Introduction

For the first time in history, an increase in life expectancy globally has created more older people in the population, and it is predicted to reach 20 per cent of the total population by 2050 (World Health Organization (WHO), 2015; Hunter et al., Reference Hunter, Hadjistavropoulos and Kaasalainen2016). Higher rates of life expectancy, however, are not commensurate to healthy ageing, as older people today are experiencing elevated rates of dementia and other chronic long-term conditions (WHO, 2015). Yet whilst deaths from cardiac disease, stroke, prostate cancer and other long-term conditions decreased between 2000 and 2015, deaths from Alzheimer's increased by 123 per cent (Alzheimer's Association, 2018). Globally, in 2015 more than 47 million people had a diagnosis of dementia and by 2030 it is estimated that 75 million people will be affected by the condition (WHO, 2015).

Currently, in the United Kingdom (UK) there are 850,000 people living with dementia (Alzheimer's Society, 2014) with an estimated cost to the economy of £26 billion a year, a figure predicted to double in the next 30 years (Department of Health, 2015). Two-thirds of people with dementia live in the community and are being looked after by approximately 670,000 informal carers (ICs), saving the state £11 billion per year (Alzheimer's Society, 2015).

Informal or family care-givers are usually a family member, often a spouse or friend, generally female, who assumes the overall caring responsibility for a person experiencing daily difficulties due to a debilitating condition, physical, cognitive or emotional, including dementia (Brodaty and Donkin, Reference Brodaty and Donkin2009; Alzheimer's Society, 2015; Carers Trust, 2015; Bertogg and Strauss, Reference Bertogg and Strauss2018). Informal care-giving will generally have a relational dimension, and whilst often the spouse is the main carer, other family members often provide a significant contribution (McDonnell and Ryan, Reference McDonnell and Ryan2014). There are many stages to caring and indeed the nature and type of care varies depending on the needs of the person receiving the care (São José, Reference São José2018). Many studies have reported the negative impact of care-giving, particularly on those who care for people living with dementia who may experience clinical depression or anxiety or other less-severe psychological impacts (Cross et al., Reference Cross, Garip and Sheffield2018; Ryan et al., Reference Ryan, Laird, McCauley, Gibson, Mulvenna, Curran, Bunting, Ferry and Bond2018; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Liu, Robinson, Shawler and Zhou2018; Watson et al., Reference Watson, Tatangelo and McCabe2018).

Mainly, the care-giving model has been explained using the framework of stress-coping models whereby ‘the onset and progression of chronic illness and physical disability are stressful for both the patient and the caregiver’ (Schulz and Sherwood, Reference Schulz and Sherwood2008: 105–113; see also Doebler et al., Reference Doebler, Ryan, Shortall and Maguire2016). Other factors affecting care-givers are associated with the type of care provided. Archbold (Reference Archbold1983) initially conceptualised care-giving into two types: care providers and care managers, however, this falls short of capturing the complexity of informal care/caring as described by São José (Reference São José2018) who attempts to critique the empirical literature on this topic specifically for the fourth age (later life with care, associated with loss of agency and decay), highlighting the inherent complexity of caring.

Policy guidance and indeed societal preference promotes home-based care for people living with dementia (Department of Health, 2015). Many often ultimately move into care homes when ICs are unable to manage their growing care needs (Livingston et al., Reference Livingston, Sommerlad, Orgeta, Costafreda, Huntley, Ames, Ballard, Banerjee, Burns, Cohen-Mansfield, Cooper, Fox, Gitlin, Howard, Kales, Larson, Ritchie, Rockwood, Sampson, Samus, Schneider, SelbÃõk, Teri and Mukadam2017; Garvelink, Reference Garvelink, Groen-van de Ven, Smits, Franken, Dassen-Vernooij and Légaré2018). However, research has shown that people living with dementia who reside in care homes experience lower quality of life than those living at home (Ryan and McKenna, Reference Ryan and McKenna2015; Robertson et al., Reference Robertson, Cooper, Hoe, Hamilton, Stringer and Livingston2017; Ballard et al., Reference Ballard, Corbett, Orrell, Williams, Moniz-Cook, Romeo, Woods, Garrod, Testad, Woodward-Carlton, Wenborn, Knapp and Fossey2018). In recent years, different models of long-term support have been introduced (Livingston et al., Reference Livingston, Sommerlad, Orgeta, Costafreda, Huntley, Ames, Ballard, Banerjee, Burns, Cohen-Mansfield, Cooper, Fox, Gitlin, Howard, Kales, Larson, Ritchie, Rockwood, Sampson, Samus, Schneider, SelbÃõk, Teri and Mukadam2017). In the UK, the recognition of the link between housing and health has gained traction (Wild et al., Reference Wild, Clelland, Whitelaw, Fraser and Clark2018), and extra-care housing has emerged as an alternative to sheltered housing or very sheltered housing, currently referred to as housing with care; a model known in the United States of America (USA) as assisted living (Brooker et al., Reference Brooker, Argyle, Scally and Clancy2011). Similarly, there has been a growing interest in the development of small-scale, home-like residential care models with facilities specifically designed for people living with dementia such as the Eden Alternative (Livingston et al., Reference Livingston, Sommerlad, Orgeta, Costafreda, Huntley, Ames, Ballard, Banerjee, Burns, Cohen-Mansfield, Cooper, Fox, Gitlin, Howard, Kales, Larson, Ritchie, Rockwood, Sampson, Samus, Schneider, SelbÃõk, Teri and Mukadam2017). These models of care provision aspire to preserve the rights of people living with dementia to choice and control over their housing options with a greater focus on independent living (Department of Health, 2015).

One such type of small-scale, home-like residential care models is called supported housing. Supported housing is defined as ‘any housing scheme where housing is provided alongside care, support or supervision to help people live as independently as possible in the community’ (Department for Communities and Local Government and Department for Work and Pensions, 2016: 9–10). Essentially, housing and care services are separate entities. Care services are provided by staff over a 24-hour period, but nursing services are not available. Housing is rented from a housing association and each tenant must sign a tenancy agreement upon moving into the housing scheme. Typically, tenants rent a self-contained apartment or flat, and a care plan is developed with the support team after an individual needs assessment. Household tasks can be completed by the tenant independently or with support from a family care-giver, staff care-giver or paid for from an alternative source. A range of social activities are available and are often integrated into the wider community. This model can be tailored according to specific need and by this very nature of the model is a person-centred approach. It enables tenants to maintain life skills, independence and have support where necessary.

Supported living strives to become an alternative to a person's own home when it is no longer possible for the individual to live on their own. Transitioning into any care environment is a significant life event (Ryan et al., Reference Ryan, McKenna and Slevin2011). Fostering a sense of home, place and belonging within any care environments is very important (Ryan and McKenna, Reference Ryan and McKenna2015; Van Hoof et al., Reference Van Hoof, Janssen, Heesakkers, Van Kersbergen, Severijns, Willems, Marston, Janssen and Nieboer2016). Research indicates that multiple factors impact on the sense of home such as feeling secure, maintaining identity, independence, choice and nurturing memories (Rijnaard et al., Reference Rijnaard, van Hoof, Janssen, Verbeek, Pocornie, Eijkelenboom, Beerens, Molony and Wouters2016). Additionally, comfort, a sense of ease, as well as the ability to be one's self and establish relationships is important. Interrelating factors such as the social, environmental and psychological context have also been identified but further research is needed to identify how they could enhance individuals’ sense of home (Rijnaard et al., Reference Rijnaard, van Hoof, Janssen, Verbeek, Pocornie, Eijkelenboom, Beerens, Molony and Wouters2016). O'Malley and Croucher (Reference O'Malley and Croucher2005) reported that independence, privacy and security are essential features of extra-care housing.

Many of the supported housing options for people with dementia include technology, both traditional technologies like pull cords and automated reminders and more pervasive systems integrated into the home space, creating the smart home. Amiribesheli et al. (Reference Amiribesheli, Benmansour and Bouchachia2015) highlighted that smart home technologies used inter-related software and hardware to monitor the behaviour within the living space, develop an understanding of activities and identify risks.

Smart home technologies can aim to enrich and inform care support, increasing the person living with dementia's freedom and independence (White and Montgomery, Reference White and Montgomery2014; Daly-Lynn et al., Reference Daly-Lynn, Rondon-Sulbaran, Quinn, Ryan, McCormack and Martin2017); free up the care-giver's time for meaningful interaction and other duties (Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Hutchings, Corner, Finch, Hughes, Brittain and Bond2007); give peace of mind for the care-giver (Alwin et al., Reference Alwin, Persson and Krevers2013; Mao et al., Reference Mao, Chang, Yao, Chen and Huang2015); and reduce unnecessary physical intrusion (Morgan, Reference Morgan2003). The challenges associated with such an environment include technology replacing care as oppose to complementing care provision (Landau, Reference Landau2009), unreliability and failure of devices (Altendorf and Schreiber, Reference Altendorf and Schreiber2015), a noisy living environment due to alarms (Bressler et al., Reference Bressler, Redfern and Brown2011) and a violation of privacy (Niemeijer et al., Reference Niemeijer, Frederiks, Riphagen, Legemaate, Eefsting and Hertogh2010). The use of such assistive technologies has generated huge debate around safety, risk, privacy and autonomy (Landau, Reference Landau2009; Niemeijer et al., Reference Niemeijer, Frederiks, Depla, Legemaate, Eefsting and Hertogh2011). Additionally, questions arise such as decision-making around the use of technology (Alwin et al., Reference Alwin, Persson and Krevers2013; White and Montgomery, Reference White and Montgomery2014), establishing consent from the person living with dementia (Martínez-Alcalá et al., Reference Martínez-Alcalá, Pliego-Pastrana, Rosales-Lagarde, Lopez-Noguerola and Molina-Trinidad2016), identification of who gets access to the data (Landau et al., Reference Landau, Auslander, Werner, Shoval and Heinik2010) and incorporating person-centred care into a technology-enriched setting (Robinson et al., Reference Robinson, Hutchings, Corner, Finch, Hughes, Brittain and Bond2007).

Approaches to health care that are based on person-centred principles are increasingly recognised and accepted as a route to the provision of quality care, particularly for people living with dementia. In the UK, this approach has become an integral part of health and social care policy and strategies (Department of Health, 2009; Scottish Government, 2010; Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety, Northern Ireland (DHSSPSNI), 2011a, 2011b; Department of Health, 2015; Welsh Government, 2017).

Theoretical framework for the study

McCormack and McCance (Reference McCormack and McCance2006, Reference McCormack and McCance2010, Reference McCormack and McCance2017a) developed the person-centred practice framework (PCPF) as a holistic structure that focuses on the characteristics of a person-centred culture within which person-centred care can be provided. They define person-centredness as

an approach to practice established through the formation and fostering of healthful relationships between all care providers, service users and others significant to them in their lives. It is underpinned by values of respect for persons, individual right to self-determination, mutual respect and understanding. It is enabled by cultures of empowerment that foster continuous approaches to practice development. (McCormack and McCance, Reference McCormack, McCance, McCormack and McCance2017b: 20)

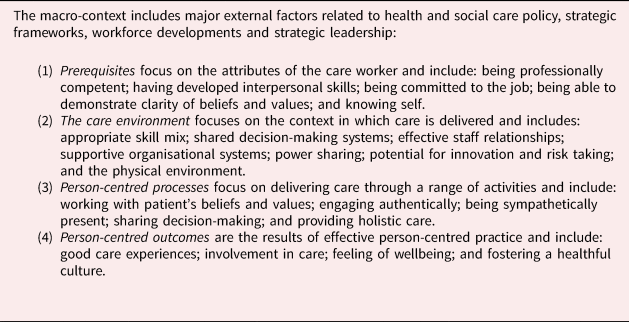

From this viewpoint, McCormack and McCance (Reference McCormack and McCance2010, Reference McCormack and McCance2017a) have operationalised the factors that might enable person-centredness into a macro-context and four constructs: prerequisites, care environment, person-centred processes and person-centred outcomes. All constructs and their full set of attributes are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Person-centred practice framework constructs

Source: McCormack and McCance (Reference McCormack and McCance2017a).

With the widespread consensus that the principles of person-centred care should be at the heart of existing and emerging models of care, we sought to consider how the experiences of people transitioning to supported accommodation related to these principles.

Aim and objective

The aim of this study was to explore the experiences of family carers supporting a relative living with dementia during and after the move to technology-enriched supported accommodation (TESA).

The objectives were to explore:

(1) The ICs’ experience of their caring role and factors influencing the move into TESA.

(2) The ICs’ perceptions of TESA as a care environment and their perceptions of their relatives’ experience of the move and of life in a technology-enriched environment.

This study was part of a larger qualitative investigation about the experience of living in TESA in which the views of people living with dementia as tenants in the facilities, their ICs and paid care staff were sought. Throughout this study, the term ‘supported accommodation’ rather than ‘supported housing’ was used and it is included in the acronym TESA – technology-enriched supported accommodation. The term technology-enriched is used as a descriptor for supported accommodation that has incorporated electronic assistive technology (e.g. sensor-based alarm alerts).

Methods

A qualitative study design with face-to-face interviews supported by a predesigned topic guide was used. Data were analysed using a thematic approach adopting an exploratory method in which an initial list of codes was developed from the themes of the topic guide (Saldaña, Reference Saldaña2016).

Setting and sample

The study was open to inclusion in all five Health and Social Care Trusts (HSCT), where ten TESA facilities were identified within Northern Ireland. One facility declined participation due to organisational restructuring and a second facility did not complete all aspects of data collection. Out of the nine facilities that participated, five of them are located in urban areas, two in large towns and two in medium-sized towns (Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency, 2005). In most cases, the care was provided by a mix of HSCT staff and/or voluntary-sector organisations and management of the facilities is facilitated by housing associations.

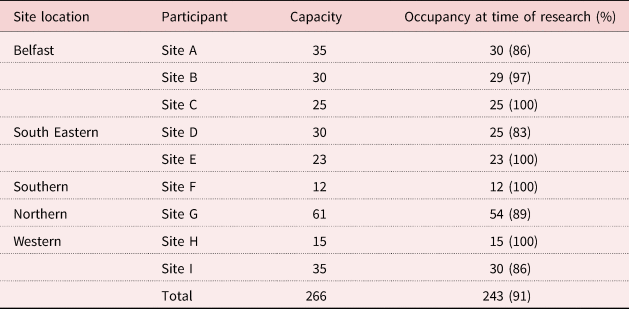

The dwellings consisted of a range of accommodation types including small units for up to 12 people with private en-suite bedrooms and communal living and kitchen areas, bigger units of the same type for up to 60 people and self-contained bungalows or apartments (25 or 30 per facility) within a complex that also offers communal recreational spaces and gardens (Table 2). A purposive sample of all registered next of kin (N = 243) considered to be the IC of the tenants were invited to participate in the study.

Table 2. Number of tenants residing in each facility across five Health and Social Care Trusts

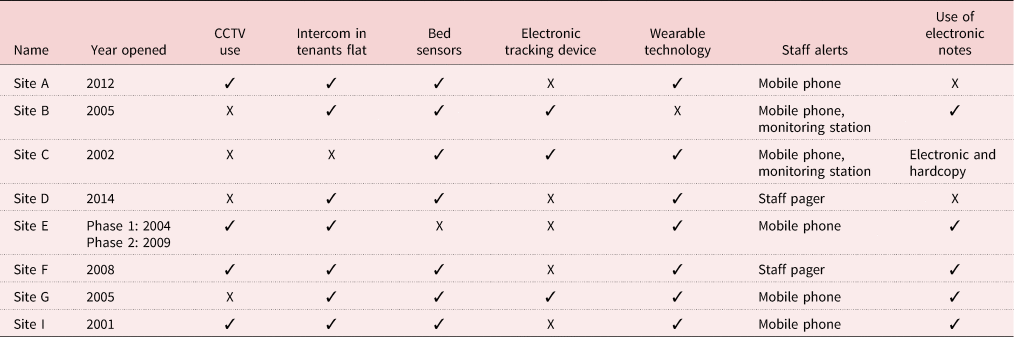

An overview of the technology within the recruited supported accommodation is presented in Table 3. The first facility was opened in 2001 and the most recent was 2014. Since 2001 huge changes in technologies have emerged into the marketplace which have been integrated into the care system. Staff pagers and mobile phones were the most commonly used by paid staff to receive alarms/alert. Additionally, electronic notes were used in all but two housing schemes. Closed-circuit television (CCTV) was used within four housing schemes. All but one site had intercom systems in tenant's rooms to enable two-way communication with staff. Bed sensors, electronic tracking and wearable devices were used in many of the schemes as and when required according to tenants’ needs as opposed to routine use of these devices.

Table 3. An overview of the technology with technology-enriched supported accommodation

Note: CCTV: closed-circuit television.

Recruitment

From December 2015 until the end of February 2016 we sent invitation letters to the managers of the ten above-mentioned facilities. All but one facility agreed to participate. After formalising written consent, the managers were asked to send invitation letters and information packs to the ICs. These packs were provided in prepaid envelopes that contained instructions for the potential participants to contact researchers directly if they were willing to participate in the study. The initial response was low and after follow-up by letter and verbal information by managers in the facilities, 31 responses were received. These responses were unequally distributed across the total number of facilities, therefore, being mindful of bias we aimed to interview at least two participants from each facility but no more than three from a single facility. In total 25 participants took part in the study.

Data collection

Data were collected from February until December 2016 through semi-structured interviews that lasted between 40 minutes to one hour and were digitally recorded. On the day of the interview JR-S, the researcher, formalised consent and reminded the participants about confidentiality and anonymity and the right to terminate the interview at any time or not to answer all the questions. Only one of the 25 participants refused to have the interview recorded but approved to have notes taken. The majority of interviews were undertaken in the supported accommodation facility where their relative resided at a time convenient to the participants – usually before or after visiting their relative. Other venues for the interviews included the participants’ home, the researcher's office or a quiet area in a public venue chosen by the participant. A relatively loose topic guide was used to provide guidance during the conversation while giving participants the opportunity to describe their world richly (Kvale, Reference Kvale2009). The interviews explored what the participants perceived to be their role as an IC and how they felt about it; experiences of any challenges they encountered and why they felt the transition to TESA was necessary; how they perceived the quality of care provided in TESA; and the impact of living in this type of accommodation for both the participants and their relatives.

Data analysis

All interviews were transcribed verbatim by the researcher and also a professional transcriber. After checking the transcripts for discrepancies, data were anonymised, and all identifiers removed. Then, data were uploaded in to NVivo 11, a software package for qualitative data analysis (Bazeley, Reference Bazeley2013). We used a thematic analysis approach as outlined by Braun and Clarke (Reference Braun and Clarke2006) for analysis. This method offers a theoretical freedom which makes it ‘a flexible and useful research tool, which can potentially provide a rich and detailed, yet complex account of data’ (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006: 78). This approach was favoured as it allows the rich overall description of the data when investigating an under-researched area, which is consistent with the exploratory nature of this research.

Furthermore, this approach is compatible with the identification of themes or patterns in an inductive or ‘bottom-up’ way or in a theoretical or deductive ‘top-down’ way (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006: 83). In our analysis, Braun and Clarke's (Reference Braun and Clarke2014) systematic framework for coding all the data was adopted with the resulting codes used to identify themes across the data-set. The first analyst had a key role in the familiarisation with the transcripts and the generation of initial codes and identification of themes which captured ‘something important in relation to the overall research question’ (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006: 82). In keeping with Braun and Clarke's (Reference Braun and Clarke2006) framework, all the interesting data items were coded against all the data extracts that best represented that code. These themes were compared, refined and grouped according to their commonalities and then discussed with the team to ensure the relationships between codes and themes, and themes and sub-themes. The process of analysis, at this point, also involved the constant comparison between transcripts, codes and themes (Glaser and Strauss, Reference Glaser and Strauss1967) to ensure that the structure of the themes was grounded on the data.

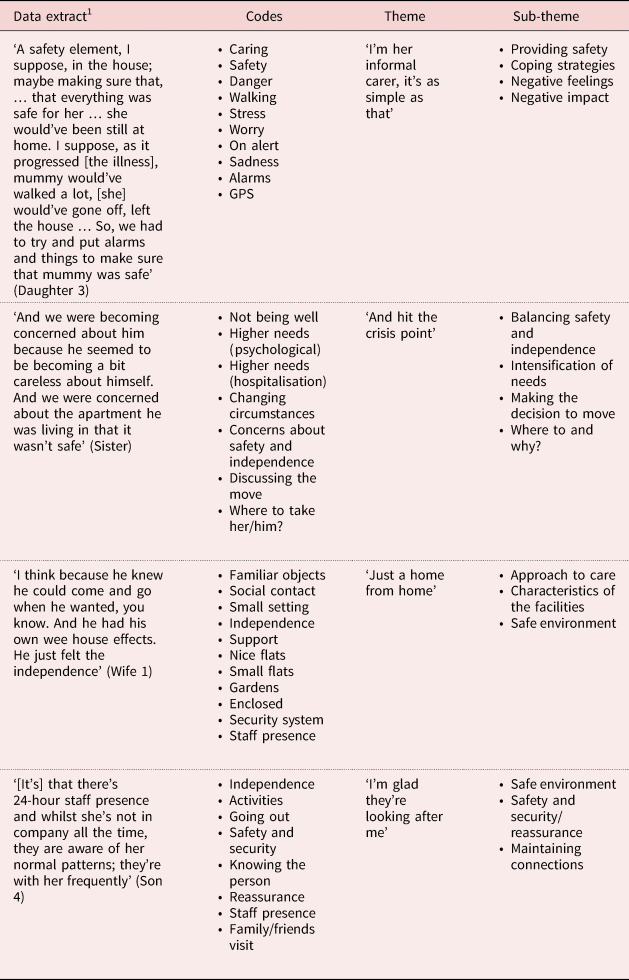

Finally, two of the researchers reviewed the agreed themes and following Braun and Clarke's (Reference Braun and Clarke2006) framework, tested their clarity by outlining a brief description of their meaning and content. The themes were considered in terms of the extent to which they coherently and adequately represented the meaning of the data-set as a whole (Braun and Clarke, Reference Braun and Clarke2006). The detail of this process is shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Sample data extracts with application of codes and final themes and sub-themes

Note: Sample extract that has been coded with one or more of the codes from the adjacent column.

Findings

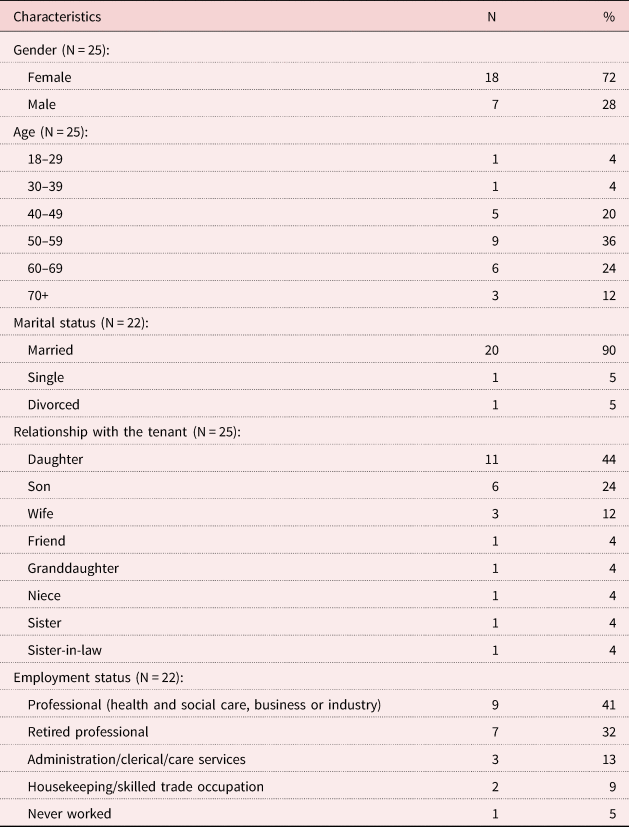

We conducted 25 interviews with 18 females and seven males. The youngest participant was 24 years old and the oldest was over 70. These participants talked about their experience of being an IC for 19 female and five male relatives (two of the participants were siblings who talked about their mother) who have been tenants in TESA for a length of time ranging from four months to 12 years (for full demographics, see Table 5). All except for one participant lived at driving or walking distance from the facilities where their relatives resided.

Table 5. Demographic characteristics of participants

Four main themes were identified in our data. All the themes were named using in vivo codes. The themes of ‘I'm her informal carer, it's as simple as that’ and ‘And it hit the crisis point!’ reveal what was meaningful to the ICs and the factors impacting on their experience. The themes of ‘Just a home from home’ and ‘I'm glad they're looking after me’ describe the life of the people living with dementia in the facilities and those aspects of care in supported accommodation closely associated with person-centred principles. Table 6 provides a summary of themes and sub-themes identified.

Table 6. Four main themes discussed by informal carers (ICs) of people living with dementia and their corresponding sub-themes

Note: TESA: technology-enriched supported accommodation.

Theme 1: ‘I'm her informal carer, it's as simple as that’ (Friend)

For the large majority of participants there appeared to be a natural progression into their caring role as the dementia advanced and the signs of the illness became more apparent, impacting on independent living. The main signs noticed by most ICs were the forgetfulness, the neglect and the increased need to provide more support with practical issues, such as domestic chores, shopping and finances. Some carers, like this son, reported that he saw himself ‘sucked in for more and more caring’ because of the pattern of isolation and dependence developed by his mother who found herself without a purpose in life after the death of her husband for whom she had cared for throughout many years of illness (Parkinson's disease).

Providing safety

Regardless of the circumstances that led participants to the care-giving role, a recurrent topic of conversation was the need to ensure the safety of their relative who may have been living alone in their own independent accommodation or with their wives in the marital home, in the case of married men. ICs appeared to focus their caring efforts on providing safety. Safety was concerned with reducing the risk of harm in the person's immediate living environment and engagement in daily activities, as this daughter described:

The silly things. You know, like putting the milk in the kettle. Forgetting all those things that go along with that. She could've been a danger, maybe, perhaps in her own home. (Daughter 6)

Also, for many ICs the safety issues became more problematic as the illness progressed and other symptoms like wander walking or getting lost were more prominent and it was difficult to keep the person at home. Some participants, like this daughter, resorted to the use of assistive technologies to help:

I suppose, as it progressed [the illness], mummy would've walked a lot, you know, mummy would've gone off, left the house. There would've been, one day, we lived [in town nearby] and mummy would've been found six miles from the house. So, we had to try and put alarms and things to make sure that mummy was safe. (Daughter 3)

Other participants also worried about the possible risk of harm to others as a consequence of their failure to keep their relative safe at home. This son described his experience with his mother:

She'd walked up as far as [the dual carriageway], wandering on the road, side of the road, hadn't a clue where she was and got very tired … She was putting herself at risk and as well as herself, she was putting other people at risk as well, other road users … with all the best intentions in the world, you can try to steer away but you might not be able to and you can just imagine what those people, the driver of that car what would have felt like if he'd hit her and killed her. (Son 6)

Coping

Many of the participants felt they could cope well in their roles and felt supported by statutory services who helped them provide appropriate care. Mainly, social care services helped them navigate the system and provided care packages for their relative which consisted primarily of domiciliary care visitations at different times of the day including bedtime, for some, to deliver meals and administer medication. Participants found this useful for two reasons. First, they felt reassured that their relative was having at least one meal per day as some were worried about a lack of nutrition and, second, participants felt some relief knowing somebody was calling on their relative when they were not available to do so, therefore an alarm could be raised in case of an emergency. This daughter succinctly explains that:

He [the person with dementia] had the carers, not obviously at the very start, but then whenever he started to forget that he'd had lunch and that sort of thing the carer was put on … that was a lot of relief for me … If there's somebody going to the house and getting into the house, I knew he was home, he hadn't wandered in the car, you know, he wasn't lying out the back. It not only was, he was getting food at the proper times, but there's someone checking that he's alive and that's quite something for you to be able to be free. (Daughter 1)

Nonetheless, a small number of participants expressed dissatisfaction with the arrangements of the care packages which due to the lack of empathy from the staff they described as inflexible. A son, in particular, found it challenging when he could not get statutory services to include personal hygiene in his mother's care package. Because this service is not considered a critical need, he could not get a female carer to administer personal care. He found it awkward having to put his mother in the shower and dealing with other intimate personal care, as he explains in this excerpt:

I'm very frustrated because I knew what type of care I was giving mother and able to give mother and when I was looking for help from the social services they couldn't match that same level of care. There were carers coming in to get her out of bed in the morning and give her breakfast. They wouldn't or couldn't do anything for personal hygiene, they said care is based on a critical need basis. (Son 6)

While being in the system was the best mechanism to obtain appropriate services, it was also evident to a few participants that complementary coping strategies were needed. Mainly, these participants found it ‘very hard’ to deal with psychological symptoms and behavioural disturbances characteristic of dementia, such as the repetitive sentences or questions, confusion, agitation, paranoia, lack of motivation and personal hygiene. Given that the participants confronted these challenging situations on a daily basis and, for some, for a number of years, they developed their own coping strategies to deal with them. These included: ‘playing along’, avoiding upsetting topics or using child psychology. For example, this son talks about saving his mother the sadness of grieving for her dead parents once more just by playing along and pretending that they were still alive:

And then she'll talk about her mum and dad: ‘I wonder how my mum and dad are…’ In the beginning I used to say: ‘Your mum and dad died a long, long time ago.’ And then she used to get all upset as if it's just news to her. So, I don't tell her now, I don't correct it … Before, it used to be, it was like a fresh grieving every time; but after half an hour she'll have forgotten about it but she was still getting upset. (Son 6)

A small number of participants appeared to use more practical coping strategies including assistive technologies, such as bed sensors, pendant alarms, CCTV cameras or GPS trackers. Others mentioned using alternative therapies, learning new things or keeping busy: ‘always having a new project’, as one participant put it. Noteworthy, a small number of participants said that learning about dementia was helpful, and, in particular, one participant remarked on an awareness programme provided by her local general practitioner surgery:

The social worker put me in contact with [this doctor] and he ran like a six-week course, right? And anybody who had parents, husbands, whatever, with dementia, went along and every week there was something different: how to take care of them, how to get carers in … It was very helpful. (Daughter 4)

Negative feelings

The great majority of participants were overcome with negative feelings. Generally, they felt guilt, sadness and a ‘sense of failure’. These sentiments lingered throughout their caring career, even after they progressed into the transition into TESA. Being a witness to a parent's functional decline and its terrible consequences was hard for many adult children. As one daughter said, she and her sister ‘found it very hard, it was a feeling that [we] had not done a good job’ (Daughter 10). Another daughter found it nearly unbearable, she said:

It's very sad. It's a horrible disease, it's a horrible thing to … it's hard to watch. It's hard to watch. (Daughter 6)

Again, for adult children it was very hard having to take away power and control from their parents, and this made them feel guilty, as illustrated by this account from a daughter:

And I felt, every time I had to make a decision, I felt that I was taking a wee bit of mummy away, you know. And it was hard. And I don't think anybody really, well my sister didn't realise it, my brother, certainly didn't realise it, that every decision I've made for mummy, even now, even if it comes down to mummy going into a residential home, it's … um … it'll break my heart, you know. (Daughter 2)

Negative impact

In general, it was shown that the caring role was having a negative impact on the participants. For some, life changed in dramatic ways, as this son expressed:

[My life] changed completely. I swapped one profession for another. I retired from gainful employment to really full-time unpaid work. (Son 6)

Similarly, older wives, many of whom had their own health issues, found their care-giving role challenging and felt that they were vulnerable to adverse mental health and wellbeing, and even had to face the criticism of their families. This wife, for example, whose physical ill-health eventually prevented her from being a full-time carer for her husband, ended up feeling guilty and as if she was being judged by family members, she explained that:

I do have a sense of failure that I can't [keep my husband at home] … especially when I hear his own brothers and sisters saying about how easy [my husband] is to manage. But I couldn't, I had to get treatment … Well, I'm feeling much better now a year on. I still get very tired and I still realistically know that I probably couldn't take him on 24/7 again. (Wife 3)

Other prevalent negative impacts amongst the majority of participants were the constant worry and pressure they were experiencing, to the point that over time the caring responsibilities became too demanding. For some, time issues and geographical distance added extra pressures and worries to their roles. As explained here:

Well, um, it was becoming increasingly difficult because, um … my mother had developed a pattern … where in the evening she would become quite disorientated … And she would've phoned me repeatedly maybe ten times in an hour, and it was difficult from such a long distance away to settle her … So, if I could find the right thing to say to get her settled, you know, and get her to go to bed, I knew that the next morning she would be fine. (Son 4)

Also evident amongst many of the participants were the difficulties in balancing care-giving with other family demands, at the risk of neglecting their own families, as illustrated in this quote:

But the family are saying ‘it's not my job, it's not my duty’ to be looking after him; I should be putting more time into them, into my grandchildren. (Daughter 1)

Theme 2: ‘And it hit the crisis point!’ (Daughter 3)

Over time, care-giving prior to moving into TESA posed different challenges to the participants. While the majority of them were fully committed to their caring role and assumed their responsibilities unconditionally, external factors related to the physical environment (people living in their homes), the progression of the illness (higher needs) and their limited physical presence, highlighted issues of safety and risk that eventually led to a crisis point and the realisation that care-giving was difficult to maintain under such circumstances.

Balancing safety and independence

Numerous accounts illustrate the difficulties encountered by the participants who tried to balance the need for independence of their relative and their safety. The wander walking, getting lost, having to be out in the streets or country lanes looking for a relative or having to report them to the police or to have them returned home by the police were common experiences for the majority of the sample, which added more stress to their role and led, in many cases, to take extreme measures, such as preventing the driving or ending walking routines, as this participant explains:

And there were a couple of incidents where people brought him back because he'd crossed the road without looking or, you know, not going near the lights, just heading out on the road. And once the police brought him back, he crossed the bridge, and once that's happened I said: ‘Right, that's the walking finished.’ (Wife 3)

Moreover, a few participants were confronted with moral and ethical dilemmas about the methods they employed to avoid wander walking, which consisted mainly of locking their relatives up in their own homes:

I couldn't keep him in the house at that point and what I was actually doing was … I put him in bed in his own house, lock up and make sure he was absolutely sound and be back in the morning for him to wake him up. And that's not good. (Daughter 1)

Many participants expressed their concerns that the functional decline as the illness progressed put relatives at risk of falls or harm to themselves or others:

But, you know, she could have fallen down stairs and nobody would know from the 6 o'clock visit in the evening to the 10 o'clock visit in the morning by the carers. So, that's six, ten, 16 hours she could've fallen just after that, and 16 hours she is lying where she is lying. So, you know, the safety thing. (Daughter 9)

Some of the participants considered the possibility of caring for their relatives indefinitely, but as their needs intensified, they realised that it was time for change as they felt they were incapable of providing appropriate care. This was particularly difficult for some participants who also experienced their own physical decline, as told by this wife:

And then, I have arthritis which I've had for years, before I retired I had arthritis, … and he became incontinent. And it was terrible. I couldn't manage at all. He wouldn't let me near him, he didn't really know me. Um, and it was really, I ended up … and I was exhausted, as well. I realised then I needed the recovery time, I was very, very tired. (Wife 3)

For many, the pressures of care-giving were increasing significantly as the emotional and psychological needs of their relatives increased. As a result, participants not only felt upset by their relatives disturbing behaviours, but also realised that further intervention was imminent. This is illustrated in the accounts of this daughter:

Well, … then, um, I suppose it's like a lot of things; change came when there was crisis, agh!! … She started to get paranoid about different people coming into the house, that they were stealing off her and things like that. So, basically that was one of the reasons why she couldn't stay on her own … We decided that we would try and leave my mum for a few nights. I'd be staying the odd night with her and then she was phoning me constantly; she was forgetting that she had phoned me. It was very disruptive to my home life and to my brothers’ as well. (Daughter 5)

Making the decision to move

Once the events that prompted the decision to move the relative to more appropriate accommodation have unfolded, on some occasions this decision was made jointly:

Obviously, he [relative living with dementia] came to see the place before we made the decision, before he made the decision. (Sister)

It was not unfamiliar to see how health or social care professionals played a part in making the decision for the transition given that they had supported the participants during their moments of crisis. As this daughter explains:

The crisis point was then, about whenever erm, after [my children] were born and then my sister had her children and then we were at the house one day and mummy just became, … very unwell, so, then, mummy was admitted to hospital. Um, so that basically was the crisis. And then mummy was in hospital [for a few months]. And then round that time, there were various meetings, and, I suppose, they knew what her circumstances were; it was only the two of us, and we had young families and we were working, we'd jobs and they were sort of saying: ‘You know, the reality is, you're not going to be able to do this.’ I suppose, we were starting to realise that ourselves. (Daughter 3)

Where to go and why?

While it appeared that for the majority of the sample safety was a key factor in the transition, ICs also valued the independence and autonomy that a new living environment could offer, therefore, they were careful in choosing facilities that met those conditions, as explained here:

We just came and had a look here [the facility] and thought it was fabulous. Because we wanted him to be independent for as long as he can be independent. We just thought that that was a step too far to be going into a residential-type home environment and we knew he would hate it! (Sister-in-law)

While some ICs get to know about the TESA for people with dementia by word of mouth, in many other cases the decision to move their relative into this type of supported accommodation is facilitated by the advice and information received through statutory services, as this daughter explained:

I was talking to a hospital social worker who was an absolute gem, she was lovely, so she was. And after a while she came and she said: ‘[XXX] I think [this facility] might be the best place for your mother.’ (Daughter 8)

In the majority of cases one of the key enablers of the transition, was the facility ethos. For many participants, managers and staff demonstrated the right attitude and it was evident to many more that the approach to care in the facilities was based on the principles of the promotion of life skills, relations and interactions:

I remember them asking him why he wanted to move into his own place. Obviously he is asked a lot of questions before moving from the [nursing home], you know, ‘Did he want this, and that…’ The manager from here went to [the nursing home] and talked to him and she was able to tell me that he said that he didn't want to be in an institution. (Daughter 1)

And she says:

Whenever he can say that to you, he's not ready, you know? He needs another chance to be his own person in his own place. He still has too much ability and his own thought. (Daughter 1)

It also appeared important to the participants that the staff in the facilities demonstrated having the appropriate repertoire of skills that could facilitate the transition and life in the facility:

But, I mean, it's very reassuring to me, that she's in a place where staff are well trained, recognise the condition, recognise, become familiar with each resident. (Son 4)

More importantly, numerous participants described how the facilities offered the safety and minimisation of risk that for many led to the decision to move. In the facilities their relatives were safe: from harm, wander walking and getting lost; some of their big fears. The fact that there was a 24-hour presence of staff was also reassuring:

I think it's a great relief for us to know that the staff are there all the time and they would pick up on things. (Niece)

A minority of participants stated that assistive technology was not a factor that influenced the transition of their relative to TESA, in opposition to a few that mentioned this as a decisive factor. However, in general, participants reported they were not aware of the use of assistive technologies to support care for people living with dementia:

Well, um, I … I don't see anything in assistive technologies here other than is a basic prerequisite of health and safety. (Son 2)

Whether the participants were aware of the use of assistive technologies in the facilities or not, it became apparent during the interviews that the main advantage afforded to the technologies used was the safety it provided. As the people living with dementia engaged with life in the facility, participants were able to describe how the various assistive technologies used in the facility appeared to have the purpose of keeping the person safe, and this, unanimously, was very reassuring, as this son explained:

I didn't know about what kind of technological support or systems they [the facilities] would've had. I was looking for somewhere where she would be safe, so the important thing for me was that there was staff, trained support staff. However, when we saw this and learned that there were these, that this technology was there, I found that quite a reassuring thing. (Son 4)

In general, the physical environment was found to be suitable and appropriate to the specific needs of the tenants. It offered gardens, spacious rooms and other features that made the dwellings and apartments comfortable and enjoyable:

…the apartments are well spaced out, they are not cramped and there are good grounds outside … It's within a housing estate … It's just like a wee oasis in the middle of it all. (Daughter 6)

Theme 3: ‘Just a home from home’ (Sister)

In general, the positive aspects of the supported accommodation model outweighed the very few barriers noted by the participants. For the majority, care in the facilities was provided in a holistic manner with the right level of engagement and participation of the tenants and the ICs. For many, the transition was described as ‘smooth’, and as the title of this theme suggested it appeared to be ‘just a home from home’ move. The factors that made this possible are presented in the following sub-themes.

Approach to care

The supported accommodation model in small settings was found to be the preferred and most adequate model of care for people living with dementia. Some of the advantages of this model according to participants included small settings where people could thrive and be buffered against social isolation; settings where people's individual needs were catered for and not restricted to a one-size-fits-all system. This is eloquently described by one participant who said:

I don't think there could be a business formula with dementia … [To] care successfully for people that are suffering from dementia requires a slightly different cost approach from the containment that you have in a nursing home facility where people are confined in rooms or beds and there's a ratio of one to ten or one to 15. Here you've got maybe somebody that is in need to go downtown to get to do a message and that stimulus is very important to them and that opportunity for them to get out and engage with the community and have that independence. It's something that should be encouraged and patients, for want of a better description, thrive on that and we all want to encourage that. (Son 2)

Characteristics of the facilities

Independence, decision-making and choice featured as some of the most relevant characteristics of the approach to care offered in the facilities:

They make them do things for themselves to see how much help they would need to do them. Because, now, in the morning it would take my mother, aww, I don't know, hours to get ready in the morning to get dressed and all, you know. But they say they won't take that away from her because that's still her independence. (Daughter 8)

Positive staff attitude working together with tenants and ICs promoting and encouraging effective communication and relationships appeared to be other features in the facility highly valued by the overall majority of participants:

…they all [the staff] seem not just to have what obviously people doing that job would have to have, and that is the sort of empathy and compassion that you need, and patience. (Son 4)

The safe environment provided not only by the design features of some of the facilities, but also through the use of the assistive technology and the presence of staff, was particularly commended by the participants; for example:

As soon as she goes to bed her sensor's on … She might've just sat on the bed, she might've tried to get down to the toilet, she might've fallen; they're there. And for me that's just such a safety net. (Granddaughter)

A small number of participants reported on negative aspects of the delivery of care. Mainly, they were concerned with the lack of facilities for smokers, shortages of staff, and some lack of provision of activities and one-to-one:

I know there are times where they're short staffed and they don't have the time, really, and stuff like that. I think there have been problems when they don't have the full squad in. (Sister-in-law)

As I said, I think definitely there needs to be more one-to-one … So, that's why I think, that she probably does get restless, ’cause she's just sitting there and she's nothing to do. But I've noticed that there isn't a whole lot goes on at the moment. (Daughter 2)

The youngest participant, one granddaughter, reported on the lack of internet connection in the facilities which limited the means of communication between tenants and family members who could not visit regularly.

Theme 4: I can't imagine why I wouldn't recommend this place to anybody (Granddaughter)

This theme focused on the advantages or disadvantages the participants mentioned about life in the facility for their relative. Their discussions focused mainly on the improvement of the quality of life of their relatives since their transition into the facility. Many of the participants also talked about the implicit gains or disadvantages for themselves as a result of the move.

Satisfaction with care

Overall, there was a sense of satisfaction with the care offered in the facilities with many participants commenting that they would recommend them to anyone:

I can't imagine why I wouldn't recommend this place to anybody ’cause for me, as I say, granny wouldn't be living if she wasn't in here; in my opinion and my family's opinion. (Granddaughter)

Other examples of satisfaction with care were associated with the apparent feelings of wellbeing, happiness and contentment shown by their relatives:

Oh, it's very reassuring. You know, because, the number one priority, I'm sure, for every carer is that the person, that you know that they are, as far as possible, content. And she is a great deal more content, than she was in her own home, especially during those times when she didn't know where she was. (Son 4)

Equally, the social aspect of the facility in terms of activities and encouragement of social life (outside and within the facility) and relationships was also praised by the participants:

But then she's made friends here, too. Which is good, because if she was at home she wouldn't have any of that. (Daughter 8)

…she loves going to her day centre and she loves living where she's living. And she's just a different person now. (Daughter 7)

Again, the transition to live in supported accommodation has also offered the advantages of safety and security for the tenants and ‘peace of mind’ for the participants. The 24-hour staff presence is reassuring for the participants who felt more relaxed and under less pressure:

Benefits in my life?!! There's’ benefits in my life because I don't worry much! I'm not as much concerned. I'm not getting the phone calls in the middle of the night because she's pulling the cords. So, it's made my life better because it has taken a lot of pressure off me. (Son 1)

And I find the staff are very good at, umm, they know her very well. It gives me such a peace of mind to get to put my head on the pillow at night and know that she's happy. I sleep in peace and I can lift the phone at any time of the day or night and phone her and it's never seen as a bother. (Daughter 5)

Maintaining connections

Finally, living in the facility has provided both parties with the opportunity to keep family connections while the people living with dementia enjoy life to the best of their abilities:

I, definitely, am looking after her as much as I can from the 500-mile difference, yes, distance … And, um, they [the facility] are very happy that I'm coming over every month, and I could not do that even now she is in somewhere that I know she is comfortable. I can't live with the thought that I'm not visiting. (Daughter 9)

Discussion

In this study, the accounts of ICs about their experiences of caring for a relative living with dementia who, eventually, moved into TESA are captured. It is interesting to note that ICs assumed this caring role in line with Archbold's (Reference Archbold1983) conceptualisation of care-giving into roles of either providers or managers as the dementia progressed prior to transition. As care providers, ICs identified the needs and performed the tasks necessary to fulfil them. This care provider role was dynamically evolving, through provider and manager, into a single care manager modality, which was considered to continue post-transition. This is aligned to the emerging understanding of the complexity consistent within the caring role (Ryan and McKenna, Reference Ryan and McKenna2015; São José, Reference São José2018). This change in the care-giving role was a natural transition that emerged from the need to support their loved one move into TESA and emerged from the ‘hitting the crisis point’ theme where ICs identified the provision of safety as a key issue. For example, in line with other reported research (Brittain et al., Reference Brittain, Degnen, Gibson, Dickinson and Robinson2017; MacAndrew et al., Reference MacAndrew, Brooks and Beattie2018), ICs’ responses to wander walking were particularly stressful, with some ICs feeling morally conflicted by the methods required to avoid risks that emerged by wander walking. This is an important finding for two reasons. Firstly, safety appeared to be one of the main factors associated with stress and the decision to move the person living with dementia into supported accommodation; and secondly, it is an important component within the provision of TESA which offers a safe environment, 24-hour staff presence and assistive technologies.

When transition was described as ‘just a home from home’, ICs acknowledged that the safe physical environment enriched with smart home technologies provided the reassurance and the ‘peace of mind’ they needed to feel that their relative was being looked after well and that the new accommodation felt like being at home. The finding that the decision to move their relative from home was delayed in all cases until the ultimate crisis point was reached resonates with other research on family care-giving and entry to care (Nolan and Dellasega, Reference Nolan and Dellasega2000; Carter et al., Reference Carter, McLaughlin, Kernohan, Hudson, Clarke, Froggatt, Passmore and Brazil2018) and is important in considering how services in the community pick up such scenarios and the preparedness required in supported accommodation to support transition during crisis. ICs report that when the caring responsibilities ‘hit the crisis point’, they feel compelled to identify the most appropriate services provided by others, especially statutory services which had supported the crisis(es).

The need to provide safety is a priority, with the desire to ensure physical and emotional comfort, shifting their role to focus on ‘monitoring other care-givers to be sure this work was done properly’ (Caron and Bowers, Reference Caron and Bowers2003: 1261). Carter et al. (Reference Carter, McLaughlin, Kernohan, Hudson, Clarke, Froggatt, Passmore and Brazil2018) highlight that entry into a nursing home does not necessarily mean the end of the care-giving and decision-making relative but rather a new phase of their care-giving trajectory. Within the TESA facilities and model of care, where family input is encouraged, this may mean care-giving does not necessarily lessen.

One important aspect of our findings is that the move to TESA was not influenced by the added value of pervasive technologies in the facilities. Only a few participants mentioned that this is a decisive factor; generally, they were not aware of these technologies for supporting care for people living with dementia residing in supported accommodation. This is an important finding in our study which adds new knowledge in the area. While technologies appeared important to the ICs in terms of provision of safety, the characteristics of the facilities most valued were those directly linked to the caring ethos prevalent in the facilities.

The focus on the caring ethos of the facilities by ICs raises important issues about the prominence of the person-centred caring culture within a space that utilises and integrates technology to inform care. Exploring the findings aligned to the PCPF, the constructs of the care environment, person-centred processes and outcomes (McCormack and McCance, Reference McCormack and McCance2017a) are the prominent elements that emerge. In the themes of ‘Just a home from home’ and ‘I'm glad they're looking after’ me, there were numerous accounts of how focused the facilities are on the provision of holistic care. ‘A home from home’ transition meant that both ICs and their relative participated in decisions regarding all aspects of care, giving their relatives control over how they wanted their home to be furnished and decorated, as well as planning their care and activities within and outside the facilities according to their own choices.

These exchanges not only reflected the desire for a cultivation of effective communication and relationships in the facilities as outlined in the person-centred processes of the PCPF, but are also in line with National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines on the transition of older adults from different settings which emphasise the principles of person-centred care and information sharing as overarching principles of care and support during transition (NICE, 2015). ICs referred to how the positive attitude of the staff, their awareness and knowledge of the ‘normal patterns’ of the people living with dementia and the things that were important to them helped to create an environment in which they felt encouraged, motivated and valued, demonstrating how a sympathetic presence as defined in the PCPF (McCormack and McCance, Reference McCormack and McCance2017a) may be more important than the physical presence. Likewise, they commended the dedication of the staff at all levels who were instrumental in delivering interventions that took into account the full set of psycho-social needs of each individual tenant in the facilities. All these elements are also suggested by McCormack and McCance (Reference McCormack and McCance2017a) to be markers of effective person-centred practice.

Safety was a key finding both in the transition into the supported accommodation and the reason ICs were satisfied with the technology-enriched environments. The accommodation within this study provided unique technologies to support tenants that are not available in standard supported-living environments. For example, all but one scheme offered wearable devices (bracelet or pendant) to tenants, after a needs assessment, which provided ICs and tenants with a sense of security. In line with previous research (White and Montgomery, Reference White and Montgomery2014), this type of technology gives tenants the freedom and independence to participate freely in wander walking within the accommodation but for ICs to be content they can immediately get assistance if required, providing the IC with peace of mind (Alwin et al., Reference Alwin, Persson and Krevers2013; Mao et al., Reference Mao, Chang, Yao, Chen and Huang2015). Therefore, within a technology-enriched setting a safe environment can be provided to enable wander walking. Dewing (Reference Dewing2011) identifies that wandering is often present for people living with dementia; the mechanism behind this is fully understood and yet the need to enable rather than dismiss (because of associated risks) is important. Equally, if the tenant wakes up and leaves their bed, the bed sensor will alert staff to the tenant leaving their bed and staff are able to check on the tenant, particularly if they are prone to become disorientated. Once again, all but one scheme was able to speak to the tenant through an intercom in their living space, so they had immediate contact with staff in the event of urgent assistance. When a person expresses an interest in transitioning into TESA, part of the transition protocol is to give information on the technologies in place and seek consent to use it. This is part of establishing the tenure agreement.

The participants demonstrated how the supported accommodation model in small to medium-sized settings is an acceptable model to support people living with dementia and their families. The main characteristics of this model that appeal the most consist of the use of non-intrusive ubiquitous assistive technologies which provide security and safety, and most of all the approach to care which is underpinned by the principles of the PCPF. This paper adds an in-depth perspective of strategies to ensure that people living with dementia enjoy an independent life for longer in the community when the appropriate support from family, carers and statutory services is made available and when such support is based on a practice framework designed to enable a holistic approach to care. Services, in particular, may benefit from this type of research that highlights the need to consider health and social care from a whole-systems perspective, which advocates treatment in community settings (Bengoa et al., Reference Bengoa, Stout, Scott, McAlinden and Taylor2016). Dementia care based on these principles would avoid reactive solutions when things ‘hit the crisis point’ that may lead to unnecessary hospitalisations and/or institutionalisation. Equally, ICs may be guarded from the adverse effects of care-giving responsibilities and could be provided with appropriate and timely information that would help them, as well as the people living with dementia, to make informed decisions about care provision. This would enable the people living with dementia to live independently for longer in the community where they could thrive and flourish, and maintain meaningful relationships with people and places.

Conclusion

A review of the literature identifies a lack of research on and indeed availability of viable supported accommodation options for people living with an established dementia. This paper describes research, as part of a larger study, completed on the experience of ICs of people living with dementia and the impact of caring as well as the transition into TESA. The findings provide an understanding of the care-giving responsibilities and how ICs evolve from a care provider modality role to a care manager one where the services sought to provide the necessary care in the context of person-centred principles. These findings are relevant from a health and social care point of view which emphasises the need to provide appropriate services based on a whole-systems approach to care.

Financial support

This work was supported by the Health and Social Care (HSC) Research & Development Division of the Public Health Agency in Northern Ireland (Reference COM/4955/14) in conjunction with the Atlantic Philanthropies, an international grant-awarding body. The project is part of the HSC research strand into the ‘Care of People with Dementia in Northern Ireland’. None of the awarding bodies have participated in any of the activities related to the research.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical standards

This study was given a favourable ethical opinion by the Ulster University Ethics Governance Committee study (Reference 15/0073), then the Research Office of Ethics Committees of Northern Ireland (ORECNI) on 28 August 2015 under REC Reference 15/NI/0160, and following that Health and Social Care Trusts relevant to site location.