly say right now I'm in a good place. And as the world opens up, I see it as an adventure than a worry. I say, well, baby steps. Why don't you, you know, try to take a few steps out of your front door? … Out of your comfort zone. Just a little bit. And then the next day stay in. And I do it very gradually, you know? (CDI12, PLWD)

The easing of restrictions had a beneficial effect in all cases. Being reunited with families was a particularly welcome development:

When I used to get these like tormented feelings, I had an escape. Not now. Or not then. So it really did hit me hard. It really did hit me hard. It was actually Lifesize and Zoom meetings with dementia people. That's where I started to come out. And then I had a ‘bubble’ with my daughter. Seeing my daughter and hugging my grandchildren. And things like that. (CDI12, PLWD)

Just in the last week or two, you know, bearing in mind the COVID-19 thing, I have relaxed to the way I feel about it slightly, insomuch as we've met the family in the park on my husband's birthday, and had a bit of a picnic. (CDI01, carer)

Being reunited with family allowed the additional possibility of more support in helping some participants to return to greater normality:

At the moment, I'm down at my daughter's filling in time … and sort of going out, you know, places and doing things and gardening and so forth, seeing different places and that just, you know, being helpful … I must admit, instead of being, you know, in one place, giving me a … you know a relief from home, if you like. (CDI13, PLWD)

Reinstating a pre-restriction pattern of extended stays had helped to ease tensions in one interviewee's relationship with her husband, which had deteriorated during restrictions:

It was to sort of … put too much a finer point on it, it's to sort of a break away from my husband really … you know, because things … things would be fine, we'd be alright and then he would get sort of grumpy so it would make it, you know, worse on both sides of … you know, conflicting … sort of thing. (CDI13, PLWD)

However, in the one caring dyad where the least progress had been made, the key factor was a continuing high level of stress felt by the carer:

I'm fragile all the time. It's just I'm quite clever at putting a lid on it, but to be honest, if anybody said ‘boo’ to me, I'd … well, I'd end up, you know, in a huddle on the floor, if you know what I mean. (CDI01, carer)

COVID-related information needs

Among all participants and across the two time-points, there were mixed views about the quality and consistency of the general information about COVID-19 provided by the UK government through the daily televised briefing and other media sources:

I suppose what I've learnt more since coronavirus is to avoid … avoid things and it's also what … what I'm doing now is … is [inaudible] I can't … I suppose what I'm saying is I can't trust the news, or I don't understand the news… (CDI15, carer)

However, the prevailing view was one of concern about the lack of detailed information relating to their particular situation and that of their household:

That's why I registered as a [area] carer because I thought we might gain a bit of information that way. Do you think we should have known if I should have been shielding [name of PLWD]? I realise I could have asked somebody… (CDI10, carer)

Some interviewees did receive information they considered to be personalised in the form of text messages or letters, but most felt the content of information they received was unclear or contradictory. This was linked to the experience of discontinuity in contact with general practitioners and other primary health-care professionals such as district nurses, as people with health concerns were directed to call a central telephone number rather than contacting their primary care practice during the lockdown period:

I tell you one aspect which really I suspect what worried a lot of people, it certainly worried us, and that is that the kind of disappearance of the medical service providers … what I mean is these people were hard to come by. (CDI18, PLWD)

This appeared to be less of an issue at follow-up, with one follow-up interviewee reporting a definite improvement:

I … this … the last letter I've got, I can actually work on it; I can understand it. (CDI14, PLWD)

Support during restrictions

Twelve of the 19 participants spoke of the value of ‘just checking’ services during COVID-19 restrictions. Just checking services took the form of regular phone calls, weekly, fortnightly or monthly. Calls were mostly provided by voluntary organisations, such as the Alzheimer's Society, Carers UK or Age UK, and occasionally by NHS staff. The caller would ask how the person or couple were managing and engage in conversation, which could be purely social or could involve identifying and helping to meet support needs. The positive effect of these calls on those who received them was frequently mentioned. They were highly valued by interviewees regardless of their level of coping, and very effective in helping people to feel less alone in their difficulties:

…one of them will ring you, and say, ‘how's things going?’ and all of the rest of it, you know, and then if you've got any problems that come up during the conversation, you'll find someone will follow it up, and then ring you back, which all makes you feel good. (CDI01, carer)

Age Concern in [town], you know, we are … every … certainly every month we'll have a phone call from them saying, you know, are you okay, Mr [surname], is there anything we can do for you and whatever. (CDI04, PLWD)

Follow-up interviewees confirmed the continuing value and effectiveness of this type of support following the easing of restrictions.

Discussion

We interviewed people with dementia and carers during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic in England 2020 to understand the impact of severe social restrictions, and to identify resources that may help people with dementia to live well under similar circumstances in the future. Our qualitative analysis showed that some people with dementia were coping well, some with difficulty and some only just coping. Different levels of coping were experienced according to several factors. Positive social circumstances and previously developed coping strategies contributed to resilience for those coping well. Social isolation, anxiety, relationship tensions and withdrawal of practical support were prominent features for those coping less well. For some, it became easier to cope as restrictions were eased, whereas others experienced reduced confidence and concerns about COVID-19 risk. Regardless of how well they were coping, a lack of clear, straightforward personalised information relating to COVID-19 was of concern, while support in the form of regular ‘just checking’ phone calls were highly valued by those who received it. These findings both offer guidance on how to support people with dementia and carers through future periods of social restriction and contribute to our understanding of what makes it easier or harder to ‘live well’ with dementia. The evidence should inform policy and practice, and suggests approaches that could mitigate negative impacts during subsequent periods of restriction and gradual emergence from restrictions.

The varied experiences of coping conveyed in the accounts of people with dementia and carers in this study emphasise how unhelpful it is to consider people with dementia and carers as if they were a single homogeneous group. One positive message that emerges from our findings is that some people with dementia and carers were coping well. These individuals were generally in good psychological health, and had harmonious relationships and good community support, consistent with concepts of ‘living well’ that place social context and personal resilience in the foreground (Kitwood, Reference Kitwood1997; Bartlett et al., Reference Bartlett, Windemuth-Wolfson, Oliver and Dening2017; Austin, Reference Austin2018). Attitudes of optimism (Lamont et al., Reference Lamont, Quinn, Nelis, Martyr, Rusted, Hindle, Longdon and Clare2019, Reference Lamont, Nelis, Quinn, Martyr, Rippon, Kopelman, Hindle, Jones, Litherland and Clare2020), hope (Stoner et al., Reference Stoner, Orrell and Spector2018) and belief in one's ability to manage challenging situations (Dawson et al., Reference Dawson, Powers, Krestar, Yarry and Judge2013), despite the losses inherent in dementia, contribute to wellbeing for people with dementia and carers, and were evident among those coping well in our sample. Some participants explicitly mentioned applying coping strategies they had developed to deal with the impact of receiving a diagnosis of dementia to the current situation, reflecting the importance of wider dissemination of useful coping strategies and the potential for personal growth and transcendence (Wolverson et al., Reference Wolverson, Clarke and Moniz-Cook2016).

If social context and psychological resources are key to ‘living well’ with dementia, it follows that some people would face greater challenges in this area. For example, greater social deprivation is associated with poorer wellbeing and quality of life among people with dementia (Wu et al., Reference Wu, Clare, Jones, Martyr, Nelis, Quinn, Victor, Lamont and Rippon2018) and social isolation and lack of social support are linked to poorer wellbeing among carers (Zarit et al., Reference Zarit, Reever and Bach-Peterson1980; Pearlin et al., Reference Pearlin, Mullan, Semple and Marilyn1990; Au et al., Reference Au, Shardlow, Teng, Tsien and Chan2013). The social restrictions imposed during the COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent lifting of those restrictions demonstrates clearly how social context and circumstances, and the resulting practical and psychological impact, affect wellbeing. While the situation was universally challenging, the effects were exacerbated for groups facing particular issues, as our findings demonstrate. Rather than experiencing personal growth, our participants who were having difficulty coping were in effect struggling against further devaluation (Steeman et al., Reference Steeman, Godderis, Grypdonck, De Bal and Dierckx De Casterlé2007). Several surveys have documented increases in symptoms during similar COVID-19 restrictions among a significant proportion of people with dementia such as psychological distress (Giebel et al., Reference Giebel, Cannon, Hanna, Butchard, Eley, Gaughan, Komuravelli, Shenton, Callaghan, Tetlow, Limbert, Whittington, Rogers, Rajagopal, Ward, Shaw, Corcoran, Bennett and Gabbay2021; Manini et al., Reference Manini, Brambilla, Maggiore, Pomati and Pantoni2021), cognitive worsening (Canavelli et al., Reference Canavelli, Valetta, Toccaceli, Remoli, Sarti, Nuti, Sciancalepore, Ruberti, Cesari and Bruno2020), with impacts on communication and mood (Tsapanou et al., Reference Tsapanou, Papatriantafyllou, Yiannopoulou, Sali, Kalligerou, Ntanasi, Zoi, Margioti, Kamtsadeli, Hatzopoulou, Koustimpi, Zagka, Papageorgiou and Sakka2021) and falls (Barguilla et al., Reference Barguilla, Fernández-Lebrero, Estragués-Gázquez, García-Escobar, Navalpotro-Gómez, Manero, Puente-Periz, Roquer and Puig-Pijoan2020). Stress has been observed among a significant proportion of carers (Cagnino et al., Reference Cagnino, Di Lorenzo, Marra, Bonanni, Cupidi, Laganà, Rubino, Vacca, Provero, Isella, Vanacore, Agosta, Appollonio, Caffarra, Pettenuzzo, Sambati, Quaranta, Guglielmi, Logroscino, Filippi, Tedeschi, Ferrarese, Rainero and Bruni2020; Canavelli et al., Reference Canavelli, Valetta, Toccaceli, Remoli, Sarti, Nuti, Sciancalepore, Ruberti, Cesari and Bruno2020; Altieri and Santangelo, Reference Altieri and Santangelo2021). Qualitative studies can provide rich insights into the experiences that underlie these observations, such as feelings of separation, anxiety, exhaustion and loss of control resulting from withdrawal of social care and support services (Giebel et al., Reference Giebel, Cannon, Hanna, Butchard, Eley, Gaughan, Komuravelli, Shenton, Callaghan, Tetlow, Limbert, Whittington, Rogers, Rajagopal, Ward, Shaw, Corcoran, Bennett and Gabbay2021; Bacsu et al., Reference Bacsu, O'Connell, Cammer, Azizi, Grewal, Poole, Green, Sivananthan and Spiteri2021; Tolbot and Briggs, Reference Tolbot and Briggs2021). Our findings highlight emotions of loss, fear and loneliness among people with dementia, reflecting loss of contact, loss of skills, and anxiety about both coping with the current situation and returning to a more normal existence, while carers described feelings of frustration and in some cases desperation due to loss of services and support, and the resulting increase in demands and sources of stress. Concerns expressed about reduced ability to return to previously enjoyed services has been reported elsewhere (Giebel et al., Reference Giebel, Cannon, Hanna, Butchard, Eley, Gaughan, Komuravelli, Shenton, Callaghan, Tetlow, Limbert, Whittington, Rogers, Rajagopal, Ward, Shaw, Corcoran, Bennett and Gabbay2021; Tolbot and Briggs, Reference Tolbot and Briggs2021). For some, improvements were evident as circumstances began to change when restrictions were eased, reinforcing the link between social situation and ability to ‘live well’ with dementia. For others, the impact might be slower to resolve or might result in permanent losses or changes. In this sense, COVID-19 provides a natural demonstration of the social determinants of wellbeing for people with dementia and carers, and a reminder that modifications in these areas can potentially improve wellbeing.

With the likelihood of ongoing and sometimes stringent COVID-19 restrictions continuing for some time to come, our findings offer some insights about how people with dementia and carers might best be supported through these periods and how any longer-term impacts might be mitigated. First, the importance of regular ‘just checking’ phone calls cannot be overstated. The knowledge that someone cares enough to make a phone call, ask how you are and follow up on any urgent needs for support provides vital reassurance. These calls could also help to identify levels of coping. Beyond this basic level of community support, our findings show that needs vary, so identifying those who are having the greatest difficulty in coping would make it possible to target scarce resources and direct additional practical and emotional support where it is most needed. Our evidence indicates those who have fewer supportive relationships, experience anxiety or depression, are applying fewer coping strategies, or are reliant on external services or support should be prioritised. Where restrictions allow, opportunities for safe social contact and respite breaks for carers could be important priorities. Participants indicated they would value support in regaining functional skills that have declined due to lack of use, and restoration of access to familiar health and social care services. Support and services need to adapt and re-open in a COVID-19 safe way, whilst addressing the new challenges people with dementia have been facing.

We recognise that the study has some limitations. The sample size is small, although within the typical range for qualitative inquiry, and was limited by the time and resources available to contact and interview participants within the lockdown period. We contacted only a proportion of those potentially meeting inclusion criteria and therefore some different perspectives may have been missed, although there was a high degree of consistency in the issues emerging in the interviews and the online forums, alongside a clear picture of differing levels of coping in the interviews. The information we gained about the experiences of people with dementia was provided in some cases by the carer and, similarly, some people with dementia commented on the experiences of their carers, but as these are not first-person accounts they may not accurately or fully convey the views of the person represented. Only one participant was from a minority ethnic community; however, we have also explored the COVID-19-related experiences of a group of people with dementia and carers from minority ethnic communities participating in a dedicated IDEAL programme workstream and will report these separately. We were not able to re-interview all participants, and therefore took the decision to prioritise follow-up interviews with those who were experiencing most difficulty in coping at the time of the initial interview; while this provided useful additional insights into their experiences, any changes for those who were coping well at the time of the initial interview would have been missed. The key strengths of our study are that the work is situated within the conceptual framework of the IDEAL programme and that participants were drawn from this existing well-characterised cohort, we had effective public and private involvement from the well-established ALWAYs group, and that we were able to follow up a subset of participants to identify changes linked to the lifting of restrictions.

Conclusions

COVID-19 social restrictions, challenging for all, posed significant additional challenges for people with mild-to-moderate dementia living in the community and their family carers. While some were resilient and coped well, others experienced a range of negative impacts, with varying degrees of improvement as restrictions were eased. This exceptional situation provides a natural demonstration of the way in which social and psychological resources shape the potential to ‘live well’ with dementia, and how an unhelpful social context can exert a negative impact on the everyday functional ability for people with dementia, both of which were evident in the accounts of those interviewed for this study. While a basic level of support, such as a regular ‘just checking’ phone call, is recommended for all, the observation of different levels of coping in our sample points to the value of a more personalised approach whereby the level of further practical and emotional support is aligned with the needs and coping ability of the person with dementia, carer or dyad.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X21001719

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the people with lived experience of dementia who shared their personal experiences during a challenging time. We gratefully acknowledge the support and input of the ALWAYS (Action on Living Well: Asking You) group whose members have commented on early findings and provided valuable advice based on their personal experience, skills and expertise. We would like to acknowledge the funders of IDEAL and IDEAL-2. ‘Improving the experience of Dementia and Enhancing Active Life: living well with dementia. The IDEAL study’ was funded jointly by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) (grant number ES/L001853/2; Investigators: L. Clare, I. R. Jones, C. Victor, J. V. Hindle, R. W. Jones, M. Knapp, M. Kopelman, R. Litherland, A. Martyr, F. E. Matthews, R. G. Morris, S. M. Nelis, J. A. Pickett, C. Quinn, J. Rusted and J. Thom). ESRC is part of UK Research and Innovation (UKRI). The IDEAL-2 study is funded by the Alzheimer's Society (grant number 348, AS-PR2-16-001; Investigators: L. Clare, I. R. Jones, C. Victor, C. Ballard, A. Hillman, J. V. Hindle, J. Hughes, R. W. Jones, M. Knapp, R. Litherland, A. Martyr, F. E. Matthews, R. G. Morris, S. M. Nelis, C. Quinn and J. Rusted). LC also acknowledges support from the NIHR Applied Research Collaboration South-West Peninsula. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the ESRC, UKRI, NIHR, the Department of Health and Social Care, the National Health Service or the Alzheimer's Society. The support of ESRC, NIHR and the Alzheimer's Society is gratefully acknowledged.

Author contributions

GO'R designed the analysis, conducted the interviews, performed the analysis and wrote the draft paper. CP contributed to the design, contributed to analysis, took part in discussions about the data analysis and interpretation of the data, made edits and suggestions to drafts, and gave final approval of the version to be published. CQ contributed to the design, took part in discussions about the data analysis and interpretation of the data, made suggestions and edits to drafts, and gave final approval of the version to be published. EvdH contributed to analysis and interpretation of the data, made edits and suggestions to drafts, and gave final approval of the version to be published. AH contributed to the design, took part in discussions about the data analysis and interpretation of the data, made edits and suggestions to drafts, and gave final approval of the version to be published. RL contributed to the design, organised and facilitated the ALWAYs group contributions, took part in discussions about the data analysis and interpretation of the data, made edits and suggestions to drafts, and gave final approval of the version to be published. CV contributed to the design, took part in discussions about the data analysis and interpretation of the data, made edits and suggestions to drafts, and gave final approval of the version to be published. LC conceptualised the study, contributed to the design, took part in discussions about the data analysis and the interpretation of data, drafted sections of the paper, made edits to other drafts, and gave final approval of the version to be published.

Financial support

IDEAL COVID-19 Dementia Initiative (IDEAL-CDI) was funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The project team were: L. Clare, C. Victor, C. Quinn, A. Burns, T. Williamson, C. Todd, A. Hillman, R. Litherland, K. Oliver and C. Pentecost. This report presents independent research funded by the NIHR Policy Research Unit in Older People and Frailty (Policy Research Unit Programme reference number PR-PRU-1217-21502). The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

Ethical approval was obtained as an amendment to the IDEAL programme from the Wales Research Ethics Committee 5 on 7 May 2020 (reference number 18/WA/0111). Health Research Authority and Health & Care Research Wales approval was issued on 10 May 2020.