Introduction

Recent years have witnessed an emerging policy consensus around the benefits of empowering people living with dementia to remain active participants in their local communities as part of a shift away from institutionalisation (World Health Organization, 2017; Alzheimer's Disease International, 2018). In England and Wales, Scotland and Sweden the respective governments have formulated national plans and strategies for dementia with an emphasis upon social inclusion and quality of life, and, to varying degrees, supported by a commitment to fostering dementia-friendly communities (Department of Health, 2012; Department of Health and Social Care, 2015; The Scottish Government, 2017; Socialdepartementet, 2018). A dementia-friendly community has been defined as ‘a place or culture in which people with dementia and their carers are empowered, supported and included in society, understand their rights and recognize their full potential’ (Alzheimer's Disease International, 2016: 10).

A key factor in sustaining quality of life and wellbeing in later life is through access to the social environment surrounding the home, defined in many Western cultures as ‘the neighbourhood’ (Wiles, Reference Wiles2005; Bowling, Reference Bowling2008; Day, Reference Day2008). There are many definitions of what a neighbourhood is, but in this study, we are focusing particularly upon the social environment and the ways in which locally situated relationships and contact are developed, maintained and alter for people living alone with dementia. In this context, neighbourhood conditions have been argued to play a significant role in mediating connectivity and social inclusion/exclusion (Milligan et al., Reference Milligan, Gatrell and Bingley2004; Age UK, 2018). As social networks constrict, this can lead to loneliness with attendant implications for both mental and physical health (Larson, Reference Larson1990; Burger, Reference Burger1995; Victor et al., Reference Victor, Scambler, Bond, Victor, Scambler and Bond2009). There is mounting evidence that the risk of social isolation is compounded by the onset of illness or disability (Tomaka et al., Reference Tomaka, Thompson and Palacios2006; Hilberink et al., Reference Hilberink, van der Slot and Klem2017) and following the onset of dementia (Fratiglioni et al., Reference Fratiglioni, Wang, Ericsson, Maytan and Winblad2000). It is helpful to distinguish between isolation, which is the objectively defined situation of being alone with an absence of social interactions and often linked to being confined at home (Larson, Reference Larson1990; Burger, Reference Burger1995) and loneliness, which is subjectively defined and based upon a perceived lack of social relations (Perlman and Peplau, Reference Perlman, Peplau, Gilmour and Duck1981). Existing research has demonstrated the extent of social isolation experienced by people living with dementia who reside in the community (Innes et al., Reference Innes, Archibald and Murphy2004; Batsch and Mittelman, Reference Batsch and Mittelman2012; Alzheimer's Society, 2013). This indicates that we need more in-depth knowledge of how this comes about and how it might be remedied, and hence the intention of this study is to explore the experience of neighbourhood for people living alone with dementia.

It is estimated currently that over 50 million people are living with a dementia diagnosis worldwide. This number is anticipated to increase to 152 million by 2050 (Alzheimer's Disease International, 2018). Demographic projections show that people living in single households will continue growing steadily across many Western and North European countries, and that older women are the fastest rising section of the single householder population (Sundström et al., Reference Sundström, Westerlund and Kotyrlo2016; United Nations, 2017). Given the correlation between dementia and ageing, the ageing population living alone in Europe includes an increasing proportion of those with dementia (Prescop et al., Reference Prescop, Dodge, Morycz, Schulz and Ganguli1999; Gaymu and Springer, Reference Gaymu and Springer2010; Prince et al., Reference Prince, Wimo, Guerchet, Ali, Wu and Prina2015). In Canada, France, Germany, the United Kingdom (UK) and Sweden, more than one-third to a half of the population of people with dementia residing in the community are living in single households (Ebly et al., Reference Ebly, Hogan and Rockwood1999; Nourhashemi et al., Reference Nourhashemi, Amouyal-Barkate, Gillette-Guyonnet, Cantet and Vellas2005; Alzheimer's Society, 2013; Eichler et al., Reference Eichler, Hoffmann, Hertel, Richter, Wucherer, Michalowsky, Dreier and Thyrian2016; Odzakovic et al., Reference Odzakovic, Hydén, Festin and Kullberg2019). Yet, despite this increase in single householders with dementia, there is currently limited awareness of the particular challenges associated with living alone with dementia, and this applies to emerging dialogues concerning dementia-friendly communities (Alzheimer's Society, 2013; Age UK, 2018; Odzakovic et al., Reference Odzakovic, Hellström, Ward and Kullberg2018). Existing evidence has shown that people with dementia who live alone are more prone to (unplanned) hospitalisation (Ennis et al., Reference Ennis, Larson, Grothaus, Helfrich, Balch and Phelan2014); are at greater risk of malnutrition (Nourhashemi et al., Reference Nourhashemi, Amouyal-Barkate, Gillette-Guyonnet, Cantet and Vellas2005); are likely to be admitted to long-term care at an earlier point in their journey with dementia (Yaffe et al., Reference Yaffe, Fox, Newcomer, Sands, Lindquist, Dane and Covinsky2002); are less well connected to formal services (Webber et al., Reference Webber, Fox and Burnett1994); and lacking the advocacy of a co-resident carer (Eichler et al., Reference Eichler, Hoffmann, Hertel, Richter, Wucherer, Michalowsky, Dreier and Thyrian2016). However, to date, little is known of the lived experience of neighbourhood for people with a dementia who live alone and, in particular, how they manage the potential for loneliness and maintain connections to a wider network within the local community.

Background: neighbourhood and dementia

The neighbourhood represents a particularly significant context within which social connections are forged over the lifecourse (Kallus and Law-Yone, Reference Kallus and Law-Yone2000; Bowling, Reference Bowling2005; Blackman, Reference Blackman2006). In fields such a gerontology and public health, the neighbourhood is a prominent unit of analysis, not only due to its proximity to the home and the frequency of social encounters that take place within it, but also because it is closely linked to questions of identity and our sense of self. Thus, Blackman (Reference Blackman2006: 29) argues that ‘neighbourhoods are where we feel more or less in control of the surroundings in which we live, and more or less buoyed by the status of where we live’; while Bowling (Reference Bowling2005) argues that neighbourhoods sustain an often under-appreciated extent of social capital where personal attachment and social networks form over time. It is the cumulative nature of our connection to the neighbourhood over time that gives it a unique quality, as captured by Rowles’ (Reference Rowles1981) notion of ‘insideness’ which underscores the exchange between person and place that develops over the lifecourse.

Earlier research about people living alone with dementia at home has tended to focus rather narrowly on support in the home, where ‘community-dwelling’ is often equated with support aimed at enabling individuals to ‘manage at home’ (Lehman et al., Reference Lehman, Black, Shore, Kasper and Rabins2010; Miranda-Castillo et al., Reference Miranda-Castillo, Woods and Orrell2010; Alzheimer's Society, 2013). There is also evidence that those who live alone have more restricted opportunities for sociability (Duane et al., Reference Duane, Brasher and Koch2011). However, a growing body of research has begun to explore how people with dementia interact with their neighbourhood in everyday life (Blackman et al., Reference Blackman, Van Schaik and Martyr2007; Duggan et al., Reference Duggan, Blackman, Martyr and Van Schaik2008; Keady et al., Reference Keady, Campbell, Barnes, Ward, Li, Swarbrick, Burrow and Elvish2012; Phinney et al., Reference Phinney, Kelson, Baumbusch, O'Connor and Purves2016; Kelson et al., Reference Kelson, Phinney and Lowry2017; Brorsson et al., Reference Brorsson, Ohman, Lundberg, Cutchin and Nygard2018; Ward et al., Reference Ward, Clark, Campbell, Graham, Kullberg, Manji, Rummery and Keady2018), and this has included attention to those living alone with the condition (Odzakovic et al., Reference Odzakovic, Hellström, Ward and Kullberg2018). For instance, evidence suggests that regular walks in/through the neighbourhood support a variety of different types of interaction and social encounter for people living with dementia (Odzakovic et al., Reference Odzakovic, Hellström, Ward and Kullberg2018; Ward et al., Reference Ward, Clark, Campbell, Graham, Kullberg, Manji, Rummery and Keady2018).

To date, less emphasis has been given to understanding the broader social circumstances of people living alone with dementia or in revealing how people with dementia themselves tackle the challenges of living alone with a progressive condition. The purpose of this study is therefore to examine a sub-set of data from the Neighbourhood: Our People, Our Places (N:OPOP) project (detailed below) in order to focus upon how people living alone with dementia establish social networks and relationships in a neighbourhood context, and how they are supported to maintain this social context within everyday life. We argue that this perspective on the challenges of neighbourhood living for single householders is essential to inform care at home and the development of ‘dementia-friendly communities’ (Alzheimer's Society, 2013), not least in better understanding how to reduce the risk of isolation and loneliness for what we know to be a rapidly growing proportion of the community-dwelling population of people with dementia (United Nations, 2017). This study, therefore, aims to explore the experiences of people living alone with dementia in a neighbourhood context and will address one main question: ‘How do people living alone with dementia maintain their social networks and connections?’

Methods

The context of the study

This study reports findings from the N:OPOP project, a five-year international study (2014–2019) that forms an integral part of a wider research programme ‘Neighbourhoods and Dementia: A Mixed Methods Study’ (Keady, Reference Keady2014) funded in the UK under (action point 12 of) the first Prime Minister's Challenge on Dementia (Department of Health, 2012). The aim of N:OPOP is to investigate how neighbourhoods and local communities can support people with dementia to remain socially and physically active. N:OPOP extends over three field sites: Greater Manchester in Northern England, ‘the Central Belt of Scotland’ and the county of Östergötland in Sweden. In this study, we chose to explore a sub-set of the data from the three field sites, as our analysis revealed that individuals living alone with dementia face distinctive challenges and conditions in their efforts to remain connected to their communities, despite often being invisible as a group within policy, practice and research.

Research design

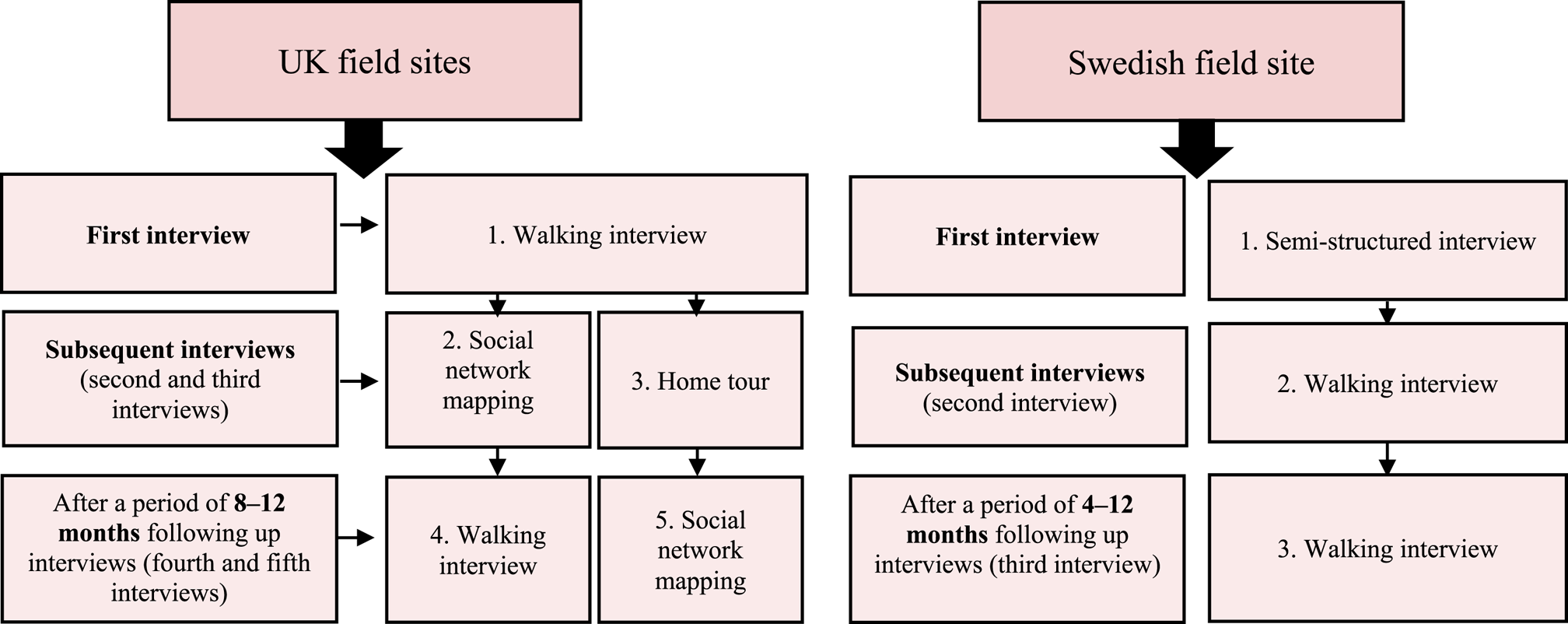

The study employed a mix of qualitative data collection methods (Morse and Niehaus, Reference Morse and Niehaus2009) aimed at supporting the participation of people with dementia, and was framed by a social constructionist paradigm (Berger and Luckmann, Reference Berger and Luckmann1966). We used walking interviews (Carpiano, Reference Carpiano2009; Clark and Emmel, Reference Clark and Emmel2010; Clark, Reference Clark2017; Kullberg and Odzakovic, Reference Kullberg, Odzakovic, Keady, Hyden, Johnson and Swarbrick2017), social network mapping (Emmel and Clark, Reference Emmel and Clark2009; Clark, Reference Clark2017; Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Clark, Keady, Kullberg, Manji, Rummery and Ward2019) and home tours, which drew upon Pink's (Reference Pink2009) ‘walking with video method’, and where possible the network maps and walking interviews were repeated after a period of 8–12 months. In the English and Scottish field sites, we started with interviews outside the home, using walking interviews (Carpiano, Reference Carpiano2009; Clark and Emmel, Reference Clark and Emmel2010; Clark, Reference Clark2017; Kullberg and Odzakovic, Reference Kullberg, Odzakovic, Keady, Hyden, Johnson and Swarbrick2017) before moving on to home-based interviews using social network mapping and/or home tours (Emmel and Clark, Reference Emmel and Clark2009; Pink, Reference Pink2009; Clark, Reference Clark2017; Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Clark, Keady, Kullberg, Manji, Rummery and Ward2019). In the Swedish field site, walking interviews were preceded by semi-structured interviews (Polit and Beck, Reference Polit and Beck2016), the latter being used to explore sources of support for the participants and to obtain an understanding of the participants’ everyday life through questions related to the home and neighbourhood. In Sweden, we began the research relationship with semi-structured interviews in the home, as a rapport-building measure, before progressing to walking interviews. The differing order and approach in part reflected perceived cultural differences, in what would be most comfortable for the participants. The approach of using multiple data collection methods supported a participatory ethos by involving people with dementia as a part of the research process (Swarbrick et al., Reference Swarbrick, Davis and Keady2016) to create new knowledge in partnership.

By combining a mix of qualitative methods, we were able to triangulate data (Denzin, Reference Denzin1978; Polit and Beck, Reference Polit and Beck2016) exploring the phenomena of neighbourhood connections for people living alone with dementia while comparing/contrasting neighbourhood experiences across different welfare systems and political contexts. We used open questions during data collection to encourage the participants to share the experience of living alone with dementia such as ‘Could you describe your social networks?’, ‘Tell me who you know’?, ‘Who would be the first person that you will contact if you need some help? and ‘What do you like about where you live?’, and clarifying questions (Lincoln and Guba, Reference Lincoln and Guba1985) such as ‘Tell me, how has that affected you?’ The length of the interviews varied between 25 and 134 minutes. All interviews were audio-recorded. The interviews were transcribed by certified transcriptionists with some interviews in the Swedish field site transcribed by the authors (EO, AK). The interviews from the Swedish field site were translated into English by a translator with a Scandinavian background. Hence all interviews were made available and could be exchanged between the authors.

Multiple data collection methods

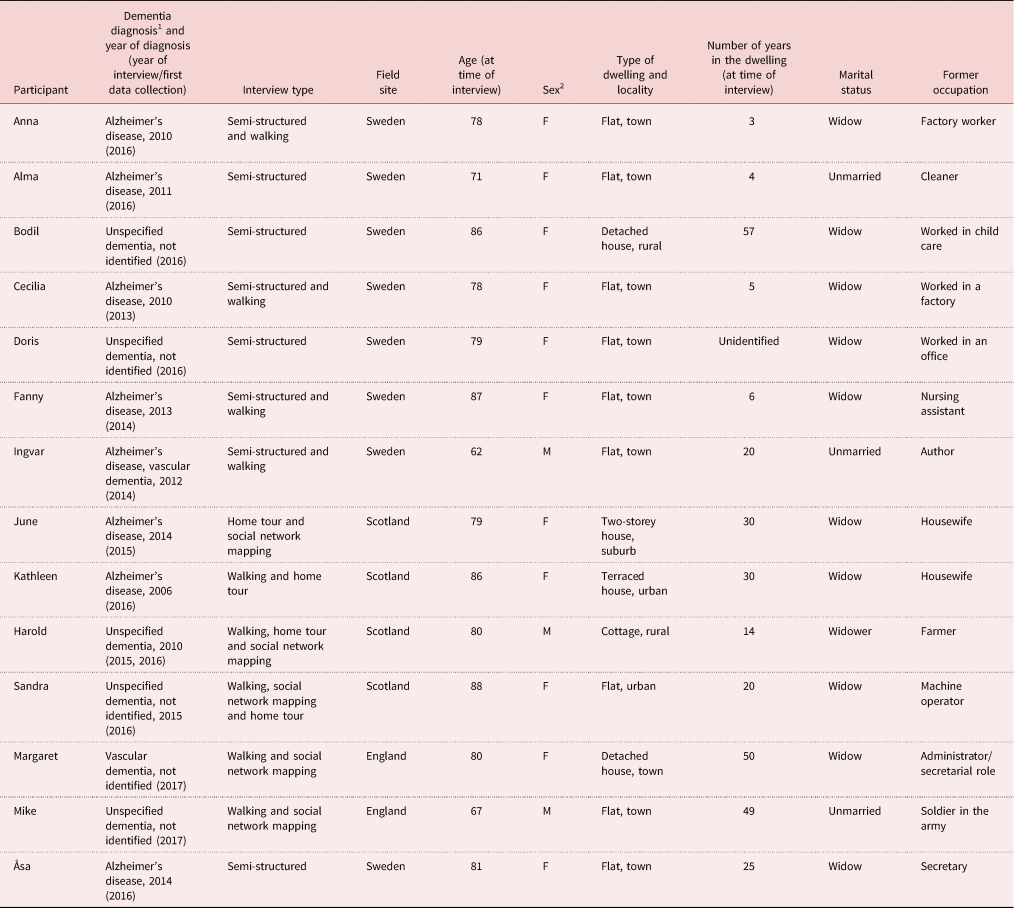

Across all three field sites, walking interviews were used to engage in in situ discussions where participants were asked to take the researcher on a preferred or commonly used route through their neighbourhood. As discussed by Carpiano (Reference Carpiano2009), Clark and Emmel (Reference Clark and Emmel2010), Kullberg and Odzakovic (Reference Kullberg, Odzakovic, Keady, Hyden, Johnson and Swarbrick2017) and Odzakovic et al. (Reference Odzakovic, Hellström, Ward and Kullberg2018), walking involves bodily movement and synchrony, creating a connection and spontaneous conversation about the local environment and social life of the neighbourhood. Such an approach is well-suited to research involving people with dementia as much of the topic of our discussions was readily to hand, providing immediate and material prompts to support the narratives of neighbourhood life shared by the participants. Moving into the homespace, the UK field sites employed home tours, which were filmed if permission was given by the participant. Here, the participants took us on a tour to describe what was important for them, such as objects and different rooms and spaces within the home (Pink, Reference Pink2009). We also used social network mapping (Emmel and Clark, Reference Emmel and Clark2009; Clark, Reference Clark2017; Campbell et al., Reference Campbell, Clark, Keady, Kullberg, Manji, Rummery and Ward2019) while visiting the participants at home. These were open-ended interviews where we asked the participants to ‘map out’ their social networks with a focus on the different individuals and groups to whom they were connected. This approach evoked questions not only about the actual social networks and relationships, but also the relationships they missed or wanted in their life. In the study, interview transcripts from the multiple data collection methods have been the source for analysis (see Table 1). All names in the study are pseudonyms.

Table 1. Participants’ characteristics

Notes: 1. No information about the stages of dementia is collected as the lived experiences of dementia is central. 2. F: female; M: male.

Recruitment and data collection

The recruitment of participants aimed to include people living with dementia (those with a diagnosis and those providing care and support) and started after ethical approval was secured in each field site. Ethical approval was obtained from the NHS Health and Social Care Research Ethics Committee in the UK and the Regional Ethical Review Board in Linköping (the county of Östergötland, Sweden). In England and Scotland, local and national voluntary and community organisations were helpful during the recruitment process while, in the Swedish field site, the research team contacted and visited health-care staff working at memory clinics, primary health care and day care centres in the county of Östergötland, as a route to recruitment. In total, 129 participants were selected to participate across the three field sites and of those 67 were participants with a diagnosis of dementia and 62 were primary carers. We selected participants from the total of 129 participants based on the following inclusion criteria: living alone (without a co-habiting partner/children/next of kin), not sharing their living accommodation with others (i.e. one-person household). All the participants were community-dwelling, and able to give oral and/or written informed consent.

Figure 1 shows an overview of data collection in the three field sites. The first contact with potential participants was either by letter and/or telephone call. After the first interview, the researchers asked to return to conduct subsequent interviews after some months (Figure 1) as an opportunity to explore any changes over time to the participant's situation. During the interviews, a process consent approach (Dewing, Reference Dewing2008) was followed with regular reminders about the research. The participants and/or care-givers decided the time and place for the interviews and none of the participants withdrew during the interviews. Some of the participants only took part in one round of interviews (at times this was due to a decline in health or having moved on from their original address) while others agreed to participate in a follow-up interview (see Table 1). In total, 14 community-dwelling people living alone with dementia participated in at least one of the multiple data collection methods in the study. The participants ranged in age from 62 to 88 years; 11 were women and three were men (Table 1). Each had a diagnosis of dementia although some chose not to or were unable to reveal the specific type of dementia. Some participants were managing at home without formal support while others had regular visits from different dementia practitioners, including home care services.

Figure 1. Overview of how data collection was undertaken in the three field sites.

Data analysis

An inductive approach framed thematic analysis of interview transcripts from the multiple data collection methods (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). Analysis was driven by our intention to provide a rich overall description, where the experiences of participants was central. For this study, the first author followed six phases for data analysis, which included re-reading the data several times and note-taking. If any questions arose, the first author discussed these with the wider team. The data were inductively coded from the ‘bottom up’ directly from the interviews. Here, the aim was to be as close to the meanings within the data from the participants’ perspectives as possible. The initial codes were then clustered together to identify potential sub-themes, followed by reviewing and developing sub-themes from the previous phase. The themes were then checked in relation to the coded extracts and data-set. The authors (EO, AK, IH, RW) discussed the sub-themes together to ensure consensus and agreement of themes to achieve validity (Nowell et al., Reference Nowell, Norris, White and Moules2017). In the fifth phase, the sub-themes were defined and named alone and together with descriptions to identify the overall story of the data. The main themes were constructed here and discussed by the authors (EO, AK, IH, RW). Finally, the written-up findings were circulated to the entire research team for sense-checking and to ensure consensus in our interpretations.

Findings

Our findings reveal how people living alone with dementia actively manage and maintain their social networks and relationships, often in the face of considerable challenges to efforts to stay connected. Participants’ actions were crucial to sustaining a social life in a neighbourhood context and staving off the threat of isolation. Our analysis revealed four main themes: making the effort to stay connected, befriending by organisations and facilitated friendships, the quiet neighbourhood atmosphere and changing social connections.

Making the effort to stay connected

Across all three field sites, participants spoke of their efforts to stay connected, often in the face of social losses as contact with friends and sometimes even family decreased following a diagnosis of dementia. Certain core relationships with family, friends and neighbours had evolved over many years and withstood the impact of the diagnosis. For instance, ties with some close family members were reported to have been sustained, much as before the onset of dementia, and the resilience of these connections underlined their value to those involved. Maintaining a relationship with family, often especially with children, also helped to facilitate broader connections to friends and neighbours. Children gave ongoing prompts and reminders, made bookings for events and carried out research into local social opportunities that were passed to their parents. In this way social networks were collectively managed even when this support was offered from a distance:

The family were here in this room and it was a lovely sunny afternoon. And loads of people came. They stayed the night. We had a real party. They ended up having a glass of wine and I made them beds up. (Kathleen, Scotland)

It is really because my children go to the church then Father Peter visits me at home as often he can. (Margaret, England)

Participants without children reported focusing their efforts on a circle of friends or at times just one or two key social contacts, and these relationships similarly played a crucial role in maintaining wider neighbourhood connections. The participants outlined their efforts both to maintain existing relationships but also to establish new ones as a response to their depleted social networks. In some of our discussions, we identified a longing to engage in daily social meetings in the neighbourhood as a means to maintaining a degree of continuity in everyday life. For instance, June was one of the participants who worked hard to keep up relationships with her friends:

I can still go out like … Well, my friends come. We go to [local venue] and we sometimes have a pub lunch. (June, Scotland)

Many participants highlighted the significance of having a friend they could chat with and who kept an eye on them, which provided a sense of reassurance. Sometimes, even fairly weak connections were helpful just by knowing that someone was looking out on their behalf. However, participants also faced the challenge of seeking out and establishing new contacts and, in some cases, re-building their networks. Some participants reported wanting to participate in different clubs or meeting places in order not to be alone. Doris shared with us how her experience of living alone could sometimes tip over into a sense of loneliness, a feeling that had become more acute since her receipt of a diagnosis of dementia. Doris was a 79-year-old woman, living in a flat and diagnosed with a dementia (the type and time since diagnosis were not specified during the interview). She received support from the municipality-run home care service and had an alarm installed at the front door, following an incident where she had left her apartment in the middle of night. After the alarm was installed, Doris told us that she had begun to feel like a prisoner in her own home, and had been increasingly neglected by her neighbours. Before the dementia diagnosis, Doris had a group of friends that she socialised with, but post-diagnosis, as she noticed herself forgetting things and sometimes repeating her questions, she found herself increasingly excluded from her social circle:

We were a group of friends that I joined many years ago. On one occasion we met up to have a chat with coffee and cake then they said ‘should we go over there [venue for the next meet-up]’? Well, I said ‘where is the place then?’ ‘Do you not know!’ Those words, they are cutting right through me. I really don't have any friends here. (Doris, Sweden)

It was not only Doris who recounted stigmatising social experiences such as this. Ingvar and Cecilia both had experiences of friendships that had fallen away following their diagnosis. Ingvar reflected:

When you get sick no matter what it is … then friends disappear. Especially, after [being diagnosed with] Alzheimer's.

There was a lack of social awareness regarding what a dementia diagnosis means, but also as these accounts reveal, a lack of acceptance and even compassion, which led to exclusion from social networks over time. Social losses were a feature of most people's post-diagnostic experience, although these were not necessarily interpreted as linked to dementia. For instance, Fanny (Sweden) ascribed her situation to ageing: ‘One does not have that many guests, when one gets to this age.’

Not everyone had thriving local connections, for instance we spoke to some people who hardly knew their neighbours and who felt ambivalent about reaching out to these physically proximate connections. Some participants noted that contact with neighbours was limited to sharing the newspaper or to a brief chat in the staircase of their dwelling but the regularity of such brief encounters over time helped to maintain their sense of connection:

This [neighbour] right over, I do not have much contact with. But the other neighbour usually comes in and wants to know how I'm feeling today. They are all old neighbours from a way back. (Åsa, Sweden)

For others, neighbours provided a low but consistent level of daily support and this expectation or practice of supportive neighbouring seemed more pronounced in the UK field sites than for some of the Swedish participants. Some reported that their neighbours visited daily just to chat, often without any invitation, or called them on the telephone to hear their voices. For others, their neighbours represented a degree of latent support that they knew could be relied upon when most needed, for instance Margaret (England) reported that her neighbours visited her almost daily, but also had her daughter's number in case of emergency: ‘They've got Tina's phone number and she's got theirs but we've never used it yet.’

Some participants made regular forays outdoors where there were good chances of more spontaneous encounters. Interviewees described how they would seek out these popular spaces within their neighbourhood in the hope of a chance encounter but very much only during daylight hours. Such places included parks, pubs or cafés and often led to opportunistic encounters with ‘regulars’ or staff, as Mike (England) noted of an owner of the café that he visits daily to drink his morning coffee and to meet old friends: ‘He always has a chat, but he's quite funny at times.’ In Sweden, there were fewer such neighbourhood-based meeting places so opportunities for spontaneous encounters were more limited due to the cultural tradition of meeting people outdoors. However, the participants revealed various plans and strategies to heighten the chances of social interaction in their neighbourhood. This could simply involve taking a walk or carefully selecting where they sat (e.g. on a bench in a busy area). These strategies supported a sense of inclusion and neighbourhood participation, as outlined by Anna and Fanny:

This summer was too long, then it [seating area in neighbourhood] almost becomes a small meeting point for pensioners. It's our pleasure, we count cars here. I can sit here for a while and sometimes there's nobody to talk to, sometimes there is someone that I can talk with. (Anna, Sweden)

Then one always meets someone one can talk to … but I am out sometimes, and there are [usually] a few people around. (Fanny, Sweden)

As Fanny and Anna indicate, the planning for spontaneous encounters in the neighbourhood results in new ways to connect to other people and create social networks that they could sustain. Despite the differences between the field sites, people clearly took pleasure from and invested real effort in maintaining these networks and relationships.

Befriending by organisations and facilitated friendships

A number of organisations and formal service providers offered activities every week that the participants were looking forward to. In the UK, these were primarily led and organised by third-sector and charitable groups whereas in Sweden the likelihood was that support came from the public sector, mainly the local municipality (county council). For many people living alone this support represented a fundamental aspect of their social contact. Home care visits provided an opening for sociability and opportunities for exchange of news and events. For some participants, a visit to the voluntary organisations and formal services opened up a social world where they could meet others with the same condition. In this way, service providers played the role of ‘friendship facilitators’ (Ward et al., Reference Ward, Howorth, Wilkinson, Campbell and Keady2012), creating connections between people living with dementia that could evolve into supportive and close affiliations. The activities on offer were also perceived as good for their health and wellbeing:

I go to a group that Philip [son] … he knew the fella that ran it … I was only there last week. They had a dancing session last week when I went. It is good for your brain, and they're all very friendly. (Margaret, England)

The volunteers and professionals working within these organisations and local hubs were sometimes described by participants as friends rather than being seen as workers, while the overall atmosphere was described as familiar and free of stigma. As such, these local venues represented a safe space to venture out to within the neighbourhood. Crucially, these were spaces that provided opportunities for peer support and more informal camaraderie. Some participants indicated that these organisations were the first point of contact for support if anything were to happen to them. Mike had been diagnosed with dementia (but chose not to specify what type of dementia at the time of the interview). He had been a soldier in the army but spent much of his adult life unemployed due to ill-health. After being diagnosed with dementia, Mike revealed how a support worker from a charitable organisation had encouraged him to attend a book club and, in this way, had created social opportunities for him, at a time when he had felt cut off and subsequently depressed:

I found out about it when I got my diagnosis. They gave me a leaflet and gave me a number to ring. Linda from [charity] came and took me to the book club that is run by [the organisation]. They are a really important part of my life now. (Mike, England)

Interviews conducted in the Swedish field site found no voluntary/third-sector organisations (or designated link workers) involved in the support of people with dementia living alone in the community, as the infrastructure for community-based dementia care differs from the UK in this respect. Instead, it tended to be more formal day care centres that served as places where the participants could meet others and participate in different activities during the week. Social activities included sports and exercise classes, and opportunities for eating lunch together. For Doris, the day care centre offered a degree of respite from the isolation of life at home:

I'm happy about [day care centre] because it has saved me. I was terribly alone a lot and I can honestly say the day care centre was what saved me. (Doris, Sweden)

The befriending role of organisations and formal services offered participants a focus for social activities and membership of a network that were free of the stigma they perceived and experienced in other public venues and at social events. However, there were some notable differences here between the UK and Swedish field sites in terms of which sector and type of organisation took responsibility for co-ordination and day-to-day running of these neighbourhood hubs. In Sweden, there were few indications of a more voluntary engagement of care in the area where we undertook the research, or any real signs of wider involvement of local businesses, retailers or venues such as cafes. Indeed, the move to a more diversified spread of community-based support is yet to establish itself in Sweden, when compared to efforts in the UK to promote dementia-friendly communities. Instead, the municipalities (local county councils) in Sweden took responsibility for day care provision and any other meeting places that people living alone with dementia might frequent. In Sweden, the universal approach of welfare system is developed where home care is available to all citizens irrespective of income, and is instead based on individual's needs (Rostgaard and Szebehely, Reference Rostgaard and Szebehely2012). By contrast, in England and Scotland, there was clear evidence of public-sector services having receded, with voluntary/third-sector groups serving as the primary source of support and connection within the community. However, irrespective of the nature of the organisations involved, participants were clear that the support they received served as an important buffer to isolation and the potential for depression.

The quiet neighbourhood atmosphere

The third theme that many of our interviewees discussed with us concerns the neighbourhood atmosphere and, in particular, their feelings about periods when the area where they lived fell quiet. During these times, such as when fellow neighbours were at work or school/college, the neighbourhood could feel quite deserted. The tone and atmosphere of a particular neighbourhood also evolved more slowly over time as people moved on and families grew up and moved out. Cecilia shared her experience of a gradually quietening atmosphere after a number of local children, whom she had enjoyed watching and listening to play in the street, moved away from her neighbourhood. Every day Cecilia had sat on her sofa in the kitchen, looking out through the window at the children playing outside, and this had proved a restorative experience after a heart attack:

There were many immigrant children on the street playing in the summer. They were so lovely to look at, how they were playing. Then one day I just said: where did all the kids go? I miss the kids! Now it's so quiet that you just wish for the sound of other people. (Cecilia, Sweden)

For many people a quiet neighbourhood atmosphere was experienced as anything other than relaxing or peaceful, participants discussed feelings of insecurity during times when there were no people in sight. This underlined how just seeing people outside provided a degree of neighbourhood connection but also perhaps how it more deeply reinforced a sense of neighbourhood identity. As such, many of the participants who lived alone described taking steps to seek out those places where they knew that they would see people walking or moving around, even if these were complete strangers. This underlines the importance of public spaces as a way of mitigating the quietness of residential areas. The windows and/or balcony in the home were also essential to being able to keep a visual link to a wider world beyond the home. For Kathleen, the window offered a view over her enclosed garden. She could see the cat sitting under the tree or when the postman and her carers came to visit her. The window maintained her sense of connectedness to the world outside and offered opportunities to witness the spatio-temporal changes near home (Coleman and Kearns, Reference Coleman and Kearns2015). Both Kathleen and Alma shared how their windows enabled them to feel connected to life outside, offering a degree of release from domestic confinement, and decreasing their sense of solitude:

I love the windows; it gives me a feeling of freedom. I'm not closed in. (Kathleen, Scotland)

Look what a nice view I have. And I can see everyone who goes to the day care centre. But I can also see those who are walking and shopping it may seem a bit curious. (Alma, Sweden)

For Sandra, her television provided a means to break the silence during periods of quiet and inactivity in the neighbourhood, especially during holidays, which posed a particular challenge for those left behind:

Oh, it's deathly quiet. It's too quiet, sometimes, because I forget to turn the telly down a bit, and … of course, because folk go on holiday and you miss them. (Sandra, Scotland)

Even if Sandra, and others in her position, did not actually watch the television, the sound provided background noise that prevented the silence becoming oppressive. While different people coped with living on their own in different ways, many noted how their sense of solitude and isolation was compounded when a quiet atmosphere descended on the local area. During such times, participants reported actively seeking out activity and movement, and gravitating towards areas they knew would offer opportunities for sociability.

Changing social connections

Much has previously been written about the loss of social connections and gradually shrinking networks as people age, and there is some indication that this experience intensifies in the fall-out from illness or disability in later life (e.g. Duggan et al., Reference Duggan, Blackman, Martyr and Van Schaik2008). Evidence from the N:OPOP study (Ward et al., Reference Ward, Clark, Campbell, Graham, Kullberg, Manji, Rummery and Keady2018) supports this reported pattern of social losses and it was clear from our discussions with participants that stigma was often perceived to play a decisive role. However, a particular message from our research is that people with dementia are by no means passive in the face of these losses, taking action to redress the situation, which we would argue needs to be both recognised and better supported by those who provide services in the community. Importantly, solitude (as distinct from loneliness or isolation) was by no means reported to be an entirely negative experience, and interestingly for the men we spoke to who lived alone, it was valued as a source of freedom and privacy that upheld a sense of self-reliance and independence. Thus, both Ingvar (who is a writer) and Harold shared similar perspectives on solitude as a freedom they wished to maintain:

In a way I'm quite asocial as well and here's deathly quiet. But it's good for me … In my writing, you live with … with the people in the novel so to speak … I do. (Ingvar, Sweden)

Yeah, I'm kind of my own buddy. I'm really quite home-based. (Harold, Scotland)

However, many participants shared with us experiences of involuntary solitude or loneliness. They wanted to establish new relationships and/or to sustain old friendships but the stigma surrounding dementia made this difficult. Also for other individuals who lived alone, the impact of stigma seemed particularly damaging, compounding existing feelings of loneliness that may have arisen from the death of a partner or close friend:

I'd love to have someone in my life but how do I go about making that happen? It would be so nice to have someone who came home to me. But I'm just lonely, and I feel as if I can't do anything about it. (Bodil, Sweden)

Many participants felt compelled to take action to tackle an encroaching sense of isolation or loneliness but were often not adequately supported to do so, or were even perceived to be lonely. Anna and Harold shared their approach to just meeting other people in their neighbourhood:

I go on Fridays, well not every Friday but quite often so we play bingo, that was provided by the local pensioners’ organisation. (Anna, Sweden)

I knew everybody. Now I hardly know anybody. I wave at cars and … but I don't … I mean, at one time, well, the postman knew where the key of our house was and he'd open the door and make a cup of tea or had a sandwich or a cake. (Harold, Scotland)

Our interviews underlined that greater knowledge and awareness of the particular challenges faced by people living alone with dementia is required, both at a broader community level but arguably especially so in social policy, and for health and social care professionals working in primary health care and home care services. As we shall come on to argue below, the advent of dementia-friendly community initiatives has particular significance for the growing number of people with dementia who live alone in the neighbourhood.

Discussion

By exploring the neighbourhood-based relationships of people living alone with dementia, our research has demonstrated not only the desire to stay connected in the face of considerable challenges but the many strategies people employ to achieve this. Emmel and Clark (Reference Emmel and Clark2009) revealed that neighbourhoods are comprised of social networks, often built up over a lifetime, and embedded within spatial and temporal contexts. The multiple data collection methods employed in this study were selected with the aim of documenting these emplaced relationships by supporting people living with dementia to show and tell us about them. The idea behind the mix of qualitative methods used in this study was to support and enhance the meaningful contribution to the research by people with dementia. The participatory design challenged the traditional divide between the researcher and ‘the researched’ by seeking to hand greater control of the research process over to the participants.

In many cases the immediate social relationship and first line of contact was with family and children, across all three field sites, and these were vital to maintaining broader neighbourhood connections. Family connections were important in the sense of supporting people's existing social relationships or creating new networks by making plans and organising opportunities to keep neighbourhood connections alive. We found differences between the UK and Swedish field sites regarding relations with neighbours and friends. In England, especially, and in Scotland, daily contact with neighbours was an established facet of people's day-to-day lives, and often these ‘proximate alliances’ facilitated access to the neighbourhood, whether through offers of transport, bringing shopping or simply through imparting local knowledge. These findings in our study are in line with previous research based on the importance of having a trusting relationship with neighbours that supports existing social networks and connection within the neighbourhood for older people (Gardner, Reference Gardner2011) and especially for older women living alone (Walker and Hiller, Reference Walker and Hiller2007). Frazer et al. (Reference Frazer, Oyebode and Cleary2011; see also deWitt et al., Reference deWitt, Ploeg and Black2009, Reference deWitt, Ploeg and Black2010) have also shown that older women living with dementia valued their relationships with neighbours as they helped them in practical and emotional ways so that they could rely on their neighbours if they were in need.

Hand et al. (Reference Hand, Laliberte Rudman, Huot, Pack and Gilliland2018) have also highlighted the power of social interaction and of being involved in community action to improve the agency of older people. Crucially, this study has shown that people living alone with dementia are active agents in the management of their social experience, taking steps both to maintain and re-build the locally embedded networks of which they are a part. So while these relationships had altered over time, not least due to exclusion and stigma, there is a compelling argument for targeting support in helping to maintain connectivity as vital to managing in a community-based context. The exclusion from existing relationships with friends was often something that had arisen after being diagnosed and it is difficult not to attribute these changes to the widespread presence of stigma and discrimination surrounding dementia (Alzheimer's Society, 2008; Batsch and Mittelman, Reference Batsch and Mittelman2012). This insight across all three field sites underscores the ongoing need for broader social education and understanding about dementia and, in particular, what living alone with dementia actually entails and how to reduce the risk of solitude and isolation for a growing proportion of people in our society.

The small number of studies conducted in this area have shown that stigma surrounding dementia could be reduced by maintaining social connections with the local community and promoting a more positive public awareness of dementia through policy (deWitt et al., Reference deWitt, Ploeg and Black2009, Reference deWitt, Ploeg and Black2010; Frazer et al., Reference Frazer, Oyebode and Cleary2011; Alzheimer's Society, 2013). This could promote better social understanding of dementia, meaning that people living alone with the condition would be acknowledged within their neighbourhood, leading to greater inclusion in social networks. Our research confirms the essential role of social connections for people with dementia which is in line with ‘age-friendly cities’ (World Health Organization, 2007) and ‘dementia-friendly communities’ (Alzheimer's Disease International, 2016) policy and initiatives. However, this study goes further to underline the situation of the growing number of people who live alone with dementia, where social support from outside the home helps people to manage at home without becoming isolated or cut off from those around them. A better degree of understanding of the specific challenges to living alone with dementia could improve quality of life and help to address the intersection of social isolation and dementia-related stigma that so many of the people we spoke to had faced in their neighbourhoods.

Formal service providers had a significant role to play for individuals who lived alone. Their function in befriending the participants post-diagnosis, as well as facilitating their connection to a wider network of others living with the condition, unquestionably enabled people to cope better and buffered against the risk of isolation and the attendant threat of depression. The participants we spoke to were very clear about this but also well aware of the rather precarious nature of their situation. The professionals, volunteers and others who attended these hubs were often cast as friends if not as ‘chosen family’. These findings are in line with an earlier study which revealed how facilitated friendships were forged in situations where people with dementia were brought together by a dementia practitioner, enabling them to help each other (Ward et al., Reference Ward, Howorth, Wilkinson, Campbell and Keady2012). This raises awareness and implications about the meaningful role of volunteers and practitioners working in organisations to support people living alone with dementia to find new friends and social networks. Greenwood et al. (Reference Greenwood, Gordon, Pavlou and Bolton2016) and Smith et al. (Reference Smith, Drennan, Mackenzie and Greenwood2018) have shown that volunteers often initially had low knowledge and held stereotyped views about dementia but that this changed as they worked with people living with dementia and carers. Volunteers shared that they supported people living with dementia with social connections and maintaining friendships (Greenwood et al., Reference Greenwood, Gordon, Pavlou and Bolton2016). This reveals the benefits of peer support and contact with befriending organisations that could include a central person that supported the social networks for people living alone with dementia.

The UK has a long tradition of volunteering where this type of social support can be given (National Centre for Volunteering, 2000), in contrast to Sweden where such contributions are yet to be established for supporting people with dementia. In Sweden, the national dementia organisation has yet to establish or provide voluntary support to increase the social life in neighbourhoods. Indeed, the dearth of anything other than public-sector support was a key distinguishing feature between the UK and Sweden. For instance, in Scotland, there is an ambition to provide a year's-worth of post-diagnostic support by a named support worker to people living with dementia (The Scottish Government, 2017). However, in Sweden there were no similar forms of support involving a named contact person. The Swedish National Strategy has stated that early support is important in the municipalities for people living with dementia and carers and highlights the importance of dementia-friendly communities (Socialdepartementet, 2018). However, to date, the voices and perspectives of people living with dementia and their carers have not been clearly represented in the Swedish dementia policy and the potential value of more informal neighbourhood-based social meeting places (apart from day care centres) is largely unacknowledged.

Looking beyond questions of formal care and support, this study underlines the importance of understanding neighbourhoods ‘in time’ as their character and features alter during the 24-hour period. Many of the people we spoke to commented on how it felt when a quiet atmosphere descended upon their local area, sometimes as a result of being left behind when others went off to work or school during the day. Other studies have found that windows were sources for informal interactions and a sense of belonging by getting a smile through the window for older people with limited mobility (May and Muir, Reference May and Muir2015; Musselwhite, Reference Musselwhite2018) and for people living with dementia (Ward et al., Reference Ward, Clark, Campbell, Graham, Kullberg, Manji, Rummery and Keady2018). Just to hear voices or see children playing outside gave hope and a sense of connection, especially for the women to whom we spoke. In previous studies (deWitt et al., Reference deWitt, Ploeg and Black2009, Reference deWitt, Ploeg and Black2010; Frazer et al., Reference Frazer, Oyebode and Cleary2011; Lloyd and Stirling, Reference Lloyd and Stirling2011; Svanström and Johansson Sundler, Reference Svanström and Johansson Sundler2015), it was similarly the female participants who commented on this encroaching sense of daytime loneliness more than the men. By contrast, the solitude experienced by (the smaller number of) men we interviewed was often expressed in more positive terms as a part of their chosen lifestyle and offered continuity from their lives prior to diagnosis. This celebration of time alone may also point to the way that people become more comfortable in their own company as they age (Long and Averill, Reference Long and Averill2003) and that in some cases solitude may even foster a degree of wellbeing (Perlman and Peplau, Reference Perlman, Peplau, Gilmour and Duck1981; Larson, Reference Larson1990). Gendered differences in people's relationship to and coping with solitude when living with dementia may warrant further attention as a result of this insight. Previous research has looked at solitude or loneliness primarily from the perspective of women living alone with dementia within a domestic context and has not explored the wider world of neighbourhoods that hold social opportunities for people living alone with dementia as active citizens (deWitt et al., Reference deWitt, Ploeg and Black2009, Reference deWitt, Ploeg and Black2010; Frazer et al., Reference Frazer, Oyebode and Cleary2011; Lloyd and Stirling, Reference Lloyd and Stirling2011; Svanström and Johansson Sundler, Reference Svanström and Johansson Sundler2015). Our findings provide unique knowledge of the lived experiences of people living alone with dementia and their desire to sustain the social connections in their neighbourhoods and prevent social isolation in a neighbourhood context.

Limitations

In the context of this study, the majority of eligible participants were selected from the Swedish field site compared to the UK contingent so there is some weighting in our findings accordingly. The recruitment of the participants and outline for data collection differed between the UK and Swedish field sites, the order and type of data-gathering methods (detailed earlier) differed slightly between the two countries and, as a result, yielded different types of approach. In addition, there were also limitations to consider in terms of multiple researchers conducting the interviews in the three field sites that could influence our analysis, although the risk of discrepancies in our interpretation of the data was mitigated by one researcher (EO) leading the analysis and then subsequently checking their understanding with the wider team.

Implications for policy and practice

Our research adds new insights regarding how people living alone with dementia manage their neighbourhood-based social relations in ways that maintain their capacity to live independently in the community. A specific and more nuanced understanding of the social living conditions of single-householders with dementia is important in health and social care practice where service providers rarely look beyond the homogenising category of ‘people with dementia’ to consider some of the significant differences in people's living situations and capacity to manage their lives with dementia. Such awareness, of course, applies not least to a neighbourhood nursing perspective (Cumberlege, Reference Cumberlege1986) where nurses have to be aware of what life is like for community-dwelling people living alone with dementia (Keady, Reference Keady1994) and the crucial role that formal services and dementia practitioners can play in helping people to stay connected. This requires looking beyond the biomedical model that currently frames the care and treatment of individuals with dementia. But it is not only formal service providers that need to engage with this knowledge of life alone with dementia, there is an important and wider role to be played by the communities in which people reside. Businesses, retailers, local community hubs, and venues such as cafes, sports venues and transport facilities can play a role in helping people in their struggle to avoid isolation and the risk of loneliness (Alzheimer's Society, 2013; Age UK, 2018).

Hence, our findings can be used to inform the building of ‘dementia-friendly communities’ (Alzheimer's Disease International, 2016) where meaningful social networks and befriending from organisations is particularly essential for people living alone with dementia. In the key principles setting out how to develop dementia-friendly communities there is only one sentence about people living alone with dementia (Alzheimer's Disease International, 2016). This indicates that people living alone with dementia are currently largely unacknowledged in policy concerning dementia-friendly communities and specific actions need to be taken to ensure their voices are heard. A more direct focus on the needs of people living alone with dementia has to be acknowledged by the wider public, and local and national government, as this population increases worldwide. We all have responsibility as neighbours and citizens to support men and women living alone with dementia to remain citizens.

Conclusion

This study has built on previous evidence and insights regarding loneliness from the perspective of community-dwelling women living alone with dementia (deWitt et al., Reference deWitt, Ploeg and Black2009, Reference deWitt, Ploeg and Black2010; Frazer et al., Reference Frazer, Oyebode and Cleary2011; Lloyd and Stirling, Reference Lloyd and Stirling2011; Svanström and Johansson Sundler, Reference Svanström and Johansson Sundler2015). The value of relationships with neighbours for these women were highlighted as offering both practical and emotional support. The extent to which neighbourhoods hold social opportunities for people living alone with dementia has not been well explored in the existing literature, and this study therefore extends current knowledge by showing the importance of a lively and networked neighbourhood. In particular, we have shown that opportunities pursued by people living alone with dementia to stay engaged at a local level can help to prevent social isolation. Neighbourhoods are important because they provide a directly accessible arena for establishing new connections and maintaining existing relationships. Another insight that our study points to concerns gendered differences in people's relationships to and perspectives on solitude when living alone with dementia, which would benefit from further investigation. The situation of people living alone with dementia has to be better acknowledged in these early days of developing dementia-friendly communities. Our findings indicate that policy makers need to establish more opportunities for social meeting places in neighbourhoods which help to overcome generational divisions and increase knowledge about dementia. It is also urgent that interprofessional neighbourhood-based support and providers collaborate better in order to support the social connections of individuals who live alone. For instance, an individual named worker could play a vital role in helping to map and co-ordinate the networks to which people belong, supporting people to both maintain connections and foster new relationships in the face of social losses. Finally, people living alone with dementia were active agents who took initiatives and developed spontaneous encounters and strategies by themselves to stay connected locally and challenge the threat of isolation in the neighbourhood. This insight into people living alone with dementia as active agents in their neighbourhoods could therefore be of interest for further research and in development of dementia-friendly communities. Ultimately, our research points to the need for policy makers and service providers to consider the implications of the differing social and environmental situations of people living alone with dementia. A litmus test for emerging dementia-friendly community initiatives will be the extent to which those who live alone with the condition are enabled to thrive and participate in their local communities alongside their peers and neighbours.

Acknowledgements

The authors are sincerely grateful to the people living alone with dementia who participated in this study, and special thanks to the health-care staff and third sector who helped with the recruitment of participants. We are grateful to Barbara Graham for her dedicated work for the Scottish field site.

Author contributions

EO led the writing of this study, designed and led the analysis, and conducted data collection for the Swedish field site; AK was leader for the Swedish field site, conducted data collection and was involved in all stages of this study; IH proposed the idea for this study and gave guidance overall; AC co-designed the N:OPOP project and was work programme deputy, and leader for the English field site, as well as conducting data collection; SC conducted data collection and contributed with information about the participants from England; KM conducted data collection and gave information about the participants in Stirling; KR is mentor to the project leader; JK is mentor for the whole project team and Chief Investigator of the Neighbourhoods study, and co-designed the N:OPOP project; RW is Principal Investigator and co-designer of the N:OPOP project, and was involved in all phases of the study and the writing of this study. All authors have commented upon and/or given their approval for the final version of the article.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Swedish Riksbankens Jubileumsfond (grant number M10-0187:1); the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC); and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The research forms part of Work Programme 4 of the ESRC/NIHR Neighbourhoods and Dementia mixed-methods study (reference ES/ L001772 /1; www.neighbourhoodanddementia.org).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Ethical standards

Ethical approval was obtained from the NHS Health and Social Care Research Ethics Committee in the UK (reference 15/IEC08/0007) and the Regional Ethical Review Board in Linköping (county of Östergötland, Sweden) (reference 2013/200-31 and 2014/359-32).