Introduction

In Australia and other western societies, older people rely heavily on the private car as their primary mode of transport (Buys et al., Reference Buys, Snow, van Megen and Miller2012; Cui et al., Reference Cui, Loo and Lin2017; Gormley and O'Neill, Reference Gormley and O'Neill2019). For many older people, driving is key to maintenance of mobility (King et al., Reference King, Meuser, Berg-Weger, Chibnall, Harmon and Yakimo2011) and quality of life (Oxley and Whelan, Reference Oxley and Whelan2008; Musselwhite and Haddad, Reference Musselwhite and Haddad2010). Driving also provides a sense of freedom, control, identity, independence and social connectedness (Windsor et al., Reference Windsor, Anstey, Butterworth, Luszcz and Andrews2007; Musselwhite, Reference Musselwhite2017; Pristavec, Reference Pristavec2018; Sanford et al., Reference Sanford, Naglie, Cameron and Rapoport2020; Ang et al., Reference Ang, Jennifer, Chen and Lee2019a).

In the coming years, it is predicted the reliance on private cars by older people as the main form of transport will increase (Haustein and Siren, Reference Haustein and Siren2015) in line with the projected ageing population (United Nations, 2019). However, older drivers need to consider alternatives to driving, as previous research suggests they will live seven to 10 years beyond their driving life (Foley et al., Reference Foley, Heimovitz, Guralnik and Brock2002). Expectations of driving life by some older people, however, differ from this reality. One study reports that one in ten older drivers never intend to stop driving and over half intend to stop driving when they are in their nineties (Naumann et al., Reference Naumann, West and Sauber-Schatz2014). A more recent study found that 10 per cent of older drivers expect to stop driving near their death (Babulal et al., Reference Babulal, Vivoda, Harmon, Carr, Roe and Zikmund-Fisher2019). However, it was also reported older people expect to live on average nearly six years, with some reporting up to 30 years, post driving retirement (Babulal et al., Reference Babulal, Vivoda, Harmon, Carr, Roe and Zikmund-Fisher2019). Therefore, it is important that older drivers are able to recognise and consider future driving retirement and alternate mobility options.

Deciding on the ‘right’ time to retire from driving is challenging, particularly given the individual variations in the degree of cognitive and physical health decline people experience as they age (Andrew et al., Reference Andrew, Traynor and Iverson2015; World Health Organization, 2015; Pomidor, Reference Pomidor2019). On the one hand, guidelines and reports support maintenance of driving because it provides an important way that older people can maintain mobility and out-of-home activities which contribute to improved health and quality of life (Musselwhite and Haddad, Reference Musselwhite and Haddad2010; Baldock et al., Reference Baldock, Thompson, Dutschke, Kloeden, Lindsay and Woolley2016; Parkes, Reference Parkes2016). This approach is important as the loss of driving privilege increases the risk of depression (Chihuri et al., Reference Chihuri, Mielenz, DiMaggio, Betz, DiGuiseppi, Jones and Li2016) and associated with declines in life satisfaction, social participation and increased mortality risk (Liddle et al., Reference Liddle, Gustafsson, Bartlett and Mckenna2012; Chihuri et al., Reference Chihuri, Mielenz, DiMaggio, Betz, DiGuiseppi, Jones and Li2016; Pristavec, Reference Pristavec2018). On the other hand, older drivers are disproportionately represented in car-related serious injuries and fatalities (Ang et al., Reference Ang, Chen and Lee2017), attributed to their increased frailty (Baldock et al., Reference Baldock, Thompson, Dutschke, Kloeden, Lindsay and Woolley2016; Pomidor, Reference Pomidor2019). In the absence of a validated office-based test to assess fitness to drive (Dickerson et al., Reference Dickerson, Meuel, Ridenour and Cooper2014; Pomidor, Reference Pomidor2019), some jurisdictions implement controversial age-based licencing renewal policies to address safety concerns (Kahvedžić, Reference Kahvedžić2013; Siren and Haustein, Reference Siren and Haustein2015). Opponents of mandatory aged-based on-road assessments or medical reviews for older drivers argue such policies provide no or limited safety benefits, are ageist and discriminatory, are not evidence based or work against maintaining independent mobility (Tasmanian Department of Infrastructure, Energy and Resources, 2011; Kahvedžić, Reference Kahvedžić2013; Siren and Haustein, Reference Siren and Haustein2015).

Regardless, some older people will need to retire from driving due to health declines. To attenuate the negative effects of driving retirement, various countermeasures are hypothesised and can be grouped into three categories. First, maintaining participation in social activities post driving retirement is central to preserving positive mental health (Pachana et al., Reference Pachana, Leung, Gardiner and McLaughlin2016). Second, older drivers who engage support networks that provide advice, emotional or practical social support can temper the drop in life satisfaction following driving retirement and maintain quality of life (Musselwhite and Shergold, Reference Musselwhite and Shergold2013; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Johnson, Borkoski, Rebok, Gielen, Soderstrom, Molnar, Pitts, Diguiseppi, Hill, Strogatz, Mielenz, Betz, Kelley-Baker, Eby and Li2019). Third, as early planning is a strong predictor of higher self-reported quality of life post driving retirement (Musselwhite and Shergold, Reference Musselwhite and Shergold2013), regular discussions and early planning to emotionally and logistically prepare older drivers for life without driving are highly recommended (Baldock et al., Reference Baldock, Thompson, Dutschke, Kloeden, Lindsay and Woolley2016; Pomidor, Reference Pomidor2019).

Discussions and planning for driving retirement

Discussions about driving are important as they ‘plant the seed’ (Betz et al., Reference Betz, Jones and Carr2015: 235) for older people to think about changes early in the decision pathway instead of driving retirement being sudden or forced (Betz et al., Reference Betz, Scott, Jones and Diguiseppi2016). Despite older people's preference to be central to decisions about driving (Betz et al., Reference Betz, Scott, Jones and Diguiseppi2016), few ever report having planned or discussed driving retirement with their support networks such as health practitioners or family (Betz et al., Reference Betz, Villavicencio, Kandasamy, Kelley-Baker, Kim, DiGuiseppi, Mielenz, Eby, Molnar, Hill, Strogatz, Carr and Li2019). Health practitioners find discussions with older drivers challenging for a range of reasons. These include gaps in training on driving assessments and counselling, inadequate resources on the topic, time constraints, or concern over negatively affecting the doctor–patient relationship when recommending an unfavourable outcome from the perspective of the older person (McKernan et al., Reference Mckernan, Chia, Traynor, Veerhuis, Mcneil and Pond2022; Betz et al., Reference Betz, Jones, Petroff and Schwartz2013, Reference Betz, Jones and Carr2015).

Rural medical practitioners are significantly less likely to discuss driving with people over 75 years compared to their urban counterparts (Huseth-Zosel et al., Reference Huseth-Zosel, Sanders, O'Connor, Fuller-Iglesias and Langley2016). This is due to inadequate resources, feeling responsible for the older person losing independence and distance to the nearest on-road driving assessment (Huseth-Zosel et al., Reference Huseth-Zosel, Sanders, O'Connor, Fuller-Iglesias and Langley2016). Research with adult children of older drivers attribute avoidance of discussions about driving to the perceived personal burden of immobile older parents and denial, by the parent, of declining driving skills (Connell et al., Reference Connell, Harmon, Janevic and Kostyniuk2013).

Avoidance of discussions and planning about driving is not restricted to medical practitioners and family. Older drivers themselves rarely discuss or plan for driving retirement, even if they believe that planning would assist in the transition to driving retirement (King et al., Reference King, Meuser, Berg-Weger, Chibnall, Harmon and Yakimo2011; Harmon et al., Reference Harmon, Babulal, Vivoda, Zikmund-Fisher and Carr2018; Betz et al., Reference Betz, Villavicencio, Kandasamy, Kelley-Baker, Kim, DiGuiseppi, Mielenz, Eby, Molnar, Hill, Strogatz, Carr and Li2019). Those who do plan are typically older, live alone, do not view driving as important, are not confident drivers or have received medical advice after a ‘red flag’ event such as a car accident or medical event (Betz et al., Reference Betz, Jones, Petroff and Schwartz2013: 1575; Harmon et al., Reference Harmon, Babulal, Vivoda, Zikmund-Fisher and Carr2018; Feng and Meuleners, Reference Feng and Meuleners2020). However, even for older people who do plan, few make any practical life changes to prepare themselves for life without driving (Feng and Meuleners, Reference Feng and Meuleners2020). The reasons for avoiding discussions and planning for driving retirement are yet to be explored fully from the perspective of the older person.

Theoretical framing

Prior research reveals differences between how younger and older people make decisions (Löckenhoff, Reference Löckenhoff2018). Models of decision making that take into consideration the age of the decision maker therefore represent an ideal framework to underpin our investigation of driving retirement decisions by older people. Previous studies which are underpinned by aged-based and lifespan theories such as socioemotional selectivity theory (Carstensen et al., Reference Carstensen, Isaacowitz and Charles1999) and the selection, optimisation and compensation model (Baltes and Baltes, Reference Baltes, Baltes, Baltes and Baltes1990) provide valuable insight to understanding the impact of driving retirement on the social engagement of older people (Qin et al., Reference Qin, Tuschman and Wang2020) and older driver self-regulation strategies (Bieri et al., Reference Bieri, Nef, Müri and Mosimann2015). Yet to be explored is how aged-based decision theories develop our understanding of the decision-making process of older drivers discussing and planning for driving retirement. By adopting a decision-making theoretical perspective specifically for older people, the present study provides new insights to understand the decision-making process associated with discussions and planning for driving retirement.

The ageing and decision-making framework proposed by Löckenhoff (Reference Löckenhoff2018) integrates numerous theories across various disciplines to explain age differences in decision making (Figure 1), and therefore an ideal framework to explore the topic of driving retirement for older people. Alternative models exploring older people and driving retirement are typically underpinned by wellbeing theory or do so in the context of mobility more broadly (Nordbakke and Schwanen, Reference Nordbakke and Schwanen2014; Musselwhite and Haddad, Reference Musselwhite and Haddad2018).

Figure 1. Conceptual framework for mapping age differences in decision making.

Source: Löckenhoff (Reference Löckenhoff2018: 141). Copyright © 2017 Karger Publishers, Basel, Switzerland.

The ageing and decision-making framework (Löckenhoff, Reference Löckenhoff2018) identifies cognitive, affective and motivational mechanisms (shown in the top white box in Figure 1) impact decision-making processes for older people (shown in the bottom white box in Figure 1) (Löckenhoff, Reference Löckenhoff2018). Cognitive decline, typical with increasing age, can impair memory and processing speed, which can, for example, impact pre-decision information search and planning skills (Löckenhoff, Reference Löckenhoff2018; Tannou et al., Reference Tannou, Koeberlé, Aubry and Haffen2020). Consequently, older people may need additional time to make decisions and will rely upon their past experiences for decisions that need to be made quickly (Löckenhoff, Reference Löckenhoff2018; Tannou et al., Reference Tannou, Koeberlé, Aubry and Haffen2020).

However, as Figure 1 also illustrates, older people can draw upon affective and motivational mechanisms which can compensate for such cognitive decline (Löckenhoff, Reference Löckenhoff2018). Affect, such as positive and negative emotions, can influence the decisions older people make. There can be a tendency for older people to rely on positive affective responses when making decisions, particularly for complex decisions, which can lead to biases (Löckenhoff, Reference Löckenhoff2018; Tannou et al., Reference Tannou, Koeberlé, Aubry and Haffen2020). For example, older people may be more inclined to pursue more positive rather than negative material when weighing options, seeking information and making decisions (Reed et al., Reference Reed, Chan and Mikels2014; Löckenhoff, Reference Löckenhoff2018). Motivational mechanisms which impact decision-making processes for older people include having perceived limited time horizons (socioemotional selectivity theory) compared to younger counterparts (Carstensen, Reference Carstensen1995). Older people therefore may be inclined to make decisions which are rewarded with outcomes that are more emotionally positively fulfilling in the short term (Carstensen, Reference Carstensen1995).

The task characteristics of the decision being made and contextual factors (middle two white boxes in Figure 1) also impact how older people make decisions (large white box at the bottom of Figure 1) and the outcome of the decision (Löckenhoff, Reference Löckenhoff2018). For example, decisions that hold higher accountability or personal importance typically involve more deliberation and engagement in information search strategies when deciding between choices (Hess et al., Reference Hess, Queen and Ennis2013). Contextual factors (right middle white box in Figure 1), including the social context of the decision and support networks, also play a key role in how older people make decisions (Löckenhoff, Reference Löckenhoff2018).

In general, older people more often avoid engaging in decisions compared to younger cohorts. Differences occur with decision identification, engagement, delegation and information search in response to task characteristics, context, cognitive, motivational and affective mechanisms (Löckenhoff, Reference Löckenhoff2018).

Aims and research questions

This study aimed to contribute knowledge regarding how decisions to discuss or plan for driving retirement occur among older people. This was achieved by answering the following research questions.

(1) What are the perceived barriers to discussing and planning for driving retirement among older people?

(2) What are the perceived facilitators to discussing and planning for driving retirement among older people?

Method

Study design

This study employed a qualitative design involving face-to-face interviews with older drivers (Polit and Beck, Reference Polit and Beck2004). This approach enabled an in-depth understanding of the views and experiences of older people about driving retirement (Polit and Beck, Reference Polit and Beck2004). The themes are interpreted and discussed within the context of Löckenhoff's (Reference Löckenhoff2018) ageing and decision-making framework (Figure 1). Ethics approval to conduct the present study was obtained from the University of Wollongong prior to data collection commencing.

Participants and recruitment

A convenience sample of 43 older drivers, 65 years and over, and residing in the state of New South Wales (NSW), Australia, were recruited through contacts known to the research team (Polit and Beck, Reference Polit and Beck2004). The sample necessarily included older drivers, as the aim of the research was to understand discussions and planning for driving retirement from the perspectives of older people. We contacted participants by email and invited them to be interviewed. We provided participants with an information sheet and consent forms were signed prior to the interviews commencing. Sample diversity in terms of participants' geographical location, age and gender were considered to capture as wide a range of views as possible. Sample diversity on these dimensions was important because they are known to impact the decisions of older people about driving retirement (Ang et al., Reference Ang, Oxley, Chen, Yap, Song and Lee2019b). The geographic locations of participants were categorised according to the Modified Monash Model, which measures geographic area relative to access to public services (Australian Government Department of Health, 2019).

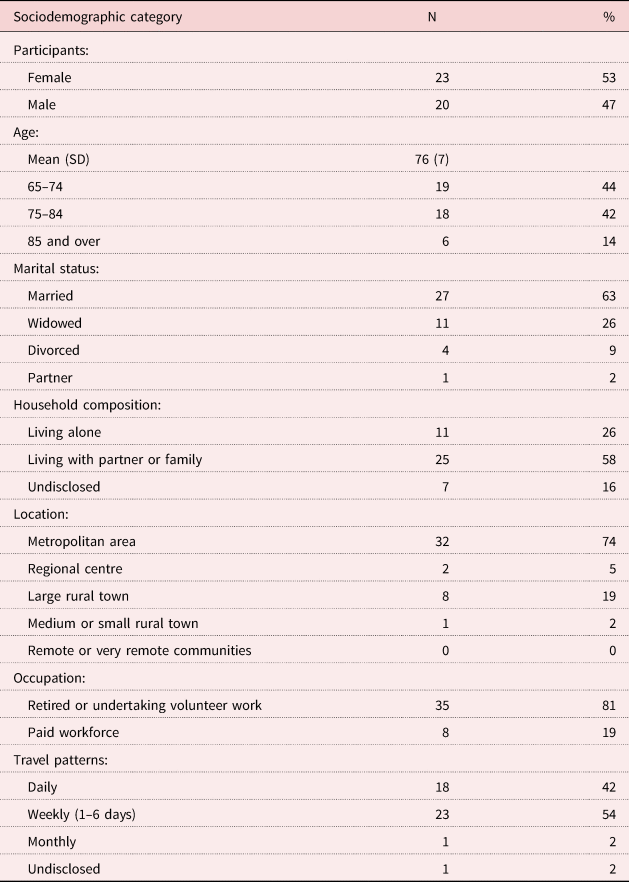

Details of the sample characteristics are provided in Table 1. Most participants lived with a partner or family member (N = 25, 58%). Daily (N = 18, 42%) or weekly (N = 23, 54%) driving patterns were reported with mean driving experience of 55 years (standard deviation (SD) = 6). Just over half of participants were female (N = 23, 53%) and almost three-quarters lived in metropolitan areas (N = 32, 74%). The mean age of participants was 76 years (SD = 7).

Table 1. Participant characteristics

Notes: N = 43. SD: standard deviation.

Data collection

Semi-structured interviews were conducted over a three-month period in 2019. Interviews ranged from 20 to 120 minutes in duration and were conducted at a place chosen by the participants at a mutually convenient time. Audio recordings were transcribed verbatim. The interview schedule consisted of sociodemographic and pre-defined semi-structured questions relating to experiences, meaning and memories of: driving in the past, driving in the present, being a passenger, perceptions of life without driving, discussions about cars and driving, and costs and decisions associated with buying and owning a car.

Data analysis

Demographic profiles of participants were descriptively analysed using Microsoft Excel, version 16. Analysis of interview transcripts was conducted using NVivo 12 software (QSR International, Melbourne). Thematic analysis was guided by the steps of Braun and Clarke (Reference Braun and Clarke2006) using an inductive data-driven approach. Thematic analysis is used to describe and interpret recurring themes and patterns across data and to summarise key features of large datasets (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). Unlike alternative analytic approaches like interpretative phenomenological analysis, thematic analysis provides theoretical flexibility to understand the perspectives of older people in the context of driving retirement and therefore was considered a suitable analytical method to answer our research questions (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006).

The analysis process involved an initial familiarisation with the interviews by listening to three audio recordings and reading the transcripts to identify initial codes. Each transcript was then read and worked through systematically to code the data. Next, the full dataset was reviewed, codes refined and new codes identified. In the final step, after iterative reviewing of codes was complete and no new codes identified, themes and subthemes were generated (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). These themes and subthemes were then reflected upon and refined, again using an iterative process across the dataset (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). A table with corresponding participant quotes which exemplify the themes was then developed and reviewed by members of the research team until consensus about their appropriate assignment to themes was reached.

Findings

Understanding discussions and planning for driving retirement

Most participants had not thought about, discussed or planned for driving retirement prior to the interview. As one participant stated:

No, actually I haven't discussed ‘not driving’ with family or friends. No, it is an issue that I haven't discussed. (Male, 74, metropolitan area)

Except for their early years, most participants had none or very few experiences of life without driving. The few experiences of life without driving were temporary, for example, a short period of time due to an operation or for a few days when a car was being repaired or serviced. Notably, in our study there were a few participants who had adopted alternative modes of transport in addition to using the car. One participant felt confident dealing with the transition process because she:

Could manage quite well, cause I'm pretty independent without a car. I've already got the buses, the taxis … and maybe a girlfriend. (Female, 68, metropolitan area)

These individuals felt this helped them feel prepared for the transition to life without driving. The main findings reported in this study are provided as a thematic summary, describing the barriers and facilitators to discussing and planning for driving retirement by older drivers.

Barriers to discussing and planning for driving retirement

Theme 1: Negative perceptions

When asked about plans for a future without driving, older drivers conveyed a range of negative emotions and implications. Loss, change and death were outcomes typically associated with life without driving. Both males and females of different ages expressed negative emotions when thinking about discussing and planning for driving retirement. No one looked forward to life without driving, as participants felt that no other transport alternatives could replace the benefits provided by driving their own car. While this broad sentiment was expressed by all participants, the specific benefits they were concerned about losing were expressed in different ways. One participant stated:

When it's a nice sunny day and I'm in a good mood I love to jump in the car and go up to one of the northern beaches perhaps, or down the coast a bit and you know, just somewhere nice, so you're always relaxed and happy in the car. (Male, 67 metropolitan area)

Some participants expressed this view in terms of the ability to be spontaneous and decide where to go on the day, for example, according to the weather outside. Some explained that driving offered them a level of convenience that they did not think they would get from other forms of transport. Others explained that they found the experience of driving, and the independence this offered them, enjoyable.

Loss

For many older drivers in this study, the loss of driving privileges represented a loss of independence, freedom, convenience and the ability to do things for themselves. As one driver described:

…you've lost the biggest thing in your life, which is your own independence at 80 or 75. (Female, 75, large rural town)

The loss of driving privilege means loss of spontaneity and doing the things you want ‘whenever I want to and not have to rely on timetables’ (Female, 75, large rural town). Loss of convenience and time was also connected to driving retirement. Using alternative transport options required additional time and preparation while driving did not. This was the case even in metropolitan areas. As one participant explained:

It's not just expensive, you need more time, you need to wait for the bus, you need to wait for the taxi. (Female, 68, metropolitan area)

Loss of important social and leisure activities was also anticipated with driving retirement. One participant reflecting on the prospect of driving retirement stated: ‘I might have to give up my sporting, my golf’ (male, 66, metropolitan area). This is because the car offers, for example, the ability to transport equipment required to maintain leisure activities.

Change

Loss and change are intertwined as the loss of driving privilege brings a change to the current way of life, including how participation in social and leisure activities occurs. One participant describes the anticipated changes to everyday activities:

I couldn't jump on a bus to go to golf because I've got so much gear with me … if I had to go shopping and I had to buy a lot of stuff, I'd probably have to get a taxi with all the bags and things. (Male, 66, metropolitan area)

Others describe the need to relocate if they can no longer drive. This is particularly notable for those living in rural areas, as one participant describes: ‘If we couldn't drive, we wouldn't be able to live up there’ (Female, 71, large rural town). These expected changes as a result of driving retirement were not something participants looked forward to as driving embodied more than a means of transport for most, although not all participants. The importance of driving a car was described by one participant as ‘part of life you know. Once you lose that, things will change’ (Male, 73, metropolitan area). Conversely, for others, driving was not an enjoyable experience and merely a means to get from one place to another. Still, most participants anticipated emotional and mental health changes such as anxiety or depression upon the loss of driving privileges. Furthermore, participants described physical responses, such as feeling sick, at the thought of life without driving.

Symbolising death

Planning for driving retirement is inextricably linked to death for some older drivers. The complete loss of driving privilege symbolised death or approaching end-of-life and, for this reason, it was difficult to discuss or prepare for life without driving. As one female participant described:

To prepare yourself for a death? It's just the same as a death, you ask anybody. (Female, 75, large rural town)

Further, driving retirement was perceived as an event expected near death. Therefore, preparing or planning for driving retirement was difficult as the timing of death was uncertain; for example:

To make a decision about a date from which I then am not going to drive, presupposes that you have a good idea about your mortality, and what is going to hold for you in the future. (Male, 68, metropolitan area)

Older drivers also explained they consciously avoided contemplating, discussing or planning for driving retirement. As one participant explains, it is:

Like the chicken's last walk to the woodheap (laughing). If you've lost your licence you must be running out of living time, and it's not something that people want to actually face up to. (Female, 77, metropolitan area)

Older drivers, therefore, do not want to think about or make plans for driving retirement as they do not want to plan or discuss end-of-life.

Theme 2: It's not my time

A group of older drivers, which included both males and females across all age groups and different geographic locations, considered driving retirement not an imminent event and therefore it was not ‘time’ to discuss or plan for a future without driving. Imminent was described by older drivers in terms of timeframes including ‘today’, ‘tomorrow’, in ‘one or two years time’. As one older driver explained:

The fact is that [driving retirement] is so far off I believe that it's never been a discussion point. (Male, 71, metropolitan area)

The reasons participants considered that it was not their time to discuss or plan for driving retirement was based on observations they had made of drivers older than themselves who continued to drive successfully, their self-perceived good health and their confidence in their own driving abilities. For these reasons, discussions and planning for driving retirement did not occur.

Observation of others

Older drivers observed people older than themselves continuing to drive into their eighties and nineties. This observation reinforced the ‘possibilities’ of maintaining driving privileges long into the future. One male driver commented:

I'm 73. I mean, look, we just don't know. I would like to think I can continue to drive for a long time yet. I mean, we have a lady in our bible study, [she] is 88. (Male, 73, metropolitan area)

Participants suggested that driving would continue up until the end of life as this was observed in others close to them. One male driver described his observations of others close to him: ‘[My wife's] father, 94, and he still drives and passes his driving test.’ Another older person states that:

My father died at 87 and he had just passed his driving test and they're both good drivers and nobody, neither of those men thought or had made a thought about what would happen if they couldn't drive. (Male, 68, metropolitan area)

For this reason, there was no need to consider life without driving.

Perceived good health

Perceived good health is a further reason driving retirement was not considered or discussed:

Mentally okay, physically okay, medically, reasonably okay. I think I'm fairly alert. I think I am a reasonably good driver, so I haven't really talked about that. (Male, 73, metropolitan area)

This reflection by a driver described how his current health influenced his decision not to discuss driving retirement.

Self-awareness of changes in one's health and body were considered an important attribute to identifying the timing of discussions and decisions about driving retirement. For example, a female driver in a rural town revealed:

You know in yourself. My health is pretty good … so you know, I just never thought of it … you know your own body, if you can do it or you can't. (Female, 75, large rural town)

Other drivers had contrary experiences:

I'm still active enough to walk to the station but there'll become a time where I won't be able to walk to the station, and then the car will be more important while I maintain my independence. (Male, 65, metropolitan area)

For some, driving as a mode of transport was perceived to become even more important with declines in physical ability.

Confidence in driving ability

Participants who felt confident and comfortable in their driving ability, were less likely to discuss or plan for driving retirement. One male driver suggested changes to his perceived ‘feelings’ about driving ability would facilitate contemplation of driving retirement.

…because I feel good enough to drive. If I didn't feel good enough for driving, then I would have to think about retiring from driving. (Male, 76, metropolitan area)

Irrespective of age and geographical location, feeling confident in one's driving ability is equally attributed to why discussions and planning for driving retirement were not considered, as one participant explained: ‘I just don't think about it, while I'm feeling confident in driving’ (Female, 84, regional centre). Confidence and comfort in current driving ability meant that driving retirement was not expected to occur in the short term, therefore discussions were unnecessary:

I don't need to talk about it because I'm still comfortable driving. I'm not sort of intending on giving up driving in the next twelve months. (Female, 75, large rural town)

Others expected their driving ability to be maintained over time:

I haven't thought about it because the simple reason being that I know that at 85 I have to go for a test, but I feel confident enough that I'm a good enough driver that I will be able to pass that. (Male, 71, metropolitan area)

For this driver, he expected his driving skills would remain unchanged for more than ten years.

Theme 3: Denial

Most participants had not considered life without driving before the interview took place. Denial of the need to discuss or plan for driving retirement was identified by participants of both genders and from a range of geographic locations. As one male participant on the topic of discussing driving retirement declared: ‘Well … as far as I'm concerned, it's taboo!’ (Male, 78, metropolitan area). Indicators of denial included older drivers not being able to imagine or foresee a life without driving; they did not want to think about driving retirement or preferred to wait until it ‘just happened’.

Can't imagine it

Driving was viewed as an integral part of everyday life by most participants:

We at our age are dealing with something we have lived with all our lives and that's how you see the future. If the future is different, I don't know. (Male, 68, metropolitan area)

Another driver explained: ‘At this stage you can't ever envision not driving’ (Male, 73, metropolitan area). Similarly, a female driver reflected that:

I have not got any plans! I've never thought of not being able to drive, it's just something that is second nature … never talked about not having a car and never thought about it. (Female, 77, metropolitan area)

For these drivers it was difficult to imagine a life without driving.

While for other participants because they anticipate they would never stop driving, discussions and planning for driving retirement were not required. As one participant explains:

You can't see it happening … you never think you're gunna [sic] get to the point where you can't drive, so you don't even think about it. (Male, 68, metropolitan area)

Furthermore, some participants cannot imagine a time where their driving skills or health may decline as: ‘We think we are invincible. We think we are going to be driving for ever’ (Female, 81, metropolitan area). As driving retirement is perceived as an event that would never occur at any point in time, it was not something even considered. Consequently, discussions and planning do not occur.

Don't want to think about it

Many older people preferred not to think about life without driving with preference for maintaining the status quo. This preference was due to the perceived negative consequences that would occur upon driving retirement. One participant described a perceived uncertain future upon retiring from driving:

I don't know what the future is going to bring it's not going to be fun. I don't want to talk; I don't want to think about it right now … when you get old you don't want to think too much ahead, so at the moment, I'm happy the way things are. (Female, 76, regional centre)

Another driver provides specific consequences and fears of change as reasons for not thinking about driving retirement, suggesting:

No, I don't want to think about it. I'd hate it. If I live long enough, I suppose it will come. I don't want to leave my house you see; I don't want to go into one of those old people homes. (Female, 81, metropolitan area)

Some older drivers accepted driving retirement as an inevitable event in the future. For example, a female driver explained:

Well you know it's [going to] happen, but you don't think about it. Or you think about it and you put it out of your mind. (Female, 75, large rural town)

Even for drivers who were accepting of a non-driving future, it was preferrable not to think that this event was ahead of them.

Will wait until it happens

Some participants indicated a preference for waiting until driving retirement is a forgone conclusion before discussions and planning for driving retirement occur. The practical adjustment required for life without driving would also be made at this time. As one driver explains:

I think when I can't drive, I'll just accept the fact that I can't drive, and I'll have to rely on public transport. (Female, 75, large rural town)

Furthermore, decisions to defer discussions and planning until the time of driving retirement were based on observations of other older adults who also did this:

They [parents] were going to wait till it happened and then worry about it. That's why I say I don't think anyone can answer that [about plans for driving retirement]. (Male, 68, metropolitan area)

There were also older people who just did not want to make plans about changing driving habits or retiring from driving.

Facilitators to discussing and planning for driving retirement

Theme 1: Intrinsic influences

Despite most participants not having considered life without driving, various situations and triggers were identified which may prompt older drivers to contemplate, discuss or plan for driving retirement in the future. Declines in physical and cognitive health, age and declining driving confidence were intrinsic contributors prompting discussions about changes to driving behaviour in the future.

Declines in physical and cognitive health

Declines in physical and cognitive health were perceived triggers for contemplating changes to driving behaviour in the future. As one participant stated, when asked about their plans to retire from driving:

Depends on my health, if I'm healthy, I'm going to drive to 101. If not, I'm going to choose something else. (Female, 68, metropolitan area)

Specifically, declines in cognition and vision were potential triggers to discussions and contemplation about changes in driving behaviour. This was the case for one male older driver, who suggested discussions would occur: ‘Not until my eyesight or brain goes’ (Male, 65, metropolitan area). When asked if there were any plans for driving retirement, one participant responded:

Obviously that is something that eventually is going to happen [driving retirement]. I wouldn't stop unless there was medical reasons for my doing so. (Female, 75, metropolitan area)

It was clear that for some older people driving retirement would only be considered if they experienced a medical problem.

Age

Age was perceived as a trigger prompting plans to manage future mobility options. For example, one male driver explains he will rely on his wife who is younger than him to drive when he is unable to:

Initially my wife, because she's about 5 years younger than me, so in theory she might be driving for some years after I'm not able to. (Male, 65, metropolitan area)

The specific age in which planning for driving retirement would occur differed between participants. For example, one driver aged 80 had no plans despite acknowledging driving retirement will occur at some point:

At the moment I'm not planning to give up driving, no. As I said, I'm 80, I know it's going to happen. (Male, 80, metropolitan area)

However, perceptions about the specific age discussions and planning would occur changed for some participants as they reached closer to that age. For example, one participant explains:

I thought that was ridiculous that people were still driving their car when they were 90. I just couldn't imagine ever being 90. So, I suppose I thought that people driving at 80 was ridiculous too … but now that I'm 90 I can't see why I can't drive. I don't feel any different. (Female, 92, large rural town)

Therefore, for some participants, how they felt about their health and driving skills was viewed as more important than the pre-determined age that participants would plan for driving retirement.

Decline in confidence

Reduced confidence in driving ability was also identified as a trigger that would prompt participants to consider having a discussion or plan for driving retirement. Participants indicated they would rely on personal judgement to identify declines in driving abilities. One female driver explains: ‘Well, hopefully I'll have enough common sense to know that I'm not capable’ (Female, 71, large rural town). Driving retirement would only occur at the point at which participants determined their own capacity to drive safely was compromised. A male driver living in a small rural town revealed:

I think sometimes you're an idiot for worrying about it because you're still good on the road. And if I thought I wasn't I would give my licence back, so I know that for a fact. (Male, 66, metropolitan area)

Those older drivers who self-identified as experiencing declines in driving confidence purposely changed when and where they drove, for instance avoiding night driving.

Theme 2: Extrinsic influences

Changes to life circumstances such as relocation or retirement, compulsory driving medical assessments, medical advice or a car accident were extrinsic factors that may prompt discussion and planning for life without driving.

Changes to life circumstance

Despite most participants having no plans for driving retirement, there were plans for other life changes such as retiring from work or relocating residence. Transport options were sometimes considered by older drivers in these plans. One participant provided an example of how decisions about relocating included plans for future transport options:

Well we have bought our final home and have made sure it's on a bus line and close to public transport and hospitals so that transport will never be an issue because we have thought about that in retirement. (Female, 67, metropolitan area)

Downsizing place of residence was considered an opportunity to plan for future changes to driving behaviour and alternative modes of transport. As an example, one participant explained:

At this point, there is [sic] no plans, but it doesn't have to be. But we're talking now, [my wife] is desperate to downsize. (Male, 76, metropolitan area)

Another participant identified involvement in the aged care system as a trigger for planning:

Being in the system of the retirement system and getting into the aged care, well you're covered pretty well … if I ever need to fall back on them, I've got them. (Female, 89, metropolitan area)

Being part of the aged care system for this person started the process to secure future accommodation and transport needs when the time came to retire from driving.

Compulsory medical assessments or medical advice

Compulsory annual medical assessments and an on-road test were specific events that may lead some older drivers to discuss or plan for driving retirement. Older drivers were aware of licence renewal requirements, including medical assessments and on-road tests, however, there was uncertainty by some older drivers of the age this occurs. As one driver commented:

No, not at this age. I think in 5 years’ time, I'll be 78. I think after you turn 80, you have to get a [on-road] test every year. I'm not sure. (Male, 74, metropolitan area)

Letters sent from the driver licensing authority to complete the compulsory annual driving medical assessments prompted some older drivers to contemplate discussions about driving retirement. For example, one participant commented:

It hit me when my sister-in-law got a letter and I got a letter to take it to the doctor. (Female, 75, large rural town)

For one female driver, it was not until the on-road driving test that an open discussion about driving and the test process occurred:

I did talk a lot about it. But when I was going to go for my test again, yeah (laughs), just sort of more, of you know reassurance more than anything. (Female, 85, metropolitan area)

A driving test for this older woman, however, did not lead to a discussion about driving retirement.

Medical advice was viewed as a compelling reason for when discussions and decisions to cease driving would occur. One participant identified preference to defer discussions and delegate the final decision about driving retirement to the medical doctor, pointing out that:

There [sic] nothing much we can do about it, the doctor says no, you're not going to be able to, you don't. (Female, 75, large rural town)

Older drivers were also accepting that medical issues that would impact driving skills would arise at some stage:

Obviously that is something that eventually is going to happen [driving retirement], I wouldn't stop unless there was [sic] medical reasons for my doing so. (Male, 85, metropolitan area)

Medical problems were therefore seen as a legitimate reason to stop driving.

Car accident

A small group of female participants identified car accidents, although unconvincingly, as a possible trigger for initiating discussions about driving retirement. As one participant explained: ‘If I had an accident, ...I wouldn't drive again, I don't think’ (Female, 71, small rural town). Concerns about having a car accident did facilitate older people to consider changes to their driving behaviour, such as avoiding intersections without traffic lights. For example, one participant states:

I've then got a lot of traffic on this road and I'm sort of thinking, well, I don't need to risk an accident, I'll just go with the lights. (Female, 67, metropolitan area)

Involvement in a car accident in conjunction with increasing age was an additional reason to consider driving retirement. As one participant describes: ‘I'm 71, so I just think then [if I had an accident] maybe it's time to give it up’ (female, 71, small rural area). Additionally, family members raising concerns about an increased risk of a car accident would also prompt older drivers to think about driving retirement.

Discussion

Older drivers rarely discuss or plan for driving retirement with health practitioners or family members (Betz et al., Reference Betz, Villavicencio, Kandasamy, Kelley-Baker, Kim, DiGuiseppi, Mielenz, Eby, Molnar, Hill, Strogatz, Carr and Li2019). Thus far, qualitative studies on discussions or planning for driving retirement from the perspective of the older driver are limited (Betz et al., Reference Betz, Jones, Petroff and Schwartz2013), are focused on health practitioners (Betz et al., Reference Betz, Jones and Carr2015) or are quantitative studies (Harmon et al., Reference Harmon, Babulal, Vivoda, Zikmund-Fisher and Carr2018; Betz et al., Reference Betz, Villavicencio, Kandasamy, Kelley-Baker, Kim, DiGuiseppi, Mielenz, Eby, Molnar, Hill, Strogatz, Carr and Li2019). This study qualitatively explored older driver perceptions about driving retirement to identify the barriers and facilitators to discussing and planning for a life without driving.

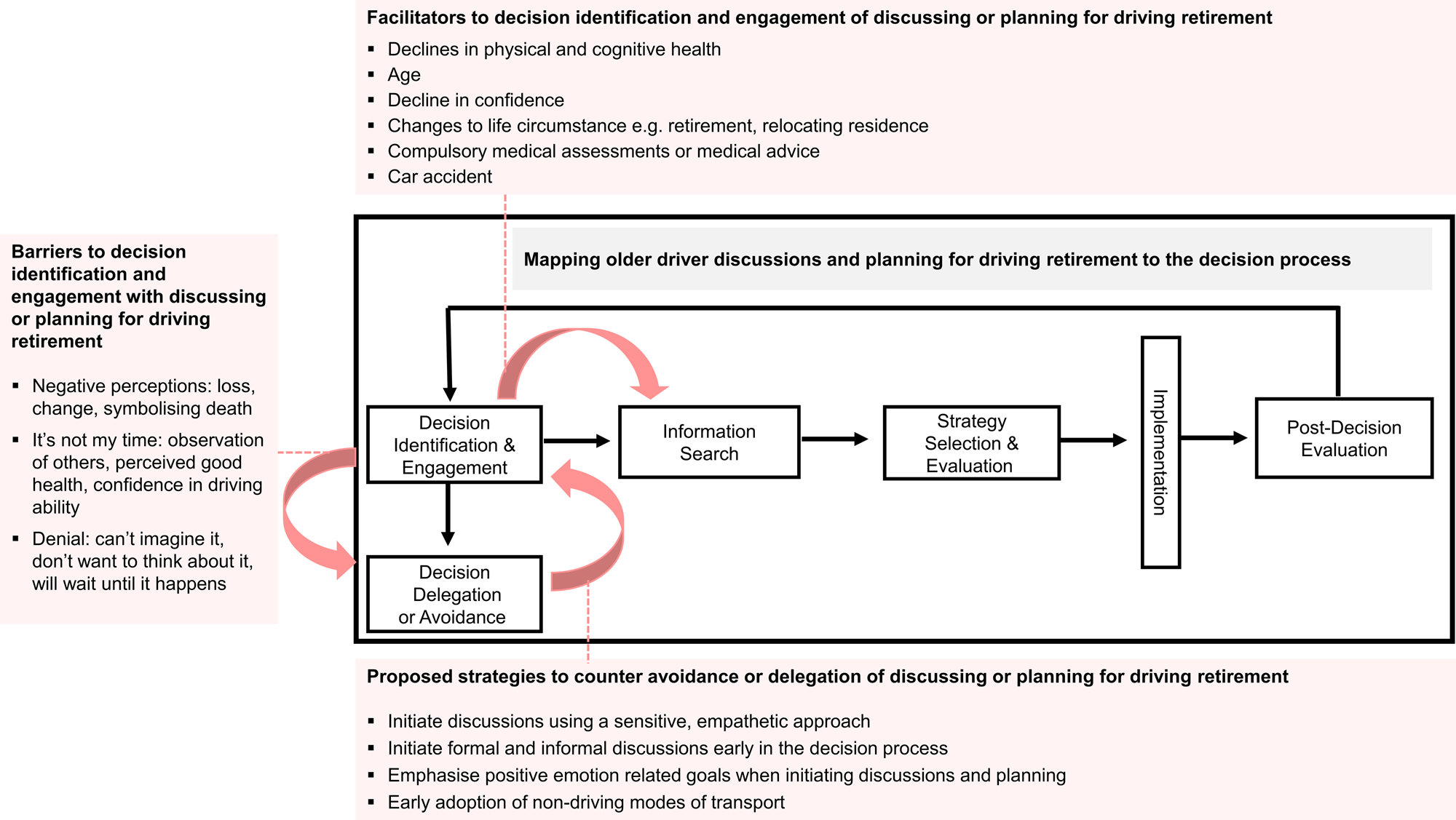

Contributing both theoretically and empirically, the present study used Löckenhoff's framework of decision making for older people to further develop our understanding of decision-making processes in the context of discussions and planning for driving retirement (Löckenhoff, Reference Löckenhoff2018). The facilitators and barriers to discussions and planning for driving retirement are mapped to the decision process (see Figure 2) proposed by Löckenhoff's conceptual framework for mapping age differences in decision making (Löckenhoff, Reference Löckenhoff2018). We discuss in relation to the finding's specific elements of the framework, including task characteristics; age-related mechanisms; and the key stages of the decision process, including decision identification and engagement, decision delegation and avoidance (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Mapping older driver discussions and planning for driving retirement to the ‘Conceptual framework for mapping age differences in decision making’.

Source: Adapted from Löckenhoff (Reference Löckenhoff2018: 141). Copyright © 2017 Karger Publishers, Basel, Switzerland.

Our findings indicate that older drivers perceive driving as a personal and emotional relevant ‘task’ fulfilling an integral and meaningful role in their daily lives (see left middle white box in Figure 1). For many older people in this study, driving embodies more than a convenient mode of transport to undertake practical daily activities. Driving was perceived as crucial to sustaining a sense of independence, spontaneity and freedom. Similarly, alternative models exploring mobility and older people identify these perceived benefits as meeting their practical needs, affective needs (e.g. independence and control) and aesthetic needs (e.g. pleasure) (Musselwhite and Haddad, Reference Musselwhite and Haddad2018). Our findings suggest age-related affective and motivational factors (see Figure 1) are entwined with decisions to avoid discussing or planning for driving retirement. The negative emotions experienced and/or anticipated by older drivers were barriers to engaging in discussions and planning, and therefore decisions about future driving retirement (see Figure 2).

Potential facilitators to discussions and planning for driving retirement are events such as retirement, a driving medical assessment, health declines or a car accident, which may provide critical time-points to which older drivers are more amenable to discussions and planning for driving retirement. Further research is required to understand if these critical time-points: (a) engage older drivers in the decision-making process about driving retirement and (b) facilitate pre-decision information search about alternatives to driving.

Barriers to discussions and planning for driving retirement

Previous studies highlight driving retirement to be a major life event for older people, leading to increased risk of depression and perceptions of feeling older (Chihuri et al., Reference Chihuri, Mielenz, DiMaggio, Betz, DiGuiseppi, Jones and Li2016; Pachana et al., Reference Pachana, Jetten, Gustafsson and Liddle2017). Our study provides further insight proposing older people perceive future negative consequences of loss and change upon driving retirement and view life without driving as a symbol of death. These findings support Löckenhoff's (Reference Löckenhoff2018) framework, which posits affective mechanisms (see top white box in Figure 1) contribute to how older people make decisions. Given older people maintain their capacity to accurately predict future emotions (Löckenhoff, Reference Löckenhoff2018), these negative perceptions anticipated upon driving retirement are valid concerns. Previous studies identify reduced life satisfaction and social participation are indeed experienced by older adults once they stop driving (Liddle et al., Reference Liddle, Gustafsson, Bartlett and Mckenna2012; Pristavec, Reference Pristavec2018). Grief and loss are also emotions experienced by older people living with dementia once they retired from driving (Sanford et al., Reference Sanford, Naglie, Cameron and Rapoport2020). Age-related affective responses, in particular the anticipation of momentous loss, change and death, we propose, are reasons older drivers avoid, defer or delay discussions and planning for driving retirement.

In this study older drivers preferred avoiding, deferring the decision about the timing of driving retirement to a medical practitioner or delaying discussions until a ‘red flag’ incident occurs, such as a car accident or health event. This finding supports other studies which have found that older people rarely discuss or plan for driving retirement (e.g. King et al., Reference King, Meuser, Berg-Weger, Chibnall, Harmon and Yakimo2011; Betz et al., Reference Betz, Villavicencio, Kandasamy, Kelley-Baker, Kim, DiGuiseppi, Mielenz, Eby, Molnar, Hill, Strogatz, Carr and Li2019). The preference of some older drivers to delegate decisions about driving retirement to medical practitioners are conceivably due to such practitioners being considered trusted confidants and experts when it comes to decisions about driving (Betz et al., Reference Betz, Scott, Jones and Diguiseppi2016). Although we found that delegating decision making was preferred by some older drivers, prior studies, in contrast, have found that due to the importance placed on driving, older drivers preferred to be involved in any decisions about their own driving retirement (Betz et al., Reference Betz, Scott, Jones and Diguiseppi2016).

Deferment or avoidance of discussions and planning for driving retirement also support the ageing and decision-making literature, which posits older people prefer to avoid, defer or delegate decisions compared to their younger cohorts (Pethtel and Chen, Reference Pethtel and Chen2013; Löckenhoff, Reference Löckenhoff2018). Motivational mechanisms (see top white box in Figure 1), such as proposed by socioemotional selectivity theory, suggest older people avoid choices that lead to immediate negative emotional outcomes due to their time-limiting lifespan perceptions (Löckenhoff and Carstensen, Reference Löckenhoff and Carstensen2004). However, our findings indicate the thought of driving retirement itself can induce perceptions of a time-limited lifespan for older drivers, leading to avoidance of discussions and planning for driving retirement. Time-limited lifespan perceptions by older people and engagement of avoidance strategies have occurred with other important decisions, such as advanced care planning. End-of-life planning was avoided by older people who had limited lifespan perceptions due to fears of impending mortality (Luth, Reference Luth2016). Older people who perceived they would live for a long time were also less likely to plan for end of life (Luth, Reference Luth2016). Our study similarly showed older drivers who perceived driving retirement was not imminent did not consider that discussing or planning for life without driving were warranted.

When there are perceptions of reduced lifespan, older people will typically choose options that provide positive rather than negative emotional outcomes when making decisions (Löckenhoff and Carstensen, Reference Löckenhoff and Carstensen2004). As identified in this study, some older people associate driving retirement with substantial loss, change and even death. Older drivers perceived that loss and change would occur on both practical and emotional levels. For example, loss and change would occur in relation to important practical daily activities such as grocery shopping, leisure activities like golf and the ability to visit family. Loss is also anticipated in terms of independence, freedom and spontaneity. Similarly, studies from Scandinavia and the United Kingdom identified the car as being integral to maintaining these important everyday activities and quality of life (Hjorthol et al., Reference Hjorthol, Levin and Sirén2010; Musselwhite and Haddad, Reference Musselwhite and Haddad2010). These studies describe fulfilment of these activities in terms of Allardt's wellbeing model of having, loving and being (Hjorthol et al., Reference Hjorthol, Levin and Sirén2010) or practical, aesthetic and affective needs (Musselwhite and Haddad, Reference Musselwhite and Haddad2010).

Guided by Löckenhoff's (Reference Löckenhoff2018) framework, we suggest decisions to discuss driving retirement within the context of ageing and decision-making theory is influenced by affective and motivational mechanisms, contextual factors and the importance of the task of driving (see left middle white box in Figure 1). For most older people in this and prior studies, driving is identified as a personal and emotionally salient task that brings a sense of freedom and independence (Ang et al., Reference Ang, Jennifer, Chen and Lee2019a) and is crucial to maintaining quality of life (Oxley and Whelan, Reference Oxley and Whelan2008; Musselwhite and Haddad, Reference Musselwhite and Haddad2010). Older drivers, therefore, as posited in Löckenhoff's (Reference Löckenhoff2018) framework, prefer to continue driving to prevent losses and preserve their positive meaningful social relationships, activities and quality of life which only driving is perceived to provide (Musselwhite and Haddad, Reference Musselwhite and Haddad2010).

Prior studies have identified that older drivers expressed a diverse range of emotions, including anxiety, anger, sadness and powerlessness, when discussing driving retirement (Betz et al., Reference Betz, Scott, Jones and Diguiseppi2016). In the present study, older drivers associated the need to discuss and plan for driving retirement with death or approaching end of life. Because of the strong association with these negative emotions, an empathetic and staged approach to discussions about driving has been recommended (Betz et al., Reference Betz, Scott, Jones and Diguiseppi2016). However, this might not be adequate to address the end-of-life perceptions experienced by some older drivers. Multiple approaches, including utilisation of decision aids such as those developed for drivers with dementia (Carmody et al., Reference Carmody, Potter, Lewis, Bhargava, Traynor and Iverson2014) or education materials for advanced care planning are effective as a starting point for health practitioners to begin discussions (Solis et al., Reference Solis, Mancera and Shen2018) and could be explored in more depth in future studies on driving retirement. Furthermore, positively reframing these discussions to highlight strategies and messages regarding how older people can maintain independence and their lifestyle into the future is a theoretically supported approach (Löckenhoff, Reference Löckenhoff2018), but warrants further investigation.

Facilitators to discussions and planning for driving retirement

Löckenhoff's (Reference Löckenhoff2018) framework proposes older people draw on prior experiences when making decisions, however, few older drivers in this study had prior experiences of a time without driving. Of the few who did, these experiences were short term. The interview itself triggered many participants to think about life without driving for the first time. Both intrinsic and extrinsic factors were suggested by older drivers as possible facilitators to discussing and planning for driving retirement. Factors such as age, medical assessments, health declines or retirement we consider potential facilitators to decision identification and engagement with the early stages of the driving retirement decision process (see Figure 2) (Löckenhoff, Reference Löckenhoff2018).

Similar to previous studies, we found it is not until ‘red flag’ events such as an accident or health decline that meaningful discussions about driving retirement are likely to occur (Betz et al., Reference Betz, Jones, Petroff and Schwartz2013: 1575). Events such as a car accident, medical advice, or declines in cognition, physical health or driving confidence were identified as red flag indicators for future discussions or planning by older drivers in our study. We suggest triggers such as these are too late in the decision pathway to engage in discussions or plan for driving retirement. To avoid the decision being sudden or forced, regular discussions and planning for driving retirement with health practitioners and enagement with support networks are recommended (Baldock et al., Reference Baldock, Thompson, Dutschke, Kloeden, Lindsay and Woolley2016; Pomidor, Reference Pomidor2019), so that older people can emotionally and logistically prepare for life without driving and maintain quality of life post driving retirement (Musselwhite and Shergold, Reference Musselwhite and Shergold2013; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Johnson, Borkoski, Rebok, Gielen, Soderstrom, Molnar, Pitts, Diguiseppi, Hill, Strogatz, Mielenz, Betz, Kelley-Baker, Eby and Li2019). However, convincing older people to engage with their support networks for this purpose can be a challenge. Older retired drivers experience feelings of being a burden and are more likely to wait for someone to offer them support rather than ask for it in the first instance (Murray and Musselwhite, Reference Murray and Musselwhite2019).

Furthermore, encouraging the early adoption of non-driving modes as part of planning and preparation could be one component of a successful transition to driving retirement for older people, as this study found the few who already adopted other ways of getting around felt better prepared. Strategies to support the older driver to incorporate non-driving options in everyday practice may be required as a prior study found nearly three quarters of drivers who planned to cease driving had not made any practical changes to support this transition (Feng and Meuleners, Reference Feng and Meuleners2020).

Implications and recommendations

This research contributes to emerging literature applying aged-based decision theory to research about older drivers. A key contribution of our study is the application of an aged-based conceptual framework (Löckenhoff, Reference Löckenhoff2018) to provide insights regarding how affective and motivational mechanisms influence older driver decisions to discuss or plan for driving retirement. To complete our understanding of how age impacts decisions to discuss or plan for driving retirement, further research and comparisons are required with younger driver cohorts.

This study has implications for practitioners, e.g. doctors and eye-care practitioners, because they provide yearly fitness-to-drive medical assessments for older drivers (75 years and over in NSW, Australia). The barriers to discussions identified in this study have implications for how health practitioners and family members initiate discussions about driving with older people. When initiating discussions, health practitioners and family should be mindful that for older people, driving retirement may be perceived as an end-of-life stage event.

Based on our findings, and the extant literature, we offer three recommendations for discussions about driving and planning for driving retirement: (a) understand that the value and meaning placed on driving by the older person may vary and should be considered in the context of the individual's lifestyle, identity and perceived consequences of driving retirement; (b) use sensitive and empathetic approaches to discussions and planning for driving retirement, as suggested previously (Betz et al., Reference Betz, Scott, Jones and Diguiseppi2016), because driving retirement may be considered an end-of-life event for some older people; and (c) encourage regular informal and formal discussions about driving and planning for driving retirement with older people. This is because avoidance of discussions about driving are typical and planning in advance for a life without driving can help to maintain quality of life post driving retirement (Musselwhite and Shergold, Reference Musselwhite and Shergold2013).

Approaches to discussions about driving decisions which emphasise positive emotion-related goals is theoretically supported in the context of older people when making decisions more generally (Löckenhoff, Reference Löckenhoff2018). However, further research is required to explore if approaches which emphasise positive emotion-related goals support the decision-making process or prepare the older person for life without driving. In addition, encouraging older drivers to utilise support networks when making decisions about driving, such as family and close confidants, may be worthwhile as they are often involved in the choices older people make (Löckenhoff, Reference Löckenhoff2018). Acknowledging there are barriers and individual differences in how support is utilised and perceived by older retired drivers (Murray and Musselwhite, Reference Murray and Musselwhite2019), maintaining strong support networks to assist with the sensitive discussions, planning and provide emotional and practical support, may help to reduce the negative effects associated with driving retirement (Musselwhite and Shergold, Reference Musselwhite and Shergold2013; Jones et al., Reference Jones, Johnson, Borkoski, Rebok, Gielen, Soderstrom, Molnar, Pitts, Diguiseppi, Hill, Strogatz, Mielenz, Betz, Kelley-Baker, Eby and Li2019). Future research is required to better understand the perspectives of family members in discussions about driving and planning for driving retirement with older people.

Health declines, medical advice and medical driving assessments were identified as facilitators to discussions and planning for driving retirement. Given the barriers faced by medical practitioners to discuss driving with older people (Betz et al., Reference Betz, Jones and Carr2015), it is likely, irrespective of results following the clinical encounter, there is an absence of in-depth discussions about alternatives to driving. A formal approach and provision of supportive resources to encourage discussions at distinct phases is proposed. Further research is required to determine if regular formal, in-depth and meaningful discussions and planning for life post driving retirement is effective in sustaining quality of life and sense of independence and freedom for older people. The findings from this study will inform the development of a decisional support resource for older drivers.

Strengths and limitations

The large number of interviews and diversity in demographic profile including gender, age range and geographical location were a strength of this study. Ideally, a larger sample of older drivers living in rural and remote areas would have been preferred as these demographics have additional challenges in transitioning to life without driving (Hansen et al., Reference Hansen, Newbold, Scott, Vrkljan and Grenier2020). It is possible that the findings from this study may not be generalisable to older people living in more isolated and remote areas, e.g. rural areas with limited public transport options compared to metropolitan areas. They may also lack generalisability to older people from other cultures who may view the role of individual car transport differently to other older people in society and have different levels of social support which may increase or decrease barriers to driving retirement. Furthermore, quantitative studies examining gender and age differences in discussing and planning for driving retirement would be a valuable addition to the research agenda on driving retirement for older people. The findings from this qualitative study did not include regions or cultural groups that are not car dependent. Future studies could include this cohort in the sample in order to compare the decision-making processes of older people who are more and less car dependent.

Conclusion

Driving retirement is a significant life event for many older drivers. Perceptions of loss, change and death are anticipated upon driving retirement. Consequently, it is important older drivers emotionally and practically prepare for life without driving. As older drivers typically avoid or delay discussions and planning for driving retirement, opportunities to initiate discussions early in the decision pathway are warranted. Health practitioners are in a unique position to start the sensitive discussions, address concerns and support the older driver for this life transition. When initiating discussions, an understanding of the value and meaning placed on driving in the context of the older person's identity and lifestyle is necessary.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the contributions to the study design and data collection of Professor Gordon Waitt, Dr Theresa Harada and third-year human geography students, and the support of the Driving in the Senior Years research team at the University of Wollongong.

Financial support

This work was supported by the University of Wollongong (Global Challenges grant scheme).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

Ethical approval to conduct the present study was obtained from the University of Wollongong (2019/ETHO3735).