Introduction

With an ageing society, the demand for health and social care is increasing (Hajek et al., Reference Hajek, Bock, Saum, Matschinger, Brenner, Holleczek, Haefeli, Heider and König2018). Across all Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, ageing has led to health-care expenditure exceeding Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth and without reforms it will increase from 6 per cent in 2010 to 14 per cent of GDP in 2060 (De la Maisonneuve and Oliveira Martins, Reference De la Maisonneuve and Oliveira Martins2013). Whilst inevitably demand for services is set to increase, capacity to respond with formal services is limited (Ashby and Beech, Reference Ashby and Beech2016; Hay et al., Reference Hay, Mercer, Lichtwark, Tran, Hodgson, Aretz, Armstrong and Gorman2017), through a workforce that is itself both ageing and shrinking (World Health Organization, 2005). Traditionally, health and social services focus on acute and episodic care delivered late in the trajectory of an older person's declining health (Bähler et al., Reference Bähler, Huber, Brüngger and Reich2015; Picco et al., Reference Picco, Achilla, Abdin, Chong, Vaingankar, McCrone, Choon Chua, Heng, Magadi, Ling Ng, Prince and Subramaniam2016). There is little attention placed on disease prevention or early identification of loss of independence (Bähler et al., Reference Bähler, Huber, Brüngger and Reich2015; Picco et al., Reference Picco, Achilla, Abdin, Chong, Vaingankar, McCrone, Choon Chua, Heng, Magadi, Ling Ng, Prince and Subramaniam2016). A valuable approach in preventing functional decline is promoting an older person's active participation in daily activities, ranging from activities of daily living (ADL; e.g. bathing, dressing) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL; e.g. cleaning, cooking) through to preferred social, leisure and physical activities at the place of residence or in the local community (Aspinal et al., Reference Aspinal, Glasby, Rostgaard, Tuntland and Westendorp2016). However, health and social care staff often look at older people primarily in terms of frailty and provide care for their clients rather than with them (Whitehead et al., Reference Whitehead, Worthington, Parry, Walker and Drummond2015; Aspinal et al., Reference Aspinal, Glasby, Rostgaard, Tuntland and Westendorp2016). Thereby, despite their best intentions, they may deprive older people of opportunities to engage in daily activities, which may result in further deconditioning and functional decline (Resnick et al., Reference Resnick, Boltz, Galik and Pretzer-Aboff2012; V&VN, 2012; Whitehead et al., Reference Whitehead, Worthington, Parry, Walker and Drummond2015). To stop this downwards spiral, health and social care staff are encouraged to focus on abilities and resources of older people to overcome losses, adapt and maintain independence (Aspinal et al., Reference Aspinal, Glasby, Rostgaard, Tuntland and Westendorp2016).

Over the last two decades, reablement has been implemented and evaluated in many OECD countries. Reablement is often described as an enabling approach that aims to support older people to maximise their competencies to manage their everyday life as independently as possible (Aspinal et al., Reference Aspinal, Glasby, Rostgaard, Tuntland and Westendorp2016). Reablement is similar to the approach of function-focused care or restorative care. While function-focused care has its origin in institutionalised long-term care in the United States of America (USA), the concept of reablement has been developed and delivered mainly in home care across the United Kingdom (UK), Australia, New Zealand and the Scandinavian countries. Common in these approaches is that an attitude of ‘doing with…’ rather than ‘doing for…’ is promoted among health and social care professionals. Restorative care is used as a synonym for both approaches (Metzelthin et al., Reference Metzelthin, Zijlstra, de Man-van Ginkel, van Rossum, Resnick, Lewin, Parsons and Kempen2017). While several countries have already integrated reablement into their national health-care policy, such as Denmark (Rostgaard, Reference Rostgaard2016), New Zealand (Parsons et al., Reference Parsons, Rouse, Sajtos, Harrison, Parsons and Gestro2018), Australia (Commonwealth of Australia, 2015) and the UK (Beresford et al., Reference Beresford, Mann, Parker, Kanaan, Faria, Rabiee, Weatherly, Clarke, Mayhew, Duarte, Laver-Fawcett and Aspinal2019), other countries such as the Netherlands (Metzelthin et al., Reference Metzelthin, Rooijackers, Zijlstra, van Rossum, Veenstra, Koster, Evers, van Breukelen and Kempen2018) or Norway (Tuntland et al., Reference Tuntland, Aaslund, Espehaug, Førland and Kjeken2015; Langeland et al., Reference Langeland, Tuntland, Folkestad, Førland, Jacobsen and Kjeken2019) are still in the phase of conducting research to determine its feasibility, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness. Despite an increasing interest in reablement, there is great variation between and even within countries regarding its conceptual understanding (Aspinal et al., Reference Aspinal, Glasby, Rostgaard, Tuntland and Westendorp2016; Doh et al., Reference Doh, Smith and Gevers2020). For example, what are the characteristics, components, aims and target groups of reablement? Some authors even claim that reablement is an ill-defined concept that lacks a sound theoretical framework, which hinders effective implementation, as there is no agreement regarding the required features to achieve the intended outcomes (Legg et al., Reference Legg, Gladman, Drummond and Davidson2015). In addition, poor conceptual clarity affects the ability to evaluate reablement approaches systematically, and compare and aggregate findings from different studies. This undermines the development of a robust evidence base, resulting in inconsistent and inadequate care delivery, health and social care curricula, and local and national policies.

When comparing a number of recent literature reviews (Ryburn et al., Reference Ryburn, Wells and Foreman2008; Legg et al., Reference Legg, Gladman, Drummond and Davidson2015; Whitehead et al., Reference Whitehead, Worthington, Parry, Walker and Drummond2015; Cochrane et al., Reference Cochrane, Furlong, McGilloway, Molloy, Stevenson and Donnelly2016; Tessier et al., Reference Tessier, Beaulieu, Mcginn and Latulippe2016; Sims-Gould et al., Reference Sims-Gould, Tong, Wallis-Mayer and Ashe2017) and position papers (Aspinal et al., Reference Aspinal, Glasby, Rostgaard, Tuntland and Westendorp2016; Doh et al., Reference Doh, Smith and Gevers2020), there is agreement about several features of reablement. For example, reablement is described as a person-centred and multi-disciplinary approach (Ryburn et al., Reference Ryburn, Wells and Foreman2008; Legg et al., Reference Legg, Gladman, Drummond and Davidson2015; Whitehead et al., Reference Whitehead, Worthington, Parry, Walker and Drummond2015; Aspinal et al., Reference Aspinal, Glasby, Rostgaard, Tuntland and Westendorp2016; Cochrane et al., Reference Cochrane, Furlong, McGilloway, Molloy, Stevenson and Donnelly2016; Tessier et al., Reference Tessier, Beaulieu, Mcginn and Latulippe2016; Sims-Gould et al., Reference Sims-Gould, Tong, Wallis-Mayer and Ashe2017; Doh et al., Reference Doh, Smith and Gevers2020). In addition, there is agreement across studies that reablement approaches have to include components like goal setting and training of daily activities (Ryburn et al., Reference Ryburn, Wells and Foreman2008; Legg et al., Reference Legg, Gladman, Drummond and Davidson2015; Whitehead et al., Reference Whitehead, Worthington, Parry, Walker and Drummond2015; Aspinal et al., Reference Aspinal, Glasby, Rostgaard, Tuntland and Westendorp2016; Cochrane et al., Reference Cochrane, Furlong, McGilloway, Molloy, Stevenson and Donnelly2016; Tessier et al., Reference Tessier, Beaulieu, Mcginn and Latulippe2016; Sims-Gould et al., Reference Sims-Gould, Tong, Wallis-Mayer and Ashe2017; Doh et al., Reference Doh, Smith and Gevers2020). However, other components are less often described, such as regular assessments (Ryburn et al., Reference Ryburn, Wells and Foreman2008; Legg et al., Reference Legg, Gladman, Drummond and Davidson2015; Tessier et al., Reference Tessier, Beaulieu, Mcginn and Latulippe2016) or education and advice (Whitehead et al., Reference Whitehead, Worthington, Parry, Walker and Drummond2015; Cochrane et al., Reference Cochrane, Furlong, McGilloway, Molloy, Stevenson and Donnelly2016; Sims-Gould et al., Reference Sims-Gould, Tong, Wallis-Mayer and Ashe2017). Furthermore, it is unclear whether reablement is limited to promoting active participation in ADL/IADL activities or if increasing and maintaining independence in other activities also belongs to the aims of reablement. To our knowledge, only three papers explicitly mention that reablement can also focus on social, leisure or physical activities (Legg et al., Reference Legg, Gladman, Drummond and Davidson2015; Aspinal et al., Reference Aspinal, Glasby, Rostgaard, Tuntland and Westendorp2016; Doh et al., Reference Doh, Smith and Gevers2020). In addition, there is much discussion about the intensity and duration of reablement approaches. Some authors describe reablement as intense (Ryburn et al., Reference Ryburn, Wells and Foreman2008; Aspinal et al., Reference Aspinal, Glasby, Rostgaard, Tuntland and Westendorp2016; Cochrane et al., Reference Cochrane, Furlong, McGilloway, Molloy, Stevenson and Donnelly2016) and time-limited (Ryburn et al., Reference Ryburn, Wells and Foreman2008; Legg et al., Reference Legg, Gladman, Drummond and Davidson2015; Aspinal et al., Reference Aspinal, Glasby, Rostgaard, Tuntland and Westendorp2016; Cochrane et al., Reference Cochrane, Furlong, McGilloway, Molloy, Stevenson and Donnelly2016; Tessier et al., Reference Tessier, Beaulieu, Mcginn and Latulippe2016; Sims-Gould et al., Reference Sims-Gould, Tong, Wallis-Mayer and Ashe2017; Doh et al., Reference Doh, Smith and Gevers2020), while others (Whitehead et al., Reference Whitehead, Worthington, Parry, Walker and Drummond2015) report that reablement does not necessarily have to end after a few weeks. Last but not least, there is discussion about the target group of reablement. While some authors (Aspinal et al., Reference Aspinal, Glasby, Rostgaard, Tuntland and Westendorp2016; Tessier et al., Reference Tessier, Beaulieu, Mcginn and Latulippe2016) describe reablement as an inclusive approach, Ryburn et al. (Reference Ryburn, Wells and Foreman2008) report that reablement is primarily aimed at older people at the beginning of their home care journey, often after hospital admission. In addition, people with chronic illnesses, terminal diseases or dementia are, according to Cochrane et al. (Reference Cochrane, Furlong, McGilloway, Molloy, Stevenson and Donnelly2016), predominantly excluded from reablement approaches as, in their view, these people have no potential to benefit from them.

In 2018, the ReAble network (https://reable.auckland.ac.nz/) was established with 28 members from Denmark, Sweden, Norway, the Netherlands, UK, USA, Canada, Australia and New Zealand. Individual and country membership was broadly based on prior experience in implementing or evaluating reablement approaches. It was of utmost importance to the network to develop an internationally agreed definition of reablement, as this is seen as a first step towards a sound evidence base. Consequently, a Delphi study was conducted with the aim of reaching agreement on the characteristics, components, aims and target groups of reablement, leading towards an internationally accepted definition of this approach.

Methods

Design

A Delphi study was conducted between September 2018 and March 2019. The Delphi technique is a widely used method to reach consensus among experts by making use of several rounds of opinion collection and feedback (Hasson et al., Reference Hasson, Keeney and McKenna2000). Our Delphi study consisted of four Web-based Delphi survey rounds using an online survey program (QualtricsXM). Before the start of the Delphi study, a literature search was conducted with the aim of identifying scientific papers that describe features (i.e. characteristics, components, aims and target groups) of reablement. The results of the literature study were used as a starting point when designing the first Delphi survey.

Participants

Academics as well as practitioners were eligible to participate in the Delphi study, as long as they had considerable experience with reablement approaches. Participants were identified by the literature review and word of mouth. With regard to the academics, eligible participants had to be (a) first author of at least one English peer-reviewed reablement publication; or (b) member of the ReAble network; or (c) identified by the members of the ReAble network as experts in the field of reablement. Practitioners were identified by the participating academics. There were no specific eligibility criteria for this group. In total, 112 experts in the field of reablement (i.e. academics and practitioners) from 11 different countries were invited to participate. Excluded from participation were the authors of the present paper. All identified reablement experts (N = 112) were invited by email to participate in the Delphi study, which included a link to the first survey.

Data collection and analysis

The Web-based survey process consisted of four rounds, each round taking approximately one month to administer. This included: (a) delivery of the survey, including reminders to the participants within two weeks; (b) analysis of the results; and (c) compilation of a new survey including the comments that were collected in the previous Delphi round. All analyses were conducted using SPSS version 25 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Delphi round 1: September 2018 to October 2018

In the first survey round, background characteristics of experts (i.e. age, sex, years of experiences with reablement approaches) were collected. In addition, experts were asked to rate the relevance of characteristics (e.g. person-centred, time-limited, inter-disciplinary), components (e.g. goal-oriented treatment plan, training of daily activities), aims (e.g. increase clients’ independence) and target groups (e.g. age, setting) of reablement that were identified in scientific papers. In total, six characteristics, 11 components, seven aims and six target groups were rated regarding their relevance for a definition of reablement using a nine-point Likert scale, with higher scores indicating higher importance (see the example in Figure 1).

Figure 1. Example of survey questions.

In line with previous research, items were identified as important for a definition of reablement, when they had a median of 7–9 and an interquartile range (IQR) of ≤2 (Elissen et al., Reference Elissen, Metzelthin, van den Bulck, Verbeek and Ruwaard2017). Items with a median of 1–3 and an IQR ≤2 were considered as less important and excluded. The remaining items were considered uncertain. These items were rated again in the next round.

Delphi round 2: October 2018 to November 2018

Uncertain items were rated by experts using a binary answer option (include in definition versus do not include in definition). At least two-thirds of the participants had to rate ‘include’ to consider the item as relevant to include in the definition of reablement. The results of the first and second survey were used to formulate three preliminary definitions of reablement.

Delphi round 3: December 2018 to January 2019

The three preliminary definitions of reablement were ranked by experts from 1 (being most preferred) to 3 (being less preferred) to identify the definition that reached the most agreement among experts. In addition, final comments regarding the definition were gathered from the experts to fine-tune the preferred definition.

Delphi round 4: February 2019 to March 2019

In the last survey round, the preferred and fine-tuned definition was shared with the experts. They were asked whether they agreed or did not agree with the definition. There is no hard cut-off for the level of agreement in Delphi studies (Jorm, Reference Jorm2015), but other researchers have argued previously that 70 per cent is an adequate level of agreement (Hsu and Sandford, Reference Hsu and Sandford2007; Feo et al., Reference Feo, Conroy, Jangland, Muntlin Athlin, Brovall, Parr, Blomberg and Kitson2018). Therefore, we stated that the final definition had to be accepted by at least 70 per cent of the experts. Each expert who did not support the definition of reablement was given an opportunity to explain their decision.

Results

In total, 82 experts participated in the Delphi study, which corresponds with a response rate of 73 per cent. The experts were from 11 countries: Australia (N = 9), Canada (N = 2), Denmark (N = 13), Ireland (N = 3), Netherlands (N = 5), New Zealand (N = 8), Norway (N = 17), Sweden (N = 9), Taiwan (N = 1), UK (N = 8) and USA (N = 7). In total, 77 per cent of experts were working in academia and the remaining 23 per cent were practitioners (i.e. executive/directors (21%), managers/head of area (74%) or nurses (5%)). Experts had on average 8.0 (standard deviation (SD) = 5.6) years of experience in conducting research about reablement and 12.0 (SD = 7.2) years of experience in delivering reablement approaches. For the study flow, see Figure 2.

Figure 2. Delphi study flowchart.

Delphi round 1

In the first round, 82 out of 112 experts (73%) completed the survey. There was consensus among experts about the relevance of two characteristics (i.e. person-centred, holistic), seven components (i.e. assessment, goal-oriented treatment plan, regular reassessment of treatment plan, training of daily activities, use of home modifications and assistive devices, involvement of social network, reablement training and support for staff), four aims (i.e. increasing clients’ independency in daily activities, enabling clients to participate in meaningful activities, enabling clients to be engaged in the community, reducing need for long-term care needs and related costs) and three target groups (i.e. irrespective of diagnosis, age, physical capacity). In addition, a number of uncertain features were identified. More specifically, four characteristics, four components, three aims and three target groups had to be rated again in Delphi round 2. No irrelevant items were identified.

Delphi round 2

In the second round, 79 of the 82 participating experts (96%) completed the survey. In addition to the relevant items identified in Delphi round 1, there was consensus among experts about the relevance of a further three characteristics (i.e. intensive, multi-disciplinary, co-ordinated), one aim (i.e. enhancing clients’ physical functioning) and two target groups (i.e. irrespective of setting and type of problem). An overview of all identified characteristics, components, aims and target groups per round is provided in Table 1.

Table 1. Overview of reablement characteristics, components, aims and target groups

Notes: IQR: interquartile range. ✓: consensus among experts about relevance. ?: uncertain features, rated again in the next round. –: irrelevant items according to experts.

Delphi round 3

In the third round, 74 of 82 experts (90%) rated three preliminary definitions of reablement. Definition A was preferred by most experts (45%):

Reablement is a person-centred and holistic approach that aims to increase or maintain clients’ independence and participation in daily and meaningful activities (at home or in the community) and to reduce their need for long-term services and related costs. Reablement consists of multiple visits and is delivered by a trained multidisciplinary team, coordinated and supported by a health professional, such as a registered nurse, social worker or allied health professional. Reablement services have shared components that include a comprehensive assessment, a goal-oriented treatment plan and regular reviews of the treatment plan. Clients’ goals can be reached through training of daily activities, by making use of home modifications and assistive devices and by involving the social network of the client. Reablement is an inclusive approach irrespective of age, physical capacity, diagnosis or setting.

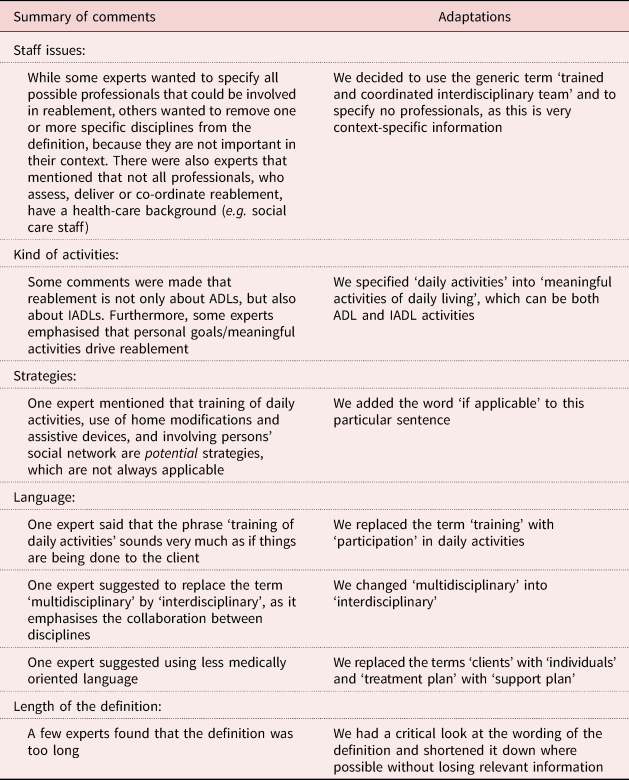

Definitions C and B were preferred by 28 and 27 per cent, respectively. In addition, comments were collected to fine-tune the final definition. Comments were related to staff issues, kind of activities, strategies, language and length of the definition. Table 2 provides more details and shows how these comments were taken into account when adapting the definition.

Table 2. Comments from Delphi round 3

Notes: ADL: activity of daily living. IADL: activity of daily living.

There were also some comments which we could not take into account without harming the results of the previous two Delphi rounds. First, no consensus was reached that reablement (a) has to include a physical exercise component; (b) is time-limited; and (c) aims to motivate clients. Therefore, these features were not included in the definition. Second, in the previous two Delphi rounds, no consensus was reached that reablement approaches are applicable for clients irrespective of their mental capacity. However, there was consensus that it is appropriate for clients with all kinds of diagnoses. Therefore, clients with for example Alzheimer's disease or depression do not necessarily have to be excluded from reablement approaches. Third, in the previous two Delphi rounds, there was consensus that ‘reducing long-term services’ is an aim of reablement. Consequently, this aim cannot be deleted in the definition as suggested by one expert.

Delphi round 4

After viewing Delphi round 3, one expert asked to be withdrawn from the study. Therefore, in the last survey round, 79 of 81 experts (98%) participated. Of the 79 experts that completed the survey, 62 experts from across 11 countries agreed with the definition (79%). Experts from five countries had 100 per cent agreement on the definition (i.e. Canada, Ireland, New Zealand, Taiwan and the USA). Denmark and the Netherlands had only one expert each that did not support the definition, which corresponds with an agreement rate of 92 and 80 per cent, respectively, within that country. Also two-thirds of the Australian, Swedish and Norwegian experts agreed with the definition (67, 67 and 64%, respectively). Only the UK had fewer than half of their experts agreeing with the definition (42%). Out of the 17 experts who were not agreeing with the definition, 11 experts (65%) perceived that there was too much emphasis on ‘physical’ functioning. Next to ‘enhancing clients’ physical functioning’, agreement was reached on increasing clients’ independency in daily activities, enabling clients to participate in meaningful activities and enabling clients to be engaged in the community. This shows a strong focus on daily, meaningful and social activities. Enabling clients to undertake these activities may ask for restoring various functions (e.g. physical, cognitive and social), but in the Delphi study agreement was only reached about physical functioning. To emphasise that restoring functionality and independence is not necessarily limited to enhancing physical functioning, the research team replaced the term ‘physical functioning’ by ‘physical and/or other functioning’. Other reasons experts stated for not agreeing with the definition were that reablement was not delivered by an inter-disciplinary team in their context (mentioned by three experts; 18%) or that there was too little emphasis on the meaningfulness of activities (mentioned by three experts; 18%). Other reasons were only mentioned by a single expert, e.g. not including time-limited as a characteristic or that reablement approaches can be delivered to individuals irrespective of the setting. We did not adapt the definition with regard to these comments, as they were only argued once. The final definition of reablement is shown below:

Reablement is a person-centred, holistic approach that aims to enhance an individual's physical and/or other functioning, to increase or maintain their independence in meaningful activities of daily living at their place of residence and to reduce their need for long-term services. Reablement consists of multiple visits and is delivered by a trained and coordinated interdisciplinary team. The approach includes an initial comprehensive assessment followed by regular reassessments and the development of goal-oriented support plans. Reablement supports an individual to achieve their goals, if applicable, through participation in daily activities, home modifications and assistive devices as well as involvement of their social network. Reablement is an inclusive approach irrespective of age, capacity, diagnosis or setting.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to reach agreement on the characteristics, components, aims and target groups of reablement leading to an international definition of reablement. The final definition, which was accepted by 79 per cent of the participating experts, contains a broad range of components. Some of these components (e.g. goalsetting; Ryburn et al., Reference Ryburn, Wells and Foreman2008; Legg et al., Reference Legg, Gladman, Drummond and Davidson2015; Whitehead et al., Reference Whitehead, Worthington, Parry, Walker and Drummond2015; Aspinal et al., Reference Aspinal, Glasby, Rostgaard, Tuntland and Westendorp2016; Cochrane et al., Reference Cochrane, Furlong, McGilloway, Molloy, Stevenson and Donnelly2016; Tessier et al., Reference Tessier, Beaulieu, Mcginn and Latulippe2016; Sims-Gould et al., Reference Sims-Gould, Tong, Wallis-Mayer and Ashe2017; Doh et al., Reference Doh, Smith and Gevers2020) are in line with previous literature reviews (Ryburn et al., Reference Ryburn, Wells and Foreman2008; Legg et al., Reference Legg, Gladman, Drummond and Davidson2015; Whitehead et al., Reference Whitehead, Worthington, Parry, Walker and Drummond2015; Cochrane et al., Reference Cochrane, Furlong, McGilloway, Molloy, Stevenson and Donnelly2016; Tessier et al., Reference Tessier, Beaulieu, Mcginn and Latulippe2016; Sims-Gould et al., Reference Sims-Gould, Tong, Wallis-Mayer and Ashe2017) and position papers (Aspinal et al., Reference Aspinal, Glasby, Rostgaard, Tuntland and Westendorp2016; Doh et al., Reference Doh, Smith and Gevers2020), while other components were added (e.g. regular assessments; Ryburn et al., Reference Ryburn, Wells and Foreman2008; Legg et al., Reference Legg, Gladman, Drummond and Davidson2015; Tessier et al., Reference Tessier, Beaulieu, Mcginn and Latulippe2016). Furthermore, agreement was reached among participating experts that reablement approaches aim to increase or maintain independence in a broad range of daily activities, including social, leisure or physical activities, which were described only in a few literature reviews and position papers (Legg et al., Reference Legg, Gladman, Drummond and Davidson2015; Aspinal et al., Reference Aspinal, Glasby, Rostgaard, Tuntland and Westendorp2016; Doh et al., Reference Doh, Smith and Gevers2020) previously. What exactly is meant by independence may vary among clients. For some, it may mean being able to manage all activities without assistance, for others it could mean maintaining independence in some activities of daily living (e.g. washing face and brushing teeth) while needing support with other activities (e.g. going for a walk). Therefore, it is very important that reablement takes into account clients’ goals.

Participating experts agreed that reablement is an inclusive approach, irrespective of age, capacity, diagnosis or setting. This finding is in contrast with the review of Ryburn et al. (Reference Ryburn, Wells and Foreman2008), who reported that reablement approaches are primarily aimed at older people at the beginning of their home care journey, often after hospital admission. Also Cochrane et al. (Reference Cochrane, Furlong, McGilloway, Molloy, Stevenson and Donnelly2016) argued in their systematic review that people with chronic illnesses, terminal diseases or dementia are not considered for reablement, as they have no potential to benefit from it. However, two recent studies from Australia (Poulos et al., Reference Poulos, Bayer, Beaupre, Clare, Poulos, Wang, Zuidema and McGilton2017; Jeon et al., Reference Jeon, Clemson, Naismith, Mowszowski, McDonagh, Mackenzie, Dawes, Krein and Szanton2018) showed that reablement approaches can also be promising for people with dementia. According to Poulos et al. (Reference Poulos, Bayer, Beaupre, Clare, Poulos, Wang, Zuidema and McGilton2017), people with dementia still have the capacity to increase or maintain their functional ability, which can positively influence their health and wellbeing. This finding is in line with the case study described by Jeon et al. (Reference Jeon, Clemson, Naismith, Mowszowski, McDonagh, Mackenzie, Dawes, Krein and Szanton2018), in which reablement resulted in increased confidence and physical strength, more participation in daily activities and improved wellbeing. However, the authors acknowledged that additional reablement strategies have to be taken into account to compensate for affected attention, memory, orientation, and executive function such as cognitive rehabilitation, assistive devices and a strong involvement of the informal care-giver (Poulos et al., Reference Poulos, Bayer, Beaupre, Clare, Poulos, Wang, Zuidema and McGilton2017; Jeon et al., Reference Jeon, Clemson, Naismith, Mowszowski, McDonagh, Mackenzie, Dawes, Krein and Szanton2018, Reference Jeon, Simpson, Low, Woods, Norman, Mowszowski, Clemson, Naismith, Brodaty, Hilmer, Amberber, Gitlin and Szanton2019).

In the present Delphi study, participating experts agreed that reablement approaches do not have to be time-limited, which is in conflict with most previous literature reviews and discussion papers. While some authors described reablement as a time-limited approach (Ryburn et al., Reference Ryburn, Wells and Foreman2008; Legg et al., Reference Legg, Gladman, Drummond and Davidson2015; Aspinal et al., Reference Aspinal, Glasby, Rostgaard, Tuntland and Westendorp2016; Cochrane et al., Reference Cochrane, Furlong, McGilloway, Molloy, Stevenson and Donnelly2016; Tessier et al., Reference Tessier, Beaulieu, Mcginn and Latulippe2016; Sims-Gould et al., Reference Sims-Gould, Tong, Wallis-Mayer and Ashe2017; Doh et al., Reference Doh, Smith and Gevers2020), only Whitehead et al. (Reference Whitehead, Worthington, Parry, Walker and Drummond2015) reported that reablement does not necessarily have to end after a few weeks. Also the fact that participating experts agreed that reablement is also a promising approach in institutionalised long-term care is not in line with previous literature reviews (Ryburn et al., Reference Ryburn, Wells and Foreman2008; Legg et al., Reference Legg, Gladman, Drummond and Davidson2015; Whitehead et al., Reference Whitehead, Worthington, Parry, Walker and Drummond2015; Cochrane et al., Reference Cochrane, Furlong, McGilloway, Molloy, Stevenson and Donnelly2016; Tessier et al., Reference Tessier, Beaulieu, Mcginn and Latulippe2016; Sims-Gould et al., Reference Sims-Gould, Tong, Wallis-Mayer and Ashe2017) and position papers (Aspinal et al., Reference Aspinal, Glasby, Rostgaard, Tuntland and Westendorp2016; Doh et al., Reference Doh, Smith and Gevers2020). However, there are some recent studies, e.g. the study of Low et al. (Reference Low, Venkatesh, Clemson, Merom, Casey and Brodaty2018), that provided evidence that reablement is also a promising approach with regard to several clients’ outcomes (i.e. depressive symptoms, functioning and social care related to quality of life) in residential care. The added value of reablement in a wide range of care settings is also supported by the work of Resnick et al. (Reference Resnick, Galik and Boltz2013), who conducted several studies in acute (i.e. hospital) and long-term care (i.e. nursing homes, assisted living and home care).

There were some differences in agreement rates across countries, with the lowest agreement rate among experts from the UK (42%). According to a recent National Health Service report (Beresford et al., Reference Beresford, Mann, Parker, Kanaan, Faria, Rabiee, Weatherly, Clarke, Mayhew, Duarte, Laver-Fawcett and Aspinal2019), reablement is described as a ‘time-limited’ approach to make a distinction between reablement and generic rehabilitation services. Rehabilitation is often offered after an acute event whereas reablement more often follows a gradual decline and therefore can be applied in a preventive manner. In addition, rehabilitation is often medically directed and occurs in hospital or ambulatory settings. Reablement takes a more holistic approach and is applied in the place of residence. Ultimately, reablement aims to enable the person to increase or maintain their independence in daily life by promoting an attitude of ‘doing with…’ rather than ‘doing for…’ among health and social care professionals (Metzelthin et al., Reference Metzelthin, Zijlstra, de Man-van Ginkel, van Rossum, Resnick, Lewin, Parsons and Kempen2017). According to the definition, reablement aims to reduce the need for long-term services, which means a reduction or prevention of services as consequence of reablement. Time-limited refers to the level of service input. Reablement is often applied as a time-limited intervention, usually 6–12 weeks. However, in some cases, people might need support for a longer period. Reablement even has the potential to be implemented in traditional long-term care like in the Netherlands or the USA, as long as the ethos of reablement (‘doing with…’) is respected. Next to the disagreement regarding the time-limited nature of reablement, the low agreement rate in the UK is potentially due to the fact that the final definition in the Delphi study states that reablement ‘is delivered by a trained and coordinated interdisciplinary team’. In their report, Beresford et al. (Reference Beresford, Mann, Parker, Kanaan, Faria, Rabiee, Weatherly, Clarke, Mayhew, Duarte, Laver-Fawcett and Aspinal2019) presented four different patterns of staffing and skill mix in the UK: (a) reablement workers only, (b) home care reablement, (c) reablement with occupational therapy, and (d) inter-disciplinary reablement approaches. These patterns are also recognised in other countries. For example, in New Zealand reablement is delivered by support workers and registered nurses with support from the wider inter-disciplinary team (King et al., Reference King, Parsons and Robinson2012a, Reference King, Parsons, Robinson and Joergensen2012b), while in the Dutch ‘Stay Active at Home’ study, reablement is provided by home care teams (i.e. domestic support workers and nurses) (Metzelthin et al., Reference Metzelthin, Zijlstra, de Man-van Ginkel, van Rossum, Resnick, Lewin, Parsons and Kempen2017, Reference Metzelthin, Rooijackers, Zijlstra, van Rossum, Veenstra, Koster, Evers, van Breukelen and Kempen2018). In contrast, in Norway, reablement is strongly influenced by occupational therapists and is delivered by an inter-disciplinary team that also includes other disciplines such as nurses, social educators, physiotherapists, home-helpers and assistants (Langeland et al., Reference Langeland, Tuntland, Førland, Aas, Folkestad, Jacobsen and Kjeken2015, Reference Langeland, Tuntland, Folkestad, Førland, Jacobsen and Kjeken2019; Tuntland et al., Reference Tuntland, Aaslund, Espehaug, Førland and Kjeken2015). It has to be acknowledged that the composition of reablement teams can vary between and even within countries and is not limited to health-care professionals.

This study has several strengths and limitations that need to be discussed. First, in this study a large sample of reablement experts, both academics and practitioners, from 11 countries participated. However, selection bias may have occurred since most experts were identified based on at least one English peer-reviewed reablement publication. In addition, all experts needed sufficient English skills to fill in the surveys. Consequently, practitioners, especially from non-English-speaking countries, might have been underrepresented in the sample. In addition, all members of the ReAble network were invited to participate in the Delphi study. As most network members are from Denmark, Sweden and Norway, the Scandinavian countries were overrepresented in our sample. Reablement is applied in different ways across the world, mostly influenced by contextual circumstances. Consequently, experts may have had different approaches in mind when participating in the Delphi study. A strength of our study is that we incorporated both the state-of-the-art literature and the opinions of experts, which has not been done before. For example, a previous discussion paper was based on literature only (Doh et al., Reference Doh, Smith and Gevers2020). However, it must be acknowledged that we did not conduct a systematic literature review of the reablement literature.

In conclusion, this Delphi study succeeded in developing an internationally accepted definition of reablement, across academia and practice. However, to ensure its widespread use, it is important to translate the definition into various languages, with back translation to ensure validity and to contextualise it to take into account national and local policy and institutional contexts. Although we are aware of the differences between and within countries in how reablement approaches are applied in practice, this study is a first step towards more conceptual clarity when defining reablement. Future research can be conducted regarding the implementation of agreed reablement components. For example, a wide variety of assessment tools are used to evaluate the capabilities of clients. In addition, research is needed in other promising target groups, such as people with chronic illnesses or terminal diseases. More research in this field will facilitate collaborative learning, which potentially leads towards more effective service delivery and better client outcomes. Furthermore, the evidence would be valuable for the development of educational programmes for health and social care staff, and local and national policies.

Acknowledgements

We thank the experts for their participation in this study.

Author contributions

All authors were involved in the conception and design of the study. EB was responsible for the data collection and analysis. All authors were involved in the interpretation of the data. SFM made a first draft of the paper. MP, TR and EB revised it critically for important intellectual content and gave approval for the final version to be published.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Western Australian Department of Health Merit Award. The initiation of the ReAble network has been funded by the Nordic NORDFORSK research funding agency.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

Potential participants were informed by an information sheet about the aim and the design of the study. Completion of the first Delphi survey was taken as evidence of consent. Participation was voluntary and participants could withdraw from the study at any time without providing a reason for withdrawal. There were no risks related to participating in this study. All collected data were de-identified (coded). Only the research team had access to the code. Any collected information was treated confidentially and used only in this project. Ethical approval to conduct this study was granted by the Curtin University Human Research Ethics Committee (reference number 15130-04).